Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Acute Renal Failure

Acute Renal Failure

Uploaded by

JoenaCoy ChristineCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Acute Renal Failure

Acute Renal Failure

Uploaded by

JoenaCoy ChristineCopyright:

Available Formats

Acute renal Failure

Renal failure, also called kidney failure, is diagnosed when the kidneys are no longer functioning adequately to maintain normal body processes. This results in dysfunction in almost all other parts of the body as a result of imbalances in fluid, electrolytes, and calcium levels, as well as impaired RBC formation and decreased elimination of waste products. Renal failure can be acute, with sudden onset of symptoms, or chronic, occurring gradually over time. For more information on kidneys, visit the American Kidney Fund at http://www.kidneyfund.org/, the National Kidney Foundation at www.kidney.org, and the American Association of Kidney Patients at www.aakp.org.

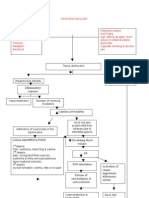

Acute Renal Failure Acute renal failure (ARF) is the sudden (hours to days) loss of the kidneys ability to clear waste products and regulate fluid and electrolyte balance. There is a rapid accumulation of toxic wastes from protein metabolism in the blood (azotemia). In azotemia, the serum urea level (measured by BUN) and creatinine levels are elevated. Most types of acute renal failure are reversible if diagnosed and treated early; however, ARF can lead to chronic renal failure. Acute renal failure is often associated with a urine output of less than 30 mL/hr or 400 mL/day. It may be caused by hypotension, vascular obstruction, glomerular disease, acute tubular necrosis (ATN) in which the tubules are damaged after administration of diagnostic contrast media.

Pathophysiology In acute renal failure, rapid damage to the kidney causes waste products to accumulate in the bloodstream, resulting in the symptoms of renal failure. The patient becomes oliguric, with urine output decreasing to less than 20 mL/h. Treatment is directed toward correcting the cause, supporting the patient with dialysis, and prevention of complications that may lead to permanent damage. Many patients with acute renal failure recover completely. Approximately 50% of patients with intrarenal ARF die as a result of complications of infection, pneumonia, or septicemia. ARF can progress through four stages, with an intrarenal cause taking a longer recovery time frame since there is actual renal damage. Once an event causes ARF in the initial phase, symptoms occur in hours to days.

OLIGURIC PHASE. In the oliguric phase, less than 400 mL of urine in 24 hours is produced. Fifty percent of those with ARF experience this phase, which occurs from 24 hours to 7 days after the initial phase. This phase can last up to 2 weeks to several months. Prognosis for renal recovery is decreased the longer this phase lasts. In the oliguric phase, fluid is retained, electrolytes become imbalanced, and waste products are not excreted as urine output decreases. Signs of fluid overload are seen. Serum potassium rises while sodium is lost in the urine, creating a normal or low serum sodium level. The longer this phase lasts, the more effects are seen. These may include metabolic acidosis from reduced hydrogen ion excretion and sodium bicarbonate levels, increased phosphate and decreased calcium levels, abnormal blood cells (RBC, WBC, platelets), neurological effects ranging from confusion, seizures to coma, and finally effects on all body systems as is seen in CRF (discussed later). DIURETIC PHASE. As the kidneys begin to be able to again excrete waste products, 1 to 3 L/day of urine is produced. The osmotic diuresis occurs from the elevated waste products (urea) which the body is attempting to eliminate. The kidneys are not yet able to concentrate urine and so dehydration and hypotension are a concern. It is important for the nurse to monitor for hypovolemia, hyponatremia, and hypotension in this phase. Serum BUN and creatinine levels are high until the end of this phase, at which time they begin to return to normal. This phase may last from 1 to 3 weeks. RECOVERY PHASE. In this final phase, recovery begins as the glomerular filtration rate rises. Waste product levels (BUN, creatinine levels) decrease greatly within the first 2 weeks of this phase. However, recovery can take up to 1 year. Those who do recover usually do so without complications. Older adults are more at risk for reduced recovery of renal function. In those who do not recover renal function, chronic renal failure occurs.

Etiology

Acute renal failure is often classified as prerenal, intrarenal, or postrenal. These categories relate to the causes leading to acute renal failure. Each category is associated with the location of the cause in the kidney. Understanding the cause can point to the direction of treatment plans helpful to the

patient.

Chronic Renal Failure Chronic renal failure (CRF) affects approximately 290,000 people in the United States. The incidence is on the rise. It is a progressive, irreversible deterioration in renal function where the body is unable to maintain metabolic, fluid, and electrolyte balance. It occurs with a gradual decrease in the function of the kidneys over time. The result is nitrogenous waste products in the blood and uremia. Chronic renal disease affects every body system (Box 37.9 Renal Failure Summary). Etiology

The causes of chronic renal failure are numerous; the most common ones include diabetes mellitus resulting in diabetic nephropathy, chronic high blood pressure causing nephrosclerosis, glomerulonephritis, and autoimmune diseases. Diabetes and hypertension account for close to 70% of all chronic renal disease.

Pathophysiology When a large proportion of the nephrons are damaged or destroyed because of acute or chronic kidney disease, renal failure occurs (Table 37.5). As the nephrons die off, the undamaged ones increase their work capacity and take over the work previously done by the dead ones, so the patient may experience significant kidney damage without showing symptoms of renal failure. Chronic renal failure is a progressive disease process. In the early, or silent, stage (decreased renal reserve), the patient is usually without symptoms, even though up to 50% of nephron function may have been lost. This stage is often not diagnosed. The renal insufficiency stage occurs when the patient has lost 75% of nephron function and some signs of mild renal failure are present. Anemia and the inability to concentrate urine may occur. The BUN and creatinine levels are slightly elevated. These patients are at risk for further damage caused by infection, dehydration, drugs, heart failure, and use of diagnostic x-ray dyes. The goal of care is to prevent further damage, if possible, by control of blood sugar levels and blood pressure. End-stage renal disease (ESRD) occurs when 90% of the nephrons are lost. Patients at this stage experience chronic and persistent abnormal kidney function. The BUN

and creatinine levels are always elevated. These patients may make urine but not filter out the waste products, or urine production may cease. Dialysis or a kidney transplant is required to survive. Uremia (urea in the blood) is present in chronic renal failure. Patients eventually develop problems in all body systems (Table 37.6). If left untreated, the patient with uremia dies, often within weeks.

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5819)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1092)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (845)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (348)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Ao2019 0026Document5 pagesAo2019 0026alissalvqs100% (2)

- UntitledDocument227 pagesUntitledThomas SachyNo ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Burn PathoDocument2 pagesBurn PathoJoenaCoy Christine100% (1)

- HEalth Education Plan CVADocument4 pagesHEalth Education Plan CVAJoenaCoy ChristineNo ratings yet

- Fluid Volume DeficitDocument12 pagesFluid Volume DeficitKersee GailNo ratings yet

- Papanicolaou TestDocument4 pagesPapanicolaou TestJoenaCoy ChristineNo ratings yet

- Placenta Previa Journal KristalDocument23 pagesPlacenta Previa Journal KristalGabbyNo ratings yet

- Breast Cancer ScreeningDocument24 pagesBreast Cancer ScreeningFatih DemirNo ratings yet

- CAV-Chick Anemia VirusDocument21 pagesCAV-Chick Anemia VirusRezaNo ratings yet

- Nle Exam SamplesDocument6 pagesNle Exam SamplesAldrich ArquizaNo ratings yet

- Use of Vasopressors and Inotropes - UpToDateDocument25 pagesUse of Vasopressors and Inotropes - UpToDateVictor Mendoza - MendezNo ratings yet

- MSQH Standard 05 - Prevention and Control of Infection GMDocument30 pagesMSQH Standard 05 - Prevention and Control of Infection GMmiziezuraNo ratings yet

- Pediatric RadiologyDocument82 pagesPediatric Radiologyabakferro0% (1)

- Lecture 9 - Reverse Transcription and IntegrationDocument44 pagesLecture 9 - Reverse Transcription and IntegrationERNEST GABRIEL ADVINCULANo ratings yet

- Drug Study: Adult: ChildDocument4 pagesDrug Study: Adult: ChildKristian Karl Bautista Kiw-isNo ratings yet

- NCP 3 in ER Module (Bernales, JLE)Document3 pagesNCP 3 in ER Module (Bernales, JLE)Jan Lianne BernalesNo ratings yet

- Gallbladder Adenomyomatosis Imaging Findings, Tricks and PitfallsDocument11 pagesGallbladder Adenomyomatosis Imaging Findings, Tricks and PitfallsSamuel WidjajaNo ratings yet

- Paget's Disease: EtiologyDocument8 pagesPaget's Disease: EtiologyMURALINo ratings yet

- Escalas de EfronDocument2 pagesEscalas de Efronkarina100% (1)

- Fetal MonitoringDocument36 pagesFetal MonitoringAshley Etheredge100% (2)

- ASCCP Colposcopy Standards Role of Colposcopy,.3Document7 pagesASCCP Colposcopy Standards Role of Colposcopy,.3Laura Milagros Apóstol A.No ratings yet

- Acute Tonsillopharyngitis - NonexudativeDocument12 pagesAcute Tonsillopharyngitis - NonexudativeLemuel GuevarraNo ratings yet

- Manual Hayat MCQ and OspeDocument19 pagesManual Hayat MCQ and OspeBinte Muhammad100% (1)

- The Stages of Labor AreDocument2 pagesThe Stages of Labor AreSheryll Almira HilarioNo ratings yet

- Post Insertion Problem and Its ManagmentDocument108 pagesPost Insertion Problem and Its Managmentranjeet kumar chaudharyNo ratings yet

- White Blood CellsDocument2 pagesWhite Blood Cellsهاشم ابوطالبNo ratings yet

- Diagnosa GigiDocument3 pagesDiagnosa GigiAntika Fitri LestariyaniNo ratings yet

- 2023 DMI Therapy Referral BrochureDocument2 pages2023 DMI Therapy Referral BrochureBlossoms PhysiotherapyNo ratings yet

- KSMS Quarterly Exam BiologyDocument4 pagesKSMS Quarterly Exam BiologySumitaNo ratings yet

- Pediatric Endocrinology Review Mcqs - Part 2: April 2020Document39 pagesPediatric Endocrinology Review Mcqs - Part 2: April 2020Bhagwani LohanaNo ratings yet

- Removable Prosthodontics: Louis Blatterfein S. Howard PayneDocument6 pagesRemovable Prosthodontics: Louis Blatterfein S. Howard PayneArjun NarangNo ratings yet

- Care of Patient With Musculoskeletal DisordersDocument3 pagesCare of Patient With Musculoskeletal DisordersBryan Mae H. DegorioNo ratings yet

- GONORRHEADocument15 pagesGONORRHEAVer Garcera TalosigNo ratings yet

- 1Document4 pages1Surendra SainiNo ratings yet