Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Reeds How To Care For Them

Reeds How To Care For Them

Uploaded by

maikel_morelliOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Reeds How To Care For Them

Reeds How To Care For Them

Uploaded by

maikel_morelliCopyright:

Available Formats

Reeds

How To Care For Them and How

To Improve Their Response

Floyd Williams

The purpose of this article is not to

outline a detailed, complex method for

fixing clarinet reeds. This has been done

and is still being done by a number of

writers on this subject. Some of the books

which describe reed-fixing are listed in the

bibliography. They should all be read

because it is necessary for every clarinettist

to understand a variety of ideas to arrive at

their own approach to working on reeds.

Here are some simple, but effective

procedures which will make more reeds

respond better and last longer.

Reeds last longer and play better when

stored in a stable environment. When they

are allowed to dry out excessively or soak

up too much moisture, they warp. Dont

confuse warping with a wrinkled tip which

occurs when the reed is first wet. This

wrinkling is an indication that it has been

allowed to dry out too much. It probably is

warped if this happens, but it is mainly

useful as a general indication of lack of

sufficient moisture in the reed during

storage.

A simple solution to maintaining

moisture in reeds is to keep reed cases/

holders in a re-sealable plastic bag or small

food storage box. It is important to dry the

reeds off before putting them away as they

will warp in a concave manner if too wet

and, of course, mildew and mould could

be a problem also.

I dont think that storing reeds in holder/

cases that rely on a flat surface is of any use,

and could cause problems. A reed which is

slightly damp on the bottom will dry faster

on the top surface than the bottom and

this stress could exacerbate the tendency to

warp. An economical solution is to find a

suitably sized food storage container, put a

strip of BluTac at the ends and simply stick

the butt of the reed into the BluTac so it is

held on its side. That way, the reed dries

evenly.

A warped reed is one which is no longer

flat on the back. This flat back is a

requirement if it is to seal adequately to the

table of the mouthpiece while vibrating. If

allowed to dry out too much, it will warp

convexly, if too wet, concavely. The usual

problem is a convex warp.

You may test for convex warpage by

placing the reed on a perfectly flat surface

(a piece of glass will do nicely) and checking

for any sign of rocking back and forth from

side to side. Even a seemingly slight amount

of rocking is not good. You may also place

it on the mouthpiece, wet the heel of your

hand, place the bore end of the mouthpiece

on your hand and suck on the mouthpiece

in order to create a partial vacuum inside

the mouthpiece. If the reed is flat enough,

it will be forced to the mouthpiece and stay

there for about two or three seconds before

it overcomes the vacuum and snaps back

away from the mouthpiece with a pop. If

it doesnt, it is leaking somewhere along the

sides.

Slightly warped reeds can be fixed at the

expense of softening them slightly. If warped

too badly, especially convexly, throw them

away.

A second cut or more conveniently

June 2003

sized flat bastard file is useful for fixing a

slight warp or the slight flattening and

smoothing of the bottom of new reeds.

Place the reed at the pointed end of the file

and keep the upper half of the reed on the

smooth surface at the end of the file. Let

the sanding touch the lower half of the reeds

back. Place your fingers lightly on the reed

and sand in a back and forth motion. Do a

little at a time and check to see if the reed is

flat. After it has been flattened, you may

have to clip it slightly if it has become too

soft. On new reeds you may place the entire

reed on the file, as you will be removing

only a very small amount of wood.

The ideal solution for this problem is to

prevent the warp from occurring in the first

place. This problem can be minimised by

storing your reeds in a container which seals

tightly enough to prevent too rapid a

moisture exchange with the surrounding

environment. It may be that a zip-lock

plastic bag will be sufficient, or perhaps a

plastic refrigerator container of a convenient

size, as described earlier. All of these seal to

a different degree. Also, the number of reeds

kept in the container and how many of

them are played each day has an effect on

11

the results. This is due to the fact that the

reeds act as a moisture wick when they are

played and they still retain some moisture

when stored in a reed holder. A little

experimentation is required in order to

arrive at an acceptable degree of moisture

for the reeds. Obviously, it will vary if you

only have four reeds and practice every other

day. The reverse situation might involve 15

to 20 reeds in the container with several

reeds being played every day in practice.

The important thing is to be consistent

once you find something that works and

never leave the reeds out to dry, not even

for a few minutes, for example, while trying

reeds. Close the container.

If you get mildew on the reeds, the

container may be too tight or the reeds are

being put away too wet or the weather is

very humid. In some areas of the country,

none of the procedures mentioned above

are necessary because of high humidity,

especially in the summer. In other areas,

warping may only be a problem in the

winter with low levels of humidity in the

environment. It is not difficult to adjust for

these factors and the results are well worth

the effort. Your reeds will play better, last

longer and play more consistently from day

to day.

It will be most immediately useful to

discuss the ways in which a reeds response

can be improved without any special skill

with reed rush or a knife. These procedures involve the dimensions of the

reed (especially near the tip), the placement

of the reed on the mouthpiece, polishing

the reeds bottom, the shape of the reeds

tip and finally, the breaking-in process.

When you open a box of reeds to try

them, never play them for more than a few

minutes on the first day. During the first

five to seven days of a reeds life, avoid

playing it for more than ten minutes a day.

This allows the reed to become accustomed

to wetting and drying gradually and will

increase its useful lifespan. Adjustments can

12

be made during the break-in period, but

dont try to make it play in one session Do

the work gradually.

When the break-in period is over and

the new reed joins your other playing reeds,

alternate the reeds you are using each day.

Dont play a reed for hours at a time, day

after day. It will not last as long or be as

consistent as it would be if it is allowed to

rest, alternating with other playable reeds.

In order to use reeds in this fashion, you

must have playable reeds and reeds that are

in the process of being broken in. I would

suggest that you have on hand a minimum

of eight reeds at all times. For example, this

would give you four playing reeds and four

reeds which are being broken in. As the

playing reeds are used up, they are replaced

by properly broken-in reeds. This procedure

continues so that you never have to play a

performance, rehearsal, or a lesson on a new

or unadjusted reed.

Clarinet reeds play best with a tip width

of 13 mm. Some brands of commercial

reeds are closer to this measurement than

others when they are manufactured.

Adjusting the reed to this width is especially

helpful if the reed is a little too resistant or

hard. If the reed is soft, dont bother with

this adjustment.

Place the reed on its side on #320

sandpaper and sand it back and forth the

same number of strokes on each side.

Distribute the finger pressure so you dont

destroy the even taper of the reed towards

the tip. Counting the number of strokes

insures a reasonable degree of control over

the amount taken off each side. When the

reed is 13mm wide at the tip, round the

corners off with an emery board, being

careful to stroke towards the centre of the

tip only and not back and forth.

Next, lightly bevel (round off) the top

right and left edges of the reed from

shoulder to tip. On the bottom edges, one

or two light strokes of the sandpaper from

shoulder to tip will remove any burrs left

Australian Clarinet and Saxophone

by the sanding.

During the first day of a reeds life, the

bottom of the reed may swell slightly

towards the mouthpiece window, causing

the bottom of the reed to look rough and

grainy. Rubbing the reed very lightly on

the file or even on the back of a piece of

sandpaper (the non-abrasive side) will

restore a smooth surface to the reed. This

rough or grainy appearance can decrease

response. Be careful when using the file, as

you dont want to soften the reed. This

raising of the grain is similar to what

happens when you paint wood and then

must sand it smooth again between coats

of paint. You can help maintain a smooth,

hard surface on the back of a reed by

rubbing it down on paper after each use, if

necessary. Also, rubbing the top surface of

the reed with the finger or a smooth, round

object is a normal part of the breaking-in

process. This helps seal the open tubes at

the surface of the reed and helps form a

homogenous vibrating unit. Do this last

procedure on a piece of glass or any flat,

smooth surface.

An often neglected aspect of reed

adjustment involves the simple placement

of the reed on the mouthpiece. There are

five positions which should be tried to see

if one results in a better sound. These

positions are:

(1) positioning the reed a little to the left,

(2) a little to the right,

(3) slightly higher in relation to the tip,

(4) slightly lower, and

(5) what you consider your normal,

symmetrical placement on the

mouthpiece.

It might be helpful to mark reeds to

remind you of where they play best.

The next steps in reed adjustment require

a certain degree of skill and experience,

which can only be acquired by doing it.

Dont be afraid to try to make your reeds

play better. Remember, this skill is easier to

master than the time and effort you have

spent learning to play the clarinet, and it

will greatly improve your clarinet playing.

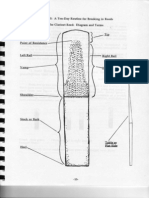

First, study the drawing below in order

to understand the parts of a reed which

constitute the main areas you will be

adjusting.

The ideal in reed fixing is to arrive at a

reed which is symmetrically balanced from

the shoulder to the tip. In other words, if

you draw an imaginary line down the

reed longitudinally dividing it in half,

each half will be the same. In the

following instructions, we will concern

ourselves with only the principal areas

shown in the diagram.

Brief Version of Henry Larsens Reed

Balancing Procedures

With the reed on the mouthpiece, twist

the instrument so that more embouchure

pressure is exerted on the right hand side of

the reed and play mp-mf low e and observe

the degree of resonance (clarity in the tone).

Remember, you will be hearing how the

left side of the reed responds.

Then, do the opposite, and see how the

right side compares to the left. The duller,

less resonant side needs to be scraped with

reed rush in the lower right or left triangle,

still with the reed in place.

When the right and left feel and sound

the same, then check to see how the B

natural a 12th higher sounds on each side.

If one is smoother and clearer, then scrape

a bit on the opposite side in the area shown

in the diagram as register smoothing.

After this plays to your satisfaction, test

open g in the same manner, but now you

will be scraping either the right or left upper

triangle.

You may find that playing a few adjacent

pitches to the low e and g will help you to

determine which side needs scraping with

reed rush. At this point, I might suggest

that you use reed rush dry. It is commonly

suggested that the rush be wet, pressed

down flat at one end and left to dry so it

remains flat. Ive never seen any particular

benefit to this procedure. To use it dry only

requires that the walls of the rush be

sufficiently thick to avoid crumbling under

the light pressure required to make an

adjustment.

For me, this makes most potentially

good reeds play well. You cant make all

reeds play perfectly by adjusting them. You

can make them play better, but the quality

of the cane and the even distribution of

xylem (tiny tubes that run up through the

cane) are very important factors which no

amount of adjusting will change.

(For a more detailed description, please

refer to the articles The Reed Connection,

Part I and II in The Clarinet July/August

1991 and November/December 1991 by

Henry Larsen.)

It is important to have a model reed in

mind before you begin adjusting a reed. If

the reed still doesnt play to your satisfaction,

more work in areas 1 and 2 may be

necessary. This may be an actual reed which

has given good service or a strong mental

image of what a good reed feels like when

you flex its tip and areas 1 and 2 with your

finger tip.

Assume we are working on a reed which

is a little too hard. If it is too soft, you can

only clip it. However, some reeds which

seem to be too soft really just need to be

properly balanced at the tip. If one side is

considerably harder than the other, it may

feel and sound as if it is soft, but when the

hard side is balanced with the softer side it

will most likely feel right and sound good.

Also, you may achieve this better balance

by narrowing the reed only on the soft side

and leaving the harder side alone. In fact,

you may have to narrow it in favour of the

softer side and balance the harder spots in

the tip area in order for it to feel right.

Remember, a reed which seems just right

or a bit soft on the first playing will probably

get more resistant during the first few days

of the breaking-in process. This is why you

should not do too much adjusting during

that period. Do not clip a soft reed until

you have balanced it

Ben Armato, in his book Perfect-a-Reed:

A Scientific Method for Reed Adjusting,

suggests that you not only feel for harder

spots on the tip, but look for the places that

bend less when you flex the tip or the area

back from the tip. This way of looking at it

may be easier than feeling the hard spots.

He also suggests marking them lightly with

a soft pencil so you easily see where to

scrape. Scraping off the light pencil mark is

about the right amount of wood to remove

at one time.

Adjust the tip until you can feel that it

flexes evenly across its width. It is acceptable

(perhaps desirable) for the mid-point of the

tip to be slightly harder than either side,

but only a little. You are generally looking

for an even deflection of the tip as you move

across it.

Always be sure your reeds tip is wellrounded to match the shape of your

mouthpiece. As a reed gets older, it may

develop a tendency to buzz and be noisy

in the lowest register of the instrument,

especially when playing softly. Try changing

the shape of the tip, that is, make the tip

more rounded in shape. This can also

change the tone of the reed to a darker, less

edgy sound in some instances. Use an emery

board for this and experiment.

Reed fixing is a very personal skill. Work

at it every day, but not at the expense of

practice. Read all the books and articles

listed in the bibliography and develop an

approach that works best for you.

Floyd Williams is editor of Australian

Clarinet and Saxophone and senior

lecturer in clarinet at Qld. Conservatorium

Griffith University.

Bibliography:

Armato, Ben. Perfect-A-Reed: A Scientific

Method for Reed Adjusting. Ardsley, NY:

Perfect-A-Reed, 1980.

Bonade, Daniel. The Art of Adjusting Reeds.

Kenosha, WI: G. Leblanc Co., n.d.

Bowen, Glen H. Making and Adjusting

Clarinet Reeds. Hancock, MA: Sounds

of Woodwinds, 1980.

Guy, Larry. Selection, Adjustment and Care

of Single Reeds. Rivernote Press.

Kirck, George T. The Reedmate Reed Guide.

P.O.Box 1217, Westbrook, Maine

04092 Phone (207) 797-0857

Opperman, Kalmen. Handbook for Making

and Adjusting Single Reeds. Revised

Edition, M.Baron Company, Inc. 2003.

See also Brian Catchloves article and

bibliography in this issue.

Missed issues?

Corrections?

Address change?

PO Box 2188, Runcorn, Qld. 4113

enquiries@clarinet-saxophone.asn.au.

June 2003

13

You might also like

- Single Reed Reed Basics: Soak in WaterDocument4 pagesSingle Reed Reed Basics: Soak in Waterlorand88No ratings yet

- Adjusting Saxophone and Clarinet ReedsDocument9 pagesAdjusting Saxophone and Clarinet ReedsEngin Recepoğulları50% (2)

- Reed Saxophone ManualDocument2 pagesReed Saxophone ManualCamillo Grasso100% (1)

- Reed Adjusting PaperDocument41 pagesReed Adjusting PaperDiego Ronzio100% (2)

- Care and Maintenance of ReedsDocument13 pagesCare and Maintenance of ReedsCamillo Grasso100% (1)

- Clarinet Reed AdjustmentDocument6 pagesClarinet Reed AdjustmentJuan Sebastian Romero Albornoz100% (2)

- Saxophone and Clarinet Fundamentals PDFDocument31 pagesSaxophone and Clarinet Fundamentals PDFAlberto Gomez100% (1)

- Guide To Clarinet Reeds: Parts of The ReedDocument5 pagesGuide To Clarinet Reeds: Parts of The Reeddtcl bogusNo ratings yet

- Reed Adjustment PDFDocument6 pagesReed Adjustment PDFstefanaxe75% (4)

- Step by Step: Basics of Clarinet Technique in 100 StudiesFrom EverandStep by Step: Basics of Clarinet Technique in 100 StudiesRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Rico-Ultimate Tips For Saxophonists-Vol 2Document2 pagesRico-Ultimate Tips For Saxophonists-Vol 2chiameiNo ratings yet

- Clarinet EmbDocument4 pagesClarinet Embapi-217908378No ratings yet

- Basic Concepts and Strategies for the Developing SaxophonistFrom EverandBasic Concepts and Strategies for the Developing SaxophonistNo ratings yet

- Saxophone Secrets: 60 Performance Strategies for the Advanced SaxophonistFrom EverandSaxophone Secrets: 60 Performance Strategies for the Advanced SaxophonistRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (4)

- A methodical approach to learning and playing the historical clarinet. History, practical experience, fingering charts, daily exercises and studies, repertoire and literature guide. 2nd editionFrom EverandA methodical approach to learning and playing the historical clarinet. History, practical experience, fingering charts, daily exercises and studies, repertoire and literature guide. 2nd editionNo ratings yet

- Adjusting Clarinet ReedsDocument15 pagesAdjusting Clarinet Reedsapi-201119152100% (1)

- Art of Adjusting ReedsDocument44 pagesArt of Adjusting Reedsmadseven67% (3)

- Analysis of Tonguing and Blowing Actions During Clarinet PerformanceDocument12 pagesAnalysis of Tonguing and Blowing Actions During Clarinet PerformancePatercomunitasNo ratings yet

- Fit in 15 Minutes: Warm-ups and Essential Exercises for ClarinetFrom EverandFit in 15 Minutes: Warm-ups and Essential Exercises for ClarinetRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- Reed Adjustment ChartDocument2 pagesReed Adjustment ChartSumit SagaonkarNo ratings yet

- THE TEACHING OF SAXOPHONE OVER TIME: From Adolphe Sax to the present dayFrom EverandTHE TEACHING OF SAXOPHONE OVER TIME: From Adolphe Sax to the present dayNo ratings yet

- A Guide To The Art of Adjusting Saxophone Reeds 2Document12 pagesA Guide To The Art of Adjusting Saxophone Reeds 2louish91758410% (1)

- Tonguing ProperlyDocument5 pagesTonguing ProperlyAlejandro L Sanchez100% (1)

- The Science and Art of Saxophone Teaching: The Essential Saxophone ResourceFrom EverandThe Science and Art of Saxophone Teaching: The Essential Saxophone ResourceNo ratings yet

- The Devil's Horn: The Story of the Saxophone, from Noisy Novelty to King of CoolFrom EverandThe Devil's Horn: The Story of the Saxophone, from Noisy Novelty to King of CoolRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (3)

- Williamson Saxophone Pedagogy TipsDocument1 pageWilliamson Saxophone Pedagogy TipsJeremy WilliamsonNo ratings yet

- Circular Breathing: Meditations from a Musical LifeFrom EverandCircular Breathing: Meditations from a Musical LifeRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Building A Saxophone Techinique-Liley LearningDocument5 pagesBuilding A Saxophone Techinique-Liley Learningjimmywiggles100% (5)

- Perfect A Reed and BeyondDocument51 pagesPerfect A Reed and BeyondFearless_PIG100% (2)

- Early Clarinet PedagogyDocument2 pagesEarly Clarinet Pedagogyapi-199307272No ratings yet

- Clarinet Fundamentals 1: Sound and ArticulationFrom EverandClarinet Fundamentals 1: Sound and ArticulationRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- Joy of Music – Discoveries from the Schott Archives: Virtuoso and Entertaining Pieces for Clarinet and PianoFrom EverandJoy of Music – Discoveries from the Schott Archives: Virtuoso and Entertaining Pieces for Clarinet and PianoRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- The Saxophone MouthpieceDocument2 pagesThe Saxophone MouthpieceSumit Sagaonkar100% (3)

- Problems & Solutions Regarding Clarinet EmbouchureDocument5 pagesProblems & Solutions Regarding Clarinet Embouchureallison_gerber100% (1)

- Best of Clarinet Classics: 20 Famous Concert Pieces for Clarinet in Bb and PianoFrom EverandBest of Clarinet Classics: 20 Famous Concert Pieces for Clarinet in Bb and PianoRudolf MauzRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (5)

- Essentials of Clarinet Pedagogy The First Three Years The Embouchure and Tone ProductionDocument23 pagesEssentials of Clarinet Pedagogy The First Three Years The Embouchure and Tone ProductionFilipe Silva MoreiraNo ratings yet

- Saxophone and Clarinet FundamentalsDocument32 pagesSaxophone and Clarinet FundamentalsFraz McMannNo ratings yet

- Rose - Early Evolution Sax MouthpieceDocument14 pagesRose - Early Evolution Sax MouthpieceOlia ChornaNo ratings yet

- Clarinet Fundamentals 2: Systematic Fingering CourseFrom EverandClarinet Fundamentals 2: Systematic Fingering CourseRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (2)

- Bach for Saxophone: 3 Partitas - BWV 1002, BWV 1004, BWV 1006From EverandBach for Saxophone: 3 Partitas - BWV 1002, BWV 1004, BWV 1006Rating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (4)

- Module 2 ActivityDocument3 pagesModule 2 ActivityDhenver DimasacatNo ratings yet

- Themes in Chaucer's PoetryDocument4 pagesThemes in Chaucer's Poetryzohaibkhan6529No ratings yet

- Case Study Perception of A Teenager On PDocument42 pagesCase Study Perception of A Teenager On PRome Sapico PaleroNo ratings yet

- Um en Psi Modem GSM Eth 103965 en 00Document82 pagesUm en Psi Modem GSM Eth 103965 en 00migren8No ratings yet

- Critical Book Review (To Fulfill The Task of Course of Thermodynamics) Supporting Lecturer: Prof - Dr.Makmur Sirait, M.SiDocument18 pagesCritical Book Review (To Fulfill The Task of Course of Thermodynamics) Supporting Lecturer: Prof - Dr.Makmur Sirait, M.Siluni karlina manikNo ratings yet

- Spring Semester 2019 Final Exam Closed Notes: INSTRUCTOR: Marios MavridesDocument4 pagesSpring Semester 2019 Final Exam Closed Notes: INSTRUCTOR: Marios MavridesyandaveNo ratings yet

- Quantification of Caffeine Content in Coffee Bean, Pulp and Leaves From Wollega Zones of Ethiopia by High Performance Liquid ChromatographyDocument15 pagesQuantification of Caffeine Content in Coffee Bean, Pulp and Leaves From Wollega Zones of Ethiopia by High Performance Liquid ChromatographyAngels ValenciaNo ratings yet

- Non Accidental Injury in ChildrenDocument2 pagesNon Accidental Injury in ChildrenDoxo RubicinNo ratings yet

- Yeastar Product Slides PDFDocument91 pagesYeastar Product Slides PDFJeremyNo ratings yet

- Ibt Diagnostic TestDocument18 pagesIbt Diagnostic TestMoe Abdul HamidNo ratings yet

- Barimpala Kentucky Bluegrass (T-06)Document2 pagesBarimpala Kentucky Bluegrass (T-06)Nikola MilosevNo ratings yet

- طباعة معلومات الإقامة PDFDocument1 pageطباعة معلومات الإقامة PDFDaud AzadNo ratings yet

- ORACLe Backup PolicyDocument2 pagesORACLe Backup Policyyuva kumarNo ratings yet

- Vygotsky's Theory of CreativityDocument8 pagesVygotsky's Theory of CreativitywendychuiNo ratings yet

- P10557 PDFDocument7 pagesP10557 PDFpuhumightNo ratings yet

- Claudius Victor Spencer BiographyDocument71 pagesClaudius Victor Spencer BiographyLeena RogersNo ratings yet

- Amway CasestudyDocument11 pagesAmway CasestudyBecky Paul50% (4)

- Judicial Affidavit of Atty Dennis M. TimajoDocument9 pagesJudicial Affidavit of Atty Dennis M. TimajoMatthew WittNo ratings yet

- ALBÉNIZ, I. - Piano Music, Vol. 3 (González) - 6 Danzas Espanolas: 6 Pequenos Valses: 6 Mazurkas de SalonDocument10 pagesALBÉNIZ, I. - Piano Music, Vol. 3 (González) - 6 Danzas Espanolas: 6 Pequenos Valses: 6 Mazurkas de SalonFernando BarbosaNo ratings yet

- Smoke BombDocument8 pagesSmoke Bombkunjansingh431No ratings yet

- Chromatography 1 1Document49 pagesChromatography 1 1kelvinNo ratings yet

- Mackie The Miracle of Theism Arguments For and Against The Existence of God BM.11 - 199-216Document271 pagesMackie The Miracle of Theism Arguments For and Against The Existence of God BM.11 - 199-216jorrit w100% (2)

- BBG Anglais LV2Document11 pagesBBG Anglais LV2Anonymous QhB2OHxB0% (1)

- Consumer FinalDocument8 pagesConsumer FinalVivek 'Ruckus' MoreNo ratings yet

- Business ProcessDocument24 pagesBusiness ProcessTauseefAhmadNo ratings yet

- Organophosphate PoisoningDocument40 pagesOrganophosphate PoisoningMadhu Sudhan PandeyaNo ratings yet

- High School Admissions Training PresentationDocument58 pagesHigh School Admissions Training PresentationchimamandaokwuuwaNo ratings yet

- POTA RegulationsDocument16 pagesPOTA RegulationsJonas S. MsigalaNo ratings yet

- In Today's Lesson We Will ConsiderDocument46 pagesIn Today's Lesson We Will ConsiderLou Bagnall100% (1)

- FGFDocument11 pagesFGFWatan ChughNo ratings yet