Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Baudelaire

Baudelaire

Uploaded by

Dani Older0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

19 views16 pagesCopyright

© Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

PDF or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

19 views16 pagesBaudelaire

Baudelaire

Uploaded by

Dani OlderCopyright:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 16

Consranrin Gurs: Inthe Res, Hyd Perk. Pen and watee-colour London, Mr. Tom Gistia.

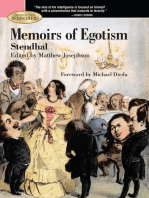

THE PAINTER OF

MODERN LIFE

AND OTHER ESSAYS

BY

CHARLES BAUDELAIRE

TRANSLATED AND EDITED

BY JONATHAN MAYNE

PHAIDON PRESS

THE PAINTER OF MODERN LIFE

I, BEAUTY, FASHION AND HAPPINESS

‘Ture world—and even the world of artists —is full of people who can go

to the Louvre, walk rapidly, without so much as a glance, past rows of

‘very interesting, though secondary, picture, to come to a rapurous halt

in front of a Titian or a Raphael—one of those that have been most

populatized by the engraver’s art; then they will go home happy, not a

few saying to themselves, ‘I know my Museum,” Just as there are people

‘who, having once read Bossuet and Racine, fancy that they have mastered

the history of literature.

Fortunately from time to time there come forward tighters of wrong,

critics, amateurs, curious enquirers, to declare that Raphael, or Racine,

does not contain the whole secret, and that the minor poets too have

something good, solid and delightful to offer; and finally that however

much we may love general beauty, a it is expressed by classical poets and

artists, we are ao less wrong t0 neglect pertinuler beauty, the beauty

of circumstance and the sketch of manners.

It must be admitted that for some years now the world has been

mending its ways a little. The value which collectors today attach to

the delightful coloured engravings of the last century proves that a

reaction has set in in the direction where it was required; Debucourt,

the Saint-Aubins and many others have found theis places inthe diction

ary of artists who are worthy of study. But these represent the past: my

‘concern today is with the painting of manners of the present. The past

is interesting not only by reason of the beauty which could be distilled

from it by those artists for whom it was the present, but also precisely

because it is the past, for its historical value. Ie is the same with the

present. The pleasure which we derive from the representation of the

present is due not only to the beauty with which it can be invested, but

also to its essential quality of being present.

T have before me a seties of fashion-plates! dating from the

+ Eacly in 1859 Baudelaire was writing to is fiend and publisher Poulet Malasis, to

‘thank him for sending him fhion-pates.

. eee

‘evolution and finishing m¢ less with

te ining ah te. Th

air rone, se

ither into beauty or ugliness; in

thing of its ghostly attraction, the past wi

TEan impartial student were to

costume, fom the sen ok through the who ange of French

county unt the present dy, he

bes cbc a ro sup him. The transitions veal

arclated as they avin the told bn

would not be a single gap: and thus, Serie

si een oe

cheats ete

curiae,

BES cmemnnnnyns

Gathmere shaw became fashionable in

‘The Painter of Modern Life 3

‘what 2 profound harmony controls all the components of history, and

that even in those centuries which seem to us the most monstrous and

the maddest, the immortal thirst for beauty has always found its satis-

faction

This is in fact an excellent opportunity to establish a rational and

historical theory of beauty, in contrast to the academic theory of an

‘unique and absolute beauty; to show that beauty is always and inevitably

of a double composition, although the impression that it produces is

single—for the fact that itis difficult to discern the variable elements of

beauty within the unity of the impression invalidates in no way the

necessity of variety in its composition. Beauty is made up of an eteznal,

invariable element, whose quantity itis excessively difficult to determine,

and of a relative, circumstantial element, which will be, if you Ike,

‘whether severally or all at once, the age, its fashions, its morals, its

emotions. Without this second element, which might be described as

the amusing, enticing, appetizing icing on the divine cake, the fist

clement would be beyond our powers of digestion or appreciation,

neither adapted nor suitable to human nature. I defy anyone to point to 2

single scrap of beauty which does not contain these two elements.

Let me instance two opposite extremes in history. In religious art the

duality io evident at the frst glance; the ingredient of eternal beauty

reveals itself only with the permission and under the discipline of the

religion to which the artist belongs. In the most frivolous work of a

sophisticated artist belonging to one of those ages which, in our vanity,

‘we characterize as civilized, the duality is no less to be seen; atthe same

time the etemnal part of beauty will be veiled and expressed if not by

fashion, at least by the particular temperament of the artist. The duality

‘of art isa fatal consequence of the duality of man. Consides, if you will,

the etetnally subsisting portion as the soul of art, and the variable clement

as its body. That is why Stendhal—an impertinent, teasing, even adis-

agzeeable critic, but one whose impertinences are often a useful spur to

seflection—approached the truth more elosely than many another when

hae said that ‘Beauty is nothing else but a promise of happiness.” ‘This

Acfinition doubtless overshoots the mark; it makes Beauty far too

subject to the infinitely variable ideal of Happiness; it strips Beauty too

2 Geépet refers to De Amour, chap. XVI; ef also the footnote in chap. 110 of the

Histoire de la Pentre Tile “a bead est Vexprestion d'une certaine manitce

Inabituelle de chereher le bonheur”

You might also like

- Young Throwing Like A Girl Twenty Years Later PDFDocument5 pagesYoung Throwing Like A Girl Twenty Years Later PDFRodrigo ChaconNo ratings yet

- Colour Study: Henry HenscheDocument193 pagesColour Study: Henry HenscheFrank Hobbs100% (12)

- Beyond Fragmentation - Collage As A Feminist Strategy by Gwen RaabergDocument20 pagesBeyond Fragmentation - Collage As A Feminist Strategy by Gwen Raabergmeganwinstanley2001No ratings yet

- The Skeptical Review Volumes 1-13Document2,049 pagesThe Skeptical Review Volumes 1-13api-3766098100% (6)

- To Take Paper, To Draw, by John BergerDocument4 pagesTo Take Paper, To Draw, by John BergerFrank Hobbs100% (2)

- To Take Paper, To Draw: A World Through LinesDocument4 pagesTo Take Paper, To Draw: A World Through LinesFrank HobbsNo ratings yet

- Hans Blumenberg Shipwreck With SpectatorDocument64 pagesHans Blumenberg Shipwreck With Spectatormfraser0613100% (2)

- Paul de Man Aesthetic IdeologyDocument206 pagesPaul de Man Aesthetic IdeologyMentor KaçiNo ratings yet

- To Take Paper, To Draw: A World Through LinesDocument4 pagesTo Take Paper, To Draw: A World Through LinesFrank HobbsNo ratings yet

- Best Teen Writing 2010Document305 pagesBest Teen Writing 2010Lucyana RandallNo ratings yet

- 1 - Lukacs - Narrate or DescribeDocument21 pages1 - Lukacs - Narrate or DescribeMutability100% (6)

- Freud Medusa's HeadDocument2 pagesFreud Medusa's Headmadeehamaqbool73620% (1)

- Erwin Panofsky, The History of Art As A Humanistic DisciplineDocument12 pagesErwin Panofsky, The History of Art As A Humanistic DisciplineMilan PopadicNo ratings yet

- Carlo Ginzburg - Making Things Strange PDFDocument21 pagesCarlo Ginzburg - Making Things Strange PDFMatías ButelmanNo ratings yet

- Pictorial Cues in Art and in Visual PerceptionDocument36 pagesPictorial Cues in Art and in Visual PerceptionFrank Hobbs100% (2)

- Perspective Drawing Handbook-JosephDAmelioDocument98 pagesPerspective Drawing Handbook-JosephDAmelioBreana Melvin100% (63)

- CELTA Assignment 3 - SkillsDocument16 pagesCELTA Assignment 3 - SkillsHazel Fernandes75% (20)

- Architecture of OFF MODERNDocument80 pagesArchitecture of OFF MODERNsaket singhNo ratings yet

- Cold War Games and Postwar Art by Claudia Mesch (2006)Document15 pagesCold War Games and Postwar Art by Claudia Mesch (2006)Anonymous yu09qxYCMNo ratings yet

- Craig Owens: Representation Appropriation and PowerDocument15 pagesCraig Owens: Representation Appropriation and PowerKarla Ljubičić100% (1)

- Beautiful SufferingDocument3 pagesBeautiful SufferingCara MurphyNo ratings yet

- Abigail Solomon-Godeau - The Azoulay AccordsDocument4 pagesAbigail Solomon-Godeau - The Azoulay Accordscowley75No ratings yet

- Etienne Balibar Citizen Subject PDFDocument2 pagesEtienne Balibar Citizen Subject PDFJenniferNo ratings yet

- Michael Leiris, "The Sacred in Everyday Life"Document4 pagesMichael Leiris, "The Sacred in Everyday Life"acephale00No ratings yet

- The Elegiac World in Victorian PoetryDocument2 pagesThe Elegiac World in Victorian PoetryLouis GoddardNo ratings yet

- Mike Kelley, Playing With Dead Things, Essay From The Uncanny, 1993 PDFDocument16 pagesMike Kelley, Playing With Dead Things, Essay From The Uncanny, 1993 PDFdestroyallmonstersNo ratings yet

- Bibliografía Paul de ManDocument16 pagesBibliografía Paul de ManMachucaNo ratings yet

- Prosthetic MemoryDocument27 pagesProsthetic MemoryDavid ClarkNo ratings yet

- Tracing Shadows: Reflections On The Origins of PaintingDocument12 pagesTracing Shadows: Reflections On The Origins of PaintingFrank Hobbs100% (1)

- The Training of The Memory in ArtDocument247 pagesThe Training of The Memory in ArtTancredi ValeriNo ratings yet

- Merleau Ponty - Eye and The MindDocument9 pagesMerleau Ponty - Eye and The MindFernanda_Pitta_5021No ratings yet

- Greenberg Modernist PaintingDocument4 pagesGreenberg Modernist PaintingTim StottNo ratings yet

- De Man, Aesthetic Formalization in KleistDocument17 pagesDe Man, Aesthetic Formalization in KleistSteven MillerNo ratings yet

- +boris Groys - The Curator As Iconoclast.Document7 pages+boris Groys - The Curator As Iconoclast.Stol SponetaNo ratings yet

- Primitivism and The OtherDocument13 pagesPrimitivism and The Otherpaulx93xNo ratings yet

- Benjamin On Surrealism - The Last Snapshot of The European IntelligentsiaDocument8 pagesBenjamin On Surrealism - The Last Snapshot of The European IntelligentsiaScribdkidd123No ratings yet

- Blanchot Dread To LanguageDocument11 pagesBlanchot Dread To Languagegokc_eNo ratings yet

- Adorno - The Actuality of PhilosophyDocument7 pagesAdorno - The Actuality of PhilosophysdflbcNo ratings yet

- Foster Hal 1995 The Artist As Ethnographer-1Document11 pagesFoster Hal 1995 The Artist As Ethnographer-1Carolina RiverosNo ratings yet

- Buchloh Figures of Authority PDFDocument31 pagesBuchloh Figures of Authority PDFIsabel BaezNo ratings yet

- Physicality of Picturing... Richard ShiffDocument18 pagesPhysicality of Picturing... Richard Shiffro77manaNo ratings yet

- Edgard Wind PDFDocument23 pagesEdgard Wind PDFMarcelo MarinoNo ratings yet

- Alois Riegl Art Value and Historicism PDFDocument13 pagesAlois Riegl Art Value and Historicism PDFJúlio Martins100% (2)

- Analytic Approaches To Aesthetics (Oxford Bibliography)Document15 pagesAnalytic Approaches To Aesthetics (Oxford Bibliography)Wen-Ti LiaoNo ratings yet

- The Verbal IconDocument10 pagesThe Verbal IconKristina Nagia0% (1)

- Towards A Newer LaocoonDocument7 pagesTowards A Newer LaocoonOranje LwinNo ratings yet

- DAMISCH, Hubert - The Origin of Perspective Part1 PDFDocument150 pagesDAMISCH, Hubert - The Origin of Perspective Part1 PDFThiago Ponce de Moraes100% (1)

- Kitsch and Art-Pennsylvania State University Press (2018)Document148 pagesKitsch and Art-Pennsylvania State University Press (2018)茱萸褚No ratings yet

- Fautrier PDFDocument23 pagesFautrier PDFJonathan ArmentorNo ratings yet

- Walter Benjamin - Paris of The Second Empire in BaudelaireDocument13 pagesWalter Benjamin - Paris of The Second Empire in BaudelaireBrent Smith-CasanuevaNo ratings yet

- Barthes Reality EffectDocument5 pagesBarthes Reality EffectBo-Won KeumNo ratings yet

- Panofsky, Iconography, and SemioticsDocument14 pagesPanofsky, Iconography, and SemioticsZhennya SlootskinNo ratings yet

- Quest For The Essence of Language (Jakobson)Document10 pagesQuest For The Essence of Language (Jakobson)alex33% (3)

- The Challenge of Bewilderment: Understanding and Representation in James, Conrad, and FordFrom EverandThe Challenge of Bewilderment: Understanding and Representation in James, Conrad, and FordNo ratings yet

- Marx After Marx: History and Time in the Expansion of CapitalismFrom EverandMarx After Marx: History and Time in the Expansion of CapitalismNo ratings yet

- Tradition and The Individual TalentDocument5 pagesTradition and The Individual TalentFrank HobbsNo ratings yet

- Concerning The "Mechanical Parts of Painting" and The Artistic Culture of 17th-Century France" by Donald PosnerDocument16 pagesConcerning The "Mechanical Parts of Painting" and The Artistic Culture of 17th-Century France" by Donald PosnerFrank Hobbs100% (1)

- Wolf Kahn: Early DrawingsDocument100 pagesWolf Kahn: Early DrawingsFrank Hobbs100% (4)

- Unknown CorotDocument108 pagesUnknown CorotFrank Hobbs100% (5)

- Observation and Invention: The Space of DesireDocument19 pagesObservation and Invention: The Space of DesireFrank Hobbs100% (2)

- Formal AnalysisDocument7 pagesFormal AnalysisFrank Hobbs100% (1)

- Two Ways of Seeing A RiverDocument2 pagesTwo Ways of Seeing A RiverFrank Hobbs100% (1)

- Matisse On ArtDocument1 pageMatisse On ArtFrank HobbsNo ratings yet

- Drawn To That MomentDocument3 pagesDrawn To That Momentdable_g100% (1)

- The Technical Aspects of Degas's ArtDocument26 pagesThe Technical Aspects of Degas's ArtFrank Hobbs100% (1)

- Stuart Shils - Between Earth & Sky, 2005Document1 pageStuart Shils - Between Earth & Sky, 2005Frank Hobbs100% (1)

- PhilipPearlstein On Stylistic CensorshipDocument7 pagesPhilipPearlstein On Stylistic CensorshipFrank HobbsNo ratings yet

- The Emergence of Tonal DrawingDocument9 pagesThe Emergence of Tonal DrawingFrank Hobbs100% (4)

- Learning From PoussinDocument10 pagesLearning From PoussinFrank Hobbs100% (1)

- Lesson 1 21stDocument42 pagesLesson 1 21stMaricar Francisco-ValenciaNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Literature Final Exam: Said The ToadDocument3 pagesIntroduction To Literature Final Exam: Said The ToadzikyungNo ratings yet

- Poetry Booklet RubricDocument2 pagesPoetry Booklet Rubricstefani61247213No ratings yet

- Common Core El A Informational Text Article CheetahDocument13 pagesCommon Core El A Informational Text Article CheetahIman MansourNo ratings yet

- Shri Raghavendra MangalAshTakamDocument12 pagesShri Raghavendra MangalAshTakamapi-26570247No ratings yet

- Presentation Rubric Social StudiesDocument1 pagePresentation Rubric Social StudiesmrhylandNo ratings yet

- My Practice 2Document42 pagesMy Practice 212210-158No ratings yet

- Ancient Promises by Jaishree MisraDocument34 pagesAncient Promises by Jaishree MisraChristy JohnsonNo ratings yet

- 28-Article Text-75-1-10-20210807Document13 pages28-Article Text-75-1-10-20210807Fahad AliNo ratings yet

- Literary History of Sanskrit Buddhism From Winternitz Sylvain Levi Huber by GK Nariman (1920)Document416 pagesLiterary History of Sanskrit Buddhism From Winternitz Sylvain Levi Huber by GK Nariman (1920)morefaya200650% (2)

- Industry Insider TV Contest Pilot Proposal Example How I Met Your MotherDocument3 pagesIndustry Insider TV Contest Pilot Proposal Example How I Met Your MotherMichael PetrieNo ratings yet

- John 1:14, Jesus "Full of Grace."Document8 pagesJohn 1:14, Jesus "Full of Grace."Lesriv Spencer100% (1)

- Examples of SynecdocheDocument2 pagesExamples of Synecdochekiratuz1998No ratings yet

- The American Esperanto Book - Arthur BakerDocument328 pagesThe American Esperanto Book - Arthur BakerPaulo Silas100% (2)

- Nugroho Syahputra - TOEFL Reading ExerciseDocument5 pagesNugroho Syahputra - TOEFL Reading ExerciseNET BINARYNo ratings yet

- Songs of TravelDocument3 pagesSongs of TravelWaldo RamirezNo ratings yet

- Historia Regum Britanniae Le Morte D'arthur: SdsdfsdfasdasdasdweqwesdfsdfdsfsdfDocument1 pageHistoria Regum Britanniae Le Morte D'arthur: SdsdfsdfasdasdasdweqwesdfsdfdsfsdfJay PaleroNo ratings yet

- Eco FeministDocument7 pagesEco FeministmiuasakuraNo ratings yet

- Critica de La Razon Andina Critique of ADocument11 pagesCritica de La Razon Andina Critique of AAlejandro Barrientos SalinasNo ratings yet

- Literary Devices in English: by Juan Carlos Gomez YancesDocument36 pagesLiterary Devices in English: by Juan Carlos Gomez YancesMa. Chhristina PrivadoNo ratings yet

- (British Literature in Context in The Long Eighteenth Century) Mona Narain, Karen Gevirtz - Gender and Space in British Literature, 1660-1820-Ashgate Pub Co (2014)Document252 pages(British Literature in Context in The Long Eighteenth Century) Mona Narain, Karen Gevirtz - Gender and Space in British Literature, 1660-1820-Ashgate Pub Co (2014)ciaradoloreNo ratings yet

- Taller Genetica Molecular # 3Document6 pagesTaller Genetica Molecular # 3Lina SánchezNo ratings yet

- Adobe Scan 20-Sep-2021Document6 pagesAdobe Scan 20-Sep-2021Daliya ChakrobortyNo ratings yet

- For ResearchDocument8 pagesFor ResearchAkashdeep RamnaneyNo ratings yet

- National Artists in Philippine LiteratureDocument17 pagesNational Artists in Philippine LiteratureJayson Paul Dalisay DatinguinooNo ratings yet

- LeisureDocument2 pagesLeisureShahzadRJNo ratings yet

- Romans Bible Study 19: Sonship in The Spirit - Romans 8:14-25Document5 pagesRomans Bible Study 19: Sonship in The Spirit - Romans 8:14-25Kevin MatthewsNo ratings yet