Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Scientific American

Scientific American

Uploaded by

Diana Ioja0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

17 views13 pagesScientific American

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentScientific American

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

17 views13 pagesScientific American

Scientific American

Uploaded by

Diana IojaScientific American

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 13

aq

is material may be protected by

Copyright law ie 17 0.8. Code).

n the building of his shelter primitive

mau faces one supreme and absolute

tation: the impact of the environ.

iment in which he finds himself must be

met by the building materials which

that environment afvords, Th

ment iy searcely ever genial, and the

building materials are often appallingly

meager in quantity or restrited in kind,

‘The Eskimo has only snow and ice; the

Sudanese, mu and reeds; the Siberian

herdsman, animal hides and felted hair;

the Melanesian, palm leaves and bam:

boo. Yet primitive architecture reveals

a very high level of performance, even

when judged in the light of madera

technology. It reflects « precise and de

tailed knowledge of local climate con-

ditions on the one hand, and on the other

a remarkable understanding of the per

formance characteristics of the building

materials locally available.

OF course primitive architecture, like

primitive me

icine or primitive agricul

ture, often has a_magico-religious ra

tionale that is of interest only to anthro

pologists, But its practice—that is, how

things are done, as distinct from the rea-

sons offered for doing them-is apt to be

sumprisingly sensible, (This illogical

situation is characteristic of prescientific

technologies: the Roman architect Vite

vis, writing during the reign of Augus

tus, gives excellent formulas for concrete

and stucco, but his explanation of their

chemistry” makes no sense at all.) The

primitive architect works in an economy

of scarcity-his resources in materials

and energy are severely restricted. Yet

hie has little margin for error in coping

with natural forces: gravity, heat, cold

wind, snow, rain and flood. Both his

theory and his practice are strictly deter-

mined by these conditions

An understanding of this primitive

by James Marston Fitch and Da

Despite meager resources, primitive people have designed dwellin

se > P P 8

shelters often outperform the structures of present-day art

ustrialization and urbanization of the

Western world, there is a growing tend.

tency to minimize or ignore the impor-

tance and complexity of the natural en-

Vironment. Not only is the modern arch

tect quite removed from any direct

experience with climatic and geographic

cause-and-effect; he is also quite per

suaded that they “don't matter any

more.” Yet the poor performance of most

moder buildings is impressive evidence

to the contrary. Many recent buildings

widely admired for their appearance ac-

tually function quite poorly. Many glass

walled New York skyscrapers have

leaked badly during rainstorms, and

hhave had to be resealed at large cost

The fetish of glass walls has ereated fur-

ther problems. The excessive light, heat

and glare from poorly oriented glass

places insuperable loads on the shading

and cooling devices of the building—a

problem that is often compounded in the

winter when the air-conditioning ma-

chinery is turned off [see “The Curtain

Wall," by James Marston Fitch; Sctes-

uric AneeRicax, March, 19.

‘Thus Western man, for all his im

pressive knowledge and technological

apparatus, often builds comparably less

well than did his primitive predecessor

A central reason for his failure Ties in

consistent underestimation of the en:

Vironmental forces that play upon his

buildings and cities, and consistent over

estimation of his own technological ea-

pacites. Stil, the worst he faces is a dis.

satisfied client. When the primitive

architect errs, he faces a harsh and) une

forgiving Nature,

A, £00 definitions are pert in order.

£V As used here, the term “primitive”

describes the buildings of preliterate so

cieties, whether historical or current,

Primitive Architecture and Climate

es

that successfully meet the severest climate problems. These simple

phitects |

cl P, Branch

prenticeship, whose industry is hand

craft and whose tools are pre-Tron Age

Although the folk architectures of mod: |

erm civilization often display the same |

kind of pragmatic sagacity as the primi

tive, they are of a qualitatively diferent

order. The iron tools and the measure

ment systems of civilization immediately

introchice factors such as modular build:

ing material (e.g., brick, tile, dimen

sioned lumber) and repetitive structural

systems (eg

{

|

|

Roman cade, vaulted

Gothic bay) which ae antithetical tothe |

plhsticty of primitive structure Lite.

fey, on the other hands intxtces the

dlaconcerting concept of a spectrum af

Duslding stylesman Tnconceivable sits

tion tothe primitive architect, to whom

it has never occurred that there is more

than one way to build. It is obvious that

changed ad evolved gradually aver mi

Tenn, but at any given tne he print

lve architect was spared this unrecorded

and forgotten history of styles, Indeed,

Inowledge of prehistoric architecture

as exprened in ordinary humble vel

ings. 30 scanty that tis rte il

deal almost eattely with examples of

Primitive dvellings sill being bule

tious parts of the word

As used here, the tem "performance

rciers tothe actal physi! behavior of

the building in response to environmen:

tal stresses, whether they be mechanical

(snow load, wind pressure, earthquake)

‘or purely physical (heat, cold, light)

Civilization demands other sorts of

performance from its architecture, but

those faced by the primitive architect are

basic and must be satisfied before more

sophisticated performance is possible

For the purposes of this discussion we

are not concerned with plan, that is, the

shape, size, seale or compartmentation

experience is of more than academic in- whose general knowledge comes by _ given to architecture by problems of so. oe

ferest today because, with the rapid in- word of mouth, whose training is by ap- cial exigency or cultural convention. For ara

134

‘Twy THATCHED HUT:

the

north of th

+ wsnsivestryeture 66 shsorb the intone salar fet he: hte are

‘of adobe finite on 9 maid cock fovndasion, hich prosecte thems

from the waner that youre slows the hillsides when it raina

3

ccample, the exigeney of organized war-

fave would adel s moat and a wall to one

piou, and the convention of polygamy

vould introduce a harem into another,

Nether will have any significance except

in relation to the culture that gave it

hth. The significance of architectural

structure, on the other hand, fs absolutes

anf either supports load of snow oF

itellapsess a wall either stands up to the

vind or it falls. Even the simplest buat

oil have a plan, just ay the most primi-

tive society will have its taboos and con=

vwolions. But the simpler the plan re-

sqtements of a building, the clearer will

Leits aspect of environmental response,

V[ber se contemplate the work's

enormous range of temperature and

presipitation, whose summation largely

Aesribes climate [see illustrations at

righ and at top of pages 138 and 139),

wemust be imprested by man's ingentc

i. OF these two chief components of

liste, it is heat and cold that present

theprimitive arehitect with his most dif-

feat problem, In culture after culture

the solutions he has found show a sur-

pring delicacy and. precision, Since

thamal comfort is a finetion of four

scurate environmental factors (ambient

and adiant temperatures, ar movement,

fumidity), and since all four ace in con

sant fs, any precise architectural m

niulation of them demands real analytic

abity, even if intutive, on the pat of

the designer. In the North American

Actc and in the deserts of Ameria, AL-

nea and the Middle Bast he has pro-

faced two classic mechanisins of ther-

rl control: the snow igloo and the

smdwvall hut

Ona purely theoretical basis it would

le hard to conceive of a better shelter

aust the aretie winter than the igloo.

1b excellent performance is a function

6t both form and material, The hemi-

spherical dome offers the maxim es

tince and the minimum obstruction to

winter gales, and at the same tine ex-

goses the least surface to their chilling

tect. The dome hus the Further merits

of enclosing the largest volume with the

smallest stricture; at the same time it

yields that volume most effectively heat-

ed by the point souree of radiant heat

alfred by’ a ol lamp.

The infense and steady cokd of the

Arete dictates a wall material of the

lowest posible heat capacity: dy snow

tneets this eriterion admirably, though

at frst glance it seems the least likely

structural material imaginable. The

Eskimo has evolved a superb method

of building. quite strong shell of it

composed of snow blacks (each seme 18

136

iches thick, 36 inches Ton soul six

inches high) laid in one continuous, in

sloping spiral. The insulating value of

{his shell is further improved by a glaze

df ice that the heat of an il lamp and

the bodies of occupants automatically

add to the inner serface. ‘This ive film

seals the tiny pores in the shelf and, like

cumare

ARCTIC AND SUBARCTIC

(CONTINENTAL STEPPE

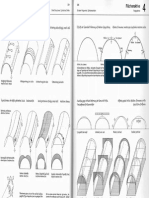

IMPACT OF CLIMATE and available building materials on the design of primitive dwell:

in this char. It deseribes the Four l

ye found,

ings 1 sume

‘variety of primitive architertare ist

the aluminum foil on the

1 wall insilation

heat reflector. When, finally, the Eskimo

rapes the interior of his snow shell with

furs, thereby’ preventing the

chilling of his body by either radian

tive heat loss to the cold floor and

walls, he has completed an

skins

cond

nthe first

ner face of

netsasa radiant=

of next

nostril,

thing t

a small

of the

matter,

almost per-

‘Hemiat crawacrenisrics | PECURED At

‘e5FC

INTENSE, CONTINUOUS COLD oy HEAT CAP»

LUTTE SOLAR UGHT OR Hear [ND ROOF

wc wn IMUM SURF

ae MUM STAB

SUM

MODERATE TEMPERATURES

INTENSE SOLAR RADIATION. fics HEAT CAP:

D WAUS

WINTER

InsINSe, CONTINUOUS COLD

NEGUGIBLE SOLAR HEAT

HEAT CAP»

10 ROOF

Coes iNIMUM PO:

MUM STAB

sumer

LONG, WARM DAYS (ADE, VENTIA

cob NIGHTS HEAT CAP

LUTTUE 08 NO SEASONAL VARIAT

HOT DAYS-COLD NIGHTS

INTENSE SOLAR LIGHT AND He

VERY LOW HUMIDITY

ume ean

INO SEASONAL VARIATION,

pouon HEAT CAPA

WARM NIGHTS IND ROOF

INTENSE SOLAR RADIATION stag

HGH Hummes cUM VENT

HEAVY RAINFALL

of tem

where the greatest lary

ree elimate zones, control the pe

col

with

the

stor

and

repsrics

us cow

RES

‘anon

ss cow

fect instrument of control of his thermal

cqvironment [see illustration at bottom

of next page]. For the civilized Western

nostril, the ventilation may leave some:

thing to be desired (it usually consists of

small opening somewhere near the top

the igloo). But odor is a subjective

smatter, and the oxygen supply is ade-

URED ARCHITECTURAL

SPONSE "AVALA

at CAPACITY WALLS

100F

yO SUREACE,

1 STABLITY

snow

HEAT CAPACITY ROOF

alls

EAT CAPACITY WAUS

3008

AN EXPOSED SURFACE

AM STABLITY

RAW MATERIALS

TURF, EARTH, DRIWOOD

quate for breathing and keeping the oil

lasnp alight.

Nonnally the glo is a temporary

structure, Like most primitive architec-

ture, it sacrifices permanence to high

performance. The wife of the noted ex-

plorer Vilhjakmur Stefansson, Evelyn

Stefansson, reports on one that she ob-

‘TYPE OF TENANCY

i SEASONAL

(HUNTING)

SEASONAL

| GUNTINGRSHING)

roma ren smn

served. The inside walls began to drip

when the outside tempera

degrees Fahrenheit,

collapsed the next

ay, when the tem-

perature rose to 39% degrees F, and it

‘began to rain. But the Balfin Land Eski-

ros build permanent igloos of several

units, connected by vaulted tunnels and

STRUCTURAL SYSTEM EVOLVED

SNOWOOME, ICE-AND FURLINED

2 Ny

IDE AND FELT MEMBRANES ON FRAME

ANAL SEINE KAR nowoie

pais | ONE)

fp vNATion

ea CAPACITY WALLS

coe

Lvanario

as | HEAT CAPACITY ROOF

‘AND HEAT #BWAILS

wo, stones renwaneut

IM VENTILATION. REEDS, PALMS, SAPLINGS AGRICULTURE)

NATEBROOF |

sa0N : : |

HEAT CAPACITY Ws |

|

cron fin sane ‘ss, st€08, soo, souanent |

Nemanon | PAUAFIONDS, FOURS” | CAGHEUTUR, BANG) |

i |

i | |

\ | |

|

all of temperature is the crucial architectural problem. In the fourth

tet teary lcasnal Flay tothe dificalty, To solve be pebleme

trol ‘the primitive architect shrewdly ¢ ‘the limited materials ment

SOUD, LOAD-BEARING MUD.MASONRY WALLS

ROOFS; MUD CEMENT ON WATTLE

OLE OR PALM TRUNK RAFTERS

SKELETAL FRAME, THATCHED ROOF, WALS

SLOPING PARASOL ROOF

STLTED FLOORS,

available to him and works them into a structural form that ad-

mnirably meets both the demands of the climate and the require

ot his particular culture: noma

CLIMATE MAP identifies seven principal regions all once oe:

imitive man, He fis now heen largely pushed out of

caied by

aislocks to subsidiary units for food stor=

age, dogs and equipment. In any ease,

the igloo melts no sooner than the Eskimo

isready to discard it, It dids’t take him

Jong to build, and it gives him first-class

prnteetion while st lasts

[fore eam to quite another type of ther

ial regime, that of the great deserts

of the lower latitudes, we find an archi-

tectural response equally appropriate to

radically different conditions. Here the

characteristic problem is extremely high

daytime temperatures coupled w

comfortably low temperatures at night

Sometimes, a¢ in the U. S. Southwest,

wide seasonal variations are superim:

posed upon these diurnal ones. Against

such fluctuations the desirable insula-

tion material would be one with a high

hheat-eapacity. Such a material would

absorb solar radiation during the day-

Tight hours and slowly reradiate it dur-

ing the night. Thus the diurnal tempera-

ture curve inside the building would be

fattened out into a mich more eomfort-

able profile: cooler in daytime, warmer

138

at night [see dlustration at bottom of op-

posite page]. Clay and stone are high

hheat-capacity materials; they are plenti-

fal in the desert, and it is precisely out

of them that primitive folk around the

‘world make their buildings, Adobe brick

and terra pise (molded earth) as well as

TomeRaTUne (OEGREES F)

6AM NOON

cen sae rewrsnaTune)

the two most genial elimate zones

‘Thus the primitive architet, where fe ail exists hn 80 cope with

he temperate and subteopieal

mud and rubble masonry, appear in the

Southwest; massive walls of sun-baked

brick in Mesopotamia; clay mortar os

reed or twig mesh in Afriea from the

Nile Delta to the Gold Coast. And the

native architect evolves. sophisticated

orm, ‘MONIGHT oaM

= SLEEPING PLATFORM,

Sno uve

= oursioe renwerarune

ICLOO TEMPERATURES may rum as much a8 65 de-

srees Fabrenheit higher than external sir temperatures.

‘The heat source: a few oil lamps and a few Eskimo

bodies. Outside temperature is typical

more di

confront

ment. 1

wind, #

around

mornin

Where

benches

shaded

J

v0

&

TOMPERATURE (DEGREES F)

jemi

fn the

aked

fs the

fd the

sted

confronting the average modern architet.

ment. Here, to avoid a sharp winter

wind, the entrance door will be moved

tound to the lee; there, to get early

‘moming solar heat, i will face the east,

Where aftemoons’ are cool, dooryard

benches face the west; where hot, the

shaded east

—— ROOF SURFACE

— outst reveezarure

SUBARCTIC. AND TUNDRA

(CONTINENTAL STEFFE AND CESERT

Teeeeare

SUBTRORCAL

LOW LATITUDE STEFFE AND DESERT

PAINFORIST AND SAVANNA

HIGHLANDS.

Limited to what for us would be &

pitifully meager choice of materials, the

primitive architect often employs them

so skilfully as to make them seem ideal.

‘Africa, for example, has developed

dozens of variations of the structural use

of vegetable bers (grasses, reeds, twigs,

saplings, palm trunks) both indepen.

dently and as reinforcement for mud

masonry. In Egypt, where it seldom

rains, fat roofs are practicable; hence

mud walls carry palm-teunk roof beams

which in turn support a mud slab rein:

forced with palm fronds. Other regions,

although arid, will have seasonal rains;

here sloping forms and water-shedding

surfaces are necessary. The beautiful

beehive hut appears. Bui like a conical

basket on an elegant frame of bent sup-

Tings and withes, the beehive hut is

sometimes sheathed with water-repellent

thatch; sometimes mud plaster is worked

into the wattle; sometimes the two are

combined, as in the huts of the Bauchi

Plateau of Nigeria

‘The Nigerians construct a double-

shelled dome for the two seasons. ‘Th

inner one is of mud with built-in pro-

jecting wooden pegs to receive the outer

shell of thatch. An air space separates

ona MONGHT o AM.

ADOBE HOUSE TEMPERATURES compare favorably |

‘with those obtainable ia modern aircon

oned homer.

Moreover, the solar heat trapped by the roof slab in the

daytime keeps the interior warm through the chill night.

INSIDE TEMPERATURE

Modern

BURGESS BATTERIES

CHROME PROTECTED

SEALED-IN-STEEL

SELF RECHARGEABLE

GUARANTEED LEAKPROOF

Faden bights

CORROSION PROOF

reporated head ond

‘otery design

BURGESS BATTERY COMP)

DEPARTMENT OF

SCIENTIFIC AND

INDUSTRIAL RESEARCH

invites applications from young Bitsh

honours graduates in scionca and tock

nology at prvart in North Amarice for

doctoral

NATO SCIENCE

FELLOWSHIPS

tenable in UNIVERSITIES, COLLEGES

‘AND OTHER APPROVED LABORA.

TORIES IN THE

UNITED KINGDOM

Further datatle may be obteined from

UK SM, 1907 K Stoo, NW, Wash

ington 6, D.C, to whom all applica

tions should be sont by let January

1961

139

the two, This construction accomplishes

three things: the thatch sheds water and.

protects the clay dome during the rainy

season; the air space acts as additional

insulation dnring hot days and the mud

dome conserves heat for the cool nights.

The principle of reinforcing is well

understood. The Ashantis of West Africa

build truly monolithie structures of mud

beaten into a reinforcing web of woven

bovigs. Moreover, we find that the mass

of the wall is adjusted to meet varying

temperature regimes. In the colder des:

cert areas the walls will be very thick to

inerease their heatholding capacity,

Often, in fact, to benefit from the more

stable earth temperatures, the houses

will be built into a southern elif face

(U.S. Southwest, southern Tunisia

Shensi province in'China). In. warmer

desert regions, where diurnal oF seasonal

variations are smaller, the wall mass can

be greatly reduced by the reinforcing

techniques deseribed above, In these

gions, too, intense radiation and glare

are the source of discomfort. Here again

we find the primitive architect alertly

responsive, Door and window openings

are rechced in size to hald down interior

light levels, and walls are painted or

stuccoed white to reflect a maximum

amount of radiant heat.

TT[hs inner topical zones of the earth

confront the primitive architect with

quite another set of comfort problems

Here heavy rainfall and high humidity

are combined with moderate air temper-

atures and intense solar radiation, There

and very litte diurnal,

perature, Thus. shade

and maximum ventilation are the eritical

components of comfort. To reduce the

heatcholding capacity of the walls and

to maximize the aie flow across the in-

terior, the primitive architect reduces the

wall fo a minimum, or gives it up alto:

gether. The roof becomes the dominant

Structural element: a huge parasol,

steeply sloping to shed torrential rains,

‘opaque to solar radiation and of mini.

‘mm mass to avoid heat build-up and

subsequent reradiation into the living

space. This parasol roof usually extends

far beyond the living space to protect

the inhabitants against slanting sun and

blowing rain, And the floors af these airy

pavilions are sometimes raised on stilts

for better exposure to prevailing breezes

as well as for protection from snakes,

rats and crawling insects, This is the

basie architectural formula of the Semni-

roles of Florida, of the tribes of the

Caribbean littoral and of the Melanes

ans, The materials employed are pre

variation inter

M40

dominantly vegetable fibers of all sorts

saplings and bamboo, vines for lashing

them together, shredded fronds and

grasses, In the absence of iron tools the

cutting and fitting of earpentry is totally

missing; instead the techniques of as

sembly are the tying and weaving of

basketry or textiles, Here again, from the

point of view of environmental response,

the primitive designer shows an acnte

‘understanding of the local problem and

a precise understanding of the proper

ties of local materials

Tn the outer tropical zanes other re

fnements appear. Here the climate is

characterized by two distinct seasons:

PRIMITIVE DWELLINGS, viewed as engineering structures, extract remarkably hish per

formance from commonplace materials. Eskimo igloo (a)

ek that have insulating value equivalent to tw

inches

without melting the dome. Summer house of Nanos

baile from snow blocks 18

are ho

ployed

achiew

heat a

in Sou

woode

mats. 1

‘but ie ma

tent (eh,

Its light

a

Fane pee very wet and one very dey. (Both in dey weuther,permiting the move- Naturally many athe forces beyond

ind ABP*e bot) Vegetable fibers are sll em ment of alr through its interstices, ot the purely climate ave at work in shap-

phyed, but in varying techniques, to the Abts expand in wet weather, con- ing primitive archtecare. The. etre

steve a wide range of permeability to. verting. them ito. nearly waterproof andmeans.of subsistence wil deter

Seatand air. Thus certain tres of Natal membranes. Inthe huts of the Khesion nine whether the shelter e permanent,

South fica buld a hot whose ight tribe of South fica these ats are de- mobile, seasonal or purely temporary I

ronden frame is sheathed in woven ber tichable ml can be moved Irom wall to the vulture fsa hunting oe, ie that of

mals The weave of these mats contracts wall according to wind tection. the Indians. who once. inbabted. the

per

ite is

teat (el, fs among the most ingenious and ws ‘of tepee shows

‘uiny types of demountable diel the three poles (solid cirles) th st. Bedouin tent

ls lightweight willow walls fold up like a childs safety gate. The (e), urually of woven goat hair, shade, but, when

covering is felt, sometimes twosayered with an aie space between, required, mut serve as a pro st sandstorm,

4h

Great Plains of North America; ot a

herding one, like that of the peoples of

the Asiatic steppes, the architecture will

tend to be demountable and mobile. But

it will not be expendable, because suit-

able building materials are not readily

available on the open steppe or prairie

(The sod dugout would make sense only

‘TROPICAL DWELLINGS, including one for temperate climate,

reflect a great disperity in +0 jon, but all are effective shel-

ters. The adobe house (f) of Indians of the Southwest i built of

Baked mud bricks with a smooth mudplaster exterior. The massive

roof is ideally designed to absorb the midday heat. The Navajo

142

material," the tent (like all tension struc-

cloth. }

fn a permanent settlement.) Hence the tures) ranks as a very advanced form ol HB Sythe

structurally brilliant invention ofthe tent construetion. ‘The basie type has been WE (clone

“light in weight, composed of small modified to meet a wide variety of cl: FP the den

members and easily erected, disinantled mates: The Ametican Indians covered HF tion is

and packed, At the same time, if we the skeleton with skinss the Australian JE Gver th

judge it by the modem structural crite- aborigines, with bark; the nomads of FF Ye a

rion of “the most work from the least northern Asia, with felted hatr; the no FB taxed

ads of the Middle East, with woven

heat (a) wath ode rmitng el aed ede PS

reat Wooten tame The ane ited ene han mec le

Fathnpc hr (sink Pyne notes Coo

oe,

tected by the deep shade of the forest it does not need masine

ost.)

Congo)

leis pro:

th. Perhaps the most advanced form,

Inthe bitter cold of Siberia, was that de

swhped by the Mongol herdsmen. Here

the demand for effective thermal insula-

tion is met by two layers of felt stetched

wer the inside and outside of a collapsi

be wooden trellis. The elliptical dome,

staked to the earth, furnishes excellent

leatabsorbing walls and rool. The Chippewa hut (3) closely re

pt that itis covered with bireh hark.

‘against the weather characteristic of the

The Seminole Indian house (j) antick

ies <0 admired by today’s civilized

senbles the Pygmy bs

protection against the high winds and

bitter cold of Siberia,

(ts sould extend this eatalogue of

human ingenuity indefinitel

the examples cited are surely adequate

to establish the basic point: that prim

tive man, for all his scanty resources,

rn

Inn

My

often builds more wisely than we do,

and that in his architecture he estab-

lishes principles of design that we

ignore at great cost. It would be a mis

take to romanticize his accomplishinents

With respect to civilized standards of

amenity, safety and permanence,

tual forms of his architecture are

Florida dwellers. In the Lake Chad region of Africs the local tribes

Duild a eylindrical adobe hat (k) with a conical thatehed root

‘This roo, lke that of the st

off New Guines, i most effective in shedding rain, In World War IL

the Pacific troops found such roofs much drier then a tent

house (1) of the Admiralty Islands

143

totally unsuitable, Neither is there any

profit in the literal imitation of his hand

craft techniques ot in the artifical ve

striction of building materials to those

locally available. Primitive architecture

merits our study for its prineiples, not its

forms; but these have deep relevance

for our populous and il-housed world.

If we are to provide adequate hous

for billions of people, it cannot be on the

extravagant model of our Western tbs,

suburbs andl exurbs. The cost in building

materials and in fuels (for both heating

and cooling) would be altogether pro:

hibitive for the foreseeable future.

‘Wester science may be able to meas

sire with gre

mental forces with which architecture

deals, But Western technology—especial:

ly modern American technology too of

accuracy the envitos:

PUEBLO

zw

with thatched huts built

M44

JU KRAAL in Union of South Afriea answers elim

‘woven framework of Hight branches

ten respondls with the mass production of

a handful of quite clumsy stereotypes.

This is obvious, for example, inthe ther

‘mal-control features of our architecture

In the house or the skyseraper, gener

speaking, we employ’ one type of wall

and one type of roof. The thermal char=

acteristics of these membranes will be

roughly: suitable to a thermal regime

such as that of Detroit. Yet we duphieate

them indiscriminately across the coun:

try, in climates that mimic those of Scot

land, the Sahara, the Russian steppes

and the subtropies of Central America

The basie inefficiency of this process is

masked by the relative cheapness of

fuels and the relative efficiency of the

‘equipment used to heat, cool and venti

late our buildings. But the social waste

of energy and material remains,

INDO-CHINESE. V

SOUTH SEA VILL

Parasol constr

problem

Contemporary U.S, architecture

would be greatly enriched, esthetically

as well as operationally, by a sober anal

ysis ofits primitive traditions. Nor woul

ithe stretching things to include in these

traditions the simple but excellent archi

tecture of the early white settlers who, i

many respects, were culturally closer to

primitive man than to 20th-centary man.

The preinslustrial architects of Colonial

and early 19th-century America pro:

duced designs of wonderful fitness: the

snug, well-oriented houses of New Eng.

land, the cool and breezy” plantation

houses of the deep south, the thick

walled, patio-centered haciendas of th

Spanish Southwest, AID these designs

should be studied for the usefulness of

their concepts, and not merely be copied

for

ntiquarian reasons,

TLLAGE illuste

AGE on Alor Island near Borneo shows lish

mm x0 admirable For regions of heavy rainfall

Totally usable, Neder & twee any

Profi fo the Btor imitation of his hued

Grnft teckmiqnes or hy the artificial re

ing materials to those

extir

merits our studly for its principles, not its

forms; bot these have deep relevunce

for cate poputons

loca

Is and in duels (ioe both heating

architectare

ican tochinology—to

PUEBLO Jo Ta

af two mpulisovied structs

Ul the Spent Gerviden jo

ten sespons sith the snats production of

4 hawt of qnite clumsy stereotypes.

This fs abvious, for example, im dhe ther

tases of oue vivhitectare

hiethe hone oe the skyscraper,

we employ one type of

of these «nema

roughly suitable to

eile

ses do

tty. in climates thar mime those of Scot

fund, the Sahara, the Russian steppes

# Detrait. Yet we duplicate

sorininately acne Che cot

0d : ‘anteal Aerie

fcloney of thas process é

reac of

of

masked by the relative

fuels and the relative ete

hen, coo) an

Contemporary U.S. architectag

seve 5 ope

ithe sretching

trol

many respents, wete alee

ppiitive nau thy eccenty

‘The prendustrisl acchitects of Colas

and early 1oth-oer :

ucedl designs of wor

is Southwest All these dul

stunk be studied for the veel nines

canted net mavely be

situa rocs

heer ise

a

et

ae

seen

ee

IxDO.CHINI

tad

| PELE KAAS fa Union of South Alsin anewers climate problem

sth thatched bake bi

VILLAGE Wsstestes how vim

ily doe wen eine ele fe

abies

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5813)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1092)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (844)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (348)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- GRIHA Good Site Practices ManualDocument88 pagesGRIHA Good Site Practices Manualankit007estNo ratings yet

- GRIHA Council - Paryavaran Rakshak Programme 2022 - Partnership ProposalDocument6 pagesGRIHA Council - Paryavaran Rakshak Programme 2022 - Partnership Proposalankit007estNo ratings yet

- GRIHA Case Studies - ISADocument4 pagesGRIHA Case Studies - ISAankit007estNo ratings yet

- Estructura ActivaDocument16 pagesEstructura ActivaMagister Architectura Tec VizcayaNo ratings yet

- Office: Energy Conservation in BuildingsDocument5 pagesOffice: Energy Conservation in Buildingsankit007estNo ratings yet