Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Herb Grossman. Multidiscipline Culture

Herb Grossman. Multidiscipline Culture

Uploaded by

Mark Contreras0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

8 views4 pagesMultidiscipline Culture

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

DOC, PDF or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentMultidiscipline Culture

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOC, PDF or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

8 views4 pagesHerb Grossman. Multidiscipline Culture

Herb Grossman. Multidiscipline Culture

Uploaded by

Mark ContrerasMultidiscipline Culture

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOC, PDF or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 4

retirement, Dr. Grossman taught courses in classroom manage-

ment in the education and special education departments at San Jose State

University, San Jose, California. He also directed the bilingual/ cross-cultural

special education program at the same institution.

ntroduction

“The population of the United States is rapidly becoming less EuroAmer-

ican. Currently, non-EuroAmericans are in the majority in the twenty-five

largest school ts in the United States. The three fastest growing groups

are Hispanics, African Americans, and Southeast Asians. As a result, fewer

students will fic the stereotype of EuroAmerican middle-class students and

fewer students will respond positively to and profit from classroom manage-

ment techniques that have been designed with EuroAmerican middle-class

students in mind.

Culturally Inappropriate Classroom Management

Many classroom management techniques that work with EuroAmerican

middle-class students ate less effective and often ineffective with students

who have been brought up by adults who have used different management

techniques with them. To avoid the problems created by using culturally

236 Classroom Management.

inappropriate management approaches, teachers require cultural sensitivity,

cultural literacy and, in some cases, attitudinal/behavioral change.

To be culturally literate is to have a detailed knowledge of the cultural

characteristics of specific ethnic and socioeconomic groups. Being sensitive to

cultural differences in general is not sufficient. In order to adapr their man-

agement techniques to the specific cultural characteristics of their students,

educators also need to have an in-depth knowledge of the specific cultures that

are represented in their classes, This knowledge is not merely about holidays,

food, dances, music, and so forth. It includes values, behavioral norms, ac-

ceptable and effective reinforcements, patterns of interpersonal relationships,

and so on. The following area few of the many characteristics that educators

ced to consider when choosing which management techniques to use with

students from different ethnic or socioeconomic backgrounds.

+ Whether they work and learn better individually or in groups

+ Whether they think their individual desires and goals are most important or

that they should usually submit to the will and welfare of the group

+ Whether they function better under cooperative or competitive situations

+ Whether they a

+ Whether they respond better to impersonal rewards like toys, candy, time-off,

or personal rewards such as praise, smiles, and pats on the back

ferent or responsive to praise and criticism from others

+ Whether they prefer formal or informal relationships with adults

Cultural literacy can help educators avoid many types of classroom manage-

ment problems. Uninformed teachers may misunderstand students’ behavior

and try to salve problems that do not exist. For example, they may think that

students brought up to not be assertive ot to volunteer their opinions unless

encouraged to do so by adults are insecure or lacking in self-confidence and

try to remediate their “problems.”

They may also fail to notice problems that do exist. Teachers who are not

tuned in to the nonverbal ways students from different cultures communicate

may miss a request for help ora signal of distress from students who commu

cate their needs in subtle and indirect ways. And they may use culturally inef-

fective techniques to deal with problems. This can occur if they use individual

rewards to motivate a student who identifies with the group and is uncom-

fortable with individualistic approaches. It can also happen when the use of

public reprimands, writing student’s names on the board, and so on, backfire

because they cause students greater loss of face than they are able to tolerate.

Teachers who do not agree that they need to be culturally literate when

working with a group of ethnically and sociocconomically diverse students

will have to change their attitudes about how to deal with the diversity among

238 Classroom Management

resenting an effective lesson goes a long way toward thwarting potential

SRE problems

In order to “do a Madeline Hunter lesson,” teachers have to include a

number of specific steps that enable them to make deliberate and appropriate

decisions based upon the best psychological research available. Thus, a teacher

is cast in the role of a profesional decision maker—one who makes decisions

by turning to a recognized body of pedagogical knowledge. Included in a

Hunter lesson are, among other steps,

‘+ establishing an anticipatory set

+ defending why the objective(s) is important

+ teaching the lesson’s main concepts

+ checking students’ understanding

+ providing guided and independent practice

For successful teachers, a Hunter-type lesson offers little that is new or

unique. These teachers have been doing these steps intuitively. Bur, intuition,

alone, is insufficient as a widespread basis for professional decision makers.

Instead, Hunter helps teachers see the psychological basis, the pedagogical

logic, and the educational justification behind each of her recommended

steps. Thus, teachers become and, more important, feel confident in what

they are doing and ready and able to explain why they are doing what they

are doing. Further, the steps in a Hunter-type lesson provide the basis for

successful mentoring or coaching of new and/or less experienced teachers by

administrators, supervisors, and more experienced colleagues.

“The very structure recommended by Hunter that so many teachers have

come to depend upon, on occasion, has come under challenge. Some edu-

cators see a Hunter-type approach as too rigid, too mechanical, and, often,

too mandated. Hunter responds by defending what she calls a “professional

researched-based” approach to teaching rather than the more common “trial

and error” approach practiced by too many teachers. Further, she claims that

there really is no such thing as a Hunter-type lesson, adding that even wid

the steps dictated there is a good bit of teacher flexibility.

Although Hunter's recommendation that teachers apply sound psycholog-

ical principles of learning when creating lessons helps, in itself, to prevent

behavior problems, other Hunter ideas more directly address the subject of

discpling For instance, in an article titled “Do your words get them to think?”

(1985), Hunter and coauthor Bailis identify a number of classroom situations

where the way a teacher responds can contribute to student think stoppers ot

think starters.

Other Noted Authors 239

Think toppers are diect commands issued by the teacher. They place all of

the responsibility upon the teacher's shoulders for eliciting a specific (ie., the

teacher’) response from the student. Think steppers are a form of

where little or no potential for the development of student self-control exists.

Usually it results in a teacher-scudent test of wills.

Think starters, on the other hand, “not only encourage a student to think:

but indicate that you expect him to think and make decisions” (Bailis &

Hunter, p. 43). As an example, the authors offer the classroom situation

where one student is making disruptive noises while another student is trying

to speak. A think stopper teacher response might be “Be quiet!” A think starter

teacher response might be “Peggy, find a place where you can do a good job

of listening. Thanks.”

To learn more about Madeline Hunter’ ideas, read Hunter, M. (1994).

Mastery Teaching, Bailis, P., and Hunter, M. (1985). “Do your words get

them to think?” and Brande, R. (1985). “On teaching and supervising: A

conversation with Madeline Hunter.”

SPENCER KAGAN: WIN-WIN MANAGEMENT

Spencer Kagan, Ph.D.., is a former clinical psychologist and professor of

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5807)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1091)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (842)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (346)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Holy Foolishness in Russia NewDocument456 pagesHoly Foolishness in Russia NewAnonymous GfnJE2v100% (1)

- SBM Checklist For TeachersDocument2 pagesSBM Checklist For TeachersMark Contreras75% (4)

- Rubric For Ad CampaignDocument2 pagesRubric For Ad CampaignMark Contreras100% (1)

- Referat SpaniaDocument2 pagesReferat SpaniaStefanSiRoxana50% (2)

- Cultural Comparision of The Us With Germany South Korea and JapanDocument19 pagesCultural Comparision of The Us With Germany South Korea and Japanapi-313630382No ratings yet

- Mapping The Terrain - New Genre Art Public Suzanne LacyDocument24 pagesMapping The Terrain - New Genre Art Public Suzanne LacyStéphane Dis100% (2)

- Table of Specification in Science 7: Pantay National High SchoolDocument3 pagesTable of Specification in Science 7: Pantay National High SchoolMark Contreras100% (1)

- School ID School Name: School Form 1 (SF 1) School RegisterDocument83 pagesSchool ID School Name: School Form 1 (SF 1) School RegisterMark ContrerasNo ratings yet

- Structure of EnglishDocument25 pagesStructure of EnglishMark ContrerasNo ratings yet

- Telling Time: A: What Time Is It? B: 7:00Document5 pagesTelling Time: A: What Time Is It? B: 7:00Mark ContrerasNo ratings yet

- Regional Memorandum No. 159 s.20161Document63 pagesRegional Memorandum No. 159 s.20161Mark ContrerasNo ratings yet

- 01 Quiz 1Document1 page01 Quiz 1Mark Contreras50% (2)

- Picture Sounds!: Nature and Elements of CommunicationDocument2 pagesPicture Sounds!: Nature and Elements of CommunicationMark ContrerasNo ratings yet

- A Good and Smart School: Maricar Gustilo-De Ocampo June 11, 2013Document14 pagesA Good and Smart School: Maricar Gustilo-De Ocampo June 11, 2013Mark ContrerasNo ratings yet

- Beadle SheetDocument3 pagesBeadle SheetMark ContrerasNo ratings yet

- Practicing SLDocument14 pagesPracticing SLMark ContrerasNo ratings yet

- IRF Sheet: Initial (I) Revised (R) Final (F)Document2 pagesIRF Sheet: Initial (I) Revised (R) Final (F)Mark ContrerasNo ratings yet

- Learner Centered TeachingDocument2 pagesLearner Centered TeachingMark ContrerasNo ratings yet

- Corporate Communication Plan - ProjectDocument5 pagesCorporate Communication Plan - ProjectMark ContrerasNo ratings yet

- Work Plan TemplateDocument1 pageWork Plan TemplateMark ContrerasNo ratings yet

- Relevant Sources For Business Ethics & ProfessionalismDocument1 pageRelevant Sources For Business Ethics & ProfessionalismMark ContrerasNo ratings yet

- Composition Grading Rubric: 5 Exceeding StandardsDocument1 pageComposition Grading Rubric: 5 Exceeding StandardsMark ContrerasNo ratings yet

- What Should Then Be Done and THE TRAVELLER - IIS - Allama IqbalDocument35 pagesWhat Should Then Be Done and THE TRAVELLER - IIS - Allama IqbalInternational Iqbal Society100% (1)

- QAI Ruwad Event SummaryDocument3 pagesQAI Ruwad Event SummaryQatar-America InstituteNo ratings yet

- The Woman Who Came AliveDocument5 pagesThe Woman Who Came AliveNowe ChapichapNo ratings yet

- Philadelphia Reads Website Version2Document1 pagePhiladelphia Reads Website Version2api-396310089No ratings yet

- Of Capsicum Spp. Using Different Explants: in Vitro Plant Regeneration in Six CultivarsDocument5 pagesOf Capsicum Spp. Using Different Explants: in Vitro Plant Regeneration in Six CultivarsAriana ChimiNo ratings yet

- NY Nonprofits That Have Had Their Status Revoked by The IRSDocument615 pagesNY Nonprofits That Have Had Their Status Revoked by The IRSSaratogianNewsroomNo ratings yet

- Sons of The Dragon: Demidragon: An Alternative Dragonmage Class, by Ginés Ladrón de GuevaraDocument4 pagesSons of The Dragon: Demidragon: An Alternative Dragonmage Class, by Ginés Ladrón de GuevaraFrodoNo ratings yet

- James Axtell - Columbian Encounters 92-05Document49 pagesJames Axtell - Columbian Encounters 92-05madmarxNo ratings yet

- ResultDocument25 pagesResultRomani BoraNo ratings yet

- Introduction To CultureDocument11 pagesIntroduction To CultureJerald Pastor CejasNo ratings yet

- 2019S Motown Course Outline 4 Rev1Document2 pages2019S Motown Course Outline 4 Rev1fourmackNo ratings yet

- "Consumer Behaviour For Apparels Among Youth ": Lala Lajpat Rai Institute of ManagementDocument50 pages"Consumer Behaviour For Apparels Among Youth ": Lala Lajpat Rai Institute of ManagementSimran KohliNo ratings yet

- The Semiotics of FoodDocument2 pagesThe Semiotics of FoodSurin KaurNo ratings yet

- Pure Culture TechniqueDocument6 pagesPure Culture Techniquebetu8137No ratings yet

- What Makes A Good Change AgentDocument3 pagesWhat Makes A Good Change AgentfaranawNo ratings yet

- Historical Article PDFDocument3 pagesHistorical Article PDFAngela C. AllenNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 - Defining Pop CultureDocument5 pagesChapter 1 - Defining Pop CultureGreen GeekNo ratings yet

- Balancing Growth and Conservation The Case of CartagenaDocument74 pagesBalancing Growth and Conservation The Case of CartagenaHenry FlorezNo ratings yet

- Detroit Sports Memorabilia Catalog 07092019Document11 pagesDetroit Sports Memorabilia Catalog 07092019Anonymous PcCGoyys0% (1)

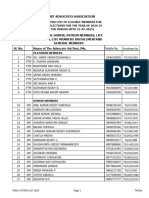

- Final Voter List Thcaa 2024-25Document155 pagesFinal Voter List Thcaa 2024-25Vinod KumarNo ratings yet

- Received Document in M.v.O.P.225 of 2013Document4 pagesReceived Document in M.v.O.P.225 of 2013Vemula Venkata PavankumarNo ratings yet

- China-Lesson Plan Learning Intentions: WWW - Bbc.co - Uk/ni/schools/4 - 11/c Ultureclub/clubhouse/downloads. SHTMLDocument3 pagesChina-Lesson Plan Learning Intentions: WWW - Bbc.co - Uk/ni/schools/4 - 11/c Ultureclub/clubhouse/downloads. SHTMLwolan hariyantoNo ratings yet

- HISTORY of INDIA - Kalachuri Dynasty SanjuDocument10 pagesHISTORY of INDIA - Kalachuri Dynasty SanjuSanjiv GautamNo ratings yet

- EthnocentrismDocument19 pagesEthnocentrismVhim Gutierrez100% (1)

- Harpy: For Other Uses, SeeDocument5 pagesHarpy: For Other Uses, SeeCindy PietersNo ratings yet

- The Beginning of Law and The Adat RechtDocument1 pageThe Beginning of Law and The Adat RechtAisyah KaharNo ratings yet