Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Derivative Markets

Derivative Markets

Uploaded by

Ali Ghafoor0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

35 views39 pagesCopyright

© Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

PPT, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

Download as PPT, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

35 views39 pagesDerivative Markets

Derivative Markets

Uploaded by

Ali GhafoorCopyright:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

Download as PPT, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 39

FINANCIAL MARKETS

In economics, a financial market is a mechanism that

allows people to buy and sell (trade) financial securities

(such as stocks and bonds), commodities (such as

precious metals or agricultural goods), and other

fungible items of value at low transaction costs and at

prices that reflect the efficient-market hypothesis.

Both general markets (where many commodities are

traded) and specialized markets (where only one

commodity is traded) exist. Markets work by placing

many interested buyers and sellers in one "place", thus

making it easier for them to find each other. An economy

which relies primarily on interactions between buyers

and sellers to allocate resources is known as a market

economy in contrast either to a command economy or to

a non-market economy such as a gift economy.

In finance, financial markets facilitate:

• The raising of capital (in the capital markets)

• The transfer of risk (in the derivatives markets)

• International trade (in the currency markets )

– and are used to match those who want capital to those

who have it.

Typically a borrower issues a receipt to the lender

promising to pay back the capital. These receipts are

securities which may be freely bought or sold. In return

for lending money to the borrower, the lender will expect

some compensation in the form of interest or dividends.

Definition

In economics, typically, the term market means the aggregate of

possible buyers and sellers of a certain good or service and the

transactions between them.

The term "market" is sometimes used for what are more strictly

exchanges, organizations that facilitate the trade in financial

securities, e.g., a stock exchange or commodity exchange. This

may be a physical location (like the NYSE) or an electronic system

(like NASDAQ). Much trading of stocks takes place on an exchange;

still, corporate actions (merger, spinoff) are outside an exchange,

while any two companies or people, for whatever reason, may agree

to sell stock from the one to the other without using an exchange.

Trading of currencies and bonds is largely on a bilateral basis,

although some bonds trade on a stock exchange, and people are

building electronic systems for these as well, similar to stock

exchanges.

Financial markets can be domestic or they can be international.

Types of financial markets

The financial markets can be divided into different subtypes:

• Capital markets which consist of:

– Stock markets, which provide financing through the issuance of

shares or common stock, and enable the subsequent trading

thereof.

– Bond markets, which provide financing through the issuance of

bonds, and enable the subsequent trading thereof.

• Commodity markets, which facilitate the trading of commodities.

• Money markets, which provide short term debt financing and

investment.

• Derivatives markets, which provide instruments for the management

of financial risk.

• Futures markets, which provide standardized forward contracts for

trading products at some future date; see also forward market.

• Insurance markets, which facilitate the

redistribution of various risks.

• Foreign exchange markets, which facilitate the

trading of foreign exchange.

The capital markets consist of primary markets

and secondary markets. Newly formed (issued)

securities are bought or sold in primary markets.

Secondary markets allow investors to sell

securities that they hold or buy existing

securities.

The primary market is that part of the capital markets

that deals with the issue of new securities. Companies,

governments or public sector institutions can obtain

funding through the sale of a new stock or bond issue.

This is typically done through a syndicate of securities

dealers. The process of selling new issues to investors is

called underwriting. In the case of a new stock issue, this

sale is an initial public offering (IPO). Dealers earn a

commission that is built into the price of the security

offering, though it can be found in the prospectus.

Primary markets creates long term instruments through

which corporate entities borrow from capital market.

Features of primary markets are:

• This is the market for new long term equity capital. The primary

market is the market where the securities are sold for the first time.

Therefore it is also called the new issue market (NIM).

• In a primary issue, the securities are issued by the company directly

to investors.

• The company receives the money and issues new security

certificates to the investors.

• Primary issues are used by companies for the purpose of setting up

new business or for expanding or modernizing the existing

business.

• The primary market performs the crucial function of facilitating

capital formation in the economy.

• The new issue market does not include certain other sources of new

long term external finance, such as loans from financial institutions.

Borrowers in the new issue market may be raising capital for

converting private capital into public capital; this is known as "going

public."

• The financial assets sold can only be redeemed by the original

holder.

Methods of issuing securities in the primary

market are:

• Initial public offering;

• Rights issue (for existing companies);

• Preferential issue.

• The secondary market, also known as the aftermarket, is the

financial market where previously issued securities and financial

instruments such as stock, bonds, options, and futures are bought

and sold.[1]. The term "secondary market" is also used to refer to the

market for any used goods or assets, or an alternative use for an

existing product or asset where the customer base is the second

market (for example, corn has been traditionally used primarily for

food production and feedstock, but a "second" or "third" market has

developed for use in ethanol production). Another commonly referred

to usage of secondary market term is to refer to loans which are sold

by a mortgage bank to investors such as Fannie Mae and Freddie

Mac.

• With primary issuances of securities or financial instruments, or the

primary market, investors purchase these securities directly from

issuers such as corporations issuing shares in an IPO or private

placement, or directly from the federal government in the case of

treasuries. After the initial issuance, investors can purchase from

other investors in the secondary market.

• The secondary market for a variety of assets can vary

from loans to stocks, from fragmented to centralized, and

from illiquid to very liquid. The major stock exchanges

are the most visible example of liquid secondary markets

- in this case, for stocks of publicly traded companies.

Exchanges such as the New York Stock Exchange,

Nasdaq and the American Stock Exchange provide a

centralized, liquid secondary market for the investors

who own stocks that trade on those exchanges. Most

bonds and structured products trade “over the counter,”

or by phoning the bond desk of one’s broker-dealer.

Loans sometimes trade online using a Loan Exchange.

• Function

• Secondary marketing is vital to an efficient and modern

capital market.[citation needed] In the secondary

market, securities are sold by and transferred from one

investor or speculator to another. It is therefore important

that the secondary market be highly liquid (originally, the

only way to create this liquidity was for investors and

speculators to meet at a fixed place regularly; this is how

stock exchanges originated, see History of the Stock

Exchange). As a general rule, the greater the number of

investors that participate in a given marketplace, and the

greater the centralization of that marketplace, the more

liquid the market.

• Fundamentally, secondary markets mesh the investor's

preference for liquidity (i.e., the investor's desire not to tie

up his or her money for a long period of time, in case the

investor needs it to deal with unforeseen circumstances)

with the capital user's preference to be able to use the

capital for an extended period of time.

• Accurate share price allocates scarce capital more

efficiently when new projects are financed through a new

primary market offering, but accuracy may also matter in

the secondary market because: 1) price accuracy can

reduce the agency costs of management, and make

hostile takeover a less risky proposition and thus move

capital into the hands of better managers, and 2)

accurate share price aids the efficient allocation of debt

finance whether debt offerings or institutional borrowing

Derivative

• A derivative is a financial instrument - or more simply, an

agreement between two people or two parties - that has a value

determined by the price of something else (called the underlying).

• It is a financial contract with a value linked to the expected future

price movements of the asset it is linked to - such as a share or a

currency. There are many kinds of derivatives, with the most notable

being swaps, futures, and options. However, since a derivative can

be placed on any sort of security, the scope of all derivatives

possible is nearly endless. Thus, the real definition of a derivative is

an agreement between two parties that is contingent on a future

outcome of the underlying.

• The spot market or cash market is a public financial market, in

which financial instruments are traded and delivered immediately.

The spot market can be of both types:

• an organized market, an exchange or

• "over the counter", OTC.

• Over-the-counter (OTC) or off-exchange trading is to trade

financial instruments such as stocks, bonds, commodities or

derivatives directly between two parties. It is contrasted with

exchange trading, which occurs via facilities constructed for the

purpose of trading (i.e., exchanges), such as futures exchanges or

stock exchanges.

• OTC-traded stocks

• In the U.S., over-the-counter trading in stock is carried out by market

makers that make markets in OTCBB and Pink Sheets securities

using inter-dealer quotation services such as Pink Quote (operated

by Pink OTC Markets) and the OTC Bulletin Board (OTCBB). OTC

stocks are not usually listed nor traded on any stock exchanges,

though exchange listed stocks can be traded OTC on the third

market. Although stocks quoted on the OTCBB must comply with

U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) reporting

requirements, other OTC stocks, such as those stocks categorized

as Pink Sheets securities, have no reporting requirements.

• OTC contracts

• An over-the-counter contract is a bilateral contract in which two

parties agree on how a particular trade or agreement is to be settled

in the future. It is usually from an investment bank to its clients

directly. Forwards and swaps are prime examples of such contracts.

It is mostly done via the computer or the telephone. For derivatives,

these agreements are usually governed by an International Swaps

and Derivatives Association agreement.

• This segment of the OTC market is occasionally referred to as the

"Fourth Market."

• The NYMEX has created a clearing mechanism for a slate of

commonly traded OTC energy derivatives which allows

counterparties of many bilateral OTC transactions to mutually agree

to transfer the trade to ClearPort, the exchange's clearing house,

thus eliminating credit and performance risk of the initial OTC

transaction counterparts.

Types of derivatives

• OTC and exchange-traded

• In broad terms, there are two distinct groups of derivative

contracts, which are distinguished by the way they are

traded in the market:

• Over-the-counter (OTC) derivatives are contracts that

are traded (and privately negotiated) directly between two

parties, without going through an exchange or other

intermediary. Products such as swaps, forward rate

agreements, and exotic options are almost always traded

in this way. The OTC derivative market is the largest

market for derivatives, and is largely unregulated with

respect to disclosure of information between the parties,

since the OTC market is made up of banks and other

highly sophisticated parties, such as hedge funds.

Reporting of OTC amounts are difficult because trades can

occur in private, without activity being visible on any

exchange.

According to the Bank for International

Settlements, the total outstanding notional

amount is $684 trillion (as of June 2008). Of this

total notional amount, 67% are interest rate

contracts, 8% are credit default swaps (CDS),

9% are foreign exchange contracts, 2% are

commodity contracts, 1% are equity contracts,

and 12% are other. Because OTC derivatives

are not traded on an exchange, there is no

central counter-party. Therefore, they are

subject to counter-party risk, like an ordinary

contract, since each counter-party relies on the

other to perform.

• Exchange-traded derivative contracts (ETD) are those

derivatives instruments that are traded via specialized

derivatives exchanges or other exchanges. A derivatives

exchange is a market where individuals trade

standardized contracts that have been defined by the

exchange. A derivatives exchange acts as an

intermediary to all related transactions, and takes Initial

margin from both sides of the trade to act as a

guarantee. The world's largest derivatives exchanges (by

number of transactions) are the Korea Exchange (which

lists KOSPI Index Futures & Options), Eurex (which lists

a wide range of European products such as interest rate

& index products), and CME Group (made up of the

2007 merger of the Chicago Mercantile Exchange and

the Chicago Board of Trade and the 2008 acquisition of

the New York Mercantile Exchange).

According to BIS, the combined turnover in the world's

derivatives exchanges totaled USD 344 trillion during Q4

2005. Some types of derivative instruments also may

trade on traditional exchanges. For instance, hybrid

instruments such as convertible bonds and/or convertible

preferred may be listed on stock or bond exchanges.

Also, warrants (or "rights") may be listed on equity

exchanges. Performance Rights, Cash xPRTs and

various other instruments that essentially consist of a

complex set of options bundled into a simple package

are routinely listed on equity exchanges. Like other

derivatives, these publicly traded derivatives provide

investors access to risk/reward and volatility

characteristics that, while related to an underlying

commodity, nonetheless are distinctive.

• Common derivative contract types

• There are three major classes of derivatives:

• Futures/Forwards are contracts to buy or sell an asset on or before

a future date at a price specified today. A futures contract differs

from a forward contract in that the futures contract is a standardized

contract written by a clearing house that operates an exchange

where the contract can be bought and sold, whereas a forward

contract is a non-standardized contract written by the parties

themselves.

• Options are contracts that give the owner the right, but not the

obligation, to buy (in the case of a call option) or sell (in the case of

a put option) an asset. The price at which the sale takes place is

known as the strike price, and is specified at the time the parties

enter into the option.

• The option contract also specifies a maturity date. In the case of a

European option, the owner has the right to require the sale to

take place on (but not before) the maturity date; in the case of an

American option, the owner can require the sale to take place at

any time up to the maturity date. If the owner of the contract

exercises this right, the counter-party has the obligation to carry

out the transaction.

• Swaps are contracts to exchange cash (flows) on or before a

specified future date based on the underlying value of

currencies/exchange rates, bonds/interest rates, commodities,

stocks or other assets.

• More complex derivatives can be created by combining the

elements of these basic types. For example, the holder of a

swaption has the right, but not the obligation, to enter into a swap

on or before a specified future date.

FURURES CONTRACTS

• In finance, a futures contract is a standardized contract between

two parties to buy or sell a specified asset of standardized quantity

and quality at a specified future date at a price agreed today (the

futures price). The contracts are traded on a futures exchange.

Futures contracts are not "direct" securities like stocks, bonds, rights

or warrants. They are still securities, however, though they are a

type of derivative contract. The party agreeing to buy the underlying

asset in the future assumes a long position, and the party agreeing

to sell the asset in the future assumes a short position.

• The price is determined by the instantaneous equilibrium between

the forces of supply and demand among competing buy and sell

orders on the exchange at the time of the purchase or sale of the

contract.

• In many cases, the underlying asset to a futures contract may not

be traditional "commodities" at all – that is, for financial futures, the

underlying asset or item can be currencies, securities or financial

instruments and intangible assets or referenced items such as stock

indexes and interest rates.

• The future date is called the delivery date or final settlement date.

The official price of the futures contract at the end of a day's trading

session on the exchange is called the settlement price for that day

of business on the exchange.

• A closely related contract is a forward contract; they differ in certain

respects. Future contracts are very similar to forward contracts,

except they are exchange-traded and defined on standardized

assets. Unlike forwards, futures typically have interim partial

settlements or "true-ups" in margin requirements. For typical

forwards, the net gain or loss accrued over the life of the contract is

realized on the delivery date.

• A futures contract gives the holder the obligation to make or take

delivery under the terms of the contract, whereas an option grants the

buyer the right, but not the obligation, to establish a position previously

held by the seller of the option. In other words, the owner of an options

contract may exercise the contract, but both parties of a "futures

contract" must fulfill the contract on the settlement date. The seller

delivers the underlying asset to the buyer, or, if it is a cash-settled

futures contract, then cash is transferred from the futures trader who

sustained a loss to the one who made a profit. To exit the commitment

prior to the settlement date, the holder of a futures position has to

offset his/her position by either selling a long position or buying back

(covering) a short position, effectively closing out the futures position

and its contract obligations.

• Futures contracts, or simply futures, (but not future or future contract)

are exchange-traded derivatives. The exchange's clearing house acts

as counterparty on all contracts, sets margin requirements, and

crucially also provides a mechanism for settlement.

FORWARD CONTRACRS

• In finance, a forward contract or simply a forward is a non-

standardized contract between two parties to buy or sell an asset at a

specified future time at a price agreed today. This is in contrast to a spot

contract, which is an agreement to buy or sell an asset today. It costs

nothing to enter a forward contract. The party agreeing to buy the

underlying asset in the future assumes a long position, and the party

agreeing to sell the asset in the future assumes a short position. The

price agreed upon is called the delivery price, which is equal to the

forward price at the time the contract is entered into.

• The price of the underlying instrument, in whatever form, is paid before

control of the instrument changes. This is one of the many forms of

buy/sell orders where the time of trade is not the time where the

securities themselves are exchanged.

• The forward price of such a contract is commonly contrasted with the

spot price, which is the price at which the asset changes hands on the

spot date. The difference between the spot and the forward price is the

forward premium or forward discount, generally considered in the form

of a profit, or loss, by the purchasing party.

• Forwards, like other derivative securities, can be used to hedge risk

(typically currency or exchange rate risk), as a means of

speculation, or to allow a party to take advantage of a quality of the

underlying instrument which is time-sensitive.

• A closely related contract is a futures contract; they differ in certain

respects. Forward contracts are very similar to futures contracts,

except they are not exchange traded, or defined on standardized

assets. Forwards also typically have no interim partial settlements or

"true-ups" in margin requirements like futures - such that the parties

do not exchange additional property securing the party at gain and

the entire unrealized gain or loss builds up while the contract is

open. However, being traded OTC, forward contracts specification

can be customized and may include mark-to-market and daily

margining. Hence, a forward contract arrangement might call for the

loss party to pledge collateral or additional collateral to better secure

the party at gain.[clarification needed

• OPTION

• In finance, an option is a derivative financial instrument

that establishes a contract between two parties

concerning the buying or selling of an asset at a

reference price during a specified time frame. During this

time frame, the buyer of the option gains the right, but not

the obligation, to engage in some specific transaction on

the asset, while the seller incurs the obligation to fulfill the

transaction if so requested by the buyer. The price of an

option derives from the value of an underlying asset

(commonly a stock, a bond, a currency or a futures

contract) plus a premium based on the time remaining

until the expiration of the option. Other types of options

exist, and options can in principle be created for any type

of valuable asset.

• An option which conveys the right to buy something is

called a call; an option which conveys the right to sell is

called a put. The price specified at which the underlying

may be traded is called the strike price or exercise price.

The process of activating an option and thereby trading

the underlying at the agreed-upon price is referred to as

exercising it. Most options have an expiration date. If the

option is not exercised by the expiration date, it becomes

void and worthless.

• In return for granting the option, called writing the option,

the originator of the option collects a payment, the

premium, from the buyer. The writer of an option must

make good on delivering (or receiving) the underlying

asset or its cash equivalent, if the option is exercised.

• An option can usually be sold by its

original buyer to another party. Many

options are created in standardized form

and traded on an anonymous options

exchange among the general public, while

other over-the-counter options are

customized to the desires of the buyer on

an ad hoc basis, usually by an investment

bank.

• Types of options

• The primary types of financial options are:

• Exchange traded options (also called "listed options") are

a class of exchange-traded derivatives. Exchange traded

options have standardized contracts, and are settled

through a clearing house with fulfillment guaranteed by the

credit of the exchange. Since the contracts are

standardized, accurate pricing models are often available.

Exchange traded options include:

– stock options,

– commodity options,

– bond options and other interest rate options

– stock market index options or, simply, index options and

– options on futures contracts

• Over-the-counter options (OTC options, also

called "dealer options") are traded between two

private parties, and are not listed on an

exchange. The terms of an OTC option are

unrestricted and may be individually tailored to

meet any business need. In general, at least one

of the counterparties to an OTC option is a well-

capitalized institution. Option types commonly

traded over the counter include:

• interest rate options

• currency cross rate options, and

• options on swaps or swaptions.

• A Foreign exchange derivative is a

financial derivative where the underlying is

a particular currency and/or its exchange

rate. These instruments are used either for

currency speculation and arbitrage or for

hedging foreign exchange risk

Foreign Exchange Risk

• When companies conduct business across borders, they must deal in

foreign currencies . Companies must exchange foreign currencies for

home currencies when dealing with receivables, and vice versa for

payables. This is done at the current exchange rate between the two

countries. Foreign exchange risk is the risk that the exchange rate will

change unfavorably before the currency is exchanged.

Hedge

• A hedge is a type of derivative, or a Financial instrument, that derives

its value from an underlying asset. Hedging is a way for a company to

minimize or eliminate foreign exchange risk. Two common hedges are

forwards and options. A Forward contract will lock in an exchange rate

at which the transaction will occur in the future. An option sets a rate at

which the company may choose to exchange currencies. If the current

exchange rate is more favorable, then the company will not exercise

this option.

Speculation and arbitrage

• Derivatives can be used to acquire risk, rather than to insure or hedge

against risk. Thus, some individuals and institutions will enter into a

derivative contract to speculate on the value of the underlying asset,

betting that the party seeking insurance will be wrong about the future

value of the underlying asset. Speculators will want to be able to buy an

asset in the future at a low price according to a derivative contract when

the future market price is high, or to sell an asset in the future at a high

price according to a derivative contract when the future market price is

low.

• Individuals and institutions may also look for arbitrage opportunities, as

when the current buying price of an asset falls below the price specified

in a futures contract to sell the asset.

• Speculative trading in derivatives gained a great deal of notoriety in

1995 when Nick Leeson, a trader at Barings Bank, made poor and

unauthorized investments in futures contracts. Through a combination of

poor judgment, lack of oversight by the bank's management and by

regulators, and unfortunate events like the Kobe earthquake, Leeson

incurred a $1.3 billion loss that bankrupted the centuries-old institution.

Arbitrage

• In economics and finance, arbitrage is the practice of taking

advantage of a price difference between two or more markets: striking

a combination of matching deals that capitalize upon the imbalance,

the profit being the difference between the market prices. When used

by academics, an arbitrage is a transaction that involves no negative

cash flow at any probabilistic or temporal state and a positive cash flow

in at least one state; in simple terms, it is the possibility of a risk-free

profit at zero cost.

• In principle and in academic use, an arbitrage is risk-free; in common

use, as in statistical arbitrage, it may refer to expected profit, though

losses may occur, and in practice, there are always risks in arbitrage,

some minor (such as fluctuation of prices decreasing profit margins),

some major (such as devaluation of a currency or derivative). In

academic use, an arbitrage involves taking advantage of differences in

price of a single asset or identical cash-flows; in common use, it is also

used to refer to differences between similar assets (relative value or

convergence trades), as in merger arbitrage.

• A person who engages in arbitrage is called an arbitrageur —such as

a bank or brokerage firm. The term is mainly applied to trading in

financial instruments, such as bonds, stocks, derivatives, commodities

and currenci

• Examples

• Suppose that the exchange rates (after taking out the fees for

making the exchange) in London are £5 = $10 = ¥1000 and the

exchange rates in Tokyo are ¥1000 = $12 = £6. Converting ¥1000

to $12 in Tokyo and converting that $12 into ¥1200 in London, for a

profit of ¥200, would be arbitrage. In reality, this "triangle arbitrage"

is so simple that it almost never occurs. But more complicated

foreign exchange arbitrages, such as the spot-forward arbitrage

(see interest rate parity) are much more common.

• One example of arbitrage involves the New York Stock Exchange

and the Chicago Mercantile Exchange. When the price of a stock on

the NYSE and its corresponding futures contract on the CME are

out of sync, one can buy the less expensive one and sell it to the

more expensive market. Because the differences between the

prices are likely to be small (and not to last very long), this can only

be done profitably with computers examining a large number of

prices and automatically exercising a trade when the prices are far

enough out of balance. The activity of other arbitrageurs can make

this risky. Those with the fastest computers and the most expertise

take advantage of series of small differences that would not be

profitable if taken individually.

SPECULATION

• In finance, speculation is a financial action that does not promise

safety of the initial investment along with the return on the principal

sum. Speculation typically involves the lending of money or the

purchase of assets, equity or debt but in a manner that has not been

given thorough analysis or is deemed to have low margin of safety or

a significant risk of the loss of the principal investment. The term,

"speculation," which is formally defined as above in Graham and

Dodd's 1934 text, Security Analysis, contrasts with the term

"investment," which is a financial operation that, upon thorough

analysis, promises safety of principal and a satisfactory return.

• In a financial context, the terms "speculation" and "investment" are

actually quite specific. For instance, although the word "investment" is

typically used, in a general sense, to mean any act of placing money

in a financial vehicle with the intent of producing returns over a period

of time, most ventured money—including funds placed in the world's

stock markets—is actually not investment, but speculation.

• Speculators may rely on an asset appreciating in price due to any of a

number of factors that cannot be well enough understood by the

speculator to make an investment-quality decision. Some such factors

are shifting consumer tastes, fluctuating economic conditions, buyers'

changing perceptions of the worth of a stock security, economic

factors associated with market timing, the factors associated with

solely chart-based analysis, and the many influences over the short-

term movement of securities.

• There are also some financial vehicles that are, by definition,

speculation. For instance, trading commodity futures contracts, such

as for oil and gold, is, by definition, speculation. Short selling is also,

by definition, speculative.

• Financial speculation can involve the buying, holding, selling, and

short-selling of stocks, bonds, commodities, currencies, collectibles,

real estate, derivatives, or any valuable financial instrument to profit

from fluctuations in its price, irrespective of its underlying value.

• In architecture speculation is used to determine works that show a

strong conceptual and strategic focus

Investment vs. speculation

• Identifying speculation can be best done by distinguishing it from

investment. According to Ben Graham in Intelligent Investor, the

prototypical defensive investor is "...one interested chiefly in safety

plus freedom from bother." He admits, however, that "...some

speculation is necessary and unavoidable, for in many common-

stock situations, there are substantial possibilities of both profit and

loss, and the risks therein must be assumed by someone." Many

long-term investors, even those who buy and hold for decades, may

be classified as speculators, excepting only the rare few who are

primarily motivated by income or safety of principal and not

eventually selling at a profit.

• Speculating is the assumption of risk in anticipation of gain but

recognizing a higher than average possibility of loss. The term

speculation implies that a business or investment risk can be

analyzed and measured, and its distinction from the term

Investment is one of degree of risk. It differs from gambling, which is

based on random outcomes. There is nothing in the act of

speculating or investing that suggests holding times, have anything

to do with the difference in the degree of risk separating speculation

from investing.

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5819)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (845)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (348)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Securities Regulation - Cases and Materials - Aspen Casebook SeriesDocument535 pagesSecurities Regulation - Cases and Materials - Aspen Casebook SeriesSimon Holgersen100% (5)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Sample Final Exam Larkin AnswersDocument18 pagesSample Final Exam Larkin AnswersLovejot SinghNo ratings yet

- PD1 - Assignment Brief - Trimester 1Document6 pagesPD1 - Assignment Brief - Trimester 1Fahad MunirNo ratings yet

- Consumer BehaviourDocument1 pageConsumer BehaviourFahad MunirNo ratings yet

- Edition (Sage Publications, 2009) ISBN 1848602162Document2 pagesEdition (Sage Publications, 2009) ISBN 1848602162Fahad MunirNo ratings yet

- Article 223Document1 pageArticle 223Fahad MunirNo ratings yet

- Using Six Sigma in Safety MetricsDocument7 pagesUsing Six Sigma in Safety MetricsFahad MunirNo ratings yet

- Foreign Exchange Markets23984209384Document51 pagesForeign Exchange Markets23984209384Heisnam BidyaNo ratings yet

- Financial Economics 6th Sem Compiled by Aasif-Ur-RahmanDocument45 pagesFinancial Economics 6th Sem Compiled by Aasif-Ur-RahmanKhan HarisNo ratings yet

- By Gary Kamen: Discover The Trading Insight From These Off-The-Radar ResourcesDocument26 pagesBy Gary Kamen: Discover The Trading Insight From These Off-The-Radar ResourcesAdministrator Westgate100% (1)

- PhillipCapital India Corporate Profile 2019Document25 pagesPhillipCapital India Corporate Profile 2019BKSPCNo ratings yet

- CFA Level 1 (Book-B)Document170 pagesCFA Level 1 (Book-B)butabutt100% (1)

- International Swaps and Derivatives Association (ISDA)Document5 pagesInternational Swaps and Derivatives Association (ISDA)Anonymous f5qGAcZYNo ratings yet

- Security AssetsDocument45 pagesSecurity AssetsLalita BarveNo ratings yet

- Option Navigator by Shyam BurmanDocument79 pagesOption Navigator by Shyam BurmanStox WayNo ratings yet

- FMM Curriculum Class Xi and Xii 2008Document52 pagesFMM Curriculum Class Xi and Xii 2008Tanveer VirdiNo ratings yet

- NRB Circulars 2066/67Document26 pagesNRB Circulars 2066/67Pasang LamaNo ratings yet

- Students - Revision Questions Financial Derivatives - 4539222Document2 pagesStudents - Revision Questions Financial Derivatives - 4539222Arpita PatelNo ratings yet

- My Project SharekhanDocument154 pagesMy Project Sharekhankris_sone43% (7)

- 49ae PDFDocument38 pages49ae PDFAleXyya AlexNo ratings yet

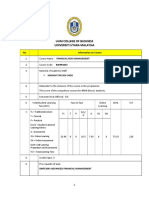

- Uum College of Business Universiti Utara MalaysiaDocument7 pagesUum College of Business Universiti Utara MalaysiaSyai GenjNo ratings yet

- Interest Rate TutorialsDocument81 pagesInterest Rate TutorialsdvobqvpigpwzcfvsgdNo ratings yet

- Futures Trading Guide: August 2014 Editor Matthew CarstensDocument26 pagesFutures Trading Guide: August 2014 Editor Matthew CarstenselisaNo ratings yet

- SyllabusDocument7 pagesSyllabusjiosNo ratings yet

- ArbitrageDocument3 pagesArbitragebhavnesh_muthaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 4 DerivativesDocument38 pagesChapter 4 DerivativesTamrat KindeNo ratings yet

- Hedging Oil Prices: A Case Study On GotlandsbolagetDocument44 pagesHedging Oil Prices: A Case Study On Gotlandsbolagetbumbum12354No ratings yet

- Impact of Basel III On Financial MarketsDocument4 pagesImpact of Basel III On Financial MarketsAnish JoshiNo ratings yet

- SoundPractices Credit Portfolio Management (IACPM)Document61 pagesSoundPractices Credit Portfolio Management (IACPM)poseiNo ratings yet

- 5 - Option and Future DerivativesDocument49 pages5 - Option and Future Derivativesbindu tewatiaNo ratings yet

- Securities (Condon) - 2007-08 (3) - 1Document113 pagesSecurities (Condon) - 2007-08 (3) - 1scottshear1No ratings yet

- Gagan Singh Pal STRDocument63 pagesGagan Singh Pal STRABHISHEK GUPTANo ratings yet

- A Study On Mutual Funds at Indiabulls Securities LimitedDocument67 pagesA Study On Mutual Funds at Indiabulls Securities LimitedKalpana Gunreddy100% (2)

- Chapter-2 Concept of DerivativesDocument50 pagesChapter-2 Concept of Derivativesamrin banuNo ratings yet

- FINMRKT Reflection PaperDocument4 pagesFINMRKT Reflection PaperMaxy BariactoNo ratings yet