Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Judith Deutsch Kornblatt - Solov'Ev's Androgynous Sophia and The Jewish Kabbalah

Uploaded by

kingkrome9990 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

31 views10 pagesliterature, rusia

Original Title

Judith Deutsch Kornblatt - Solov'Ev's Androgynous Sophia and the Jewish Kabbalah

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this Documentliterature, rusia

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

31 views10 pagesJudith Deutsch Kornblatt - Solov'Ev's Androgynous Sophia and The Jewish Kabbalah

Uploaded by

kingkrome999literature, rusia

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 10

ARTICLES

JUDITH DEUTSCH KORNBLATT

Solov'ev’s Androgynous Sophia and the Jewish Kabbalah.

‘The revival of Russian Orthodoxy at the tum of the century coincided with a wave of anti-

Scmitism, and many Russian intellectuals of the time, following Viadimir Solov‘ev, understood

the defense of the Jews as their Christian duty. For Solov'ev, however, interest in the Jews went

beyond ethical considerations and ran deeper through his philosophy than even his utopian vision

of a theocracy based on Hebrew Seriptures. Indeed, the expression of what may be Solov’ev's

central concept-—the Divine Sophia—achieved clarity through his setective reading of the Jew=

ish mystical tradition of Kabbalah. The argument that follows docs not seek to prove influence,

for Solov'ev approached the study of Kabbalah with well-formed philosophical convictions.

Rather, Solav’ev’s fascination with Jewish mysticism arises from affinity and recognition, as the

Russian theologian sought a vocabulary with which to explain his own mystical intuitions.

Distegarding major discrepancies between Jewish mysticism and Christian Trinitarian

dogma, Solov’ev found in Kabbalah confirmation of his mystical vision of an erotic yet an-

drogynous ideal within the Godhead. He understood Kabbalah’s multiple hypostases of the one

living God, who act like humans and are acted upon by mortal men and women, as expressions

Of his own connection to the divine world Uuough Sophia. It is this vision of Sophia that origi-

nally appeared in La Russie et léglise universelle when it was first published in France in 1889.'

‘The French version complements an earlier version of Solov'ev's sophiology found in Chteniia o

bogochelovechestee (E8T?-- 1881).

{in the Chteniia, Solov’ev speaks largely in the Schellingian-Hegetian language popular dur-

ing his university years and tries to explain cosmogony, anthropology, and the history of 1

through a logical tripartite system, He aims at alt times to identify a third principle that recon

ciles the apparent dualism of spicit and matter, transcendent truth and sensual experience. In

Sophia, Solov'ev finds & parmer for the abstract Logos, and she becomes the connecting prin-

ciple between Ged and humanity. She is the paradoxical “body of God, divine matter” (3: LIS),

both subject and object at once (3:140). As Solov’ev asserts that humanity is the fink between

the divine and natural worlds, ke calls Sophia ideat'nyi chelovek (3:121}. The body of Gud, she

is also the soul of the world, the incarnated divine idea (3: 127, 146). Despite (his reference to

incarnation, the Sophia of Chtenita remains an abstract idea! approachable through rational con-

templation. leven the World Soul, which causes evil to enter the prenatural wortd (3: 535, 142),

appeats as a rational phenomenon and, thus, is seemingly unrelated to Solov’ev's mystical vision

of the Divine Female.

‘The Sophia of La Russie ei I’ église universetle seeks her justification within biblical revela~

tion instead of German idealism. On the surface she is also more identifiably femaie, being

called variously wife, mother, girlfriend, and fiancée. uniting with man and giving birth. ‘The

issue of her gender, however, is a complicated one, The Greeks identified Sophia with Logos.

‘A Shorter version of this article was fist presented atthe annual meeting ofthe American Association forthe

Advancement of Slavic Studies, Chicago, 1989,

1. La Russie et Pégtive universette (Paris: Librairie Nowvelle Parisienne, 1889), Translated in 1911 by

G. A. Rachinski, this work svas included in Sobrante Sochinenii Vladimira Sergeevicha Solor' eva, 12 vols

(Brussels: Zhizn’ s Bogom, 1969) 11:139-348, Unless otherwise stated, all quotations from Solav'ey will

be fiom this edition and will be indicated in the text in parenthesis,

Siavic Kevfew 50, no. 3 (Fall 1990)

488, Slavic Review

Solov’ev tells us, but Russians (who have a particular bent toward mysticism, 3: 181) tied her to

both the Mother af God and to Jesus Christ, and ultimately understood her as a separate individ-

ual image of the Divine, a social incarnation of the Divine in the universal church (11:310, 309).

Truly, we have here that same substantial form [designated by the Bible as the seed of

woman, i.e,, Sophia], revealing herself in three successive and abiding manifestation

reality separate, but in essence indivisible, assuming the name of Mary in its female person-

ification, of Jesus in its male personification —and preserving its own name for is fall and

universal manifestation in the perfect Church of the future, in the fiancée and wife of the

Word of God.

‘This Sophia, identified as both male and female, both individual and communal, recatls a Chris~

tianized, and sexually ambiguous, member of the Kabbalistic family.

Solov'ev's knowledge of Kabbalah is easily documented. in 1896 he wrote a scholarly in-

troduction to “Kabbalah: Mystical Philosophy of the Jews” by David Gintsburg and, later, draw-

on Gintsburg 4s well as German and French sources, contributed the entry on Kabbalh to

the Brokgaus-Efron Encyclopedia,’ By this time Sotov‘ev hud learned the language well enough

to read Hebrew Scripture in the original and had committed himself to the study of Talmud and

Jewish medieval philosophy. Solov’ev’s interest in Jewish mysticism had no doubt begun much

earlier, while he studied independently at the Moscow Spiritual Academy during the mid-1870s.

S.M. Luk‘ianov cites a report, submitted in 1875 in the name of the young scholar, that re-

quested permission for temporaty leave from the post of docent of philosophy at Moscow Uni-

Solov'ey intended to travel to London for research in the British Museum on “Indian,

‘gnostic, and medieval phitosophy."** Whether this “medieval philosophy” actually meant Kab-

alah at first is stil! unclear,” but that it became Kabbalah is attested to by the memoirs of LL

Janzhut with whom Solov‘ev socialized in London. lanzhut claims to have seen Solov’ev poring

over the bizarre illustrations from 4 hook on Kabbalah and to have heard him declare: “It is very

interesting; in every line of this book there is more life than in alt of European scholarship.

Lam very happy and content to have found this edition.”*

White at the British Museum, Solov’ev alleged that he had his second direct experience of

the Divine Sophia (the first having occurred in childhood) and decided to travel to Egypt to seck

a third mecting. Although an acquaintance who saw the young mystic in Egypt weites that Solo-

v'ev nianaged to do no more in the desert than lose his wateh to Bedouins," the poet insisted he

fulfilled his mission, seeing his thitd and fullest vision of the Sophia: “Today, wrapped in

azure,/My tsaritsa has appeared before me.""'

‘A notebook used by Solov'ev during his stay in London contains a short prayer to Sophia

2. David Ginsburg, “Kubbsia, misticheskaia flosofiia evreev,"” Voprosy filosoft i psikhotogit 33

£1896: 279-300. The introduction aione is reprinted inthe Brussels edition of Sotov‘ev (12:332- 334), The

encyclopedia article is found in 10:339-343.

3. S.M. Luk’ianov, © Viadintire Soloy'eve v ego molodve gody: materialy k biografit, 3 vols, (Pet-

rogtad: Gosudarsivennaia, 1916-1921) 3:64, Drawing heavily on Luk’ianov, Sergei Sotoy’ev describes his

uncle’ Stay abroad in S.M. Solov'ev. Zhien’ norchestuia evoliutsiia Vladimira Solov'eva (Brussels:

Zhizn’ s Bogom, 1977), 114-152.

4, Hebrew was taught in the seminary, and the seminary library contained books on Jewish as well as

other medieval raysticisms. Furthermore. Solov’ev probably hat! read Eliphas Lévi, a major source on e

tericism in general. including references to Kabbalah. Interest in and translation of Jewish texts was high

during the reign of Alexander If (see Nikolai Rizhskii, stortia perevoda Biblii v Rossii (Novostbirsk: Navka,

1978}, 155-170, esp. 158-164) and mystical societies proliferated

3. LL. fanzhul, “Vospominaniia 11, Ianzhuls 9 perezhitom i vidennom.” Russkaia starina 14

(9D): 481-482,

6, BM, de Vogié. “Un docteur russe Viadimir Solovief.” Sous Pherizon: Hommes et choses d'hier,

2nd ed. (Paris, 1903}. 15-25; this srtile is reproduced in A. Nikiforaki, “Inostranets o russkom.” Russkoe

Obozrenie | (1901): 117-123 and also cited in Luk"ianov. “ Vospominaniia.” 260,

7. Vladimir Soiov'ev, Stikhotvoreniia i shutochne p’esy, Biblioteka pocta serien (Leningrad: Sovet-

skii pisate!’, 1974), 61, See also the description of his visions of Sophia in “Tei wwidaniia,” ibid, 125~132,

Solov'ev's Androgynous Sophia and the Jewish Kabbalah 489

that some scholars have called the translation of a Gnostic incantation." Although much of the

imagery in this prayer is decidedly Gnostic (including typical allusions to roses and fifies}, the

second line, pointing to Kabbalistic influences, uses vocabulary that postdates Gnosticism and

suggests that Solov’ev himself wrote the incantation.

‘The entry begins “In the name of the Father and Son and Holy Spirit”; and it continues,

using Latia letters "An-Soph, Jah, Soph-Jah."* “An-Soph” clearly refers to the transcendent,

unknowabie Godhead of Kabbalah: Ein-Sof, which is mentioned by Solov‘ev in his 1876 French

article “Sophie,” and teansliterated into Russian as “én-sof” in “Filosofskie nachala tsel’nogo

znaniia” (1877). Jah is one of the many biblical names of the one God, the discussion, atrange-

ment, and interpretation of which form the core of speculative Kabbalah." The name is usually

associated with the sefirah, or divine manifestation of, Hokhmah (wisdom). Solov'ev thea, in a

technique reminiscent of the wordplay of Kabbalah, derives “Sophia” from the union of Soph,

meaning end in Hebrew, and Jah. “Soph-Jah™ corresponds to the Holy Spirit in the first line of

the prayer’s invocation, and Solov’ev thus makes “the end of God” into the third divine hypo-

stasis. In all of Solov’ev, the third principle is a bridge or connector, and in this case the inter-

mediary unites God and man. as the subsequent prayer makes clear: “Descend into the dungeon

of the soul,” he pleads, and “fill our darkness with your radiance” (12: 149). Soph-Jah thus

moves God from transcendence to immanence, so that the end of God is man, This early manu-

seript demonstrates Solov’ev’s understanding of Kabbalistic vocabulary, method, and, most im-

portant, theology, for the sefirat, beginning with Hokhmah, are the connecting links between sn

eternal Godhead and humanity,

Solov'ew traces the name Sophia-—-wisdom, or Premudrost’ in Russian—~back through

Gnosticism and Kabbalah to the Old Testament in Proverbs 8-9 ("Wisdom huth builded her

house, she hath hewn out her seven piltars,” Prov. 9: 1), as well as to the apocryphal Jewish text,

the Wisdom of Solomon ("I came to know everything, both the hidden and the revealed. for I

‘was taught by Wisdom, the artist of all,” Wis. of Sol, 7:21) (2: 115: 11-288).

8, The prayer was discovered by S, M. Solov‘ev and first published by him in “Ideia tserkvi v poezii

Viadimira Soiov'eva,” Bugastovskit vesontk (January 1915), 74, Sergei Buigakov reprinted it in * Vladimir

Solov'ev i Anna Shmidt.” Tikhie Dumy (Moscow: Leman i Sakharov, 1918), 74, and argues, I believe incor

rectly, thatthe prayer was copied from a Gnostic text, perhaps found by Solov'ev in the British Museum. The

text may be found in the Brussels edition (12: 148-149)

9. "This second tine was not printed in 8, M, Solov‘ev's first publication of the prayer but was added in

the sixth edition of Solov‘ev’s poetry. See commentary by Luk'ianay, “"Vospominaniia,” 146,

10. La Sophia et fes autre éerits francais, e8. Frangois Rouleau (Lausanne: La Cit-L Age d’Homine,

1978), 18, 79 (the article “Sophie” is not ineiuted in the Brusseis edition) ‘The reference to Kabbalah in this

invocation has been recognized by Luk'ianov, “'Vospominaniie,” 146, and by subsequent scholars, includ-

ing Dmitrii Stremooukhoft, but has never been fully analyzed. For references to Sotov'ev’s use of Kabbalah,

see Dmitrit Stremmooukhoff, Vladimir Soloview and His Messianic Work, \rans. Elizabeth Mevendorff, ed,

Phillip Guilbeau and Heather Elise MacGregor (Belmont, Muss.: Norland, 19803, 50-51, 83, 20t--204,

306-307. 343n, 365n; A. F. Lose, Vt. Solor’ev (Moscow: Mysl’, 1983), 62-77, and Eich Klum, Natur,

Kunst und Liebe in der Philosophie Vladimir Solo evs: Eine retigionsphitosophische Untersuchung (Mutich:

Sagner, 1965), 20, 32, 255-257.

LL. Gershorn G, Schotem is the foremost scholar of Kabbalah: See Major Trends in Jewish Mysticism

(New York: Schocken, 1954); Jewish Grasticism, Merkaba Mysticism, and Talmudéc Tradition (New York:

Jewish Theological Seminary of America, 1960); On Kabbalah and tts Symbolism (New York: Schocken.

1965y, and Kabbalah {New York: Dorset, 1974), among others. Moshe Idel, who has specifically studied

‘gender and eroticism in Kabbalah, recently chalienged some of Scholem’s assumptions in Kabbalah: New

Perspectives (New Haven, Comin: Yale University Press, 1988). For a very readable introduction to Kab-

batsh, see Lawrence Fine, “Kabbalistic Texts," im Back to the Sources: Reading the Classic Jewish Texts,

ed. Barry W. Holtz (New York: Summit, 1984}. | would jike to express my thanks to Daniel Matt for his

assistance in the study of Kabbalah,

12. This house with seven pillars ftom Proverbs opens Solov‘ev's Sophianic poem that begins: “U

tsaritsy moei est’ yysekii dvorets,/ O semi on stolbakh zolotykh” (Stikhotvorentia, 62). Solov'ev wrote the

poem during his stay in Egypt. Other speculations on Wisdom appear in Job 28:12~28, ancl a sezies of

apocryphal books, inctading the Siavonic book of Enoch. See Gershom Scholem, “Schechina; das passiv=

490 Slavic Review

"The Greek Sophia, Solov’ev tells us, is Hokhmah in Hebrew and is personified as female in

the biblical texts (11 288-289), Despite Solov'ev's association of his Divine Sophia with the

Wisdorn of these early texts, Hokhmah remains there a ereation of God, albeit the primal one.

She becomes a divine hypostasis only in tater mysticism.

Jewish mysticism developed the doctrine of Ein-Sof, the “Endless,” unknowable Godhead,

and of the ten sefirot, or manifestations of God, that emanate from it, of which Hokhmah is one.

‘That Solov’ev's Wisdom participates in the Kabbalistic sefirof as much or even more than in the

biblical and Gnostic traditions is obvious from the connection he draws not only between Sophia

and Hokhmah (usually male in Kabbalah), but between Sophia and Shekhinah or Malkhut (Fe-

male), the tenth sefirah.” Deciphering the gender confusion between Hokhmah and Shekhinat

in Solov’ev’s allusions to Sophia in La Russie et Péelise universelie may help explain Divine

Wisdom and its relationship to the World Soul and also give insight into his remarks on gender

sand androgyny, for which he may have found support in the eroticism of medieval Kabbalistic

theosophy.

‘The Zohar is perhaps the best-known Kabbalistic text, and the one that Solov'ev may have

studied in Latin during his stay in London. "* Largely an exegesis on the first five books of the

Hebrew Scripture, Zohar is reputed to have been written in the second century by Rav Shim’on

ben Yohai but is actually an elaborate thirteenth century forgery by the Spanish Kabbalist, Moses

b, Shem Tov de Léon. After a lengthy prologue, the Zohar opens with an interpretation of Gene-

sis, frequently verse by verse. The first selection describes the birth of the sefiror in a manner

similar to most Kubbalistic teaching: Bin-Sof or Keter, the first sefirah and here considered co-

eternal with Bin-Sof, allows for the existence of Hokhmah."” Hokhmah is father and is paired

with the next sefiral, Binah, who is mother. ‘The two then unite to give birth to the following

seven sefirot. Together, the sefirot are sometimes diagrammed as representing various limbs of

the tiuman body, with the suggestion that the right-hand members are masculine and the left,

feminine. The lower sefirot also form a sexual union; Tiferet (male) unites through Yesud (repre-

sented as the male sexual organ) with Shekhinah (female), which is the closest sefirah (0 human-

ity and is the first to have direct dealings with mortals.

‘Therefore, in Kabbalah it is not Hokhmah but Shekhivah who becomes the female partner

to the masculine mystic and to all men.“ Her main appellative in the Zohar is, in fact. Female.

She is the closest stage to the human world, and entrance into the divine realm must be made

trough her “gates,” ar erotic metaphor.” Kabbalah describes sexual relations between the

‘weibliche Moment in det Gottheit.” Vor der ngstischen Gestalt der Gottheit: Studien zu Grandoegrifen der

Kabbala (Frankfurt a.R.: Suhrkamp, 1977), 135-140; and Raphael Patsi, The Hebrew Goddess (New York

KTAV, 1967), 139,

13. The sefiror in descending order are Keter (crown), Hokhinah «wisdom, Bina (understanding),

Gedulab or Hesed (kindness), Gevurah of Din (harsh jadgment), Tiferet (beauty), Netsah (iumph), Hod

{glory}, Yesod (foundation), and Malkhat or Shekhinah (Kindyom or indwelling of God).

14, Stremooukhoff, Soloviev and His Messianic Work, 343, convincingly speculates that the book in

question is Christian Knorr von Rosenroth, Kabbala denudata + (Sulzbach: Lichtenthaler, 1677) and 2

(Frankfurt: Zunneri, 1684),

15. Later Lurianie Kabbalah refers to this process as a contraction into Itself, Although the Zohar

rarely uses the names of the sefirat, the terms it chooses for the ten manifestations of God correspond to the

traditional ones. and medieval commentators on the Zohar inserted them with no difficulty. Por a table of

correspondence, see The Zohar, tans. Hatry Sperling and Maurice Simon, S vols. (London: Soncino, 1984)

12385,

16, A similarity might be noted between Solov'ev and Kabbalah. for neither postulate a femate mystic.

‘Scholem writes, “one final observation should he made on the general character of Kabbalism as distinet

from other, non-Jewish, forms of mysticism. Both historically and metaphysicaly it is a masculine doctrine,

made for men and by men,” Scholem, Major Trends, 37.

17. ~The emphasis placed om the female principle in the symbolism of the last Sefirah heightens the

mythical language of these descriptions. Appearing from above as “the end of thought.” the last Sefirah is for

Solov'ev's Androgynous Sophia and the Jewish Kabbalah 49)

sefiror modcled on snale-Female intercourse on carth (as below, so above) and reinforces a tradi-

tional Jewish concern for inaritat refatious. As opposed to the treatment of sex in other mystical

systems in Kabbalah sex gives life not death, and one way of uniting with Shekhinah is for a

Jewish man to have sextal intercourse with his wife on the Sabbath."

For both Kabbalah and Solov'ev, the intimate connection between God and man is more

than metaphor. According to Kabbalistic texts, human actions affect the balance of power within

the divine world.” Proper fulfillment of the faws of the Torah increases the flow of divine light

from the Godhead, called the shefa, and the makeup of the divine structure is therefore governed

by human beings. For Solov'ev, social action, that is, man's engagement Here on earth, inti-

mately affects the Kingdom of God, He condemns philosophers who withdraw from te sociat

arena (11:240, 318), criticizes his own church for ils wortdly apathy (11175), and praises the

Jows precisely for their orientation toward the human world and their activism that brings them

closer to the Kingdom of Heaven. °

Kabbalah perhaps attracted Solov'ev because of its understanding of these very tangible

relations between God and humanity. Although Solov’ev studied eastern philosophy as avidly as

he did Jewish theology. ite ultimately rejected Buddhism for its idealization of nothingness. as

opposed to human reality (3:45, 48; 11:320). Gnosticism, despite its influence an him, draws

Sotov’ev’s wrath for its teaching, as he says, that the world cannot be saved (10:325), Despite

his borrowed ideas from Platonic ideatism, Solov'ev also turned from it because of its dualisin

and ultimate rejection of the world of man (11322). Both Buddhism and Platonic philosophy,

Solov'ev claims, are only stages on the path toward true revelation, The carly seventeenth cen-

tury mystic Jacob Bochme, whose theasophy strongly recalls Kabbalah, is perhaps closest to

Solov'ev's mystical orientation, although Bochme lacked the erudition that undeslies Solov'ev's

vision of Godmanhood.””

Neither Kabbalah nor Solov‘ew preach sexual asceticism, although Solov‘ev seems to

understand sexual relations more abstractly than does Jewish mysticism.” In order to preserve

trata the door oF gate through which fe can begin the ascent up the ladder of perception of the Divine Mys-

tery.” Scholem, Kabbalah, 112,

18, Moshe Tel, “Métaphores et pratiques sexuettes das ta Cabale.” ia Lettre sur la Sainteté Le

Secret de ta relation entre i'hamme ct ta femme dans ta Cabate. trans. Charles Mopsik (Paris: Verdier,

1986), 336-338, 344, 347.

19. “Thus, aman is conceived of as am active factor able to snteract with the dynam

balistc anthropokogy and theosophy, then, ase both similar and complementary perceptions,

spectives, 166.

20, See Joseph Dan, Gershum Scholem and the Mystical Dimension of Jewish History (New York.

New York University, 1987), 221. Solov'ev elaims: “The Jews] alone understood tne redemption... 40

the sanctification and renaissance of the entire human essence and aft ofits being. by the say of living moral

and religious activism, in faith and deeds, in prayer, is work und charity” (11322).

21. For an analysis of Solov'ev’s attitude toward eastern mysticism, see Jonattian Sutton, The Rel

‘gious Philosophy of Vladimir Salovyov: Towards a Reassessment (New York. St. Martin’s Press, 1988),

161 178. Samuel D, Cioran argues for the influence of Gnosticism in Vladimir Solov'ev aad the Knighthood

of the Divine Sophia (Waterloo, Ont. Wilfrid Lausier University Press, MF7!), 12~21. The late Donstd C.

Gillis began a project on “Gnosis and Cabate in the Barly Works of Vladimir Solov‘ev,” and Tum thankful

for the use of his short unpublished manuscript. Valentinian Gnosticism includes an “upper” and “Hower”

Sophia that probably influenced Solov'ev’s own soinetimes dust Sophia, but uniike Solov'ev's, the Valenti-

‘sian Sophia always remained a troublemaker in the created world. See Haas Jonas, The Gnostic Religion:

The Message of the Alien God and the Beginnings of Christianity, 2nd ed. (Boston: Beacon, 1962),

176.199. On Bochme and Kabbalah, see Scholem, Major Trends, 237-238.

22, Solov’ev never married but might have agreed with the Kabhalist: “Phe mystery of sex - .. has a

terribly deep significance. This mystery of human existence is 4o¢ hiny nothing, but a symbol of the dove

between the divine ‘I’ and the divine “You,' the Huly one, blessed be He and His Shekhinalt, .. ln God

there is a union of the aeiive and the passive, procreation and conception, from which all mundane fife and.

bliss are derived” (Scholem, Major Trends, 2271

Divinity. Kab.

del, New Per:

492 Slavic Review

the positive roles of humanity and physical matter in general within the divine drama, Solov'ev

places the Fall in the cosmogonic process, releasing people from personal guilt in original sin

(see 13:31 1 ff), Kabbalah also portrays the Falt in this way. Redemption then becomes a question

‘of mending the relations between the parties involved in the divine-human process, with man as

the potential unifier of a divided cosmos (11:312). Rather than the last stage in inherently flawed

creation. humans become the first stage in redemption.

As Solov'ev argues, the union of flesh and spirit takes place along the lines of sexual inter-

course: Wisdom finds man and rejoices in the union (11306); earth and heaven unite to create

tan (11306); the Soul and the Word unite in gladness (11 :307).*" The feminine gender in Solo-

vev, therefore, does not unambiguously represent evil or cormuption of the flesh, as it does in

Gnosticism and in the philosophy of the Jewish Hellenist, Philo, for example, about whom Solo-

v'ev also writes. When not intentionally confusing her gender. as we will see below, Solov'ev

insists on the femininity of his divine Sophia and clevates erotic love to the role of divine medi-

ator.” For him, the goa! of humanity is not "to make the female male"—where “female” sig-

nifies sinful Hesh and “male” pore spirit—but itis rather the true and (e)productive unification

of mate and female. Jo Fact sexual love leads humanity along “the path toward the image and

likeness of God, to the union of male and female principtes io androgyny. the ‘whale human

being’,” (9:234), Solov’ev may have found confirmation for this intuition in the Zohar, which

explains: “Any image that does not embrace male and female is not a high and true image,” and

a human being is only called Adam when male and female are as one” (Zohar 1:55b).”* For

both Kabbatah and Solov’ev, the ideat is bisexual not asexual.

The real differences between Kabbalah and Solov‘ev cannot be disregarded, but they may

explain Solov‘ev's misreading of Kabbalistic theogony. While Kabbutists understood their writ-

ings as interpretations of an existing tradition, Solov‘ev saw his philosophy as the foundation of

a new ecumenical church, He betieved he could choose only those aspects of existing traditions

that supported his vision and could combine them into a true religious and social order. Because

that synthetic order is based on the concept of unity, Solov'ev tended to equate diverse elements

of the systems that he studied, disregarding their unique functions within individual traditions.

“Thus, Solov‘ev adopted Kabbalah’s eroticization of the sefiror to his explanation of the relation

‘of Sophia to the divine hypostases and to man but never clarified the relation between the persons

of the Trinity and Kabbalistic manifestations of Ein-Sof. He correctly understood the difference

between the sefivor and neo-Platonic emanations of the Divine, since the fatter are all to some

degree lesser than the Prime Mover, but he then assumed that he could thus equate Ein-Sof with

God the Father, since all the members of the Trinity are equally divine. This assumption seri-

ously “tinitizes" Kabbalah, as we see in a diagram Solov‘ev sketched in the margin of his essay

“Sophie.” where a tinity of Ein-Sof, Logos. and Sophia correspond to Spirit, Intellect, and

Soul.” Given his tendency to read Kabbalah as confirmation of his own synphetic ‘Trinitarian

vision, Solov’ev conflated the mate Hokhmah and female Shekhinah, as we shall see

Solov'ev identifies Shekhinah in various ways, including the “divine power and glory.

which is revealed to all peoples (11322), perhaps influenced by Kabbaiah’s epithet for her:

“Glory of God.” In the most Kabbalistic of his writings, however—part 3, chapter 5 of La

23. See also “Smysl ttubyi.”* 7:48.

24. See, for example, Solov‘ev’s introduction to the third edition of his poetry, reprinted in Stikio-

rvorenita i shucachnye p’esy (Munich: Wilhelm Fink, 1968), xii~xiii and “Tvorenie Platona’” (12:391):

“Bros is not a god, but something divine, halfway between eternal and mortal nature, 2 powerful deman who

unites heaven and garth.” See also my manuscript, “The Transfiguration of Plato in the Erotic Philosophy of

‘V1, Solov‘ev” (forthcoming). On Philo see Wayne A. Meeks, "The Image of the Androgyne: Some Uses of

44 Symbol in Earliest Christianity,” History of Religions 13 (1973}. 176, and Richard A. Buer, Jr, Phtlo’s

Use of the Categories Male and Female (Leiden: Brill, 1970), 40-44.

28. Zohar: The Book of Enlightenment, trans, Daniel Chanan Matt, preface by Arthur Green (New

York: Pautist Press, 1983), 35~56. Scolem considers the introduction of a female aspect of God, in

‘Shekhinal, “one of the most important and lasting innovations of Kabbatism” (Scholem, Major Trends, 229).

26. Set Scholem, Kabsaiah. 98, 10F. Solov’ev, “Sophie,” 79 n. 2

Soiov' ev's Androgynous Sophia and the Jewish Kabbalah 493

Russie et Péglise universelie (11;298-302)—Solov'ev refers to Shekhinah by the alternate

name for the tenth sefirah: Malkhut. Matkhut means kingship, and Shekhinah-Malkhut is, there~

fore, the manifestation of the Kingdom of Heaven, the abode of the ideal people of Israel. In

Kabbalah the last stage of divine manifestation is the first stage of human spiritualization, and

Solov'ev develops this very aspect of Malkhut in his writings on theocracy. Thus, man's union

with Shekhinah for Solov‘ev has social and political, as well as mystical ramifications.

In this “Kabbatistic” section, Solov’ev both distinguishes between Hokhmah and

Shekhinah-Matkhut and, ultimately, confuses them in his analogy with Sophia, The chapter fol-

lows several in which Solov’ev describes the relation of the divine hypostases to God in ts Ob-

Jectivity, who, like Ein-Sof in later Kabbalah, contracts into Itself in order to create an object

‘with which to interact, called God in Its Subjectivity or the Holy Trinity. From the Trinity then

proceeds God in its Relativity or Sophia, also called Hokhmah, who is multiplicity-in-unity and

is herself tripartite. In the chapter immediately preceding the one in question here, Solov’ev

further suggests that from Sophia proceeds yet another trinity that he could have called God in Its

Potentiality. or the World Soul, and from her, who cepresents space, time, and causality, comes

the world of man. (This explanation is only one of veveral regarding the relation between Sophia

and the World Soul in the following chapters.)

Solov’ev opens chapter S with bereshit (in the beginning), the first word of the Hebrew

Scripture and translates it first into Greek and Latin and then into Russian as “v nachale ili,

vernee, vo glave” (11:298). Despite a disclaimer that “it is not necessary to escape into Kab-

balistic fantasies," Solov'ev develops a decidedly Kabbalistic interpretation of this word, which

is actually a contraction of a preposition (b, meaning is: or with) and what Solov'ey believes to

be a feminine gender noun (reshit, meaning beginning).”

Solov'ev holds that it would be a misunderstanding of the spirit of ancient Hebrew to sug-

gest that “in the beginning” is a simple adverb along the lines of the Russian word snachala:

“When the Jewish people used a noun, it took that form in its direct meaning, that is, it actually

thought of a being or real object signified by that noun” (11298). Solov’ev is here, of course,

incorrect, for Hebrew, like Russian and English, includes nouns understood as concepts or used

in adverbial phrases. Solov‘ev in fact “misreads” the biblical text here through Kabbalistic eyes.

Kabbalah reads & as “with” instead of “in” end personifies reshit, and Solov’ey no doubt

learned from the Zohar its equation with Hokhmah. The Zohar reads the first half of the opening

Jine of Genesis—"'In the beginning, Elohim created” (Bereshit barah Elohim) as "Keter created

Binah by means of (with) Hokhmah.” Zohar continues (Zohar 1: 15a, Matt translation, 49-50):

With the Beginning [or Reshit-Hokhmah}

‘The Concealed One who is not known {a typical reference to Keter] created the palace [&

teference to Binah)

‘This palace is called Elohim fanother name for Binah]

The secret is:

“With Beginning, created Elohim”

Hokhmah is called reshit because itis the first sefirah or aspect of God that can be known. Binah

proceeds from Hokbmah, and the two then unite to give birth to the seven lower sefiror.

Solov‘ev makes a similarly personified interpretation of the word reshit. He, however, em-

phasizes that the noun is grammatically feminine and contrasts it fo a masculine noun from the

same root: rosh. All Hebrew words are based on three-letter roots, and playing with these roots

to form and interpret names of God is central to Kabbalistic speculation, Whence does Solov'ev

draw this specific comparison? Perhaps also from the carly pages of the Zohar. which derives

rosh, the Hebrew word for head, from an anagram of Asher, the middle term of the name of

God: Ehyeh asher ehyeh (L am that | am). Rosh is called: “the beginning which issues from

27. Reshit is actually & nour in the possessive form, and has caused biblical scholars difficulty sinee at

least the Talmudic period. Perhaps it should be translated “In the beginning of.” so that the frst fine of

Genesis would read “In the beginning of the creation of heaven and easth ... ." 4 translation that raises

serious questions about the doctrine of creation ex ninilo.

494 Slavic Review

Reshit. So when the point and the temple were firmly established together, then bereshit com:

bined the supernal Beginning with Wisdom” (Zohar 1 15a—b, Soncino translation, 64). In this

passage the Zohar is not interested in the gender of reshis or ros, and in fact has no trouble

using a feminine gender noun to designate a masculine person, the father wito plants the seed in

Binah.

For Solov'ev, however, gender is x stricter vategory. allowing his training in German phi-

losophy. Solov‘ev attempts (o evaluate faith from the point of view of reason and must adhere to

logical analysis." More significantly, he reads only that aspect of Kabbalah that will further his

definition of Sophia. Thus, he produces a reading of the biblical passage more literal than the

often literalist Zohar, The masculine noun rosh, he informs us, is used in Jewish theology to

designate God. Solov'ev may be fabricating authenticity here, as the Zohar itself does, relying

on sparious allusions to established Jewish theology, for in neither Talmudic nor mystical Juda-

ism does rosh designate God. In Kabbalah, as shown in the quotation from the Zohar cited

above, rosh is not the ultimate Godhead, which would be Ein-Sof, but an “issue” from the

“point” that is Hokhaiah, the first knowable aspect of God. or reshit, Reshit, in other words, is

the active principte in this birth, primary to rash. Despite its grammatical gender, rosh ia Kah-

balah is the passive principle.

Ina procedure again typical of Kabbalah, Solov’ev brings another biblical text to justify his

etymology. Reshit, Solov'ev continues, is the Hokbmah or Wisdom from Proverbs, who de-

clares: “"The Lord possessed me in the beginning of His way” (Adonai qanani reshit darko)

(Prov. 8:22). Thus. says Solov'ey (11:298):

Eternat Wisdom is this reshit, the feminine principle or head of all existence, as Yehova,

‘Yahwey Elohim, the Triune God, is rosh, its active principle or head, But, according to the

book of Genesis, God created heaven and earth in this beginning, in Hlis essential Wisdom.

‘This signifies that the above-mentioned Divine Wisdom represents not only the essential

and actual all-unity of the absolute essence or substance of God, but also contains within

herself the uniting power of the divided and fragmented world of being. She, the crowning

unity of everything in God, becomes both the unity of God and of extra-divine existence.

‘She represents, in this way, the true reson for creation and its goal—the principle in which,

God created heaven and earth.

So, Sophia-Hokhmah-Premudrost’ is the beginning of all creation, and also its endl; she is the

means by which Solov’ev can speak of the ultimate union of everything in God. Wisdom, he

continues, “is reshit in the beginning-the fruitful idea of unconditional unity, unified potential,

that intends to unite everything; she is Malkhut . . . in the end—the Kingdom of God, the per-

feet and fulty actualized unity of the Creator and of Creation” (11:29),

Disregarding the fact that Kabbatah’s Hokhmah is an active, masculine principle and Mal-

Khut is decidedly feminine, Solov'ev’s Sophia now has two Hebrew names:

beginning and Malkhut, or Shekhinah, in the end.

Although early Jewish Gnosticism as well as a late development of Kabbalah in Hasidism

tend to associate Hokhmah and Shekhinah, called the lower Hokhmah,” the strongest tradition in

Kabbalah associates Shekhinah rather with the third sefirak, Binah, and calts them the lower and

upper mothers. Hokhmah nonctheless dtocs have an internal connection with Shekhinah even in

classical Kabbalah, as only one among other aspects of the very rick tenth sefirah. She is as well

Mother Zion and Keneset Yistacl, for example, the latter being the glorified personification of

the ecclesia or community of Isract”’ Perhaps Solov'ey here finds the justification for his own

conflation, for he is quite explicit about the relation of bis Wisdom to the ecclesia; in the intru-

duction to Istoriia i budushchnost' teokratié (1885-1887), he calls the universat church the “is-

28. Compare Losev, Solav'er, 73.

29. ‘The system of sefirot, made even more elaborate in Lurianie Kabbalah, was collapsed in Hasid-

ism, so that Hokhmah was easily equated with Shekhinah, See Arthur Green, trans.. Menahem Nahum:

Upright Practices, The Light of the Eyes (New York: Paulist Press, 1982), 13

30, Scholem, “Schechina,”” 140-141.

Solov‘ev's Androgynous Sophia and the Jewish Kabbalah 495

tinnaia podruga Bozhiia” and “that Sophia, The Wisdom of God, to whom, in an amazing show

of prophetic sensibitity, our ancestors built altars and temples, themselves unaware of who she

is” (emphasis in original, 4:261). Sophia is the ecctesia, the ideal congregation of churches that

is God's female partner. From this description Kabbalah’s Shekhinah, not Hokhmah, might be

closer to Solov’ev’s Sophia.

‘A few chapters after the interpretation of the opening of Genesis, Solov’ev returns to the

original meaning of Shekhinah: the in-dwelling or presence of God." He writes (11.322):

fn actuality, we see in the Old ‘Testament a double row of Divine manifestations; phenom-

cena of a subjective consciousness in which God speaks (o the sout of His righteous men, to

the patriarchs and prophets; and objective phenomena in which Divine strength and glory

(Ghekina {sie}) reveal themselves before the entire people, residing on material objects such

as the sacrificial altar or the ark of the covenant.

Shekhina here is the physical manifestation of the Divine and, therefore, a manifestation of

Wisdom, for Solov'ev has just written that “Divine Wisdom not only entered into the under-

standing of the Israelites, but she possessed their hearts and souls as well, and at the same time

appeared to them ia senstal form.” This sensual form must be the Shekhinah of which he goes

on to speak, and Solov'ev implies that Shekhinah in his system is the “body” of Hokhmah.

In Chieniia 0 bogochelovechesive Solov'ev called Sophia the “body of God” (3:115), but

in La Russie et !'église universelle, Sophia herself has a body, which Solov’ev explains by re-

introducing another female actor in the cosmogonic drama: the capricious cause of evil from

Chieniia, the Wortd Soul, Here she is called the “corporeality of Wisdom" (11:310), Whece

‘Sophia had been the intermediary above, the World Soul becomes it below, Can we say then that

in Solov'ev's “reading” of Kabbalah, Sophia is Hokhmah and the World Soul is Shekhinah? Not

exactly, for while Solov‘ev's World Soul is in some sense, as her name implies, part of creation,

neither Hokhmah or Shekhinah are created beings. even though the latter has an intimate relation

with humanity, Furthermore, all the seffrot are equally significant, although tower, Shekhinah is

not fesser than Hokhmah.” If anything, Shekhingh includes Hokhmah, and not vice versa, for

the tenth sefirah incorporates all those above her.

Sophia still scems closest to Shekhinah, in whom Soiov’ev simply distinguishes an aspect

that moves toward humanity. calling her the World Suul. Like Kabbalah, Solov'ev’s system is

‘one of dialectic and process; all players can be defined only in gelation to the others. As for the

World Soul, she might turn either to chaos (our world) or to God, the latter choice resulting in

cleaving to, and identity with, Sophia (11:29). So the World Soul in La Russie et 'église uni-

verselle is potentially a synonym for Sophia but at the same time an issue from her.

How does the World Soul fulfill her potential and become Sophia’ In fact, Solov'ev identi-

fies two souls: a soul of the upper world, synonymous with Sophia, and a soul of the lower

world, synonymous with the eurth (11:305, 306), By splitting the World Sout, but retaining her

potential for unity, Solov'ev then need not differentiate Sophia from her, and Sophia need not

Jose her role as intermediary between matter and spirit. Rather, the World Sout is the means by

which Sophia bridges the two realms; she connects reshit and matkhut. The World Soul becomes

Divine Wisdom, eliminating ber own lower self, when, through her actions, the earth (feminine)

and the heavens (masculine) unite, when the lower (feminine) and upper (masculine) become one

(11306).

31. Shekkinal is formed from the Hebrew root SAKKN, meaning to dwell, as in the Mishkan, the

sanctuary in which God dwells when among men. Only in the Targum Onkelos, an Aramaic paraphrase of

the Bible, did Shekhinah begin to suggest a separate being. Where Exod. 25:8 states: “Let them make Me @

Samctuzey that f may dwelt [v'shakhansi] among them,” Targum Onkelos interpolates: “Let them make be-

fore Me a Sanctuary that I may let My Shekhinah dwell among them" (see Patai, Hebrew Goddess,

140-141),

32. This idea differs from nea-Platonism: “Although there is a specific hierarchy in the order of the

Sefirot, itis not ontologically determined: all are equally close te their source in the Emanator” (Scholem,

Kabbalah, 98, 101).

496 Slavic Review

Solov’ev has apparently wmed afound his own seemingly strict gender categories. Where

before male mankind united with female Sophia, female earth (represented by the female World

Soul) now unites with mate heaven, By bringing in the function of the World Soul, Solov’ev has

confused the issue of gender, In the analogy Solov‘ev seems to have been developing of Sophia

and Shekhinah, the divine had been female, uniting with the male mystic.

When are men “female” for Solov'ev’ This new formulation might imply that man be-

comes like the female creation when he is passive instead of active. Solovev stresses, however,

the inappropriateness of the active-passive or subject-object contrast in his system: all actors play

both roles (compare 11:307), Rather, he implies that men are “female” when they actively unite

in the chusch (always female); joined in an ideal community, they become the universal ecclesia.

Since the ecclesia is Sophia (Shekhinah in Solov’ev's Kabbalah, the “body” of Sophia), man

then becomes divine. Man does not become female, but, united with the World Soul, creates an

ideal male-female, androgynous whole (compare 9:238). In Kabbalah, man never actually be~

comes Shekhinah, despite her designation as ecclesia. Rather, the mystic enters through her into

speculation of God. Solov'ev's androgynous ideal is much more literal.

Again taking 2 cue from Kabbalah, Solov'ev sees in biblical terminology an erotic symbol

with whieh to describe the union of humanity and God (11: 305-306; emphasis in original):

(The earth} at last returns into herself, assuming a form that allows her to meet God face-to-

face. . . . Here earth knew heaven and was known by it. Here both facets of creation, the

Divine and the extradivine, the upper and the lower, indeed become one: they actually unite

and possess a conscious sense of that union. For in truth itis possible to know one another

‘oniy in a real union: perfect knowledge must be realized, and real union must be idealized

in order to become perfect. That is why union, and in the main the union of the sexes, is

referred to in the Bible by the term knowledge,

Itis particularly telling that the knowledge of which Solov‘ev writes is arrived at face-to-

face; Solov'ev conceives of his androgynous ideal sexually. In another work discussing erotic

love, Zhiznennaia drama Platona (9:235), Solov'ey tells us that the Platonic androgyne is

united back-to-back; Solov’ev's own ideal, with Kabbalistic authority, assumes a more erotic pose.

‘The Zohar suggests a similar sexual drama (1:35a; Soncino edition, 1: 131):

‘When the fower union was perfected and Adam and Eve were tumed face to face, then the

upper union was consummated. . . . When this lower world was tumed face to face 10 the

upper, it became a support to the upper, for previousiy the work had been defective, because

“the Lord God had not caused rain to fall upon the earth."

For both Kubbalah and Solov’ev, earth and heaven are involved in a grand sexual drama,

the purpose of which is rikkun, the healing of the universe in the words of Kabbalah, ot God-

manhood for Soiov'ev. The true Godman, like the anthropomorphized sefirat as a whole, is an-

drogynous: not asexual, but potently and productively bisexual. As opposed to Grosticism, Bud-

dhism, and many Christian mysticisms, the spisitualization of mankind does not require the

elimination of the genders. Despite the Augustinian Christian tradition of western philosophy in

which he was trained, Solov'ev turns through Eastern Orthodoxy and German idealism to Jewish

theosophy in order to assert that sexuality is not the cesuit of fallen, and therefore evil, matter.

Women as well as men are members of a divine-human family, that, understood as a whole, is an

erotic, yet androgynous ideal. This is perhaps Solov'ev's closest affinity with the Jewish

Kabbalah."

33, See Idel, “Métaphores et pratiques sexuelies,"” 353~354.

You might also like

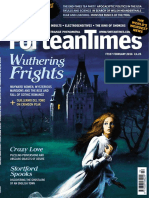

- Fortean Times - February 2016 PDFDocument84 pagesFortean Times - February 2016 PDFkingkrome999100% (2)

- Pseudo-Ephrem - On The Antichrist and On The End of The WorldDocument27 pagesPseudo-Ephrem - On The Antichrist and On The End of The Worldkingkrome999No ratings yet

- Brothers of The Free SpiritDocument2 pagesBrothers of The Free Spiritkingkrome999No ratings yet

- Fragments From ReimarusDocument135 pagesFragments From Reimaruskingkrome999No ratings yet

- The Descent of Ishtar, The Fall of Sophia, and The Jewish Roots of GnosticismDocument33 pagesThe Descent of Ishtar, The Fall of Sophia, and The Jewish Roots of GnosticismNathan HolzsterlNo ratings yet

- Rex MundiDocument2 pagesRex Mundikingkrome999No ratings yet

- Brethren of The Free SpiritDocument1 pageBrethren of The Free Spiritkingkrome999No ratings yet

- James Kelhoffer - Basilides's Gospel and ExegeticaDocument21 pagesJames Kelhoffer - Basilides's Gospel and Exegeticakingkrome999No ratings yet

- Four Kingdoms of DanielDocument55 pagesFour Kingdoms of Danielkingkrome999No ratings yet

- Oligarchy - Black NobilityDocument22 pagesOligarchy - Black Nobilitykingkrome999No ratings yet

- $JES102 Basics of Jainism E1 20071203 000111Document96 pages$JES102 Basics of Jainism E1 20071203 000111Sanjay JainNo ratings yet

- L. Rabinowitz - The First EssenesDocument4 pagesL. Rabinowitz - The First Esseneskingkrome999No ratings yet

- Amy Scerba - Changing Literary Representations of LilithDocument183 pagesAmy Scerba - Changing Literary Representations of Lilithkingkrome999No ratings yet

- Albert Henrichs - Greece in RomeDocument20 pagesAlbert Henrichs - Greece in Romekingkrome999No ratings yet

- 1962 GreenbergDocument6 pages1962 Greenbergkingkrome999No ratings yet

- Myth, Allegory and Argument in PlatoDocument21 pagesMyth, Allegory and Argument in Platokingkrome999No ratings yet

- Heard and Unheard Strophes in The Parodos of Aeschylus' Seven Against ThebesDocument7 pagesHeard and Unheard Strophes in The Parodos of Aeschylus' Seven Against Thebeskingkrome999No ratings yet

- Hesiod and Parmenides in Nag HammadiDocument9 pagesHesiod and Parmenides in Nag Hammadikingkrome999No ratings yet

- Genizah FragmentsDocument29 pagesGenizah Fragmentskingkrome999No ratings yet

- Semite and AryanDocument2 pagesSemite and Aryankingkrome999No ratings yet

- Ancient Blacksmith, The Iron Age, Damascuc Steel, and Modern MetallurgyDocument7 pagesAncient Blacksmith, The Iron Age, Damascuc Steel, and Modern Metallurgykingkrome999No ratings yet

- The Birth of Monotheism, by André LemaireDocument3 pagesThe Birth of Monotheism, by André Lemairekingkrome999No ratings yet

- The Platonic Sage in LoveDocument8 pagesThe Platonic Sage in Lovekingkrome999No ratings yet

- Fumiaki Nakanishi - Possession - A Form of ShamanismDocument9 pagesFumiaki Nakanishi - Possession - A Form of Shamanismkingkrome999No ratings yet

- Rubio, Gonzalo - On The Alleged Pre-Sumerian SubstratumDocument17 pagesRubio, Gonzalo - On The Alleged Pre-Sumerian Substratumkingkrome999No ratings yet

- Shamanism and WitchcraftDocument9 pagesShamanism and Witchcraftkingkrome999100% (1)

- Baines 1975 Ankh Belt SheathDocument25 pagesBaines 1975 Ankh Belt Sheathkingkrome999No ratings yet

- Emma Wilby - Burcharda's Strigae, The Witches' SabbathDocument33 pagesEmma Wilby - Burcharda's Strigae, The Witches' Sabbathkingkrome999100% (2)

- Nissinen 2001Document45 pagesNissinen 2001kingkrome999No ratings yet

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (120)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)