Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Green Jakarta: A Cleaner Future?

Green Jakarta: A Cleaner Future?

Uploaded by

PutriKinasihOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Green Jakarta: A Cleaner Future?

Green Jakarta: A Cleaner Future?

Uploaded by

PutriKinasihCopyright:

Available Formats

Monday, June 21, 2010 www.thejakartaglobe.

com/greenjakarta

Green Jakarta

Special Issue Environmental concerns that are shaping the citys development

A Cleaner Future?

Charting the capitals path to sustainability

Green Jakarta

Monday, June 21, 2010 Jakarta Globe

Green Jakarta

Introduction A Difficult Path

ts not easy being green. And its not cheap, either. Separating paper and plastic trash, switching off the light as you leave a room or walking instead of taking a car are simple individual acts that cumulatively can have a great impact. But what about dealing with multimillion-dollar budgets for citywide trash disposal? Or cleaning our skies of deadly smog, providing clean and safe drinking water, and limiting pollution from buildings? Jakarta Governor Fauzi Bowo, a prime target of residents anger about the environmental unfriendliness of the city, knows how tough it is to get things done. On any given issue, he is in the hot seat and facing numerous roadblocks from his constituents, the national government and commercial interests. He doesnt have time to worry about trash clogging a gutter somewhere when any decision to replace the citys landfill in Bekasi with a clean, high-tech incinerator could lead to social unrest. Consider landfill. We pay a tipping fee, Fauzi told the Jakarta Globe in an interview for this special section. For each ton of solid waste, we pay Rp 103,000 [$11] per ton [to a private operator]. Any proposal exceeding that price the city cannot afford. In other words, more eco-friendly trash-handling solutions than traditional landfill technology run up against fiscal realities. If we want to go high-tech, how much do we have to pay for each and every ton of our solid waste? Around Rp 375,000. Where do I get the money? Fauzi asked. Id have to charge more to the people, but who can afford it? So green trash disposal, like a lot of other environmental issues for our messy, sprawling city, are a bit more complex than just tossing a biodegradable bag in your trash can. We all say we want green buildings, cars and water services. But getting there is tough. Buildings can be made greener and cleaner, hybrid vehicles imported. A central water purification and recycling system could ease pressure on the land and city. These are among the issues that officials at the local and national level must tackle through new policies and greater cooperation. So far, the record is not good and we all live with a legacy of pollution in the age of global warming. But that doesnt mean that the citys nine million people are helpless. Jakartas trash recycling industry, for example, is a grassroots creation, built primarily by lowerincome residents. It has now spread to around one-third of the citys 2,500 neighborhood wards. Top-down action alone wont work. Going green is a combination of government policies, local activism and individual action. All three are already happening in Jakarta, but many green issues have yet to be tackled. This special section takes a look at what Jakarta is, or should be, doing to become a greener city, and some of the people who are working behind the scenes to make things better.

35%

of Jakarta was green space in 1965. Now its 9%

9m 30% 35m

now living in a city built for 1 million

Green Space

Great Idea. How Do We Get Some?

Jakarta has lost swathes of undeveloped land over the years, but there are plans to claw some back

Report Annie Dang

city planners target for green space in future expected to live or work in Jakarta by 2020

people a year move to the city

250,000

of the city is occupied by buildings

67%

building licenses issued a year

12,000

CONTENTS

Green Space

Opening the city ....... 3

Green Buildings Green Water

Saving energy ............5 Clean for all ...................8

Green Wheels

Why no hybrids? ......10 Emissions tests ......... 12

Green Garbage

Where can it go? ......13 Scavenger city .........14

airly or unfairly, Jakarta is defined by its neighborhood slums, megashopping malls and torturous traffic. Little attention is paid to its parks - yes, it has some - or the slowly increasing number of outdoor oases that dot the capital, enabling city dwellers to feel, albeit temporarily, as if they're in a verdant land. Despite being congested, a magnet for traffic jams and a case study in urban sprawl, Jakarta could be a more pleasant place in the coming decades. The city is promised a green face-lift as part of a 2010-2030 spatial master plan that will see the development of more green area, although just how much is far from clear. Open space has long been an issue in Jakarta, with environmental and urban-development experts pointing out the obvious: The lack of green makes the city less livable. "There aren't many city parks or neighborhood parks for families to use for enjoyment and recreation. There are plenty of malls and office buildings, but very few outdoor areas for people to enjoy," said Suryono Herlambang, a spatialplanning expert who heads the Department of Urban Planning and Real Estate at Tarumanagara University in Jakarta. The push for a greener Jakarta dates back to the rule of President Sukarno. In 1965, more than 35 percent of Jakarta was green space, but this has been in continual decline ever since due to rapid urbanization and population growth. While Indonesia's founding leader was fond of grand monuments and statues, the national and city leaders who followed didn't

A spatial planning gallery opened this year in Jl. Abdul Muis, Central Jakarta, gives glimpses of planners visions, including this scale model. JG Photo/ Ulma Haryanto

see open space as a priority. And modern Jakarta's history of urban development - numerous master plans and near-zero implementation - saw potential green areas swallowed up by residential and office developments. Today, only 9.3 percent of the city's 661,000 square kilometers is classified as green space. That converts to 65 square kilometers, but it's not as big as it sounds: "green space" is defined as both public and private land, meaning household gardens and potted plants in addition to city and neighborhood parks. "Jakarta has a very limited amount of green area, given the fact that it is overcrowded. There isn't much room to build new green spaces, so we need to look at new ways to develop the ones we already have," Suryono said. "It is not unusual for an overpopulated city like Jakarta to have issues with space, especially green space." The Jakarta administration says it is working overtime to reclaim natural spaces, including by tearing down 32 gas stations that were allowed to sprout in green-belt areas and snapping up plots of land in

about a third of the city's 2,500 neighborhood wards and setting them aside as pocket parks. "If you want to increase the green areas by 1 percent overall, you have to add 5.6 or 5.7 square kilometers of open space. That is five and a half times the size of Monas," Governor Fauzi Bowo told the Jakarta Globe. "Where do you get it in Jakarta? It is a mission impossible." The lack of space has contributed to the mall culture that increasingly defines Jakartans' lives. On weekends, and for some during the week, the city's shopping centers are

They did have plans. They just never implemented them

Historian Andy Alexander on the city planners in the first decades after independence

flooded by families, teenagers and anyone else looking for something to do in a cool, clean environment. While convenient, it's not necessarily healthy - or affordable. Some of Jakarta's more notable green areas are Monas, Taman Suropati, Gelora Bung Karno, Lap Banteng, Ragunan Zoo, Taman Mini Indonesia, Cibubur and a few neighborhood parks in Menteng, Tebet and Srengseng. But Suryono says more green spaces can be developed if the Jakarta administration and the public are a little more innovative. Urban parks can be built along the water-reservoir areas of Pluit, Sunter, Pulomas, Grogol and Tanjung Duren; green spaces can emerge around riverbanks and football fields. "I would also like to see more neighborhood parks. They are great for children and families to play and do activities outdoors," Suryono said. Any chance of turning back the clock, experts say, lies with the 2007 Spatial Planning Law. City planners are now drafting its local regulations, which are aimed at modernizing Jakarta's landscape over the next two decades. Under the

2010-30 master plan, the city is targeting increasing open green spaces from 9.3 percent to 30 percent of the city's area to balance new urban development. Suryono says the 30 percent target is completely unrealistic because Jakarta is already overcrowded and the amount of preserved green space will depend on the commitment of the city administration. The only solution is starting over in a number of areas, he says. "Jakarta is an already overpopulated and overcrowded city, and living space is limited, so building a central green space is not a real option," he said. "There is no area big enough in Jakarta to build a central green area, but by restructuring' certain areas we can create integrated green zones to improve the amount of green space available to the public." Yayat Supriatna, a spatial planner at Trisakti University in West Jakarta, also says increasing green spaces to 30 percent of the city by 2030 is a pipe dream given Jakarta's high population density, which Continued on Page 4

Green Jakarta

Jakarta Globe Monday, June 21, 2010

Monday, June 21, 2010 Jakarta Globe

Green Jakarta

Green Buildings

Rethinking Where We Work and Live

More than a trend, eco-friendly structures can lower emissions

Report Fidelis E Satriastanti

While more parks and playing fields are part of planners promises for the future, construction continues apace across a city where 90 percent of the land is already built up. JG Photo/ Afriadi Hikmal

From Page 3 grows by the year. He says urban planning requires considerable foresight and consideration of such factors as population growth, density and movement. The problem with urban planning and development in Jakarta is the amount of people living in the city, Yayat said. Jakarta is handicapped in that respect because there is limited living space and continual urban sprawl. This affects the quality of spatial planning, with more and more people moving to the city. Each year, more than 250,000 people move to Jakarta for education and work opportunities. The uncontrolled movement of people puts tremendous pressure on the city's infrastructure and increases the demand for housing, which runs counter to the plan to create more green space. According to Rachmat Witoelar, a former state minister for the environment, Jakarta was designed to support a population of about a million, but it's now nine times that number. A recent study by the Economy and Environment Program for Southeast Asia named Jakarta as the most vulnerable city in the region to the impacts of climate change

because of its high population density. After the release of the study, Witoelar called for new regulations to stem the tide of migrants coming into the capital each year, saying population density had become an urban-development issue in addition to one of public health. As part of its goal to increase green space, the Jakarta administration has proposed clearing out illegal squatter communities along rivers and railway tracks and converting the land into parks, gardens and playgrounds. This is easier said than done, of course, for many complex reasons, and activists are already complaining that the communities have not been consulted. The city itself is also in a bind. It is notoriously difficult to acquire land for any public project, and clearing away squatters for green spaces is certain to result in a tangle of court cases and messy publicity. The last thing any Jakarta governor wants to see is a pitched battle between public-order officers and local residents over the demolition of a community. It is just such a nightmare of conflicting claims that resulted in the April rioting that left three dead in Tanjung Priok when officials attempted to clear land designated to be part of an expanded port.

The problem with urban planning and development in Jakarta is the amount of people living in the city. There is limited living space and continual urban sprawl.

Yayat Supriatna, spatial planner at Trisakti University

Ubaidillah, a member of the Indonesian Forum for the Environment (Wahli), says the city's spatial master plan is badly flawed in its current form. "It is not clear how the government plans to go about fulfilling its objectives," he said. "Furthermore, it did not really consult with the community in developing this plan or seek what the communities really want and need." Jakarta-based nongovernmental organizations also have questioned what will happen to squatters once they are removed. The city has considered relocating them to government-built low-cost housing complexes, but there's resistance among slum dwellers to move too far from their current homes. It also remains to be seen who would fund the new complexes. "Slum neighborhoods are built in certain areas because those areas are in close proximity to the source of their income," Suryono said. "It's not fair that people live in an area that floods every year, but it's also not fair if they are removed." While the city's plan has stirred debate among environmental groups about the ethics of removing people to open up more green space, it's not even certain that it will go forward. "The details of the plan itself are uncertain," Ubaidillah said. "We

don't know what the plan is, where the new green spaces will be or who will be affected. This makes it hard for us to react, comment and campaign for a better proposal." Much of the negative reaction stems from the lack of certainty surrounding the city's draft bylaw, which has been under development for the past year. "It's not clear what strategy the government is taking to achieve more green space and what these green spaces will actually be used for," Suryono said. "And if the government does build new green spaces, where will these areas be and what will happen to the offices or homes in these areas?" Ubaidillah argues that the Jakarta administration should be looking to develop other options to create more green space. "The government should not only be looking to move people and clear already occupied spaces to create more green spaces in Jakarta," he said. "It should also look at buildings and areas breaking environmental rules and pull them in line to meet the green standards and quality expected of a green city." Green spaces. Everyone loves the concept. But retrofitting this messy city to make it happen seems certain to be one of the largest single challenges ahead.

oing green is far more than just a catchy slogan. Recycling waste, reducing plastic use and planting trees are just the best-known actions people take to help the environment. Less frequently considered, however, is the green building likely because there are common misconceptions about the concept. Actually, the idea of a basic green building has just three guiding principles: low cost, low technology and high impact. So, if you think a green building, condo or house is about a lavish lifestyle using flashy technology, think again. A green building is plain and simple. You dont have to use specific brands, just change your lifestyle and how you use technology and materials. The keyword is efficiency, said Nirwono Yoga, chairman of the Indonesian Landscape Architectural Study Group. Nirwono, a spatial planning expert from Trisakti University in West Jakarta, says the idea is to conserve water and electricity because of ever-increasing demand in big cities such as Jakarta, while lowering carbon emissions. Trying to build a more ecofriendly building is nothing new. The idea has been steadily growing since the 1950s when scientists first began converting solar energy, albeit at a low level, into electricity. In the 1970s, green building was a common call in the environmental movement, spawned by energy crises and skyrocketing fuel prices in the United States and other Western nations. Back-to-the-earth activists in the United States at the time sparked a low-level boom in adobe housing, rooftop gardening and other natural approaches to dwellings. But the idea that big buildings should be more energy-efficient lay largely dormant until former US Vice President Al Gore became the poster boy in recent years for growing concern about global warming. Now it seems that everything has to be

green, including buildings. Green building is not a new thing, however, sometimes its popular and sometimes its eclipsed by some other trend, Nirwono said. Green building needs to be a lifestyle, not just a trend. If its only a trend, the next question would be: How long can this last? For his part, Jakarta Governor Fauzi Bowo must hope that green is here to stay. Inheriting a capital city with a laundry list of problems, including with water and electricity supply, the governor embraced the green building idea in 2008. He has publicly announced his intention to make the citys buildings greener beginning this year by issuing a special decree. What are green buildings? he asked rhetorically during an interview with the Jakarta Globe at his office. The answer, he says, are buildings that are energy-efficient, recycle their water and have fewer emissions. New buildings will have

to comply with the forthcoming decree, Fauzi says, while older buildings that are renovated must be retrofitted with green technology. The Jakarta administration will provide financial incentives for both new and old buildings that go green. Im starting with my own building next door, he said, referring to City Hall, located next to his office. This is going to set an example for every building in Jakarta. Starting next year, we are going to continue with all school buildings that are owned by the government. Nirwono says Jakarta has no choice but to start making its government offices, commercial buildings and shopping centers more environmentally friendly, given chronic power problems and water shortages. It should be done immediately in Jakarta, because we are talking about energy efficiency. We have an energy crisis here with blackouts everywhere. It is just a matter of time before we really run out of electricity, he said. In addition, we also are dealing with a scarcity of clean water. Who can guarantee that in the next 20 years, the city can still provide enough water for all of us? By 2020, 35 million people are expected to be living in Greater

Just change your lifestyle and how you use technology and materials. The keyword is efficiency.

Nirwono Yoga, chairman of the Indonesian Landscape Architectural Study Group

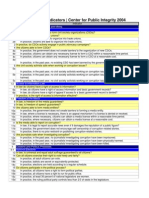

Chill New Idea | How to keep concrete cool in hot climates

Indonesian cement company Holcim says it plans to test a system of cooling pipes embedded in concrete to save energy

Used air outflow

Water cooled concrete slap (21-23 degrees) controls room temperature based on the principles of radiation cooling Insulation facade and low-E double windows with outside sun protection

Radiation cooling Air rises at 30cm per second, warming people and appliances

2.7 m

Dry and cooled air array

Fresh and dried air inflow (23-26 degrees) with low speed and 1-2 air exchanges per hour

Jakarta, nearly doubling the demand for water and electricity. PT Holcim Indonesia, the local unit of the international cement giant, is pushing the idea of sustainable buildings meaning they must meet economic targets for saving energy and water. It means that if a green building is not economical, then it will not sell, said Alex Buechi, manager for sustainable construction at Holcim Indonesia. Conserving water and using less power are noble goals, but the most immediate impact from green buildings, whether they be high-rise office towers, apartments or houses, will be to the owners bank accounts. People just take these matters for granted and never see them as benefits. If you can save Rp 250,000 per month on electricity, over 20 years thats a huge savings, Nirwono said. Thats one benefit from saving electricity, not to mention saving water. He says most people never consider saving money on a monthly power or water bill as a long-term investment, noting construction costs for a green building are usually only 10 percent more, while renovating an existing building into a green one is only half the price of building a new one. The savings over the life of a building on energy and water costs, Nirwono says, can be substantial and more than offset any construction premium. Naning Adiwoso, chairwoman of the Green Building Council of Indonesia, also debunks the myth that pricey technology is at the heart of going green. Yes, we need technology, but it does not necessarily mean [advanced] technology. Most of it is actually available on the market, such as energy-saving lamps, eco-washers and even eco-toilets, Naning said. We dont need complicated technology, because usually it just goes back to how to install windows and doors to get enough light or air, so you dont need to turn on the lights during the day. She says the real challenge in promoting green buildings is changing the mind-set that it will cost more. But Nirwono says that when pricier technology is needed, the expense is worth it. These items should be considered as long-term investments, for instance, LED lamps. They are a new technology Continued on Page 6

SOURCE: PROF BRUNO KELLER HOLCIM

Green Jakarta

Jakarta Globe Monday, June 21, 2010

Monday, June 21, 2010 Jakarta Globe

Green Jakarta

The Nuts and Bolts of Setting Green Building Standards

While green buildings houses, skyscrapers, shopping centers are touted as a win-win solution for developers and the environment, both saving money and preserving power and water, its not as easy as it sounds. Just ask the Jakarta administration, which since last year has been trying to come up with a better formula to regulate and set standards for green buildings. This is one of the most complicated regulations ever, because we need to measure carefully all the consequences once this regulation takes effect, said Pandita, head of planning and structure implementation at the Jakarta Building and Monitoring Agency (P2B). We are still struggling with lots of things, starting from whether the regulation should be applied to all kinds of buildings, whether there will be incentives or disincentives. Above all, he said, the regulation, which should be completed this year, must not be a burden for city dwellers. Last year, the administration launched a pilot project to renovate Blok G of City Hall, which should be finished this year, and will construct a new provincial legislature building in Central Jakarta, also this year. Initially, the green-building regulation will target city government offices, as well new building licenses, Pandita said. It is a lot easier to do it on new buildings than on existing ones, as theyll just need to comply with environmentally friendly requirements. If they pass, then we will be able to issue the permit. He said the Jakarta Building and Monitoring Agency usually issued 10,000 to 12,000 new licenses a year, mostly for residential housing.

From Page 5 that is considerably more expensive, but it will pay off after 10 years, he said. It can work if people dont treat it as just another trend or a source of pride for using green materials. Sithowati Sandrarini, a 42-yearold economist, says the only major spending she did for the ecoconscious renovation of her house in South Jakarta was on the structure. I only paid a lot up front for the early construction because it needed to be solid, but none of my [interior] items were expensive, she said. All of my furniture is from recycled wood, the doors are from old wood, the plant pots are old milk cans. There are no expensive treatments whatsoever and the plants are here to filter the air. In 2005, Sithowati met architect Adi Purnomo, who shared the dream of seeing more eco-friendly houses in Jakarta and began renovating her house. I didnt understand the whole green building [concept] at the start, but I did want a house that was environmentally friendly, especially one that could save lots of

What Makes a Building Green?

A green building, also known as a sustainable building, is a structure designed, built, renovated, operated or reused in an ecological and resource-efficient manner. Green buildings are designed to meet certain objectives such as protecting occupant health, improving employee productivity, using energy, water and other resources

While the Jakarta administration will draft and enforce the greenbuilding regulations, the Green Building Council of Indonesia, a Jakarta-based nonprofit organization, will be tasked with issuing green-building certification. The council was established in 2008 by 50 architecture and interior-design professionals to promote environmentally friendly homes and other buildings in the country. Bintang A Nugroho, director of public affairs at the council, said the certification, known as Greenship, was voluntary and would include higher standards than the coming city regulation. There are five requirements for certification as a green building: smart land use, conserving energy and water, saving materials, reducing toxic chemicals and creating better air quality. This is not to be confused with the governments licensing, which will be mandatory. We are dealing with the status of the building, Bintang said, adding that the council also wants to establish a market for green-building materials. Suzy Hutomo, chief executive officer of Body Shop Indonesia, said her company was conducting an audit so it could reduce energy use at its stores. She said the greenbuilding regulations would need to have an educational component. Certainly, regulations will help if it they are well enforced, but I think that it will be an uphill battle, Suzy said. If it is not accompanied by education, it will lead to more corruption to get around the standards, as it costs about 10 or 15 percent more to construct [green buildings]. Fidelis E Satriastanti

energy and was bright, while still using sound architectural principles, Sithowati said. Not only did she get the house of her dreams, but her home was named Best Residence by the Indonesian Institute of Architects in 2005. Its now a shining example of what can be done to make a residential structure green. The reasons for making our buildings green dont stop with interior decorating or power bills. Green buildings can also reduce global emissions dramatically. A 2007 report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, the body tasked with evaluating the risk of climate change, estimated that building-related greenhouse gases account for about 40 percent of the worlds total emissions, and will almost double by 2030 to 15.6 billion tons of CO2 . This is especially true in congested urban centers like New York and London, where vehicle emissions have gone down but building emissions remain high. Our understanding is that transportation and industry are the biggest contributors [of greenhouse

more efficiently, and reducing the overall impact on the environment. A green building may cost more up front, but saves through lower operating costs over the life of the building. The green building approach applies a project life cycle cost analysis for determining the appropriate up-front expenditure. This analytical method calculates costs over the useful life of the asset. These and other cost savings can only be fully realized if incorporated at the projects conceptual design phase with the assistance of an

integrated team of professionals. The integrated systems approach ensures that the building is designed as one system rather than a collection of stand-alone systems. Some benefits, such as improving health, comfort, productivity and waste management are not easily quantified. Consequently, they are not adequately considered in most cost analyses. For this reason, developers are urged to set aside a small portion of the building budget to cover differential costs

associated with less tangible green building benefits or to cover the cost of researching and analyzing green building options. Even with a tight budget, many green building measures can be incorporated with minimal or zero increased up-front costs and they can yield enormous savings. Some green building practices: Select a site close to mass transit; Protect and retain existing landscaping and natural features; Select plants that have low water

and pesticide needs; Use recycled paving materials, furnishings and mulches; Use passive design strategies to enhance energy performance; Provide natural lighting. It has a positive impact on productivity and well-being; Install high-efficiency lighting systems with advanced controls; Use an energy-efficient cooling system alongside a thermally efficient building shell. Tips from California Department of Resources Recycling and Recovery

Green Hero The Neighborhood Planter

Garbage Warrior Empowers the People

Sithowati Sandrarini's eco-home in South Jakarta has become a shining example of how to build using recycled and cheap but energy-efficient materials. It won a Best Residence award from the Indonesian Institute of Architects in 2005. JG Photos/ Afriadi Hikmal

arini Bambangs eyes light up as she recounts some key phases of a life spanning nearly eight decades. There was growing up in the 1930s in Solo, volunteering as a nurse during Indonesias war of independence in the late 1940s, and then, her most important battle of all: her fight for a greener country. I call myself the garbage warrior, she says, laughing, because thats what I do. I fight the waste management battle by talking about issues of waste and educating people how to help reduce their garbage. As a young girl, Harini never dreamed of being an environmental pioneer, advocate or educator. National and international recognition were certainly never an objective either. All she wanted was for her house and neighborhood in Banjarsari, Jakarta, to be as beautiful and green as Solo. My father was a farmer, so I learned a lot about plantations, agriculture and farming, she says. He taught me how to cultivate plants and sow. Thats how gardening became my hobby. The idea to create a green neighborhood mostly came from my childhood memories of my hometown. I wanted my neighborhood in Jakarta to look just like that. Everything else, she says, grew from there. I started by gardening and greening my home, and then I encouraged my neighbors to plant flowers at their homes, she says. It was only later that I started campaigning for a greener neighborhood. Harini, 78, moved to Banjarsari in 1980. At that time it was not the diverse suburban landscape it is today it was a rubber plantation. With the help of her late husband, Bambang Wahono,

Better waste practices start in the home before happening in the community or the world

Harini Bambang

who was then the head of the neighborhood unit, she began raising awareness about the importance of greening and waste management. In the beginning, campaigning for a greener neighborhood was not easy. There were many challenges, she says. The biggest challenge was pro and contra people; those who opposed what I did and those who supported what I did. But because I have a strong will, I just kept going. Without it I would have given up long ago. Even today, as a nationally recognized waste management trainer and go-to source for the media on green issues, Harini

I wanted a house that could save lots of energy, while still using sound architectural principles

Sithowati Sandrarini, green homeowner (right)

gasses], causing global warming, but instead, the real culprit is actually buildings, Nirwono said. It also means that making buildings more environmentally friendly will have a positive effect on reducing emissions and global warming. One example is Council House 2 in Melbourne, Australia, a cityowned office complex that opened in 2006 and is considered a showpiece of urban design that conserves water and electricity. CO2, as it is known, has become a model for such efforts worldwide. Buildings contribute CO2 emissions starting from the [beginning of construction] and also the materials, Nirwono said. For instance, if you want Italian ceramic tiles for the floor, you need airplanes

to fly them in and airplanes use fossil fuel. They leave carbon footprints everywhere. Finished buildings emit CO2 from giant air-conditioning units that spew heat into the air. In Jakarta, Holcim Indonesia is promoting a European-derived cooling technology that can keep concrete in warm climates radiating at 23 degrees Celsius. Buechi says the technology can reduce the energy required to cool buildings and homes by 75 percent, and is used worldwide, including in Egypt, India and China. Wed be saving one additional power plant if it was widely used here, Buechi said. Holcim plans to install the cooling system in a building in Pondok Indah.

There are also calls for new buildings to have more mandatory green space to help absorb carbon emissions. Nirwono notes that Jakartas green areas comprise only 9.3 percent of the city, while buildings take up 67 percent. Dont use up all your land area for a building or house, allocate some to make a park that would function as a carbon absorber, he said. To cool her house and create a personal park, Sithowati planted grass and vegetation on her roof and balcony. I did some studying and found that putting up soil and grass could reduce the temperature by 1 degree, which is why my house is still very cool, even during the day. And at night, it can be chilly, she said.

Some of the fruits of Harini Bambangs labor. Her home garden and enthusiasm soon inspired her Banjarsari neighbors. JG Photo/Annie Dang

says there are still people out there who might question her abilities. Some people involved in similar environmental work question why she gets so much attention and recognition. Harini says people dont exactly object, but they question why journalists seek her out, and why she is selected to travel to speak on waste management issues. While it may be hard for a warm soul like Harini to understand why people feel this way, the answer is a long list of achievements. She has conducted more than 60 environmental workshops in various districts throughout Sumatra, Java and even Kalimantan, and is regularly invited to give speeches on regional environmental issues in the Philippines and Thailand. In 1996, Harini was named Unescos instructor for a pilot community waste management project. The reduce, reuse, recycle and replant campaign has since been adopted and implemented in 25 neighborhoods across the country. Her tireless campaigning has not only earned her a spot on environmental posters and bookmarks, but also the 2001 Kalpataru environmental award, which Harini says was a highlight of her work. Despite all the ups and down, Harini remains unaffected by the attention, hype and even controversy that surrounds her. I find that if I work with my heart and there is love in my heart, I can achieve anything, no matter how hard the task may be, she says. For Harini, a major of source of this love comes from the support and care of her family. Her third son, Bambang Irwan, works with her on her campaigns and programs and accompanies her on out-of-town and overseas work trips. The other source of the love Harini feels comes from the affection of strangers. During a World Health Organization conference in Bangkok last year, Harini was approached by a doctor who embraced her and thanked her for being an inspiration. I was very touched by that. It made me cry, especially to see that I could help people from other countries that are not my own, she says. Its important for people to learn that waste can be reused in different ways. Adopting better waste management practices starts in the home before it can happen in the community or in the world. Annie Dang

Green Jakarta

Jakarta Globe Monday, June 21, 2010

Monday, June 21, 2010 Jakarta Globe

Green Jakarta

Green Water

Or Any Color as Long as It Is Clean

Water may be a bigger crisis than global warming, some experts believe

London, its already been through seven stomachs, said Scott Younger, president commissioner of Glendale Partners, a Jakarta-based project development and consulting firm. It might sound sick and disgusting, but recycling wastewater is nonetheless an ingenious way to solve water-supply problems, and more cities around the world are doing the same thing. One day, Indonesian cities like Jakarta, which has its own massive water supply woes, may have no choice but to recycle wastewater even if its just for industrial use or to replenish toilets and showers in office buildings, shopping malls and hotels. In fact, it should already be doing so, according to experts. Water is precious and its the most important [issue] of this century forget climate change, Younger argued, noting that Indonesia only reuses 1 percent of its rainwater. Reusing water was never a priority for Jakarta, but in Singapore and Hong Kong, its part of [public] policy. The Jati Luhur reservoir in West Java is literally Jakartas lifeline, supplying up to 60 percent of the citys water needs, but problems with quality and consistent flow keep water experts up at night. Another 25 percent or so of the citys supply comes from groundwater, but the Jakarta administration has begun to phase that out through prohibitive tariffs to prevent the northern part of the city from sinking and being overrun by high tides. Luckily, there are some officials outside Jakarta who think creatively about water conservation in their communities. Jakarta may want to look to them as it tries to go green with its water. Itoc Tochija, mayor of Cimahi, West Java, has invited foreign and Indonesian scientists, development experts and nongovernmental organizations to his town of 600,000 to share solutions to our problems. Those problems includes clean water shortages during the dry season, and a complete absence of a sewage system in Cimahis slum areas. Tochija didnt shy away from trying something new, approving a pilot project for a machine that turns low-to-medium polluted river water into drinking water. He also approved the experimental use of a sewage tank created by a university in Malang, East Java, that cleans wastewater before releasing it into the Cimahi River. Today, two giant tanks are at work in the towns slum areas. So why isnt Jakarta as proactive? I dont know, Tochija said. I think some parts of Jakarta are very green. But they are rich they should at least have communal septic tanks in [slum areas of] North Jakarta like we do here. Indeed, Jakarta appears to be the only major city in the world without a centralized municipal wastewater treatment plant. On one level, thats just fine for Muhtadi Sjadzali, managing director of Envitech Perkasa, which builds wastewater and water treatment plans for industrial use. The recycled wastewater that emerges from the machines built by the company is of a higher quality than drinking water, and is used to power boilers that create electricity for factories. Envitech Perkasa built a wastewater treatment plant in Surabaya for Unilever, which paid for itself in just three years from the money saved on electricity costs. The driver for recycling in industry, if you talk to them, is that they want zero emissions thats all public relations talk, Sjadzali said. Its really driven by the costs. While his company has no shortage of business, Sjadzali is also a proud Indonesian and Jakarta resident, and says he fears the capital has exceeded its carrying capacity for water. He said the only feasible solutions are to stop new construction, desalinate seawater into potable water and recycle existing sewage water. Every building in Jakarta should recycle their sewage water, but what do you use it for? Sjadzali said, estimating that around half of Jakartas buildings have their own sewage systems but only a fraction of them recycle. Psychologically, people wont accept drinking water from sewage. Fair point, but given that wastewater can be turned into high-quality water, it can easily be reused in toilets, sinks and showers. If the Jakarta administration issued a regulation on mandatory recycling of water within city office buildings, Sjadzali said, ultimately demand could decrease by up to 40 percent. But first you have to clean up the [citys] rivers, he said. Recycling is good, but the focus should be on stopping pollution in river water, so it can be used at least for cleaning and showering.

Green Hero The Hygiene Evangelist

One Mans Journey: Software to Sanitation

Report Joe Cochrane

or the past 10 years, Mahmud has sold bottles of Aqua and soft drinks from his streetside kiosk in Central Jakartas Menteng district. At Rp 2,000 (22 cents) a pop, his profit margin is small, but its a living. But suppose Mahmud had the option of selling a different brand of drinking water that was cheaper for him to buy from distributors, allowing him to increase his profit? Most vendors would jump at the chance. But what if this new beverage was made from recycled sewage water? I dont think people would buy recycled water like that, so I wouldnt sell it, Mahmud, 46, said. I think maybe if they didnt know where the water came from, they would drink it. But once they did, I dont think they would want it. Not necessarily. Naysayers in Singapore said the same thing for decades as the city-states government worked to resolve its chronic water shortages by recycling wastewater for commercial and industrial use. To prove a point about cleanliness, they also began bottling recycled water for human consumption, publicizing the fact that their NEWater product surpasses the World Health Organizations requirements for safe potable water. Today there are five plants in Singapore that produce NEWater, primarily for industrial and commercial uses, and its targeted to meet up to 30 percent of Singapores water needs by this year. And some NEWater is also sold in mini-marts and grocery stores. One survey even showed that 98 percent of Singaporeans have no problem drinking recycled water, and theyre certainly not alone. If you drink from the taps in

Drink up. In Singapore, recycled wastewater is sold in stores.

Recycling is good, but the focus should be on stopping pollution in river water

Muhtadi Sjadzali, managing director of Envitech Perkasa

A tall, cool glass of water with extra swizzle might be great on a hot afternoon, but Jakartans cant take it for granted. Poor re-treatment facilities, lack of a consistent supply and heavy pollution all plague the citys water.

Indonesia is said to reuse only 1 percent of its rainwater.

Experts estimate that around 25 percent to 30 percent of river water that goes into Jakartas treatment plants doesnt meet official health and quality standards for untreated water. And in Cimahi, Mayor Tochijas pilot water purifying machine doesnt work downriver on water that flows past the areas factories because its far too polluted. In the planned community of Lippo Karawaci, on the outskirts of Jakarta, there are no worries about the quality of the water its saves. All drainage is contained and directed to its golf course and water ponds for storage. The reserve keeps the underground aquifer replenished and it comes in handy when theres a drought. All buildings and homes in Karawaci have piped water and are hooked up to a central sewage system, a simple concept with proper planning that must seem alien to Jakarta. Discharged waste is

treated in a central sewage treatment plant, and the cleaned water is diverted back to the six water ponds scattered around the community or used for irrigation. Its been like this for 15 years. This is not rocket science, said Wahyudi Hadinata, general manager of Lippo Karawaci. This concept of a water pond is just something new for the government they cant understand it. To be fair, the present Jakarta administration didnt start with 1,000 hectares of open land like Lippo did in the early 1990s. But city officials shouldnt have any problem understanding that water is an expensive commodity, not to mention the fact that the citywide supply is inconsistent. Wahyudi suggested a regulation mandating that all buildings or at least new buildings treat and reuse sewage water, and collect, treat and use rainwater.

In the long run, it will be cheaper than the commercial water rate, he said, adding that to kick-start the process, the city could raise the water rates. Give them an incentive to change. If most Jakartans think like Sanyoto, a 42-year-old private driver, then the recycled water idea could catch on. I think if it has been processed correctly, I wouldnt mind, he said. I mean, thats what water from the [city water utilities] is; its source comes from the Ciliwung River, which is polluted. But because it has been processed, its clean, so its OK. OK to use and even reuse for commercial buildings and industry, but for drinking? Thats going to take some time. I cant imagine drinking sewage water no way, said Siti, a 17-year-old baby sitter in Jakarta. I cant stand the mental image, even if it is clean.

he field of sanitation, hygiene and health management may not be the worlds sexiest, but as head of a neighborhood unit in North Petojo, Central Jakarta, Irwansyah has made a career out of it. Its a job that the 44-year-old says is as far-removed as possible from his educational background in computer management. I dont know why I decided to work on environmental issues or what inspired me, but I enjoy it, he says. Its a whole different world to computers. But a world no less fulfilling, he points out. Irwansyah has rubbed shoulders with President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono, discussed drainage and sewage with the mayor of Central Jakarta and taken US Sectary of State Hillary Clinton on a tour of North Petojos communal toilet facilities during her visit in February 2009. For Irwansyah, the journey to becoming an environmentalist was more about helping his community than anything else. Helping my neighborhood has always been something I hold onto, an ideal, and it has been a great and rewarding experience to help and educate the people about health, he says. Last year, Irwansyah received the countrys highest acknowledgement for environmental work, the Kalpataru, an award given by the State Ministry for the Environment to people who have dedicated their lives to environmental issues. Receiving the award of course was the highest honor I could receive. It gives me a lot of pride and makes me proud that the government appreciates my work, Irwansyah says. But despite the hype and prominence that goes with receiving such a distinction, Irwansyah says his feet are firmly planted on the ground. Yes, it was an honor, but I am more concerned about

Poor sanitation and hygiene are caused by habits that are passed down

Irwansyah, neighborhood unit head in Central Jakarta

continuing to try to change the behavior of people; changing their behavior from having bad habits to half-good habits, he says. I use the phrase half-good because there are still a lot of issues that need attention and need to be worked on. We still have a lot to improve on sanitation and hygiene. Poor sanitation causes at least 120 million cases of disease and 50,000 premature deaths in the country every year, according to the World Bank. Diarrhea-related diseases are the most common, with 89 million cases nationwide annually, followed by skin disorders and trachoma, a

North Petojos innovative toilet facilities turn feces into usable biogas, cutting down on the waste that enters the river. JG Photos/Annie Dang

contagious bacterial conjunctivitis that can lead to blindness. As a neighborhood head, Irwansyah oversees a number of green activities in North Petojo, a riverside slum of 3,321 people. These include sanitation improvement training projects, the quarterly cleaning of the Krukut River and health programs for pregnant women and children under 5. While the neighborhood has received a number of green awards, it is most recognized for a pilot sanitation system project, which includes special toilet facilities that use buffer reactivity to turn feces into usable biogas. Buffer reactivity technology has been used to reduce the amount of domestic and industrial waste entering the citys waterways and improve overall water quality in Jakartas rivers. By having buffer reactors, we can turn domestic waste from toilets into fuel for the community kitchen and use the chambers within the reactors to treat wastewater for E coli bacteria or other dangerous bugs before it goes into the river, Irwansyah says. This will help to improve sanitation and stop the spread of disease. The concept and technology is not only innovative, it has proven to be a hit with the local community. Irwansyah attributes this to motivating the community to not only get behind the project, but also to participate in building the infrastructure for the system. He says he hopes this model of community motivation will be adopted and applied in other areas of Indonesia and Asia. The important thing is that there needs to be a motivator and the people in the community must be willing to make that change, he says. Poor sanitation and hygiene are caused by habits that are passed down from generation to generation. So unless people are willing to change, it will be hard for us to make them change. This new approach even caught Clintons attention. I got a call from the US Embassy in Jakarta telling me that this big-shot American would be coming, but they didnt say who, he says. I told them it must be Hillary Clinton. The embassy staff were shocked. I told them I saw on Metro TV that she was coming to Indonesia. For his next act, Irwansyah says he hopes North Petojo will play host to US President Barack Obama if and when he makes his oft-delayed state visit to Indonesia. Now that he is used to rubbing shoulders with politicians, Irwansyah will be more than ready to talk sewers and toilets with him. Annie Dang

10

Green Jakarta

Jakarta Globe Monday, June 21, 2010

Monday, June 21, 2010 Jakarta Globe

Green Jakarta

11

Green Wheels

Why Are Cleaner Cars Still Elusive in Jakarta?

Punitive tax rules, poor fuel quality and simple inertia keep Jakartas skies smoggy

countrys infrastructure might not be ready to accommodate them. Hybrid cars use a special fuel called pertaDEX. There used to be several gas stations here that sold it, but then it decreased to only three. Now its only sold in jerrycans. The stations think, Why bother building an expensive pump specially for pertaDEX when only a few [motorists] buy it? he said. I think we have a long way to go before seeing hybrid cars cruising on our streets because its too complicated. For now, the government should just concentrate on upgrading emission standards for the country, since we are currently still adopting the Euro 2 standard. Currently, emissions of nitrogen oxides, total hydrocarbons, non-methane hydrocarbons, carbon monoxide and particulate matter are regulated for most vehicle types. European Union emission standards define the acceptable limits for exhaust emissions of new vehicles sold in EU member states. The emission standards are defined by five categories, each with increasingly stringent standards. These standards are adopted worldwide, including in Indonesia. While EU members states currently impose the highest, Euro 5, and some Asian nations are already using the Euro 4 standard, Indonesia is stuck on Euro 2. As a result, cars in Indonesia produce twice as much carbon monoxide as vehicles in some neighboring countries. In Indonesia, gas stations sell gasoline that has a high sulfur content. Even too high for the Euro 2 standard, Freddy said. Under Euro 2, sulfur in gasoline should not exceed more than 500 parts per million (ppm) per liter. In Indonesia, however, most stations sells gasoline that contains up to 3,500 ppm per liter. Higher sulfur content results in higher emissions in the form of sulfur dioxide, which can cause health problems in humans. By comparison, Japan has adopted the Euro 4 standard, and its gasoline has a sulfur content of only 10 ppm per liter. Given Indonesias pollution woes, some argue that it makes more sense to introduce vehicles here that run on compressed natural gas (CNG) instead of hybrid cars. The government should think about giving more subsidies for CNG Continued on Page 12

Driving Pollution Away With a Hybrid Car and Fuel-Efficient Practices

What Is a Hybrid Car, Exactly?

Report Dewi Kurniawati

with the Indonesian Automotive Industries Association (Gaikindo) has pleaded with the central government to give special incentives in the form of tax reductions to hybrid-vehicle buyers. If hybrids such as the Prius become more affordable, industry officials reckon, it could reduce gasoline consumption and vehicle emissions in Indonesian cities, Jakarta the largest among them. The government thus far has been unmoved by the logic. Those hybrid cars fall in the category of luxury goods, said Evy Suhartantyo, spokesman for the Directorate General of Customs. I agree on the environment argument, but if we lower the tax, please tell me who will put money in our countrys pocket? Evy did concede that the government is at least considering reducing taxes on imported hybrid vehicles, but will keep them firmly in place for other luxury cars. We have considered it, and might announce something soon enough, Evy said. However, industry officials say it shouldve been done long ago, given the environmental and economic benefits, which have prompted

s the Toyota Motor Corp. coped this year with a global recall of more than 8.5 million vehicles for dangerous defects including its popular hybrid Prius model its executives may have taken some solace in knowing they wouldnt have to worry about returns of the gaselectric car in Indonesia. They are as rare as a Javanese rhino here. Prius, the first mass-produced hybrid vehicle, first went on sale in Japan in 1997 and was introduced worldwide four years later. Hybrid cars combine a conventional internal-combustion engine with an electric propulsion system to achieve better fuel efficiency. The Prius has been ranked as among the cleanest vehicles sold in the United States based on smog forming and toxic emissions, and is currently available in more than 40 countries and regions. Nearly 2 million people worldwide drive this environmentally friendly sedan. But not, of course, in Indonesia. Despite its global popularity and fuel efficiency, there are only 13 Prius vehicles on the countrys streets, eight of them in Jakarta. Another 10 Toyota-produced Lexus hybrid vehicles are on order. Thats a sad showing for a country that ranks eighth in car sales in Asia. The obvious question is: Why are there so few hybrid cars in Jakarta, given that vehicle emissions here account for 70 percent of total pollution? There is very little demand for the Prius in this country. Its a pricey car, said Achmad Rizal, chief of marketing communications for Toyota in Indonesia. In Japan or the United States, a Prius costs about Rp 300 million ($32,400), but in Indonesia the price tag is nearly double. We dont have a choice the government imposes a high tax on imported cars, and that includes the Prius, Achmad said. Since 2006, he said, Toyota along

A hybrid car is simply a car that runs on more than one type of fuel. Most run on gasoline and batteries, but some on gasoline and ethanol. The most common type of hybrid, known as a parallel hybrid, has the transmission powered by both an electric engine and an internal combustion engine. Some the full hybrids can run on just batteries, just gasoline or a combination of both, for example the Toyota Prius or Nissan Altima. Battery life is very limited. There are also series hybrids, for example the Honda Civic, where the electric part of the motor merely serves to complement and augment the gasoline engine. With this type of engine real savings in fuel use can be made, but you cannot travel on battery power alone. The gasoline engine powers a generator, which supplies electricity to run the motor. Plug-in hybrid electric vehicles (PHEVs) are hybrids that are simply plugged in to an electrical socket to charge them, like any rechargeable appliance. This allows the user to spend more time on battery power alone, particularly for short runs in

What about disadvantages? First, modern hybrids are not cheap, and batteries may need replacing after 250,000 kilometers. The batteries are also heavy, which adds to the overall weight of the cars, which may be a disadvantage to some people. Remember also that hybrids can leave a larger carbon footprint from their manufacture because of the extra components that are needed for these types of vehicles the twin drive-trains, for example.

Cant Afford a Hybrid? Learn Fuel Efficiency Instead.

city traffic. The present generation of hybrids are not plug-ins the batteries are recharged by the brakes and when the gasoline engine is in use. Flex-fuel hybrids are another coming development. They allow flexibility to use different fuel sources ethanol, biodiesel and gasoline as required or as available. The main advantage is that hybrids are cleaner than cars that run on gasoline or diesel. When full hybrids are being driven on the battery, there are zero significant emissions. The Toyota Prius leads

the field for efficiency, so far. Series hybrids still deliver some real gains; gasoline goes further, and emissions of carbon gases and nitrous oxides are much reduced. Obviously, with all this fuel efficiency, hybrids are cheaper to run, but they are more expensive to buy. Over a lifetimes use they should give real fuel economy even up to 60 miles per gallon, and the figure is rising as technological advances are made. Hybrid car batteries, usually nickel-metal hybrids, are also completely recyclable.

One of the very best ways to increase fuel economy is to drive smoothly and gently: When moving off, change up through the gears as quickly as possible so that your vehicles revs are kept low. Anticipate bends and halts so that you reduce the need for sudden braking, letting the cars friction against the road do most of the slowing for you. Try to work out your cars optimum cruising speed. Most cars will lose efficiency after about 85 kilometers per hour. Most of all, just get into the habit of not putting your foot down on the accelerator.

Plan your journeys better. Save fuel by planning short journeys to minimize traffic, traffic lights and lengthy one-way systems. Think about putting off a trip if you know traffic will be heavy. And always try to take care of multiple errands on one journey, instead of having to make individual trips for everything. Dont idle! If stopping for more than a moment or two or stuck in a queue, cut the engine where safe. Air-conditioning significantly adds to fuel consumption. Dont use it needlessly but then the drag caused by having all your windows open increases fuel consumption as much or more than air-conditioning. Keep your car clean. Its hard to believe, but dirt increases wind resistance. Studies have shown that a clean car can make a significant difference over the course of a year. It is worth making sure that your car is at least well maintained, which will help in the quest for increasing fuel economy. Filters should be changed regularly, the right oil used, engine tuned, fan belt kept tight, tires correctly inflated and wheel alignment and balance checked. Tips courtesy of GreenFacts.com

Weird wheels: The new Toyota Plug-In Hybrids battery pack. The Prius is popular worldwide, but high import taxes keep it a rarity in Indonesia. Bloomberg Photo

Corporate Social Responsibility Profile ( Advertorial)

The Indonesian government should give incentives to hybrid car owners, just like elsewhere

Freddy Sutrisno, Indonesian Automotive Industry Association

A Transjakarta bus waiting to fill up with compressed natural gas. JG Photo/ Afriadi Hikmal

many other countries from North America to Europe to Japan to give tax breaks for hybrids. The Indonesian government should give incentives to hybrid car owners, just like elsewhere, said Freddy Sutrisno, secretary general of Gaikindo. More than 70 percent of Indonesians can only afford to buy cars within a price range of a maximum of Rp 200 million, and thats exactly why we wont see too many hybrid cars on the streets. People simply cant afford it. Price is just one thing thats keeping Jakarta from becoming a greener city in India, the Reva electric car sells for as little as $6,000 and there is nothing comparable here. Another is that of the 500,000 new cars sold annually in Indonesia, more than 30 percent are in the capital, meaning more emissions each year and more cars idling on Jakartas congested roads. The Mekatronic and Electric Power Research Center in Bandung, and Yogyakartas Gadjah Mada University have both unveiled Indonesian prototype gas-electric hybrid cars, but unless investors come forward, they may never be seen on the street. Industry minister MS Hidayat has said that representatives of Japans four major automobile producers have all expressed interest in producing low-cost, eco-friendly vehicles here for as little as Rp 70 million each but to date no deal has been signed. Even if the government changes its mind on the luxury tax on imported hybrids, Freddy said, the

12

Green Jakarta

Jakarta Globe Monday, June 21, 2010

Monday, June 21, 2010 Jakarta Globe

Green Jakarta

13

Officials checking car exhausts with an emissions test. Below, the hologram emissions sticker. EPA, JG Photos

Green Garbage

How to Dump Our Dirty, Throwaway Culture

Tackling one of Jakartas most mountainous problems

From Page 10 than regular fuel, like they have in the past, said Ridwan Panjaitan, head of the law enforcement division at the Jakarta Environmental Management Board. Emissions from vehicles contribute 70 percent of total [air] pollution, and since most people cant afford to buy hybrid cars, its a cheaper option to convert from fuel to CNG. Compressed natural gas is a fossil-fuel substitute for gasoline, diesel, and propane fuel. Compressed and largely made from methane, it does produce greenhouse gases, but its cleaner than other fuels. It is increasingly common in public vehicles in Asia that have had their engines converted for CNG use. In Jakarta, the busways buses run on CNG, and have ever since the system began operations in 2005. In 2008, then-vice president Jusuf Kalla said provincial governments would soon be required to convert all public buses and taxis to CNG as part of a drive for cleaner energy. The program appears, however, to have foundered. Meanwhile, tens of thousands of gasoline-powered public buses spew out choking black smoke. And a plan to replace the citys fleet of noisy, dirty three-wheeled bajaj with new CNG-fueled models also ran afoul of the luxury tax last year and it is unclear whether the new bajaj will prevail. If we encourage public buses and private cars to convert to CNG, we would witness a significant reduction in emissions, said Ridwan from the environmental management board, noting that converter kits only cost Rp 10 million. After that, we mustnt forget to add more CNG stations on the streets so people have easy access. Currently, there are only seven CNG stations in Jakarta. If the government goes down the route of hybrid cars such as the Prius to fight pollution, analysts said, it must give import tax exemptions or reductions, in addition to reducing the sulphur content of gasoline and having stricter emissions checks. Its not an easy task. One city official said when asked about current emission checks that bus operators routinely rent equipment to help pass the cityregulated emission test. After they pass, they give the equipment back. Its a business and very hard to stop, said the official.

Why Emissions Testing Is Such a Dirty Business

gus Santosa was surprised to see a new hologram sticker in the corner of his cars front windshield after he went for a general inspection at his local garage. Apparently they conducted an emissions test on my car, he said, somewhat puzzled because he hadnt asked for one. Not that Santosa was complaining: the test was quick, cheap and best of all, his car passed. Good, so now I know that my car is in good condition, he said, smiling. I heard that the Jakarta administration wont let cars that dont have this sticker onto the main streets. Well, at least in theory. In 2005, Jakarta Governor Sutiyoso issued a regulation aimed at curbing air pollution in the capital, which requires all vehicles to undergo a yearly emissions test. The goal is to reduce the amounts of pollutants from vehicles: presumably there are excessive levels, though officials dont have the equipment necessary to measure total citywide emissions. To support this program, 300 garages across Jakarta were appointed as official emissions testing centers. The test takes less than 30 minutes, and costs about Rp 56,000 ($6). The alternative for vehicle owners is up to six months in prison or a Rp 50 million fine. Although on paper the penalty is harsh, I cant say the program has worked. Very few people are abiding by the regulation, said Ridwan Panjaitan, head of the law enforcement division at the

Jakarta Environmental Management Board. He says city police are not authorized to ticket motorists whose vehicles dont have an emissions sticker because the gubernatorial regulation conflicts with the Criminal Code on punishments for offenders.

For any crime involving more than three months jail, you have to go through a long process as required by the Criminal Code, Ridwan said. This means the Jakarta administration would have to file legal cases against offenders with the city police, he says, which would involve the district attorney, lawyers, judges and an endless string of trials. You can see that its just too complicated, he said. Because its also difficult to go back and revise the existing gubernatorial regulation, the Jakarta administration is considering a plan to entice people by offering occasional free emissions tests. Its still in the planning stage, Ridwan said. The Jakarta Environmental Management Board has attempted to be proactive, touting the benefits of emissions testing. If they check their vehicles regularly, the vehicles will always be in good condition, which will result in less pollution in the city, and they will also save fuel, Ridwan said. Last year, the board began issuing warnings about public places in Jakarta that require vehicles to have an emissions sticker to enter or park. There are now 34 locations across the city enforcing this rule, including the parking area around the National Monument (Monas), shopping malls and government offices. However, numerous problems remain. Ridwan says that while its easier to get private vehicle owners to get an emissions test because they have a sense of belonging

toward their cars, that sentiment is not shared by public bus drivers toward their vehicles. Public buses are regularly checked by the Jakarta Transportation Agency and are often declared OK. However, when we perform impromptu checks on the road, almost 90 percent of them fail, Ridwan said, declining to comment on whether there was corruption involved in the emissions testing of public buses. According to Riza Hasyim, deputy chief of the transportation agency, emissions are just one of nine items tested on public buses. We check those buses every

Report Joe Cochrane & Matthew Theunissen

six months, and there are sanctions if they fail to pass any of those nine items, he said. Riza declined to comment on claims by the Jakarta Environmental Management Board that 90 percent of public buses failed roadside emissions tests, only saying that we perform our checks according to our standards. But there are ways around the tests it, as the Jakarta Globe learned from Governor Fauzi Bowo himself. He said a private auto service station next door to the emissions and inspection center rented out parts by the hour so buses, Metro-Minis and Kopajas could pass inspection. Dewi Kurniawati

he garbage dump landslide that flattened dozens of homes in the town of Cimahi, West Java, on Feb. 20, 2005, killing 147 people, still weighs heavily on the minds of residents. Every year, mourners gather at the now-closed dump site, which used to handle waste from the nearby provincial capital, Bandung, to dutifully commemorate the disasters anniversary. While survivors still complain that the dump hasnt been rehabilitated for other economic or community uses, others say the disaster has in its own way spurred Cimahi to take measures to protect its future. Mayor Itoc Tochija notes that the city of 600,000 now recycles more than 30 percent of its organic waste, rather than throwing it into a temporary landfill. This [accident] was an inspiration for us, he said, claiming that by 2012 the city would be recycling 100 percent of its organic waste into commercial fertilizer for farming and briquets to fire the machinery of nearby factories. Cimahi learned its lesson with garbage the hard way, and its a lesson that Jakarta might want to heed. According to Tochija, staff members working at Cimahis garbage drop-off centers separate all organic waste and even some non-organic waste such as bottles for recycling, while the remaining trash is hauled by truck to the landfill. As a result, the city is forced to deal with a lot less garbage. This type of effort explains why Cimahi in 2009 won an Adipura Award, which recognizes the countrys top 100 green cities. Jakartas waste management system is the polar opposite of what is happening in Cimahi. In the capital, private garbage collectors

The Bantar Gebang landfill is already 30 percent beyond capacity, and that will only get worse as Jakarta continues to grow and produce more waste. JG Photo

haul solid waste to the citys 1,200 drop-off stations, along the way remixing recyclable and nonrecyclable materials previously separated by private households and businesses. Staff members at the drop-off stations then throw the whole lot into trucks bound for the citys two landfills, where any recycling that takes place is left to scavengers in Bekasi and Tangerang.

Meanwhile, private trash collectors sometimes just dump the garbage wherever they can to save on gasoline costs to get to the drop-off centers, which helps explain why up to 20 percent of the 6,250 tons of daily waste produced by the city ends up clogging its rivers, canals and waterways. Given the scope of Jakartas garbage problems, its time to start thinking outside the box. The

Bantar Gebang landfill in Bekasi, for example, is already operating at 30 percent beyond its capacity, and as the capitals population grows and its business and industrial sectors expand, there will only be more solid waste to deal with. Risyana Sukarma, an environmental consultant at the World Bank, says Jakarta simply lacks the infrastructure to deal with its trash effectively, and its

We can have a win-win situation: the people and the government get a cleaner city, and the private sector makes money

The administration has made efforts to encourage recycling, but most of the work is being carried out by private companies. Antara Photo/Fanny Octavianus

collection, transportation and disposal methods in particular fall short of meeting standards set by the Kyoto Protocol. That said, each of these problem areas has presented an opportunity for private sector investors who are now trying to cash in on the citys untapped urban mines. One such company is PT Godang Tua Jaya, which manages Bantar Gebang and is building three intermediate treatment facilities on site. The company acted after a plan by the Jakarta administration dating back to 1997 to build an intermediate treatment facility in each of the citys five municipalities to ease pressure on Bantar Gebang fell apart due to public opposition. So Godang Tua Jaya is filling the void by building one facility to turn organic waste into compost, a second to recycle glass, plastic and cardboard, as well as a power plant fuelled by methane gas. The plant will eventually produce 26 megawatts of power, but will initially churn out two megawatts after it opens this month. Godang Tua Jaya will sell the Continued on Page 14

Douglas Manurun

14

Green Jakarta

Jakarta Globe Monday, June 21, 2010

Monday, June 21, 2010 Jakarta Globe

15

Making A World of Difference Down in The Dumps

Its not just companies that have learned how to make money from Jakartas garbage. A curious but determined Jakarta cult commonly known as garbage scavengers have been doing it for decades. There are an estimated 400,000 trash pickers scouring the citys garbage dumps and the trash bins and dumpsters of buildings, shopping malls and private residences collecting recyclable plastics, paper, glass and metals and anything else that can be resold. While the work is not encouraged by nongovernmental organizations or the Jakarta administration, it is one of the citys few reliable recycling systems. But far from being respected, scavengers work in filthy, sometimes dangerous, conditions, are poorly paid, stigmatized and seen as a public eyesore. Most trash pickers dont have official Jakarta ID cards so are unable to find other types of employment. Their lives depend on collecting enough resalable garbage each day. Theres a scavenger society within the citys two landfills, while solitary trash pickers are seen sifting through residential garbage bins or pulling makeshift wooden carts holding their booty. A scavengers typical day begins so early that by the time most of Jakarta is awake its garbage bins have already been picked clean of valuable refuse. Pak Udin, a trash picker in Cirendeu, South Jakarta, sets off at 4 a.m. each day with his cart. He and about 70 others from his neighborhood get daily briefings from the leader of their trash pickers collective, who is a waste trader, on what materials they should keep an eye out for. One recent morning, Udin looked specifically for plastic Aqua mineral water bottles, but if he finds other valuable refuse, such as copper, hell grab it as well. Once his cart is full, he takes his booty back to his boss, who sells it to manufacturing companies. Although the work is hard and hes looked down upon, Udin says he earns better money than when he worked as a laborer on construction sites. There is always income as a trash picker there is no shortage of trash in this city, he says. He has been working for his boss for more than 30 years and is happy with the arrangement. However, given that scavenging is an informal

Continued from Page 13 power back to the city, completing a full circle of shared responsibility for solid waste. More important, it is estimated that the three new facilities will eventually reduce the amount of waste being dumped into the Bantar Gebang landfill by 2,000 tons per day by 2023. The government cant work by itself, and private companies cant work by themselves, said Douglas Manurun, Godang Tua Jayas managing director. Together, we can have a win-win situation: the people and the government get a cleaner city, and the private sector makes money. Godang Tua Jaya has teamed up with another private company, PT Navigat Organic Energy, to invest Rp 600 billion ($66 million) to build the three facilities, which they expect to bring a high return. If it wasnt profitable for us, then we wouldnt do it, Manurun said. Another private company making greenbacks by making Jakarta more green is Geocycle, a branch of international cement producer Holcim. Geocycle, which produces about 5.5 million tons of cement in Indonesia annually, collects and then incinerates about 20,000 tons of solid waste a month as part of its cement-making process. The waste is burned in a kiln at temperatures of up to 2,000 degrees Celsius and reduced to ash, which is then blended into its cement mixture. This process neither produces residue nor does it degrade the quality of the cement whatsoever, says Vincent Aloysius, manager of Geocycle Indonesia. The company is also looking at using human waste in the making of its cement, a process that is already being done at its plants in Europe, Aloysius says. The World Banks Sukarma says environmentally sound companies like Geocycle are beginning to have a noticeable impact on the citys waste problems, but they alone arent the solution. Industrial waste, he says, only accounts for about 20 percent of Jakartas total, with the vast majority coming from household garbage. Ultimately, the key to tackling Jakartas solid waste problems is to educate the population about sustainable waste management, he says. But creativity should count for something.

Green Hero The Recycling Man

Turning the Citys Trash Into Treasure

Have You Missed Any Of Our Other Special Issues on Jakarta?

Why does Jakarta's Old Town seem to be crumbling before our eyes? How slow planning, red tape and inertia is jeopardizing the capital's biggest historical legacy.

Scavengers work in filthy and often dangerous conditions. They are paid a pittance and are often seen as a blight on society. But for all their negative image, they provide one of the citys few reliable recycling systems. JG Photo/Jurnasyanto Sukarno