Professional Documents

Culture Documents

E&I News Update 1 - 10

E&I News Update 1 - 10

Uploaded by

gpluibOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

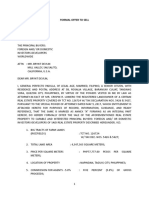

E&I News Update 1 - 10

E&I News Update 1 - 10

Uploaded by

gpluibCopyright:

Available Formats

Winter 2010

A publication of the Exemptions & Immunities Commitee of the Section of Antitrust Law, American Bar Association

IN THIS ISSUE

Message from the Editor Articles

McCarran Repeal Proposed as Part of Health Care Reform Check it Out: The Politics of Antitrust Exemptions Program Check it Out: The Petitioning and the Antitrust Laws: The Foundations of Petitioning Immunity and the Noerr-Pennington Doctrine We Want You to Become an Active and Contributing Member of the Committee

2 3

4 5 6

Special Feature

E&I Case Law Update

MESSAGE

FROM THE

EDITOR

For those of us who follow exemptions and immunities, it has been a very busy time. Congress has taken a renewed interest in immunities, focusing on immunities for railroads and insurance companies. The Courts have been active, too, with a number of decisions on a variety of immunities, particularly Noerr-Pennington and implied immunities. In this newsletter, we provide a series of short updates on recent events and previews of some upcoming programs. We also provide recent case summaries. If you want to receive these items in real time, we urge you to sign up for our list serv, where you can receive information as it develops. Of course, if you want to do more than just stay tuned, please feel free to get involved. We have projects for all levels of commitment. If you would like to volunteer, please contact John Roberti, the Committees Chair, or any of the Vice Chairs listed on page 12. John Roberti

Please send all submissions for future issues to: John Roberti Mayer Brown LLP 1909 K Street, NW Washington, DC 20006-1101 jroberti@mayerbrown.com

DISCLAIMER STATEMENT

E&I Update is published periodically by the American Bar Association Section of Antitrust Law Exemptions & Immunities Committee. The views expressed in E&I Update are the authors only and not necessarily those of the American Bar Association, the Section of Antitrust Law or the Exemptions & Immunities Committee. If you wish to comment on the contents of E&I Update, please write to the American Bar Association, Section of Antitrust Law, 321 North Clark Street, Chicago, IL 60654.

Winter 2010 Page 2

MCCARRAN REPEAL PROPOSED AS PART OF HEALTH CARE REFORM

While most of the attention over the last several months regarding the health care reform debate has centered on the public option, changes to Medicare and Medicaid, and federal funding for abortion, the possibility that the insurance industrys antitrust exemption might be repealed at least for health and medical malpractice insurershas clearly taken a back seat. However, when Congress returns from their recess in January, the McCarran-Ferguson Act will unquestionably face the strongest challenge to its continued existence ever, and significant change in the manner in which the federal antitrust laws are applied to the insurance industry is a significant possibility. historical loss data; and (c) performing actuarial services if doing so does not involve a restraint of trade. However, the bill contains two other related provisions that were added late in the process that have the potential to be equally significant. First, subdivision (b) of Section 262 expands the Federal Trade Commissions authority to bring actions under Section 5 of the FTC Act (for anticompetitive conduct) against non-profit health and medical malpractice insurers. Currently, the FTC has no such authority. Even more significantly, Section 260 of the bill permits the Federal Trade Commission to conduct studies and prepare reports concerning the entire insurance industrynot just as to health and medical malpractice insurers. Such studies and reports are also currently outside the scope of the FTCs authority. At the same time, McCarran repeal efforts advanced in the Senate, with Senator Leahy of Vermont, who has been one of the most outspoken advocates for McCarran repeal for many years, leading the charge. In September, Senator Leahy introduced a stand-alone McCarran repeal bill (S. 1681). That bill, unlike the House McCarran provision that was passed, does not contain any of the safe harbors described above. In early December, Senator Leahy offered his McCarran bill as an amendment to the Senates omnibus health care reform legislation. However, with the Senate Democrats needing all 58 Senate Democrats, plus Senators Sanders and Lieberman, to defeat a Republican filibuster and push the bill forward to passageincluding Senator Ben Nelson of Nebraska, a former insurance industry executive and a former state insurance commissionerthat was not to be. As is now well known, Senator Nelson voiced his strong condemnation for many aspects of the

The Current Status

While stand-alone bills to repeal McCarran were introduced earlier this yearas they have been many times in the pastMcCarrans continued existence took a dramatically more dangerous turn when it became ensnared in the current health care reform debate. After several Congressional hearings this Fall, which included testimony in support of repeal by Assistant Attorney General Christine Varney and Senator Harry Reid, among others, McCarran repeal was made a part of the Houses omnibus health care reform legislation (HR 3962). With the passage of the bill by the House on November 7, McCarran repeal had cleared its first hurdle. However, to the surprise of many, the legislation that was passed by the House turned out to be even broader in scope than had been anticipated. Specifically, as expected, Section 262 of the house bill would repeal McCarran for health and medical malpractice insurers with respect to all conduct except (a) collecting, compiling, classifying or disseminating historical loss data; (b) determining a loss development factor applicable to

COPYRIGHT NOTICE

Copyright 2010 American Bar Association. The contents of this publication may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, without written permission of the ABA. All requests for reprints should be sent to: Director, Copyrights and Contracts, American Bar Association, 321 North Clark, Chicago, IL 60654; FAX: 312-988-6030; e-mail: copyright@abanet.org.

Winter 2010 Page 3

Senate bill, and indicated that, unless some changes were made, he would not provide the critical 60th vote necessary for the Senate Democrats to push the Senate bill forward. One of the provisions in the bill Senator Nelson refused to support was Senator Leahys McCarran repeal amendment, and for that reason the Senate health care bill that was approved by the Senate on December 24 does not include any McCarran repeal provisions.

peal would ensure that basic rules of fair competition will apply to insurers. Moreover, Senator Leahy stated that he looked forward to working to include [McCarran repeal] when the Senate and House conference to reconcile their versions of the legislation. Accordingly, we may not yet have heard the last from Senator Leahy on this issue. Congress is in recess until January 19. At that time, because the bills passed in the House and Senate differ, a Conference Committee will likely be created that will try to harmonize the two bills for another vote in the House and Senate. While many Senators have publicly stated that any changes made to the Senate bill by the Conference Committee will make it unlikely the legislation will continue to garner the 60 votes necessary to defeat a Republican filibuster, only time will tell whether McCarran has, once again, remarkably avoided repeal.

What Happens Now?

While, for a moment, it appeared that the Senates failure to include McCarran repeal in the bill meant that McCarran had, once again, survived, any clear indication that this was in fact the case was quite short-lived. In late December, Senator Leahy issued a statement indicating his profound disappointment that McCarran repeal had not survived. He stated that McCarran repeal is an integral part of injecting competition into the health insurance market and that McCarran re-

OF

CHECK IT OUT: THE POLITICS ANTITRUST EXEMPTIONS PROGRAM

Spring Meeting, Thursday, April 22, 2010

At the 2010 ABA Antitrust Sections Spring Meeting, the Exemptions & Immunities Committee will present a program on the politics and legislative process of antitrust exemptions and immunities. Scheduled for the morning of Thursday, April 22, 2010, the program will take a close look at the politicking and process involved in Congresss recent and ongoing attempts to enact or repeal certain exemptions and immunities to the antitrust laws.The distinguished panelists on this program will consider whether more vigorous competition enforcementincluding repeal of certain insurance exemptions would assist current efforts at reforming the U.S. health care system. The program also will review legislative priorities and developments involving

exemptions and immunities in the railroad, credit card, and other industries. Program participants will include Makan Delrahim, a Partner at Brownstein Hyatt Farber Schreck LLP, as moderator, and the following panelists: W. Stephen Cannon, Chairman of Constantine Cannon LLP; Toby G. Singer, a Partner at Jones Day; Anant Raut, Counsel on the U.S. House Judiciary Committee; and Stephanie Kanwit, a health care consultant and Special Counsel for Americas Health Insurance Plans. The program is co-sponsored by the Health Care & Pharmaceuticals, Legislation, and Insurance & Financial Services Committees. Fall 2008 Page 3

Winter 2010 Page 4

OUT: PETITIONING AND THE ANTITRUST LAWS: THE FOUNDATIONS OF PETITIONING IMMUNITY AND THE NOERR-PENNINGTON DOCTRINE

IT CLE Program, Friday, February 19, 2010

An upcoming program promises fresh insight on the foundations of one of the most debated antitrust exemptions: Petitioning Immunity or the Noerr-Pennington doctrine. The Noerr-Pennington doctrine is a judicially-created policy that shields an antitrust defendant from liability for competitive injuries resulting from concerted or individual petitioning conduct that is reasonably calculated or genuinely intended to petition government decision-makers for redress. At the core of the doctrine is the conflict between two fundamental values of our democracy. On the one hand is the right of the people to petition their government for grievances, set in the foundation of our representative democracy since its inception. On the other hand is the fundamental goal of supporting our nations established economic system in which free and unfettered competition is the rule. Balancing these two core principles has been a challenge for the courts for the nearly 50 years since the Supreme Court issued its opinion in Eastern Railroad Presidents Conference v. Noerr Motor Freight, 365 U.S. 127 (1961). Courts have struggled to define the boundaries of the doctrine and to establish clear rules. This judicially created doctrine has matured over time, but continues to develop. For lower courts, balancing the core values is an arduous interpretative task. For counselors and practitioners, predicting the results is an even greater challenge. Our expert faculty will explore the foundations of petitioning immunity and provide an overview of the most important principles embodied in Noerr. The faculty includes Susan Creighton, Partner, Wilson Sonsini Goodrich & Rosati, Washington, DC. Ms. Creighton is formerly the Director of the Bureau of Competition at the Federal Trade Commission. Charles Fried, Beneficial Professor of Law, Harvard Law School, Cambridge, MA. Professor Fried is formerly the Solicitor General of the United States, an Associate Justice of the Supreme Judicial Court of Massachusetts and a leading First Amendment Scholar. David Meyer, Partner, Morrison & Foerster LLP, Washington, DC. Mr. Meyer is formerly the Deputy Assistant Attorney General for Antitrust at the United States Department of Justice. Chris Sagers, Associate Professor of Law, Cleveland Marshall College of Law, Cleveland, OH. Professor Sagers is a leading antitrust scholar who teaches classes in Administrative Law, Antitrust and Law & Economics. John Roberti, Partner, Mayer Brown LLP. Mr. Roberti is Chair of the ABA Exemptions and Immunities Committee.

CHECK

Winter 2010 Page 5

AND

WE WANT YOU TO BECOME CONTRIBUTING MEMBER OF

ACTIVE THE COMMITTEE

AN

Want to make the most of your Exemptions & Immunities Committee experience? Want to have a hand in important E&I analysis and publications? Want to forge relationships with other antitrust lawyers throughout the country? Looking for opportunities for recognition and a pathway to a leadership role in the ABA? Then become actively involved in the work of your E&I Committee. The Committee is currently seeking volunteers to help with several interesting projectsprojects that can provide you with the opportunities you seek, while making it possible for the Section and the Committee to carry out their mission to educate and support the antitrust bar. Opportunities, to name a few, include helping with a publication, writing or editing a chapter of a book to be published by the ABA; preparing articles for the Committee newsletter, the E&I Update; helping to craft comments on pending legislation in the antitrust field; participating in brown bags, teleseminars, and other presentations; and generating summaries of new cases involving exemptions or immunities, summaries disseminated to the entire Committee listserv and displayed on the Committee website with the authors byline. Just this past year, for example, the ABA published THE NOERR-PENNINGTON DOCTRINE, already listed among ABA Best Sellers, written entirely by members of the Committee. In addition, members of the Committee have been revising the ABAs STATE ACTION PRACTICE MANUAL, the first edition of which appeared in 2000; we expect that to be published soon this year. Upcoming book and publication efforts promise to be equally active, with the Committee continuing to provide annual updates to the yearly Antitrust Law De-

velopments series, and with another project just in the beginning phases, a proposed all-encompassing EXEMPTIONS & IMMUNITIES MANUAL, a onestop resource for antitrust exemptions. Recent months have seen Committee members provide testimony, or support the testimony of Section leadership, on proposed federal legislation involving statutory immunities in the railroad and healthcare industries. More activity on this front looms, and help will be needed in preparing and presenting views on behalf of the Section of Antitrust Law. And, of course, opportunities abound in the more frequent publications and informational presentations of the Committeethrough its E&I Update newsletter, brown bags (often in conjunction with other Committees of the Section), and our caselaw updates broadcast to the listserv. Each of these not only offers the chance for those involved to learn more themselves, while assisting and educating others, but also provides a platform for recognition nationally and within the Committee and Section. Each caselaw update carries an attribution naming the author and his/her law firm and city. Contributors are identified in the newsletter as Contributing Editors. Frequent participants are invited to join Committee leadership on a quarterly conference call to discuss issues important to the work and mission of the Committee. If you are interested in stepping up to join us as an active contributor to the Committee on any of these projects, or if you would just like additional information about any of them, please contact our Chairman, John Roberti, at (202) 263-3428 or jroberti@mayerbrown.com.

Winter 2010 Page 6

E&I CASE LAW UPDATE

In re Western States Wholesale Natural Gas Antitrust Litigation, MDL No. 1566, 2009 WL 3270480 (D. Nev. Oct. 12, 2009) In this consolidated multidistrict case, the federal district court for Nevada denied the defendants motion for judgment on the pleadings. Specifically, the court rejected the defendants argument that plaintiffs antitrust claims were barred by implied immunity under Credit Suisse v. Billing, 551 U.S. 264 (2007), based upon a putative plain repugnancy between plaintiffs claims and the regulatory regime established by the Commodity Exchange Act (CEA) and enforced by the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CTFC). Plaintiffs had alleged that defendants conspired to engage in a variety of activities to artificially inflate the price of natural gas for consumerse.g., by knowingly delivering false reports to trade indices (fictitious trades, altered price reports, etc.), churning, engaging in wash trades, and the likeall in violation of the antitrust laws. Defendants countered that allowing the antitrust claims to go forward would be incompatible with the [CEA] because [as was held to be true in Billing] evidence of unlawful activity would overlap with evidence of lawful activity, such [that] cases would involve complex legal line drawing which should be done by an expert agency and not by non-expert judges and juries, and that the CEA provides for limited remedies for violations of the Act which should not be circumvented through antitrust actions. The court first examined whether Congress had expressly preempted the debate by including in the CEA a savings clause that explicitly preserved antitrust claims in the area addressed by the Act. Although it found considerable evidence in the legislative history that Congress did not intend to oust completely the application of the antitrust laws to the regulated area, the court found no provision of the CEA that expressly and sufficiently specifically preserved all antitrust actions. So, the court proceeded to apply the four-part test prescribed by the Supreme Court in Billing, to determine whether antitrust actions should be deemed to have been impliedly precluded by the CEA: (1) the existence of regulatory authority under the [regulatory] law to supervise the activities in question; (2) evidence that the responsible regulatory entities exercise that authority; . . . (3) a resulting risk that the [regulatory] and antitrust laws, if both applicable, would produce conflicting guidance, requirements, duties, privileges, or standards of conduct[, and] (4) . . . the possible conflict affect[s] practices that lie squarely within an area of . . . activity that the [regulatory] law seeks to regulate.1 But the defendants motion in Western States foundered on the third Billing criterion. Contrary to the Supreme Courts determination in the securities context in Billing, the Western States court found that [n]o special expertise is required to evaluate the illegal conduct targeted there by the plaintiffs, [and] therefore courts were not likely to make unusually serious mistakes . . . such that permissible or encouraged conduct under the CEA would be deterred. The court also concluded that, unlike the setting in Billingwhere the defendant entities often needed to work as syndicates with respect to IPOsthe independent gas companies in Western States did not need to form joint enterprises to trade gas or gas futures. Further, the court held, the remedies afforded to private plaintiffs by the antitrust laws were a useful supplement to the regulatory and criminal penalties of the CEA, as enforced by the CFTC, and such antitrust litigation would not upset or conflict with the CEA enforcement scheme. There was, in sum, no disqualifying clear repugnancy or incompatibility between the regulatory scheme and the plaintiffs antitrust claims.

Winter 2010 Page 7

Consequently, the court ruled, plaintiffs antitrust claims were not impliedly repealed or precluded by the CEA. [Thanks to Ken Carroll]

Luxpro Corp. v. Apple, Inc., No. 08-CV-4092, 2009 WL 3152210 (W.D. Ark. Sept. 28, 2009) In Luxpro Corp. v Apple, the federal district court for the Western District of Arkansas recently rejected Apples motion to dismiss based on Noerr-Pennington immunity, with respect to certain letters Apple had sent to Luxpros customers after Apple had commenced litigation against Luxpro, a competitor. The court found that Apple had not shown that its post-litigation conduct of sending warning letters, making threats, and exerting pressure on Luxpros clients were [sic] incidental to the prosecution of the . . . litigation, or that its conduct was in any way related to its right to petition a court. The court did, however, ultimately dismiss most of Luxpros claims on other, non-Noerr grounds. Luxpro is a small Taiwanese corporation that produced a variety of MP3 players. In 2005 it began marketing its products to a number of outlets in countries other than the U.S. In an unfortunate maneuver, it christened one of its products the Super Shuffle, which predictably prompted Apple to seek protection of its Shuffle trademark. Apple procured an injunction from a court in Germany prohibiting Luxpro from using the name Shuffle to market any of its products. It then moved more aggressively to secure a further and much broader preliminary injunction from a Taiwanese court that prohibited Luxpro from manufacturing, distributing, or marketing any of its MP3 players pending trial. While this injunction was on appeal, Apple sent letters to various customers of Luxpro, warning them of the injunction and demanding that they cease doing business with Luxpro. Although Luxpro attacked Apples entire over-arching course of conduct in targeting Luxpro (including the filing of the lawsuits in Germany and Taiwan), it was these warning or threat letters that were the principal focus of the courts Noerr analysis. The court began by determining that Apples litigation in Germany and Taiwan did not itself fall within the sham exception to Noerr, even though the broad preliminary injunction in Taiwan was ultimately vacated on appeal. The court held that Apples claims against Luxpro in those foreign lawsuits were not objectively baseless, and therefore not sham litigation under PRE. Thus, neither the litigation itself nor the attendant threat letters were deprived of Noerr immunity on the basis of sham petitioning. (Curiously, in this analysis the court did not even address the question (discussed at pages 85-87 of the Sections new monograph on The Noerr-Pennington Doctrine) whether petitioning a foreign court should enjoy the protections of Noerr. See Coastal States Marketing v. Hunt, 694 F.2d 1358, 1366-67 (5th Cir. 1983) (finding Noerr does extend to petitioning foreign governments); ANTITRUST DIVISION, U.S. DEPT OF JUSTICE & FTC, ANTITRUST ENFORCEMENT GUIDELINES FOR INTERNATIONAL OPERATIONS, 3.34 (1995). This omission seemed the more curious when the court began its direct analysis of the threat or warning letters, themselves, by explaining that [i]t is ones right to petition the government under the First Amendment that is ultimately being protected by the Noerr-Pennington doctrinean observation seemingly more apt to petitioning a government to which the First Amendment actually applies.2 In assessing the potential immunity for Apples threat letters to Luxpros customers, the court acknowledged that pre-litigation demands and threats customarily have been accorded Noerr protection under PRE, Coastal States, Sosa v. Direct TV, 437 F.3d 923 (9th Cir. 2006), and other authorities. But, the court concluded, Apples post-litigation threat letters to Luxpros customers were distinguish-

Winter 2010 Page 8

able from the pre-litigation letters to potential defendants in Sosa, for example. Citing Laitram Machinery, Inc. v. Carnitech A/S, 901 F. Supp. 1155, 1161 (E.D. La. 1995), it held that sending such post-litigation threat letters to non-parties to the foreign lawsuits was not in any way related to [Apples] right to petition a court. It therefore denied Noerr-Pennington immunity to Apples conduct and rejected Apples motion, at least on this ground. (quoting Billing, 551 U.S. at 275-76). As was true in Billing itself, the court fairly quickly determined that the first, second, and fourth factors were satisfied.

2 1

(emphasis added)

[Thanks to Ken Carroll]

California Pharmacy Management LLC v. Zenith Insurance Co., No. SACV09-0242 DOC (FMOx), 2009 WL 3756559 (C.D. Cal. Nov. 5, 2009) California Pharmacy Management LLC v. Redwood and Casualty Insurance Co., No. SACV 09-0141 DOC (ANx), 2009 WL 3514571 (C.D. Cal. Oct. 26, 2009) In two related cases from the Central District of California, California Pharmacy Management LLC v. Zenith Insurance Co. and Znat Insurance Co., 2009 WL 3756559 (C.D. Cal. Nov. 5, 2009) and California Pharmacy Management LLC v. Redwood and Casualty Insurance Co. et al, 2009 WL 3514571 (C.D. Cal. Oct. 26, 2009), the district court declined to apply Noerr Pennington immunity to dismiss the complaints on 12(b)(6) grounds based upon the presence of lulling allegations in the amended complaints. More specifically, the court refused to rule that allegations that Defendants lulled the plaintiff into supposed good faith negotiations, plus telling other industry actors that the plaintiff was under investigationall of which predated litigation conduct that was the gravamen of the complaint and which led to the prior dismissalsgave rise to Noerr immunity absent a fuller factual record showing their relation to the immunized litigation conduct. These cases originate from the workers compensation arena. Plaintiff California Pharmacy Management (CPM) employed a physician in-office medication dispensing program which apparently involved referral fees to the physicians in exchange for direct access to the patient in the physicians office. The complaints in both actions alleged RICO violations predicated upon mail fraud and wire fraud. Factually, the complaints alleged that the defendants, various workers compensation insurers and administrators, colluded and conspired to eradicate the program, putting CPM out of business. To effectuate this scheme, the complaint alleged that the Defendants engaged in three general collective actions: 1) ceasing reimbursement to CPM; 2) delivering letters to CPM with pretextual objections to claims for payment; and 3) consolidating all CPM lien claims, over 800 in all, before the California Workers Compensation Board (WCAB), an adjudicatory body. With respect to the consolidation actions before the WCAB, Plaintiff alleged that the Defendants had no actual financial interest in the outcome of these lien adjudications. Instead, the consolidations were intended to delay reimbursements to CPM, starving it of operating funds. The original complaints in both cases went through two dismissals and amendment, one by stipulation and one by court order. In both instances, the opinions addressed the third attempt by the Plaintiff to state a cause of action, and considered a request by the Defendants to dismiss with prejudice. In the prior order of dismissal, the district court found that the amended complaint failed to state a cause of action because the exclusive focus on the Defendants exercise of their rights to contest liens

Winter 2010 Page 9

and claims before the WCAB was immunized under Noerr-Pennington. Second, the allegation of baseless objections to CPMs claims did not allege mail or wire fraud. Third, there were no allegations of concrete injury flowing from the alleged racketeering scheme. Defendants again moved to dismiss the second amended complaint on Noerr-Pennington grounds, but additional allegations caused the Court to rule that there was no Noerr immunity. More specifically, the amended complaint included lulling claimsallegations that the Defendants had lulled CPM into believing that they would negotiate in good faithand also that the Defendants communicated to other carriers and administrators that CPM was under investigation for fraud and other illegal activity. In at least one of the cases, a companion state court action explicitly asserted that CPM was engaged in unlicensed operation of a pharmacy and unlawful fee splitting and referral payments from physicians. The additional allegations removed the claim from Noerr-Pennington immunity for 12(b)(6) purposes, ruled the Court, because neither concerned petitioning activity and both predated the WCAB dispute. The opinion stated that the Court will not apply Noerr-Pennington immunity prospectively to conduct that occurred long prior to protected petitioning activity and was not in contemplation of litigation. The Court did note that it would reconsider Noerr immunity on summary judgment after discovery, to determine if the lulling activities were undertaken in anticipation of litigation. The Court also considered whether the allegations that consolidation before the WCAB was a tactic, employed by Defendants solely for delay without an actual interest in the outcome, amounted to sham litigation such that there could be no Noerr-Pennington immunity as matter of law for that conduct. The Court ruled that the sham exception was not applicable, because the Defendants had an interest in the outcome, even if that process also led to delay. [Thanks to Richard K. Fueyo]

Electronic Trading Group, LLC v. Banc of America Securities, LLC, 588 F.3d 128 (2d Cir. 2009) In Electronic Trading Group, LLC v. Banc of America Securities, LLC, the Second Circuit Court of Appeals affirmed the dismissal of the plaintiffs antitrust claim, holding that those claims were impliedly precluded by the securities laws. The plaintiff, Electronic Trading Group (ETG), was a short seller of securities. A short sale is one in which the short seller identifies a security that it believes will drop in price. The short seller then contacts a broker; pursuant to SEC regulations, the broker must locate the security requested before it can accept the short sellers order. Once the security is located, the broker loans the security to the short seller, and charges, in addition to any other fees, a borrowing fee. The short seller then sells the borrowed security in the open market. In order to complete the transaction, the short seller must then buy the security in the open market and return the newly purchased security to the broker. The borrowing fee charged by the broker is affected by the scarcity of the security at issuethe more difficult it is for the broker to locate and borrow the security, the higher the borrowing fee charged by the broker. The SEC permits a broker to develop a list of securities that are relatively easy to locate and borrow, and a list of those that are relatively difficult to find and borrow.

Winter 2010 Page 10

ETG alleged that the defendants, brokers that participated in the short selling market, conspired to charge artificially high borrowing fees by agreeing to designate certain securities as difficult to borrow and fixing minimum borrowing fees for those securities. ETG asserted that the defendants violated Section One of the Sherman Act and brought various state law claims. The United States District Court for the Southern District of New York dismissed the antitrust claim, relying on Credit Suisse Securities (USA) LLC v. Billing, 551 U.S. 264 (2007), and declined to exercise supplemental jurisdiction over the state law claims. On appeal, the Second Circuit affirmed. The general test for implied preclusion is whether the securities laws are clearly incompatible with the application of the antitrust laws in a particular context. To make that determination, the Second Circuit examined four factors identified in Billing: (1) whether the practices put at issue by the antitrust claims lie within the heartland of securities regulation; (2) whether the SEC has the authority to regulate; (3) whether there exists ongoing SEC regulation; and (4) whether there is conflict between the securities laws and the antitrust laws. The Courts examination of each factor was driven by its interpretation of the analysis set forth in Billing. As for the first factor, the Court looked to whether the underlying market activity, short selling, is within the heartland of the securities business. The Court chose to examine the allegations of the complaint at this level of generality, rather than examining whether the specific conduct at issue fixing borrowing fees and agreeing to designate hard-to-borrow securitieslay within the heartland of securities regulations because the Billing opinion looked to the broad underlying market activity. At this level of generality, even ETG recognized that short selling is market activity regulated by the securities law[s]. The Second Circuit also seemed to agree with the trial courts finding that the liquidity and pricing benefits provided by short selling supported a finding that the activities lie within the heartland of securities regulation. In its evaluation of the second factor, the Second Circuit chose an intermediate level of generality. That is, rather than looking to the practice of short selling in general, and rather than examining the specific anticompetitive conduct alleged, the Court examined whether the SEC has the authority to regulate (a) the role of the brokers in short selling, and (b) the borrowing fees charged by the prime brokers. The Second Circuit concluded that the second Billing factor weighed in favor of implied preclusion. Section 10(a) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 provides that it is unlawful to effect a short sale in contravention of the rules and regulations prescribed by the SEC, and the SEC interprets that provision as a grant of plenary authority to regulate short sales of securities registered on a national securities exchange. Further, Section 6 of the Securities Exchange Act grants the SEC the authority to permit exchanges to fix the fees charged by their members if the fees are reasonable and do not burden competition any further than is necessary or appropriate. The Second Circuit also chose an intermediate level of generality in its evaluation of the third Billing factorwhether there is evidence that the SEC exercises its authority. The Court looked to whether the SEC exercises its authority to regulate the role of brokers in short selling, and found ample evidence from a regulation adopted in 2004 and a recent SEC roundtable. The regulation, 17 C.F.R. 242.203(b)(1)(i)-(iii), provides that a broker must actually borrow the requested security, have an agreement to borrow the security, or have reasonable grounds to believe the security can be borrowed so that it can be delivered when needed, before the broker can accept a short sale order. At the time that the parties presented argument to the Second Circuit, the SEC conducted a roundtable discussion regarding securities lending and short sales. Further, ETGs complaint alleged that brokers had been fined for failing to comply with the regulation, and that federal prosecutors had begun an investigation into the brokers alleged price gouging. The Second Circuit therefore concluded that the SEC actively exercises its authority to regulate the role of brokers in short selling.

Winter 2010 Page 11

The Second Circuit then examined the fourth Billing factor, whether there was a risk that the securities and antitrust laws, if both applicable, would produce conflicting guidance, requirements, duties, privileges, or standards of conduct. To evaluate this factor, the Court focused on the anticompetitive conduct alleged, which the Court described as arrangements for borrowing fees. The Court found that there was an actual conflict and a potential conflict between the securities laws and the antitrust laws. The Court characterized ETGs claim as charging communications between brokers to designate which securities were difficult to locate and an agreement to fix the borrowing fees associated with those securities. The Court, however, found that brokers are permitted to communicate about the availability and price of securities, and it is a lot to expect a broker to distinguish what is forbidden from what is allowed. Because the Court found that the prospect of antitrust liability would act as an incentive for brokers to curb their permissible exchange of information and thereby harm the efficient functioning of the short selling market, it found that there was an actual conflict between the antitrust and securities laws. The Court also found a potential conflict because there was the possibility that the SEC will act upon its authority to regulate the borrowing fees set by the brokers. The SEC allows brokers to rely on the lists of securities that are easily borrowed in accepting a short sale order, and the SEC had noted that lists of securities that are difficult to borrow are not widely used by brokers. The Court stated that if and when such hard-to-borrow lists come into broader use, it is easy to see how they could increase the efficiency of the short selling market, in which event the SEC could move quickly to regulate the borrowing fees charged by brokers for securities appearing on such lists. The Court ruled that the potential for conflict weighed in favor of a finding of implied preclusion. The Second Circuit acknowledged that much depends on the level of particularity or generality at which each Billing consideration is evaluated, and that if it had examined the Billing factors at different levels of particularity, ETG might have succeeded. The Second Circuit also cautioned that its analysis was not intended to suggest that the level of particularity applied to each consideration in this case is prescriptive in every context. [Thanks to Gregory M. Garrett]

Winter 2010 Page 12

COMMITTEE LEADERSHIP

Chair: John Roberti Mayer Brown LLP 1909 K Street, NW Washington, DC 20006-1101 (202) 263-3428 jroberti@mayerbrown.com Council Representative: Andrew I. Gavil Howard University School of Law 2900 Van Ness Street, NW Washington, DC 20006-1154 (202) 806-8018 agavil@law.howard.edu

Vice-Chairs: James M. Burns Williams Mullen PC 1666 K Street, NW, Suite 1200 Washington, DC 20006-1200 (202) 327-5087 jmburns@williamsmullen.com Ken Carroll Carrington Coleman Sloman & Blumenthal, LLP 901 Main Street, Suite 5500 Dallas, Texas 75202 (214) 855-3029 kcarroll@ccsb.com

Gregory P. Luib Federal Trade Commission 600 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW Washington, DC 20580 (202) 326-3249 gluib@ftc.gov Mary Anne Mason Hogan & Hartson LLP 555 Thirteenth Street, NW Washington, DC 20004-1109 (202) 637-5980 mamason@hhlaw.com

Contributing Editors Peter Barile Howrey LLP 1299 Pennsylvania Ave, NW Washington, DC 20004 (202) 783-0800 BarileP@howrey.com Barbara Blank Federal Trade Commission 601 New Jersey Avenue, NW Washington, DC 20580 (202) 326-2523 bblank@ftc.gov Richard K. Fueyo Trenam Kemker 101 E. Kennedy Blvd., Suite 2700 Tampa, Florida 33602 (813) 227-7471 RKFueyo@trenam.com

Greg Garrett Tydings and Rosenberg LLP 100 East Pratt Street 28th Floor Baltimore, MD 21202 (410) 752-9767 ggarrett@tydingslaw.com Paula Garrett Lin Mayer Brown LLP 1675 Broadway New York, NY 10019 (212) 506-2215 PLin@mayerbrown.com Scott A. Westrich Orrick, Herrington & Sutcliffe LLP 405 Howard Street San Francisco, CA 94105-2669 (415) 773-4235 swestrich@orrick.com

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5819)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (845)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (348)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Code of Civil Procedure, 1908Document3 pagesThe Code of Civil Procedure, 1908mukeshranaNo ratings yet

- Gan Tuck Meng & Ors V Ngan Yin Groundnut FacDocument11 pagesGan Tuck Meng & Ors V Ngan Yin Groundnut FacRaudhah MazmanNo ratings yet

- Satel Price List October 2013Document2 pagesSatel Price List October 2013spyroszafNo ratings yet

- Seangio V ReyesDocument3 pagesSeangio V ReyesJeorge Ryan MangubatNo ratings yet

- Wilton Strickland - A Constitutional Perspective On The Gun DebateDocument2 pagesWilton Strickland - A Constitutional Perspective On The Gun DebateWilton StricklandNo ratings yet

- Zabal v. DuterteDocument3 pagesZabal v. DuterteAlthea M. SuerteNo ratings yet

- Title 3 - RPC 2 Reyes-Pub OrdDocument104 pagesTitle 3 - RPC 2 Reyes-Pub OrdEuler De guzmanNo ratings yet

- Form INC-22 HelpDocument13 pagesForm INC-22 Helpkotresh_hmkNo ratings yet

- Acca p7 Workbook Q & A PDFDocument80 pagesAcca p7 Workbook Q & A PDFLorena BallaNo ratings yet

- Microsoft Corporation v. Corel - Corel's Motion For Leave To AmendDocument81 pagesMicrosoft Corporation v. Corel - Corel's Motion For Leave To AmendSarah BursteinNo ratings yet

- Law AssignmentDocument15 pagesLaw Assignment恩盛No ratings yet

- HRAGO10 30percentDocument3 pagesHRAGO10 30percentnmsusarla999No ratings yet

- Civil Aeronautics Board vs. Philippine Airlines Case DigestDocument2 pagesCivil Aeronautics Board vs. Philippine Airlines Case DigestOwen BuenaventuraNo ratings yet

- Case Doctrines On Negotiable Instruments LawDocument1 pageCase Doctrines On Negotiable Instruments LawChloeNo ratings yet

- Industrial Dispute Resolution Mechanism (Unit IV)Document6 pagesIndustrial Dispute Resolution Mechanism (Unit IV)Deepak AanjnaNo ratings yet

- Ombudsman Vs ValerosoDocument8 pagesOmbudsman Vs ValerosoMeme ToiNo ratings yet

- Formal Offer To SellDocument7 pagesFormal Offer To SellAnonymous XPcJbR100% (1)

- Full Text Cases in Poli 2 Under Atty MedinaDocument312 pagesFull Text Cases in Poli 2 Under Atty MedinaIcee GenioNo ratings yet

- Administrative LawDocument14 pagesAdministrative Lawsaurav prasad100% (2)

- ENGEL v. VITALEDocument6 pagesENGEL v. VITALEAdan_S1No ratings yet

- IPR 1 AssignmentDocument14 pagesIPR 1 AssignmentNandini RaoNo ratings yet

- 105 People vs. ReyesDocument2 pages105 People vs. ReyesInna0% (1)

- Pil Tutorial 1Document6 pagesPil Tutorial 1DANIA ALIYYA BINTI IZATSHAMNo ratings yet

- HMNS Corporate CouponsDocument2 pagesHMNS Corporate Couponsroh009No ratings yet

- Republic V CoalbrineDocument2 pagesRepublic V CoalbrineJhoana Parica FranciscoNo ratings yet

- Digest-Philex Mining Corporation, Petitioner, vs. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, Court of AppealsDocument3 pagesDigest-Philex Mining Corporation, Petitioner, vs. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, Court of AppealsRon Chris Lastimoza100% (2)

- Republic of The Philippines Supreme Court Manila: Third DivisionDocument10 pagesRepublic of The Philippines Supreme Court Manila: Third DivisionelCrisNo ratings yet

- Oilnet Petroleum (U) Ltd. Company ProfileDocument22 pagesOilnet Petroleum (U) Ltd. Company ProfileInfiniteKnowledgeNo ratings yet

- Notes On How To File An Fir With Regard To Criminal Procedure Code of IndiaDocument11 pagesNotes On How To File An Fir With Regard To Criminal Procedure Code of IndiaKranthi ChirumamillaNo ratings yet

- BarOps Case DigestsDocument22 pagesBarOps Case DigestsAlthea Angela GarciaNo ratings yet