Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Rzepka Conspirators

Uploaded by

api-2353720250 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

168 views13 pagesOriginal Title

rzepka conspirators

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

168 views13 pagesRzepka Conspirators

Uploaded by

api-235372025Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

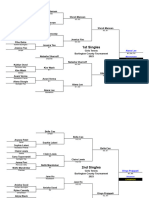

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 13

AHB 23 (2009) 19-31

CONSPIRATORS COMPANIONS - BODYGUARDS:

A NOTE ON THE SO-CALLED MERCENARIES SOURCE AND THE

CONSPIRACY OF BESSUS (CURT. 5.8.111)

*

Jacek Rzepka

It seems obvious to the author that there are interesting parallels between Curtius

narrative of the conspiracy of Bessus against Darius, and especially of Patrons role in

this affair, and the Philotas affair, the most famous conspiracy, and subsequent political

trial, which took place during Alexanders expedition. In the former conspiracy Darius

did not believe the informer who revealed the conspiracy among his staff, and, as a

consequence, he lost his life. In the latter case Philotas did not inform the king about a

conspiracy he had heard of, and Alexander only escaped danger thanks to knowledge

about it which he received from another informer. The failure of Philotas to inform the

king of the plot may partly be explained by his fathers previous false warning of a plot

by Philip the Acarnanian to poison Alexander. These parallels have so far been rather

overlooked in Alexander scholarship, and the purpose of this article is to examine them.

These resemblances furthermore re-open the question of which sources were available to

Curtius, when reporting the last weeks of Darius III, and it is to this question we first

turn.

Quintus Curtius Rufus narrative of the last weeks of Darius III is believed to be

untrustworthy in many respects. Some of the events leading to Bessus coup dtat are

held to be no more than literary fiction. For example the meeting of the Persian

commanders at Ecbatana is considered to be one of the least plausible episodes. Modern

commentator, however, make a favorable exception for the role of Patron the Phocian

1

,

a mercenary commander who revealed the conspiracy of Bessus and Nabarzanes to

Darius, and who is sometimes supposed to be one of the authors responsible for the

picture of Alexanders campaign we get from the Persian camp, one of the persons

behind the so-called mercenaries source. It would be only reasonable to assume that

Patron the Phocian plays a key role in Curtius account because his report formed the

key source utilized by that author.

The existence of a mercenaries source was once suggested by Julius KAERST

2

; but the

theory was expanded by William Woodthorpe TARN, who made the mercenaries source

* All three-figure dates in this paper are B.C., unless otherwise indicated. Translations of Greek and

Latin authors are usually LCL ones. However, there was, as often, a need to standardise termini technici

variously rendered by the original translators.

1

How little can be said on Patron is manifest in T. Lenschau, RE 18 (1949) 2291, s.v. Patron 5.

2

Julius Kaerst, Geschichte des Hellenismus vol. I

3

, Leipzig 1927, 544: Und dann drfen wir, einer

Vermutung von Ranke folgend, noch einem besonderem Grund fr diese Griechenfreundlichkeit daraus

herleiten, da die Quelle Diodors Informationen aus dem Lager der hellenischen Sldner, die fr Dareios

gekmpft htten, erhalten haben wird. Cf. L. von Ranke, Universal History vol. 1: The Oldest Historical

Group of Nations and the Greeks, New York 1885, 422.

Jacek Rzepka

Page 20

the only account of Alexanders campaigns as seen from the Persian side. TARN believed

that the mercenaries source was not utilized by the majority of Alexanders historians, but

was exploited by both Diodorus and Curtius

3

. Under the influence of TARNs book the

existence of the mercenaries source gained for a while the status of the scholarly communis

opinio. The first and most definite refutation of the mercenaries source came from the pen

of Lionel PEARSON who denied its existence

4

. PEARSON criticized TARN for taking the

silence of some of the sources (Arrian and Plutarch notably) as proof that they had no

access to a source reflecting the feelings and the actions of Greek mercenaries in Persian

service, and accused him of an attempt to build up the character of this unknown

author whose object is to tell the story of mercenaries, as well as of selective use of a

number of isolated details from Diodorus (p. 80). Equally disparaging was the criticism

of Peter BRUNT that the imaginary mercenaries source need not have been the only

version of Alexanders war accessible to the ancient historians of Alexander from the

Persian side, and that some of the information alleged to come from the mercernaries

source, such as the details of the Persian array at Gaugamela, could have been generally

known. He also argued that access to the mercenaries source was not restricted to the

followers of Clitarchus

5

. BRUNT finally suggested that the account of Darius end could

have been inspired by oral communication from loyal Persians or from mercenaries (p.

153). Yet he stopped his discussion of TARNs theory short of the romantic stories of

Darius last days, which he held to have been invented by Curtius.

A conciliatory approach was proposed by Rotraut WOLF who argued that it was

Cleitarchus who had transmitted to later Alexanders historians the oral tradition of

Darius Greek mercenaries

6

. WOLFs conclusions are followed with some reserve by

John ATKINSON

7

. This leading expert on Curtius, specifically referring to his account of

the conspiracy of Bessus, stresses that on the conspiracy against Darius the ultimate

source could just as well have been Persians who abandoned Bessus and surrendered to

Alexander: they had good reason to distance themselves from the actions of Bessus and

Nabarzanes

8

. Another Curtius specialist, Elizabeth BAYNHAM, reduced the

3

W. W. Tarn, Alexander the Great vol. 2, Cambridge 1948, 71-75 and 105-6.

4

L. Pearson, The Lost Histories of Alexander the Great, New York 1960, 78-82.

5

P.A. Brunt, Persian Accounts of Alexanders Campaigns, CQ NS 12 (1962) 141-55.

6

R. Wolf, Die Soldatenerzhlungen des Kleitarch bei Quintus Curtius Rufus (Diss. Wien 1963). The results of

Wolf were wholly accepted by her Doktorvater F. Schachermeyr, Alexander der Grosse. Das Problem seiner

Persnlichkeit und seines Wirkens (Sitz. Wien 285) Wien 1973, 196, n. 214. P. Goukowsky, Diodore de Sicile:

Bibliothque historique Livre XVII, Paris 1976, xxvi-xxviii, follows Wolf. He adds his own explanation of

how the Soldatenerzhlungen of both sides reached young Cleitarchus studying at Athens.

7

J. Atkinson, Q. Curtius Rufus Historiae Alexandri Magni, ANRW 34.4 (1997), 3447-83, at 3462.

Actually, Atkinson has suggested briefly some conciliatory ideas which are now referred to Wolfs book

already in 1963 (Primary Sources and the Alexandereich, AC 6 (1963), 125-37, at 133-4).

8

J. E. Atkinson, A Commentary on Q. Curtius Rufus Historiae Alexandri Magni. Books 5 to 7.2,

Conspirators Companions - Bodyguards

Page 21

conversation between Darius, Patron and the Persian council as reported by Curtius

(5.8.6-9) to the level of a philosophical digression

9

.

However, there are other scholars who continue to admit that there could have been a

mercenaries source, and others who indeed insist on its existence. It has been suggested,

furthermore, that Patron the Phocian himself may have either supplied a verbal account

of the Bessus Conspiracy, which was subsequently recorded by the mercenaries source, or

may himself have left a literary account, which constitutes wholly or in part the

mercenaries source

10

. Even so, the theory of a mercenaries source still has no general

acceptance

11

.

The modern reader cannot fail to be surprised by the vast amount of space that

Curtius devotes to Patrons warning and to Darius refusal to take action against Bessus

and Nabarzanes. BAYNHAMs proposal to reduce this episode to a philosophical

controversy introduced by Curtius himself may be attractive, but it is not the only

possible explanation. Why then, one should ask, did Curtius write so much about

Patron? The latter is a person otherwise practically unknown

12

. Why was he elevated by

Amsterdam 1994, 134, cf.: the studies quoted in the previous note.

9 E. J. Baynham, Alexander the Great: The Unique History of Quintus Curtius, Ann Arbor 1998, 112-3; cf.

also J.E. Atkinson, Originality and its Limits in the Alexander Sources of the Early Empire, in: A. B.

Bosworth and E.J. Baynham (eds.), Alexander the Great in Fact and Fiction, Oxford 2000, 307-26, at 319-26,

with an argument for novel elements in Curtius accounts of conspiracies at the Macedonian court.

10 To my knowledge it was N.V. Sekunda, The Persian Army 560-330 BC, Oxford 1992, 30, who first

suggested, briefly, but firmly, that Patron was one of the authors behind the mercenaries source. E.

Badian (Darius III, HSCP 100 (2000), 241-67 at 262-3) thinks that the account of the Bessus conspiracy

may be based on the report by Patron, and (in Conspiracies, in: A. B. Bosworth and E.J. Baynham

(eds.), Alexander the Great in Fact and Fiction, Oxford 2000, 50-95, at 86-7) states that These and similar

items are obviously Curtiuss own, decorating the basic account from Patron and that Our information

comes mainly, as has often been conjectured, from the Greek mercenaries and their leader Patron leaving

it unclear whether he considers Patron to be a literary or oral source. He furthermore raises some doubts

as to the credibility of his account (Conspiracies, 86, n. 70: He and his mercenaries would not only

have had no idea of what Persian nobles had been discussing among themselves, but would have had to

find an explanation for their final desertion of Darius and the lateness of their surrender). See also O.

Battistini, Sources de lhistoire dAlexandre le Grand, in : O. Battistini & P. Chauvet, Alexandre le

Grande : Histoire et dictionnaire, Paris 2004, 968-971, at 968 (with some hesitation).

11 Scholars who do not explain away doubts about the veracity of Curtius Rufus account by literary

conventions followed and its philosophical content still try to demolish the mercenaries source theory on

factual grounds. Thus P. Briant, Darius dans lombre dAlexandre, Paris 2003, 192-3 starts his argument from

the standpoint that Darius is said to have been unable to understand any language but Persian, he

therefore denies the truthfulness of the account (197-8), and finally concludes that the mercenaries source

nest rien dautre quun fantme.

12 The identity of Patron and the Paron of the manuscripts in Arr. 3, 16, 1 has to be accepted, but little

more can be added; cf.: A. Schaefer, Demosthenes und seine Zeit vol. 32, Leipzig 1887, 173; cf. Lenschau,

RE 18 (1949) 2291; H. Berve, Alexanderreich auf prosopographischer Grundlage (Mnchen 1926):

Prosopographie no. 612.

Jacek Rzepka

Page 22

Curtius (or his source) to play the role of a wise, though repeatedly ignored, warner

13

? Is

this really mere convention? A sophisticated play with motives? Or, maybe, someone

had an interest in inserting the Patron episode into the story?

The best-known example of Curtius unequal treatment of the events of

Alexanders reign is, of course, the amount of space he devotes to the Philotas affair. It is

especially instructive for our understanding of Curtius historical methods, since we can

compare his treatment of the event with ways in which the other Alexanders historians

presented the end of Philotas

14

. In Curtius the Philotas affair

15

is the central event of

Alexanders clashes with his generals in Curtius (6.7-11.40 and 7.1.1-5), whereas the

other ancient historians of Alexander tend to focus on the Cleitus affair.

The deaths of Philotas and his father and the end of Cleitus at the hands of Alexander

to this day provide the basis for any negative assessment of Alexanders reign. All

scholars preoccupied with diminishing the greatness of Alexander invariably go back to

Curtius description of the end of Philotas

16

. No ancient historian of Alexander conceals

that Philotas was not guilty of having taken part of the Dimnus conspiracy, and that his

actual crime was to have failed to defend the king properly by not revealing the

conspiracy to the monarch immediately. In these circumstances we can be certain that

Alexander and his friends were well aware of the danger which the elimination of

Philotas meant for the royal image (even if the intrigues leading to the death of Philotas

were not coldly planned several months before his trial).

13 Such a role would have been well known to the readers of Herodotus, whose influence on Curtius

(without the intervention of Cleitarchus) is now acknowledged, see J. Blnsdorf, Herodot bei Curtius

Rufus, Hermes 99 (1971), 11-24; W. Heckel, One more Herodotus reminiscence in Curtius Rufus,

Hermes 107 (1979), 122-3. Curtius imitatio Herodoti includes the way he presents the Persian army in 3, 2,

2-3; the ill-omened visions that threatened Darius (3, 3, 2-7); but also, most importantly, the counsel given

by Charidemus of Oreus, a naturalized Athenian, as an exile in Persian service to Darius (3, 2, 10-19) a

role which parallels that of the exiled Spartan king Demaratus in Herodotus. For the Charidemus episode

cf.: E. Baynham, Alexander the Great: The Unique History of Quintus Curtius, 136-40.

14 A striking statistic can be found in E. Kapetanopoulos, Alexanders Patrius Sermo in the Philotas

Affair, AncW 30/2 (1999), 117-28, 117-8 (619 LCL lines in Curtius against 32 lines in Arrian and 86 in

Plutarch); cf.: A.B. Bosworth, Introduction, in: A. B. Bosworth and E.J. Baynham (eds.), Alexander the

Great in Fact and Fiction, Oxford, 1-22, 11 (over twenty pages of Bud text).

15 Badian, Conspiracies passim and esp. 70-2 denies existence of most conspiracies against

Alexander illustrated in our sources (an exception is the Pages conspiracy). Instead, he makes Alexander

and his closest friends the busiest conspirators of Macedonia from 336 to 323 BC.

16 E. Badian, The Death of Parmenio, TAPhA 91 (1960) 324-38; P. Green, Alexander of Macedon,

London 1974, 339-49; a far more balanced account of Alexanders actions against Philotas is given by

another historian who is far from being an enthusiast of Philips son, R. Lane Fox, Alexander the Great,

London 1973, 288-91 (p. 289: It is absurd to idealize him [i.e. Philotas] as a martyr to Alexanders

ruthlessness simply because the histories explain so little).

Conspirators Companions - Bodyguards

Page 23

It is generally accepted that Philotas only error was not to notify the king about the

Dimnus conspiracy he had learnt about. It may seem an irony of history (or

historiography) that a tale preserved by three of the Alexander historians makes Philotas

father a false informer. Parmenio warned Alexander about an attempt to poison him

(Plut., Alex. 19; Arr., Anab. 2.4.8-11; Curt. 3.6.1-20

17

). Notwithstanding minor

discrepancies

18

, the historians agree that Parmenio attacked Alexanders most trusted

physician, Philip of Acarnania (BERVE no. 788). Alexander is held to have drunk an

allegedly poisonous cure which proved Philip not guilty. The king was convinced that

Parmenio had plotted against one of his most intimate friends, and this intrigue (or

mistake) brought disgrace on him. It has been suggested that the story may have been

invented by Philotas (or by his epigone admirer) to explain his failure to inform

Alexander of the Dimnus conspiracy: Parmenios son tried to behave cautiously so as to

avoid the risk of bringing another charge against innocent men

19

. In actual fact Curtius

reports that Philotas tried to exculpate himself in front of the assembled Macedonians by

remembering the false and distrusted accusation against Philip by Parmenio (Curt.

6.10.33-35). Parmenios attack on Philip of Acarnania receives, as usual, a longer

treatment by Curtius Rufus, who seems to have known a lot about the man, and who

characterizes him as very close to the king. Moreover, the Latin historian, while

introducing Philip, in a unusual way exploits motives of companionship and loyalty by

repeating words he uses elsewhere to designate the kings companions (Curt. 3.6.1: Erat

inter nobiles medicos ex Macedonia regem secutus Philippus, natione Acarnan, fidus admodum

regi: puero comes et custos salutis datus non ut regem modo sed etiam ut alumnum eximia caritate

diligebat - Among the famous physicians who had followed the king from Macedonia

was Philip, a native of Acarnania, most loyal to Alexander, made the kings companion

and the guardian of his health from boyhood, he loved him with extreme affection, not

only as his king, but even as a foster-king)

20

.

17 Diodorus (17.31.4-6) tells the same story without any mention of Parmenios involvement in the

affair; most likely so because of his abridgement of the sources.

18 Curtius makes Alexander take Philips medicine three days after he had received Parmenios letter.

Badian, Conspiracies, 60-1 rightly recognises this variant as a duplicate of the three days Alexander

needed to recover, after Philips remedy had been applied.

19 P. Treves, Philippos (63), RE 19.2 (1938) 2549-50: Es (i.e. the story of Parmenions intervention

against Philip) ist vielleicht ad maiorem gloriam Parmenions und damit, stillschweigend, zum Tadel

Alexanders erfunden oder ad maiorem gloriam einerseits der Geisteshhe des Knigs, andererseits der

Treue und Vorsicht des Parmenions. N.G.L. Hammond, Three Historians of Alexander the Great,

Cambridge 1983, 121, makes Cleitarchus the intermediary source. Cf.: W. Heckel, King and

Companions, in: J. Roisman (ed.) Brills Companion to Alexander the Great, Leiden-Boston 2003, 197-225

at 214.

20 According to Diodorus (17.31.6) the elevation of Philip to the circle of the closest Friends of the

king was due to the fact he had been able to cure him (tcv utov c tou civcotutou tv iv-

and assigned him to the most trusted among the Friends). Also Plutarch (Alex. 19.6) does not

Jacek Rzepka

Page 24

I cannot agree that the event is wholly invented: one should ask why was it that Philip

of Acarnania (and none of the great Macedonian nobles) was chosen to be the

instrument to exculpate Philotas? Most likely then, the story mirrors, in some way at

least, a real event: there was certainly a serious illness of Alexander and his

miraculous recovery after the medical intervention by Philip. A conflict between the

senior marshal of Alexander and his mothers most trusted doctor

21

is also plausible. We

can be sure that Parmenio was not (as for example Ernst BADIAN would like) an

innocent victim of an ancient Stalin

22

. The most questionable part of the legend is,

surely, the content of Parmenios letter denouncing Philip. One cannot be certain if the

written accusation is not also a fabrication. Curtius has been criticised for making

Parmenio send a letter to the king, because Arrian (2.4.4) indicates that the whole of the

Macedonian army was together at that time

23

. Parmenio may have not wanted,

however, to speak openly against Philip in the presence of Alexanders medical staff, in

which Philip played first fiddle. Nothing speaks, therefore, against a written

denunciation conveyed to Alexander by a friend of Parmenio or less likely by Parmenio

himself

24

.

The question is whether Philotas himself recalled it as an excuse during his trial (that

would mean that he confessed he had been informed about the Dimnus conspiracy) or

whether later critics of Alexander tried to exculpate Philotas and thus lay the blame on

Alexander

25

. Of course, the very sympathetic treatment of the Acarnanian in Curtius

may suggest that his picture of the physician is inherited from Alexander or his

entourage, rather than from Philotas.

necessarily mean that Philip belonged to the Companions/Friends of Alexander (this is not the place to

discuss whether the bodies labeled in our sources as hetairoi or philoi fully overlapped: this problem

deserves much more space and a separate treatment).

21 The Acarnanian origin of Philip and his care over Alexander in the latters boyhood hint that he

was originally employed by Olympias.

22 E. Badian, The Death of Parmenio, 324-38 omits the story of Parmenios intrigue against Philip.

By the way, it is worth remembering that most of the victims of Stalins purge of communist leaders were

not so innocent themselves.

23 Berve, no. 788.

24 Let us note that also Cebalinus looked (twice) for a suitable moment to bring news of the Dimnus

conspiracy secretly through an individual member of Alexanders staff (through Philotas: Curt. 6.7.17-18;

Diod.17.79.2-3 and then Metron: Curt. 6.7.22-3; Diod. 17.79.4-6). There is a slight difference of emphasis

between Diodorus and Curtius, who report the same event. Diodorus stresses that Cebalinus tried to pass

his news as soon as possible through the first trusted person he met, whereas Curtius, who also

understands that Philotas was involved by chance (Curt. 6.7.18: forte), underscores that Cebalinus had to

wait for an opportunity of a secret talk with one person.

25 However, it cannot be excluded that the content of Philotas speech is Curtius invention. The

controversy over the historicity of speeches included in Curtius (and in ancient historians generally) never

ends. Admittedly, the majority view is that most speeches and letters in historians are not authentic.

Conspirators Companions - Bodyguards

Page 25

If the episode of Philip of Acarnania was used by those who wanted to defend

Philotas, the king and his adherents certainly tried to present counter-arguments. It

seems that the spurious plot of Philip the Acarnanian was used, in intra-Macedonian

political discourse, as an excuse for the inactivity of Philotas in the face of the Dimnus

conspiracy: this was counter-balanced by a real and successful conspiracy of Bessus

against Darius III. The far-reaching symmetry in the way Curtius Rufus presents the

conspiracy of Bessus and the Philotas affair is striking. Both episodes are presented by

Curtius at length, with many details unknown to, or omitted by, other historians of

Alexander. Thus in the Philotas affair we have a plot of (ordinary) Macedonians known

to a Macedonian nobleman. This nobleman estimated the importance of the conspiracy

as low, and did not warn his king. In the conspiracy against Darius, which began only a

few months earlier, Curtius describes a plot of noble Persians that was rightly uncovered

from the inside by the Greek mercenary commander Patron. Up to that moment both

stories look similar. Yet Patron of Phocis proved himself loyal to Darius and uncovered

Bessus conspiracy (the first difference between the stories). Darius reaction to the news

was also strange. The Achaemenid king refused to punish Nabarzanes and Bessus, since

he tried to think the best of his followers.

Thus, we have two different, yet corresponding ways in which the information about

conspiracies is uncovered, and the way in which the two monarchs react to the

information results differs too. Darius childish belief in the innocence of his aristocrats

caused his premature death, whereas Alexanders cold decision to foil all plots against

him saved his life. Was this not a good reason for a preventive slaughter of his

aristocrats?

26

Both the striking similarities and the direct contrasts are hardly accidental, although

neither similarities nor contrasts prove that the account of Darius last days as we have

them portrayed in Curtius Rufus was created to explain Alexanders action against

Philotas. Yet, if we read both accounts throughout, we can notice more resemblances,

both in diction and in the terminology used.

As I suggested above, already Curtius description of Philip of Acarnania focuses on

his intimacy with Alexander: we can see then the triple statement of Philips relation to

Alexander: erat secutus (had followed), comes (a companion), custos (a guardian). It is

a rather unusual concentration, and one should note that the terms comes (comites) and

custos (custodes) do not recur too often in Curtius Rufus. When used in a Macedonian

context

27

, the word is generally narrowed to custos (custodes, custodia) corporis and usually

26 Here I have to agree with E. Badian, Conspiracies, 53-75 that Alexander sometimes (re-)acted

against conspiracies that did not exist.

27 In a Persian context custodia corporis can refer to Darius elite cavalry (Curt. 3.9.4) or any larger

bodyguard formation (Curt. 6.4.9).

Jacek Rzepka

Page 26

denotes a somatophylakes of Alexander (see 4.13.19; 6.7.15; 6.11.8; 8.6.21; 9.6.4; 9.8.23;

10.6.1, but cf. ex armigeris 6.8.17). Let us note that the assembly deliberating on Philotas

crime was incited by Alexanders bodyguards

28

, who were also most persistent in

demanding capital punishment for Parmenios son.

Of course, Curtius rendering of Greek terms into Latin sometimes can pose

problems; thus, custodia corporis sometimes refers to the Royal Pages (e.g. Curt. 5.1.42;

10.5.8), or, when it occurs in the composite form armigeri corporisque custodes (Curt.

8.1.2), it is rather difficult to decide which element describes the somatophylakes and

which the hetairoi.

Curtius also applies Latin translations of Greco-Macedonian court and army titles to

the barbarians at the Alexander court. For example Oxyathres, Darius brother (BERVE

586), was enlisted among custodes corporis (Curt. 7.5.40):

Et Alexander Oxathren, fratrem Darei, quem inter corporis custodes habebat,

propius iussit accedere tradique Bessum ei, ut cruci adfixum mutilatis auribus

naribusque sagittis configerent barbari adservarentque corpus, ut ne aves quidem

contingerent.

But Alexander ordered Oxathres, the brother of Darius, whom he had

among his bodyguards, to come nearer, and that Bessus be delivered to

him, in order that, bound to a cross after his ears and his nose had been

cut off, the barbarians might pierce him with arrows and so guard his body

that not even the birds could touch it.

It is worth stressing that the context in which Curtius introduces Oxyathres as a

corporis custos is not unrelated to a conspiracy. Although Oxyathres was made an extra

bodyguard of Alexander, he mutilates Bessus as Darius avenger, and thus puts an end

to the conspiracy that had destroyed his earlier sovereign

A little earlier, when Curtius mentions Oxyathres admission to the hetairoi, his

language is not strictly technical (Curt. 6.2.11): Oxydates erat nobilis Perses, qui a Dareo

capitali supplicio destinatus cohibebatur in vinculis; huic liberato satrapeam Mediae attribuit,

fratremque Darei recepit in cohortem amicorum omni vetustae claritatis honore servato

(Oxydates was a Persian noble who was being kept in bonds, because he had been

destined by Darius for capital punishment. Alexander freed him and conferred upon him

the satrapy of Media, and thus he received a brother of Darius into the band of his

28 Curt. 6.11.8: Tum vero universa contio accensa est, et a corporis custodibus initium factum clamantibus

discerpendum esse parricidam manibus eorum Then truly the whole assembly was inflamed, and a

beginning was made by the bodyguards, who shouted that the traitor ought to be torn to pieces by their

own hands.

Conspirators Companions - Bodyguards

Page 27

Friends with the maintenance of all the honour due to his ancient lineage). Curtius

renders here Greek rather imprecisely, cohors amicorum means the Companion Cavalry,

as can be inferred from a related passage of Plutarch Alexander (Plut., Alex. 43.7: tov o

ocov u0pqv c tou ctipou vccv - He admitted his [Darius] brother

Exathres to the Companions)

29

. Diodorus calls Oxyathres unit doryphoroi or rabdouchoi,

and is very explicit about its Persian character (17, 77, 4: ki ptov cv cpi tqv qv

poouou oicvc, cit tou civcotutou tv <oivv vopv oopuopcv

tcv, cv o v ki pciou oco u0pq - and Alexander had once Asian

wandbearers at the court, then he arrayed the best of the Asians as spearbearers, among

them was also Oxathres, the brother of Darius)

30

. There is no need to see in the hoi peri

ten aulen rabdouchoi aa another set of somatophylakes. Rather, they were an elite unit of the

army as e.g. the Royal Agema.

31

Curtius exploits the rhetorical possibilities provided by placing the word comes into a

certain context once again in his account of the case of Amyntas, who, having been

accused of high treason himself, accused his own brother Polemon of the same crime

(Curt. 7.2.6: Moveratque iam regem quoque, non contionem modo, sed unus erat implacabilis

frater, qui terribili vultu intuens eum Tum, ait demens, lacrimare debueras, cum equo calcaria

subderes, fratrum desertor et desertorum comes. Miser, quo et unde fugiebas? Effecisti, ut reus

capitis accusatoris uterer verbis. - And now he had affected the king also, and not only

the assembly, but his brother alone was inexorable, and gazing at him with a terrifying

expression exclaimed: Then, madman, is when you ought to have wept, when you were

applying spurs to your horse, a deserter of your brothers and a companion of deserters.

Wretch, whither were you fleeing and from whom? You have forced me, on trial for my

life, to use the words of an accuser.

Yet, the most striking analogy can be seen in Curtius account of the conspiracy of

Bessus against Darius (5.8.111). It will be necessary to quote the story of how Patron

29 I would not like to suggest by this that Alexanders Friends are identical with his Companions.

Rather, I believe that these two more or less formalized bodies partly overlapped, but that their

composition was different. I hope to return to this important problem in a separate study.

30 Not dissimilar is a case of four Sogdians serving as corporis custodes (Curt. 7, 10, 9).

31 These units in which Oxyathres served strongly suggest that the army of Alexander was never

intended to be a melting pot for the peoples of Alexanders empire. Rather, barbarian troops retained their

own organization, even if they had been taught the Macedonian way of fighting. See: P.A. Brunt,

Alexanders Macedonian Cavalry, JHS 83, 1963, 27-46, 45; A.B. Bosworth, Alexander and the

Iranians, JHS 100 (1980) 1-21; P.A. Brunt, Arrian. Anabasis of Alexander (Loeb Classical Library), vol. 2,

Cambridge, Mass. 1983, 220 (in commentary on Arr., Anab. 7, 6, 2-5); E. Borza, Ethnicity and Cultural

Policy in Alexanders Court, AncW 23 (1992) 21-5; 21 (= C.G. Thomas (ed.), Makedonika: Essays by

Eugene N. Borza, Claremont, 1995, 149-158). N.G.L. Hammond, The Text and the Meaning of Arrian vii

6.2-5, JHS 103, 1983, 139-144, arguing for the integration of Asians into mixed units is far from being

convincing (he apparently is inspired by W.W. Tarns idea of Alexander striving for the unity of mankind.

Jacek Rzepka

Page 28

revealed the plot to Darius. Great emphasis was laid on the ranks and titles used in

Darius army and court:

(5.11.1) Patron autem, Graecorum dux, praecipit suis, ut arma, quae in sarcinis

antea ferebantur, induerent ad omne imperium suum parati et intenti. (2) Ipse

currum regis sequebatur occasioni imminens adloquendi eum: quippe Bessi facinus

praesenserat. Sed Bessus id ipsum metuens, custos verius quam comes, a curru non

recedebat. (3) Diu ergo Patron cunctatus ac saepius sermone revocatus, inter fidem

timoremque haesitans regem intuebatur. (4) Qui ut tandem advertit oculos,

Bubacen spadonem inter proximos currum sequentem percontari iubet, numquid

ipsi velit dicere. Patron se vero, sed remotis arbitris loqui velle cum eo respondit

iussus que propius accedere sine interprete (5) nam haud rudis Graecae linguae

Dareus erat - Rex, inquit ex L milibus Graecorum supersumus pauci, omnis

fortunae tuae comites et in hoc tuo statu idem, qui florente te fuimus, quascumque

terras elegeris, pro patria et domesticis rebus petituri. Secundae adversaeque res

tuae copulavere nos tecum. (6) Per hanc fidem invictam oro et obtestor, in nostris

castris tibi tabernaculum statui, nos corporis tui custodes esse patiaris. Omisimus

Graeciam, nulla Bactra sunt nobis, spes omnis in te: utinam etiam ceteris esset!

Plura dici non attinet. Custodiam corporis tui externus et alienigena non

deposcerem, si crederem alium posse praestare.

(7) Bessus quamquam erat Graeci sermonis ignarus, tamen stimulante

conscientia indicium profecto Patronem detulisse credebat: et interpretes celato

sermone Graeci exempta dubitatio est. (8) Dareus autem, quantum ex voltu concipi

poterat, haud sane territus percontari Patrona causam consilii, quod adferret,

coepit. Ille non ultra differendum ratus Bessus inquit et Nabarzanes insidiantur

tibi: in ultimo discrimine et fortunae tuae et vitae hic dies aut parricidis aut tibi

futurus <est> ultimus.

(9) Et Patron quidem egregiam conservati regis gloriam tulerat. (10) Eludant

[vide] licet, quibus forte temere humana negotia volvi agique persuasum est;

<equidem fato crediderim> nexuque causarum latentium et multo ante

destinatarum suum quemque ordinem immutabili lege percurrere: (11) Dareus

certe respondit, quamquam sibi Graecorum militum fides nota sit, numquam

tamen a popularibus suis recessurum. Difficilius sibi esse damnare quam decipi.

Quicquid fors tulisset, inter suos perpeti malle quam transfugam fieri. Sero se

perire, si salvum esse milites sui nollent. (12) Patron desperata regis salute ad eos,

quibus praeerat, rediit omnia pro fide experiri paratus.

Conspirators Companions - Bodyguards

Page 29

(5.11.1) But Patron, the leader of the Greeks ordered his men to put on

their arms, which before were carried with the baggage, and to be ready

and on the alert for every order of his. (2) He himself was following the

kings chariot, eager for a chance to speak to him; for he had a

premonition of the evil design of Bessus. But Bessus, in fear of that very

thing, did not move from the chariot, acting as a guard rather than as a

companion. (3) Therefore Patron, after waiting for a long time and

often being restrained from speaking, kept his eyes fixed upon the king,

wavering between loyalty and fear. (4) When at last the king turned

towards him, he ordered Bubaces, a eunuch who was following the

chariot among the nearest Darius, to ask the Greek whether he wished to

say anything to him. Patron replied that he did in fact wish to talk with

him, but without witnesses, and when bidden to come nearer without an

interpreter for Darius was not unacquainted with the Greek language

he said: (5) My king, out of 50,000 Greeks we are the few that are left,

companions of all your fortune, and in your present state unchanged

from what we were in your prosperity, ready to seek, in place of our

native land and our homes, whatever lands you shall select. (6) Your

prosperity and adversity have linked us with you. By this invincible

loyalty I beg and conjure you, pitch your tent in our camp; suffer us to be

your bodyguards. We have abandoned Greece, no Bactra belong to us,

all our hope is in you; would that it were true also of the rest! It is

needless to say more. I, a foreigner and alien race should not demand the

guard of your person, if I believed that another could guarantee it.

(7) Although Bessus was unacquainted with the Greek language, yet,

pricked by conscience, he believed that Patron had surely revealed his

plot; and since the words of the Greek were concealed from interpreters,

any doubt was removed. (8) Darius, however, being so far as could be

inferred from his expression not at all alarmed, began to question Patron

as to the reason for the advice which he brought. The Greek, thinking

that there was no room for further delay, said Bessus and Nabarzanes

are plotting against you, your fortune and your life are in extreme

danger, this day will be the last for the traitors or for you.

(9) And in fact Patron had gained the illustrious glory of saving the

king. (10) Those may scoff at my belief who happily are convinced that

human affairs roll on and take place by mere chance, or that each man

runs his ordered course in accordance with a combination of hidden

causes determined long beforehand by an immutable law; (11) at any

rate, Darius replied that although the loyalty of the Greek soldiers was

Jacek Rzepka

Page 30

well known to him, yet he would never separate himself from his own

countrymen, that it was more difficult for him to condemn than to be

deceived. Whatever Fortune should offer him he preferred to endure

among his own subjects rather to become a deserter. He was perishing

too late, if his own soldiers did not wish him to be saved. (12) Patron,

despairing of the kings safety, returned to those whom he commanded,

prepared to submit to every possible trial to the best of his loyalty.

In this account we meet a false custos in the person of Bessus whereas the Greeks of

Darius, although loyal soldiers, were never admitted to the corporis custodia. As in other

cases (Philip of Acarnania, Polemon, Oxathres) the term is used non-technically.

Therefore the terms are used purely rhetorically. The prime suspect for the use of these

words seems to be Curtius Rufus. Yet we should notice that traces of the same type of

rhetoric can be found in other historians of Alexander the Great. The Greek original of

comes/comites, the word hetairos/hetairoi is strikingly absent from Diodorus XVII

(whereas he does use the term in books XVIII to XX, which are based on Hieronymus).

In Book XVII, the kings most trusted collaborators are invariably called philoi.

32

Companion cavalry is a few times referred to as hetairoi, but in a purely military sense

(17.77 and 100; cf. 17.37.2: hetairike hippos). What may surprise us is that Diodorus uses

the word to describe the court of Bessus (actually inherited from Darius)

Diod. 17.83:

ooo o utov vococie oic to 0co 0uoc ki tou iou pev c tqv

civ ktu tov otov oiqvc0q po tiv tv ctipv, vo oupv- Bessus,

proclaimed himself king, sacrificed to the gods, and invited his friends to a banquet. In

the course of the drinking, he fell into argument with one of the Companions, Bagodaras

by name.

The context again is clear: a rivalry of Persian nobles over the issue of Bessus

usurpation. However, in contrast to Curtius Rufus, Diodorus does not exploit this theme

according to the principles of oratory. Since he does not use the term hetairoi for

Macedonians in his Book XVII, but does so repeatedly in his Hellenistic books, he

evidently did not find the word in his source for Alexander

33

.

To conclude: Although Curtius Rufus rarely uses technical terms for Companions or

bodyguards, he most often does so in his accounts of conspiracies. Furthermore, Curtius

eagerly inserts the words comes and (corporis) custos into rhetorical contexts. Therefore, he

exploits both terms in contrasts, metaphors, comparisons and paradoxes. Traces of

similar terminology in Diodorus (and in Plutarch where he deals with Oxyathres) may

32 J. Hornblower, Hieronymus of Cardia, Oxford 1981, 34.

33 P. Briant, Darius, 197-8 notices that Curtius plays with the motive of fidelity throughout this

passage (the concept of fidelity recurs with notable intensity: 5.8.3; 5.10.7; 5.11.6; 5.11.11).

Conspirators Companions - Bodyguards

Page 31

suggest that it was not Curtius Rufus who invented the rhetoric of companionship,

guardianship and (dis-) loyalty. Given the structural resemblance between the Philotas

affair and Parmenios mistaken charge against Philip of Acarnania, or between the

conspiracy of Dimnus not revealed by Philotas and the conspiracy of Bessus revealed by

Patron, and numerous cross-references between these stories, one should conclude that

the detailed picture of these events as transmitted to us by Curtius was shaped during the

reign of Alexander. The stories created for the propaganda struggle were incorporated by

at least one of the lost historians of Alexander. This does not exclude the possibility that

it might have been Patron himself who provided Alexander and his propaganda-makers

with the material to elaborate. Moreover, we can imagine that Patron, when he arrived

at the Macedonian camp, was an ideal instrument for Alexander to explain his attitude

toward the distrusted Macedonian elite. Certainly Patron was prone to exaggerate his

role in the last days of Darius; certainly he was pleased by the reception of his message

by the king and among the Macedonians; but certainly, also, he did think about himself

as a reliable witness of Darius death. However, the language of the Patron Darius

episode was the language of the same source, from which Curtius has taken his account

of the conspiracies against Alexander.

JACEK RZEPKA

You might also like

- The Money Masters PDFDocument31 pagesThe Money Masters PDFvenurao1100% (6)

- Part 01-04 - The Future Is Calling. G. Edward GriffinDocument89 pagesPart 01-04 - The Future Is Calling. G. Edward GriffinIonut Dobrinescu100% (1)

- Fighting BookDocument230 pagesFighting Bookintense4dislike100% (3)

- A.MIG-6015 Illustrated Weathering Guide Panzer IV Ausf H PDFDocument22 pagesA.MIG-6015 Illustrated Weathering Guide Panzer IV Ausf H PDFMarioScicluna100% (2)

- Brill Ancient Greek LanguageDocument1 pageBrill Ancient Greek Languageapi-235372025No ratings yet

- Geoffrey Ashe - The Origins of The Arthurian LegendDocument24 pagesGeoffrey Ashe - The Origins of The Arthurian LegendagarratecatalinaNo ratings yet

- Unit STR & Base SizeDocument2 pagesUnit STR & Base SizeFuncrusher100% (2)

- The Battle Agaisnt The Oppressors - 073412Document27 pagesThe Battle Agaisnt The Oppressors - 073412Jiemalyn Asis GregorioNo ratings yet

- 23 GIRLS Tennis BURLCO Tournament ResultsDocument5 pages23 GIRLS Tennis BURLCO Tournament ResultsChris NNo ratings yet

- Skyhawk BuNo. 154908 A4G 887 RAN FAA Now Draken A-4K N144EM History pp154Document154 pagesSkyhawk BuNo. 154908 A4G 887 RAN FAA Now Draken A-4K N144EM History pp154SpazSinbad100% (1)

- Bremmer Attis 1Document34 pagesBremmer Attis 1Anonymous 77zvHWs100% (1)

- Robinson - Alexander's IdeasDocument20 pagesRobinson - Alexander's IdeasJames L. Kelley100% (1)

- Marathon: How One Battle Changed Western CivilizationFrom EverandMarathon: How One Battle Changed Western CivilizationRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (10)

- Aelius Aristides Between Greece Rome, and The GodsDocument341 pagesAelius Aristides Between Greece Rome, and The GodsBuğra Kağan AkçaNo ratings yet

- A.B. Bosworth - Errors in ArrianDocument24 pagesA.B. Bosworth - Errors in ArrianltmeroneNo ratings yet

- Lettera AristeaDocument15 pagesLettera AristeadanlackNo ratings yet

- Searching For A Theory of Public DiplomacyDocument24 pagesSearching For A Theory of Public DiplomacyLungu AdrianaNo ratings yet

- E BaynhamDocument27 pagesE Baynhami1958239No ratings yet

- PDFDocument406 pagesPDFthierry100% (1)

- Laborator 2 - Localizarea punctelor într-un poligon convexDocument122 pagesLaborator 2 - Localizarea punctelor într-un poligon convexBelciu AndraNo ratings yet

- Brill Alexander PDF PDFDocument264 pagesBrill Alexander PDF PDFGena Litvak100% (5)

- The Crab Cannery Ship and Other - Kobayashi TakijiDocument322 pagesThe Crab Cannery Ship and Other - Kobayashi TakijiDianaNo ratings yet

- GARDINER, Alan - The Kadesh Inscriptions of Ramesses IIDocument61 pagesGARDINER, Alan - The Kadesh Inscriptions of Ramesses IISamara Dyva100% (4)

- War, Women, and Druids: Eyewitness Reports and Early Accounts of the Ancient CeltsFrom EverandWar, Women, and Druids: Eyewitness Reports and Early Accounts of the Ancient CeltsRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (4)

- Etruscan HistoriographyDocument30 pagesEtruscan Historiographypratamanita widi rahayuNo ratings yet

- The Power Struggle of The Diadochoi in Babylon, 323 BC : RringtonDocument44 pagesThe Power Struggle of The Diadochoi in Babylon, 323 BC : RringtonAbriNo ratings yet

- 10 2307@267080Document3 pages10 2307@267080Felipe MontanaresNo ratings yet

- Barry Baldwin. The Date of A Circus Dialogue. Revue Des Études Byzantines, Tome 39, 1981. Pp. 301-306.Document7 pagesBarry Baldwin. The Date of A Circus Dialogue. Revue Des Études Byzantines, Tome 39, 1981. Pp. 301-306.Patrologia Latina, Graeca et OrientalisNo ratings yet

- Death ConstantineDocument9 pagesDeath ConstantineEirini PanouNo ratings yet

- Department of The Classics, Harvard UniversityDocument28 pagesDepartment of The Classics, Harvard UniversityViktor LazarevskiNo ratings yet

- Bosworth1990 PDFDocument13 pagesBosworth1990 PDFSafaa SaiedNo ratings yet

- Reflecting on Cyrus the Great Conference DebatesDocument12 pagesReflecting on Cyrus the Great Conference DebatesDaniel de FrançaNo ratings yet

- His BiographersDocument10 pagesHis BiographersAndreas ThrasyvoulouNo ratings yet

- Nicanor Son of Balacrus: Waldemar HeckelDocument12 pagesNicanor Son of Balacrus: Waldemar HeckelAbriNo ratings yet

- Alexander and The Amazon Queen - Márta MundingDocument18 pagesAlexander and The Amazon Queen - Márta MundingSonjce Marceva100% (1)

- Capps E Page E T and Rouse D H W Thucydides History of The Peloponnesian War Book I and IIDocument512 pagesCapps E Page E T and Rouse D H W Thucydides History of The Peloponnesian War Book I and IIMarko MilosevicNo ratings yet

- Franz Steiner Verlag Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve and Extend Access To Historia: Zeitschrift Für Alte GeschichteDocument26 pagesFranz Steiner Verlag Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve and Extend Access To Historia: Zeitschrift Für Alte GeschichteRafael PinalesNo ratings yet

- Crescent and The Rose Islam and England During The RenaissanceDocument29 pagesCrescent and The Rose Islam and England During The RenaissancesaitmehmettNo ratings yet

- Franz Steiner Verlag Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve and Extend Access To Historia: Zeitschrift Für Alte GeschichteDocument13 pagesFranz Steiner Verlag Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve and Extend Access To Historia: Zeitschrift Für Alte GeschichteRafael PinalesNo ratings yet

- Badian. HarpalusDocument29 pagesBadian. HarpalusCristina BogdanNo ratings yet

- ER1998 v6 2I Parisious - Postscript To Tudor Rose TheoryDocument4 pagesER1998 v6 2I Parisious - Postscript To Tudor Rose TheoryJulie WilburnNo ratings yet

- The Unfriendly CorcyraeansDocument12 pagesThe Unfriendly CorcyraeansXiaoNo ratings yet

- Notices of Books: of The Macedonian Army. Berkeley Etc.: UniverDocument2 pagesNotices of Books: of The Macedonian Army. Berkeley Etc.: UniverRafael PinalesNo ratings yet

- Ctesias' Persica: Persian Decadence in Greek HistoriographyDocument20 pagesCtesias' Persica: Persian Decadence in Greek HistoriographyMatheus Moraes MalufNo ratings yet

- Alfred Gudeman. Literary Frauds Among The RomansDocument25 pagesAlfred Gudeman. Literary Frauds Among The RomansΘεόφραστοςNo ratings yet

- De Blois Eis BasileaDocument10 pagesDe Blois Eis BasileaSteftyraNo ratings yet

- S. A. Sterz, The Emperor Hadrian and Intelectuals, ANRW 2.34.1 (1993)Document17 pagesS. A. Sterz, The Emperor Hadrian and Intelectuals, ANRW 2.34.1 (1993)Julija ŽeleznikNo ratings yet

- Artaxerxes' 20th Year - 455 BCDocument7 pagesArtaxerxes' 20th Year - 455 BCJonathan PhotiusNo ratings yet

- Legends of the Greek Lawgivers: How History Shifted into MythDocument11 pagesLegends of the Greek Lawgivers: How History Shifted into MythDániel BajnokNo ratings yet

- Achyron or Proasteion. The Location and Circumstances of Constantine's Death PDFDocument9 pagesAchyron or Proasteion. The Location and Circumstances of Constantine's Death PDFMariusz MyjakNo ratings yet

- 25010818Document17 pages25010818johnkalespiNo ratings yet

- The 20th Year of Artaxerxes and The Seventy Weeks of DanielDocument7 pagesThe 20th Year of Artaxerxes and The Seventy Weeks of DanielKomishinNo ratings yet

- The Classical Review examines Homer's IliadDocument7 pagesThe Classical Review examines Homer's IliadFranchescolly RibeiroNo ratings yet

- Arrian at The Caspian GatesDocument13 pagesArrian at The Caspian GatesAndresSaezGeoffroyNo ratings yet

- JW Rich Augustus and The Spolia OpimaDocument43 pagesJW Rich Augustus and The Spolia OpimaMiddle Republican HistorianNo ratings yet

- Vickers, Persepolis, Vitruvius and The Erechtheum Caryatids. The Iconography of MedismDocument27 pagesVickers, Persepolis, Vitruvius and The Erechtheum Caryatids. The Iconography of MedismClaudio CastellettiNo ratings yet

- Some Observations On The Origin of Byzantine-Persian Political SymbiosisDocument13 pagesSome Observations On The Origin of Byzantine-Persian Political SymbiosistheodorrNo ratings yet

- Patricii ValentinianiiiDocument16 pagesPatricii ValentinianiiiJaShongNo ratings yet

- Literary Frauds among the Romans ExaminedDocument26 pagesLiterary Frauds among the Romans Examinedgrzejnik1No ratings yet

- Bosworth-1986-Alexander The Great and TheDocument12 pagesBosworth-1986-Alexander The Great and TheGosciwit MalinowskiNo ratings yet

- Greco BactriaDocument27 pagesGreco BactriaAndrew WardNo ratings yet

- Bulletin of The School of Oriental and African Studies: L'empire Perse: de Cyrus À Alexandre. 1248 PPDocument4 pagesBulletin of The School of Oriental and African Studies: L'empire Perse: de Cyrus À Alexandre. 1248 PPSajad AmiriNo ratings yet

- The Johns Hopkins University Press Transactions of The American Philological Association (1974-2014)Document18 pagesThe Johns Hopkins University Press Transactions of The American Philological Association (1974-2014)Beethoven AlvarezNo ratings yet

- The Heirs of Artabazus The Satrapy of DaDocument25 pagesThe Heirs of Artabazus The Satrapy of DametafujinonNo ratings yet

- Treatment of Prisoners of War in Ancient Greece from Origins to Roman ConquestDocument4 pagesTreatment of Prisoners of War in Ancient Greece from Origins to Roman ConquestSafaa SaiedNo ratings yet

- Sedley-1997-The Ethics of Brutus andDocument13 pagesSedley-1997-The Ethics of Brutus andFlosquisMongisNo ratings yet

- The Athenian Expedition To Melos in 416 B.C.Document35 pagesThe Athenian Expedition To Melos in 416 B.C.tamirasagNo ratings yet

- A Probable Italian Source of Shakespeare's "Julius Cæsar"From EverandA Probable Italian Source of Shakespeare's "Julius Cæsar"No ratings yet

- The Fall of Troy (Barnes & Noble Library of Essential Reading)From EverandThe Fall of Troy (Barnes & Noble Library of Essential Reading)No ratings yet

- Michailidis AbecedarDocument10 pagesMichailidis Abecedarapi-235372025No ratings yet

- Strootman Kings and CitiesDocument16 pagesStrootman Kings and Citiesapi-235372025100% (1)

- Strootman Hellenistic CourtDocument2 pagesStrootman Hellenistic Courtapi-235372025No ratings yet

- Strootman Queen of KingsDocument30 pagesStrootman Queen of Kingsapi-235372025No ratings yet

- Strootman Hellenistic Court Under The SeleucidsDocument27 pagesStrootman Hellenistic Court Under The Seleucidsapi-235372025No ratings yet

- Strootman SeleucidDocument6 pagesStrootman Seleucidapi-235372025No ratings yet

- Rzepka Philip II of Macedon Garrison of NaupactusDocument10 pagesRzepka Philip II of Macedon Garrison of Naupactusapi-235372025No ratings yet

- Katadesmos FinalDocument31 pagesKatadesmos Finalapi-235372025No ratings yet

- Units of Alexanders Army PDFDocument18 pagesUnits of Alexanders Army PDFjaccho`No ratings yet

- Marcus Templar Nato Is A Bona Fide Military AllianceDocument6 pagesMarcus Templar Nato Is A Bona Fide Military Allianceapi-235372025No ratings yet

- Marcus Templar Fallacies and Facts On The Macedonian IssueDocument23 pagesMarcus Templar Fallacies and Facts On The Macedonian Issueapi-235372025No ratings yet

- Strootman Antiochos IIIDocument3 pagesStrootman Antiochos IIIapi-235372025No ratings yet

- Strootman Thessalian CavalryDocument19 pagesStrootman Thessalian Cavalryapi-235372025No ratings yet

- Marcus Templar Skopjes Nato AdventuresDocument66 pagesMarcus Templar Skopjes Nato Adventuresapi-235372025No ratings yet

- Rzepka Koine Ekklesia in Diodorus Siculus General Assembly MacedoniansDocument24 pagesRzepka Koine Ekklesia in Diodorus Siculus General Assembly Macedoniansapi-235372025No ratings yet

- Marcus Templar Macedonia The Lung of GreeceDocument21 pagesMarcus Templar Macedonia The Lung of Greeceapi-235372025No ratings yet

- 001 Skopje S Political EfficiencyDocument44 pages001 Skopje S Political Efficiencyapi-235372025No ratings yet

- Marcus Templar What If The Annan Plan and TurkeyDocument2 pagesMarcus Templar What If The Annan Plan and Turkeyapi-235372025No ratings yet

- Marcus Templar Eliminating Opposition One Way or AnotherDocument5 pagesMarcus Templar Eliminating Opposition One Way or Anotherapi-235372025No ratings yet

- Marcus Templar Fallacies and Facts On The Macedonian IssueDocument23 pagesMarcus Templar Fallacies and Facts On The Macedonian Issueapi-235372025No ratings yet

- Marcus Templar Eliminating Opposition One Way or AnotherDocument5 pagesMarcus Templar Eliminating Opposition One Way or Anotherapi-235372025No ratings yet

- Marcus Templar Nato Is A Bona Fide Military AllianceDocument6 pagesMarcus Templar Nato Is A Bona Fide Military Allianceapi-235372025No ratings yet

- Marcus Templar Macedonia The Lung of GreeceDocument21 pagesMarcus Templar Macedonia The Lung of Greeceapi-235372025No ratings yet

- Marcus Templar Skopjes Nato AdventuresDocument66 pagesMarcus Templar Skopjes Nato Adventuresapi-235372025No ratings yet

- 001 Skopje S Political EfficiencyDocument44 pages001 Skopje S Political Efficiencyapi-235372025No ratings yet

- Katadesmos FinalDocument31 pagesKatadesmos Finalapi-235372025No ratings yet

- Brill Companion To MacedonDocument1 pageBrill Companion To Macedonapi-235372025No ratings yet

- Lefkowitz and Rogers Black Athena RevisitedDocument272 pagesLefkowitz and Rogers Black Athena Revisitedapi-235372025No ratings yet

- The Chemist - Meyer, StephenieDocument20 pagesThe Chemist - Meyer, StephenieSalman AkramNo ratings yet

- Best Memorial (Respondent)Document9 pagesBest Memorial (Respondent)zatarra_12100% (3)

- Đề tiếng anhDocument8 pagesĐề tiếng anhsusohiiNo ratings yet

- Thayer US Aircraft Carrier To Visit Da Nang On 5 March 2020Document5 pagesThayer US Aircraft Carrier To Visit Da Nang On 5 March 2020Carlyle Alan ThayerNo ratings yet

- GSDFR 624-1 PromotionsDocument11 pagesGSDFR 624-1 PromotionsMark CheneyNo ratings yet

- The Coins of Philip Ii and Alexander The Great and Their Pan-HellenicpropagandaDocument12 pagesThe Coins of Philip Ii and Alexander The Great and Their Pan-HellenicpropagandanaglaaNo ratings yet

- Cybele and Attis From The Phrygian CragsDocument26 pagesCybele and Attis From The Phrygian CragsNatália HorváthNo ratings yet

- CD Mock 9Document57 pagesCD Mock 9ADITYANo ratings yet

- Schofield M. Euboulia in The Iliad CQ 36 (1986), 6-31Document27 pagesSchofield M. Euboulia in The Iliad CQ 36 (1986), 6-31Nikos HarokoposNo ratings yet

- China-Pakistan Relations - Wikipedia PDFDocument82 pagesChina-Pakistan Relations - Wikipedia PDFAnia Seher0% (1)

- Veterans Crisis Line Fact SheetDocument1 pageVeterans Crisis Line Fact SheetAnonymous Pb39klJNo ratings yet

- Source:: Content From Brown University., Used Per TermsDocument1 pageSource:: Content From Brown University., Used Per TermsjayNo ratings yet

- Nonfiction Reading TestDocument6 pagesNonfiction Reading TestClaudene GellaNo ratings yet

- The United Nations Is An OrganizationDocument4 pagesThe United Nations Is An OrganizationRachell BonetteNo ratings yet

- The Name Is BondDocument1 pageThe Name Is BondabdulmusaverNo ratings yet

- Darklight Manual DraftDocument28 pagesDarklight Manual DraftfreemallocNo ratings yet

- E8 - HW Unit 5 - Test 1Document2 pagesE8 - HW Unit 5 - Test 1Minh ThiệnNo ratings yet