Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Court Says Police Can Install Cameras On Your Property Without A Warrent If It Is A Field PDF

Court Says Police Can Install Cameras On Your Property Without A Warrent If It Is A Field PDF

Uploaded by

kidsarentcomoditiesOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Court Says Police Can Install Cameras On Your Property Without A Warrent If It Is A Field PDF

Court Says Police Can Install Cameras On Your Property Without A Warrent If It Is A Field PDF

Uploaded by

kidsarentcomoditiesCopyright:

Available Formats

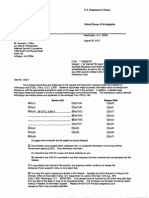

An attempt to thwart the 4th Amendment of

the United States Constitution in order to

cave to the whims of federal drug agents

has led to this:

Court Says Police Can

Install Cameras On Your

Property Without Warrant

If Your Property Is A

'Field',

Soon enough, 'field' will be redefined to

include anything with a single weed

growing in it.

Privacy

by Timothy Geigner

Wed, Oct 31st 2012 12:48pm

Filed Under:

4th amendment,privacy,surveillance

from the because-that-won't-be-abused dept

We just heard some good news about the protection of the 4th

Amendment with regards to cell phone data. i However, we've

also learned that some law enforcement officials apparently

find getting warrants to read our email to be incredibly

annoying. These LEOs shouldn't fret too much as they now have

some good news of their own -- they apparently don't need a

warrant to turn your property into a movie set if your

property resembles an open field.

That's the ruling from Green Bay, Wisconsin, where the fight

against the world's mildest drug (marijuana) is

apparently worth twisting the 4th Amendment into a giant

pretzel.

U.S. District Dumbass William Griesbach ruled that it was

reasonable for Drug Enforcement Administration agents to

enter rural property without permission -- and without a

warrant -- to install multiple "covert digital surveillance

cameras" in hopes of uncovering evidence that 30 to 40

marijuana plants were being grown.

This is in response to the two defendants in the case seeking

to have footage from said surveillance cameras thrown out in

their court case on unreasonable search and seizure grounds.

Judge Griesbach made this ruling on the recommendation of US

Magistrate William Callahan, who based his position on a US

Supreme Court Case ruling that open fields were not covered

under the 4th Amendment and didn't require a warrant. Perhaps

ironically, this ruling was made in 1984, a time when the

prevalence and sophistication of such surveillance equipment

wasn't what it is today.

Still, I'm struck by two problems in this ruling (and the

previous Supreme Court ruling as well). First, the two

defendants in this case had fences and signs up around their

property that said "No Trespassing", so I'm not sure if the

definition of "open field" fully applies here. Secondly, even

if you argued that it did apply, how is this exception to the

4th Amendment not completely throwing the door wide open for

abuse? What, after all, constitutes an "open field"? Is there

a certain acreage criteria that needs to be met? A certain

number of trees or shrubberies? Rabbit hole count?

And this doorway to abuse has been opened all because police

didn't want to bother to get a search warrant to put video

equipment on private property.

Judge Protects Cellphone Data On 4th

Amendment Grounds, Cites Government's

Technological Ignorance

i

from the they're-RIGHTS,-not-INCONVENIENCES dept

Various US government agencies have spent a lot of time

and energy hoping to ensnare as much cell phone data as

possible without having to deal with the "barriers"

erected by the Fourth Amendment. The feds, along with Los

Angeles law enforcement agencies, Hhave bypassedH the

protections of the Fourth Amendment by deploying roving

cell phone trackers that mimic mobile phone towers. The

FISA Amendments Act has been used as a "blank check" for

wholesale spying on Americans and has been abused often

enough that the Director of National Intelligence

was Hforced to admitH these Fourth Amendment violations

publicly.

The good news is that a few of these overreaches are

receiving judicial pushback. Orin Kerr at the Volokh

Conspiracy Hhas a very brief writeup of a recent shutdown

of another cellphone-related fishing expedition led by an

assistant US Attorney.HAn attempt was made to acquire

records for ALL cell phones utilizing four different

towers in the area of a specific crime at the time of the

event. As Kerr notes, this ruling refers to the Fifth

Circuit court decision that found cell phone data to be

protected under the Fourth Amendment, thus Hrequiring a

warrantH to access it.

Magistrate Judge Smith points out that part of the issue

is that the principals involved (the assistant US Attorney

and a special agent) seemed to lack essential knowledge of

the underlying technology, and that this lack of knowledge

prevented them from recognizing the overreach of their

request:

Moreover, it is problematic that neither the assistant

United States Attorney nor the special agent truly

understood the technology involved in the requested

applications. See In re the Application of the U.S. for an

Order Authorizing the Installation and Use of a Pen

Register and Trap and Trace Device, F.Supp.2d ,

2012 WL 2120492, at *2 (S.D. Tex. June 2, 2012). Without

such an understanding, they cannot appreciate the

constitutional implications of their requests. They are

essentially asking for a warrant in support of a very

broad and invasive search affecting likely hundreds of

individuals in violation of the Fourth Amendment.

There has been a Hlot of discussionH here at Techdirt

regarding the incredible Hlack of knowledgeH present in

those seeking to regulate or exploit various technologies.

Considering the amount of possible collateral damage and

the heightened chance of rights violations, you'd think

these entities would be exercising maximum caution before

tampering with something they don't understand. Instead,

the common approach is to use the ends (safety, crime

prevention, etc.) to justify the missteps and rightstrampling of the means, leaving the judicial system and

various trampled citizens to sort out the mess.

Judge Smith quotes the Fourth Amendment and points out

that warrants must be issued and only "upon probable

cause" before continuing to run down the list of wrongs in

this request.

Finally, there is no discussion about what the Government

intends to do with all of the data related to innocent

people who are not the target of the criminal

investigation. In one criminal investigation, the

Government received the names, cell phone numbers, and

subscriber information of 179 innocent individuals. See

United States v. Soto, No. 3:09CR200 (D.Conn. May 18,

2010) (Memorandum in Support of Motion to Suppress).

Although the use of a court-sanctioned cell tower dump

invariably leads to such information being provided to the

Government, in order to receive such data, the Government

at a minimum should have a protocol to address how to

handle this sensitive private information.

But, as Smith points out, the government doesn't have a

protocol in place, even more than two years down the road.

Although this issue was raised at the hearing, the

Government has not addressed it to date.

This is hardly new territory for government agencies. The

TSA has had Hnearly 20 monthsH to begin taking public

comments on the use of various body imaging scanners, but

despite two trips to the DC Circuit Court, it has yet to

begin this process, something generally

undertaken before implenting a new system. If it's

something the government feels may be unpopular with the

public, it tends to attempt to stall indefinitely, an

(in)action that (again) places the burden back on the

courts and the general public.

But, at least in this case, Judge Smith is using this lack

of action against the government representatives.

This failure to address the privacy rights for the Fourth

Amendment concerns of these innocent subscribers whose

information will be compromised as a request of the cell

tower dump is another factor warranting the denial of the

application.

It's a good sign that stalling tactics may hurt more than

help in the future. Many government and law enforcement

agencies are still looking for any loophole in current

laws in order to bypass the limitations placed on them by

the Constitution. There's still a long way to go before

there's anything resembling an equitable relationship

between the general public and those in power, but we'll

take everything we can get and (hopefully) receive more

help pushing back against these intrusions.

In re U.S. ex rel. Order Pursuant to 18 U.S.C. Section 2703(d), Slip Copy (2012)

2012 WL 4717778

Only the Westlaw citation is currently available.

United States District Court,

S.D. Texas,

Corpus Christi Division.

In the Matter of the Application of the UNITED

STATES of America for an ORDER PURSUANT

TO 18 U.S.C. 2703(D) Directing Providers to

Provide Historical Cell Site Locations Records.

C.R. Nos. C12670M, C12671M, C

12672M, C12673M. | Sept. 26, 2012.

Opinion

ORDER DENYING THE GOVERNMENT'S

REQUESTS FOR CELL TOWER DUMPS

had difficulties discussing or explaining the technology to be

used.

The Government's attorney also explained that there was a

special agent in Dallas who serves as a Government expert

regarding these matters. This expert would review all of the

data obtained and provide guidance as to what direction the

investigation of the subject should take. Specifically, after

analyzing the raw data, he would determine a number of

cell phones to target in the investigation. The data obtained

would not only show all of the cell phones that were in the

vicinity of the crime scene, but likely would demonstrate the

direction the calls were hitting the cell tower, which in turn

would enable the Government to triangulate the path of the

cell phone's journey. The assistant United States Attorney

could not explain much more about the expert, his role, or

his insights into the electronic surveillance. However, he did

acknowledge that there would in all likelihood be a substantial

amount of data produced pursuant to the requested court

order.

BRIAN L. OWSLEY, United States Magistrate Judge.

ANALYSIS

*1 These four matters come before the Court pursuant to a

written and sworn application pursuant to 18 U.S.C. 2703(d)

by an assistant United States Attorney who is an attorney

for the Government as defined by Rule 1(b)(1)(B) of the

Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure. Specifically, these four

applications seek an Order directing that all historical cell

site records from four separate telecommunications providers

for specific towers be disclosed to the Government. Each

application is the same except for seeking data from different

providers regarding different cell towers.

BACKGROUND

In an ex parte hearing on July 3, 2012, the assistant United

States Attorney acknowledged that the Government was

seeking a cell tower dump in each of the four applications.

Specifically, he sought all telephone numbers and all other

subscriber information for the hour before and the hour after

the crime being investigated. The victim of the crime had a

cell phone that was taken by the subject of the investigation

when he left the crime scene. Moreover, it is believed that the

subject of the investigation also has a cell phone.

When discussing the technology with the assistant United

States Attorney, it became apparent that he did not understand

it well. Similarly, the special agent present at the hearing

The Government relies on 2703 in its request for approval

of its cell tower dump requests. That statute does not address

cell tower dumps. Instead, pursuant to 2703, Congress has

authorized the Government to obtain customer records from

telecommunications providers

A governmental entity may require a provider of electronic

communication service or remote computing service to

disclose a record or other information pertaining to a

subscriber to or customer of such service (not including the

contents of communications) only when the governmental

entity

(A) obtains a warrant issued using the procedures described

in the Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure (or, in the case

of a State court, issued using State warrant procedures) by

a court of competent jurisdiction;

*2 (B) obtains a court order for such disclosure under

subsection (d) of this section;

(C) has the consent of the subscriber or customer to such

disclosure;

(D) submits a formal written request relevant to a law

enforcement investigation concerning telemarketing fraud

for the name, address, and place of business of a subscriber

2012 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works.

In re U.S. ex rel. Order Pursuant to 18 U.S.C. Section 2703(d), Slip Copy (2012)

or customer of such provider, which subscriber or customer

is engaged in telemarketing ...; or

(E) seeks information under paragraph (2).

18 U.S.C. 2703(c)(1). The subscriber or customer

information may include the person's name, address;

telephone call records, including times and durations;

lengths and types of services; subscriber number or

identity; and means and source of payment. 18 U.S.C.

2703(c)(2). Obtaining a court order, is simply a matter

of a law enforcement officer providing the court with

specific and articulable facts showing that there are

reasonable grounds to believe that the contents of a wire or

electronic communication, or the records or other information

sought, are relevant and material to an ongoing criminal

information. 18 U.S.C. 2703(d) (emphases added).

Regarding the specific and articulable facts standard, some

courts have rejected arguments that probable cause and the

Fourth Amendment must be applied to requests for historical

cell site data. See United States v. Graham, 846 F.Supp.2d

384, 2012 WL 691531, at *1618 (D.Md. Mar. 1, 2012);

United States v. Benford, No. 2:09CR86, 2010 WL 1266507,

at *23 (N.D.Ind. Mar. 26, 2010) (unpublished); see also

In re Applications of United States for Orders Pursuant To

Title 18, U.S.Code Section 2703(d), 509 F.Supp.2d 76, 80

81 (D.Mass.2007) (reversing Applications of United States

for Orders Pursuant To Title 18, U.S.Code Section 2703(d)

to Disclose Subscriber Information and Historical Cell Site

Information, 509 F.Supp.2d 64 (D.Mass.2007) in which a

magistrate judge held that probable cause was required for

the disclosure of historical cell site information). Other courts

have determined that probable cause is necessary for such

information. See In the Application of the United States for

an Order Authorizing The Release of Historical CellSite

Information, 809 F.Supp.2d 113, 11820 (E.D.N.Y.2011);

In the Application of the United States for Historical Cell

Site Data, 747 F.Supp.2d. 827, 83740 (S.D.Tex.2010); In re

Application of United States For an Order Authorizing the

Release of Historical CellSite Information, 736 F.Supp.2d

578, 579 (E.D.N.Y.2010); In the Application of the United

States of America For and [sic] Order: (1) Authorizing the

Use of a Pen Register and Trap and Trace Device; (2)

Authorizing Release of Subscriber and Other Information;

and (3) Authorizing the Disclosure of LocationBased

Services, 727 F.Supp.2d 571, 58384 (W.D.Tex.2010); In re

Application of United States For an Order Pursuant to 18

U.S.C. 2703(d), Nos. C12755M, C12756M, C12

757M, 2012 WL 3260215, at *2 (S.D.Tex. July 30, 2012)

(unpublished). In discussing the appropriate standard, the

Eastern District of New York explained that a request for cell

site information raises a greater concern than a request for a

tracking device on a vehicle

*3 The cell-site-location records at

issue here currently enable the tracking

of the vast majority of Americans.

Thus, the collection of cell-sitelocation records effectively enables

mass or wholesale electronic

surveillance, and raises greater Fourth

Amendment concerns than a single

electronically surveilled car trip. This

further supports the court's conclusion

that cell-phone users maintain a

reasonable expectation of privacy in

long-term cell-site-location records

and that the Government's obtaining

these records constitutes a Fourth

Amendment search.

In the Application of the United States for an Order

Authorizing The Release of Historical CellSite Information,

809 F.Supp.2d at 11920. Similarly, the Western District of

Texas has explained that it will insist on strict adherence

to the requirements of Rule 41 on all requests for CSLI,

including requests for historical data. The warrants will be

granted only on a showing of probable cause.... In the

Application of the United States of America For and [sic]

Order: (1) Authorizing the Use of a Pen Register and Trap

and Trace Device; (2) Authorizing Release of Subscriber and

Other Information; and (3) Authorizing the Disclosure of

LocationBased Services, 727 F.Supp.2d at 58384.

This Court has concluded that given refinements in location

technology regarding cell site information that access to such

data enables that person to plot with great precision where

the cell phone user has been during a given time period.

In the Application of the United States for Historical Cell

Site Data, 747 F.Supp.2d. at 83537. Consequently, cell site

data are protected pursuant to the Fourth Amendment from

warrantless searches. Id. at 83840. Thus, the Government

could obtain the cell site data only by establishing probable

cause pursuant to Rule 41 of the Federal Rules of Criminal

Procedure. On appeal pursuant to 28 U .S.C. 636, the

Court overruled the Government's objections explaining

that [w]hen the government requests records from cellular

services, data disclosing the location of the telephone at

the time of particular calls may be acquired only by a

2012 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works.

In re U.S. ex rel. Order Pursuant to 18 U.S.C. Section 2703(d), Slip Copy (2012)

warrant issued on probable cause. In the Applications of

the United States for Historical Cell Site Data, Misc. No.

H11223 (S.D.Tex. Nov. 11, 2011) (Order on Objections)

(unpublished) (citing U.S. Const. amend 4). Moreover,

because the requested records would show the date, time,

called number, and location of when the call was made,

this information was constitutionally protected from this

intrusion. Id. Finally, the Court determined that [t]he

standard under the Stored Communications Act, 18 U.S.C.

2703(d), is below that required by the Constitution. Id.

Here, the assistant United States Attorney simply relied on an

application based on specific and articulable facts standard.

He has not submitted an affidavit pursuant to Rule 41 of the

Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure demonstrating probable

cause supporting the request for the records. This Court has

concluded that such requests must be made based on the

probable cause standard.

*4 Moreover, it is problematic that neither the assistant

United States Attorney nor the special agent truly understood

the technology involved in the requested applications. See

In re the Application of the U.S. for an Order Authorizing

the Installation and Use of a Pen Register and Trap and

Trace Device, F.Supp.2d , 2012 WL 2120492, at

*2 (S.D. Tex. June 2, 2012). Without such an understanding,

they cannot appreciate the constitutional implications of

their requests. They are essentially asking for a warrant

in support of a very broad and invasive search affecting

likely hundreds of individuals in violation of the Fourth

Amendment. The Constitution mandates that [t]he right of

the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and

effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures. U.S.

End of Document

Const. amend IV. It further provides that no Warrants shall

issue, but upon probable cause. Id.; see also Fed.R.Crim.P.

41 (addressing the issuance of warrants). There is nothing

from the Government in its four applications to support the

position that the specific and articulable facts standard and

2703(d) apply to cell tower dumps.

Finally, there is no discussion about what the Government

intends to do with all of the data related to innocent people

who are not the target of the criminal investigation. In

one criminal investigation, the Government received the

names, cell phone numbers, and subscriber information

of 179 innocent individuals. See United States v. Soto,

No. 3:09CR200 (D.Conn. May 18, 2010) (Memorandum

in Support of Motion to Suppress). Although the use of a

court-sanctioned cell tower dump invariably leads to such

information being provided to the Government, in order to

receive such data, the Government at a minimum should have

a protocol to address how to handle this sensitive private

information. Although this issue was raised at the hearing,

the Government has not addressed it to date. This failure

to address the privacy rights for the Fourth Amendment

concerns of these innocent subscribers whose information

will be compromised as a request of the cell tower dump is

another factor warranting the denial of the application.

CONCLUSION

Accordingly, the Government's four applications pursuant to

18 U.S.C. 2703(d) requesting historical cell site data are

denied without prejudice.

ORDERED.

2012 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works.

2012 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works.

You might also like

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (842)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5807)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1091)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (346)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- FBI Releases Zacarias Moussaoui Dossier PDFDocument67 pagesFBI Releases Zacarias Moussaoui Dossier PDFLoraMorrisonNo ratings yet

- Available Upon RequestDocument1 pageAvailable Upon RequestLoraMorrisonNo ratings yet

- H1N1 Clinics Staff E Mail 10 16 09 PDFDocument2 pagesH1N1 Clinics Staff E Mail 10 16 09 PDFLoraMorrisonNo ratings yet

- Court Rebuffs Government OvDocument2 pagesCourt Rebuffs Government OvLoraMorrisonNo ratings yet

- FtLyon Referral Sites MapDocument1 pageFtLyon Referral Sites MapLoraMorrisonNo ratings yet