Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Great Battles Over Qumran

Uploaded by

MichaelCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The Great Battles Over Qumran

Uploaded by

MichaelCopyright:

Available Formats

The Great Battles Over Qumran AUTHO R:Florentino Garcia Martinez TITLE: The Great Battles Over Qumran

SOURCNear Eastern Archaeology 63 no3 E:125-30 S 2000 Since their discovery some fifty years ago, the Qumran manuscripts have been the object of both the public's curiosity and scientific research. Why -Where does the passion come from that urges so many researchers from various nationalities and different sensibilities to slave over thousands of little fragments salvaged from the bottom of caves to reveal their secrets At the very moment that the State of Israel was coming into being, after the catastrophe of the Holocaust, evidence from the desert appeared. It testified to the life and thought of those Jews who lived at a time when another event that would profoundly influence western thought was also being born--Christianity. That same period would also see the great transformation of biblical Judaism into what would become Rabbinic Judaism. Preliminary information hinted that an entire library of religious texts contemporary with the second Temple was being salvaged. Each piece bought from the Bedouin or discovered by archaeologists shed new light on this period. These documents had been written before that period, and they were all preserved in their original language, that is to say, they were free from the influences of later orthodoxies. These documents held the promise of capturing the very moment of the great transformations of the religious thought of that far distant era, which had remained enigmatic until then. And since these manuscripts had been written before the process that fixed the sacred texts of the two great religions, they would also allow us to understand why certain writings were chosen over others, how the sacred text had

been established, how the Canon of the Bible had been formed. In effect, these manuscripts allowed the rewriting of the religious thought of the West because they could enable us to rediscover the sources of Christianity and recover original Judaism before the catastrophe. And for the state that was about to be born after so many centuries as the heir of ancient Israel, what better gift than these direct witnesses to the period before the destruction of the Jewish state by the Romans[Graphic Character Omitted] It is not astonishing then, given the extent of the risks being taken, that the history of Qumran research in these last fifty years reads like a succession of battles among scholars--a war with few rules. THE DATE OF THE MANUSCRIPTS The question of the authenticity of the manuscripts purchased from the Bedouin was quickly settled. The Sapira Affair was still too fresh to allow these manuscripts to be received without suspicion. (Sapira was an antiquities dealer from Jerusalem who had very nearly succeeded in selling a false biblical manuscript to the British Museum. He committed suicide when the hoax was discovered). Still, from the first excavations in Cave 1 in 1951, the proof of authenticity was quickly found. Scientifically controlled archaeological research led to the discovery of a few fragments coming from the same manuscripts as those bought from the Bedouin. This proved the authenticity of the purchased pieces. The battle of the dating, on the other hand, took longer to win. Very soon, an initial proof of global antiquity had been furnished, determining the age of the ceramic jars, oil lamps, and other objects found with the manuscripts. Carbon 14 analyses of the organic residues of the Qumran ruins and of the cloth in which certain documents were wrapped added to the proof. The manuscripts themselves were too precious to be submitted to this kind of analysis, which would have destroyed them. Their dating relied mainly on paleographic analysis, the precision of which was contested by a number of scholars. Only after 1987, with the development of new

spectrometric analysis requiring only a very small specimen, were new tests undertaken. The tests made by laboratories in Zurich and Tel Aviv in 1991 and by the University of Arizona in 1994 on more than fifty manuscripts confirmed precisely the dates proposed by paleographers like Frank Moore Cross, and proved beyond a doubt the age of the manuscripts. They had all been copied before the destruction of Jerusalem by the Romans, and the great majority originated in the second and first centuries BCE. WHO WROTE THEM? A longer battle--and one that has not yet been won--has to do with the origin of the manuscripts. Many preliminary associations (with the medieval Karaites, the Zealots, even with the Judeo-Christians) were definitively abandoned once the dating of the manuscripts proved them to be incompatible. Certain proponents of the association with Christian groups (such as R. Eisenman or B. Thiering) continue to promote their thesis--with more imagination than scientific rigor. The evidence, however, is indisputable. The historical setting of the protagonists of the events in the Qumran manuscripts is not that of the revolt against Rome in the first century of the Christian era, but of the second and first century BCE. The pioneering work of Dupont-Sommer and other scholars of the 1950s had tipped the scales in favor of the Essenes. They were the Jewish group with which the Qumran community had the greatest affinity. This research had established a series of parallels between the descriptions of the Essenes by classical authors (such as the Jewish historian Flavius Josephus and the Jewish philosopher Philo of Alexandria) and the characteristic elements of the community described in the manuscripts. The strength of the argument was such that this Essene hypothesis was practically considered dogma for almost thirty years, and still remains the most widely held today. But this hypothesis, which explains the facts brought to light by the first published manuscripts, especially those from Cave 1, does not suffice to explain additional information acquired since the discovery of Cave 4, with its great

diversity of manuscripts. Norman Golb of the University of Chicago attempts to solve the problem by disassociating all the manuscripts from any connection to the Qumran ruins (which he identifies as a fortress) and from theQumran community (whose existence he denies). For him, the manuscripts would have come from various libraries in Jerusalem and would have been placed at the site for security reasons as the Roman armies advanced. They would thus have preserved the writings of all the currents of thought during the period of the Second Temple. This interpretation brings up a series of insoluble difficulties and has, with good reason, been rejected by the great majority of scholars. Qumran is not a fortress, and the type of construction does not at all resemble the Hasmonean or Herodian fortresses of the region. The relationship between the caves (especially Cave 4) and the Qumran ruins has been proven by archaeology. The various caves contain the same type of manuscripts, often the same compositions, and copied by the same scribes. Despite the real diversity of the contents of the manuscripts, there is not a single one among them that can be identified as a work of the Pharisees, the most powerful and largest group in Judaism at the time. L. Schiffman has underlined forcefully the affinity of certain legal prescriptions found in the documents in Cave 4 with the halakhah of the Sadducees. He then proposes a Sadducean origin for the community rather than an Essenian one. The community would have been founded by dissident Sadducee priests, in disagreement with the way the ritual was being celebrated in the Temple of Jerusalem. These affinities, real but very rare, and limited to the domain of purification rituals and halakhah, do not explain other much more abundant halakhic positions that are not Sadducean. Nor do they explain the elements of community organization that appear in the writings of the Qumran community. They are also contradicted by certain theological ideas in the manuscripts, such as the belief in predestination, and in angels, explicitly denied by the Sadducees according to Flavius Josephus.

In my opinion, the hypothesis that allows for the best explanation while respecting the facts known today, is the one called the "Grningen hypothesis." It distinguishes clearly the origins of the Essene community from those of the Qumran community. The origins of the Essene community are to be found in the apocalyptical traditions of Palestine in the third and second centuries BCE, while the origins of theQumran community are found within the Essene movement toward the end of the second century BCE. The community would have come into being as the result of a schism within the movement, and the protagonist of this schism would be the one the texts call the "Teacher of Righteousness." A small group of faithful followers, among them a good number of priests, would have followed him. The reasons for the break, such as they appear in the Qumran texts, were, on the one hand, the interpretation of particular norms of the Torah regarding the calendar, the Temple, and the Holy City, and the norms of purity concerning the cult, the persons, and the objects. On the other hand, there was a strong eschatological expectation in which the present is seen as the "end of days." This hypothesis allows one to explain the numerous Essene elements in the Qumran texts as well as the numerous differences in community organization, in interpretation of the biblical text, and of the halakhah and theology. WHO HAS ACCESS TO THE MANUSCRIPTS? The last important battle was fought over who would have free access to all the material. The controversy just enumerated has taken place within the specialized arena of academic publications. This last battle was fought on the pages of popular magazines. It concerns essentially the material found in Cave 4 and was resolved only recently. On October 21, 1991, the archaeological authorities of Israel decided to give free access to all the manuscripts, including those not yet edited. This decision became inevitable after the one taken by the Huntington Library, on September 22 of the same year, to place copies of the manuscripts in its possession at the disposal of the public. This decision came after the publication in the USA, also in

1991, of a "pirate" edition of the majority of the photographs of the manuscripts. The results of the Israeli decision were: 1. the publication in 1993 of a complete microfiche edition of all the photographs of the manuscripts (and in a CD-ROM in 1997) and, 2. the acceleration of the publication of texts in the official series Discoveries in the Judaean Desert. No fewer than seventeen volumes have been published in the last six years (1994-1999) as opposed to seven in the previous twenty-seven years of research (1955-1982). To understand what is at stake in this last battle, we need to clarify the question of property rights. A fundamental archaeological principle in the Middle East has been that archaeological finds should be shared, after negotiations, between the State and the institution doing and financing the research. This principle was applied to the excavations at Qumran and the caves by the Jordanian Department of Archaeology, the Palestine Archaeological Museum (PAM), and the French Biblical and Archaeological School in Jerusalem (EBAF). It was also applied to the manuscripts bought from the Bedouin by the PAM and the EBAF. However, to make these purchases, the PAM and the EBAF had solicited funds from institutions of various countries such as the Vatican, France, Germany, the Netherlands, Great Britain, and the United States. In return, a proportional part of the manuscripts purchased with these funds became the property of these institutions and, after their publication, should have been transferred to them. That is why, according to these agreements, the finds from Cave 1 are dispersed today, partly in the Amman Museum, partly in the PAM, and partly in the National Library of France. That also explains why the Pesher of Nahum, found in Cave 4 and published in 1968, is in the library of the University of Heidelberg, and the Foolish Woman is at the University of Chicago. For its part, the government of Jordan declared in 1961 that all the manuscripts coming from Qumranand still found at the PAM were national property. Jordan also prohibited them from leaving the country. In exchange, Jordan gave the

institutions that were proprietors exclusive publication rights to the materials. These rights were conferred to the international team formed by the researchers sent to Jerusalem by the collaborating institutions, with the goal of preparing the publication of the manuscripts they owned. In 1966, Jordan nationalized the PAM which, like the rest of east Jerusalem, fell into Israeli hands during the Six-Day War. Since then, the Israeli archaeological authorities have administered the PAM and guaranteed the rights assigned previously, including the exclusive rights to publication of theQumran manuscripts. The controversy over exclusive publication rights was the result of previous rights of ownership that restricted access to the unpublished manuscripts to the international team of researchers charged with their publication. Public impatience with the length of time it was taking to publish the texts, the frustration of certain researchers for not having access to certain manuscripts whose existence was well-known, and a press campaign well-orchestrated by Biblical Archeology Review all combined finally to convince the Israeli archaeological authorities to authorize free access to all the manuscripts. The results of this decision were not long in coming. For the first time in fifty years, more or less complete translations of all the manuscripts were published in several languages. This offers a general view of the extraordinary library accumulated by the Qumran community during the two centuries of its existence. It is true that no one can claim that we have the entire library--our knowledge will always be limited and partial. But the recent availability of all the salvaged manuscripts gives us a general view and a new look at the Qumran texts, including those already known for some time. This overview has already changed the perspective with which we now read the sectarian texts, the most characteristic of theQumran group. And this has also changed the relative weight of the sectarian writings in relation to the whole collection. A SECTARIAN IDEOLOGY? The apocalyptic elements found in the sectarian writings

are fundamental to understanding theQumran community. The idea that the universe and humanity were created according to a predestined divine plan, the idea of the division of the world and of each human heart into two opposing factions, Light and Darkness, the idea of the fierce battle in which two forces are opposed in the course of history, and that of the final victory of the forces of good--all continue to define the ideological horizons of the community as well as its daily life. These may be seen in the awareness of election, separation from the rest of the people, break with the rites of the Temple, and preparation for the final battle. But recently available texts show clearly that the concrete application of the Law according to the particular exegesis of the community is even more important than eschatology in the life of the group, and that observance of the Law is truly at the center of the community life. In the majority of the sectarian texts, the legal sections are longer and carry more weight than the apocalyptic sections. At Qumran, as in Judaism generally, the halakhah is more important than the theology. The proportion of the texts originating in the community, and those that demonstrate no sectarian characteristics, is now changed. Before this, one could divide the manuscripts into two large categories, biblical manuscripts and Essene or Qumran texts (and possibly a small collection of texts of uncertain attribution). We now know that more than a third of the recovered manuscripts contain no elements that would allow us to define their content as sectarian. This proportion cannot easily be attributed to accidents of transmission. These texts, which are designated as "apocrypha and pseudo-epigraphic" or more generally "parabiblical" literature, were completely unknown except for a few rare exceptions. They present an astonishing richness and variety of thought. They prolong several lines of the biblical tradition, including the wisdom tradition, which is now amply represented by several "wisdom texts." They anticipate several ideas that were thought to be developments of later Judaism, or even Christianity. This collection of non-sectarian writings proves that

the Qumran community is heir to a much richer and more varied tradition than had been imagined. It also shows that sectarian ideology is only a part of Qumran thought. Total access to all the texts helps us discover a library that appears to be of a very particular kind. It is primarily a collection of religious literature, most of which, sectarian and non-sectarian, may be considered biblical interpretation. But this library is far from being a collection assembled by chance. The absence of certain writings done during this period, such as 1 Maccabees and the Psalms of Solomon, and the complete absence of works containing ideas opposed to those of Qumran thought (notably the ideas of the Pharisees), proves that this library does not represent the total picture of Judaism of the period. Rather, it rightly belongs to the Qumran community. The importance of nonsectarian writings in the collection also proves that the Qumran community was a less isolated and marginal phenomenon than originally believed. The study of the precise relationships between the sectarian and nonsectarian texts, as well as their relation to the biblical texts, still has to be done. WHAT ARE THE PROSPECTS FOR RESEARCH? After fifty years, Qumran research is really still beginning. What we have found in the Qumranmanuscripts has already completely transformed our way of considering the growth and development of the biblical text and the establishment of the "canonical" collections. The relationship between the para-biblical texts and the sectarian texts must still be clarified. The real work of interpretation could not begin until all the evidence in each work had been published. They are often very different from one another. A detailed study of the para-biblical compositions will show the richness and the variety of Jewish thought in the period of the Second Temple. A study of the transformations revealed by the various copies of the sectarian texts will tell us about the evolution of thought and the modifications of the structures of theQumran sect. It will also show us its relationship with the political powers of Jerusalem and the others groups within Judaism.

But the history of the community and the sociological support of the texts will not completely be disclosed until the archaeological material has been published fully. Since the preliminary report of the findings by Roland de Vaux, necessarily succinct and limited, and his brilliant synthesis of the results, we are still waiting for the integral publication of the stratigraphy and material assemblages of ceramics, coins, textiles, and glass. Only one volume with photographs and excerpts from the de Vaux notes has been released to the public. Without the archaeological finds, the study of the texts does not have critical historical foundation. The recent publication of a solar clock is a good example of the information that certain objects can provide (see page 166). The complete publication of the excavations of Khirbeh, the caves and cemeteries, is still the missing element for the appreciation of the "greatest archaeological discovery of the twentieth century." ADDED MATERIAL By Florentino Garcia Martinez Director of the Qumran Institute, University of Grningen (Holland). Translation by Claude Grenache, A.A. The site of Qumran, aerial view from the south. In the foreground, the wadi Qumran runs toward the Dead Sea. Above hang the steep cliffs with numerous caves where the manuscripts were discovered, and above them, on the terrace, lies Khirbet Qumran, the ruins of the community establishment. John Starcky working in Cave 4, which was explored in September 1952 and revealed the ridtest deposit of scrolls. Father Starcky was in charge of editing for the first team of decipherers. After his death in 1988, this lot of manuscripts went to mile Puech. MdB / Totemico Roland de Vaux reading a plan of the excavations. Alexander Maurer, a researcher with the German team of Qumran specialists under the direction of H. Stegemann, working here on the reconstruction of the manuscript 4Q511. KARAITES Dissidents from Judaism after the schism that began

around the eighth century CF. Karaism is essentially distinguished from rabbinical Judaism by the rejection of oral law represented by the Talmud. ZEALOTS Members of a Jewish revolutionary group of the first century CE. They were involved in flerce massacres during the first Jewish revolt against the Roman empire. HALAKHAH ("the way") Rabbinical jurisprudence teaching the people proper conduct. SADDUCEES An aristocratic political-rehigious group in Judaism, formed in the second century BCE and lasting until the first century CE. Approaching the power of the Pharisees and openly rivaling them, they strictly respected the written Law, refusing to believe in the immortality of the soul and in the resurrection. THE PUBLICATION OF THE QUMRAN AND A"N FESHKHA EXCAVATIONS, ENGLISH EDITION By Stephen 1. Plann, Center for the Study of Early Christianity, Jerusalem. Translation by Claude Grenache, A.A. The planned publication of Father Roland de Vaux's archive begins and ends with his field notes. Their excellent transcription by Jean-Baptiste Humbert (along with photographs and diagrams) was published with Alain Chambon under the title "Fouilles de Khirbet Qumran et Ain Feshkha" in the Series Archaeologica, 1 of Novum Testamentum et Orbis Antiquus, Fribourg, Switzerland, 1994. They constitute the point of departure for all future debates on the archaeology of Qumran. The English annotated translation in preparation will place this important data at the disposal of the English-speaking public for the first time. This edition will comprise: 1. The plans of the site (with the addition of levels); 2. A literal but annotated translation of the French edition, carefully compared with the corrected typewritten original report by de Vaux: 3. Notes clarifying the meaning of the text and the

perspectives it opens, and the inventory numbers of the photographs and plates of the French edition and other sources, well-known for their fine illustrations: 4. Inventory of the augmented material including: the spot on the site where each object was found; corrections based on the cataloguing of the objects; the publication references and the photo catalogue numbers in the Palestine Archaeological Museum (PAM); coded pottery types with references to the chronology of Palestinian ceramics; the identification of the historical periods; 5. Improved numismatic inventories thanks to the identification proposed by Augustus Spijkerman (following the numbers of the existing catalogue); 6. A classification of the ceramic types (with drawings) adapted from the first work done by de Vaux. The formulation of the transcriptions by Humbert has been carefully preserved. In addition, an Addenda and Corrigenda will accompany the volume, which will include a list of corrections made for typographical errors in the French volume and the mention of significant additions and changes to the sections. Additional suggestions by the English editor concerning the opinions of de Vaux of the transcriptions of Humbert will be presented in footnotes. In addition, references to articles in Revue biblique, and to the inventories of objects and photographs of the PAM have been added to the Englishedition. This new volume is meant to complement the first and future volumes of the Series. NTOA Series Archaeologica 1B, in pieparation. English annotated translation from the field notes of Futher Roland de Vaux. KHIRBEH Literally, the "place of ruins" in Arabic. It is written with a final "t" when it is followed by a descriptive complement (as in Khirbet Qumran). It designates an archaeological site. Source: Near Eastern Archaeology, September 2000, Vol. 63 Issue 3, p125, 6p

You might also like

- JTS Library Cataloge of Rabbinic Mss. (Vol. 10)Document120 pagesJTS Library Cataloge of Rabbinic Mss. (Vol. 10)MichaelNo ratings yet

- The BRIGANCE Diagnostic Life Skills InventoryDocument5 pagesThe BRIGANCE Diagnostic Life Skills InventoryMichael0% (2)

- Three Fragments of A Personalized Magical HandbookDocument36 pagesThree Fragments of A Personalized Magical HandbookMichaelNo ratings yet

- The Scroll of The HasmoneansDocument7 pagesThe Scroll of The HasmoneansMichaelNo ratings yet

- Description of Civitates Orbis TerrarumDocument2 pagesDescription of Civitates Orbis TerrarumMichaelNo ratings yet

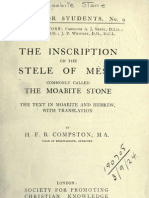

- The Moabite StoneDocument16 pagesThe Moabite StoneMichaelNo ratings yet

- Medicine in The TalmudDocument2 pagesMedicine in The TalmudMichaelNo ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5795)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Excavations of JerichoDocument4 pagesThe Excavations of JerichoJay SmithNo ratings yet

- Troyer Names of GodDocument35 pagesTroyer Names of GodcadkinsjrNo ratings yet

- How To Succeed at Being Yoursel - Joyce MeyerDocument307 pagesHow To Succeed at Being Yoursel - Joyce MeyerDhugo Lemi100% (2)

- Priesthood of MelchizedekDocument4 pagesPriesthood of Melchizedekdikoalam100% (1)

- The Origin of The Book of Zechariah Author(s) : T. K. Cheyne Source: The Jewish Quarterly Review, Vol. 1, No. 1 (Oct., 1888), Pp. 76-83 Published By: Stable URL: Accessed: 19/05/2014 07:13Document9 pagesThe Origin of The Book of Zechariah Author(s) : T. K. Cheyne Source: The Jewish Quarterly Review, Vol. 1, No. 1 (Oct., 1888), Pp. 76-83 Published By: Stable URL: Accessed: 19/05/2014 07:13Ana CicadaNo ratings yet

- May The Daughter of A Gentile and A Jew Marry A KoheinDocument30 pagesMay The Daughter of A Gentile and A Jew Marry A Koheinhirhurim100% (1)

- Bible Reading Plan-Chron NT 100 Days A4Document1 pageBible Reading Plan-Chron NT 100 Days A4RobinkungNo ratings yet

- Akhenaton PDFDocument16 pagesAkhenaton PDFArtur FelisbertoNo ratings yet

- Shirat Hayam - Song of The Sea: Close and AcceptDocument2 pagesShirat Hayam - Song of The Sea: Close and AcceptTheop Ayodele0% (1)

- Six Warnings - Richard Owen Roberts - YouTube - EnglishDocument38 pagesSix Warnings - Richard Owen Roberts - YouTube - EnglishgraciayverdadcanadaNo ratings yet

- Incirli Trilingual InscriptionDocument34 pagesIncirli Trilingual InscriptionskaufmanhucNo ratings yet

- Handel Israel in Egypt Program NoteDocument2 pagesHandel Israel in Egypt Program NoteDan SannichNo ratings yet

- Christ, Our High Priest in Heaven - RB Gaffin - JR - 8ppDocument8 pagesChrist, Our High Priest in Heaven - RB Gaffin - JR - 8ppAlmir Macario BarrosNo ratings yet

- TX001027 1-Content - Salvation HistoryDocument5 pagesTX001027 1-Content - Salvation HistoryAxielNo ratings yet

- Characteristics of People of JannahDocument4 pagesCharacteristics of People of Jannahdian handayaniNo ratings yet

- 1 Thessalonians 2Document3 pages1 Thessalonians 2Crystal SamplesNo ratings yet

- Lilith The Woman of DisobidenceDocument14 pagesLilith The Woman of DisobidenceJack Brown50% (2)

- Merry Christmas or Happy Sabbath!Document3 pagesMerry Christmas or Happy Sabbath!SonofManNo ratings yet

- Bible TriviaDocument21 pagesBible TriviaRon MacasioNo ratings yet

- The Dua 'A (Prayer) of Prophet Muhammad (PBUH) in Ta'if BS Foad, MD 2017Document16 pagesThe Dua 'A (Prayer) of Prophet Muhammad (PBUH) in Ta'if BS Foad, MD 2017SYED IBRAHIMNo ratings yet

- Recognition Program ScriptDocument2 pagesRecognition Program ScriptMichael Stephen Gracias100% (2)

- Surah Al Infitar Chapter 82Document8 pagesSurah Al Infitar Chapter 82Naheed ChowdhuryNo ratings yet

- Abdi-The Case of The Daiva InscriptionDocument38 pagesAbdi-The Case of The Daiva InscriptionMadhav DeshpandeNo ratings yet

- New Jerusalem ProgramDocument16 pagesNew Jerusalem ProgramTheater JNo ratings yet

- Psalms Book 4Document11 pagesPsalms Book 4Alan67% (3)

- The Name Samael Aun WeorDocument14 pagesThe Name Samael Aun WeorLaron Clark100% (3)

- Ce Intro To The Bible Final Exam 2020 Grade11Document2 pagesCe Intro To The Bible Final Exam 2020 Grade11elmerdlpNo ratings yet

- News & Notes: As The Scrolls Arrive in ChicaDocument24 pagesNews & Notes: As The Scrolls Arrive in ChicaGiaNo ratings yet

- Judaism 101 EbookDocument80 pagesJudaism 101 Ebookkrataios100% (1)

- The Power of Knowing God: Precept Ministries InternationalDocument5 pagesThe Power of Knowing God: Precept Ministries InternationalLife BooksNo ratings yet