Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Content Server

Content Server

Uploaded by

Karlo Reyes0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

4 views9 pagespedia journal

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this Documentpedia journal

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

4 views9 pagesContent Server

Content Server

Uploaded by

Karlo Reyespedia journal

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 9

EAPERENCE INPEDIATAIG EDUCATION AND PRACTICE Ambulatory Child Health (2001) 7: 43-51

Environmental illness: educational needs of

pediatric care providers

Alan Woolf'** and Sabrina Cimino**

‘Department of Pediatrics, Harvard Medical School, “Pediatric Environmental Health Center, Division of General

Pediatrics, Children’s Hospital and °Regional Poison Control & Prevention Center Serving Massachusetts &

Rhode Island, Boston, MA, USA

ABSTRACT

Background

Objective

Methods

Results

Conclusion

Implications for

practice

Assessing the impact of children's exposures to environmental toxins is an

emerging new subspecially in cinical pediatrics. However, pediatric health

professionals in practice may not be familiar wit critical information

necessary to diagnose and manage environmental toxic exposures in

children,

The objective of this study was to investigate the perceptions of

pediatrcians, nurses, and nurse practitioners regercing their own practices

and educational needs concerning pediatric environmental exposures.

Health professionals attending a general pediatric postgraduate course were

administered @ 22-tem questionnaire on ther practices and educational

needs in children’s enviconmental health.

A total of 93% of participants returned usable questionnaires. Within the

previous 6 months, over 90% of pediatricians and nurse practitioners had

Giagnosed food possoning: almost 50% had diagnosed lead poisoning; 50%

had diagnosed a child's illness as due to exposure to a toxic chemical; and

24% had diagnosed ‘building-related illness.” Although 90% of pediatricians

and 82% of nurses and nutse practitioners stated that they routinely asked

families about parental occupations, only 35% of both groups asked about

parental hobbies. Only 58% of the groups asked about smoke detectors in

the home, and only 18% of nurses and 9% of pediatricians queried families

about their use of radon detectors. Over 70% of all three groups indicated a

high intrest level in the folowing postgraduate educational tops: taking in

environmental history, breast mik contaminants, food allergies, food

Contarination, and illness related to tobacco smoke, Topics that did not

garner as high an intrest level included: ctildhood lead poisoning, radon

poisoning, and building-related iliness.

Pediatric health professionals commonly diagnose environment-elated

illnesses, and they include such topics during well child care, They indicale

a variety of educational needs concerning pediatic environmental health

issues.

Health care professionals are increasingly asked by parents to include

environmental toxins among the possible causes of a child’ il health. Our

‘The research was presonted tte annul meeting ofthe Ambulatory Pedic Asseclaton on May, 1999, n San Francisco, Caltoria|

(© 2001 Bleckwet Science Lis

44 A Woolf and § Cimino

PERIENCE IN PEDIATRIC EDUCATION AND PRACTICE

results suggest that clinicians recognize their own need for futher training in

the principles of pediatric environmental health Further research is needed

in determining which modalties are best suited to achieve such educational

objectives

Keywords

Introduction

The impact of environmental

toxins on children's health is

of growing concem around

the world. Almost 25% of

‘Americans live near one of

the more than 1400 Super-

Parental concems about children’s

exposures to contaminants in foods

and breast milk, the effects of hormone-

environmental bealth, environmental toxicology. pediatrio, postgraduate education, toxicology

exposures to contaminants in foods and breast milk,

the effects of hormone-like chemicals on growth and

development, natural carcinogens such as radon, the

ubiquity of air and water pol

lutants, and other environ-

imental threats to children's

health are growing. Building-

related illness, irrtant-type

symptoms caused by poor

fund sites (abandoned toxic ‘lke chemicals on growth and develop- indoor air quality, is more

waste dumps slated for | ment, nalural carcinogens such as often being used in conjunc

cleanup by the US gov- fadon, and other environmental threats tion with children and is a

emment), with 12.5 milion tochildren’s health are growing. source of parental concer

people (including 3-4 milion

children) living within + mile

cof a toxie waste dump.'? The prevalence of childhood

asthma increased steadily in London, UK, between

1978 and 1991.° There is good evidence that in part

this increasing prevalence is related to and exacer-

bated by increasing amounts of indoor and outdoor

air polutants.*® Athough the incidence of lead poison-

ing has decreased in the United States, more than

940000 children stil have blood lead levels greater

than 10ygidL, with disproportionately more minority

and inner-city children living in poverty affected.®

The prevalence of respiratory conditions was higher

among second- and fith-grade schoolchildren grow

ing up in highly polluted Israeli neighbourhoods.” An

investigation into the contamination of indoor air by

molds in Stockholm, Sweden, showed a correlation

between fungi in dust samples and the sensitization

cf atopic children.’ An epidemiological study. in

Germany, England, Canada, and Sweden quantified

aan excessive risk of lung cancer related to high levels,

‘of domestic indoor radon concentrations?

The scope of pediatric environmental illness broadly

tefers to those elements in the environment, such

as allergens, man-made or natural chemicals, gases,

radiation, food or water contaminants, and other

toxins, that have the potential to adversely impact on a

child's health. Parental concems about children’s

about schools and day care

centres.

Yet these environmental toxins receive scant atten-

tion in medical or nursing school, and many health

providers have limited knowledge of how to properly

assess the role of such toxins in a childs illness. In

this regard, recent review articles on pediatric envi-

ronmental health have begun to address issues of

importance for health care providers.'™"" The Envi-

ronmental Protection Agency (EPA) is devoting more

resources to the study of how environmental contam-

inants may adversely affect the health of children

Many professional organizations, including the Cri

dren's Environmental Health Network, have already

started to address research needs with regard to

assessing the child with environmentally related

illness. The American Academy of Pediatrics

has recently published a manual to address the

gaps in pediatricians’ knowledge in the environmen-

tal health problems of children, a testament to the

growing importance ofthis emerging field of pediatric,

medicine."

In this study the current practices and educational

needs of pediatricians, nurses, and nurse practition-

ers in office practice were surveyed. The purpose of

the investigation was to uncover the perceptions of

pediatricians, nurses, and nurse practitioners regard-

heel Sclnce Lc, Ambulatory Chil Heath 71). 49-51

EXPERENG

EIN PEDIATAIC EDUCATION AND PRACTICE

ing their own practices and educational needs con-

cerning pediatric environmental toxic exposures and

their diagnosis and management.

Methods

A cross-sectional survey of health professionals’

experience and perceived educational needs con-

ceming pediatric environmental health was prepared

(see Appendix). The survey was given to a conve-

rience sample drawn from health professionals who

were already interested in pursuing continued medical

education. Participants in ‘Advances in Pediatric

Health Care’, a general pediatrics (no environmental

health topics) postgraduate course offered by Chil-

dren's Hospital, Boston in April 1998, were asked to

fill outa brief, forced choice 22-item questionnaire that

had previously been informally piloted. Participants

were asked about environmental health topics they

routinely include in conversations with parents during

a well child care visit. They were asked if they had

made specific environmentally related diagnoses

within the past 6 months (RSV bronchiolitis, iron defi-

cienoy anemia, and contact dermatitis were included

as high-frequency indicator diagnoses for compari-

son). Finally, participants were asked which topics in

pediatric environmental health to include in future

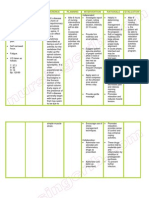

Table 1: Characteristics of survey respondents

Practitioners knowledge of environmental heath 45

postgraduate course offerings. Information on the

respondents’ age, gender, year of graduation, profes-

sional degrees, years in practice, and current patient

volume was also collected. Data were analysed

descriptively: comparisons were also made between

professional groups using the chi-square statistic and

Fishers’ exact test for smaller sample sizes. All analy-

ses were performed using SAS for the PowerMac

software;'* and o. was set at 0.05 for the demonstra-

tion of statistical significance

Results

As stated in the methods section, the data represent

responses from a convenience sample of health pro-

fessionals who were already interested in continued

medical education. Of the 217 course participants,

201 health care providers returned usable question-

naires: pediatricians (n = 121), pediatric nurse prac-

titioners (n = 36), nurses (n= 41) and three ‘other’

health professionals, for a response rate of 93%

Demographic details of the respondents are shown

in Table 1. Of the 121 pediatricians, two-thirds

were 41 years or older, and two-thirds of the sample

had been in practice for at least 11 years. These

pediatricians had an active practice: almost 80%

were ministering to more than 30 patients weekly

Practitioners Pediatricians Nurses RN

n 124 4a 36

‘Age range (years)

26-30 33% 9.8% 91%

31-40 29.8% 24.4% 30.3%

41-50 33.9% 39.0% 39.4%

260 33.0% 26.8% 21.2%

‘Years in professional practice

IV. Food contamination

A. Food-borne iliness

B. Breast mik contaminants

C. Food allergies

D. Pesticide contaminants of foods

VV. Indoor air pollution and children's health

A. Environmental tobacco smoke

B. Dust mites, allergens, and chitdhood asthma

C. Damp housing, molds, and childhood respiratory

disease

Respirable particulate contaminants

Volatile organic compounds

Indoor use of pesticides

Carbon monoxide, ritrogen oxides, and other

gases

H. Asbestos, formaldehyde, and building materials

|. Building-elated illness

Vi. Advocacy aspects of pediatric environmental health

AA, Regulatory authority and model legislation and

resolutions

B. Social cisparties and chidhood environmental

health

C. National and international searchable data

bases, Web sites, other resources in pediatric

environmental health

VIL. International aspects of pediatric environmental

health

Vill. Pediatric environmental health: a research agenda

ommo

kal Slence Lt, Ambulatory Chis Heath 71), 2-51

50 AWoolf and $ Cimino

EXPERIENCE IN PEDIATRIC EDUCATION AND PRACTIOE

regarding such environmental health topics as food-

associated illnesses, tobacco-related diseases, and

how to take a comprehensive pediatric environmental

history. Knowledge of community-based resources

and specialized referral centres in children's environ-

mental health can also help them to become more

proficient in the management ofthese patients.

References

1. US Environmental Protection Agency (1996) National

Protas list for hazardous waste sites: proposed rule.

Federal Register, 61: 67655-67682,

2 Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registy

(1998) Promoting Children's Health: Progress Report ofthe

Child Heath Workgroup, Board of Scientific Counselors.

US Department of Health and Human Services, Public

Health Service, Agency for Toxie Substances & Disease

Registry, Atanta, Georgia.

3. Anderson H R, Butland B K and Strachan D P (1994)

‘Trends in prevalence and severty of childhood asthma.

British Medical Journal, 308: 1600-1604

4 Smith K R, Samet J M, Romieu | and Bruce N (2000)

Indoor air pollution in developing countries and acute lower

respiratory infections in children. Thorax, 65: 518-532.

5 Jones A P (1998) Asthma and domestic air quality.

Society of Science Medicine, 47: 755-764

6 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (1997)

Update: blood lead levels. United States, 1991-94. Mor-

bidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 46: 141-146.

7 Goren A | and Helmann $ (1995) Respiratory cond-

tions among schoolchildren and their elationship to envi

ronmental tobacco smoke and other combustion products.

‘Archives of Environmental Health, 60: 112-18.

8 Wickman M, Gravesen S, Nordvall $ L, Pershagen G

‘and Sundell J (1992) Indoor viable dust-bound microfungi

in relation to residential characteristics, lving habits, and

‘symptoms in atopic and contol children. Journal of Allergy

and Clinical Immunology, 88: 752-758.

9 Jacobi W and Paretzke H G (1985) Risk assessment

{or indoor exposure to radon daughters, Science of the

Total Environment, 45: 551-562.

410. Balk S J (1996) The environmental history: asking the

right questions. Contemporary Pediatrics, 13: 19-36.

‘1 Lille D N (1995) Children and environmental toxins.

Primary Care, 22: 69-79.

12. Landtigan P J, Carison J E, Bearer C F, Crammer JS,

Bullard R D and Etzel R A (1998) Children's heath and the

environment: a new agenda for pediatric research. Envi=

ronmental Health Perspective Supplement, : 787-794,

13 Committee on Environmental Health American

Academy of Pediatrics (Eds RA Etzel and S J Balk) (1999)

Handbook of Pediatric Environmental Health. AAP, Ek

Grove Vilage, Iincs.

14. SAS Insitute Inc. (1985) SAS® User's Guide: Basic

Version (Sth edn). SAS Institute, Cary, NC.

18 Daaschner CW (1990) The division chief as a teacher

of adults. American Journal of Disease in Childhood, 144:

891-893,

46 Shannon M, Wool! Aand Goldman R (2000) Children's

‘environmental health: one year in a pediatric environmental

health clini. Journal of Toxicology ~Cinical Toxicology, 98:

559-560.

17 Roberts K B, DeWitt T G, Goldberg RL, Scheiner A P

(1994) A program to develop residents as teachers.

Archives of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine, 148,

405-410,

Biosketches

Dr Alan Woolf is the Director of the Program in Ci-

nical Toxicology at Children’s Hospital, Boston, the

Director of the Massachusetts/Rhode Island Poison

Control Center, the CoDirector of the Pediatric Envi-

ronmental Health Subspecialty Unit at Children's Hos-

pital, and an Associate Professor of Pediatrics at

Harvard Medical School, Boston.

Ms. Sabrina Cimino is a graduate of Tufts University

with a baccalaureate degree in Honors Biology. She

is currently a research associate in the Division of

General Pediatrics, Children’s Hospital, Boston.

Financial disclosure: The authors have no afiia-

tions with organizations with a financial interest in the

subject matter of this research. This work was sup-

ported in part by funds from the Comprehensive Envi-

ronmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act

(CERCLA) trust fund through a co-operative agree-

‘ment with the Agency for Toxic Substances & Disease

Registry, Public Health Service, US Deparment of

Health and Human Services.

Correspondence: Alan Woolf, MD, MPH, Regional

Poison Control Center, Children’s Hospital, IC Smith

Building, 300 Longwood Ave, Boston, MA 02115,

USA

Tel: (617) 3555187; Fax: (617) 7380032

© 2001 Blachwol Sionce Lid, Amauatory Child Health (1) 48-51

ATION AND P

ENCE IN PEDIATRIC Practitioners knowledge of environmental health 51

Appendix 1

Course needs assessment survey

How frequently do you ask at least one question about the following topics during a preschool well

child care visit:

‘Almost always Sometime Almost never

1. Parental tobacco use 1 2 i

2, Child's exposure to lead 1 2 3

3. Family's use of car seats i 2 3

4. Family's use of smoke detectors 1 2 3

5. Family's use of radon detectors 1 2 3

6. Parental occupation 1 2 3

7. Parental hobbies 1 2 3

How many patients have you seen in the past 6 months for whom you made a diagnosis of one of the

following health problems:

1, Lead poisoning 0 18 46 79 10-42 1345 >15

2. lron-deficiency anemia 0 13 46 79 10-42 1345 >15

3. Bronchiolitis 0 13 46 79 1042 1315 15

4, Sick building syndrome 0 13 46 79 1042 1315 15

5. Food-related allergy 0 13 46 7-9 1042 1845 >15

6. Exposure to toxie chemicals 0 13 46 79 1042 1845 >15

7. Contact dermatitis 0 1-3 46 79 1042 1845 >15

What is your interest level for each of the following topics for future CME education:

Low Moderate High

Chiidhood lead poisoning 1

Radon: diagnosis & management 1

Taking a pediatric environmental history 1

Sick school syndrome 1

Childhood food allergies 1

Pesticides, food & children 1

Smoking and tobacco-related illness 1

Breast milk contaminants 1

DUO BORD

aaanaunaad

© 2001 lac

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5813)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1092)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (844)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (348)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Nursing Care Plan Pott's DiseaseDocument2 pagesNursing Care Plan Pott's Diseasederic95% (21)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- RLE - BUBBLESHE Assessment (Emotion)Document17 pagesRLE - BUBBLESHE Assessment (Emotion)Karlo ReyesNo ratings yet

- Homans' Sign Vascular Disease: Prepared By: Rachelle Ann R. Recio II-Nur7, RLE 1Document28 pagesHomans' Sign Vascular Disease: Prepared By: Rachelle Ann R. Recio II-Nur7, RLE 1Karlo ReyesNo ratings yet

- LOVEPATHOHPYDocument1 pageLOVEPATHOHPYKarlo ReyesNo ratings yet

- BibliopocDocument4 pagesBibliopocKarlo ReyesNo ratings yet

- Charry Lou NavarroDocument11 pagesCharry Lou NavarroKarlo ReyesNo ratings yet

- Family Nursing Care Plan1Document2 pagesFamily Nursing Care Plan1Karlo ReyesNo ratings yet

- Respi Modalities 2Document6 pagesRespi Modalities 2Karlo ReyesNo ratings yet

- Respiratory AssessmentDocument79 pagesRespiratory AssessmentKarlo ReyesNo ratings yet

- Ineffectve NCP PediaDocument1 pageIneffectve NCP PediaKarlo ReyesNo ratings yet

- Health Teaching - Complementary FoodDocument1 pageHealth Teaching - Complementary FoodKarlo ReyesNo ratings yet

- Final Food Meal Distribution PDFDocument2 pagesFinal Food Meal Distribution PDFKarlo ReyesNo ratings yet

- High Blood Pressure: Gestational DiabetesDocument2 pagesHigh Blood Pressure: Gestational DiabetesKarlo ReyesNo ratings yet

- Aristotle's Linear Model of CommunicationDocument2 pagesAristotle's Linear Model of CommunicationKarlo ReyesNo ratings yet

- NCP1Document2 pagesNCP1Karlo ReyesNo ratings yet

- Vital Signs & DrugsDocument4 pagesVital Signs & DrugsKarlo ReyesNo ratings yet