Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Kiernan V.G. 1959 'Culture and Society' The New Reasoner, No. 9 (Pp. 75 - 83)

Uploaded by

voxpop88Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Kiernan V.G. 1959 'Culture and Society' The New Reasoner, No. 9 (Pp. 75 - 83)

Uploaded by

voxpop88Copyright:

Available Formats

The New Reasoner Summer 1959 number 9 V. G. KIERNAN . G.

Kiernan : Culture and Society 75

Culture and Society

Culture is one of those words that space-fiction writers let their heroes translate glibly into the languages of whatever planets they land on, forgetting that in order to convey any distinct meaning to their six or ten-legged audience they would need to go over most of the history of the human race. In its modern bundle of meanings the word is new. The things it means are, most of them, very old. Every social group, every community, has had its ' culture', and in all complex societies culture has performed utilitarian as well as spiritual duties; it has been a badge of ranks, and a potent instmmentum regni, or preserver of order and subordination. A pyramid, a Norman cathedral, a Taj Mahal, all serve to impress on the common run of mortals the grandeur and glory of their masters, and of all the purposes they serve none is more important than this. The functioning of culture within the evolution of human society has been too little studied; and we may put this in another way by saying that there has been too little study of the class of men (or ' species', ' order', ' family ', or however we choose to classify it), who have been primarily concerned with culture. In English we have not even a name for this section of the conglomerate ' middle classes ', unless the makeshift ' intelligentsia'. It could be defined in a rough and ready way, for all but very recent times, as the body of men habitually occupied with reading and writing; though it must be added that their knowledge has always been connected with a variety of practical skills, not with abstractions only. These men have not ruled the world, but they have in most times and places managed it. History is made much too simple when its ruling classes are imagined to be always ruling, perpetually exerting their categorical imperative. They govern directly only with respect to their vital interests, or in times of crisis. The learned class which they employ has not sat crosslegged through history in the posture of the Scribe, waiting with blank face and blank mind to write down Pharaoh's commands, whether of life or of death. It has been the mediator between those above it and those below, the interpreter of their experience of life as well as of its own, the sensitive recorder of all the community's strains and tremors, the repository of all its knowledge and all its arts; it has been to the body politic ' the soul with all its maladies '. One of the earliest, and far the most effective of all investigators of culture and society was Confucius, and China stands out

through more than two millennia as the land where art and letters and philosophy were welded into almost unbreakable union with the structure of family, village, empire, and where the sword was almost hidden behind the pen. In the culture-history of our own continent nothing stands out more formidably than that grandiose experiment in ' social engineering', the Counter-Reformation, which mobilised every resource of art, ideology, indoctrination, along with supplies of free soup for the docile and thumbscrews for the indocile, to dam and turn the current of history over half Europe, and divide the continent for three centuries into a region of stagnant acquiescence and a region of dynamic unrest; a bifurcation that Europe runs some risk of undergoing again ' right now'. Mr. Williams in his Culture and Society 1780-1950* is not writing a history of the culture of modern Britain, either in the very wide sense in which he sometimes employs the word (e.g., p.233), as equivalent to civilization, the sum total of a community's ' way of life', or in its narrower, more familiar sense of the complex of arts and letters. His problem is a subtler one; not altogether easy to grasp as he formulates it at the outset (p.xviii), and not always simple to follow from point to point as he proceeds with it, for there is a shifting emphasis on certain political, certain artistic, and certain social aspects or offshoots of the subject. Broadly, however, he is concerned with the development of a concept of, or attitude to, culture, in the consciousness of a series of representative thinkers, nearly all of whom would fit within a fairly close definition of ' intelligentsia'. It is that of loyalty to the tradition of an organic, integrated society which had a place for all its members and some paternal care of all, and in which the arts, like all other callings, claimed an active share in the right conduct of the collective life, instead of being divorced from it. Mr. Williams is scrutinising this tradition in a modern epoch of economic change and separation and alienation of class from class, accompanied by emergence of a turbulent pressure towards Democracy and consequent danger of social anarchy. He sees his thinkers as men struggling, in a changing and challenging environment, to defend and adapt the values handed down from an earlier and more ' nautral' social order. Two leading comments on his work suggest themselves. One is that he has written a fascinating and important book, remarkably well stored with good things. The second is that the prime requisite for any study of cultural history is a firm framework of * Chatto and Windus, 1958: 30s.

76

The New Reasoner

V. G. Kiernan : Culture and Society

77

historical fact - economic, social, political; and that the one great deficiency of the book is the lack of just this. Mr. Williams starts with the Industrial Revolution, because he considers that the idea of culture, as well as the word, ' came into English thinking' then (p.vii). This is surprising, for the Elizabethans, to look no further back, breathed the idea in with every mouthful of air. Mr. Williams himself notes, too briefly, that many elements of the notion of culture derive from Humanism (p.24). But if the Industrial Revolution is to be the starting-point and primum mobile, he would have helped his readers greatly by beginning with a sketch of what he considers it, and its main social effects, to have been. Instead he leaves it as something to be taken for granted, a backcloth strung across his stage with a rough charcoaling of grimy mills and smoky stacks. Nor on the other hand does he draw any outline of the social order, the ' way of life', he thinks of as flourishing in England before 1780. It is left to the reader to guess how far the notion of a once healthily integrated society corresponds either with historical reality or with Mr. Williams' own view of historical reality. Mr. Williams indeed leaves far too much room for supposing that he himself takes the ' good old days' at their face value. It is late in the book, and then somewhat perfunctorily, that he comes to discuss them as myth. It is surely crucial to ask how far the tradition he is studying was a true recollection, how far an illusion - and if the latter, how far wilfully indulged, or deliberately conjured up. It might be safe to say that something akin to this tradition has haunted men's minds since society first began, and that in its truest outlines it is the memory of a city never built at all, and therefore built for ever. But within the limits of pedestrian English chronicles the disintegration of an old community consciousness must be set long before 1780. There was a battle of ideas in the 16th century about State, society and culture (mainly religious), and in the 17th a battle of pike and musket that ended with the dismantling, morally and administratively speaking, of most of what was left of the old paternalism. In the brief, uneasy stabilisation of the 18th century, whose culture as well as economy Mr. Williams neglects, he might have pointed to a partial rehearsal of the social reactions he has observed in the 19th. If Democrats had not yet reared their head, Levellers had. One defensive reaction was to hide one's common humanity under a preposterous wig. Another was to read Addison and Johnson, and cultivate selfculture. Leaving all this out leads Mr. Williams insidiously on to another silence. He allows his traditionalists to go on one after

the other, without any contradiction from him, founding their case on the assumption that what the Industrial Revolution brought to England was something essentially new, and essentially bad. He lets them use, and himself uses throughout, to denote the new order of things confronting the old Tradition, the word industrialism, coined in the 183O's as he remarks (p.72) by Thomas Carlyle. In the 1950's we require something vastly more precise, coined by someone vastly less muddle-headed and wrong-headed than Thomas Carlyle. Industrialism as a label has the cardinal vice of confounding two things that differ- toto coelo, or sometimes toto inferno - differ, in plain English, like chalk and cheese: mechanised labour in factories, and production by large-scale private enterprise. One relates to the technique of production, the other to the relations of production. From the point of view of impact on the consciousness of ordinary people it is the second that counts. Electricity and aeroplanes surprise an Asiatic or an African surprisingly little; wage-labour surprises him a great deal. Traditionalists denouncing Industrialism were often thinking merely of the outside, the grimy factory and the belching chimney. Sometimes (as in the fine passage quoted from Robert Owen on p.28) they were attacking, what mattered far more, the inner essence, the moral and social evil of a productive system based on blind accumulation and unrestricted competition. In one word, they were attacking capitalism. None of them could do this, with any degree of consistency, in the name of a social order existing before the steam-engine. England had been a capitalistic, though not a steam-operated, society since the 17th century. Wars for trade, plundering of colonies, slave plantations, enclosures, rackrenting of Highland valleys, sweated labour in cottage and coalmine, were all rife long before 1780; above all, the reduction of the ordinary Englishman - even though still living on the land - to the status of a hired labourer was already far advanced. Belching factory chimneys brought home more forcibly to philosophers that the times were changing, but they made by themselves no fundamental change in the structure of social relations; their smoke it may be added prevented many philosophers from noticing many other things that were now in the air. And ugly as the mills were, and bad in various worse ways, a lot of people hurried into them as soon as they began to spring up, glad of steadier work and better wages than they could get in the village; much as in our own day all the poor nations of the earth are to be seen pushing and jostling their way towards that ' Industrialism' over whose gateway Mr. Williams's men of culture wrote their All hope abandon.

78

The New Reasoner

V. G. Kiernan : Culture and Society

79

To be seen in the round, and understood in its real bearings, a pattern of ideas must be seen taking shape in the minds of members of a determinate social group in a specific epoch. Mr. Williams's method in this book has been to take a number of individual publicists of each generation in turn, extract passages from their works, and add his comments. His plan has the merit of simplifying an extremely complex and difficult undertaking. His extracts are excellently chosen and arranged, and his comment is penetrating and illuminating. Nevertheless a procession of individuals does not add up to a class. We are not shown the literati in their social setting, as a congeries of clans and corporations with specific functions and specific links and points of contact with the other classes. There are only scattered references to the particular kind of ' common m a n ' who stood on one side of them in 19th century England; no reference at all to the particular kind of ruling-class man who stood on the other side; and, as the book proceeds from decade to decade, very little reference to the rapidly altering condition of England. As a result these writers have somewhat the style of disembodied intelligences, spirit-voices addressing us through the lips of a medium. Part 1 of the book, the longest and in many ways most significant of its three divisions, goes to 1880. It opens with two contrasting pairs of thinkers, Burke and Cobbett, and Southey and Owen, all of whom are brought together as men judging an evil present ' in the terms and accents of an older England' (p. 3). Although this bracketing is usefully suggestive, Owen and Cobbett owed much of their strength to their firm foothold outside the intellectual class to which the others belonged; and Cobbett's ' good old days ' owed much of their flesh and blood, or corroborative detail, to the living world of equalitarian well-being that he found in America. In any case what most moved his indignation was the oppressive agrarian capitalism of the age, long in train though intensified by the Napoleonic wars, and scarcely to be brought under the black flag of ' industrialism '. It is a longish leap to the next chapter, on ' T h e Romantic Artist', which is one of the best in the book, even if it seems not to fit quite snugly at all its corners into Mr. Williams's framework. He sees the Romantic poet invoking, in opposition to a civilization corrosive of all standards, the permanent values both literary and ethical of the traditional culture. The criticism seems permissible that by conferring on all his characters the same paternity, or fitting them all into one fundamentally conservative category, he is letting himself see at best only half of what Englishmen had really handed down to one another from age to age. Wordsworth's

theory of diction was after all directed against the aristocratic culture of the pre-industrial 18th century, the culture of heroic couplet and man trap; and Blake when he wrote of the harlot's curse and the soldier's blood was following a long humanitarian tradition of condemnation of things that were part and parcel of the old regime - evils among which the Satanic mill made only one more, and which indeed were in part the reason why the mill was Satanic. In other words, if the Tradition meant more than mere self-complacency it was because England had a record never long interrupted of popular resistance to society as it was, and of writers ready to put the feelings of the people into language. Another long jump carries us into the Victorian world, where we find J. S. Mill striving to reconcile and synthesize the philosophies of Bentham and Coleridge. Mr. Williams sees in Coleridge the originator of Culture as a leading concept (p.59), and among other things describes Coleridge's quaint notion of a clerisy, an intelligentsia endowed like a national church to cultivate all arts and sciences and hold the balance of civilisation (pp.63-4). It is a recurrent dream of intellectuals, always most completely at the mercy of the Establishment when dreaming most headily of total independence or of sovereign sway, as some mediaeval priests dreamed, or Bacon in Atlantis, or as Swift in Laputa laughed at them all for dreaming. Coleridge's clerisy was only half way past being a clergy. Over vastly the greater part of its career in the world the intellectual class has had to shelter inside priestly vestments; and it is a pervading omission of Mr. Williams's that he takes little account of the religious history of his period. Another point that one would have liked him to find some room for is the influence of Scotland and Ireland in supplying England with immigrant intellectuals, as well as labourers, from regions to a great extent pre-industrial. His next chapter would have offered an opportunity, being on Carlyle, whose roots were in a society only just emerged from a condition more feudal than modern, at once closely integrated and highly authoritarian. Mr. Williams makes too little perhaps of Carlyle's always great and always increasing contempt for the mass of his fellow-beings, whom he imagined grovelling before a God-given aristocracy and imploring its rule and guidance very much as the Kirk saw the human race - ' Frail children of dust, and feeble as frail' - grovelling before the Almighty. Chapter 5, with another shift from the political to the literary tack, discusses the working-class and its trials and efforts at emancipation in novels by Mrs. Gaskell, Dickens, Disraeli, Kingsley, and George Eliot. It is remarkably impressive both on problems of writing (e.g., on 'character drawing', p. 104), and in

80

The New Reasoner

V. G. Keirnan : Culture and Society

81

analysis of political attitudes, conscious or unconscious, among these novelists. They all shared a sympathy with the workers, and a nervous shrinking from any involvement with the workers jn active struggle, an excessive mistrust of ' violence ' or ' anarchy' that Mr. Williams forcibly compares with Cobbett's robust language about riots (p. 105). His remark that the plot of Mary Barton was altered partly because its publishers objected to anything savouring of revolutionism suggests a general question about how much influence was exerted on Victorian fiction by ' censorship' in the form of the necessity of pleasing publishers and respectable readers. What is lacking to this whole picture of 19th century thought is recognition of how both good-will and hesitancy were rooted in a social environment. These individuals were embedded in a group whose habits, interests, points of view they could hardly help being in all sorts of ways influenced by. It was the group whose traditions and instincts past, present and future ran in service to the State, immediately or through those clerical, legal, educational corporations that represented its buttresses or outworks. We think habitually of our eminent writers as so many Stylites, each perched solitary on his pillar. It is useful to think of them at times as figures wedged inconspicuously into the second row in snapshots in family albums. Southey, Coleridge, Wordsworth, are then seen hemmed in among naval brothers, legal cousins, clerical uncles, including the real notables of the family who are on their way to the dignities of Judge, Bishop, or Master of a College. Among these professional clans there was undoubtedly a tradition, quickly picked up by new entrants too, a sense of society's responsibility to its members, starting but not finishing with the penal code; an instinct of paternalism that helped them to think as Arnold thought. It would be wrong not to see at the same time that more mundane impulses were at work. A Benthamite businessman wanted the State-apparatus stripped down to the barest skeleton because (philosophy apart) he had nothing to do with it except helping to pay for it. Men of the professional groups looked with favour on an expanding State machinery of inspection, protection, and spiritual uplift because (philosophy again apart) they would get the jobs; much as their cousins the smaller landed gentry approved of colonial expansion. It must be observed too that the men of culture, denouncing factories and Philistines, were taking their tone a great deal too easily from the landed interests which were their own old familiar employers. Their corporate existence with all its claret and amenities rested far too much on holdings of land - College estates and livings, Church glebes and

tithes; in other words it rested on the depressed existence of farm labourers who could be exploited as intensively as millworkers, but more quietly and decently because they could not combine and resist. Men of culture stood in even closer contact with another depressed class, the immense army of domestic servants, which through most of the century must have been a good deal bigger than the industrial proletariat and not as a rule either better paid or better treated. The famous Victorian comfort was the eiderdown that kept culture warm, and the comfort of drawingroom and study depended on the discomfort of garret and basement. There were two nations under every respectable Victorian roof. This was in short in a diversity of ways a Mandarin culture, that had not quite outgrown the common-rooms of Oxford. There was a strong admixture of snobbery in its mode of looking down on Philistinism, and on what it called ' trade'. If it shrank sensitively from the ugliness of factories, it shrank also from machinery, which is seldom, and Science, which is never ugly. A man like Nasmyth, artist and scientist as well as inventor and millowner, could have taught it much. It sometimes forgot that ugliness, slums and squalor did not come into the world with ' industrialism '. There is no lower depth of artistic or spiritual squalor than that of the third-rate baroque church in an average Italian street and its pious bric-a-brac of daubs and images. A Primitive Methodist chapel is a Parthenon to it. Whatever the more idealistic thought, prevailing notions of what ought to be done for the lower orders went very little beyond elementary education. Even in this England's performance was extraordinarily poor. After all, to supply the thinnest wine of culture to everybody would be troublesome, expensive, uncertain and - possibly - undesirable, A cheaper and better-tried substitute Jay to hand in religion: the small sour beer of Sabbatarianism, Sunday-schools, charities, missionary talks about poor benighted heathens. These, along with clerical control of education (such as there was) from top to bottom, were the means relied on to make the English one community again. We do not hear of Victorians giving drawing lessons to their kitchen-maids, or reciting Tennyson in the stable. Like Mr. Pontifex they flogged their children, and rang for family prayers. Part 2 of the book, 1880 to 1914, is entitled ' Interregnum ', and contains six studies. One on Shaw and Fabianism is the most Political, one on ' New Aesthetics' the least, and a very welcome essay on Gissing brings the two poles closer together. These years strike Mr. Williams as containing little that is really new (p.161).

82

The New Reasoner

G. Keirnan : Culture and Society

83

He might surely have found something new and noteworthy by bringing in Kipling and giving him the place of a major prophet of culture as the shared experience and consciousness of a community. It is surprising that neither nationalism nor imperialism is in his list of key new words (p. xvii; there is a momentary allusion to them right at the end on p.326). The Victorians had not been overly successful with religion, which is a potent preservative of community sense but cannot speedily re-create it when lost. A fresh substitute was required before the end of the century, and Heaven was replaced by the Empire, which had the advantage of not being (like matter in the old schoolbooks) colourless, tasteless, soundless and odourless. Not much objection was raised by the intelligentsia; and if here again we regard it as a social group with stomach and pocket as well as soul we shall recognise that imperialism was the solution towards which the logic of its own development had been impelling it. Its members, including a galaxy of its greatest writers, had innumerable family ties with the empire, especially India. Its hysteria at times like the Mutiny would otherwise be incomprehensible; and both its uneasy social conscience and its dread of mass revolt at home must have been aggravated by the chronic fear of revolt in the colonies. But the grand discovery of the late 19th century was the ease with which the mass of Europeans could be got to revel in the sensation of being freemen of the world's ruling class, the illusion that colonies and armies and navies belonged to them. Mr. Williams's Interregnum is oftener and better called the Age of Imperialism, and the renovated common consciousness of modern nations has been made up as to nine parts in ten by envy, fear and hatred of their neighbours. On Mafeking night long-divided England found herself at last one nation again, one band of brothers gloriously reunited on methylated spirit. In Part 3, on the latest period, Mr. Williams continues to be a most eligible guide, not least because he has the gift or attainment of never getting into a passion. Occasionally his approach to his authors is almost too civilised for a rough world. He is very instructive on Orwell, and (p.287) the vogue of Orwellian disillusion; and on D. H. Lawrence. In a way the debate he is reporting grows more academic at this stage, with the practical choice between capitalism and socialism now set clearly before the world. What was conservative in the old tradition grows unmistakably reactionary, and hugs to itself theories according to which genuine culture is beyond the capacity of more than a narrow elite; the rest of mankind presumably having to be supplied with

rattles and dummies. History is likely to refute these theories faster than logic can. In the Punjab the ordinary, ordinariest man lias some relish of poetry; in Russia, of science; if in Britain neither the one nor the other, the fault may not be in her stars. The forty pages of Mr. Williams's ' Conclusion ' are a discursive tract for the times, whose text may be found in an admirable sentence on p.317: ' W e need a common culture, not for the sake of an abstraction, but because we shall not survive without it.' It is for all of us to ask whether our Welfare State with its cosy Happy Families atmosphere is supplying us with a genuine common culture or one more substitute for it, one new piece of Ersatz. Mr. Williams does not gather up all the questions his enquiry has raised. He leaves on one side, notably, the problem of the State, in order to concentrate on that of society and individual. His own philosophy comes out again in another dictum: ' There are in fact no masses; there are only ways of seeing people as masses ' (p.300) - a difficult saying, and perhaps more an ideal for the future than a truth of past or present. One authentic feature of all traditional societies was the Tory Mob in its multitude of guises, drilled in our improving age into an S.S. Division. But the book is difficult altogether, though lucid and urbane, because its subject is difficult. It might not be amiss to call it a collection of penetrating essays rather than a finished whole; there will however be few readers whom it does not jog into doing some thinking on their own. This it is to be hoped will be especially true of Marxist readers who will (or should) feel indebted to Mr. Williams for his summary, in a chapter near the end, of the gaps and ambiguities in their theory of culture as so far developed. What is needed, let it be repeated once more, is further investigation into the history of culture combined with the history of the ' cultural' class. The relative autonomy of art and philosophy from the economic compulsion of their epoch is the same problem on another plane as the relative autonomy of the intelligentsia within the power-structure of class society. There are other reasons why this class, with the longest continuous tradition of any now existing in the world - the oldest regiment still of the line - should look back more carefully over its own evolution, its triumphs and its wanderings 'in wildernesses, because it is only through understanding its past that it will learn in our day to steer between false activity and inactivity, and play its very great part, which no other class can undertake for it, in the further advance of civilisation.

You might also like

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Ndalilah, Joseph W. 2012 'Migrant Labour in Kimilili, Kenya - Capitalism and African Responses, 1940 - 1963' JETERAPS, Vol. 3, No. 5 (Pp. 701 - 709)Document9 pagesNdalilah, Joseph W. 2012 'Migrant Labour in Kimilili, Kenya - Capitalism and African Responses, 1940 - 1963' JETERAPS, Vol. 3, No. 5 (Pp. 701 - 709)voxpop88No ratings yet

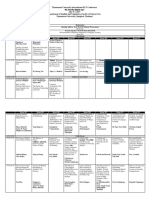

- GRADES 1 To 12 Daily Lesson Log Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday FridayDocument6 pagesGRADES 1 To 12 Daily Lesson Log Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday FridayAldren CruzNo ratings yet

- Ostrom, Elinor 2011 'Background On The Institutional Analysis and Development Framework' Policy Studies Journal, Vol. 39, No. 1 (Feb. 15, Pp. 7 - 27)Document21 pagesOstrom, Elinor 2011 'Background On The Institutional Analysis and Development Framework' Policy Studies Journal, Vol. 39, No. 1 (Feb. 15, Pp. 7 - 27)voxpop88No ratings yet

- Kellner, Douglas 2005 'Western Marxism' in Austin Harrington 2005 'Modern Social Theory - An Introduction' (Pp. 154 - 174)Document26 pagesKellner, Douglas 2005 'Western Marxism' in Austin Harrington 2005 'Modern Social Theory - An Introduction' (Pp. 154 - 174)voxpop88No ratings yet

- Romanza de La DuquesaDocument7 pagesRomanza de La DuquesaBrigitte ElvenoireNo ratings yet

- ENGLISH 6 Week 6 LessonDocument4 pagesENGLISH 6 Week 6 LessonElsieJhadeWandasAmando100% (1)

- Goisman, Berry 2007 'What Is Dialectic - Some Remarks On Popper's Criticism' (11 PP.)Document11 pagesGoisman, Berry 2007 'What Is Dialectic - Some Remarks On Popper's Criticism' (11 PP.)voxpop88No ratings yet

- Benn, Denis 2004 'Development Policy - Changing Perspectives and Emerging Pardigms' Presentation, ECLAC, Trinidad and Tobago (May 24 - 25, 22 PP.)Document22 pagesBenn, Denis 2004 'Development Policy - Changing Perspectives and Emerging Pardigms' Presentation, ECLAC, Trinidad and Tobago (May 24 - 25, 22 PP.)voxpop88No ratings yet

- Haggard, Stephen K. & John S. Howe 2007 'Are Banks Opaque' (Jan. 11, 41 PP.)Document43 pagesHaggard, Stephen K. & John S. Howe 2007 'Are Banks Opaque' (Jan. 11, 41 PP.)voxpop88No ratings yet

- Semiotics of Ideology: Winfried No THDocument12 pagesSemiotics of Ideology: Winfried No THvoxpop88No ratings yet

- Kay, Cristobal 2005 'Andre Gunder Frank - From The 'Development of Underdevelopment' To The 'World System''Document8 pagesKay, Cristobal 2005 'Andre Gunder Frank - From The 'Development of Underdevelopment' To The 'World System''voxpop88No ratings yet

- Social Movements, Civil Society and Land ReformDocument29 pagesSocial Movements, Civil Society and Land Reformvoxpop88No ratings yet

- Pastor, Robert A. 1992 'The Carter Administration and Latin American - A Test of Principle' The Carter Center (July, 85 PP.)Document85 pagesPastor, Robert A. 1992 'The Carter Administration and Latin American - A Test of Principle' The Carter Center (July, 85 PP.)voxpop88No ratings yet

- Munck, Ronaldo 1999 'Dependency and Imperialism in The New Times - A Latin American Perspective' EJDR, Vol. 11, No. 1 (June, Pp. 56 - 74)Document20 pagesMunck, Ronaldo 1999 'Dependency and Imperialism in The New Times - A Latin American Perspective' EJDR, Vol. 11, No. 1 (June, Pp. 56 - 74)voxpop88No ratings yet

- New Proposals - Journal of Marxism and Interdisciplinary Inquiry 2007, Vol. 1 No. 1 (May, 90 PP.)Document90 pagesNew Proposals - Journal of Marxism and Interdisciplinary Inquiry 2007, Vol. 1 No. 1 (May, 90 PP.)voxpop88No ratings yet

- Najam, Adil, David Runnalls & Mark Halle 2007 'Environment and Globalization - Five Propositions' (IISD) International Institute For Sustainable Development (48 PP.)Document54 pagesNajam, Adil, David Runnalls & Mark Halle 2007 'Environment and Globalization - Five Propositions' (IISD) International Institute For Sustainable Development (48 PP.)voxpop88No ratings yet

- New Proposals - Journal of Marxism and Interdisciplinary Inquiry 2007, Vol. 1 No. 1 (May, 90 PP.)Document90 pagesNew Proposals - Journal of Marxism and Interdisciplinary Inquiry 2007, Vol. 1 No. 1 (May, 90 PP.)voxpop88No ratings yet

- Nwanosike, Oba F. & Onije, Liverpool Eboh 2011 'Colonialism and Education' Proceedings of The International Conference On Teaching, Learning and Change, IATEL (Pp. 624 - 631)Document8 pagesNwanosike, Oba F. & Onije, Liverpool Eboh 2011 'Colonialism and Education' Proceedings of The International Conference On Teaching, Learning and Change, IATEL (Pp. 624 - 631)voxpop88No ratings yet

- ENG820 - Linguistics and The Study of LiteratureDocument130 pagesENG820 - Linguistics and The Study of LiteratureTaiwo AlawiyeNo ratings yet

- Synthesis of The StudyDocument2 pagesSynthesis of The StudyApril Grace EspinasNo ratings yet

- Tu Elt Conference Program 2017 May 15Document3 pagesTu Elt Conference Program 2017 May 15api-285624898No ratings yet

- Language TheoriesDocument2 pagesLanguage TheoriesmanilynNo ratings yet

- November 22 2021 Two Way Table of Specifications Workshop DIANADocument4 pagesNovember 22 2021 Two Way Table of Specifications Workshop DIANADhave Guibone Dela CruzNo ratings yet

- Module 1 - Part 1 1Document1 pageModule 1 - Part 1 1api-512818325No ratings yet

- CV Resume Hans LeijströmDocument1 pageCV Resume Hans LeijströmHans LeijströmNo ratings yet

- CHATSUMI - Score and PartsDocument2 pagesCHATSUMI - Score and PartsisadockNo ratings yet

- Word Study Schedule 2018-2019Document1 pageWord Study Schedule 2018-2019api-233429070No ratings yet

- 23KhudA04 PDFDocument477 pages23KhudA04 PDFzeldasaNo ratings yet

- Infinitive and GerundDocument3 pagesInfinitive and GerundJusep Del Valle Marín MorontaNo ratings yet

- Earliest Dutch Visits To Ceylon 0 PDFDocument50 pagesEarliest Dutch Visits To Ceylon 0 PDFSzehonNo ratings yet

- Primer Tema de InglesDocument85 pagesPrimer Tema de InglesAleja OcampoNo ratings yet

- CRLA EoSY G2 TagalogScoresheetDocument7 pagesCRLA EoSY G2 TagalogScoresheetSittie Shajara Amie BalindongNo ratings yet

- Final - Free Guide - Step Up Your Learning 9-19 PDFDocument13 pagesFinal - Free Guide - Step Up Your Learning 9-19 PDFSushant PrakashNo ratings yet

- ANT308 Answer Key 9Document5 pagesANT308 Answer Key 9DharmabatNo ratings yet

- Word FormationDocument5 pagesWord FormationAddi MuhammadNo ratings yet

- Clause AdverbDocument2 pagesClause AdverbAmalia Novita SariNo ratings yet

- Simcat 108 VaDocument28 pagesSimcat 108 VaAnonymous 20No ratings yet

- Excel VBA Programming - With ... End WithDocument2 pagesExcel VBA Programming - With ... End WithhugomolinaNo ratings yet

- Keep It Classy With These 15 Fuck You Quotes YourTango PDFDocument1 pageKeep It Classy With These 15 Fuck You Quotes YourTango PDFSusu SusuNo ratings yet

- Traveller Elementary - Test 2Document2 pagesTraveller Elementary - Test 2mppetra15No ratings yet

- 10th English Matric Model Question PaperDocument8 pages10th English Matric Model Question Papersahajeevi2307No ratings yet

- Niveles de Examen ResumenDocument14 pagesNiveles de Examen ResumenMili LopezNo ratings yet

- THE GENRES AND-WPS OfficeDocument18 pagesTHE GENRES AND-WPS Officelloyd balinsuaNo ratings yet

- Matrikulasi Bahasa InggrisDocument5 pagesMatrikulasi Bahasa InggrisMr DAY DAYNo ratings yet

- OCJP SyllabusDocument7 pagesOCJP SyllabusumatechNo ratings yet