Professional Documents

Culture Documents

CC3Writer DesignerFriend

Uploaded by

Silvia HagemannOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

CC3Writer DesignerFriend

Uploaded by

Silvia HagemannCopyright:

Available Formats

Campaign Cartographer, the Writer / Designers Friend (Robin D.

Laws) Part 1 Better than the hideous scanned-in scrawl

Heres a paradox for you. I consider Campaign Cartographer an indispensable tool of my work as a game designer and writer and use it on a regular basis. I am at the same time a lousy mapper. When I see the gorgeous maps produced by Profantasys cadre of dedicated mapmakers and by its fan community, I am reduced to fits of envy.

After all these years of using the program, I lack mapping chops because I only infrequently use it for its intended purpose. Instead, Ive press-ganged it into service as an outlining tool. I use it to create product mock-ups, build diagrams for game books, and, most of all, visually organize my thoughts when plotting fiction projects.

Sure, as a designer of tabletop gaming products, I am occasionally called on to submit rough maps to my clients and do call on CC3 to save me time and effort on that front. Although I havent put in the time to to make the resulting roughs reliably attractive, the result is better than the hideous scanned-in scrawl Id otherwise be foisting on my saintly developers.

The ability to create background fills from photographs offers a quick and dirty way to make a submitted map look suitably spiffyat least for submission as a rough. Although I wouldnt want to see something like the example below published in a book, it at least gives the illustrator more to go on than the crude hand-sketch Id otherwise be handing him.

When walking around with my digital camera, I keep an eye out for interesting textures. Sometimes my inspiration for an encounter will come from the texture. Ill build the map around the texture, then the encounter around the map. For example, shots of mossy ground got me started creating the encounter map you see above.

Part 2 Moving stuff around

CC3 offers the primary benefit of a CAD-based illustration tool in a gamer-friendly form. Whether creating a map or using it for any of the purposes Ill discuss below, that benefit is ease of editing. It lets you think visually, by allowing you to easily and continually manipulate its various elements. Changing either an element or its position relative to others proves blissfully easy.

When sketching out an encounter map for publication, youre always going to realize midway through that you need to make an adjustmentyouve left a tactical bottleneck at the entrance, placed a trap where it wont get tripped, or given a confusing position marker to a creature. You can move stuff around in Photoshop or one of its equivalents, but its a pain. On paper, forget about it. Moving stuff around is what CC is all aboutfor me at least.

Without that function, the already time-consuming job of designing Mutant City Blues Quade Diagram would have been well, some things are too awful to contemplate. For those who dont know it, Mutant City Blues is a super-powered police procedural for the GUMSHOE line of investigative roleplaying games. A mystery game set in a world of super-powered heroes doesnt work unless all the extraordinary abilities have been documented and work predictably. In the MCB setting, all of the available super powers have been charted, cataloged, and placed on a relational diagram named after its primary discoverer, Dr. Lucius Quade. The diagram shows where powers cluster together on the genome. Youre highly likely to possess powers that cluster together on the chart and unlikely to manifest ones that are widely separated.

The Quade Diagram is both a rules and a world artifact. In the world, the characters employ it as a tool while solving their cases. In the game, players use it to choose and cost out their mutant powers. Because similar powers cluster together, I was forced to rearrange the chart whenever I realized that Id missed including an obvious comic book power and had needed to add it to the master list. The thought of completing each of these ongoing changes in a drawing-style illustration program fills me with existential dread.

The chart appears in gussied-up form in the published rule book. Below youll see what the work version looked like in Campaign Cartographer

Part 3 Developing fiction

Outlining a work of fiction is also about moving stuff around. Some writers prefer to hit the page and start writing, and then sort out the structure during subsequent revision rounds. Personally, I need to have the narrative line worked out in some detail before the first draft starts. Minor transitions and obstacles are often stronger if you think them through on the day, but the broad sweep has to be in place. (Outlines are also essential when youre working with an editor who has to sign off on your story before you start writing in earnest.)

Plotting never gets easy. For me, it typically starts with a few key situations or images. Then I bash around on a scratch document in which I trawl for some kind of unifying spine. During this phase I ask myself the defining questions shaping the story Im about to assemble. What is this story about, in a single sentence? Who are my characters? What drives them, and to what actions?

Once the answers to those questions have been nailed down, I fire up CC to move from a verbal conception of the narrative to a visual one. Basically Im taking the known elements of the story and treating them as dots Ill have to connect. Usually at this point Ill already have an opening sequence that poses the above questions and impels the protagonist into action. Chances are Ill also know the twist that changes his or her quest, and also a climax and conclusion. At this stage I now have to conceive the connective scenes that build engagingly toward those moments.

Screenwriters often place their plot points on index cards and move them around on a cork board. CC allows me to move them around on a virtual corkboard thats as big or small as I want it to be at any time. I can zoom in and zoom out as needed. And I transform the index cards into any kind of graphic element I want

Typically I use blocks of text, coded in some way to tell me which characters are involved in any given scene. This allows me to make sure that all of the characters develop as needed throughout the narrative. If I see that I havent got enough action for a major character, I might either create new prospective scenes for him, or realize that hes not really as important to the story as I thought. I might see that an apparently minor character is cropping up in many of the scenes, warning me to make him interesting enough to hold the readers attention for all of that time. I may need to introduce him earlier to suit his new weight in the narrative, leading to an insertion of one or more additional text blocks.

To visually represent characters, I doodle quick cartoony images, scan them in, and convert the resulting PNG file into a CC symbol. This allows me to easily drop the symbol representing each character over each plot point. If your doodling skills are even more primitive than mine, you could cast your characters from images found on the internet, converting them to PNGs if necessary and then to CC symbols.

A look at the diagram so far shows me the gaps I need to fill, if any, in my search for a narrative that is coherent on both the logical and the emotional levels.

To search for logic problems is to test the believability of the story (within whatever genre conventions it establishes.) What practical considerations within the world of the story am I glossing over? I might want Josie to be at the bridge with the bomb, but see that logically Jimbo would have stopped her back at the ranch. Having seen the problem, I have to either find a credible reason for Jimbo to cooperate with my plotting needsor concede that my story is contrived, and start over with a series of plot points that properly arise from the collisions of the characters competing intentions.

Above theres a detail from a CC fiction outline composed in index card fashion. Each box represents a major story beat. Character symbols identify the driving character in the scene; Ive also color coded the boxes to the driving characters:

I also want to be able to plot the emotional line of the story. So rather than simply connecting the plot points in a series of boxes, I use up and down arrows to see the shifts in fortune as the hero cycles between adversity and triumph. This approach wouldnt be needed for certain stories, in which its completely appropriate to stick with the same mood for long periods of time. Most narratives, though, genre or otherwise, keep us engaged by varying our hope and fear responses. Here I can see if I need to insert some relief into an otherwise down section, or find additional ways to challenge a protagonist who is having too easy a time of it.

The result can be a very long diagram. Its unwieldy on the page, but easy to scroll through on the screen. CC allows me to zoom out to see the storys entire narrative line, beat by beat, or zoom in to fix a problem area in need of revision.

Whenever I spot a scene that needs minor clarification, I can change the text element. If the whole thing needs changing, I can cut it and move the elements around it to fill its spot. Or add a new plot point as logic, inspiration or emotional rhythm require, creating a space for it by moving the adjoining plot points.

Heres an example. This is a work in progress for a client, so Ive disguised it by changing the beat labels to nonsense phrases.

Notice that the character symbols are sometimes scaled differently within a scene. Sometimes Ill want to indicate which characters are dominant in a scene, and which ones are hanging around on its periphery. The easy resizing of symbols allows me to scale the size of my character images with a few key strokes.

Ive also used layers to create alternate versions of a narrative map, each conveying different information. For a story featuring an ensemble cast, I created a column to the side noting which characters achieved defining victories in each installment of a serial narrative. At a glance I could see which characters werent registering strongly enough. I then added or replaced scenes in my outline to balance the contributions of each character to the story.

It may well be that no other author would map their narratives in exactly the same way. The up arrows and character icons might be more help than hindrance to someone else. Other writers might, for example, want to start by importing images of locations, organizing their plotting process geographically. They might want a layer of images keeping track of clues in a mystery story, or marking various ways in which the theme of the story is reinforced throughout.

However, the core ideaof using CC as an infinitely fungible and customizable virtual corkboardis one that any writer whos every juggled story elements or drawn a diagram might find useful, if not come to inescapably depend upon.

You might also like

- Mastering Comic ArtDocument33 pagesMastering Comic ArtAnderson Menara90% (10)

- Figure Drawing With The Mannequin ModelDocument17 pagesFigure Drawing With The Mannequin ModelkingsleyclementakpanNo ratings yet

- Outline Your Story Like A Subway MapDocument4 pagesOutline Your Story Like A Subway MapKeith ArmonaitisNo ratings yet

- Manga & Anime Digital Illustration Guide: A Handbook for Beginners (with over 650 illustrations)From EverandManga & Anime Digital Illustration Guide: A Handbook for Beginners (with over 650 illustrations)No ratings yet

- Photoshop & SketchUP - Comic Book LayoutDocument5 pagesPhotoshop & SketchUP - Comic Book Layoutxpajaroxhc100% (1)

- Ltd. - Manga Historical Characters (2013) PDFDocument37 pagesLtd. - Manga Historical Characters (2013) PDFArmando Suetonio Amezcua100% (5)

- Lo 4Document10 pagesLo 4api-263881401No ratings yet

- Character DesignDocument4 pagesCharacter DesignMark Rous50% (4)

- The Story Microscope: The Surprising Way a Spreadsheet Can Save Your ManuscriptFrom EverandThe Story Microscope: The Surprising Way a Spreadsheet Can Save Your ManuscriptNo ratings yet

- LitRPG Novel Storybuilder: TnT StorybuildersFrom EverandLitRPG Novel Storybuilder: TnT StorybuildersRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- The Perspective Drawing Guide: Simple Techniques for Mastering Every AngleFrom EverandThe Perspective Drawing Guide: Simple Techniques for Mastering Every AngleRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- TutorialDocument5 pagesTutorialLuiyi Lazcano MontalvoNo ratings yet

- Development Pro Forma FinDocument34 pagesDevelopment Pro Forma FinJacobNo ratings yet

- How To Outline Your ScreenplayDocument3 pagesHow To Outline Your Screenplayharsha100% (2)

- Entanglements: A Story Mapping Tool For Rpgs by Ewen CluneyDocument11 pagesEntanglements: A Story Mapping Tool For Rpgs by Ewen CluneyAce LukeNo ratings yet

- Principles and Concept of AnimationDocument7 pagesPrinciples and Concept of Animationrenz daveNo ratings yet

- Complete Guide to Drawing Dynamic Manga Sword Fighters: (An Action-Packed Guide with Over 600 illustrations)From EverandComplete Guide to Drawing Dynamic Manga Sword Fighters: (An Action-Packed Guide with Over 600 illustrations)Rating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (3)

- Checklist For IllustrationDocument6 pagesChecklist For IllustrationMD Aminur IslamNo ratings yet

- Storyboarding For RestaurantDocument8 pagesStoryboarding For RestaurantCeesay ModouNo ratings yet

- Compass Points - Building Your Story: A Guide to Structure and PlotFrom EverandCompass Points - Building Your Story: A Guide to Structure and PlotNo ratings yet

- EntanglementsDocument11 pagesEntanglementsCelso Dos ReisNo ratings yet

- How To Outline A NovelDocument18 pagesHow To Outline A NovelCarol XuNo ratings yet

- RPG Writing Good ScenariosDocument6 pagesRPG Writing Good ScenariosfyodoroprichnikbasmanovNo ratings yet

- Writing Scene FlowDocument4 pagesWriting Scene FlowMoon5627No ratings yet

- See What I Mean: How To Use Comics to Communicate IdeasFrom EverandSee What I Mean: How To Use Comics to Communicate IdeasRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Picture Yourself Writing Drama: Using Photos to Inspire WritingFrom EverandPicture Yourself Writing Drama: Using Photos to Inspire WritingNo ratings yet

- 12 Step Animation ProcessDocument13 pages12 Step Animation ProcessJoseph SubinNo ratings yet

- Digital Graphics EvaluationDocument28 pagesDigital Graphics EvaluationAnonymous 05i3Vq4GNo ratings yet

- Adventure Design in PracticeDocument26 pagesAdventure Design in PracticebqrneaqbjwpyespxpgNo ratings yet

- Storytelling in Words and Pictures: How To Write Graphic Novels and ComicsDocument24 pagesStorytelling in Words and Pictures: How To Write Graphic Novels and ComicsJanet Stone100% (4)

- Romcom Structure Made Easy: A Screenwriter's Guide to the Six Essential Movie Plot Points and Where to Find Them in 29 Favorite Romantic ComediesFrom EverandRomcom Structure Made Easy: A Screenwriter's Guide to the Six Essential Movie Plot Points and Where to Find Them in 29 Favorite Romantic ComediesNo ratings yet

- Drawing Superheroes in Action Book II - (A Guide to Drawing Body Movements) For the Absolute BeginnerFrom EverandDrawing Superheroes in Action Book II - (A Guide to Drawing Body Movements) For the Absolute BeginnerRating: 1 out of 5 stars1/5 (1)

- EntanglementsDocument11 pagesEntanglementsOmen123No ratings yet

- Comics 101 - Dibujo de FiguraDocument10 pagesComics 101 - Dibujo de Figuraoctavio_r3100% (3)

- High ConceptsDocument6 pagesHigh ConceptsDanNo ratings yet

- Tdw72 T ZbrushDocument6 pagesTdw72 T ZbrushKALFERNo ratings yet

- 15 - How To Make An Animated MovieDocument13 pages15 - How To Make An Animated MovieShinbouNo ratings yet

- Title Sequence EvaluationDocument1 pageTitle Sequence Evaluationapi-632047644No ratings yet

- Outlining Your Novel Workbook: Step-by-Step Exercises for Planning Your Best BookFrom EverandOutlining Your Novel Workbook: Step-by-Step Exercises for Planning Your Best BookRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (23)

- How To Rewrite Your ScreenplayDocument8 pagesHow To Rewrite Your ScreenplayManny ResendizNo ratings yet

- Thesis VFXDocument8 pagesThesis VFXbeacbpxff100% (2)

- How to Self-Publish: The Essential Guide for Taking Your Idea to Market: The Author LifeFrom EverandHow to Self-Publish: The Essential Guide for Taking Your Idea to Market: The Author LifeNo ratings yet

- The 12 Key Pillars of Novel Construction: The Writer's Toolbox SeriesFrom EverandThe 12 Key Pillars of Novel Construction: The Writer's Toolbox SeriesRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Story Structure For The Win - Ho - H. R. D'CostaDocument114 pagesStory Structure For The Win - Ho - H. R. D'Costapratolectus100% (2)

- How Do I Give My Main Protagonist Their MotivationDocument9 pagesHow Do I Give My Main Protagonist Their MotivationKatrin NovaNo ratings yet

- CLC 12 - Capstone Draft Proposal WorksheetDocument3 pagesCLC 12 - Capstone Draft Proposal Worksheetapi-638532998No ratings yet

- The Exceptionally Simple Theory of SketchingFrom EverandThe Exceptionally Simple Theory of SketchingRating: 2 out of 5 stars2/5 (1)

- 8 CharracDocument4 pages8 CharraccelinNo ratings yet

- Dharu PDFDocument2 pagesDharu PDFRupai SarkarNo ratings yet

- Portfolio PlanningDocument7 pagesPortfolio PlanningLinneyL1993No ratings yet

- NAnsari Islamic Garden RDocument48 pagesNAnsari Islamic Garden RSilvia HagemannNo ratings yet

- iaSU2012 Proceedings 109Document6 pagesiaSU2012 Proceedings 109Silvia HagemannNo ratings yet

- Master's Thesis, 60 ECTS Social-Ecological Resilience For Sustainable Development Master's Programme 2015/17, 120 ECTSDocument61 pagesMaster's Thesis, 60 ECTS Social-Ecological Resilience For Sustainable Development Master's Programme 2015/17, 120 ECTSSilvia HagemannNo ratings yet

- Cultivating Sentiment and Soul and Poetically LivingDocument3 pagesCultivating Sentiment and Soul and Poetically LivingSilvia HagemannNo ratings yet

- Yutong-Design Analysis of Classicial Chinese GardensDocument20 pagesYutong-Design Analysis of Classicial Chinese GardensSilvia HagemannNo ratings yet

- On Chinese Gardens Bibliography of ItemsDocument148 pagesOn Chinese Gardens Bibliography of ItemsSilvia HagemannNo ratings yet

- URLLinkDocument1 pageURLLinkSilvia HagemannNo ratings yet

- 201000hidden Orders in Chinese Gardens - Irregular Fractal Structure and Its Generative RulesDocument20 pages201000hidden Orders in Chinese Gardens - Irregular Fractal Structure and Its Generative RulesSilvia HagemannNo ratings yet

- Analysis of The View of Time and Space in Chinese Classical GardensDocument9 pagesAnalysis of The View of Time and Space in Chinese Classical GardensSilvia HagemannNo ratings yet

- Henna Knot Work FreeDocument25 pagesHenna Knot Work FreeCristina FigueiraNo ratings yet

- The 16 Guidelines For Life: Study ProgrammeDocument17 pagesThe 16 Guidelines For Life: Study ProgrammeSilvia HagemannNo ratings yet

- License Agreement: Use of This Software Is Determined by A License Agreement You Can View On The CDDocument22 pagesLicense Agreement: Use of This Software Is Determined by A License Agreement You Can View On The CDSilvia HagemannNo ratings yet

- Command ListDocument50 pagesCommand ListSilvia Hagemann100% (1)

- Sudbury ExampleDocument1 pageSudbury ExampleSilvia HagemannNo ratings yet

- A Rough Guide To Castle Design Part 1 - Who? and Why?Document5 pagesA Rough Guide To Castle Design Part 1 - Who? and Why?Silvia HagemannNo ratings yet

- Anon - English HuntsuppeDocument1 pageAnon - English HuntsuppeIsaac SharpNo ratings yet

- Dreams and Illusions of Astrology Science The Paranormal Series by Michel GauquelinDocument5 pagesDreams and Illusions of Astrology Science The Paranormal Series by Michel GauquelinCarla Coelho BatistaNo ratings yet

- An Introduction To British RomanticismDocument5 pagesAn Introduction To British RomanticismRayan DNo ratings yet

- I Taste A Liquor Never BrewedDocument19 pagesI Taste A Liquor Never BrewedLê Thanh Trúc AngelNo ratings yet

- DDEP3 Blood Above Blood Below AdminDocument2 pagesDDEP3 Blood Above Blood Below AdminRobert Scott100% (1)

- Shattered ReflectionsDocument261 pagesShattered ReflectionsisipareNo ratings yet

- Mike White's Top 10 Books - Radical ReadsDocument8 pagesMike White's Top 10 Books - Radical ReadsngaliNo ratings yet

- Seamus Heaney DanteDocument13 pagesSeamus Heaney Dantekane_kane_kaneNo ratings yet

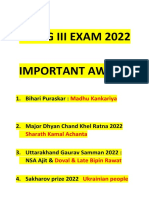

- Awards 2022Document17 pagesAwards 2022Armstrong SinghNo ratings yet

- Butterfly Lovers: A Chinese StoryDocument1 pageButterfly Lovers: A Chinese StoryAnyta RamirezNo ratings yet

- The Selfish Giant SummaryDocument3 pagesThe Selfish Giant Summaryrajeev0% (2)

- Cause & Effect Conjuncti Ns Exercises: - Go To TheDocument5 pagesCause & Effect Conjuncti Ns Exercises: - Go To TheJean CabingatanNo ratings yet

- 21ST Century Literature Grade 11Document80 pages21ST Century Literature Grade 11Gaming Account50% (2)

- Book Review - The TelephoneDocument2 pagesBook Review - The TelephoneKavvyaNo ratings yet

- Mordheim Albion ExpansionDocument11 pagesMordheim Albion ExpansionConor100% (1)

- MR Darcy's Diary: Maya SlaterDocument14 pagesMR Darcy's Diary: Maya Slatershush10100% (1)

- Famous Monsters of Filmland 006 1960 Warren PublishingDocument69 pagesFamous Monsters of Filmland 006 1960 Warren Publishingdollydilly83% (6)

- Project in English 10Document7 pagesProject in English 10Princess AbalosNo ratings yet

- Grade 4 - Wonders Reading Writing WorkshopDocument481 pagesGrade 4 - Wonders Reading Writing WorkshopMicheleLemes88% (17)

- A Dream of UnknowingDocument218 pagesA Dream of UnknowingAndy MeliaNo ratings yet

- Test On Unit 7Document6 pagesTest On Unit 7yosof essamNo ratings yet

- The Dolls of New Albion: A Steampunk Opera LibrettoDocument29 pagesThe Dolls of New Albion: A Steampunk Opera Librettosingingrock1350% (2)

- The Functions of Sound and Music in Tarkovsky S FilmsDocument9 pagesThe Functions of Sound and Music in Tarkovsky S FilmsJunior CruzNo ratings yet

- NaturismDocument19 pagesNaturismBhavana AjitNo ratings yet

- Secondary Education Curriculum Observation Sub-Cycle (Form 1, Form 2)Document88 pagesSecondary Education Curriculum Observation Sub-Cycle (Form 1, Form 2)Epie Frankline100% (1)

- American Survey - of Mice and Men - Study GuideDocument2 pagesAmerican Survey - of Mice and Men - Study GuideguyNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2 Section 2 Sentence Patterns PDFDocument39 pagesChapter 2 Section 2 Sentence Patterns PDFJorge Mendez100% (3)

- Kobold Press - Guide To MonstersDocument114 pagesKobold Press - Guide To MonstersFulya50% (2)

- Film and The Critical Eye - BookDocument555 pagesFilm and The Critical Eye - Bookturcuancaelisabeta50% (2)

- 130057dossier Pedagogique Shakespeare Web EngDocument8 pages130057dossier Pedagogique Shakespeare Web EngM. HonorezhNo ratings yet