Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Safe - Eyline 42 (Winter 2000)

Uploaded by

Christopher BraddockCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Safe - Eyline 42 (Winter 2000)

Uploaded by

Christopher BraddockCopyright:

Available Formats

Kyla McFarlane looks at the recent art of Christopher Braddock

<D

"<

<D

:J

<D

.i:..

I\)

c

-+

c

3

::J

---~

::J

-+

(])

I\.)

0

O

(.I)

~

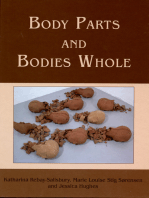

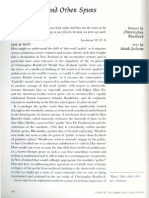

Pinched, 1999. Detail. Tin, 199.5 x 37 cm.

Courtesy Gow Langsford Gallery, Auckland

SAFE. The word suggests comfort, security and

trust. It alludes to an emotional and physical space

where danger has no place, where secrets are kept

and fears are allayed.

Safe ( 1999) is the title of a recent work by sculptor Christopher Braddock which explores the possibilities and limitations of such a space. Braddock

examines the notion in all its contradictions, recognising that to be safe can offer certain freedoms, but

also that playing it safe demands caution or reserve

and requires us to reside within set boundaries and to

play by others ' rules.

The work was exhibited in a small, narrow room

at the Gow Langsford Gallery in Auckland, in which

Braddock hung a row of square tin boxes along the

wall. Commercially constructed by a tin smith, the

boxes reflected the shape, size and substance of biscuit tins, or metal safes where personal valuables are

stored- repositories for the precious material evidence of memory and experience.

Yet experience cannot always be measured by

material things and Braddock ' s sculpture also

engaged with the possibility of emotional and spiritual safety. The work brought a sense of the private,

secret space of the confessional into the public, secular space of the gallery through a series of references

to Catholicism. As the metal commonly used to

make inexpensive, mass-produced Catholic votive

offerings, Braddock's use of tin connected the work

to the iconography of this belief system, a system in

which prayer and worship encourage a sense of personal security and comfort. Further to this, Braddock

embossed a mutation of the confessional's grill on

the lid of each box. Rendered in the shape of a cross

constructed from four phallic shapes, their forms are

made explicit by a series of holes drilled through the

metal sheet. Hung at ear height, the placement of the

tins immediately suggested an alignment between

the objects and the physical presence of the viewer.

As the viewer entered this narrow space, and proceeded to move past each of the boxes, there was a

strong temptation to press one' s ear-or mouth- to

each grill, in order to hear-or speak- a request for

forgiveness. The banal seriality of the boxes also

gestured towards the unnerving suggestion that these

requests for atonement might become, through repetition, a hollow rehearsal of words , or worse , a

pathological compulsion.

Braddock's artistic project, at the heart of which

is an extended critical dialogue with the rituals of

institutionalised Catholic devotion, is thrown sharply

into relief against the current backdrop of the secularised culture of confession and confusion over

what we might still be able to believe in- if anything. Braddock is, in his words, 'a believer', and

was brought up as an Anglo-Catholic. His position

has been described as 'involved but poised on the

edge of institutionalised religion-displaying a profound distrust of fundamentalist strains of belief with

restricted attitudes toward, for example, issues of

sexuality and authority' . 1 Such a critique also has

much to say about the secular world and the boundaries it draws up in order to delineate between the

'guilty' and the 'acquitted' .

In his pursuit of this critique, Braddock works

obsessively with a repertoire of personal symbols.

He has worried over them and played with them for

several years now, formulating his own sculptural

language with the use of stencils and moulds, transforming a small number of basic forms into a large

number of configurations. The result is a series of

symbols which are, to the viewer, both familiar and

unsettling. They occupy a space between the formalist and the figurative, the sacred and profane, the

public and private, typified by the formation of the

phallic crosses in Safe. In these forms, the corporeal,

sexualised body is merged into the institutionalised

symbolism of Catholicism, where certain representations of the body are traditionally denied. In doing

this, Braddock challenges the boundaries that formalise such rigid categorisations, suggesting that

there might be passages between them. His sculptures offer the possibilities of moving away from

these institutionalised limitations to a space where

the languages and remainders of each system begin

to merge, giving prominence to that which is denied

or disapproved of by the dominant system.

Pin ched ( 1999), exemplifies these concerns on

several levels. From a distance, it appears to be

dense, stiff, priapic. But such solidity is deceptivea trick of the eye. Close up , Pinch ed exudes not

strength, but the delicate, shimmering glitter and

shine of Christmas tree decorations, which in themselves are the result of the commercialisation of one

of Christianity ' s most sacred days . To create this

effect, Braddock has delicately, lovingly, pieced

together a series of tin heart-like shapes like a

delighted child dressing a favourite paper doll, interlocking each form by linking up and carefully folding over small metal tabs that protrude from each .

The result is a fragile corset for which there is no

torso, an armour that tightens itself around a body

whose presence can only be imagined . All that

remains are the repeated, partial forms ofBraddock's

obsession- it is with them that his pleasure lies.

The flux between the apparent stiffness of this

work and its actual lightness and fragility also suggests a critique of sexual roles and privileges within

the hierarchy of the church . The apparent phallic

strength of Pinched is, simply, a masquerade, giving

way to a hollow structure that offers little behind its

glittering fa9ade . But it is in such trickery that this

His sculptures offer the

possibilities of moving away from

these institutionalised limitations

to a space where the languages

and remainders of each system

eye Ii n e 4 2

begin to merge ...

Above: Votive Mutations,

1999. Tin , ribbon and

chromed steel. 31 parts,

dimensions variable.

Courtesy Gow Langsford

Gallery, Auckland

Left: Pinched, 1999. Tin ,

199.5 x 37 cm. Courtesy

Gow Langsford Gallery,

Auckland

autumn I winter 2 o o o

135

Safe, 1998-99. Tin, 27 x 27 x 12 cm each.

Courtesy Gow Langsford Gallery, Auckland

work gains its strength, for that which is absent is as

powerful as the structure that surrounds it. Braddock

knows his tower is built on unstable ground, almost

to the point of declaring outright that the entire structure of belief it is built upon is pure fiction. Yet he

resists this temptation and continues to construct it,

offering it up for display. Is this an act of blasphemy,

or veneration? We might be tempted to suppose that

it is both, allowing Braddock to have it both ways.

By memorialising something that might never have

existed, in constructing a work such as Pinched,

Braddock applies the logic of the classic Freudian

fetishist, allowing him to simultaneously assume an

ironic, critical distance whilst engaging in an act of

devotion. He then stands back to admire his glorious

display.

Fetishism is also a subtext to Votive Mutations

(1999). Hung from stainless steel hooks protruding

at various heights from the gallery wall, strange tin

forms bound up in deep purple ribbons were presented as memorials or offerings, resembling the phantasmagorical sight of valuable commodities on display in a shop window. The rich colour of the ribbons had liturgical associations, reminiscent of the

power and authority of the bishop's dress. They also

were suggestive of bookmarks placed neatly between

the pages of well-thumbed Bibles, marking out verses to be read and contemplated. Bound up in these

rich purple bands, which speak of religious devotion

and solemn engagement with Biblical texts, were the

forms of sexualised body parts-the penis, the buttocks- tangled up with imagery from traditional

Catholic votive objects.

Julia Kristeva has contended that 'when you

have a coherent system, an element which escapes

from a system is dirty' .2 This is one way of accounting for the mixed metaphors in Votive Mutations. In

denying the body, particularly with respect to aspects

Duct, 1999. Tin, 13.5 x 17 cm.

Courtesy Gow Langsford Gallery, Auckland

of its sexuality, the institution of the church sets the

body apart from itself, excluding it and assigning it

as abject and base. In response, Braddock reinscribes

a place for the excessive and the abject body within

the system by offering his mutations up for adoration

in the same way icons are presented in the niches of

churches. Votive Mutations then becomes an art of

excess, an art that attempts to represent that which

exceeds the structures of institutionalised devotion.

The effect is similar to that achieved in Pinched,

with the tensions created between the sacred and

profane providing the work with its power.

In his discussion of abjection and trauma in The

Return of the Real, Hal Foster observes the dangers

in 'the restriction of our political imaginary to two

camps , the abjectors and the abjected, and the

assumption that in order not to be counted among

sexists and racists one must become the phobic

object of such subjects' . 3 Braddock avoids such

binary oppositions by placing a certain amount of

faith in the notion of transformation. At a time when

the definition of the body is being reimagined by the

sciences of cloning and genetics and a cure for the

AIDS virus has not yet been found, Braddock ' s

sculptures encapsulate the state of flux and fragility

that characterises the physical body in our age, but

they also assert a certain idealism. This is evidenced

in the work by the expression of the belief that transformation from the profane to the sacred, or from an

outside to an inside, (or margin to centre) is still a

possibility.

Duct I- V ( 1999) is interesting in this conceptual

context. In this work, small tin 'dishes' were set into

the walls of the gallery, situated close to the floor at

various points around the room. At the centre of

each, drilled holes formed a vent through which

something (sound, air, waste?) might pass. Unlike

the confessional grills in Safe, the function of these

tiny passageways was unclear, other than to facilitate

an escape from, or to, the gallery space. Although

they were only the size of a hand, their presence

opened up the space, allowing it to breathe.

Perhaps Braddock's position is most clearl y

expressed in a work such as Votive Mutations, where

anxieties surrounding the body, and the notion of

unquestioning faith are bound up in these strange,

fragile offerings. These objects, with their confused

forms that lie between the secular and the sacred,

might just be the perfect talismans to accompany us

as we collectively embark on our obsessive bid to

tell all, hear all , confess our sins to anyone who

might listen or bear witness to them. Underlying all

of Braddock's work is a conviction that it is possible

to forgive these sins; to move from playing the role

of the guilty to that of the absolved- as long as we

are prepared to embrace the possibility that there

might just be more than one truth, and more than one

authoritative voice asserting it. We cannot always

play it safe.

notes

I . Millar, Caspar, Voto, D ecember 1998.

2. Julia Kristeva, quoted in 'Of Word and Flesh', an interview by Charles Penwarden, Rites of Passage: Art for the

End of the Century, ed. Stuart Morgan and Francis Mo nris.

Tate Gallery Publications, London, 199 5, p. 24.

C hristopher Braddock's exploration of t he fragmented,

even mutilated body and his critique of the nat ure of

devotion and ritual closely connect his work to that o f

the artists included in this exhibit ion of the same name.

3. Foster, Hal, The Return of the Real, Cambridge MA,

MIT, 1996, p. 166.

Christopher Braddock is an Auckland base d

artist. Kyla Mcfarlane is a Ne w Zealand writer

currently based in Melbourne.

eyellne 42

a u t umn /w i n te'

200 0 136

You might also like

- Voto (1998)Document6 pagesVoto (1998)Christopher BraddockNo ratings yet

- Manikins Wobbling Towards Dismemberment Art and Religion - State of The UnionDocument5 pagesManikins Wobbling Towards Dismemberment Art and Religion - State of The UnionAlex Arango ValenciaNo ratings yet

- The Pathological Nature of The "Postmodern Condition"Document18 pagesThe Pathological Nature of The "Postmodern Condition"Emilio VelNo ratings yet

- Tumultuous Wayfarer A Review of On Philip K. Dick 40 Articles From SF-StudiesDocument4 pagesTumultuous Wayfarer A Review of On Philip K. Dick 40 Articles From SF-StudiesFrank BertrandNo ratings yet

- Dynamics of Desacralization: Disenchanted Literary TalentsFrom EverandDynamics of Desacralization: Disenchanted Literary TalentsPaola PartenzaNo ratings yet

- Waiting For Godot A Deconstructive Study PDFDocument22 pagesWaiting For Godot A Deconstructive Study PDFFarman Khan LashariNo ratings yet

- Tezcatlipoca: Trickster and Supreme DeityFrom EverandTezcatlipoca: Trickster and Supreme DeityRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- The House As Skin (TEX) - Laura ColombinoDocument12 pagesThe House As Skin (TEX) - Laura ColombinoMaciel AntonioNo ratings yet

- SeeingMedievalArt GillermanDocument4 pagesSeeingMedievalArt GillermanMac McIntoshNo ratings yet

- Evental Aesthetics Vol. 2 No. 1, Premodern AestheticsDocument104 pagesEvental Aesthetics Vol. 2 No. 1, Premodern AestheticsEvental Aesthetics100% (1)

- Project Muse Permission To Post This Image Online.: Spiritus - 4.2Document16 pagesProject Muse Permission To Post This Image Online.: Spiritus - 4.2Claudiu TarulescuNo ratings yet

- The Late Style of Edward SaidDocument10 pagesThe Late Style of Edward Saidstathis58No ratings yet

- Song and Self: A Singer's Reflections on Music and PerformanceFrom EverandSong and Self: A Singer's Reflections on Music and PerformanceNo ratings yet

- Benedict Anderson Book ReviewDocument7 pagesBenedict Anderson Book ReviewSpyros KakouriotisNo ratings yet

- The Origin of The WorldDocument3 pagesThe Origin of The WorldmarkbrittainNo ratings yet

- Foreign Bodies: Performance, Art, and Symbolic AnthropologyFrom EverandForeign Bodies: Performance, Art, and Symbolic AnthropologyNo ratings yet

- Midwest Modern Language Association The Journal of The Midwest Modern Language AssociationDocument17 pagesMidwest Modern Language Association The Journal of The Midwest Modern Language AssociationKNo ratings yet

- Blake & Orthodoxy Daniel GustafssonDocument18 pagesBlake & Orthodoxy Daniel GustafssonМихаил ПаламарчукNo ratings yet

- Thesis On Waiting For GodotDocument6 pagesThesis On Waiting For GodotWriteMyPaperCoCanada100% (2)

- Iconographic ThesisDocument7 pagesIconographic Thesisdonnakuhnsbellevue100% (2)

- 3031858Document3 pages3031858mohammadNo ratings yet

- Professor Lois Gordon - Reading Godot (2002) PDFDocument225 pagesProfessor Lois Gordon - Reading Godot (2002) PDFRowanberry11100% (1)

- Museums, Poetics and AffectDocument21 pagesMuseums, Poetics and AffectRana GabrNo ratings yet

- A Marriage of Heaven and Hell, Blake's Myth of Satan and Its Cultural MatrixDocument18 pagesA Marriage of Heaven and Hell, Blake's Myth of Satan and Its Cultural MatrixImre Viktória AnnaNo ratings yet

- Literature 02 00020Document18 pagesLiterature 02 00020eimiNo ratings yet

- Walter Benjamin The Kabbalah and SecularDocument2 pagesWalter Benjamin The Kabbalah and SecularCristian RojasNo ratings yet

- Gombrich - The Use of Art For The Study of Symbols PDFDocument17 pagesGombrich - The Use of Art For The Study of Symbols PDFAde EvaristoNo ratings yet

- Essays On Wit No. 2 by Flecknoe, Richard, 1600-1678Document31 pagesEssays On Wit No. 2 by Flecknoe, Richard, 1600-1678Gutenberg.orgNo ratings yet

- On Deconstruction: Theory and Criticism after StructuralismFrom EverandOn Deconstruction: Theory and Criticism after StructuralismRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (25)

- Committment To FormpdfDocument5 pagesCommittment To FormpdfAnonymous IddV5SAB0No ratings yet

- Sartor Resartus, and On Heroes, Hero-Worship, and the Heroic in HistoryFrom EverandSartor Resartus, and On Heroes, Hero-Worship, and the Heroic in HistoryNo ratings yet

- Aesthetics and the Incarnation in Early Medieval Britain: Materiality and the Flesh of the WordFrom EverandAesthetics and the Incarnation in Early Medieval Britain: Materiality and the Flesh of the WordNo ratings yet

- The Sun Went inDocument32 pagesThe Sun Went indezbatNo ratings yet

- Research Paper On Waiting For GodotDocument6 pagesResearch Paper On Waiting For Godotgw0q12dxNo ratings yet

- Conferring With The DeadDocument11 pagesConferring With The Deaddidi bluNo ratings yet

- Baroque CasuistryDocument17 pagesBaroque CasuistryLesabendio7No ratings yet

- Re 2014 15LectureThreeYeatsDocument7 pagesRe 2014 15LectureThreeYeatsDan TacaNo ratings yet

- Magdalena Cieslak, Magdalena Cieslak, Agnieszka Rasmus-Against and Beyond - Subversion and Transgression in Mass Media, Popular Culture and Performance-Cambridge Scholars Publishing (2012)Document197 pagesMagdalena Cieslak, Magdalena Cieslak, Agnieszka Rasmus-Against and Beyond - Subversion and Transgression in Mass Media, Popular Culture and Performance-Cambridge Scholars Publishing (2012)Tamara Tenenbaum100% (2)

- Galla Placidia AestheticsDocument20 pagesGalla Placidia AestheticsYuliya TsutserovaNo ratings yet

- 反对与超越:大众媒体、大众文化与表演中的颠覆与穿越Document197 pages反对与超越:大众媒体、大众文化与表演中的颠覆与穿越周安No ratings yet

- The Classical Quarterly: Refuted and Cynic TraditionDocument12 pagesThe Classical Quarterly: Refuted and Cynic TraditionMariaFrankNo ratings yet

- 'Of Genius', in The Occasional Paper, and Preface to The CreationFrom Everand'Of Genius', in The Occasional Paper, and Preface to The CreationNo ratings yet

- Lena Petrović Derrida's Reading of Levi StraussDocument10 pagesLena Petrović Derrida's Reading of Levi StraussAnanya 2096No ratings yet

- The Sacrament of Desire: The Poetics of Fyodor Dostoevsky and Friedrich Nietzsche in Critical Dialogue with Henri de LubacFrom EverandThe Sacrament of Desire: The Poetics of Fyodor Dostoevsky and Friedrich Nietzsche in Critical Dialogue with Henri de LubacNo ratings yet

- Ernst Cassirer - The Individual and The Cosmos in Renaissance Philosophy-Dover Publications (2011) PDFDocument225 pagesErnst Cassirer - The Individual and The Cosmos in Renaissance Philosophy-Dover Publications (2011) PDFf100% (1)

- Niklas LovgrenDocument26 pagesNiklas LovgrenEstefania MancipeNo ratings yet

- Contagious Participation Magic's Power To Affect (2011)Document12 pagesContagious Participation Magic's Power To Affect (2011)Christopher Braddock100% (1)

- The Artist Will Be Present (2008)Document236 pagesThe Artist Will Be Present (2008)Christopher BraddockNo ratings yet

- Sanitate (2004)Document34 pagesSanitate (2004)Christopher BraddockNo ratings yet

- The Artist Will Be Present (2007)Document8 pagesThe Artist Will Be Present (2007)Christopher BraddockNo ratings yet

- Inn House (2003-2004)Document42 pagesInn House (2003-2004)Christopher BraddockNo ratings yet

- Random Entrant - FRAKCIJA 50 (2009)Document8 pagesRandom Entrant - FRAKCIJA 50 (2009)Christopher BraddockNo ratings yet

- Incised Skin - Gothic NZ (2006)Document9 pagesIncised Skin - Gothic NZ (2006)Christopher BraddockNo ratings yet

- Fleshly Worn (1995)Document12 pagesFleshly Worn (1995)Christopher BraddockNo ratings yet

- Connecting Issues - Art NZ 78 (Autumn 1996)Document4 pagesConnecting Issues - Art NZ 78 (Autumn 1996)Christopher BraddockNo ratings yet

- Emmeshed - Art NZ 72 (Spring 1994)Document4 pagesEmmeshed - Art NZ 72 (Spring 1994)Christopher BraddockNo ratings yet

- Above - Faking It (2008)Document5 pagesAbove - Faking It (2008)Christopher BraddockNo ratings yet

- Christopher Braddock - Gow Langsford (1992)Document16 pagesChristopher Braddock - Gow Langsford (1992)Christopher BraddockNo ratings yet

- Alicia Frankovich and The Force of Failure - Column 5 (2010)Document8 pagesAlicia Frankovich and The Force of Failure - Column 5 (2010)Christopher BraddockNo ratings yet