Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Excerpt From Cooked Up: Food Fiction From Around The World

Uploaded by

SA BooksOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Excerpt From Cooked Up: Food Fiction From Around The World

Uploaded by

SA BooksCopyright:

Available Formats

Celebrating this universal experience, Cooked Up, compiled by Elaine

Chiew, draws together authors from all over the world, each bringing

to the table a unique literary interpretation of the food theme.

These are mere glimpses into the rich variety of short stories (including

flash fiction) contained in this book a veritable treat for the senses

and an uplifting cross-cultural reading experience.

FICTION

CookedUpCoverJS.indd 1

UK 9.99 US $16.95

New Internationalist

New Internationalist

newint.org

Food fiction from around the World

A young man attempts to avoid military service by over-eating...

a woman re-enacts her husbands infidelities with fish bones...

students at a cookery school war over woks... a food bank visitor

gets more than she bargained for meals are prepared and

shared from Cambodia to an Indian kitchen in the US, from Russia

to war-torn Croatia.

Cooked Up

Food is our common ground, bringing together families, communities

and cultures. How we cook and eat can tell us a lot about ourselves.

Food can evoke memories good and bad; can be symbolic of where

we come from or where we want to be.

Cooked Up

Food fiction from around the World

Elaine Chiew Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni

Rachel Fenton Diana Ferraro Vanessa Gebbie

Pippa Goldschmidt Sue Guiney Patrick Holland

Roy Kesey Charles Lambert Krys Lee

Stefani Nellen Mukoma Wa Ngugi Ben Okri

Susannah Rickards Nikesh Shukla

New Internationalist

16/12/2014 11:39

Mukoma Wa Ngugi

Walking the Wok

When my friend Daniel Chan confided in me that Jennifer

was leaving him because he was washing his wok with soap,

I laughed till I started to wheeze.

And when I came up for air it was to use the little

psychology I knew to assure him he was obviously displacing.

Jennifer could have left him for any number of reasons he

was too short, had a missing front tooth, and even though

only in his mid-twenties, was already balding. To his credit

he was an excellent chef, but he was considered a bit eccentric

because he exercised, which is to say he ran a mile every other

day. To all this Chan promptly responded, Fuck off.

The more I thought about it, the more improbable it

seemed that in a culinary school in a small town in Kenya

called Limuru, a soap-washed but clean-rinsed wok could

come between two lovers from China, and leave the man

ostracized from both his community and his adopted society.

It was not just Jennifer, Chan explained: his fellow Chinese

students were no longer talking to him, and African students

were eyeing him with suspicion, sometimes jeeringly and

sometimes sucking air between the teeth to voice the jeer.

A few days after Chans half-confession, half-lament, the

culinary students, chanting a few choice slogans like Fry

Chan and Walk the Wok went on strike. The riot police,

never having been called to this part of town to quell a strike

by culinary students, got lost, giving the students enough

time to raze Chans dormitory to the ground. We were all

sent home for two weeks.

131

Mukoma Wa Ngugi

vvv

Mpishi Msanii College (which aptly translates as The Artist

Chef) rested in the outskirts of Limuru, on land donated to

the colonial government in the 1940s by Lord Baring, and

inherited by the African government in the 1960s. Lord Baring

carved the 10 acres from his 2,000-acre ranch, declaring that

Africa needed Africans with practical minds and practical

skills, like cooking.

So started the Lord Baring Native Cooking School, where

graduating from the three-month course in British etiquette

and cuisine assured students of work in country clubs and

the homes of various wealthy colonials.

With the wave of nationalization and renaming that came

with independence, or still-in-dependence as the witty

amongst the natives called it, Mpishi Msanii College was

born. The three-month course in cooking pancakes, fried

sausages, eggs and chips and broiled rabbit grew wings,

becoming an intensive two-year program that produced not

cooks, but cosmopolitan chefs well versed in local and global

cuisines.

The one thing that remained unchanged was a survival

course where each student was escorted blindfolded to the

middle of Ngong Forest and left there with a box of matches,

a machete and a Polaroid camera. The idea was to eat well

and efficiently no matter the circumstances. Some had

returned with Polaroids of wild boar, snake, hare and other

small game, served on plates made out of twigs and leaves. I,

for one, had quickly pounced on a baby deer which I roasted

to a perfect tenderness over a dry fig-wood fire. Mercifully,

and for no good reason beyond luck, no-one had ever died in

this rite of passage.

With that kind of dedication to student learning, Mpishi

Msanii College soon became one of the top culinary schools

in Kenya. Through tourists who ate in the five-star, big-city

restaurants that graduates worked in, the schools fame grew,

132

COOKED UP

attracting dedicated teacher-chefs and eager students from all

over the world. The student population comprised daughters

and sons of wealthy Africans who had failed to make the

grades necessary to get into their national universities and

had scaled down their dreams to become cynical and reluctant

chefs; Africans who really wanted to become chefs I would

like to believe that I fell into this group, even though I had

failed my university entrance exams and foreign students

from all over the world.

We assumed this last group to be rich, because they seemed

to have the best of everything personalized spatulas,

graters with fancy monograms, and silicon mixing bowls.

But it could be that one dollar when converted into a Kenyan

shilling was enough to buy you a Tusker beer, three loaves of

bread, a pack of cigarettes and some Big G bubble gum.

Students of each nationality naturally coalesced into

gangs, and Mpishi Msanii College was home to drunken

midnight cooking competitions that often ended in violence,

with singed hair and burns from boiling water and hot

oil. In this underground world, sabotage attempts ranging

from unscrewing salt-shakers to mixing a rotten egg in

the other groups flour mix were constant. But during the

day, dressed in our white coats, bandaged arms carefully

out of sight, singed hair tucked under our brimming white

chef hats, administrators and teacher-chefs would not have

sensed any discord.

Chan was a much better chef than I he had an

imagination that allowed him to combine disparate spices or

foods, as if he could mix and taste them in his head before

adding them to his pan. It was he who suggested adding a

light touch of curry, crushed garlic and black pepper to an

onion, mushroom, green and red pepper omelet. But, even

more innovative, he added eggplant. Biting into it while still

hot and juicy was like biting into different textures of spicy

tastes milky and crunchy all at once.

133

Mukoma Wa Ngugi

His advanced skills as a chef, combined with gang loyalty

he belonged to the Chinese gang and I to the Kenyan gang

(which further sub-divided along ethnic lines unless facing

the foreigners) made our friendship improbable. But after

we ran into each other a few times at a den where the potent,

illicit brew Changaa was sold, we became fast friends.

In the den, no-one spoke English, so often the laborers

from nearby coffee plantations communicated with Chan

through hand-gestures and drunken nods. The end result was

that mutual curiosities, most of them pertaining to culture

and sexual prowess, went unanswered until I came along to

translate, earning myself an occasional free glass of Changaa,

as well as Chans trust and friendship.

Chan liked to unbutton his shirt and lie down on the

bench when there were only a few customers visiting, light

a cigarette and start asking questions, sometime regaling

us with stories of his own like how his parents were former

schoolteachers who lost their jobs during Maos Cultural

Revolution. Western tailored suits and dresses were found

in their attic. So he grew up poor, surviving mostly on rice.

But the more he thought about it, the more he realized he did

not have to eat plain rice he could add spices to it, spices

gathered from leaves and tree barks.

Always remember, necessity is the mother spice, he

declared as he waved a finger at his spellbound audience.

And so his rice became a gourmet meal until one day he

added poisonous bark and he had diarrhea for days. It was

then that he resolved to become a chef and turn his love into

a more forgiving science.

One memorable night Chan pulled a bottle of Coke from

his pocket and added a few drops to his glass of changaa,

getting rid of the brews bitter aftertaste. From then on, if you

wanted a touch of rum at an extra cost of one shilling, you

asked for the Chan Cham Rum.

The proprietor of the den, Madame, also had a running

134

COOKED UP

special, 10 shillings for a glass of cham, as we grew to call

the drink, and a small packet of githeri rolled in newspaper.

Githeri was a popular local dish boiled maize and beans

spiced with a bit of salt. But one day Chan drunkenly

observed, and I drunkenly translated, that githeri was the

most boring and unimaginative meal he had ever had the

misfortune of eating. As the clientele worked themselves into

a rage over the perceived insult, Madame challenged Chan to

improve the githeri, or the curse of our ancestors, who had

survived sieges, famines and droughts on this dish, would

fall upon him.

Chan asked for a flashlight, and ten minutes later, he

was back with an assortment of barks, leaves and grasses.

He ground everything into a thick paste, and tossed a pan

onto the cooking fire. He added a healthy helping of Kimbo

cooking fat and let the onions brown, adding the paste and

eventually the githeri. Chan earned everyones respect that

night. I suppose the survival course did come in handy.

vvv

Our Master Chef, an old Kenyan man who it was rumored

had been Lord Barings chef, instructed us through a mixture

of invectives and wise sayings like Do not play God,

Humility comes before the knife and fork, and his favorite,

To cook is to travel through cultures. So in our cooking lab

and white aprons we had traveled to France, Turkey, Japan

and Western Africa.

We had stopped by India where Master Chef started the

journey by saying: Indian food is like jazz, coconut milk is

the drumbeat, turmeric the bass, cloves the trumpet but

curry, he paused, looking up in the air in search of the right

words Curry is fools gold.

But it was while in mainland China that the troubles

started. There were three commandments that had to be

followed at all costs, Master Chef declared. Love your wok.

135

Mukoma Wa Ngugi

Never wash your wok with soap. And oil your wok after each

use. We learned how to season the wok by roasting it over

open flames for an hour, sponging it with oil, then letting

it cool. We rubbed salt and black pepper over the surface,

and then fried sesame seeds. Soon, the smoke, sweet and

light with hints of stir-fry, filled the room. I watched my

wok transform from a glossy, buy-me-I-am-new shine to

a black, leathery, sandpaper gloss. After several hours of

seasoning our woks, we left them sitting on the counter to

cool overnight.

The following afternoon, after a morning spent with

Master Chef lamenting how nobody takes Chinese breakfast

food seriously because of the invention of white bread,

we made our first stir-fry dish. Nothing heavy, a little bit

of sesame oil, two tablespoons of oyster sauce, soy sauce,

minced garlic, onion, bok choy, carrots and broccoli poured

over short-grain white rice. It tasted good, but not unusually

good seasoning the wok didnt seem to make a difference.

We rinsed the woks with cold water, dried them with paper

towels, oiled them again and started the seasoning process

all over.

Then at the end of the week it happened and I understood

what Master Chef meant when he said that the wok, like

language, is also a keeper of culture. We prepared a simple

broccoli-based meal, yet it contained hints of past meals, rich

enough to be noticed, but calm so as not to overwhelm the

present taste. It was the old giving way to the new, or rather

the new recognizing its past, the original sauce still present

like an active ghost in the new sauce I had just made. Later

that evening while at Madames, it occurred to me that if we

could cook history, it would have to be with a wok.

I remember seeing Chans wok in class oil sizzling in a

bottom so discolored that it was metallic, the edges a thin

light blue that got darker closer to the top, the dark brown

wooden handle split from overuse. It was utterly unlike my

136

COOKED UP

wok, which had a spongy, even sooty inner surface. Chan was

clearly washing his wok in soapy water and, whats more,

scrubbing it clean with steel wool. Master Chef was pacing

up and down, agitated, shouting The Past is Prologue, To

love your wok is to let culture grow, It must have history

as he tried to correct Chan by reprimanding the whole class.

Still, I didnt foresee that Chans actions would later tear

the whole school apart.

vvv

When school reopened after the fire and we returned to a

brand new dormitory courtesy of the Chinese Consulate

in Nairobi, the first person I sought out was Chans exgirlfriend. Jennifer, though Chinese, spoke English with a

British accent. She was beautiful and clearly rich, but she

had some bohemian tendencies she liked to wear torn jeans

with beat-up white tennis shoes that during the rainy season

kept slipping off her feet and getting stuck in the mud, and

she liked to wear her long hair in a bun held in place with

two chopsticks. I had an inactive crush on her.

The wok changed Chan, she said when I asked her why

they had broken up.

The wok changed Chan? I repeated in surprise.

When he started cleaning it, he started forgetting his

culture. And I loved him because he was home for me, she

answered in a tone that suggested I understood what she

meant. I did not.

You really left him because of a wok? I thought I might as

well get to the bottom of it.

How can a Chinese woman be with a man who washes his

wok? She asked with a self-conscious smile.

I started to say something else but she stopped me.

I still love him, she said in a whisper. But he has to stop.

You are either Chinese or you are not, she added as she

stretched a long thin arm out of an oversized rainbow-colored

137

Mukoma Wa Ngugi

sweater to squeeze my hand. I felt my heart flutter. It was

time to go before I started misreading things.

I was starting to understand. A wok in Kenya was no

longer just a wok; it was about finding mojo in a place where

you were different. Chan was just not being reflexive and

defensive enough. In his ability to synthesize and create, in

his fluidity, he was unbalancing everyone else.

vvv

After I left Jennifer, I walked through the famous Limuru

fog to come across a group of Chinese students smoking

up a storm of Marlboros behind the cooking lab. I had quit

smoking a few years before but I had to find a subtle way in.

Sco? I asked. Kenyan lingua franca demanded that I ask

for a sco, short for a score.

Inevitably I followed this up with Can I have some fire

too? Damn to be out of smoke and fire. The laughter

that followed, at once a chorus of different pitched coughs,

some low, some high, let me know I was in. Besides, this was

an opportunity for them to disabuse me of my friendship

with Chan.

The strike I started saying.

Its all about our culture, man. We are in the belly of

the beast Babylon never let dread-man grow. It was a

joke because everyone laughed at me I assumed but,

nevertheless, it was funny and I too joined in.

Culture I prompted when our laughter died down.

We are Chinese in Africa we are the ambassadors, said

a woman masked by the smoke and fog.

But Chan, he is one of you, I responded, sucking on the

cigarette and thinking of the impending re-addiction might

as well make it count.

He want to fuck the wok, instead of walking the wok, an

anonymous voice said, to more laughter.

Look, a more serious voice said, we are here, we eat your

138

COOKED UP

food, we drink your beer, we are here. But how can we really

know we are here?

But look, people, the wok, its not even Chinese everyone

in Asia uses a wok

Someone slapped the sco from my hand and slowly ground

it to its death.

In Africa, the wok is Chinese, a voice said, sounding

dangerous. It was time to wade some more in the fog. I had

one more stop.

vvv

At Mpishi College, there was only one place to find a

concentration of Kenyans and Africans. In spite of everything

we had learned about cooking, nutrients, dishes from faraway lands, African culinary students could always be found

at Wakari Nyama choma where, the owner claimed, roast

meat was an art. Take the African sausage, goat tripe filled

with all sorts of goodies he had a point.

So as soon as I walked in I knew what I had to do order

one kilo of the sausage and two kilos of nyama choma

rubbed with curry but just enough so that it was a hint to be

overpowered with fresh garlic and minced cilantro. The only

question I really had to answer was this: how the hell was I

going to give up this delicacy for information?

Look, man, Chan thinks he can come to Africa and do

whatever the fuck he wants. He is messing with our culture.

He drinks changaa and messes with githeri. Look, you dont

see me adding boiled maize and beans to broccoli, someone

summarized between mouthfuls of the nyama choma.

This is what it boils down to, I reasoned to myself: Jennifer

wanted Chan because he keeps her authentically Chinese, the

Chinese students want Chinese cuisine and traditions protected

and Africans do not want foreigners to mess with their cuisine and

traditions. In this collusion of interests, a strike was inevitable.

But what did Chan want?

139

Mukoma Wa Ngugi

vvv

When I told Chan that Jennifer would take him back if

he stopped washing his wok, his reply was to suggest we

celebrate our return by visiting Madame.

After we were nicely drunk and he lay peacefully on a

wooden bench, I asked him why he washed his wok, and

with soap, when all his troubles could end simply by wiping

it clean. He did not say anything; he just lay on that bench

rubbing his belly like it was a genie bottle. Then he abruptly

ordered me to follow him to the cooking lab.

This, this will be something nobody has ever tasted

before, not even I, he said as he threw fat salmon skin into his

wok which he let fry until there was a nice ring of oil at the

bottom. I knew that was going to be in place of oyster sauce.

He skimmed off the now dry skin and scales and added

some garlic powder, paprika, crushed red chilies and diced

white onions to the oil. He turned up the flame and once the

sizzle started, he turned it down to sweeten the onion until

the sauce produced a musky sweet smell. He added some

fresh basil and dashed some soy sauce into the wok. The

sweet smell soon became a furious storm of clashing tastes,

bubbling dangerously like hot molten lava.

Chans movements were deliberate and steady like he was

keeping to the rhythm created by his hands and the fire. He

took some old rice and precooked lentils from the fridge and

started heating them in a pan. He added some raisins before

turning his attention back to the wok and the sauce, to which

he added peanuts and broccoli. When the peanuts started to

brown, he took them out and threw in shitake mushrooms.

Three minutes more and dinner was ready.

The food was a symphony of tastes, at once impossible

yet possible. The lentils fought the rice and raisins, and the

sweet onions tried to rise above the hotness of the crushed

red chilies, the oil from the salmon swarmed against the

peanut oil. The shitake mushrooms, cooked on the outside,

140

COOKED UP

but steamed in the inside, had a taste that did not exist in

my world until then a slippery crunch that gave way to the

softest of bites, and the broccoli, soft on the outside, was still

juicy and crunchy on the inside.

On my animated tongue the food was a galaxy of tastes,

each distinct and without the heaviness of the past that

infused the food we had been cooking. Put simply, it was as

god, or perhaps the devil, intended food to taste: naked and

in the present.

As we ate, or rather as I listened to what I was eating

and Chan the artist observed his audience of one, he tried

explaining. The soil in which things grow, that is the real wok.

I didnt understand and chalked it up to still drunken talk.

You know they will ask you to stop, I said as I washed

his wok with soap and hot water. He did not have to answer.

I knew why he would never stop. And he would never give

this up for Jennifer.

I understood. My eyes were open and I was feeling lighter

already. I too wanted to make dishes that were not prisoners

of the past. Right was on Chans side and as in a revolution,

we would win more and more people to our side one

liberated mouth at a time. And if we failed and were kicked

out of the school, so be it.

We had tasted the future.

Time to go back to Madames, Chan said as soon as I had

dried his wok on an open flame and oiled it with more of the

salmon skin. n

141

You might also like

- Jikoni: Proudly Inauthentic Recipes from an Immigrant KitchenFrom EverandJikoni: Proudly Inauthentic Recipes from an Immigrant KitchenRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- 2018-05-17 Re1 (Old Format) TheDock Food Menu-ETC PageDocument24 pages2018-05-17 Re1 (Old Format) TheDock Food Menu-ETC PageThammachart SeafoodNo ratings yet

- T3 India April 2018 Issue Features Cutting-Edge Tech Like Modular SmartwatchDocument100 pagesT3 India April 2018 Issue Features Cutting-Edge Tech Like Modular SmartwatchTushar WaliaNo ratings yet

- Billy Bibliotheque AA 982683 8 PubDocument16 pagesBilly Bibliotheque AA 982683 8 PubcelinelbNo ratings yet

- Finding His Path: The Other Side of Datuk Seri Bernard ChandranDocument20 pagesFinding His Path: The Other Side of Datuk Seri Bernard ChandranAmsyar muhrizNo ratings yet

- Flavour Magazine - October 2010-TVDocument68 pagesFlavour Magazine - October 2010-TVRadu IlcuNo ratings yet

- Gautier Office AnglaisGB BdefDocument84 pagesGautier Office AnglaisGB Bdefteam37100% (1)

- A Culinary Tour of Classic British CuisineDocument128 pagesA Culinary Tour of Classic British CuisineMoe FuzzNo ratings yet

- Murdoch Books London Book Fair 2017 Rights GuideDocument112 pagesMurdoch Books London Book Fair 2017 Rights GuideAllen & Unwin0% (1)

- Fall 2021 Hardie Grant CatalogDocument87 pagesFall 2021 Hardie Grant CatalogChronicleBooksNo ratings yet

- Catalogue UK +MICHELIN COMPET+CLIENTDocument78 pagesCatalogue UK +MICHELIN COMPET+CLIENTtheo VINo ratings yet

- Travel Leisure Southeast Asia Magazine April 2018Document108 pagesTravel Leisure Southeast Asia Magazine April 2018PS GuptaNo ratings yet

- Airasia Magazine August 2013Document164 pagesAirasia Magazine August 2013SangrealXNo ratings yet

- A Taste of Cowboy: Ranch Recipes and Tales from the TrailFrom EverandA Taste of Cowboy: Ranch Recipes and Tales from the TrailRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (3)

- Service Included: Four-Star Secrets of an Eavesdropping WaiterFrom EverandService Included: Four-Star Secrets of an Eavesdropping WaiterRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (176)

- Chefs & Company: 75 Top Chefs Share More Than 180 Recipes To Wow Last-Minute GuestsFrom EverandChefs & Company: 75 Top Chefs Share More Than 180 Recipes To Wow Last-Minute GuestsNo ratings yet

- Under the Table: Saucy Tales from Culinary SchoolFrom EverandUnder the Table: Saucy Tales from Culinary SchoolRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (35)

- F*ck, That's Delicious: An Annotated Guide to Eating WellFrom EverandF*ck, That's Delicious: An Annotated Guide to Eating WellRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (3)

- Love in Any Language: A Memoir of a Cross-cultural MarriageFrom EverandLove in Any Language: A Memoir of a Cross-cultural MarriageNo ratings yet

- White Jacket Required: A Culinary Coming-of-Age StoryFrom EverandWhite Jacket Required: A Culinary Coming-of-Age StoryRating: 2 out of 5 stars2/5 (9)

- The Settler's Cookbook: A Memoir of Love, Migration and FoodFrom EverandThe Settler's Cookbook: A Memoir of Love, Migration and FoodRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (4)

- Organic Tales From Indian Kitchens: WARM SPICE AND EVERYTHING NICE__HEART-WARMING STORIES AND RECIPES FROM KITCHEN TABLES IN TWO CONTINENTSFrom EverandOrganic Tales From Indian Kitchens: WARM SPICE AND EVERYTHING NICE__HEART-WARMING STORIES AND RECIPES FROM KITCHEN TABLES IN TWO CONTINENTSNo ratings yet

- A Neighborhood Café: A Guide and Celebration of Healthy Food and Community Engagement, Color EditionFrom EverandA Neighborhood Café: A Guide and Celebration of Healthy Food and Community Engagement, Color EditionNo ratings yet

- Profiles from the Kitchen: What Great Cooks Have Taught Us about Ourselves and Our FoodFrom EverandProfiles from the Kitchen: What Great Cooks Have Taught Us about Ourselves and Our FoodRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- Wild Women in the Kitchen: 101 Rambunctious Recipes & 99 Tasty TalesFrom EverandWild Women in the Kitchen: 101 Rambunctious Recipes & 99 Tasty TalesNo ratings yet

- Difficulty LevelDocument6 pagesDifficulty LevelElena-Adriana MitranNo ratings yet

- Spanish 837- Food Autobiography TemplateDocument5 pagesSpanish 837- Food Autobiography TemplateVlad Vexillogist CarreroNo ratings yet

- My Big Fat Greek Cookbook: Classic Mediterranean Soul Food RecipesFrom EverandMy Big Fat Greek Cookbook: Classic Mediterranean Soul Food RecipesRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- A Mouthful of Stars: A Constellation of Favorite Recipes from My World TravelsFrom EverandA Mouthful of Stars: A Constellation of Favorite Recipes from My World TravelsRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5)

- Going with the Grain: A Wandering Bread Lover Takes a Bite Out of LifeFrom EverandGoing with the Grain: A Wandering Bread Lover Takes a Bite Out of LifeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (3)

- Damn Good Chinese Food: Dumplings, Egg Rolls, Bao Buns, Sesame Noodles, Roast Duck, Fried Rice, and More—50 Recipes Inspired by Life in ChinatownFrom EverandDamn Good Chinese Food: Dumplings, Egg Rolls, Bao Buns, Sesame Noodles, Roast Duck, Fried Rice, and More—50 Recipes Inspired by Life in ChinatownNo ratings yet

- Try This: Traveling the Globe Without Leaving the TableFrom EverandTry This: Traveling the Globe Without Leaving the TableRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (12)

- Pasta, Pretty Please: A Vibrant Approach to Handmade NoodlesFrom EverandPasta, Pretty Please: A Vibrant Approach to Handmade NoodlesNo ratings yet

- Seasons in the Wine Country: Recipes from the Culinary Institute of America at GreystoneFrom EverandSeasons in the Wine Country: Recipes from the Culinary Institute of America at GreystoneRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- Punk Philosopher's World of Underwear, Nukes, and RockDocument5 pagesPunk Philosopher's World of Underwear, Nukes, and RockYASMEEN HALUMNo ratings yet

- Flavors from Home: Refugees in Kentucky Share Their Stories and Comfort FoodsFrom EverandFlavors from Home: Refugees in Kentucky Share Their Stories and Comfort FoodsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

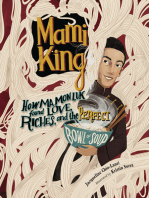

- Mami King: How Ma Mon Luk Found Love, Riches, and the Perfect Bowl of SoupFrom EverandMami King: How Ma Mon Luk Found Love, Riches, and the Perfect Bowl of SoupNo ratings yet

- Savory Bites: Meals You Can Make in Your Cupcake PanFrom EverandSavory Bites: Meals You Can Make in Your Cupcake PanRating: 2.5 out of 5 stars2.5/5 (3)

- Excerpt Jabu Goes To Joburg, The Fotonovela Featured in The Latest Edition of Chimurenga's CronicDocument6 pagesExcerpt Jabu Goes To Joburg, The Fotonovela Featured in The Latest Edition of Chimurenga's CronicSA BooksNo ratings yet

- 2016 Abantu Book Festival ProgrammeDocument16 pages2016 Abantu Book Festival ProgrammeSA Books100% (1)

- 2016 Kimberley Book FairDocument3 pages2016 Kimberley Book FairSA BooksNo ratings yet

- Double Echo by François BloemhofDocument6 pagesDouble Echo by François BloemhofSA BooksNo ratings yet

- An Excerpt From Green in Black-and-White Times: Conversations With Douglas LivingstoneDocument27 pagesAn Excerpt From Green in Black-and-White Times: Conversations With Douglas LivingstoneSA BooksNo ratings yet

- 2016 Time of The Writer ProgrammeDocument3 pages2016 Time of The Writer ProgrammeSA BooksNo ratings yet

- Bleek's Scholarly Life Far From Bleak - Weekend Argus April 30, 2016Document1 pageBleek's Scholarly Life Far From Bleak - Weekend Argus April 30, 2016SA BooksNo ratings yet

- Introductin To Protest Nation: The Right To Protest in South AfricaDocument23 pagesIntroductin To Protest Nation: The Right To Protest in South AfricaSA BooksNo ratings yet

- 2016 Open Book ProgrammeDocument7 pages2016 Open Book ProgrammeSA BooksNo ratings yet

- Prologue Jan Smuts: Unafraid of GreatnessDocument16 pagesPrologue Jan Smuts: Unafraid of GreatnessSA Books0% (1)

- Flame Extract 3 November 1963Document5 pagesFlame Extract 3 November 1963SA BooksNo ratings yet

- Flame Extract 2 August 1963Document3 pagesFlame Extract 2 August 1963SA BooksNo ratings yet

- Flame in The Snow Extract 1 MayApril1963Document7 pagesFlame in The Snow Extract 1 MayApril1963SA BooksNo ratings yet

- 2016 Puku Story Festival Isixhosa ProgrammeDocument6 pages2016 Puku Story Festival Isixhosa ProgrammeSA Books0% (1)

- 2015 Time of The Writer Festival ProgrammeDocument2 pages2015 Time of The Writer Festival ProgrammeSA BooksNo ratings yet

- 2016 Puku Story Festival English ProgrammeDocument6 pages2016 Puku Story Festival English ProgrammeSA BooksNo ratings yet

- Power Politics in Zimbabwe - ExcerptDocument15 pagesPower Politics in Zimbabwe - ExcerptSA BooksNo ratings yet

- 8 Jan 1995Document1 page8 Jan 1995SA BooksNo ratings yet

- French Reviews of Imperfect SoloDocument12 pagesFrench Reviews of Imperfect SoloSA BooksNo ratings yet

- Remembering Joe SlovoDocument1 pageRemembering Joe SlovoSA BooksNo ratings yet

- Excerpt From Back To Angola by Paul MorrisDocument14 pagesExcerpt From Back To Angola by Paul MorrisSA BooksNo ratings yet

- David Bowie's Space Oddity, The Children's BookDocument21 pagesDavid Bowie's Space Oddity, The Children's BookSA BooksNo ratings yet

- 8 Jan 1995Document1 page8 Jan 1995SA BooksNo ratings yet

- Remembering Joe SlovoDocument1 pageRemembering Joe SlovoSA BooksNo ratings yet

- 8 Jan 1995Document1 page8 Jan 1995SA BooksNo ratings yet

- Herman Mashaba Offers Himself As Mayoral Candidate For The DA For Johannesburg 2016Document1 pageHerman Mashaba Offers Himself As Mayoral Candidate For The DA For Johannesburg 2016SA BooksNo ratings yet

- Remembering Joe SlovoDocument1 pageRemembering Joe SlovoSA BooksNo ratings yet

- Dangerous Snakes of Southern AfricaDocument1 pageDangerous Snakes of Southern AfricaSA BooksNo ratings yet

- Cafe Isis MenuDocument8 pagesCafe Isis Menufm7236No ratings yet

- Alkaline Food ChartDocument2 pagesAlkaline Food ChartRamakrishna Kondapalli100% (1)

- Restaurant Questionnaire FormDocument1 pageRestaurant Questionnaire FormMarco TanilonNo ratings yet

- Prem GanapathyDocument7 pagesPrem GanapathyAshwini PrabhakaranNo ratings yet

- Jesse MenuDocument5 pagesJesse Menusupport_local_flavorNo ratings yet

- Catalog Orlandos - Web PDFDocument18 pagesCatalog Orlandos - Web PDFGeorge PreoteasaNo ratings yet

- Turkish RecipesDocument27 pagesTurkish Recipesluminita_elena_7100% (1)

- Company Name Order Date Product AmountDocument52 pagesCompany Name Order Date Product AmountDaniel KaminskiNo ratings yet

- Bakso - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaDocument3 pagesBakso - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaTyas Te PyNo ratings yet

- Mardi Gras Recipe Sampler by Mitchell Rosenthal, Author of Cooking My Way Back HomeDocument13 pagesMardi Gras Recipe Sampler by Mitchell Rosenthal, Author of Cooking My Way Back HomeThe Recipe Club100% (1)

- Americas 20 Worst Restaurant MealsDocument20 pagesAmericas 20 Worst Restaurant MealsBrianW100% (5)

- GRADE 9 NOTES (1) - PREPARING SANDWICHES #CookeryDocument9 pagesGRADE 9 NOTES (1) - PREPARING SANDWICHES #CookeryRain JannelaNo ratings yet

- 1 NovDocument2,565 pages1 NovemperorahmadkhokharNo ratings yet

- ScriptDocument8 pagesScriptromaniskieeNo ratings yet

- Fish and ShellfishDocument45 pagesFish and ShellfishShommer ShotsNo ratings yet

- The Bread Baker BibleDocument357 pagesThe Bread Baker Biblemrsyedibrahim6642No ratings yet

- Menu Engineering Chapter 1Document47 pagesMenu Engineering Chapter 1Rizkiy A. Fadlillah100% (2)

- Tender Staff CollegeDocument13 pagesTender Staff Collegecvmp2No ratings yet

- Apple Chocolate Smoothie - Sharmis PassionsDocument4 pagesApple Chocolate Smoothie - Sharmis PassionsAircc AirccseNo ratings yet

- List of Books For Teachers ReferencesDocument5 pagesList of Books For Teachers ReferencesClenchtone CelizNo ratings yet

- Explore Edinburgh's Past and PresentDocument12 pagesExplore Edinburgh's Past and PresentNick JansenNo ratings yet

- Coosh's Bayou Rouge MenuDocument6 pagesCoosh's Bayou Rouge MenuchakamadNo ratings yet

- Master Recipe-Book-Commissary Fig and OliveDocument4 pagesMaster Recipe-Book-Commissary Fig and Oliveapi-285577823No ratings yet

- Countable and Uncountable Nouns ExercisesDocument4 pagesCountable and Uncountable Nouns ExercisesJuan Carlos JCNo ratings yet

- List of Dinning Employee For Regular: Name Allowance Total Salary SalaryDocument3 pagesList of Dinning Employee For Regular: Name Allowance Total Salary SalaryMESA SM TANZANo ratings yet

- Leading Source Magazine Summer 2007Document44 pagesLeading Source Magazine Summer 2007castellar89No ratings yet

- Cookery VS CulinaryDocument4 pagesCookery VS CulinaryJuli Hyla RomanoNo ratings yet

- Stocks: Ingredients in Preparing StocksDocument5 pagesStocks: Ingredients in Preparing StocksKelzie Nicole Elizar100% (1)

- Bake From Scratch - Winter - 2016Document117 pagesBake From Scratch - Winter - 2016pazz0100% (8)

- Intermediate Unit 9bDocument2 pagesIntermediate Unit 9bgallipatero100% (1)