Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Decisions of Principle 4.3.6

Decisions of Principle 4.3.6

Uploaded by

PantatNyanehBurikCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Decisions of Principle 4.3.6

Decisions of Principle 4.3.6

Uploaded by

PantatNyanehBurikCopyright:

Available Formats

DECISIONS OF PRINCIPLE

4.3.6 We must not think that, if we can decide between one course and another

without further thought (it seems self-evident to us, which we should do), this

necessarily implies that we have some mysterious intuitive faculty which tells us

what to do. A driver does not know when to change gear by intuition; he knows

it because he has learnt and not forgotten; what he knows is a principle, though

he cannot formulate the principle in words. The same is true of moral decisions

which are sometimes called 'intuitive'. We have moral 'intuitions' because we

have learnt how to behave, and have different ones according to how we have

learnt to behave.

It would be a mistake to say that all that had to be done to a man to make him

into a good driver was to tell him, or otherwise inculcate into him, a lot of

general principles. This would be to leave out the factor of decision. Very soon

after he begins to learn, he will be faced with situations to deal with which the

provisional principles so far taught him require modification; and he will then

have to decide what to do. He will very soon discover which decisions were

right and which wrong, partly because his instructor tells him, and partly

because having seen the effects of the decisions he determines in future not to

bring about such effects. On no account must we commit the mistake of

supposing that decisions and principles occupy two separate spheres and do not

meet at any point. All decisions except those, if any, that are completely arbitrary

are to some extent decisions of principle. We are always setting precedents for

ourselves. It is not a case of the principle settling everything down to a certain

point, and decision dealing with everything below that point. Rather, decision

and principles interact throughout the whole field. Suppose that we have a

principle to act in a certain way in certain circumstances. Suppose then that we

find ourselves in circumstances which fall under the principle, but which have

certain other peculiar features, not met before, which make us ask 'Is the

principle really intended to cover cases like this, or is it incompletely specified -is there here a case belonging to a class which should be treated as exceptional?'

Our answer to this question will be a decision, but a decision of principle, as is

shown by the use of the value-word 'should'. If we decide that this should be an

exception, we thereby modify the principle by laying down an exception to it.

Suppose, for example, that in learning to drive I have been taught always to

signal before I slow down or stop, but have not yet been taught what to do when

stopping in an emergency; if a child leaps in front of my car, I do not signal, but

keep both hands on the steering-wheel; and thereafter I accept the former

principle with this exception, that in cases of emergency it is better to steer than

to signal. I have, even on the spur of the moment, made a decision of principle.

To understand what happens in cases like this is to understand a great deal

about the making of value-judgements.

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5807)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1091)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (842)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (346)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Italian Risorgimento-CompressoDocument4 pagesThe Italian Risorgimento-CompressoLoredana ManciniNo ratings yet

- New Text DocumentDocument1 pageNew Text DocumentCecily KnightsNo ratings yet

- Plta Semangka 2 X 28.3 MW Field Actual (Daily Activity) : Maintenance TeamDocument3 pagesPlta Semangka 2 X 28.3 MW Field Actual (Daily Activity) : Maintenance TeamNasriNo ratings yet

- My DayDocument3 pagesMy DayАлина СамусьNo ratings yet

- Unit 5 Lymphatic SystemDocument16 pagesUnit 5 Lymphatic SystemChandan ShahNo ratings yet

- Dr. Ram Manohar Lohiya National Law University: Is Us Abandoning Rules Based Multilateral International Trading SystemDocument3 pagesDr. Ram Manohar Lohiya National Law University: Is Us Abandoning Rules Based Multilateral International Trading SystemRishi SehgalNo ratings yet

- The Way of The WorldDocument2 pagesThe Way of The WorldMagda Gherasim100% (1)

- Anand Kumar Periwal (Updated Resume)Document3 pagesAnand Kumar Periwal (Updated Resume)Anand PeriwalNo ratings yet

- Managerial Accounting Canadian 2nd Edition Braun Solutions ManualDocument99 pagesManagerial Accounting Canadian 2nd Edition Braun Solutions ManualKennethSparkskqgmr100% (17)

- Soal PTS Bahasa Inggris SMK Kelas XIDocument1 pageSoal PTS Bahasa Inggris SMK Kelas XIRizal FadillahNo ratings yet

- The Beginnings of I S L A M I C Theology: A Critique of Joseph Van Ess' ViewsDocument14 pagesThe Beginnings of I S L A M I C Theology: A Critique of Joseph Van Ess' ViewsTalal MalikNo ratings yet

- Christmas in Spain Worksheet: Spanish Words TranslationDocument3 pagesChristmas in Spain Worksheet: Spanish Words TranslationMai RodasNo ratings yet

- Us and China Trade WarDocument2 pagesUs and China Trade WarMifta Dian Pratiwi100% (1)

- Consumer Behavior 10th Edition Schiffman Test BankDocument25 pagesConsumer Behavior 10th Edition Schiffman Test BankMatthewMossfnak100% (53)

- Fish RUsDocument11 pagesFish RUseia aieNo ratings yet

- CDB Vol I No. 77 (02.18.2014)Document16 pagesCDB Vol I No. 77 (02.18.2014)Christian Ian LimNo ratings yet

- Agricultural TenancyDocument20 pagesAgricultural TenancyJel LyNo ratings yet

- How To Scale An Seo Business Diggity Marketing PDFDocument22 pagesHow To Scale An Seo Business Diggity Marketing PDFsoeNo ratings yet

- HCM US Ceridian Tax Filing White Paper v7.3Document9 pagesHCM US Ceridian Tax Filing White Paper v7.3yurijapNo ratings yet

- SS 513-1-2013 - PreviewDocument9 pagesSS 513-1-2013 - PreviewalexNo ratings yet

- My Teaching PhilosophyDocument4 pagesMy Teaching PhilosophysangdeepNo ratings yet

- Livestock CensusDocument20 pagesLivestock Censusdudul samantrayNo ratings yet

- Exxonmobil 800089 340343 040909 Public Notice EnglishDocument2 pagesExxonmobil 800089 340343 040909 Public Notice Englishapi-242947664No ratings yet

- Landlord: InsuranceDocument76 pagesLandlord: InsuranceArvinder DhanotaNo ratings yet

- 32 On 18Document2 pages32 On 18Bisman shahid100% (1)

- YDS Kelime ListesiDocument34 pagesYDS Kelime Listesibilal kocabaş100% (1)

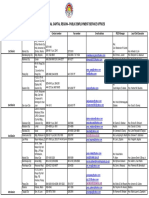

- National Capital Region - Public Employment Service OfficesDocument2 pagesNational Capital Region - Public Employment Service OfficesAnghie CastilloNo ratings yet

- Ken Dancyger - Storytelling For Film and Television - From First Word To Last Frame-Routledge (2019)Document209 pagesKen Dancyger - Storytelling For Film and Television - From First Word To Last Frame-Routledge (2019)Genaro Poma100% (1)

- Learning Task 18Document2 pagesLearning Task 18Marlhen Euge SanicoNo ratings yet

- BWPT - Annual Report - 2013 PDFDocument252 pagesBWPT - Annual Report - 2013 PDFNur NatasyaNo ratings yet