Professional Documents

Culture Documents

William Morris: Early Influences

Uploaded by

Florence Margaret PaiseyCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

William Morris: Early Influences

Uploaded by

Florence Margaret PaiseyCopyright:

Available Formats

1 Florence Margaret Paisey Not by Bread Alone There needs to-day to be a protest made by some one against the

mechanical character of our decoration writes Clarence Cook in 1881, ...our homes are overrun with things, encumbered by useless ugliness... Such statements could easily be attributed to William Morris. And, though expressed by Cook, they almost certainly came out of Morris ideology and cultural influence. Further along, Cook states, ...I have reached a point where simplicity seems a good part of beauty, and utility only beauty in a mask... (Cook 283). Morris legacy is unmistakable. During the late 19th century, when Cook was writing for Scribners Monthly, Morris delivered five lectures on art, Hopes and Fears for Art. One lecture, The Beauty of Life, related his golden rule remove all superfluities in the home. Have nothing in your houses that you do not know to be useful, or believe to be beautiful (Morris 108). Morris philosophy of art and civilized life emphasized the unity of art and beauty; he felt both were necessary and integral to natural order. The beauty of life is a thing of no moment, he writes. And continues: ...for that beauty which is meant by ART, using the word in its widest sense, is, I contend, no mere accident to human life, which people can take or leave as they choose, but a positive necessity of life, if we are to live as nature meant us to; that is, unless we are content to be less than men (Hope 77). In Democracy of Art, Morris called for simplicity and the absence of encumbering gewgaws (Hope 110). He viewed industrialism and avaricious capitalism as both symptoms and causes of the perverse effects of machines the division of labor and

2 mechanization of crafts, resulting in shoddy goods and useless, tawdry bric-a-brac. Morris believed that manufacturers interests served only tyrannical and exploitative commercial purposes, decimating urban centers and perpetuating inhumane factory conditions. In Morris newspaper article, How I Became a Socialist, Morris stated, What shall I say concerning [modern civilizations] mastery of and its waste of mechanical power, its commonwealth so poor, its enemies of the commonwealth so rich, its stupendous organisation for the misery of life (Morris How 2). Unlike many artists and social reformers of Victorian England, Morris experienced no hardship from birth, he enjoyed privilege born of an affluent family, security and shelter. Born at Elm House in Waltham-stow, England in 1834, Morris was the oldest son of William and Emma Morris. Morris father, a reputable bill broker in the City of London, successfully speculated in a copper-mining project during the 1840s. This financial windfall brought the family unusual prosperity and formed the basis for William Morris substantial inheritance, privilege and protection from hardships and economic uncertainties of life. As a boy, Morris relished the idyllic countryside that surrounded the family residence, Woodford Hall, a grand Georgian manor house. A voracious reader with a romantic sensibility, Sir Walter Scotts novels and romantic adventures captivated his fancy. His youthful riding through Epping Forest shaped fertile experiences in which young Morris could play imaginative, adventuresome scenes while also visiting historic Essex churches and other neighboring, ancient buildings. Such activities, informally experienced, would deepen Morris inborn, free-spirited nature and profoundly sensitize him to chivalry, historic romance, ancient architecture, wildlife and the intricate, fluid patterns of organic

3 forms. By the time Morris entered formal schooling, he was nine. His sensibilities and proclivities had already taken root and the nearby prep school offered little to structure an idiosyncratic unsystematic education. He was soon sent to Marlborough College, following the premature death of his father, and he unhappily boarded there for several years before going up to Exeter College, Oxford. Still, while at Marlborough, Morris took comfort in voracious reading, riding the surrounding countryside, and, once again, observing ancient buildings, memorials and their architecture. Exeter College marked significant transitions in Morris life. First, within a few days, Morris met his lifelong friend and collaborator, Edward Burne-Jones. Both were at Exeter College and, although from very different backgrounds, both shared a similar idealism, knowledge base and enthusiasm for learning. Burne-Jones introduced Morris to his friends at Pembroke College, Oxford, and the group immediately formed a bond through their love of literature and chivalry this group became known as The Brotherhood. They read aloud and enjoyed all forms of literature by established authors such as Keats, Shelley, Tennyson, Milton and Shakespeare. Importantly, they also read papers of contemporary reformers such as Carlyle and Ruskin. These papers gave Morris his first awareness of the deep social divisions engendered primarily by poverty and destitution. Morris and Burne-Jones continued reading Ruskin avidly. Ruskins Stones of Venice and On the Nature of the Gothic as well as The Seven Lamps of Architecture impressed Morris deeply. These essays set forth an aesthetic philosophy based on harmonious forms that reflect the ethos, feeling and ethics of society. Ruskin believed that great art engages the whole of the human soul and compasses and calls

4 forth the entire human spirit (Ruskin Modern IV 42). Throughout Ruskins writings on art, he emphasizes that the greatness of a work (a painting) lies in its capacity to appeal to a spectators higher faculties and then the extent to which that work engages those higher faculties. In this one gets a sense of the relationship Ruskin saw between art and religion or morality art and religion both signify (higher) feelings of love, reverence, and dread whereby the mind is affected by its spiritual being. This relationship between feeling and art also characterizes Morris. Ruskin did not advocate specific religious commitments, however he questioned the merit of any art that would alter ones feelings of the religious feelings of love, reverence for the divine or perfection. He associated morality with culture and conduct the ethos or propriety prescribed by a culture. For Ruskin art takes an active role in a cultures moral discourse. Clearly, Ruskin profoundly influenced Morris, as did Oxford. Late in life, Morris letter to the Pall Mall Gazette titled, Magdalen Bridge can leave no doubt as to Morris continued love of this ancient, medieval city and the recognition of its character and profound effect on him. In protest to the suggestion that the University destroy its iconic Magdalen Bridge, rather than repair and preserve it, Morris wrote: It may well be thought that the mere words, `the destruction of Magdalen Bridge' would go at once to the heart of any one who knows Oxford well; that any one who has lived there either as gownsman or townsman, & who does not want to be set down as dull to any impression of art or history, would be eager to protest against such a strange piece of barbarism... (Morris Magdalen 1881). Clearly, Morris attachment to this city, its history and its architecture carried deeply

5 personal concerns. He absorbed the sense of its dignity, its societal place and, as would be expected, its architecture. Toward the end of his studies at Oxford, Morris and Burne-Jones traveled through France, roaming the French countryside as Morris had done as a youth in England. They visited ancient French churches and cathedrals, again, as Morris had done as a youth. Such experiences rekindled Morris early fascination with medievalism, architecture, landscape and untamed woods. These travels enabled him to study medieval painting, sculpture, tapestries and other ornamentation again, no doubt, recalling his early encounters and his deep-seated feeling for nature, the heroic and graceful, idealized forms. An excerpt from his poem, The Hall and the Wood published later in life illustrates this absorption with the countryside: Twas in the water-dwindling tide When July days were done, Sir Rafe of Greenhowes gan to ride In the earliest of the sun. He left the white-walled burg behind, He rode amidst the wheat, The westland-gotten wind blew kind Across the acres sweet. Morris roots, riding through the English countryside, aware of the seasons and rhythms of natural order, shine in each of his artistic undertakings. This is the unity in Morris -the distinctive imagery within all his texts architecture and furniture as well. An organic fluidity characterizes them. Morris was unique there is a progression of artistic forms based on his creations, there is emulation, but the artistic revolution he drove, has no rival. To this day, Morris designs and artistic tenets spring from those early, solitary years of heroic stories and resplendent woods.

6 However, there would be no William Morris architect, craftsman, printer, designer, artist and textile creator had he not taken a key career decision and changed. One wonders the extent to which Burne-Jones and members of The Brotherhood, bolstered him. Nonetheless, during a second tour of Northern France taking in the French countryside both Burne-Jones and Morris determined that their futures lie in art, not the Church Burne-Jones decided himself a painter and Morris, an architect. Although Morris finished studies for the Church at Oxford, he afterward pursued architecture, apprenticing to the Neo-Gothic architect, Edmund Street, in Oxford. The apprenticeship was difficult and not altogether successful. However, Streets idea of the architect as a complete artist concerned with all aspects of building glass, textile, woodwork, tapestry and furniture evidently made an impression on Morris. Previous to his apprenticeship with Street, Morris appreciated the artistry of tapestry and textiles, but expressed no inclination to design ornaments and dcor. Then, in Streets offices, Morris met the architect and craftsman, Phillip Webb. And, again, Morris found architect and craftsman together, however with Webb there was camaraderie. Another lifelong friend, influence and collaborator had arrived. This was a turbulent and probably troubled period in Morris life. The industrial revolution was at its peak and the effect of factories on the environment and architecture incensed him. According to Thompson, Morris disgust with the industrial revolution and capitalism, in general, had to do with the squalor and anarchy which he passed through in London and the great towns: from the degradation of its architecture and from the sham hypocrisy... (40). Morris, still sheltered and distant from impoverished laborers and their plight was affected more by the decay of buildings than exploitation and

7 inhumane conditions of life. However, Morris attitude and interest toward art and architecture came out of an understanding of social morality and, the author he read carefully, Ruskin, articulated this view. Morris acknowledged his debt to Ruskins emphasis on art as an expression of the whole moral being of the artist, and through him the quality of life of the society in which he lived (Thompson 33). Ruskins fervent writings on the relationship between art, the spirit and society together with Morris passion for architecture and landscape formed an aesthetic foundation that remained with Morris throughout his life. During this period, Morris also developed an interest in painting. And, when Ruskin wrote a defense of the Pre-Raphaelite approach, Morris noticed. He liked Pre-Raphaelite painters such as Rossetti, Holman Hunt and Millais. Their criticism toward academic art the rules, conventions, color and line suited him. Their preferred artistic themes of idealized nature and medieval heroic folktales delighted him. And, they too, followed Ruskin. Again, Morris had found kindred spirits. So, when Morris mentor, Street, moved his architectural offices to London, Morris followed, united with his valued friend, Burne-Jones. After meeting Rossetti, the Pre-Raphaelite visionary, Morris found an artistic home though, ultimately, a strange and complicated personal situation. These were birds of a feather Morris, Burne-Jones, Rossetti, Webb and the PreRaphaelite Brotherhood. Morris dye had been cast his early meanderings through the countryside, tales of heroic adventure and legend, sensitivity to form, function, material and building, disgust with mediocrity and hypocrisy, artistic vision and, then his own independent wealth worked to forge the creative artistry of a lifetime.

8 Morris was a man for all seasons. And like Sir Thomas More, he remained true to himself, his beliefs and his vision. Pevsner notes, Morris was the first artist to realize how precarious and decayed the social foundation of art had become during the centuries since the Renaissance, and especially during the years since the Industrial Revolution (Pevsner 15). In consequence, Morris turned to libertarian socialism a utopian society conceptualized as universal brotherhood and he idealized the art and architecture exemplified in medievalism. Given Morris keen observation and moral sensitivity, neither predilection is surprising. We know Morris through his multifaceted achievements and legacy in textiles, crafts, printing, architecture and design. Yet, it was his conscience and intelligence that shaped him, defined him and drove him. Morris consciousness emerged at a time when the West had industrialized production of crafts producing quantity available for the masses, but at the expense of inspired, creative design as previous ages had wrought. He turned to earlier periods of design for inspiration. The model of medieval guilds motivated him. From his perspective, they had supported refined craftsmanship where the craft embodies the artist and the artist the craft. They are one in the same there is gratification and worth in ones skill. The spirit inhabits ones work one lives not by bread alone. Morris opposed the mechanization of craft vehemently he detested cheap items manufactured with veneer and shoddy workmanship. And he stated, the division of labor, which has played so great a part in furthering competitive commerce, till it has become a machine with powers both reproductive and destructive... (Hope 122). This is Morris the craftsman, designer, humanitarian and social activist.

9 William Morriss legacy continues to influence culture in design, textiles, architecture, social standards and how we define and appreciate art. His graceful, yet punctilious designs encapsulate Ruskins and the Pre-Raphaelite precepts, articulating unity of art and nature. In essence, he understood beauty, idolized it and championed causes he felt would further it.

Works Cited Beckley, B. (Ed.). (1996). John Ruskin: Lectures on Art. New York: Allworth.

10 Bono, B. (1975). The Prose Fictions of William Morris: A Study in the Literary Aesthetic of a Victorian Social Reformer. Victorian Poetry, 13, 43-59. Clair, C. (1966). A History of Printing in England. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Cook, C. (1995). The House Beautiful: An Unabridged Reprint of the Classic Victorian Stylebook. New York: Dover. Drucker, J. (2006). Graphical Readings and the Visual Aesthetics of Textuality. Text, 16, 267-276. Eisenmann, S. E. (2002). Class Consciousness in the Design of William Morris. Journal of William Morris Studies, XV(1), 17-37. Harvey, C., Jon Press, and Mairi Maclean. (2011). William Morris, Cultural Leadership, and the Dynamics of Taste. Business History Review, 85(Summer), 245-271. doi: 10.1017/Sooo7680511000377 Maxwell, R. (Ed.). (2002). The Victorian Illustrated Book. Charlotte: University of Virginia. McGann, J. (1992). "A Thing to Mind"" The Materialist Aesthetic of William Morris. Huntington Library Quarterly, 55(1), 55-74. McGann, J. (2005). Culture and Technology: The Way We Live Now, What Is to Be Done? New Literary History, 36(1), 71-82. Morris, W. (1881). Magdalen Bridge. Pall Mall Gazette. London. Morris, W. (1887). [Hopes and Fears for Art]. Morris, W. (1894). How I Became a Socialist, Justice. Parkins, W. (Ed.). (2010). William Morris and the Art of Everyday Life. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

11 Pevsner, N. (2005). Pioneers of Modern Design: From William Morris to Walter Gropius (4th Edition ed.). New Haven: Yale University. Rickett, A. C. (1913). William Morris: A Study in Personality. New York: E. P. Dutton and Co. Rosenberg (Ed.). (1998). The Genius of John Ruskin: Selections from His Writings. Charlotte: University of Virginia. Steinberg, S. H. (1996). Five Hundred Years of Printing (3rd ed.). London: British Library and Oak Knoll Press. Thompson, E. A. (1955). William Morris. New York: Pantheon. Thompson, S. O. (1996). American Book Design New York: Abrams. Wiener, M. J. (1976). The Myth of William Morris. A Quarterly Journal Concerned with British Studies, 8(1), 67-82. Wilhide, E. (1991). William Morris: Decor and Design. New York: Abrams.

You might also like

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Plastic Properties HandbookDocument15 pagesPlastic Properties HandbookguilloteARGNo ratings yet

- Volvo BL 71 ManualDocument280 pagesVolvo BL 71 ManualAlberto G.D.100% (2)

- The Mooring Pattern Study For Q-Flex Type LNG Carriers Scheduled For Berthing at Ege Gaz Aliaga LNG TerminalDocument6 pagesThe Mooring Pattern Study For Q-Flex Type LNG Carriers Scheduled For Berthing at Ege Gaz Aliaga LNG TerminalMahad Abdi100% (1)

- Haraway"s A Cyborg ManifestoDocument15 pagesHaraway"s A Cyborg ManifestoFlorence Margaret Paisey50% (6)

- ENC1102 PaiseyFall2014 Miami Dade CollegeDocument14 pagesENC1102 PaiseyFall2014 Miami Dade CollegeFlorence Margaret PaiseyNo ratings yet

- Bennett Study PresentationDocument16 pagesBennett Study PresentationFlorence Margaret PaiseyNo ratings yet

- Natural and Quasi StudiesDocument4 pagesNatural and Quasi StudiesFlorence Margaret PaiseyNo ratings yet

- Research BarriersDocument9 pagesResearch BarriersFlorence Margaret PaiseyNo ratings yet

- Experimental DesignDocument8 pagesExperimental DesignFlorence Margaret PaiseyNo ratings yet

- Syllabus ENC 1102Document11 pagesSyllabus ENC 1102Florence Margaret PaiseyNo ratings yet

- Florence Margaret PaiseyDocument5 pagesFlorence Margaret PaiseyFlorence Margaret PaiseyNo ratings yet

- Lois Lenski CollectionDocument1 pageLois Lenski CollectionFlorence Margaret PaiseyNo ratings yet

- Syllabus English 1101Document11 pagesSyllabus English 1101Florence Margaret PaiseyNo ratings yet

- Florence Margaret Paisey, M.S., MLS, Ed.S.: Summary of QualificationsDocument5 pagesFlorence Margaret Paisey, M.S., MLS, Ed.S.: Summary of QualificationsFlorence Margaret PaiseyNo ratings yet

- UNIT 5-8 PrintingDocument17 pagesUNIT 5-8 PrintingNOODNo ratings yet

- Biotech NewsDocument116 pagesBiotech NewsRahul KapoorNo ratings yet

- Industrial ExperienceDocument30 pagesIndustrial ExperienceThe GridLockNo ratings yet

- Boundary Value Analysis 2Document13 pagesBoundary Value Analysis 2Raheela NasimNo ratings yet

- Magic Bullet Theory - PPTDocument5 pagesMagic Bullet Theory - PPTThe Bengal ChariotNo ratings yet

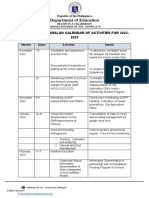

- GPP Calendar of Activities 2022 23 SdoDocument5 pagesGPP Calendar of Activities 2022 23 SdoRomel GarciaNo ratings yet

- Lacey Robertson Resume 3-6-20Document1 pageLacey Robertson Resume 3-6-20api-410771996No ratings yet

- I. Learning Objectives / Learning Outcomes: Esson LANDocument3 pagesI. Learning Objectives / Learning Outcomes: Esson LANWilliams M. Gamarra ArateaNo ratings yet

- CA21159 MG 8 Digital BookletDocument5 pagesCA21159 MG 8 Digital BookletcantaloupemusicNo ratings yet

- Pioneer 1019ah-K Repair ManualDocument162 pagesPioneer 1019ah-K Repair ManualjekNo ratings yet

- Universal Ultrasonic Generator For Welding: W. Kardy, A. Milewski, P. Kogut and P. KlukDocument3 pagesUniversal Ultrasonic Generator For Welding: W. Kardy, A. Milewski, P. Kogut and P. KlukPhilip EgyNo ratings yet

- 25 Middlegame Concepts Every Chess Player Must KnowDocument2 pages25 Middlegame Concepts Every Chess Player Must KnowKasparicoNo ratings yet

- Pathogenic Escherichia Coli Associated With DiarrheaDocument7 pagesPathogenic Escherichia Coli Associated With DiarrheaSiti Fatimah RadNo ratings yet

- Been There, Done That, Wrote The Blog: The Choices and Challenges of Supporting Adolescents and Young Adults With CancerDocument8 pagesBeen There, Done That, Wrote The Blog: The Choices and Challenges of Supporting Adolescents and Young Adults With CancerNanis DimmitrisNo ratings yet

- Financial Market - Bsa 2A Dr. Ben E. Bunyi: Imus Institute of Science and TechnologyDocument3 pagesFinancial Market - Bsa 2A Dr. Ben E. Bunyi: Imus Institute of Science and TechnologyAsh imoNo ratings yet

- Central University of Karnataka: Entrance Examinations Results 2016Document4 pagesCentral University of Karnataka: Entrance Examinations Results 2016Saurabh ShubhamNo ratings yet

- Universitas Tidar: Fakultas Keguruan Dan Ilmu PendidikanDocument7 pagesUniversitas Tidar: Fakultas Keguruan Dan Ilmu PendidikanTheresia Calcutaa WilNo ratings yet

- Pediatrics: The Journal ofDocument11 pagesPediatrics: The Journal ofRohini TondaNo ratings yet

- DirectionDocument1 pageDirectionJessica BacaniNo ratings yet

- Lodge at The Ancient City Information Kit / Great ZimbabweDocument37 pagesLodge at The Ancient City Information Kit / Great ZimbabwecitysolutionsNo ratings yet

- RARE Manual For Training Local Nature GuidesDocument91 pagesRARE Manual For Training Local Nature GuidesenoshaugustineNo ratings yet

- Yetta Company ProfileDocument6 pagesYetta Company ProfileAfizi GhazaliNo ratings yet

- 4.2.4.5 Packet Tracer - Connecting A Wired and Wireless LAN InstructionsDocument5 pages4.2.4.5 Packet Tracer - Connecting A Wired and Wireless LAN InstructionsAhmadHijaziNo ratings yet

- Assessment of Embodied Carbon Emissions For Building Construc - 2016 - Energy AnDocument11 pagesAssessment of Embodied Carbon Emissions For Building Construc - 2016 - Energy Any4smaniNo ratings yet

- Hele Grade4Document56 pagesHele Grade4Chard Gonzales100% (3)

- Chapter 10 Tute Solutions PDFDocument7 pagesChapter 10 Tute Solutions PDFAi Tien TranNo ratings yet

- Iguard® LM SeriesDocument82 pagesIguard® LM SeriesImran ShahidNo ratings yet