Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Reducing Human Error QP

Reducing Human Error QP

Uploaded by

cudalbgeo2005Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Reducing Human Error QP

Reducing Human Error QP

Uploaded by

cudalbgeo2005Copyright:

Available Formats

H E A LT H CA R E

Q UA L I T Y

Reduce Human Error

How to analyze near misses and sentinel events, determine root causes and implement corrective actions

by James J. Rooney, Lee N. Vanden Heuvel and Donald K. Lorenzo

HAT CAUSED THE last sentinel event (an unexpected occurrence involving death or serious physical or psychological injury) at your healthcare facility? The last quality of care problem? The last near miss? In most cases, human error is determined to be either the direct causea pharmacist incorrectly filling a medication order, or a nurse failing to respond to an IV alarmor a significant contributoran oxygen bottle running empty when the technician fails to notice it needs replacing. In many cases, if the human mistake results in only a minor quality of care problem, no follow-up action is necessary. However, if this human mistake results in a near miss or sentinel event, a report will be completed, and the responsible person might be coached, disciplined or maybe even fired. As a result, most managers and team leaders feel relatively confident the mistake will not occur again. However, experience shows us mistakes will likely recur.

Historically, human errors are significant factors in almost every quality problem, equipment shutdown or accident in industrial and manufacturing facilities. One study of refining and petrochemical plants identified the following causes of accidents: equipment and design failures, 41%; operator and maintenance errors, 41%; inadequate or improper procedures, 11%; inadequate or improper inspection, 5%; and miscellaneous causes, 2%.1 An adverse event in the healthcare field is defined as an injury caused by medical management rather than by the patients underlying disease or condition. 2 Not all, but a sizable number, of adverse events are the result of human error. A Harvard Medical Practice study examined more than 30,000 randomly selected discharges from 51 randomly selected hospitals in New York in 1984 (the most recent statistics available).3 Adverse events occurred in 3.7% of the hospitalizations. The proportion of adverse events attributable to errors was 58%, while the proportion due to negligence was 27.6%.

QU A L I T Y P R O G R E S S

S E P T E M B E R

2 0 0 2

27

REDUCE HUMAN ERROR

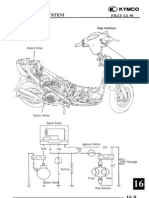

FIGURE 1

Random Variability

FIGURE 2

Systematic Variability

FIGURE 3

Sporadic Variability

8 9

10

8 9

10

8 9

10

Although most of these adverse events resulted in disability lasting less than six months, 13.6% resulted in death and 2.6% caused permanently disabling injuries. The most common adverse events were: Drug complications, 19%. Wound infections, 14%. Technical complications, 13%. Today, the challenge for healthcare management is to implement systems to reduce the frequency of human errors and devise ways to mitigate the consequences of the errors that do occur. Instead of blaming human error on ill trained or unmotivated workers, systems must be established to investigate and analyze near misses and sentinel events so root causes can be determined and corrective actions implemented. By doing this, healthcare teams should begin to experience significant improvements in overall system performance and safety.

wrong type of medication or administer the medication to the wrong patient. All these variations are inconsequential unless they cause an adverse impact on the quality of care, such as extended hospitalization, temporary or permanent injury to the patient or even death. In such cases, the variation would be considered a human error. Unfortunately, these limits of variability are usually not well-defined until a person makes a mistake that results in a problem big enough to warrant corrective action.

Human errors

Human errors are divided into two types: Unintentional errors: Actions committed or omitted with no prior thought. These errors, such as misreading a gage, bumping the wrong switch or forgetting to properly set the dose on an X-ray device, are usually thought of as accidents. Intentional errors: Actions deliberately committed or omitted because workers believe their actions are correct or better than the prescribed actions. For example, a physician might intentionally perform an erroneous action if the cause of a patients symptoms is misdiagnosed. Other intentional deviations include shortcuts that are not recognized as human errors until circumstances arise in which the actions exceed the system tolerances. To speed up the filling of an automated medication dispenser unit, for example, a pharmacy technician might not perform the verifications specified by the procedure. Remember, the important distinction between an intentional deviation and malevolent behavior is

Understanding human error

Opportunities for error exist in every task performed by a nurse, physician or any other healthcare employee. Even though a single task may never be performed exactly the same way twice, minor variations in performing a task are usually of no concern. However, when some limit of acceptability is exceeded, a variation is considered a human error. Human error is any human action or lack thereof that exceeds the tolerances defined by the system with which the human interacts. 4 For example, a nurse asked to administer a medication to a patient might administer too much or too little, administer the

28

S E P T E M B E R

2 0 0 2

W W W . A S Q . O R G

motive. An intentional deviation is not intended to harm the system, but its effect on the system may be undesirable. A malevolent act is not an errorit is a deliberate action intended to produce a harmful effect. The term human error in this article does not include malevolent acts.

TABLE 1

Internal Performance Shaping Factors

Emotional state Gender Physical condition/health Influences of family and other outside persons or agencies Group identifications Culture

Variability

Even though a nurse, doctor or instrument specialist may be well-trained and highly motivated, human errors are still a natural and inevitable result of the variability of human interaction with a system. There Source: A.D. Swain and H.E. Guttmann, Handbook of Human Reliability Analysis With Emphasis on are three types of variability. Knowing which one Nuclear Power Plant Applications (Washington, DC: U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission, 1985). occurs in a given case will help explain why errors happen and what can be done to control them. To understand these types of variability, think of a rifleman firing 10 shots at a target, and consider any shot off the target an error: Random variability: Characterized by a dispersion pattern centered around a desired normin this Although widespread agreement exists on the causes of prescripexample its the bulls-eye (see Figure tion drug errors, there is little consensus on the methods needed to 1). Personnel selection, training, address these problems. A new paper presented to congressional supervision and quality control prohealth policy staff by ASQ advocates the wider adoption of proven grams are all ways to control random quality methods in an effort to reduce medication errors. variability. Random errors occur As part of the Societys ongoing effort to cultivate contacts with when these programs are deficient, national policymakers in Washington, DC, ASQ officials met with the when tolerance limits are too tight or health policy advisor to Congressman Michael Bilirakis of Florida earwhen workers cannot control key lier this year. The advisor asked for suggestions from ASQ on ways performance factors. quality methods could be used to reduce prescription drug errors. Systematic variability: Characterized ASQ staff, with input from members of the Health Care Division by a dispersion pattern offset from a and the Food, Drug & Cosmetic Division, prepared a position paper desired norm (see Figure 2). Such titled Using Quality Methods To Reduce Prescription Drug Errors. errors are called systematic errors. It is available at www.asq.org/news/ These errors occur, for example, when interest/prescription.pdf. workers are given only one limit ASQ has also joined with the National instead of a lower and upper limit. In Patient Safety Foundation (NPSF) to form this case, they may deliberately try to an alliance that will offer solutions for be on the safe or unlimited side. reducing errors and increasing patient Biases can also exist in tools, equipsafety in healthcare delivery. The two ment, instructions or the worker s groups will collaborate to develop a toolpersonality, training or experience. box of products and services for leaders Telling workers how well they are of healthcare organizations and acute care settings to increase patient doing with respect to real goals will safety. ASQ-NPSF events will share successful case study implemenhelp reduce systematic errors. tation of the toolbox methods such as Six Sigma and distribute Sporadic variability: Characterized applicable patient safety solutions to various healthcare channels. by an occasional outlier, such as a For more information on the NPSF, go to www.npsf.org. tight cluster of shots with one shot substantially off the mark for reasons

Training/skill Practice/experience Knowledge of required performance standards Stress: mental or bodily tension Intelligence Motivation/work attitude Personality

ASQ Lends a Hand At Reducing Healthcare Errors

QU A L I T Y P R O G R E S S

S E P T E M B E R

2 0 0 2

29

REDUCE HUMAN ERROR

that are readily imaginable, such as a sudden distraction or an involuntary twitch (see Figure 3, p. 28). These errors are often not correctable by additional training or indoctrination because they

are not the result of inadequate knowledge or motivation. To reduce sporadic errors, we must categorize the errors and the conditions under which they occur in such a way that the errors can be related to controllable conditions.

TABLE 2

External Performance Shaping Factors

Task, equipment and procedural characteristics Procedures: written or not written Written or oral communications Cautions and warnings Work methods/practices Dynamic vs. step-by-step activities Team structure and communication Perceptual requirements Physical requirements: speed and strength Anticipatory requirements Interpretation/decision making Complexity: information load Long- and short-term memory load Calculational requirements Feedback: knowledge of results Hardware interface factors: design of control equipment, test equipment, process equipment, job aids or tools Control-display relationships Task criticality Frequency/repetitiveness

Performance shaping factors

Healthcare workers are an essential element of any healthcare system. To minimize human errors in medical activities, managers must ensure the healthcare worker/machine interface, including interactions with other workers and with the equipment and environment, is compatible with the capabilities, limitations and needs of the worker. A performance shaping factor (PSF) is anything that affects a workers performance of a task within the system. PSFs can be divided into three classes:5 Internal PSFs that act within an individual. External PSFs that act on an individual. Stressors. Internal PSFs are the individual skills, abilities, attitudes and other characteristics a worker brings to the job (see Table 1, p. 29). Some of these, such as training, can be improved by managers; others, such as a short-term emotional upset triggered by a family crisis, are beyond any practical management control. Table 2 lists external PSFs that influence the environment in which tasks are performed. External PSFs are divided into two groups: Situational characteristics: General PSFs that may affect many different jobs. Task, equipment and procedural characteristics: Related to a specific job or a specific task within a job. Job and task instructions are a particularly important part of the task characteristics because they have such a large effect on human performance. By emphasizing the importance of preparing and maintaining clear, accurate task instructions, managers can significantly reduce the likelihood of human errors.

Situational characteristics Architectural features Environment: temperature, humidity, air quality, lighting, noise, vibration or general cleanliness Work hours/work breaks Shift rotation Availability/adequacy of special equipment, tools or supplies Staffing levels Organizational structure: authority, responsibility or communication channels Actions by supervisors, co-workers or accreditation and regulatory personnel Facility policies

Source: A.D. Swain and H.E. Guttmann, Handbook of Human Reliability Analysis With Emphasis on Nuclear Power Plant Applications (Washington, DC: U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission, 1985).

TABLE 3

Psychological and Physiological Stressors

Physiological stressors Long duration of stress Fatigue Pain or discomfort Hunger or thirst Temperature extremes Radiation Exposure to diseases Vibration Movement constriction Movement repetition Lack of physical exercise Disruption of circadian rhythm

Psychological stressors Suddenness of onset High task speed Heavy task load High jeopardy risk Threats of failure or loss of job Monotonous, degrading or meaningless work Long, uneventful vigilance periods Conflicting motives about job performance Negative reinforcement Sensory deprivation Distractions: noise, glare or movement Inconsistent cueing Lack of rewards, recognition or benefits

Source: A.D. Swain and H.E. Guttmann, Handbook of Human Reliability Analysis With Emphasis on Nuclear Power Plant Applications (Washington, DC: U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission, 1985).

30

S E P T E M B E R

2 0 0 2

W W W . A S Q . O R G

Mismatches between internal and external PSFs result in disruptive stress that degrades job performance. If too little stimulation is present, a worker will not remain sufficiently alert or motivated to do a good job. For example, a pharmacy worker who repetitively fills medication orders may not be alert enough to notice a tablet was omitted. On the other hand, too much stimulation will quickly overburden a worker and degrade job performance. In such situations, workers tend to focus on the largest or most noticeable signals and ignore some information entirely, omit or delay some responses, process information incorrectly and reject information that conflicts with their diagnosis or decision, or mentally or physically withdraw. See Table 3 for some examples of disruptive psychological and physiological stressors. Although stress usually has a negative connotation, some stress is actually necessary for humans to function at optimum performance (see Figure 4, p. 32). Facilitative stress is anything that arouses us, alerts us, prods us to action, thrills us or makes us eager. When a positive balance exists between internal and external PSFs, workers experience facilitative stress and their job performance is at its best. Managers must recognize most PSFs, including many internal PSFs, are within their control. By designing work situations that are compatible with human needs, capabilities and limitations, carefully matching workers with job requirements, and rewarding positive behaviors, managers can create conditions that optimize worker performance and minimize human errors.

ASQ Facilitates Application Of ISO 9000 to Healthcare

By Michael Stoecklein, ASQs healthcare market development manager, and Mickey Christensen, Health Care Division standards committee chair

Since the publication of the Institute of Medicines 1999 report To Error Is Human: Building a Safer Health System, there has been increasing interest in trying to identify and use methods to help reduce errors and improve safety while simultaneously improving an organizations operating margin. Other industries have proven ISO 9000 is a very powerful quality management tool, and some healthcare service organizations have found it can help provide better healthcare systems and reduce the incidence of avoidable adverse events. ASQs Health Care Division and the Automotive Industry Action Group collaborated to develop ISO 9004:2000 based document guidelines for process improvements in health service organizations. ASQs Health Care Division helped lead the group effort in drafting the document. At an international workshop in 2001, attendees modified the draft, which was later accepted for publication by the International Organization for Standardization, known as ISO. After the workshop in Detroit, the attendees voted to publish the ISO IWA-1 document. The IWA-1 document can be used by healthcare organizations to implement an ISO 9000 quality based management system and make accreditation with other agencies easier, thereby minimizing the number of resources required to comply. IWA-1 contains much of the text of ISO 9004:2000 but also includes specific guidance for its implementation in the healthcare sector. The guidelines are voluntary and not intended for certification or accreditation. Copies of the IWA-1 document and the reports published by the Institute of Medicine are available from ASQ Quality Press, http://qualitypress.asq.org. ASQ has also developed a training course, IWA-1 Train the Trainer, and some training materials. The next course is scheduled for Sept. 23-26 in San Diego. Go to www.asq.org/ed/courses/descriptions/ iwahealthcare.html for more information. In addition, ASQ recently began hosting quality conversations on a variety of topics, the most recent being one about Six Sigma in healthcare. To read a copy of the transcript, go to www.asq.org/ ed/qconvs/062002sixsigmahc/index.html.

General approaches for reducing human error

When contemplating ways to improve human performance, managers must address two basic types of errors: Those whose primary causal factors

QU A L I T Y P R O G R E S S

S E P T E M B E R

2 0 0 2

31

REDUCE HUMAN ERROR

are individual human characteristics TABLE 4 When To Use a Self-Checking Technique unrelated to the work situation. Those whose primary causal factors 1. Are you unsure about the intent 6. Is this a routine or boring, are related to the design of the work but critical task? of the steps or the task or situation. performance standards? Employing appropriate hiring and job 2. Are you confused or do you sense 7. Can you clearly see and identify assignment policies is an important something is not right? the equipment you are working on? means for managers to reduce the causes of the first type of error. But, on any given 8. Do you have insufficient indication 3. Has the task been interrupted, of system or component status? causing you to begin the task day, a worker could be emotionally upset again, or is it a departure from a or fatigued and commit an error even well-established routine? though human factors specialists estimate 9. Have you had an unexpected 4. Have you received verbal instruconly 15 to 20% of workplace errors are tions on performing the task? encounter with a system, system interlock or system alarm? primarily caused by such internal human 6 conditions. 5. Are you hurried or performing 10. Are you fatigued? several tasks simultaneously? The majority, 80 to 85%, of human errors result from the design of the work situation, such as the tasks, equipment Here are two examples that can serve as a starting and environment.7 Managers can directly point in identifying error likely situations in your own control these factors. A work situation where the PSFs healthcare facility: are not compatible with the capabilities, limitations or 1. A 6-year-old boy died after undergoing a magnetic needs of an employee is called an error likely situaresonance imaging (MRI) exam when the tion. In a sense, an error likely situation is one in machines powerful magnetic field jerked a metal which a person has unintentionally been set up to oxygen tank across the room and crushed the make a mistake. Error likely situations can result from childs head. The force of the devices 10-ton maga variety of causes: net is about 30,000 times as powerful as the Earths Deficient procedures. magnetic field, and 200 times stronger than a com Poor communication between workers. mon refrigerator magnet. Inadequately trained workers. 2. A bar coding system was implemented for the Conflicting interests of workers. administration of medications. When the system Inadequately labeled equipment. was designed, the display units were intended to be Poorly designed equipment. used at the patients bedside. However, the batteries in the units run down so quickly the staff ends up leaving them plugged in FIGURE 4 Facilitative Stress in the hallway. Now the nurses cannot see Task load or hear the terminal indications when they Very administer medications to patients. low Optimum Heavy High By providing the resources necessary to identify and eliminate error likely situations, managers can improve the PSFs and dramatThreat ically reduce the frequency of human errors. stress This strategy is called the work situation approach and involves the five elements described below. To maximize the benefits of such a strategy, managers should solicit healthcare workLow Very Optimum Moderately Extremely ers input into this strategy at every low high high opportunity. After all, the workers can best Stress level identify the factors that hinder their perforPerformance effectiveness

32

S E P T E M B E R

2 0 0 2

W W W . A S Q . O R G

mance and will likely support such a strategy if they are not penalized for telling the truth.

Element 1: Implement good human factors engineering

Human factors engineering and ergonomics are concerned with In response to a serious problem, the Leapfrog Group, a coalition of ways to design jobs, machines, opermore than 100 public and private organizations that provide healthcare ations and work environments so benefits, is taking action. The group was created to help save lives and they are compatible with human reduce preventable medical mistakes. It mobilizes employer purchascapacities and limitations. Many ing power to initiate breakthrough improvements in healthcare safety human errors in healthcare are and gives consumers information to make more informed hospital caused by equipment and work choices. environments that were not initially This voluntary program is aimed at getting large purchasers to alert designed with an emphasis on mainthe healthcare industry that big leaps in patient safety and customer tainability and human factors engivalue will be recognized and rewarded with preferential use and other neering principles. Maintainability is intensified market reinforcements. The Leapfrog Group was founded the probability a piece of equipment by the Business Roundtable, a national associawill be restored to specified condition of Fortune 500 CEOs. tions within a given period after Hospitals are already taking important steps maintenance is performed in accorto ensure patients safety. Based on overdance with prescribed procedures whelming scientific evidence, the Leapfrog and resources. Group decided to focus on three practices that A new system design should have tremendous potential to save lives: account for all necessary mainte Computerized physician order entry. nance behaviors through proper Evidence based hospital referral. labeling; accessibility for repair, ICU physician staffing. removal and replacement; proper While these steps will not prevent all mistakes in hospitals, they are inspection and testing; and availa vital first effort. For more information on the Leapfrog Group and ability of spare parts and tools. these practices, visit www.leapfroggroup.org. Some examples include knobs that can be grasped and turned with reasonable force, labels that can be potential error likely situations. Having these read from a reasonable distance and critical or unique resources available during design reviews has other tools permanently located at the job site. advantages, too. It helps: Identification and elimination of error likely situa Provide a cost effective and practical way to resolve tions early in the system design phase are obviously the identified problem areas. more desirable than the frustrating and costly task of Provide an excellent opportunity for training on the retrofitting. Because most system designs are based on new process. a similar system currently in service, it would be pru Develop a sense of ownership of the new process dent to evaluate the existing system to help determine among workers. future requirements. Reviewing old drawings, performing walkElement 2: Provide clear, accurate procedures and instructions throughs and interviewing physicians and nurses are Many human errors in healthcare can be prevented worthwhile ways to evaluate an existing system. by ensuring clear, accurate procedures and job aids are Including these personnel in design reviews or as peravailable and used by all workers. This will help manent members of the design team are good ways to reduce workers reliance on skill and memory to perinvolve the users of the new process and draw on form a task, assist workers in decision making and their knowledge and experience to help identify

QU A L I T Y P R O G R E S S

Leapfrog Group Forms Coalition To Improve Patient Safety

S E P T E M B E R

2 0 0 2

33

REDUCE HUMAN ERROR

FIGURE 5

Conversion of Knowledge to Skill

End of initial training and practice

High

With practice of simulated upsets

With no further practice

Low Time Vertical arrows represent practice sessions such as drills, talk-throughs, what-if challenges and simulator training. Response skills

criticality of the task, but it is important to include warnings, cautions and other critical parameters for workers at all levels of expertise. Use language understandable to the worker to reduce the potential for errors, especially in stressful situations. Procedures can be made more understandable if you include only one action in each procedure step and use short but complete language, active voice, simple sentences and positive phrases. Besides being well-written, procedures and job aids must be readily available to workers. Ideally, the procedures should be located where they will be used. For example, the directions on how to use an autoclave to clean surgical instruments should be located on the front of the machine. If thats not possible, a single set of procedures should be kept in a centrally located place.

help ensure a given task is performed consistently. Written procedures provide step by step directions describing how and when to perform portions of the task. Job aids such as flowcharts, decision tables and checklists can be used to concisely organize information needed to perform problem diagnosis and aid workers who are performing tasks involving numerous steps. You can increase a procedure or job aids effectiveness by incorporating these key principles: Select a procedure style or format that is usable, familiar and best communicates the information to the worker. Ensure the procedure is accurate and complete to maintain credibility and guarantee continued use. If procedures contradict the way tasks are performed in practice, workers will soon lose faith in the procedures and will not use them. Involving experienced workers in procedure development and establishing a proper frequency for updating procedures will help create and maintain accurate procedures. To further ensure procedures remain accurate, experienced workers should conduct a periodic review. Include the appropriate level of detail in each procedure. Too little detail will make the procedure unusable by the inexperienced worker, and too much detail may discourage the experienced worker from using it. The appropriate level of detail will be determined by the level of worker expertise and the

34

Element 3: Provide job relevant training and practice

Training ensures healthcare workers possess the basic skills necessary to effectively perform their functions. Several types of training have proven most effective in reducing human errors, including initial skill training, refresher training and management systems training. Initial skill training is generally conducted in the classroom and supplemented with on-the-job experience. It prepares workers for experiences they will routinely encounter and those they will infrequently encounter. If training does not include the infrequent events or situations, the likelihood of successfully handling such situations will depend solely on the problem solving and decision making skills of the worker. In addition to initial training, refresher training on nonroutine or modified tasks will minimize worker errors and reduce the potential for a workers skills to deteriorate. A refresher training program is needed to assist workers in developing and maintaining a high skill level. Such a program will address a workers loss of skills and enhance skills beyond the initial training level. The sawtooth curve in Figure 5 presents the potential benefits of a refresher training program on worker responses vs. performing only initial training. The curve illustrates the conversion of knowledge to skill through repeated training and practice.

S E P T E M B E R

2 0 0 2

W W W . A S Q . O R G

To round out a healthcare training program, management system training is required on a regular basis to ensure healthcare workers can readily identify and follow relevant management systems. For example, on many safety critical systems, a management system exists to help prevent systematic human variability. To prevent a common cause human error, many hospitals have policies for redundant checking of medication and treatments. Many of these systems are in place to prevent human errors and should not be overlooked when developing a healthcare training program.

Element 4: Provide ways to detect and correct human errors

Many human errors in healthcare can be prevented by implementing certain administrative controls and systems. For instance, some companies have policies that require healthcare workers to work in pairs for certain activities. This buddy system can be effective in detecting a human error before an undesired consequence occurs. For example, after an X-ray technician finishes work on a patient, the X-rays can be viewed to verify the work was satisfactory. Healthcare workers should identify opportunities to proof their work to detect mistakes before patients are returned to their rooms and the equipment is returned to service. Whenever possible, these proofs should be incorporated into written procedures to help guarantee they are performed and to provide training for new employees. Another way healthcare workers can detect and correct human error is by using self-checking techniques. A self-checking technique is a practice in which a person consciously and deliberately reviews the intended action and expected response before performing a task. One technique is the five rights used to administer medications: Right patient. Right medication. Right dose. Right route. Right time.

vate workers to improve their levels of performance. A motivated workforce with a positive attitude is less likely to commit errors; therefore, a healthcare team leader or supervisor should introduce various motivational factors into the work situation: Recognize achievement. Praise a technician in the presence of his peers. Provide access to information. Train a nurses aide to obtain information on a computer system normally used only by the nurses. Allow use of ones ability. Allow a physician who is familiar with computers to provide input into the selection of the hardware and software for the new computerized healthcare management system. Give challenging assignments. Give the central stores staff the opportunity to help determine the optimum distribution of medical gas bottles to units in the hospital. Assign extended responsibilities. Allow a clerk who has shown both the interest and the ability to move into a healthcare position. Provide the freedom to act. Empower a technician to requisition a new testing instrument without prior approval from his or her immediate supervisor. Seek involvement in planning, problem solving or goal setting. Invite healthcare workers to participate in quality of care investigations, healthcare budget forecasting or goal setting.

Improve overall system performance

Many times, human errors are the result of error likely situations that come about due to the way the procedures are written, the training is conducted, or the systems are designed, operated or maintained. Todays management is challenged by a paradigm shift from blaming mistakes on carelessness and incompetence to implementing methods to identify the root cause of why a person makes a mistake. Allocating time and resources to understanding human factors, and identifying and eliminating error likely situations through methods such as the work situation approach, will significantly help improve overall system performance and process safety.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank Myron Casada, Vernon Guthrie, Maureen Hafford, Leslie Adair and Angie Nicely for their assistance with this article.

Element 5: Help workers achieve their social and psychological needs

Worker motivation will likely be high if management applies accepted human factors principles to job tasks, training provides the necessary skills to handle all contingencies and workers are actively involved in their jobs through participation strategies. In addition, many first-line healthcare managers are given the opportunity to shape the work environment and moti-

REFERENCES

1. R.E. Butikofer, Safety Digest of Lessons Learned

QU A L I T Y P R O G R E S S

S E P T E M B E R

2 0 0 2

35

REDUCE HUMAN ERROR

(Washington, DC: American Petroleum Institute, 1986). 2. T.A. Brennan, Incidence of Adverse Events and Negligence in Hospitalized Patients: Results of the Harvard Medical Practice Study I, New England Journal of Medicine, Vol. 324, No. 6. 3. L.L. Leape, The Nature of Adverse Events in Hospitalized Patients: Results of the Harvard Medical Practice Study II, New England Journal of Medicine, Vol. 324, No. 6.

4. D.K. Lorenzo, A Managers Guide to Reducing Human Errors: Improving Human Performance in the Chemical Industry (Washington, DC: American Chemistry Council, 1990). 5. A.D. Swain and H.E. Guttmann, Handbook of Human Reliability Analysis with Emphasis on Nuclear Power Plant Applications (Washington, DC: U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission, 1985). 6. A.D. Swain, Design Techniques for Improving Human Performance in Production (Albuquerque, NM: Industrial and Commercial Techniques, 1986). 7. Ibid.

JAMES J. ROONEY is a senior risk and

reliability engineer with ABS Consultings risk consulting division in Knoxville, TN. He earned a masters degree in nuclear engineering from the University of Tennessee. Rooney is a Fellow of ASQ and an ASQ certified quality auditor, quality auditor-HACCP, quality engineer, quality improvement associate, quality manager and reliability engineer.

LEE N. VANDEN HEUVEL is a senior risk and reliability engineer with ABS Consultings risk consulting division in Knoxville, TN. He earned a masters degree in nuclear engineering from the University of Wisconsin. Vanden Heuvel co-authored the Root Cause Analysis Handbook. DONALD K. LORENZO is a senior risk and

reliability engineer with ABS Consultings risk consulting division in Knoxville, TN. He earned a masters degree in nuclear engineering from the Georgia Institute of Technology. He authored A Manager s Guide to Reducing Human Errors: Improving Human Performance in the Chemical Industry and is director of the Process Safety Institute. QP

IF YOU WOULD LIKE to comment on this article, please post your remarks on the Quality Progress Discussion Board at www.asqnet.org, or e-mail them to editor@asq.org.

36

S E P T E M B E R

2 0 0 2

W W W . A S Q . O R G

You might also like

- Task 2 - RCA and FMEADocument8 pagesTask 2 - RCA and FMEAJeslin MattathilNo ratings yet

- STFFD-P1-004003-P05-0001 Rev C FAT Procedure For Complete SkidDocument50 pagesSTFFD-P1-004003-P05-0001 Rev C FAT Procedure For Complete SkidTuyen Pham100% (2)

- Introduction - JackyDocument35 pagesIntroduction - JackyJackylou B Tuballes RrtNo ratings yet

- Continuous Quality Improvements and SafetyDocument3 pagesContinuous Quality Improvements and Safetyapi-518020510No ratings yet

- Pubmed Healthwork SetDocument1,912 pagesPubmed Healthwork SetRazak AbdullahNo ratings yet

- To Err Is Human 1999 Report Brief PDFDocument8 pagesTo Err Is Human 1999 Report Brief PDFRenan LelesNo ratings yet

- FMT001 Prevention of Medical ErrorsDocument43 pagesFMT001 Prevention of Medical ErrorsgailgonesouthNo ratings yet

- Root Cause AnalysisDocument2 pagesRoot Cause Analysisjjjj000No ratings yet

- Patient Safety ModuleDocument49 pagesPatient Safety ModuleChinoNo ratings yet

- Medical Errors Definitions Causes PreventionDocument9 pagesMedical Errors Definitions Causes PreventionAmal SaeedNo ratings yet

- The Nurse's Role in Medication SafetyDocument6 pagesThe Nurse's Role in Medication Safetyloker ihc100% (1)

- The Safety and Quality of Health Care: David W. BatesDocument6 pagesThe Safety and Quality of Health Care: David W. Batesmike_helplineNo ratings yet

- Medical Errors Prevention and SafetyDocument15 pagesMedical Errors Prevention and SafetyXavior Sebastian FernandezNo ratings yet

- Fred IndividualDocument3 pagesFred IndividualsavneetkaurrattanNo ratings yet

- Error AnalysisDocument10 pagesError AnalysisjdmaneNo ratings yet

- To Err Is Human 1999 Report Brief PDFDocument8 pagesTo Err Is Human 1999 Report Brief PDFAjib A. Azis100% (3)

- 15 QsDocument4 pages15 Qsujangketul62No ratings yet

- Journal Reading On PharmacologyDocument2 pagesJournal Reading On Pharmacology284tzk2r9vNo ratings yet

- Medical Error Reduction and PreventionDocument26 pagesMedical Error Reduction and Preventionsura.alnahar95No ratings yet

- Medication ErrorDocument7 pagesMedication ErrorLenny SucalditoNo ratings yet

- Medical Errors-Causes Consequences Emotional ResponseDocument11 pagesMedical Errors-Causes Consequences Emotional ResponseAndreea MacsimNo ratings yet

- ID Tinjauan Yuridis Terhadap Malpraktik Yang Dilakukan Oleh Perawat Pada Rumah SakiDocument7 pagesID Tinjauan Yuridis Terhadap Malpraktik Yang Dilakukan Oleh Perawat Pada Rumah Sakialimu alamsyahNo ratings yet

- Medication Error ThesisDocument6 pagesMedication Error Thesisoaehviiig100% (2)

- Nursing: Student Name Affiliation Course Instructor Due DateDocument8 pagesNursing: Student Name Affiliation Course Instructor Due DateHAMMADHRNo ratings yet

- RoilsDocument4 pagesRoilsapi-568855135No ratings yet

- Medication ErrorsDocument7 pagesMedication Errorsapi-679663498No ratings yet

- Diagnostic Error in Internal Medicine PDFDocument12 pagesDiagnostic Error in Internal Medicine PDFemilio9fernandez9gatNo ratings yet

- Roils PaperDocument4 pagesRoils Paperapi-633434674No ratings yet

- 6 Understanding and Managing Clinical RiskDocument4 pages6 Understanding and Managing Clinical Riskanojan100% (1)

- Sept 13 Journalreview 2 DocxDocument3 pagesSept 13 Journalreview 2 DocxHarold Mantaring LoNo ratings yet

- Understanding Decision Making in Critical CarelDocument13 pagesUnderstanding Decision Making in Critical CarelaksinuNo ratings yet

- Case Study 1Document10 pagesCase Study 1Hamza ZahidNo ratings yet

- Rca - Lauren HerrDocument5 pagesRca - Lauren Herrapi-520453750No ratings yet

- Thesis Medication ErrorsDocument7 pagesThesis Medication ErrorsMichele Thomas100% (2)

- Sources of Error in Epidemiological StudiesDocument30 pagesSources of Error in Epidemiological StudiesFebrian FaisalNo ratings yet

- Preventing Medication ErrorsDocument26 pagesPreventing Medication ErrorsmrkianzkyNo ratings yet

- Safety Issues: in Health Care SystemDocument31 pagesSafety Issues: in Health Care SystemHaifa Mohammadsali AndilingNo ratings yet

- Basic Principles of Patient Safety-Overview-Self-Study Module-2013 PDFDocument35 pagesBasic Principles of Patient Safety-Overview-Self-Study Module-2013 PDFfmta100% (1)

- Medication ErrorsDocument13 pagesMedication Errorsrozsheng100% (1)

- Gold Mine or Dumpster Dive A Closer Look at Adverse Event ReportsDocument4 pagesGold Mine or Dumpster Dive A Closer Look at Adverse Event ReportsAndrada ArmasuNo ratings yet

- Roils EssayDocument4 pagesRoils Essayapi-632682404No ratings yet

- Adverse Event: Wirsma Arif Harahap Surgical OncologistDocument49 pagesAdverse Event: Wirsma Arif Harahap Surgical OncologistAhmad Fakhrozi HelmiNo ratings yet

- Chapter 3Document28 pagesChapter 3SISNo ratings yet

- The Slim Book of Health Pearls: The Prevention of Medical ErrorsFrom EverandThe Slim Book of Health Pearls: The Prevention of Medical ErrorsNo ratings yet

- Enseñanza AnestesioDocument14 pagesEnseñanza AnestesioRaúl MartínezNo ratings yet

- Adverse Event or Near-Miss Analysis (Nursing) .EditedDocument10 pagesAdverse Event or Near-Miss Analysis (Nursing) .EditedMaina PeterNo ratings yet

- The COAT & Review Approach: How to recognise and manage unwell patientsFrom EverandThe COAT & Review Approach: How to recognise and manage unwell patientsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Legal Profession Paper - Medication ErrorDocument7 pagesLegal Profession Paper - Medication ErrorJayson TrajanoNo ratings yet

- NEUK 1464 (Revised) 1 (Updated)Document21 pagesNEUK 1464 (Revised) 1 (Updated)Sameen ShafaatNo ratings yet

- Medication Administration Risk AssessmentDocument7 pagesMedication Administration Risk AssessmentEdwin J OcasioNo ratings yet

- Man 238Document10 pagesMan 238Ujjwal MaharjanNo ratings yet

- Medical Errors - I: The Problem: G. Swaminath, R. RaguramDocument3 pagesMedical Errors - I: The Problem: G. Swaminath, R. RaguramAni RahimNo ratings yet

- Adverse Drug ReactionDocument4 pagesAdverse Drug Reactionapi-246003035No ratings yet

- Relationship BetweenvolemwDocument6 pagesRelationship Betweenvolemwcandra wNo ratings yet

- MED Medical-Incident-Reporting Treasury Incident-Policy en 2013Document7 pagesMED Medical-Incident-Reporting Treasury Incident-Policy en 2013Shafis KhanNo ratings yet

- Answers and Rationales For NCLEX Style Review QuestionsDocument12 pagesAnswers and Rationales For NCLEX Style Review QuestionsJacinth Florido Fedelin50% (2)

- Medication Error Research PaperDocument5 pagesMedication Error Research Paperafeaoebid100% (3)

- Literature Review Medication Safety in AustraliaDocument5 pagesLiterature Review Medication Safety in Australiaea7gpeqm100% (1)

- Medication ErrorsDocument8 pagesMedication ErrorsFarmisa MannanNo ratings yet

- Capacity CalculationDocument13 pagesCapacity CalculationPradeepNo ratings yet

- JITfinalDocument32 pagesJITfinalPradeepNo ratings yet

- Thread Scheduling and DispatchingDocument75 pagesThread Scheduling and DispatchingPradeepNo ratings yet

- Conditional RegressionDocument7 pagesConditional RegressionPradeepNo ratings yet

- S Tatistical Tolerance Synthesis Using Distribution Function ZonesDocument12 pagesS Tatistical Tolerance Synthesis Using Distribution Function ZonesPradeepNo ratings yet

- Logistic Regression: Multivariate AnalysisDocument29 pagesLogistic Regression: Multivariate AnalysisPradeepNo ratings yet

- Lecture 4Document45 pagesLecture 4PradeepNo ratings yet

- Regression With Categorical VariablesDocument28 pagesRegression With Categorical VariablesPradeepNo ratings yet

- Catogarical Data TestsDocument12 pagesCatogarical Data TestsPradeepNo ratings yet

- Main Overview of The Quality ProblemDocument45 pagesMain Overview of The Quality ProblemPradeepNo ratings yet

- INFORMS Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve and Extend Access To Operations ResearchDocument24 pagesINFORMS Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve and Extend Access To Operations ResearchPradeepNo ratings yet

- APICS CPIM Primary References 2009 ECODocument1 pageAPICS CPIM Primary References 2009 ECOPradeepNo ratings yet

- Building Good Models Is Not Enough: Richard RichelsDocument8 pagesBuilding Good Models Is Not Enough: Richard RichelsPradeepNo ratings yet

- Sampling Distributions and Forward InferenceDocument7 pagesSampling Distributions and Forward InferencePradeepNo ratings yet

- Attachemnt A - Body and Wheelchair MeasurementDocument2 pagesAttachemnt A - Body and Wheelchair MeasurementNur Adila MokhtarNo ratings yet

- Nanoscience and Nanotechnology in ArgentinaDocument84 pagesNanoscience and Nanotechnology in ArgentinaMaterials Research InstituteNo ratings yet

- SVM and Linear Regression Interview Questions 1gwndpDocument23 pagesSVM and Linear Regression Interview Questions 1gwndpASHISH KUMAR MAJHINo ratings yet

- Bukh DV 36 SmeDocument5 pagesBukh DV 36 SmeTullio OpattiNo ratings yet

- 302-1006-003 Make-Up750ml MEK-United States - ADITIVO PDFDocument8 pages302-1006-003 Make-Up750ml MEK-United States - ADITIVO PDFAlexander MamaniNo ratings yet

- Inverter Heat Pumps: Heat Pumps For Private and Public Swimming PoolsDocument4 pagesInverter Heat Pumps: Heat Pumps For Private and Public Swimming PoolsAinars VizulisNo ratings yet

- Annexure-9 SPL AI & ML-3Document13 pagesAnnexure-9 SPL AI & ML-3satyam sharmaNo ratings yet

- Introduction To RoboticsDocument14 pagesIntroduction To RoboticsmeneboyNo ratings yet

- Foundation of GuidanceDocument17 pagesFoundation of GuidanceFroilan FerrerNo ratings yet

- FDS - Unit 3 - MCQDocument8 pagesFDS - Unit 3 - MCQFatherNo ratings yet

- Organise 96Document70 pagesOrganise 96RamjamNo ratings yet

- Reading Comprehension Workshop 2 Texts For English IDocument2 pagesReading Comprehension Workshop 2 Texts For English IPROFESORAGURTONo ratings yet

- Action of Catalase On Hydrogen PeroxideDocument4 pagesAction of Catalase On Hydrogen PeroxideRuchie Ann Pono BaraquilNo ratings yet

- Bridge 3 Deck DesignDocument16 pagesBridge 3 Deck DesignMd MamroseNo ratings yet

- CH 1. Structure of Atom (Chem +1)Document80 pagesCH 1. Structure of Atom (Chem +1)Rehan AnjashahNo ratings yet

- Africa in American Media:: A Content Analysis of Magazine's Portrayal of Africa, 1988-2006 By: Stella Maris KunihiraDocument11 pagesAfrica in American Media:: A Content Analysis of Magazine's Portrayal of Africa, 1988-2006 By: Stella Maris KunihiraEthanNo ratings yet

- Event Report Insights Into HackathonDocument7 pagesEvent Report Insights Into HackathonSujoy SarkarNo ratings yet

- Hrm-340.3 Final Report Team-Six-SensesDocument23 pagesHrm-340.3 Final Report Team-Six-SensesFarisa Tazree Ahmed 1912999630No ratings yet

- Datasheet M-410iB-700 PDFDocument1 pageDatasheet M-410iB-700 PDFDiego Alejandro Gallardo IbarraNo ratings yet

- (Gender and Well-Being.) Ortiz, Teresa - Santesmases, María Jesús - Gendered Drugs and Medicine - Historical and Socio-Cultural Perspectives-Ashgate Publishing Limited (2014)Document261 pages(Gender and Well-Being.) Ortiz, Teresa - Santesmases, María Jesús - Gendered Drugs and Medicine - Historical and Socio-Cultural Perspectives-Ashgate Publishing Limited (2014)Federico AnticapitalistaNo ratings yet

- F50LX Cap 16 (Imp Avviamento)Document6 pagesF50LX Cap 16 (Imp Avviamento)pivarszkinorbertNo ratings yet

- ECCE WritingDocument22 pagesECCE Writinggesu piero lopez mejiaNo ratings yet

- Review Article Barium HexaferriteDocument11 pagesReview Article Barium HexaferriteIngrid Bena RiaNo ratings yet

- 14-Nm Finfet Technology For Analog and RF ApplicationsDocument7 pages14-Nm Finfet Technology For Analog and RF ApplicationsTwinkle BhardwajNo ratings yet

- Performance Combined With: Ultimate Control PossibilitiesDocument15 pagesPerformance Combined With: Ultimate Control PossibilitiesCậu BáuNo ratings yet

- GM Repertoire 1A The Catalan PDFDocument794 pagesGM Repertoire 1A The Catalan PDFYoSoyDavidNo ratings yet

- SuperchargerDocument14 pagesSuperchargerRangappa swamyNo ratings yet

- Manual Panacom ParlanteDocument20 pagesManual Panacom Parlanteagustina fernandezNo ratings yet

- Ultraspund in Pediatric EmergencyDocument22 pagesUltraspund in Pediatric EmergencyAli Akbar RahmaniNo ratings yet