Professional Documents

Culture Documents

C ccc9c: CC CCC CCC Ghatth L Flat Aatnt A Lafallacy

C ccc9c: CC CCC CCC Ghatth L Flat Aatnt A Lafallacy

Uploaded by

johnmackendrickOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

C ccc9c: CC CCC CCC Ghatth L Flat Aatnt A Lafallacy

C ccc9c: CC CCC CCC Ghatth L Flat Aatnt A Lafallacy

Uploaded by

johnmackendrickCopyright:

Available Formats

Fallacy: a deceptive, misleading, or false notion, belief, etc.

-That the world is flat was at one time a popular fallacy. - deceptive, misleading, or false nature; erroneousness.

Fun with Fallacy: The Sin and Art of Nonsense

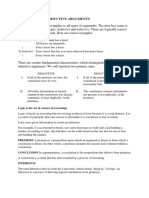

Logical fallacies are the sins of the world of reason. Just as with sin in the world of morality, in the world of reason we all fall into fallaciousness sometimes - whether by accident or on purpose. And, like sin, logical fallacy can "work" in the interpersonal world, but it fails against harder realities every time. The study of logical fallacy is the interesting, backdoor approach to thinking about logic and reasoning. It is difficult for us amateurs to define "logical" except to say that it exists where there is no illogicality which is a Circular Fallacy. In a rational universe, none of us should be permitted to offer an opinion on anything without first making a study of logical fallacy. But, no one said that this was a rational universe. Everyone seems to have their favorite bugaboo fallacies, and everyone also seems to have their favorite fallacies to use in debate, manipulation, persuasion, and discussion. (In politics, outright lying seems often to be the preferred mode of disputation, but we are dealing here with subtler matters: errors of which the user is often not aware, but also the deliberate abuse of logical errors to score points, to persuade, or to bamboozle.) (1) Retrospective Determinism: The fallacious notion that because something did happen, it was bound to happen. "9-11 was inevitable because..." Colloquially known as 20/20 hindsight. (2) The Fallacy of the Single Cause: The fantasy that events have simple or single "causes." Eg, "What was the cause of World War One?" (3) Ipse Dixit: Argument from authority rather than from data. Eg, "The New York Times says...," All of the above, and many more, can be found in more detail at logicalfallacies.com, or Wikipedia.com. the most effective fallacious arguments can be made by combining or sequencing two or more fallacies, thus overwhelming the logical capacities and scrambling the brains of your helpless victim. Indeed, they rarely occur in pure form anyway. Sad to say, sometimes one must use fallacies for persuasion - even when cogent logic is on your side - because fallacies can often be more persuasive than fact or logic to the uninitiated (such as jurors, voters, and newspaper readers). Hence, the lowly reputations of politicians and lawyers. Aristotle may have been the first (no surprise - he was the first to organize everything - an obsessional genius) to list logical fallacies in his Sophistical Refutations, in which he listed thirteen.

(4) Begging the Question

Explanation: Begging the Question is a fallacy in which the premises include the claim that the conclusion is true or assume that the conclusion is true. This sort of "reasoning" is fallacious because simply assuming that the conclusion is true in the premises does not constitute evidence for that conclusion. Obviously, simply assuming a claim is true does not serve 1

as evidence for that claim. This is especially clear in particularly blatant cases: "X is true. The evidence for this claim is that X is true." Some cases of question begging are fairly blatant, while others can be extremely subtle. Examples 1. "If such actions were not illegal, then they would not be prohibited by the law." 2. Interviewer: Bill: Interviewer: Bill: Your resume looks impressive but I need another reference." "Jill can give me a good reference." "Good. But how do I know that Jill is trustworthy?" "Certainly. I can vouch for her."

(5) Ad Hominem (Personal Attack)

Explanation: It is important to note that the label ad hominem is ambiguous, and that not every kind of ad hominem argument is fallacious. In one sense, an ad hominem argument is an argument in which you offer premises that you the arguer doesnt accept, but which you know the listener does accept, in order to show that his position is incoherent . Arguments of this kind focus not on the evidence for a view but on the character of the person advancing it; they seek to discredit positions by discrediting those who hold them. It is always important to attack arguments, rather than arguers, and this is where arguments that commit the ad hominem fallacy fall down. Example: (1) William Dembski argues that modern biology supports the idea that there is an intelligent designer who created life. (2) Dembski would say that because hes religious. Therefore: (3) Modern biology doesnt support intelligent design. This argument rejects the view that intelligent design is supported by modern science based on a remark about the person advancing the view, not by engaging with modern biology. It ignores the argument, focusing only on the arguer; it is therefore a fallacious argument ad hominem.

(6) Non sequitur

Explanation: Non sequitur (Latin for "it does not follow"), in formal logic, is an argument in which its conclusion does not follow from its premises. In a non sequitur, the conclusion can be either true or false, but the argument is fallacious because there is a disconnection between the premise and the conclusion. All formal fallacies are special cases of non sequitur. The term has special applicability in law, having a formal legal definition. Many types of known non sequitur argument forms have been classified into many different types of logical fallacies.

(7) Hasty generalization

Explanation: Hasty generalization is the fallacy of insufficient statistics, fallacy of insufficient sample, fallacy of the lonely fact, leaping to a conclusion) Person A travels through Town X for the first time. He sees 10 people, all of them children. Person A returns to his town and reports that there are no adult residents in Town X. Person A and Person B walk past a pawn shop. Person A remarks that a watch in a window display looks like the one his grandfather used to wear. On the basis of this remark, Person B concludes that: Person A's grandfather pawned his watch; or Person A's grandfather had expensive tastes in jewelry; Context is also relevant; in mathematics the Plya conjecture is true for numbers less than 906,150,257, but fails for this number. Assuming something to be true for all numbers when it has been shown for over 906 million cases would not generally be considered hasty, but in mathematics a statement remains a conjecture until it is shown to be universally true. Hasty generalization is also the basis for racist beliefs and prejudices - a person will infer an attribute to be common to all members of a group based on knowledge of only a small sample size of that group. For example, the belief that a given person who is Jewish will be a greedy, nit-picky, stingy miser or the belief because a person is black, (s)he will be loud, poor, and criminal.

So why learn logical fallacies at all?

First, it makes you look smart. If you can not only show that the opposition has made an error in reasoning, but you can give that error a name as well (in Latin!), it shows that you can think on your feet and that you understand the opposition's argument possibly better than they do. Second, and maybe more importantly, pointing out a logical fallacy is a way of removing an argument from the debate rather than just weakening it. Much of the time, a debater will respond to an argument by simply stating a counterargument showing why the original argument is not terribly significant in comparison to other concerns, or shouldn't be taken seriously, or whatever. That kind of response is fine, except that the original argument still remains in the debate, albeit in a less persuasive form, and the opposition is free to mount a rhetorical offensive saying why it's important after all. On the other hand, if you can show that the original argument actually commits a logical fallacy, you put the opposition in the 3

position of justifying why their original argument should be considered at all. If they can't come up with a darn good reason, then the argument is actually removed from the round.

Logic as a form of rhetoric

Not every reader will immediately recognize the importance of the logical fallacy you've pointed out in your opposition's argument. Even if a logician would immediately accept the accuracy of your point, in a rhetoric it's the reader/listener that counts. It is therefore not enough simply to point out a logical fallacy and move on; there is an art to pointing out logical fallacies in your opposition's arguments. Here are a few strategies you may find useful in pointing out logical fallacies in an effective manner: 1. State the name of the logical fallacy, preferably in both Latin and English, and make sure you use the phrase "logical fallacy." Why? Because it is important to impress on the reader that there is no mere counterargument you are making, nor are you just labelling the opposition's viewpoint as "fallacious" for rhetorical effect. Stating the fallacy's Latin name helps, because some people just aren't sure something's a fallacy unless Aristotle or some other authority called it one. Say something like, "The author points out that the voters supported X by a wide margin in last year's referendum. But this is just the logical fallacy of argumentum ad populum, appeal to public opinion!" 2. Explain what the fallacy means and why it is wrong. But be careful -- you have to do this without sounding pedantic. You should state the fallacy's meaning as though you are reiterating what you assume your intelligent reader already knows. To continue the example above, say, "It doesn't matter how many people agree with you, that doesn't mean it's necessarily right." There, now you've defined for everyone what's fallacious about argumentum ad populum. 3. Give a really obvious example of why the fallacy is incorrect. Preferably, the example should also be an unfavorable analogy for the opposition's proposal. Thus: "Last century, the majority of people in some states thought slavery was acceptable, but that didn't make it so!" Finally, point out why the logical fallacy matters. "This fallacious argument should be thrown out of the debate. And that means that the opposition's only remaining argument for X is...."

You might also like

- Logical FallaciesDocument12 pagesLogical FallaciesCraig MawsonNo ratings yet

- Argument From The Debate Rather Than Just Weakening It. Much of The Time, A Debater Will RespondDocument8 pagesArgument From The Debate Rather Than Just Weakening It. Much of The Time, A Debater Will RespondNormahyatur MasNo ratings yet

- Logical Fallacies and The Art of DebateDocument10 pagesLogical Fallacies and The Art of DebatekarnsatyarthiNo ratings yet

- Logical Fallacies An Encyclopedia of Errors of ReasoningDocument8 pagesLogical Fallacies An Encyclopedia of Errors of ReasoningJulian Paul CachoNo ratings yet

- FallacyDocument36 pagesFallacyNischal BhattaraiNo ratings yet

- From Argument To AssertionDocument22 pagesFrom Argument To AssertionsuekoaNo ratings yet

- How To Think: Why Arguing A Point Comes NaturallyDocument11 pagesHow To Think: Why Arguing A Point Comes NaturallyAnonymous 0yCy6amiEmNo ratings yet

- Ad Hominem and Other FallaciesDocument9 pagesAd Hominem and Other FallaciesChris LlevaNo ratings yet

- Logical Fallacies ReportDocument14 pagesLogical Fallacies ReportJonathan Maapoy100% (1)

- Common Logical Fallacies: 1. Non SequiturDocument9 pagesCommon Logical Fallacies: 1. Non SequiturChy_yNo ratings yet

- Logical Fallacy - RationalWikiDocument26 pagesLogical Fallacy - RationalWikiJayri FelNo ratings yet

- Logical FallacyDocument9 pagesLogical Fallacybahrul.hidayah@yahoo.comNo ratings yet

- Illogical FallaciesDocument5 pagesIllogical FallaciesMaricar RamirezNo ratings yet

- Week 7-8 FallacyDocument8 pagesWeek 7-8 FallacyYsabela LaureanoNo ratings yet

- Fallacy of PresumptionDocument10 pagesFallacy of PresumptionSehrish RupaniNo ratings yet

- How To ThinkDocument13 pagesHow To ThinkmrigankkashNo ratings yet

- Fallacies PDFDocument9 pagesFallacies PDFmirradewi100% (1)

- Logic and Argument in WritingDocument6 pagesLogic and Argument in WritingCarline RomainNo ratings yet

- E. Chapter 4 PDFDocument14 pagesE. Chapter 4 PDFKingashiqhussainPanhwerNo ratings yet

- How To Win Every Argument The Use and Abuse of Logic PDFDriveDocument246 pagesHow To Win Every Argument The Use and Abuse of Logic PDFDriveAngel100% (1)

- FallacyDocument51 pagesFallacyDannyMViNo ratings yet

- Logical Fallacies and The Art of DebateDocument10 pagesLogical Fallacies and The Art of DebateRansel Fernandez VillaruelNo ratings yet

- Latin List of Logic FallaciesDocument34 pagesLatin List of Logic FallaciesMark DicksonNo ratings yet

- 10 Rules of Philosophy To Live by - The GuardianDocument5 pages10 Rules of Philosophy To Live by - The GuardianmyrikiNo ratings yet

- Deductive and Inductive ArgumentDocument6 pagesDeductive and Inductive ArgumentPelin ZehraNo ratings yet

- Critical Thinking: Inductive and Deductive Reasoning ExplainedFrom EverandCritical Thinking: Inductive and Deductive Reasoning ExplainedRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (6)

- Remarks On Epistemology: PreambleDocument8 pagesRemarks On Epistemology: PreamblebeerscbNo ratings yet

- Fallacies in ReasoningDocument3 pagesFallacies in ReasoningJames Clarenze VarronNo ratings yet

- Group Assignment 1 Eng 105Document6 pagesGroup Assignment 1 Eng 105rakibul islam rakibNo ratings yet

- Carl Sagan Kit To Critical ThinkingDocument8 pagesCarl Sagan Kit To Critical ThinkingJPNo ratings yet

- 8 Logical Fallacies That Are Hard To Spot - Big ThinkDocument18 pages8 Logical Fallacies That Are Hard To Spot - Big ThinkLegatus_Praetorian100% (1)

- Bad Arguments That Make You SmarterDocument4 pagesBad Arguments That Make You SmarterHanz Jennica BombitaNo ratings yet

- Logical FallaciesDocument14 pagesLogical FallaciesHAILE KEBEDE100% (1)

- The Word "Fallacy" Comes From The Latin "Fallacia" Which Means "Deception, Deceit, Trick, Artifice,"Document30 pagesThe Word "Fallacy" Comes From The Latin "Fallacia" Which Means "Deception, Deceit, Trick, Artifice,"Ayele MitkuNo ratings yet

- Conceptions of KnowingDocument4 pagesConceptions of KnowingKirill FilipchenkoNo ratings yet

- How To Win Every Argument (PDFDrive) - 30-36Document7 pagesHow To Win Every Argument (PDFDrive) - 30-36alfonsoNo ratings yet

- Abordo - Legal LogicDocument5 pagesAbordo - Legal LogicshariabordoNo ratings yet

- 15 Logical Fallacies You Should Know Before Getting Into A DebateDocument1 page15 Logical Fallacies You Should Know Before Getting Into A DebateSkyAbdi GNo ratings yet

- Logical FallaciesDocument39 pagesLogical Fallaciessott6100% (1)

- UNIT 3 PART 2 FallaciesDocument61 pagesUNIT 3 PART 2 Fallaciesblue velvets100% (1)

- Debate Sogie BillDocument12 pagesDebate Sogie BillLuke Edward GallaresNo ratings yet

- LOGICAL FALLACIES HANDLIST: Arguments To Avoid When Writing/ArguingDocument10 pagesLOGICAL FALLACIES HANDLIST: Arguments To Avoid When Writing/ArguingSarah Elizabeth LunasNo ratings yet

- 15 Logical Fallacies You Should Know Before Getting Into A DebateDocument5 pages15 Logical Fallacies You Should Know Before Getting Into A Debatedenmar valdepenasNo ratings yet

- Study Unit 1 Logical FallaciesDocument12 pagesStudy Unit 1 Logical FallaciesChante HurterNo ratings yet

- Ad Hominem: Argument From AuthorityDocument6 pagesAd Hominem: Argument From AuthorityRed HoodNo ratings yet

- Fallacies 2Document4 pagesFallacies 2Saltanat OralNo ratings yet

- Chapt5 EL AmDocument69 pagesChapt5 EL AmYohannes GetanehNo ratings yet

- CHAPTER 5 - FallacyDocument20 pagesCHAPTER 5 - Fallacyandualemasmare320No ratings yet

- Unity University Department of Computer Science and Msi Introduction To Philosophy (Logic)Document9 pagesUnity University Department of Computer Science and Msi Introduction To Philosophy (Logic)EliasNo ratings yet

- ArgumentfromignoranceDocument30 pagesArgumentfromignoranceJackeline VelascoNo ratings yet

- Ad Hominem: ExampleDocument4 pagesAd Hominem: ExampleJos XavierNo ratings yet

- Chapter 3 Report - Philo SocialDocument88 pagesChapter 3 Report - Philo SocialAndrew O. NavarroNo ratings yet

- Thou Shall Not Commit Logical FallaciesDocument9 pagesThou Shall Not Commit Logical FallaciesGiselle HalpernNo ratings yet

- FallaciesDocument3 pagesFallaciesvermaashleneNo ratings yet

- Deductive and Inductive Arguments: A) Deductive: Every Mammal Has A HeartDocument9 pagesDeductive and Inductive Arguments: A) Deductive: Every Mammal Has A HeartUsama SahiNo ratings yet

- Logic Fallacies: A Mind MapDocument6 pagesLogic Fallacies: A Mind MapJohn D'Alessandro100% (1)

- Logical FallaciesDocument24 pagesLogical FallaciesRoms PilongoNo ratings yet

- Eight Preposterous Propositions: From the Genetics of Homosexuality to the Benefits of Global WarmingFrom EverandEight Preposterous Propositions: From the Genetics of Homosexuality to the Benefits of Global WarmingRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (9)

- Archetype Definitions: The QuestDocument4 pagesArchetype Definitions: The QuestjohnmackendrickNo ratings yet

- Archetype Definitions: The QuestDocument4 pagesArchetype Definitions: The QuestjohnmackendrickNo ratings yet

- Style Analysis: Improving Sentence StyleDocument1 pageStyle Analysis: Improving Sentence StylejohnmackendrickNo ratings yet

- Conventional Rhetorical Classes of The EssayDocument2 pagesConventional Rhetorical Classes of The EssayjohnmackendrickNo ratings yet

- Assignment #1: Sentence Structures: (S 1 Ind. + 0 Sub.)Document2 pagesAssignment #1: Sentence Structures: (S 1 Ind. + 0 Sub.)johnmackendrickNo ratings yet

- Tone Wrods 5x8Document1 pageTone Wrods 5x8johnmackendrickNo ratings yet

- Wca M1Document1 pageWca M1johnmackendrickNo ratings yet

- The Jungle, Eng. 11A: Mackendrick, Study GuideDocument2 pagesThe Jungle, Eng. 11A: Mackendrick, Study GuidejohnmackendrickNo ratings yet

- TransitionsDocument1 pageTransitionsjohnmackendrickNo ratings yet

- 33 Tone Exercise3Document1 page33 Tone Exercise3johnmackendrickNo ratings yet

- Document Analysis ChartDocument2 pagesDocument Analysis ChartjohnmackendrickNo ratings yet

- The Jungle (Chaps. 30 Thru 31)Document1 pageThe Jungle (Chaps. 30 Thru 31)johnmackendrickNo ratings yet

- Literature Period Research Paper AP Lang. & Comp. 11: NameDocument7 pagesLiterature Period Research Paper AP Lang. & Comp. 11: NamejohnmackendrickNo ratings yet

- Fun With FallacyDocument4 pagesFun With FallacyjohnmackendrickNo ratings yet

- Literature Period Research Paper AP Lang. & Comp. 11: NameDocument7 pagesLiterature Period Research Paper AP Lang. & Comp. 11: NamejohnmackendrickNo ratings yet

- The Jungle (Chaps. 23 Thru 25)Document1 pageThe Jungle (Chaps. 23 Thru 25)johnmackendrickNo ratings yet

- 14 Terminology 2Document1 page14 Terminology 2johnmackendrickNo ratings yet

- Tone WordsDocument1 pageTone WordsjohnmackendrickNo ratings yet