Professional Documents

Culture Documents

(138-145) (Restricted Access) or The Open City

(138-145) (Restricted Access) or The Open City

Uploaded by

chroma110 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

18 views8 pagesKees Christiaanse on the open city.

Taken from Ilka & Andreas Ruby's book "urban transformations"

Original Title

(138-145) [Restricted Access]or the Open City

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentKees Christiaanse on the open city.

Taken from Ilka & Andreas Ruby's book "urban transformations"

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

18 views8 pages(138-145) (Restricted Access) or The Open City

(138-145) (Restricted Access) or The Open City

Uploaded by

chroma11Kees Christiaanse on the open city.

Taken from Ilka & Andreas Ruby's book "urban transformations"

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 8

{ Restricted Access }

or The Open City?

Kees Christiaanse

During a conference in Beijing in Octo-

ber 2006, environmental politics expert

Klaus Tépfer made a memorable state

ment: “The battle for a sustainable soci-

ety is won or lost in the city.” As the mo

ment draws near when two thirds of the

world population live in cities or at least

in an urbanized environment, it is clear

how urgent this statement has become.

The city is our center of culture, science,

politics, and trade. Various recent studies by social

scientists have made it clear that cities are the

breeding grounds of economic growth and innova:

tion. Apparently, density attracts density and leads

to intensive interaction. Intensi

turn, leads to innovative activities. Henri Lefeb:

e interaction, in

vre once described how the interaction between

various social networks leads to the eme1

‘of new networks. In Delirious New York, Rem

ence

Koolhaas writes about the Culture of Congestion

and the City of the Capti:

a compression of extreme expressions of culture

and life styles; in his book Creative Cities, Richard

Florida identifies the three T’s (Technology, Tal-

ent, and Tolerance) as the most important factors

lobe, which consists of

for the emergence of creative industries. All this.

that the high-density city is not just a

138

transitional phase in the development of human

settlements that would eventually be replaced by a

state of Arcadia, as Frank Lloyd Wright hoped for

in his book The Living City a

utopian project Broadacre City. The high-density

city must be regarded, now more than ever, as an

isualized in his

inevitable and constituting form of organization

of life on earth.

At the same time, the city also is the stage

upon which extreme energy consumption, pol-

lution, social abuse, and social conflicts have

‘emerged. In Beijing, for instance, the air quality

sometimes has become so bad that even radical

measures like the strict limitation of private car

use has had only negligible effects. The enormous

water consumption has lowered the groundwater

level to such an extent that the entire region now

wge and draughts, not to

‘mention impending geological problems. In Lagos

suffers from water sh

and other tropical mega-cities, the shortage of

Clean water and appropriate sewage systems and

the ubiquitous open garbage dumps have led to se-

rious threats to the public health and to an almost

irreversible pollution of the soil. In Sao Paulo and

me and

Johannesburg, excessive differences in inc

prosperity between social groups has resulted in

Cities that consist of archipelagos of gated islands

where the crime tate is sky high, Los Angeles is all

but paralyzed by its enormous suburban expansion

combined with the lack of adequate public trans-

portation,

Broaddore City was the antithesis ofa city and the apothe:

shaped through W

particular vision. Itwas both a pla

osis of the nevly born suburh he's

ing statemen

socio-political scheme by which each US. family would be

given done acre (4,000 m?) plot ofland from the federal

lands reserves, and a Weight-conceived community would

is. Ina sense it was the exact opposite

‘be built anew from

of transit oriented development. There isa train station

“The city isin debe to the surrounding coun-

try” says Topfer. “Te uses her natural resources and

the products of its cheap labor, and, in return, gives

back waste, erosion, and crime.” Of course, this

isa bit rhetorical: as part of the urbanized land-

scape, cityand country are complementary and

inseparably bound to one another in an ever more

complex relation. In Edge City, Joel Garreau points

cout that polycentric agglomerations form produc-

ers and peripheral

developments function complementary to each

other (ie., city dwellers go to the count:

recreation, and suburban duellers ¢

shop), and Saskia Sassen, in her book Global City,

esses the co-dependeney of urban agglon

tive organisms where local cei

tothe city to

tions and their global economy environments.

As faras the use of resources is concerned, we

are now faced with a paradox: the so-called devel-

oped world has arrived at a so-called sustainable

urban culture and a humane standard of comfort.

However, despite widely-applied sustainable tech-

nology, the growth of wealth has led to a steady

increase of energy-use, hence an increase in the

waste and carbon dioxide emissions. And although

the trend is digressive, a turning point, a significant

reduction of pollution, is nowhere in sight. On the

other hand, the so-called developing world lives in

so-called unsustainable way —ie., living without

sewer systems, the proliferation of refuse dumps,

and the burning of wood, ete. But on the whole,

the developing world uses only a fraction of the

and. few office and apartment buildings in Broudacre City

but the apartment dwellers are expected to be a small mi-

nority Allimportant transportation is done by automobile

and the pedestrian can exis safely only within the confines

lof the one acre (4,000 m?) plots where most ofthe popula-

energy produced, and the pollution generated per

persons in no way comparable.

Most people in the First World find it difficule

to re-adjust their consumer lifestyle with an eye to-

wards environmental responsibility, whereas most

people in the Third World want to live like people

in the First. The First World’s concerns about the

ecology of the Third World have been interpreted

as hypocritical and moralistic, This may partly

be true, but, of course, one of the motives of this

concerns the question whether the developing

nations may skip a few stages in the evolution

towards amore sustainable condition.

Development rests on cumulative acquisition

and management of knowledge, which results in

economic growth and technological innovation.

Apparently,

of trial and error, of consumptio

have to go through an evolution

id squander:

ing before we can sublimate our life into sustain-

ability. The efficiency and the effectiveness of the

‘combustion motor has more than doubled since

its invention. The Internet has become an indi.

pensable global communication instrument with

unprecedented positive effects. We owe it to the

American army, which developed it in order to

have an anti-hierarchic communication network

that would remain operational even if great parts of

it were destroyed by enemy attacks

The notion of rial and error has led some

people to believe that innovation can only prosper

under non-compulsory conditions. This has been

138

illustrated by the refusal of George Bush to sign the

Kyoto Protocol, arguing that reduction of global

warming will either be the result of technological

innovation under non-compulsory conditions or

the result of a shortage that will force us to act.

Arguing in this way, we need not worry about

the balance of energy in a city like Dubai. After the

invention of the refrigerator, after all, it should not

be too difficult to apply its principle to the heat of

the desert in order to transform the city into a well

ne heat

conditioned environment. Likewise, the s

could be used to turn seawater into fresh water, for

A carefully balanced interaction with nature, its

future golf courses in the de

resources, and the refuge from the city it provides.

however, requires self restraint

Sustainable City?

The word sustainable has been subject to in

tion and multiple interpretations and, therefore, it

is difficult to define precisely. In view of its topi-

cality and its global acceptance, however, we are

obliged to use it:

Inurban planning, if we ask ourselves, What

nes a sustainable city? we realize quickly that

ithas become a very complex question, given that

ge

as well as social, cultural, and economic influences

character

aphical and structural aspects of urban form

can have a sustainable influence comparable to

that of applying sustainable technology. In Tokyo,

140

for instance, the limited number of square meters

buile per person and the low percentage of car

gical footprint con-

siderably when compared to Western agglome:

ownership has reduced its eco

tions with a similar size of population. Its size and

structure make it difficult to cross Tokyo by cat:

Car ownership is only allowed if one has a parking

space, which, in turn, is hard to come by and some

times as expensive as an apartment (which is hardly

bigger than a parking space). Public transpor

is highly developed and ubiquitous and, therefore,

tion

int of

‘one may assume that an average inhabi

‘Tokyo lives rather sustainably as far as pressure on

public space and mobility are concerned,

eis plausible that influencing the form of the

city influences social behavior —hence, an enor

‘mous potential is created for what we call social

sustainability. The efficient use of public space

which helps to keep the urban footprint compact,

can lead to various advantages. Higher density can

stimulate the pedestrian traffic and use of public

transportation, thus encouraging social interaction

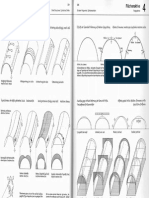

Fig 1 Left: The city turns into islands of spatial, functional

and social difference, connected by single access, Right: A

network allows

multi-directional, anti-hierarchical, sti

foran open system in which diverse communities can settle

and interact.

which, in turn, leads to economic growth and in-

novation. Density can also reduce the size of tech-

nical infrastructures like roads, pipes, and cables

~and, thus, save energy.

A socially sustainable city encourages combina-

tions of functions, which allows city distriets to be

largely self-sufficient. Local in

sustenance within walking distance, which has a

ants find their

positive effect on mobility: The key to a socially

sustainable city, however, is the network of public

spaces, Ie forms the underlying structure on which

social interaction, activation, combination of func-

tions, density, and transformation can develop in an

open exchange, which allows us to speak of an open

city?

The Open C

In the roth-century city, public space—the

network of streets and squares —was the place of

both communicating information and transporting

goods. Many r9th-century city districts still look

the same, but their role and social meaning have

radically changed. The physical and social cities

have been torn apart. In the minds of the people,

there are multiple social networks which stretch

across physical and virtual distances, but which do

not necessarily have any connection with the place

where they find themselves at that moment

‘These urban quarters—be it Greenwich Village

in New York, Prenzlauer Berg in Berlin, Qud-Zuid

The authors concept of open city differs From the already

i

Open c

existing definitions of such, See

ikipediaorg/witi

ives equal access and status to inhabitants and visitors of

allfaiths, races,

Open. City %28disambiguation

nd nationalities; as opposed to a city that

is declared demilitarized dusing a war, thus entitled to im

‘munity from attack under international lav;

in Amsterdam or Besiktash in Istanbul — have

the great capacity of adapting and assimilating to

changing circumstances. Apart from the building

typology and the principles of allocation, ic, city

planning, this is mainly due to the open, multiple

and non-hierarchical street pattern, which is why

we can speak of an open cit

This city has developed more or less by itself

as people are in principle free to move, settle, and

live; they are protected by a

equal rights. Rather than the development of the

proverbial melting pot of the Open City, an entropic

soup of everything mixed together, instead it is

an organism of concentrations of social groups

and functional differentiations, an archipelago

of social and urb

city bas emerged through the interaction, cross

stem of justice and

islands. The notion of open

fertilization, and friction among these groups and

networks, which creates urban cultures

Fig. 2 Left: Until 850, a

space: the living city was to 1 with the physical cigy

interaction took place in public

Right: Today people mo

the same purpose (Fi, Finshopping), in virtual

‘with their social networks. How dreadful this

ns, ia compliment for the adaptability ofthe city to

from mall to mallas types fol

lox

141

For instance, although a Chinatown within an

occidental city is a concentrated, closed commu

nity, at the same time, it has opened its doors for

others through commerce and gastronomy in its

street facades. It has no fixed borders but overlaps

and interacts with other communities that settle

‘within the open system.

‘The Open City is not a stable, but a dynamic

state, a temporary equilibrium between openness

ind reticence and based on tolerance. In that sense,

he Open City can also occur locally in an agglom

eration. This temporary equilibrium makes the

Open City vulnerable because its existence has been

threatened by its own mechanisms, for instance

by the mono-functional concentration ofa like-

minded middle class ina suburban enclave

‘The City as a'Trec

‘The Open City is threatened by its own mecha-

nisms of tolerance and voluntary closed-ness, in

short, by its own freedom. These mechanisms

stimulate the emergence of enclaves with separate

functions at great distances from each other with

mensional connectivity, In 1965, in

City Is Not a Tree, Christopher Alex

his article

ander pointed this out, at atime when itwas still

widely believed that Modernism would have an

unequivocal beneficial effect on the city:

In some city centers, despite the physical

robustness of the old urban structure, entire blocks

142

have become privatized compounds that have been

increasingly interconnected beyond the pu

realm and form a second network with restricte

access. A good example is the map of the original

street pattern and the growth of the network of

lifted pedestrian passages between shopping malls

in the center of Houston, found in the book Lad:

ders by Albert Pope. The emergence of such con-

ronments also happens invisibly like in

the area around Times Square in New York, which

seems to be part of an open city, but in reality itis an

area that is completely managed and controlled by

trolled en

Disney

The present day segregation and isolation of ur

ban districts is partly due to the development of in-

dividual transportation. Through the development

of differentiations and hierarchies into pedestrian

zones, main-streets, and motorways with one-

dimensional connectivity, the city changes into an

archipelago of urban islands with few connections,

and, thus, with lower communication potential

Fig, 3: Analysis of tre like road network and related built

developmentin Zurich North.

‘The open network has been changed into trees and

branches (irees according to Alexander or ladders

according to Pope), where traffic flows are always

connected to the main branches, Together with the

jump in speed and radius that modern transporta-

tion systems have caused, this development is re-

it that today we live in another

city, in which itis difficult to create a qualitative

and coherent and communicative system of inter-

connected public space — where tolerance has been

sponsible for the

replaced by tension or even conflict and where

physical and social barriers dominate.

Allover the world, this new species of city,

an archipelago of tree- and ladder shaped access

routes to which cling island-shaped suburbs, cam-

puses, gated communities, shopping malls and

business parcs, is developing according to the same

principles, and, therefore, it constitutes a Global

City counter-model to Saskia Sassen's Global City

Sassen’s Global City isa specific, characteristic,

historic, closed metropole which attracts global

actors. The counter-model Global City is the exact

opposite: generic, non-descript, a-historic urban-

ized landscapes, which attract local actors.

Ifwe look at Greenworld in Shanghai,

Leidschenrijn in Utrecht, Goktiirk in Istanbul, Sea

Side in Florida or even a Jewish Settlement on the

western bank of the river Jordan near Jerusalem,

we notice that they are made up of the same in-

gredients, as ifan arrangement of LEGO building

blocks which can be combined at will. Tt appears to.

o

Deal

be atwo dimensional hyper-arrangement of standard

clements: highway exits, gas stations, private resi-

dences with garages, shopping malls, sports facili

ties, business parks, school campuses, and wellness

centers,

IfJerusale:

hermetically closed compounds where strangers

Sea Side, and Greenworld are

are not welcome, in Leidschensijn there are streets

Fig. 4: The original street pattern of Houston is overwrit

tenby a covered pedestrian network of interconnected,

malls on the first floor level

Fig. 5: Lefts The cluster of the medical faculty in the heart

‘of Rotterdam slowly turns into a compound of limited

access, Right: Times Square today as an “invisible” gated

compound, programmed by Disney

143

which are gradually developing into ethnic com-

munities, ust like the Chinatown in the old city

And in the suburb Géktiirk near Istanbul, informal

settlements ofimmigrants from Fastern Turkey

have formed a complementary symbiosis with the

gated communities. The space between the gates

around the residential areas has been filled up by

‘gececondos, yap-sat apartments, and shops, which

has [ed to active street life and small-scale services

within walking distance. The last two develop:

ncouraging because they show that

urban re-animation is also possible in the suburbs.

‘ments are

Hope

Does this mean that the Open City has reached

the end of its existence? In Europe, the city was

entirely surrounded by walls until the beginning of

the 19th century. After that, the walls were broken

down and the city opened itself, Will the city close

again by the year 2080? Will our great-grandchil-

dren tell their children that there was a period

between 1820 and 2080 when the city was open?

As we have seen, the Open City is not acity but

acondition—a dynamic equilibrium between open’

and closed, and the physical reflection of our social

conditions. In this respect, it has become urgent

that we investigate the conditions constituting the

vulnerable equilibrium of the Open City: Which

kinds of urban structures support the Open City?

Can we stimulate Open Gity forms by pro

‘Gececondos

nts buile without regard to consteuction st

*Yapsat”is a Turkish expression that literally means “do

isa Turkish expression for “high-rise

apart dards.

1h6

intervention with design and process management?

Today, the most urgent task for urban planners

is to safeguard the structures of public space and

connectivity that negotiate between the open and

the closed and encourage the communication be-

tween them, aswell as to implant urban catalysts,

that is, local projects which have a positive initiat

ng effect on their surroundings

If the Open City can be seen as a positive

equilibria

then luckily this still exists in many places, for

between uniting and separating forces,

instance, in former harbors and industrial areas.

The Bilgi University in Istanbul, for instance, was

founded by two young Turks who had studied

abroad and recognized the need to stimulate hig

q

tality education and research. They sold their

eds to

essful ICT company and used the proc

found the Bilgi University, which in just five years

has developed into an institution with seven facul-

ties and more than 7,000 students and connections:

‘with famous foreign universities, The first housing,

accommodations were created by renovating a for

mer school building in an old city district and ever

since, the same housing strategy was consciously

adopted forits expansion. Today, the university

‘owns several units all over the city, which form a

network of decentralized clusters that stimulate

the development of the surrounding city districts.

Their most recent and most ambitious project

Sentral, consists of the redevelopment of an old

electricity plant on the peninsula where the Gold

en Horn marks the space where two small rivers

flow together. This project (in its size and program)

is comparable to Zeche Zollverein in Essen, Ger

many: it consists of a big park which is open for the

public by day and apart from faculties, laboratories,

and student halls in and around the transformed

factory buildings, a Museum of Modern Art has

been built for some 50 million dollars. The campus

}ous urban catalyst for its envi-

has become an enor

ronment. Not only has a unique cultural park on

the tip of the Golden Horn been realized, but the

presence of the campus stimulates a self-gencrating,

urban renewal in the surrounding districts.

In Harbor City in Hamburg, for which we de-

signed the master plan and the public space in the

form of streets, courts, docks, plazas, bridges, abut-

ments, parks, and harbor basins to form a sensitive

network —all in all, defining the scale, orientation,

and communication with the city. In spite of the

tempestuous and partly uncontrolled developments

of Harbor City, this network has survived thus far

and has proven to be an intelligent blueprint where

various programmatic and architectural initiatives

have taken root and can engage in a dialogue with

their environment. It goes without saying that a

‘master plan of such magnitude in the middle of

the city has been subject to a multitude of forces:

politics, planning authorities, project development,

investors, judges of design competitions, general

complaints from the populace, and economic fluc-

tuations. These forces come into play in different

degrees against or with each other, which also puts

the cohesion of the master plan to the ultimate

test. During the realization of the project, it turned

out that the master plan was much more flexible

and adaptable than expected, leading to a diversity

and heterogeneity which has only yielded positive

effects, thus far

The stakeholders’ consensus about its basic

qualities has also made sure that the identity of the

plan as a coherent organism has been maintained,

even without much unity in the design. By and by, a

city district is emerging where the network of public

spaces has become the basis of negotiation between

architectural styles, programs, and activities within

the plan. Thereby, the ground plan of Harbor City

has acquired a stratification through negotiation,

replacement, and the revision of rejected concepts,

which one might call its urdwn memory.

Due to the speed of its development, Harbor

City will continue to be built up over the next 15

years, but even before that it will have started on

process of revision and change through replace-

‘ment or adaptation of buildings and structures,

which will feed its urban memory. The ground plan

of Rome has a memory, a palimpsest, in which its

history is recorded. Harbor City will show that we

can initiate such a memory for a new project as a

and this

rather

basis for creating an Open

than designing, may well be the architect's most

SK

important

1465

You might also like

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (844)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5810)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1092)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (348)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Architecture and Modernity A CritiqueDocument278 pagesArchitecture and Modernity A Critiquealecz_doro100% (13)

- Fumihiko Maki Nurturing Dreams Collecte PDFDocument292 pagesFumihiko Maki Nurturing Dreams Collecte PDFchroma11No ratings yet

- Transport and Urban DevelopmentDocument305 pagesTransport and Urban Developmenttungstentee100% (5)

- Private Cities-Global and Local PerspectivesDocument255 pagesPrivate Cities-Global and Local Perspectiveschroma11No ratings yet

- Financing Sustainable Urban Development in LDCsDocument172 pagesFinancing Sustainable Urban Development in LDCschroma11No ratings yet

- Concept Design Games: N. John Habraken and Mark D. GrossDocument9 pagesConcept Design Games: N. John Habraken and Mark D. Grosschroma11No ratings yet

- Jacobs Great StreetsDocument16 pagesJacobs Great Streetschroma1150% (4)

- Estructura ActivaDocument16 pagesEstructura ActivaMagister Architectura Tec VizcayaNo ratings yet

- Design For FlexibilityDocument8 pagesDesign For Flexibilitychroma11No ratings yet

- Catalog 5 IABR enDocument226 pagesCatalog 5 IABR enchroma11No ratings yet

- Lenferink Samsura RSA 28-4Document15 pagesLenferink Samsura RSA 28-4chroma11No ratings yet