Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Carax

Uploaded by

paguro82Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Carax

Uploaded by

paguro82Copyright:

Available Formats

Film-Philosophy 16.

1 (2012)

Film-Philosophy ISSN 1466-4615 243

Review: Alban Pichon (2009) Le cinema de Leos Carax.

Lexperience du dj-vu. Lormont: Le Bord de leau

editions, 268 pp.

Daniele Rugo

1

Lexperience du dj-vu is an imaginative and exhaustive analysis of the

work of the former enfant terrible of French Cinema, Leos Carax.

Throughout the book Pichon convincingly manages to move beyond the

categories usually associated with Caraxs work namely the Cinma du

look and the Neo-Baroque to propose a distinctively fresh approach.

Pichon opens his highly original volume by saying that in Caraxs

films the beginnings are never what they seem to be: they actually are a

matter of repetition or continuation

(3). To those readings that define

Caraxs work on the basis of slick visual style or that stress the sense of

marvel often provoked by his films, Pichon responds that the cinema of

Carax attracts our attention because it provides an entrance into the illusion

of beginnings, achieved through a constant intertwining of sensorial and

cinematic memory.

The book covers Carax entire oeuvre, which stretches across almost

thirty years, four long features (Boy meets Girl (1984), Mauvais

Sang(1986), Les amants du Pont-Neuf (1991), Pola X (1991)) and four

shorts (Strangulation Blues (1980), Sans titre (1997), My Last Minute

(2006), Merde (2008)). Pichon organizes his argument in three parts. Under

the title Constants, the first set of remarks grounds the analysis by

illustrating the elements around which Carax filmography revolves.

Examining the regularities that punctuate Caraxs formal and thematic

choices, Pichon stresses the presence of a reflexive ambiguity. The titles of

the four sections Circulations; Everyday the same water; Encounter and

recognition; The detours of language symbolically embrace the paradoxes

that will guide the book. The second part explores the French directors

relation to the history of cinema, attempting to delineate a genealogy that

moves from the golden age of silent film to the nouvelle vague, but also

considers in a wider context the importance of cinematographic memory. In

the last section From memory to history Pichon writes since Caraxs

work traces and reactivates a number of problematic aspects of past cinema,

one could say that it rejoins the history of cinema (191). Following the

Godard of Histoire(s) though, Pichon adds that the presentation of the

history of cinema performed by Carax is always only the presentation of one

of many possible histories. The question of the history of cinema becomes

1

Golsmiths, University of London: dan.rugo@gmail.com

Film-Philosophy 16.1 (2012)

Film-Philosophy ISSN 1466-4615 244

then a matter of memory and transmission, opening therefore a reflection on

the death and resurrection of cinema. Through more or less disguised

citations (in Mauvais Sang the character played by Binoche, called Anna,

looks and acts like a young Karina) and poetic statements, Carax places

himself on one side as the witness of this death and on the other as the

privileged survivor, who indicates a new beginning.

It is in the third and densest part that Pichon articulates his main thesis

more explicitly and it is here that the argument touches more closely on

philosophical issues. The notion of dj-vu, which forms the center of

Pichons critical approach often expressed in the forms of souvenir of the

present (an expression used by Alex in Boy Meets Girl) or false

recognition is derived largely from Bergsons work (filtered through

Deleuzes second book on cinema[for example Deleuze, 2005, p.77]). The

entire conceptual framework of this final part of Lexperience du dj-vu

rests on an appropriation of the French philosophers reflection on the

paradoxical nature of paramnesia. Pichons starting point is the Bergsonian

intuition of the duplicitous nature of our perception of events and time,

In a normal state of reception only the image of the present as present

accesses conscience, while the second the image as past does not,

since it could not be of any use. Nevertheless there are occasions when

we become conscious of the double dimensions of present time, which

then appears to us both present and past (234).

Faithful to the Bergsonian temporal paradox, Pichon attempts to reconstruct

Caraxs singularity around the idea of the dj-vu as reflective deception.

Caraxs films engage in a double system of references: on one side they

rework the history of cinema, and on the other they keep referencing each

other, producing a distortion right at the origin, undermining the very idea

of beginning and unsettling the notion of originality.

According to Pichon, in Caraxs films one witnesses then the

emergence of a distorted intimacy, one that is always redoubled and

permanently missed, constantly transfigured into the illusory. The romantic

pessimism that invests Caraxs works can then be traced to the problematic

nature of every encounter, which is submitted, to say it with Blanchot, to the

logic of the always, but not yet (Blanchot, 1997, p.37). While it is true that

his movies always revolve around a couple, it must be added that this is

constantly opened up by the presence of a third, or finds itself fragmented

through the intervention of foreign elements. The couple, emblem of

ambiguity, becomes then the key figure of this analysis: the love relation,

which aspires to be fully original and absolute, is always disturbed, weighed

down by memories or consumed in anticipations and coincidences (there is

always a potential other partner, in the past Les Amants du Pont-Neuf or

in a life yet to be discovered Pola X) becoming part of a series of shifts

Film-Philosophy 16.1 (2012)

Film-Philosophy ISSN 1466-4615 245

from which it can never seal itself off. The two is never a fully formed

outline; rather it is always committed since the beginning to a complex

series of references and remainders, which end up breaking it apart. The

exhaustion of language always at work in the couple, a proper fall into

silence (Alex in Mauvais Sang is ironically called langue pendu

chatterbox because of his proverbial silences), indicates of this relentless

interruption, but it also prefigures the constant possibility for something

extra-ordinary to happen, for a transfiguration of the present beyond

recognition. This also helps understanding how Caraxs interest in silent

cinema goes beyond a mere referential game, participating instead of the

very nucleus of his cinematic intention. Always lingering on the absurd, his

films proceed according to the impossible. In Caraxs own words we are

bound to the impossible.

Crafted around a number of philosophical digressions (Bergson, but

also Deleuze, most notably in Pichons insistence on difference and

repetition) and animated through a series of comparative studies (Carax and

Godard, Rivette, Garrel) the book is at times willfully repetitive, though the

author never falls into the anecdote. Pichon illustrates his ideas with a

wealth of examples, showing not only impressive knowledge of the subject

matter, but a profound ability to read the image.

The main problem seems to lay in the approach to the most

problematic philosophical points. When Pichon for example briefly

introduces the expression deconstruction of singularity, moving into the

complex Derridean territory, the author stops before his intuition could be

done justice to and, as a consequence of this, the discussion remains

hanging. There where a productive path could open up the analysis to an

even richer level, the philosophical and the filmic elements remain instead

foreign to one another.

Beside scholarly rigor and detailed analysis, the greatest merit of the

book is that of allowing the emotional intelligence and visual inventiveness

of Caraxs filmmaking to emerge. Pichon offers a significant contribution to

the understanding of one of the most interesting personalities of

contemporary cinema. Furthermore it provides a useful tool for those

interested in framing Caraxs work within a wider horizon, that of a cinema

that keeps interrogating its own nature and its place between the real and the

imaginary.

You might also like

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- CLDH Enforced Disappearance EN 2008Document49 pagesCLDH Enforced Disappearance EN 2008paguro82No ratings yet

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- War As A SubjectDocument7 pagesWar As A Subjectpaguro82No ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5795)

- Political I Lam After The Ara Pring: Sign inDocument11 pagesPolitical I Lam After The Ara Pring: Sign inpaguro82No ratings yet

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- War of The Camps REX BOULDERDocument6 pagesWar of The Camps REX BOULDERpaguro82No ratings yet

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- CUP123 01rugo FF PDFDocument16 pagesCUP123 01rugo FF PDFpaguro82No ratings yet

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Film ListDocument3 pagesFilm Listpaguro82No ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Daniele Rugo: Contrapuntal Close-Up: The Cinema of John Cassavetes and The Agitation of SenseDocument16 pagesDaniele Rugo: Contrapuntal Close-Up: The Cinema of John Cassavetes and The Agitation of Sensepaguro82No ratings yet

- Rugo Requiem PDFDocument16 pagesRugo Requiem PDFpaguro82No ratings yet

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Norris CavellDocument18 pagesNorris Cavellpaguro82No ratings yet

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Visions and Revisions: Hollywood's Alternative Worlds: David SterrittDocument8 pagesVisions and Revisions: Hollywood's Alternative Worlds: David Sterrittpaguro82No ratings yet

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Jack Hazan InterviewDocument2 pagesJack Hazan Interviewpaguro82No ratings yet

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Interview With Flipside's Sam DunnDocument4 pagesInterview With Flipside's Sam Dunnpaguro82No ratings yet

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- One+One: and The London Underground Film Festival Present "Revolutions in Progress" Screening and DiscussionDocument2 pagesOne+One: and The London Underground Film Festival Present "Revolutions in Progress" Screening and Discussionpaguro82No ratings yet

- HE Uture of Edagogy: THE Oncept and The DisasterDocument3 pagesHE Uture of Edagogy: THE Oncept and The Disasterpaguro82No ratings yet

- Nightbirds - Andy Milligan. An InterviewDocument3 pagesNightbirds - Andy Milligan. An Interviewpaguro82No ratings yet

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Comparatives and SuperlativesDocument4 pagesComparatives and SuperlativesMaguis RomaniNo ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- English Grammar-B1Document19 pagesEnglish Grammar-B1claudia r.No ratings yet

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- This Is Amazing Grace by Phil WickhamDocument3 pagesThis Is Amazing Grace by Phil WickhamArmen MovsesyanNo ratings yet

- Nota English Upsr PDFDocument13 pagesNota English Upsr PDFNur QalbiNo ratings yet

- Yelawolf - Radioactive (Deluxe Edition)Document21 pagesYelawolf - Radioactive (Deluxe Edition)claudiuNo ratings yet

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- ALAN TURNEY A Feeling of Beauty - Natsume Soseki's IchiyaDocument5 pagesALAN TURNEY A Feeling of Beauty - Natsume Soseki's IchiyaIrene BassiniNo ratings yet

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1091)

- Avoiding Muddy ColorDocument1 pageAvoiding Muddy ColoraylinaraNo ratings yet

- Panda Bear Amigurumi Crochet Pattern - Free! - Angie's Art StudioDocument9 pagesPanda Bear Amigurumi Crochet Pattern - Free! - Angie's Art StudioKatherine Hernandez Espinoza100% (1)

- Growlithe PatternDocument13 pagesGrowlithe PatternCarlotta Belotti100% (2)

- Power Point Past SimpleDocument31 pagesPower Point Past Simpleduvan92No ratings yet

- PedagodieDocument5 pagesPedagodiegabib97No ratings yet

- ALP Vocab Test 4Document2 pagesALP Vocab Test 4Jivko DimitrovNo ratings yet

- Siems Resume - April 2015Document1 pageSiems Resume - April 2015api-268277273No ratings yet

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Technical Definition MorphemesDocument2 pagesTechnical Definition Morphemesapi-355877838No ratings yet

- Beadwork QuickEasy Feb 2011-1. 48Document48 pagesBeadwork QuickEasy Feb 2011-1. 48li-C.94% (16)

- Paralysis and EpiphanyDocument4 pagesParalysis and EpiphanyCristiane Slugovieski100% (3)

- Stippling TutorialDocument9 pagesStippling TutorialTrandescentNo ratings yet

- ChristianDocument13 pagesChristianJesuoah GerunggayNo ratings yet

- Big Hello Kitty enDocument15 pagesBig Hello Kitty enBilystone100% (2)

- Spanish Unit 23Document4 pagesSpanish Unit 23Oriol CobachoNo ratings yet

- Cradle of Minoan and Mycenaean ArtDocument6 pagesCradle of Minoan and Mycenaean ArtNeraNo ratings yet

- Sakura - Ikimono Gakari LyricsDocument1 pageSakura - Ikimono Gakari Lyricsyvonne chanNo ratings yet

- Fries - The Expression of The FutureDocument10 pagesFries - The Expression of The FuturedharmavidNo ratings yet

- Ode To A NightingaleDocument6 pagesOde To A Nightingalescribdguru2No ratings yet

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Every Little StepDocument3 pagesEvery Little StepAlan Santoyo LapinelNo ratings yet

- Form PacketDocument9 pagesForm Packetapi-296021053No ratings yet

- Narrated Monologue - Dorrit CohnDocument17 pagesNarrated Monologue - Dorrit CohnLucho Cajiga0% (1)

- Does God Help His Own?Document59 pagesDoes God Help His Own?Δαμοκλῆς Στέφανος100% (10)

- Comparatives and SuperlativesDocument12 pagesComparatives and SuperlativesiloveleeminhoNo ratings yet

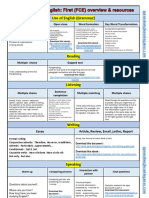

- FCE at A Glance (Overview + Resources) TableDocument1 pageFCE at A Glance (Overview + Resources) Tableanestesista0% (1)

- The Stoic Mindset: Living the Ten Principles of StoicismFrom EverandThe Stoic Mindset: Living the Ten Principles of StoicismRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (12)

- The Story of Philosophy: The Lives and Opinions of the Greater PhilosophersFrom EverandThe Story of Philosophy: The Lives and Opinions of the Greater PhilosophersNo ratings yet