Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Engel - Introduction (History of Hungary-Realm o St. Stephen) PDF

Uploaded by

Milos Ivanovic0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

177 views9 pagesOriginal Title

engel- Introduction (History of Hungary-realm o St. Stephen).pdf

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

177 views9 pagesEngel - Introduction (History of Hungary-Realm o St. Stephen) PDF

Uploaded by

Milos IvanovicCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 9

Preface

This book was written for the non-Hungarian reader who wishes to

discover what happened in the Carpathian basin during the Middle

Ages. Ibis to be hoped that nobody living in that region who has strong

national feelings will find comfort in it. Each of the nations of the

region has its own vision of the past, incompatible with that of the

others, and it was my firm intention that none of these visions should

bbe represented in this volume.

Throughout this book are to be found topics which do not sit

‘comfortably with particular national perspectives on the past. Many

Slovakians do not like to read, for instance, that their country was once

merely part of Hungary. Similarly, many Romanians prefer not to be

reminded that in the Middle Ages Transylvania was a Hungarian prov

ince, for they would like to believe that it was in fact a Romanian

principality, only loosely attached to a foreign power. All Croatians

know well that Croatia as a kingdom was older than Hungary, but

‘many of them would prefer to forget that this kingdom was much

smaller than modern Croatia and that their modern capital, Zagreb,

lay in Hungary. As for Hungarians, they sill eling on to the fiction that

there has only ever been one Hungary: the one that was founded by St

Stephen in 1000 AD, and which still survives after a thousand years,

even if it happens to be much smaller now than it once was. They will

never accept the obvious fact that the republic of Hungary is not iden-

tical to the ancient kingdom of Hungary; that, as political entities,

these are as different as are Turkey and the Ottoman Empire.

‘A particular area of sensitivity where national feelings are concerned

is the use of personal names and place names. There are as many name

forms as there are languages in the region, but there is no rule to

determine which form is correct when the language of communication

is English. Kosice in modern Slovakia can be called Kassa, for it was,

after all, a town in Hungary; but it was also known as Kaschau, for at

that time it was inhabited by Germans, and also Cassovia, for this was

the Latinised name of the town, used in contemporary records. To

make things easier, and also for the convenience of the reader, the

modern names of localities, the names which can be found on a modern

map, have been used in this book. (References to other names can be

found in the index.) The only exceptions to this rule are recently

created names, use of which would have involved obvious anachro-

nisms. One should not refer to Budapest before 1873 when the three

Cities of Buda, Obuda and Pest were administratively united to form

the modern capital. Also inappropriate in this book would be Brat-

islava or Cluj-Napoca, since both names were created in recent times,

‘Most persons who appear in this book have also had different names

in the vernacular languages of the region, while bearing a Latinised

name in contemporary records. It is often impossible to say which of

these names is historically ‘correct’. Johannes de Hunyad may equally

be called Tancu de Hunedoara (Romanian) or Janos Hunyadi

(Hungarian), because he was born a Romanian, but became a

Hungarian nobleman and also regent of Hungary. The lords de Gara

were Hungarian lords and can be referred to as Garai (Hungarian); but

they had many Croatian subjects who probably called them Gorjanski

(Croatian). However, it would have been nonsensical to differentiate

herween Hungarian lords according to their ‘modern nationality’; nor

would it have been meaningful to use their Latinised names, for these

people were not Romans. They were or became Hungarians, so in each

‘case the name that has been accepted in Hungarian historiography has

been used in this book, apart from their Christian names, which are

always given in the English form,

In preparing the manuscript I have very much profited from the

comments of Jorg K. Hoensch (Saarbriicken), Martyn Rady (London),

Janos M. Bak, Enikd Csukovits, Zsuzsanna Hermann, Andras Kubinyi,

Istvan Tringli and Auila Zsoldos (Budapest). | am peculiarly indebted

to Tamas Pélosfalvi for the vast amount of work that he put into

preparing the rough English version of my Hungarian text; and to

Andrew Ayton, who expended no less effort going through the text

meticulously word by word, making many suggestions and reworking

the prose extensively, thereby shaping the text into its now readable

form. I am also grateful to Béla Nagy for drawing the maps. But, in the

first place, I am indebted to my wife for supporting me with infinite

patience while I was writing this book,

Pal Engel

Introduction

Hungary is now one of the smallest countries of Europe. This book,

however, is concerned with the medieval period, and here the name

“Hungary’ will refer to the former kingdom of Hungary, which (even

without the kingdom of Croatia which was once united with it) was

more than three times larger than the present-day republic, and also

somewhat larger than the combined area of Great Britain and Ireland.

Itextended over the whole of the Carpathian basin, including not only

present-day Slovakia, but also considerable parts of Romania, Ukraine,

Austria, Yugoslavia and Croatia. Although the kingdom of Hungary

ceased to exist as an independent country at the end of the Middle

Ages, politically it survived as an autonomous part of the Habsburg

Empire until the end of the First World War in 1918.

LANDSCAPE AND HISTORY

‘The medieval kingdom of Hungary was born in a geographically well-

defined region that is usually called the Carpathian basin. ‘This is the

drainage-area of the middle Danube valley, and is named after those

‘mountain ranges with 2000 metre peaks that border it to the north, the

east and the south. It is divided by the Danube into two parts of

‘unequal proportions, and its centre is surrounded by mountain ranges

of medium height. The region to the west of the Danube has been

called Transdanubia since the period of the Ottoman occupation when

the capital of the country was temporarily moved from Buda to Press-

burg, on the northern bank of the river. The climate here is

predominantly temperate, with a relatively heavy rainfall. This is a

fertile landscape with hills of modest elevation interrupted by valleys

and basins, and with the Balaton, the largest warm-water lake in

Europe, at its heart. There are also mountain ranges ~ the Mecsek i

the south-east, the Bakony and the Vértes north of the Balaton — but

none rises higher than 600 metres. The landscape east of the Danube

is profoundly different. The Great Hungarian Plain, which stretches

without a single hill fiom Budapest to Oradea in the east and Belgrade

hh, can be regarded as a kind of appendix to the Eurasian

steppe. The climate is rather mote exueme here, with hot, dry

summers, but the region is abundantly supplied with water by its main

river, the Tisea, and its ibutaries, which, before the nineteenth-

century regulation works, meandered across the Great Plain, These

rivers were lanked by marshlands, swamps and inundation forests, and

also by fertile pastures and meadows, offering favourable conditions

for fishing and livestock breeding. To the north, cast and south-east of

the Great Plain, in present-day Slovakia and Romania, there are moun

tain ranges that become progressively higher as one travels outwards

from the Plain. Th

with the exception of the valleys, they have never been propitious to

hhuman settlement. Consequently, until the late Middle Ages these

mountains were covered by forests and largely uninhabited, and coloni-

zation of them continued into the early modern period.

When, in the ninth century, the Hungarians emerged from the

obscurity of prehistoric times they were living as nomadic horsemen on

the steppe along the Black Sea. They spoke a language of Finno-tIgric

origin, but their culture in general resembled that of the Turkic

peoples of the steppe. In 895 they moved into the Carpathian basin

tunder the leadership of their pagan prince, Arpéd, Here they soon

became notorious through their plundering raids into Westen Europe

in the tenth century. But Hungary asa political unit can only be spoken,

of from the year 1000, when Stephen I, a descendant of Arpad and

later to be known as Saint Stephen, converted to Christianity and was

crowned king. The kingdom founded by him became one of the great

powers ofthe region and remained so for 500 years, until the sixteenth

century, when it was crushed by the expanding Ottoman Empire. 1526,

the year of the batle of Mohdcs, where King Louis It himself was

Killed, constitutes the traditional closing date of the history of medieval

Hungary. The central part of the kingdom, including Buda, the

capital, was soon overrun by the Turks and incorporated into their

‘empire. In the east, Transylvania became an autonomous principality

under Ottoman contol, while the rest of the kingdom, which was

defensible against the Turks, was to be governed by kings from the

Habsburg dynasty until 1918, The latter, who were at the same time

rulers of Austria and Bohemia and also Holy Roman Emperors, consis-

tently regarded Hungary as one of their hereditary dominions

Between 1683 and 1699 they finally expelled the Turks from Hungary,

annexing Transylvania in 1690, but the integrity of medieval Hungary

y were formerly extremely rich in minerals; but,

|

|

1

was only restored in 1867, when the Austro-Fiungarian monarchy was

founded. However, the end of the First World War brought about the

total dismemberment of this shorelived empire, and the ‘Treaties of

‘Trianon and Versailles alloted more than two thirds of the former

Kingdom of Hungary to the newly born national states of Czechoso

vakia, Ansria, Romania and Yugoslavia.

“The medieval history of Hungary can be divided into three periods.

The age of the rulers of Arpéa's dynasty (1000-1301), atleast during

the fist ewo centuries, sil recalls in some respects the barbarian kings

dloms of the Dark Ages. The thirteenth century, when Hungaty had to

face, if only for a moment, the invasion of Dzinghis Khan's successors

(1241, witnessed spectacular changes inthe structure of both society

and the economy. From this time on, by its outlook as well as by the

nature of its institutions, Hungary increasingly resembled dhe elder

Kingdoms of Christian Europe, although, lying on the pesiphery of

Christendom, it quite naturally preserved a number of features pec

lar to itself. The period of the Angevin rulers (1301-1382) and Kang

Sigismund of Luxembourg (1387-1437) can be deseribed as. the

apogee of medieval Hungary: It is marked by strong royal powes, an

aggressive foreign policy and, somewhat in contrast to the manifold

crisis that was then gripping the West, dynamic economic develop-

ment. ‘The main feature of the last century of medieval Hungasy

(1487-1526) was the defence against the increasing Ottoman threat

‘This was accompanied by the decline of royal power, which was nat

rally not unconnected with the growing importance of the Estates, The

‘wo personalities who dominated this petiod were the regent, John

Hunyadi (, 1456), hero of the Otoman wars, and bis som, King

Matthias Corvinus (1458-1490), who is remembered. lest asthe

conqueror of Vienna than asa generous patron of Renaissance art and

humanism. The union with Bohemia under the feeble Jagiellonian

Kings (1490-1526) was merely a prelude to the fll of the medieval

kingdom,

SOURCES

‘The history of Hungary is poorly endowed with narrative sources. Even

those that we have are not very informative. There are almost no

‘monastic annals and no family chronicles. Diaries, memoirs and other

‘genres of historical literature are also unavailable. Up to the end of the

fifteenth century, no period is illuminated by more than a single

account, with the exception of one decade (1345-1355), which is

covered by two works. Moreover, there are certain periods, such as that

between 1150 and 1270, for which there is no narrative source at all,

but only short chronological notices marking the dates of accession

and death of successive rulers. The oldest texts can only be recon-

structed from later redactions, and there will always remain a good

deal of uncertainty around them, An example is the putative ‘Primeval

ggesta’, now lost but usually dated to the eleventh century. Those works

that have survived, like the Gesta of Simon Kérai (c. 1285), the Ilumi-

nated Chronicle (¢. 1360) or the Chronicle of John Thuréczy (1488)

give only a brief and fairly terse report of events. The longest,

‘Thurdczy's Chronicle, which covers the period from Attila to Corvin

could be published quite comfortably in a single volume of modest

‘The Hungarian narrative sources do not, therefore, provide suffi

ient detail for the proper reconstruction of events, a fact that explains

why contemporary foreign sources are often of great importance, For

the first centuries of Hungarian history the annals of certain German

and Russian monasteries, as well as Byzantine, Dalmatian, Austrian

and Bohemian chronicles, are especially rich in information

concerning Hungary. Equally indispensable are the writings of some

later authors, like the chronicle of the Florentine Villani brothers for

the Angevin period or that of the Polish Jan Dlugosz for the age of the

Hunyadis. As regards the political situation in the decades immediately

preceding the battle of Mahaes, particulaely informative are the diploy

matic correspondence and reports of foreign (Venetian, Papal,

Austrian, and Polish) envoys. From the beginning of the thirteenth

insignificance of the narrative sources is somewhat

counterbalanced by a distinctively Hungarian type of source, namely

the narratives incorporated in royal grants of privileges. These docu-

ments provide valuable information on the ‘meritorious deeds

performed by the grantee in the campaigns of the king. Some of these

accounts are quite lengthy, covering several years, and often illuminate

‘events for which no other sources are available.

Unlike the narrative sources, the archival material of medieval

Hungary is, with the exception of the earliest period, relatively exten-

sive. From the cleventh and twelfth centuries, apart from some

important collections of laws, only a handful of ¢

favour of ecclesiastical institutions, have been preserved; but the

number of documents increases rapidly from around 1200 when the

laity began to feel the necessity of putting down their property (and

other) rights in a written form. As a result, roughly 10,000 documents

have survived from the chirteenth century and about 300,000 from the

period berween 1301 and 1526. About half of this corpus is now

preserved in the Hungarian National Archives at Budapest, the rest

being scattered in collections within Hungary and abroad, mostly in

Vienna, Bratislava, Cluj and Zagreb. (Photographic copies of all of

century the relati

arters, issued

them are available in the Hungarian National Archives) Most ofthese

documents are unpublished, and atleast haf have not been inven

Fied. OF the other archives where sources concerning the history of

medieval Hungary are tobe found, the most important are those ofthe

Vatican, which ill cannot be sid to have been fully exploited

The documents in question were party the products of central

administration and jurtliction, and partly records of legal transi

tions between private persons and institutions, ‘The use of written

administrative documents, in the first place the issue of royal writs,

began sporadically under the lat Arpadians and became a daily

routine der the Angevins. By that time the central courts had also

adopted the methods employed by the chancellery and began to

produce thousinds of Teters ordering inquires, prorogations and

compensations, of pronouncing final decsions for the interested

partes. The orders issued by the chancellry and the courts were

Carried out by local ecclesiastical institutions, called ‘places of authenti-

cation’ (loa crediila), which at the same time performed a notary

office function, drawing up contracts becween indvial parties

The documents that have come dawn tows represent only one oF 60

per cent of those that were once isued. Private collections that had

never been accessible to scholars were destroyed as late as the Second

World War Many docwments, judged irctovant for one tea oF

another, have been thrown away during the course of the cencuies,

among them the bulk of private letters and papers concerning mano.

Fal administration. Be the greatese destruction ofall seem to have

been caused by the Ottoman conquest in the siteenth century. All the

archives that were not removed in time from the path of the invading

army disappeared without trace. This i what happened to the most

important and probably greatest collection of the realm, namely the

documents of central administration that had previously been

preserved at Buda. This lost collection included the private and diplo-

mati correspondence of kings (only some leters of Matthias Convio

have survived in a codex), the volumes in which charters and writs

issued by the chancellery had been registered sine the Angevin period

(the Hungarian equivalent of the English chancery roll), and the

Iwhole of the chambers administrative records, including tax asses

ment lists. (Although certain sections of the archives were. probably

only burned during the siege of Buda in 1686, they had remained inac-

cessible under Ottoman rile) Most of the material that has survived,

therefore, consists ofthe private archives of maghate and gentry fami

lies, and, to a certain extent, those of ecclesiastical institutions and

municipalities. The majority of the documents concern western ad

northern Hungary, Slavonia (part of modern Croatia) and ‘Tansyl-

Vania. They are for the most part legal documents issued by places Of

authentication, the chancellery or the courts, and are generally written

in Latin, the official language of multinational Hungary until 184. It

was only in a few cities, like Sopron or Pressburg (Bratislava), that

German was used for internal affairs from the fourteenth century. As

for Hungarian, it did not emerge as an instrument of written commu-

nication before the early modern period, and even then only as the

language of private correspondence and local administration,

LIMITS OF MODERN RESEARCH

The possibilities of modern historical research are, therefore, fairly

limited. It is as if the history of medieval England had to be written

without access to the Public Record Office or the archives of the

southern counties. Compared to Russia or the Balkan states, however,

where medieval documents are counted in hundreds, Hungary is well

endowed with records and the predicament of a historian unquestion-

ably advantageous. The source material is particularly suitable for

historical research focusing on government or the land-owning classes.

We have relatively abundant chronological, archontological and proso-

pographical information from the thirteenth century onwards, and the

Picture we can draw becomes still more detailed from the Angevin

period, when the great majority of documents were already being

dated by the day of issue. (Between 1308 and 1323, for example, only

fone document in fourteen was issued without indication of the day.)

Lists of prelates and principal lay officeholders can be established rela-

tively fully from 1190 onwards with the help of the names of dignitaries

included in royal grants. ‘The reconstruction of royal itineraries, the

main source of late medieval political history, is only made possible

from 1310 by the increasing number of royal charters. The genealogy

of many noble families can be pieced together from the thirteenth

century, but only in the male line, since daughters are rarely

mentioned before the fifteenth century. From the late medieval period

we have scattered biographical data concerning several thousand

people belonging to the elite, but exact dates of birth and death can

rarely be established outside the royal family before the end of the

Middle Ages.

In contrast to the history of administration and of the nobility, the

economic and demographic conditions of the medieval period remain

obscure. No comprehensive register of the taxpayers or the settlements

of the medieval kingdom is known to exist. The only surviving source of

this kind are the lists, drawn up by the papal tax collectors sent from

Avignon between 1332 and 1337, of the parishes of the Hungarian bish-

optics and of the tax paid by them. However, the historical importance

of these lists lies primarily in the sphere of ecclesiastical geography.

Moreover, they do not cover all bishoprics. Rolls enumerating all the

landowners of the country and their peasant households by counties

and villages are supposed to have been drawn up regularly for military

‘or fiscal purposes since the reign of Sigismund of Luxembourg (1387—

1437), but only a few pieces have survived before 1531. As for the reve-

rues of the kingdom, a rough estimate can be made for the last years of

Sigismund’s reign, but the earliest detailed evidence comes from the

accounts of the treasurer Sigismund Ernuszt, bishop of Pécs, concerning

the years 1494-95. They contain, among other things, the number of

peasant holdings in the kingdom and their distribution by counties

‘What of local economic conditions? The recording of seigneutial rev

rnues in written form was exceptional before the end of the fifteenth

century, and even thereafter few lords kept regular accounts, This fact

enhances the value of the accounts that were prepared for Cardinal

Ippolito Este, archbishop of Esztergom and bishop of Eger (d. 1520),

by his Italian stewards in Hungary. For the everyday life of the peasantry

wwe have innumerable allusions scattered among the archives of noble

families, due to the fact that every lord went to law personally in cases of

damage done to, or caused by, his peasants, What we lack in this respect

is documentary evidence of a more coherent nature, such as records of

lawsuits pursued before the seigneurial courts. Recor. of this kind do

not seem to have been produced. Much more is known about urban life,

thanks to some carefully preserved archives. From the reign of Louis the

Great (1342-1382) onwards, municipal tax assessment lists, accounts,

wills and other documents have survived in increasing numbers and for

the most part remain unpublished.

Given the particular nature of the written sources, the evidence

provided by other disciplines is indispensable, especially for the tenth

to twelfth centuries. Archaeology has developed rapidly since the

1940s, producing important results, despite being forced until the end

of the Communist era to dispense with its most effective tool, aerial

photography, because of its political and military implications, Another

related discipline is linguistics, or more exactly toponymy, whose

evidence is simply indispensable for the reconstruction of the topog-

raphy and ethnic structure of medieval Hungary. The memory of

thousands of vanished settlements and other place names has been

preserved in medieval and early modern documents, and most of them

can be localised by reference to modern maps and by collecting still

surviving toponyms. Although the ancient network of settlement in the

southern regions had been practically destroyed by the end of the

Otcoman occupation, the tax assessments from the first period of

Ottoman rule (1540-1590) help us to reconstruct late medieval

conditions.

You might also like

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5795)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1091)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Weimar Culture - Gay, Peter PDFDocument231 pagesWeimar Culture - Gay, Peter PDFTugba Yilmaz100% (9)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- (Bob Brier, Hoyt Hobbs) Daily Life of The Ancient PDFDocument330 pages(Bob Brier, Hoyt Hobbs) Daily Life of The Ancient PDFdrunkenswordNo ratings yet

- Derek J. de Solla Price - Little Science, Big Science (1965, Columbia University Press) PDFDocument65 pagesDerek J. de Solla Price - Little Science, Big Science (1965, Columbia University Press) PDFpublishedauthor555No ratings yet

- Greece in BallkansDocument30 pagesGreece in BallkansDorian KoçiNo ratings yet

- Neoplatonism in Relation To Christianity, An Essay, Ch. Elsee, 1908Document168 pagesNeoplatonism in Relation To Christianity, An Essay, Ch. Elsee, 1908mihneamoise100% (3)

- History of Spanish Slavery in The Philippines - Wikipedia PDFDocument20 pagesHistory of Spanish Slavery in The Philippines - Wikipedia PDFAngelica VillorenteNo ratings yet

- Timeline of The Philippine Foreign RelationsDocument3 pagesTimeline of The Philippine Foreign RelationsJan ne50% (2)

- CFHB 2-A. Agathias. The Histories (1975) PDFDocument186 pagesCFHB 2-A. Agathias. The Histories (1975) PDFMarie DragnevNo ratings yet

- Sucesos Report OutlineDocument5 pagesSucesos Report OutlineLuigi Francisco100% (1)

- Eurasian Studies English Edition II EditDocument333 pagesEurasian Studies English Edition II EditBahuvirupakshaNo ratings yet

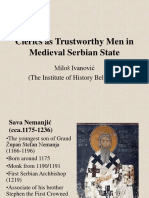

- Clerics As Trustworthy Men in Medieval Serbian State: Miloš Ivanović (The Institute of History Belgrade)Document9 pagesClerics As Trustworthy Men in Medieval Serbian State: Miloš Ivanović (The Institute of History Belgrade)Milos IvanovicNo ratings yet

- M. Ivanovic - Foreigners in Service of Despot DjuradjDocument12 pagesM. Ivanovic - Foreigners in Service of Despot DjuradjMilos IvanovicNo ratings yet

- Foreigners in The Service of Despot Đurađ Branković On Serbian TerritoryDocument12 pagesForeigners in The Service of Despot Đurađ Branković On Serbian TerritoryMilos IvanovicNo ratings yet

- Ivanovic - The Commune of Ragusa and Ottomans PDFDocument21 pagesIvanovic - The Commune of Ragusa and Ottomans PDFMilos IvanovicNo ratings yet

- Anjoykori V, 431.Document1 pageAnjoykori V, 431.Milos IvanovicNo ratings yet

- Cast in Bronze and Stone: BibliographyDocument27 pagesCast in Bronze and Stone: BibliographypatavioNo ratings yet

- MeliandialougeessayDocument4 pagesMeliandialougeessayapi-276296302No ratings yet

- SAQ Information and InstructionsDocument3 pagesSAQ Information and InstructionsAJ CepadaNo ratings yet

- Rainfall Cycles in Ancient IndiaDocument4 pagesRainfall Cycles in Ancient IndiaNarayana Iyengar100% (3)

- 14 BibliographyDocument15 pages14 BibliographySrinivas Madala100% (1)

- Young Men S Christian Association of Manila20210505-13-101idx6Document6 pagesYoung Men S Christian Association of Manila20210505-13-101idx6Geanibev De la CalzadaNo ratings yet

- Three Age SystemsDocument6 pagesThree Age SystemsKeila AntonioNo ratings yet

- IE 1101 Group 2 Emilio Aguinaldo Hero or GangsterDocument11 pagesIE 1101 Group 2 Emilio Aguinaldo Hero or GangsterLiway Generoso100% (1)

- Richard II History or TragedyDocument7 pagesRichard II History or Tragedy0000 0000No ratings yet

- Heneral Displays A Regime That Is Driven With Nepotism. It Questions The Very Value ofDocument2 pagesHeneral Displays A Regime That Is Driven With Nepotism. It Questions The Very Value ofPaul KilaykoNo ratings yet

- 13 Colonies: Teacher's GuideDocument12 pages13 Colonies: Teacher's GuideNayeli VeraNo ratings yet

- Non-Cooperative Games John F. Nash, Jr. Annals of Mathematics, Vol. 54, No. 2, Sept 1951 Presented by Andrew HutchingsDocument16 pagesNon-Cooperative Games John F. Nash, Jr. Annals of Mathematics, Vol. 54, No. 2, Sept 1951 Presented by Andrew HutchingsrajeshkannanspNo ratings yet

- Antecedents of Sui Tang Burial Practices PDFDocument53 pagesAntecedents of Sui Tang Burial Practices PDFAndreaMontella100% (1)

- The Funambulist 48 - Fifty Shades of White (Ness) - Digital Version (Small Res)Document43 pagesThe Funambulist 48 - Fifty Shades of White (Ness) - Digital Version (Small Res)Tulio RosaNo ratings yet

- Bayaning Third WorldDocument10 pagesBayaning Third WorldIana Kristine Evora100% (1)

- (NOTES 1) What Is HistoryDocument2 pages(NOTES 1) What Is History2A - Nicole Marrie HonradoNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1: IntroductionDocument3 pagesChapter 1: IntroductionCamille BonsayNo ratings yet

- Ancient Indian ScienceDocument23 pagesAncient Indian Scienceyogesh shindeNo ratings yet

- Anna Green ReviewDocument3 pagesAnna Green ReviewMarco Alvarez ZuñigaNo ratings yet

- History of Syria: PrehistoryDocument8 pagesHistory of Syria: Prehistorykamill1980No ratings yet