Professional Documents

Culture Documents

WO Rker Odwo: Toda Y' S

Uploaded by

Rocio MtzOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

WO Rker Odwo: Toda Y' S

Uploaded by

Rocio MtzCopyright:

Available Formats

TODA

WO

Y

RKER

S

ODWO

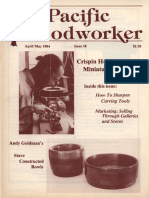

Americas leading woodworking authority

Brought to you by

1990 - Issues 7-12

January/February

Volume 2, Number 1

March/April

Volume 2, Number 2

May/June

Volume 2, Number 3

July/August

Volume 2, Number 4

September/October

Volume 2, Number 5

November/December

Volume 2, Number 6

Go to

Disc Homepage

Go to

Content Search

Issue 11 $3.95

TI PS

Ii ,.) L \ ~ i

WOODWORKER"

PROJECTS, TIPS AND TECHNIQUES

8 Barrister's Bookcase 2 Joday's Wood

By T. Martin Daughenbaugh A standout in the forest is valued for

its subtle presence in the shop. A classic piece of furniture is

matched up with modern hardware

for outstanding results.

3 On the Level

Our first survey results.

4 Tricks of the Trade

15 Spinning String Top

By Craig Lossing

Here's a beautiful turning project

that you can spin out in a day.

16 Kid's Step Stool

By Bill Johnson

Readers share their shop shortcuts.

5 Hardware Hints

Install Accuride's flipper slides.

6 Techniques

The first step to veneering success.

20 Today's Shop

Part 2 on sharpening. This time

Roger Cliffe covers honing.

21 What's in Store

The kids will line up to brush their

teeth once you've completed this

weekend project.

Hugh Foster reviews the Veritas

Stone Pond.

22 Yesterday's Woodworker

Find the right hand planes for your

shop with Michael Dunbar's help.

18 "In Out" Desk Tray

By David Ashe

This simple one day project unveils

an easy approach to working with

inlay banding.

r TODAY'S WOOD

Birch (Betula alleghaniensis)

Birch is unquestionably a species of contradiction. The

white bark of birch boldly stands out from all other

trees in the forest, but in the shop the species has one

of the most subtle appearances among commonly used

domestic timbers. Complementing its whitish color, a

faint pattern sweeps across this closed grained, evenly

textured wood; a desirable characteristic when the pro-

ject's design needs to dominate the wood's appearance.

In the shop, birch works well with both hand and

power tools, particularly for a wood that falls between

oak (harder) and cherry (softer) in hardness. It saws,

planes and turns well with relatively little tearing and

splintering. Birch experiences significant shrinkage

while drying, but once properly seasoned offers good

stability and resists warping and twisting.

23 Finishing Thoughts

The Clean Air Act is paving the

way for new water based lacquers.

24 Reader's Gallery

Alaskan woodworkers create works

of art with an indigenous species.

Birch is a suitable choice for structurally critical

pieces in furniture because it compares to oak and

maple in strength, and beats both of those species quite

significantly when it comes to shock resistance. If

you're choosing wood for a bending project, birch

offers excellent elasticity, somewhat similar to ash.

However, keep in mind that outdoor applications

are simply out of the question for this species

because it is highly susceptible to decay.

Birch is unequalled when it

comes to accepting a clear varnish

or polyurethane finish, but is

much less suitable for staining

because of its tendency

to become blotchy.

SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 1990

Vol. 2, No.5 (Issue 11)

LARRY N. STOIA1illN

Editor

JOHN IillLLIHER

Art Director

CHRIS INMAN

Associate Editor

STEVE HINDERAIillR

Associate Art Director

NANCY EGGERT

Production Manager

JEFF JACOBSON

Technical Illustrator

GORDON HANSON

Copy Editor

ANN JACKSON

Publisher

JIM EBNER

Director of Ma rketillg

VAL E. GERSTING

Circulation Director

NORTON ROCKLER

RICK WHITE

STEVE KROHMER

Editorial Advisors

ROGER W CLIFFE

SPENCER H. CONE II

BRUCE KIEFFER

JERRY T TERHARK

COlltributing Editors

Today's Woodworker, (USPS 147-614) is

published bimonthly (January, March, May,

July, September, November) for $23.70

per year by Rockier Press, 21801 Industrial

Blvd., Rogers , MN 55374-0044. Second

class postage paid at Rogers , MN and

additional mailing offices.

POSTMASTER: Send address changes to

Today's Woodworker, PO Box 6782, Syra-

cuse NY 13217-9916.

One year subscription price, $23.70 (U.S.

and possessions); $28.95 (U.S. currency

-other countries). Single copy price,

$3.95; (other countries, $5.50, U.S. curren-

cy). Send new subscriptions to Circulation

Dept. , Today's Woodworker, PO Box 6782,

Syracuse NY 13217-9916. Subscribers are

welcome to submit project proposals, tips

and techniques to the editor, Today's

Woodworker, Box 44, Rogers, MN 55374.

For purposes of clarity, illustrations and

photos are sometimes shown without prop-

er guards in place. Today's Woodworker

recommends following ALL safety precau-

tions while in the shop.

Today' s Woodworker is a trademark of

Rockier Press.

Copyright 1990, by Rockier Press.

All rights reserved.

ISSN: 1041 -8113

.. ----__ ON THE LEVEL

Survey Says!

In an effort to belter serve our readers, These projects, it seems, are filed away to

Today's Woodworker recently started a be completed at a later date. In this issue,

survey program. Shortly after each issue we' re presenting projects based on what

is mailed, 200 subscribers receive a sur- our surveys have told us -a difficult pro-

vey form and are asked to rate each pro- ject that can be worked on slowly (or

ject and department in the new issue and later) , and three easier proj ects that can

make suggestions for future issues. be completed in one weekend.

We've now completed three of these Other results include much praise for

surveys and are starting to get a snapshot passing on adverti sing, solid backing for

of what our readers want. At the top of the our departments and numerous requests

list of suggestions is "more projects that for a chest of drawers, now planned for

can be completed in a single weekend. " the next issue. Please remember, even if

Coupled with this suggestion is the curi- you don't get a survey, we still want to

ous fact that our most diffi cult projects hear from you. LA,. ~ /

have been rated the highest in each issue. ,,{<II / IV. r J l f l ~

I have only received two issues of

Today's Woodworker so far and have

enjoyed both of them. I am looking for-

ward to future issues.

Enclosed please find a picture (at

right) of the porch glider I just finished,

using the plans in your May/June 1990

issue. The plans were modified to use

less wood (aromatic cedar). I used 5/4,

3/4, and 3/8. It features all mortise and

tenon joints.

Paul Al mburg

Malta, Illinois

I 'm writing to

show you a pro-

ject that we did

from your maga-

zine. My hus-

band and I work

together and have

started a few of

your projects.

We made two

of the stools from

the March/ April

1990 issue -one

for my neighbor

and one for me. I made mine out of

some scrap pine and my neighbor's out

of aspen. We won't ever use that wood

again! YukI! I really like mine and get

lots of compliments on it.

We did the back brace a little differ-

ent. I have two boys and your design

wouldn't stand up to the abuse on it. We

do enjoy the magazine a lot.

We plan to build the easel that was

featured in the Sept/Oct 1989 issue. I

would like to see more designs for chil-

dren's rooms. I've heard about pencil

beds. At $500.00 for a twin size frame,

they are quite costly to buy I'd like to

see this featured or something like it.

Debra and I<ris Heskin

Norwich, North Dakota

It 's really nice, for a change, to read an

arti cle on woodworking by someone

who realizes that the main purpose of

wood is not for use in the fireplace. My

only complaint was that some issues

were received wet or dog- eared. I

called and was assured that these

issues would be replaced at no charge.

Thanks, and keep up the good wort<.

Robert D. Bryson

Willow Grove, Pennsylvania

Three months ago I decided to make

the workbench featured in your Jan/Feb

1990 issue. I immediately wrote to the

Cambridge Tool Company in Canada

about their vices. I received no

response and have since heard that

they went bankrupt. I have the base of

the workbench all finished and I hate to

start the top till I know something defi-

nite about the vices. Is there a U.S.

company that makes a similar alterna-

tive? I enjoy your magazine very much.

Dale Watson

Coburn, Pennsylvania

Today's Woodworke1' respollds: Chec/l with

the supplie1's listed on page 24 of each

issue. hi particular, The Woodworllers'

St01'e 110W atnies top quality Hirsch vices

tliat are a suitable replacement.

TODAY'S WOODWORKER SEPTEMBER/ OCTOBER 1990

TRICKS OF THE TRADE

Creative Jigs For Power Tools

sliding bolt

Radial Arm Saw Accuracy

I've come up with a jig that will

improve the accuracy of any radial

arm saw. These saws typically cut

well at 0, but a miter cut can be easi-

ly off by a degree. My adjustable

fence is 1/2" x 1

1

/4" x 28" and its front

is jointed to ensure a straight edge. I

used a small straight bit in the router

to make the slot in the fence and in

the auxiliary table. Make the cleat the

width of your existing fence (for my

Sears model this was 3/4" x 11k" x

28

11

) and make the table about 3/4" x

20" X 18" (I used 3/4" cabinet grade

plywood). Cut a dado on the bottom

of the table so the wingnut's bolt has

room to slide. Assemble the three

parts of this jig, remove your saw's

fence, and clamp the cleat in place.

Make a trial cut along the right side

of the auxiliary table. Using a machin-

ist's protractor against the edge of

this saw cut and the adjustable fence,

layout lines for your most often cut

angles on a piece of tape.

John C. S. Heffner

Huntersville, North Carolina

File off

Countersink

Bandsaw Blade Bench Stops

I've been building work benches for

my grandchildren and have found

that sections of 1/2" wide bandsaw

Angles on

masking tape

blade (with the teeth filed off)

screwed to maple stock make great

bench stops. The spring-like curved

blade adds just enough tension to

keep the "dogs" in place.

Joe Randolph

Danbury, Wisconsin

Magnetic Push Stick

All my saw push sticks and blocks for

cutoffs have small magnets recessed

flush and epoxied in place. When I'm

done with a cut I just slap the push

stick or block onto the side of the

saw. The magnets keep them there.

Willis Clark

Boone, Louisiana

Burning Tool Revisited

While Don Kinnaman's accent burn-

ing tool (See "Tricks of the Trade",

page 5, in the Marchi April 1990

issue) will do a fine job of highlight-

ing, it also raises a red warning flag.

As long as the wire between the

two dowel handles is kept taut, it is

fully safe, but in inexperienced or

careless hands the potential for disas-

ter exists. If the wire becomes slack

and catches on the piece being

accented, you may end up with a

lethal winding or lashing of the tool,

and a maiming or loss of fingers.

My suggestion is to modify an old

hack saw frame instead of using the

two pieces of dowel to hold the wire.

The wire need not be tensioned, but

merely drawn snug.

Be sure

the "V"

shape

is close

to 9CJ'

A Dutchman's Repair

Kenneth Harlan

Lancaster, Ohio

While turning, an unexpected knot or

defect may suddenly appear on a

bead area of a spindle. This could

ruin an otherwise perfect job. A sim-

ple solution to this problem is to

install a dutchman repair in the defec-

tive area after the spindle has been

completely cut to shape.

Cut a V-shaped section out of the

turning to remove the defect, keeping

the angle close to 90. Now find a

piece of wood that matches the color

and grain of the area surrounding the

cutout, and cut it down until it's

slightly oversized. Plane the sides

tangent to one corner to fit into the V-

cutout (the V may also need fine tun-

ing for this fit). Once you have a good

fit, glue the repair piece into confor-

mity with the bead. Finally, with the

spindle turning in the lathe, sand the

entire piece to its finished shape.

Eric Black

Washington, D. C.

SEIYrEMBER/OcrOBER 1990 TO DAY'S WOODWORKER

f

3/8" shaft collar

with set screw

3-4d nail tips

.. r glued with epoxy

3/8" diameter rod

Duplicating Small Spindles

When I make a significant number of

small diameter spindles on a lathe, I

prefer to cut all the spindles to fin-

ished length before the lathe is used.

In addition, I prefer to have the holes

drilled at each end of the spindle to

accept dowels before any lathe turn-

ing is done. This way, I'm always sure

that every spindle is perfectly identi-

cal and accurate.

This requires the fabrication of a

small diameter live center which is

mounted in a lathe chuck. It also

requires a ball bearing dead center

with a tapered tip. The live center is

made from a 3" length of steel rod

3/8" in diameter, a 3/8" shaft collar,

and tips of three 4d finish nails. Sim-

ply drill three evenly spaced holes on

the flat side of the shaft collar approx-

imately 1/4" deep. The three holes

should be the size of the nails. Cut

the nails so that only the sharp tips

protrude when they are epoxy glued

into the shaft collar. Slide the shaft

collar onto the rod and tighten the set

screw. The steel rod centers itself in

the pre-drilled hole of the spindle

while the three nail tips effectively

drive the spindle for turning. The

tapered tip of the dead center will

automatically center itself in the pre-

drilled hole at the opposite end.

Richard Dorn

Oelwein, Iowa

(Please turn to page 7)

r HARDWARE HI NTS

Accuride's Flipper Door

Hardware

By Chris Inman

Installing flipper door hardware is

mostly a matter of accurately laying

out the various pieces and sticking

with 3/4" thick door stock. If you're

installing a frame and panel door, as

with the barrister bookshelf on page

8, remember that the 35mm holes

for the Blum hinges must fall solidly

within the door rail and not project

into the panel.

I always start my installations with

the mounting brackets for the

slides, first positioning the front

bracket (as shown below) and then

installing the slide to help position

the rear bracket. A #6 Vix bit is ideal

for drilling the pilot holes.

The length of the follower strip

should match the door width, and

the dadoes should be cut very pre-

cisely since their depth establishes

the size of the gap between the door

and the cabinet along the hinged

side. Lay the follower strip and the

door edge to edge in order to install

the Blum hinges. Draw a center line

down the dado and onto the door,

then drill the 35mm diameter cup

Install the brackets and the slides, following

the measurements. Next layout the Blum

hinge locations on the door and follower strip.

Once the door is machined, the follower strip

is installed and the hinges are coupled. The

hinge will allow adjustments in three

directions for aligning the door.

1/4" Depth

Mounting plate is

flush with front edge

of follower strip. / ~ n ~ ~

f

Flipper doors, like the ones used on the

Barrister Bookcase on page 8, are a terrific

way to keep a streamlined appearance on your

cabinets while concealing televisions or

other appliances.

,hole 1" from the door's edge. Now

secure the mounting plate in the

dado, centering it on the line, and

position the screw holes 11116'1 back

from the edge.

Mount the follower strip onto the

slide brackets, keeping the front

edges flush and then connect the

two hinge sections to join the door

to the slide assembly.

Cabinet

Follower

Strip

3/4" x 3"

Front Vi ew

Door

--

.. _____ TECHNIQUES

Veneering A Drawer Face

By Bruce Kieffer

Veneering is one of the

most challenging and inter-

esting aspects of wood-

working. In fact, many in

the field consider it an art

form. While there's a lot of

techniques to learn on the

road to mastering veneering,

there's always a starting point. In

the seminars I teach, I like to start

out by concentrating on a simple and

practical application. Let's say you

want to make a maple chest of draw-

ers. The front of this chest will be all

drawer faces, made to look like one

large flat plane. To give your chest a

decorative look you decide to make

the drawer faces out of birdseye

maple. Here's a situation where

veneering is the perfect solution.

You'll be doing the simplest form of

flat panel veneering, requiring no join-

ing or seaming and you probably have

most of the tools you need on hand.

Basically, a veneered drawer face

has a 3/4" industrial grade particle

board core edged with 1/4" thick solid

wood, and then covered on both sides

with glued on veneer. Whenever

you're working with veneer you must

remember that you have to end up

with a balanced panel. This means

that whatever is applied to one side of

the core is also applied to the other

side. In addition, the grain of the

veneer should run the same wayan

both sides of the core. To save on

costs, the hidden inside of the drawer

face can ' be veneered with a different

grade or species of veneer.

Having enough clamps on hand is

also critical. Your clamps should be

spaced at three to four inch intervals

on the entire surface of the core and

you should have some clamps on hand

with jaws that are deep enough to

reach and apply pressure to the center

of the core.

Almost any glue that's made for

bonding solid wood can be used for

veneering. I generally favor yellow car-

penters glue but will switch to white

glue (which dries slower) when

veneering larger surfaces. While some

FIGURE 1: Glue and clamp the solid edging to the

core, two sides at a time. The corners of the

edging can be mitered or overlapped.

FIGURE 2: Use a paint roller to spread the glue

evenly on the core and the back of the veneer.

woodworkers contend that contact

cement works fine and cuts down on

clamping requirements, my own expe-

rience has been that it doesn't offer

enough bonding strength to hold the

veneer down for an extended period

of time. .

Make Your Drawer Face

I generally make my drawers and

drawer faces as separate components.

When they're ready to be assembled,

I drill 3/8" holes through the fronts of

the drawers and attach the drawer

faces with screws and washers. The

3/8" holes allow for minor adjust-

ments and make it easy to align the

drawer faces in their openings.

Calculate the finished widths and

lengths of each drawer face and then

cut your particle board cores 1/2"

narrower and shorter to allow for the

Clamps at 3" to 4" intervals

Caul

FIGURE 3: Start clamping in the center of the core

and slowly work the pressure out toward the

edges. This method of clamping reduces the

possibility of trapped glue pockets.

FIGURE 4: Trim with a flush trimming bit with ball

bearing pilot. Rout backwards to reduce tear out.

1/ 4" thick solid edging. Cut the solid

edging 1/4" thick, 3/4" plus 1/32"

wide, and I" longer than the lengths

you need. You can miter the ends of

the edging or you can overlap them.

In either case, once this is done, glue

and clamp the edging to the core, as

shown in Figure 1. When the edging

is complete and the glue has dried

sand the edges flush with the core.

The next step in this process is to

rough cut the veneer. An inexpensive

tool known as a veneer saw works

best for this task. Layout the areas

on your veneer sheets where you will

cut out the pieces for the drawer

faces. Make sure to add at least I" in

length and width for overhang,

which will be trimmed off after the

veneer is glued in place. Carefully

guide the veneer saw against a

straightedge and cut the length, and

then the width of the veneer. Make

SEPTEMBER/ OCTOBER 1990 TODAY'S WOODWORKER

several light cutting passes with the

saw until you cut through the veneer.

Gluing and clamping the veneer to

its core is simple. I like to think of it

as creating a triple decker sandwich

with plenty of mayo. Each side of the

c?re is covered with glue, then one

side of each veneer piece is covered

with glue. These are positioned

against each other, followed by a sepa-

rator piece of newspaper, and finally a

caul to flatten the veneer and dis-

tribute the pressure from the clamps.

In this case, the cauls are 3/4" particle

board pieces cut to the same length

and width as the veneer. Do one draw-

er at a time, using a roller to spread

the glue, as shown in Figure 2.

. Start applying pressure by clamping

III the center of the drawer face and

working out. This eliminates the pos-

sibility of trapping any glue pockets in

the middle of the drawer face (See

Figure 3). Allow the glue to cure for

24 hours and then unclamp and sepa-

rate your sandwich.

Finish up your drawer by chucking

a flush trimming bit in the router and

trim off the overhanging veneer

edges, as shown in Figure 4. Routing

backwards, essentially pulling the

router toward you, will reduce the

chance of tear out. Finish sand the

drawer faces, check their fit, and

make any necessary adjustments.

Make sure to apply your finish equal-

ly to all surfaces of the drawer faces

to properly seal them and reduce the

chance of warping.

In the next installment on veneer-

ing, I'll cover splicing and joining

veneer for more advanced projects.

Until then, if you're interested in

more detailed information about

veneering, read the books "A Manual

of Veneering" by Paul Villard and

"Practical Veneering" by Charles H.

Hayward. Both should be available at

your local public library.

Bruce Kieffer is a professional wood-

worker and contributiong editor with

Today's Woodworker magazine.

TRICKS OF THE TRADE CONTI NUED

Raise bit

'---Jh:-.....----,- to desired

depth once

jig is in position.

"V" groove cut

almost through

Fluting Jig For the Router Table

The original oak columns on my

china cabinet were damaged beyond

repair, so I turned new columns on

the lathe, marking the base ends

with equally spaced radii while it

was still on the lathe. Then I used

the "V" groove jig pictured above on

a router table, which makes it easy

to flute a tapered column.

The pine jig with a 45 "V" groove

cut almost through holds the col-

umn with the lower surface parallel

to the table. Cleats across the ends

strengthen the jig and serve as a

stop. A thin piece of plywood fas-

tened to the cleat (with the edge in

line with the bottom of the "V")

serves as a guide and ensures even-

ly spaced flutes.

The column is placed in the jig

and the router table fence is set to

position a core box bit at the center

of the column. Raise the bit to the

desired depth. On our piece, the

flutes stopped 1" from the ends of

the column so a piece of masking

tape was placed on the fence to

mark starting and stopping points.

In use, the marked end of the col-

umn is placed against the plywood

guide with the index line even with

the edge. The router is then started

and one end of the column is low-

ered into the "V" and held down

while the jig is moved to the mask-

ing tape stop point. The rest of the

flutes are made in the same manner.

The flutes will all be the same depth

and have the same spacing.

The completed columns look like

they belong on the repaired china

cabinet. Straight columns can also

be made in the same manner.

Handy Oiler

Alice & Robert Tupper

Canton, South Dakota

A discarded plastic or glass medical

syringe makes an ideal "oiler" to

reach difficult spots when it is fitted

with an appropriate length of small

plastic tubing. If the tubing is large

enough it can be slipped over the

of If smaller tubing

IS required slip the tubing over a

large bore needle that has the bevel

ground off.

Several needles can be fitted with

tubing of different lengths to serve

specific oiling jobs.

Hugh F. Williamson

Tucson, Arizona

Today's Woodworker pays from

$20.00 (for a short tip) to $100.00

(for an elaborate technique) for all

Tricks of the Trade published. Send

yours to Today's Woodworker,

Dept. TIT, Rogers, MN 55374-0044.

BUILD A BARRISTER'S

BOOKCASE

The author needed a dust free environment for his collection of almost

600 record albums. The classic look of the Barrister 's bookshelf

was appealing, but would it carry the load?

By T Martin Daughenbaugh

T

he practical appeal of the

barrister's bookcase has

always been focused on one

key benefit -it provides a

completely dust-free environment for

fine books and treasured art objects.

Add record albums to the list,

because that's what I really had in

mind when I designed this project. As

a result, it's a little larger and sturdier

than the standard law office version.

Two critical design changes were

necessary to make this project work

for its intended application. First, I

had to beef up the shelves with web

frames to avoid the inevitable sagging

that would otherwise occur. That

meant heavier lines throughout to

keep everything to scale. Second, I

was determined to avoid the double

pin or weight mechanisms typically

employed with this type of furniture.

The ones I've seen tend to stick or

bind, and I wanted easy access and

smooth operation. To get this, I

picked Accuride ball bearing flipper

door slides. The ones I ordered come

coupled with high quality Blum

hinges and are practically invisible

once the doors are installed.

A Quick Overview

The author used

various routing

profiles to achieve a

distinctive look.

Notice how the

stopped roundover

used on the sides

(below) is repeated on

the front door frames,

shown above.

If you have a tablesaw and a good

plunge router in your shop, you're

pretty well equipped to take on this

project. A drill press for the mortise

and tenon joinery helps, but it's not

absolutely necessary. And if you don't

have a jointer, you'll have to visit a

woodworker who does, since there's

a considerable amount of panel con-

struction and you must have clean,

straight edges. You'll be doing mor-

tise and tenon joinery, miter joinery,

and you'll be cutting some precision

stop dadoes. If you want to duplicate

my design exactly, you'll also need a

pretty good variety of router bits,

including the slot cutting bit, panel

raising bit, roundover bits, straight

bit, beading bit and a Roman ogee bit.

The shelves are made of 1/2" wal-

nut plywood with a 3/4" solid walnut

web frame glued to the underside,

giving a total thickness of 11/4"; strong

SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 1990 TODAY'S WOODWORKER

..

The six panels for the two sides are cut from two

larger panels to provide some grain continuity.

Be sure to carefully joint the edges so they match

up nicely and cut the six pieces 40" long so you

have a slight margin for error when you go to cut

the panels down to their exact length.

enough to carry a full load of albums.

The solid walnut top of this Barris-

ter's bookcase is also supported by a

web frame, but here the frame is

used for dimensional continuity

instead of load bearing require-

ments. Finally, the three doors are

designed with 2" wide frames that

are mitered and employ small

splines to strengthen the joint.

Expect to spend about $550 on

materials for this bookcase if you

make it from walnut. Cherry or oak

would also be suitable but walnut

seems to be the right choice for this

project. You'll be using a little more

than a half sheet of 1/2" thick grade

A-2 walnut plywood for the shelves,

another half sheet of 1/4" thick grade

A-3 walnut plywood for the back and

about 50 board feet of walnut hard-

wood for the rest of the project. I rec-

ommend that you measure and mea-

sure again for all your cuts.

Frame and Panel Construction

The best place to start this project is

on the sides and the first step to any

frame and panel design is to glue up

the panels (pieces 5). Instead of glu-

ing up the six individual panels

(three for each side), I recommend

that you glue up just two longer pan-

els which can be cut to size, as shown

in Figure 1. This is standard proce-

dure among professionals and serves

to' create grain continuity on final

assembly. Saw and joint six pieces of

3/4" thick walnut 3

3

/4" wide and 40"

long. The six panels will actually be

45

' 3

h6"

Glue relief

15

7

h6"

1/4"

1/4"

Take your time when cutting mortises; the key to frame and panel construction is accurate joinery. If

you have a mortising attachment for your drill press, you should have little trouble. Another approach

is to make a template and use a plunge router and sharp mortising chisel.

cut to 13

1

/16" in length, so the 40"

length at this stage allows for kerfs

and uneven ends after gluing up.

Look for good color and grain match-

es, and once you're satisfied glue and

clamp your panels.

While your panels are drying you

can turn to the two frames, which

consist of 2 stiles and 4 rails each

(pieces 3 and 4). Cut all 12 pieces to

exact size as specified in the material

list on page 13 and lay the rails aside

for now. Carefully follow the mea-

surements in Figure 2 to layout the

mortise positions on the four stiles.

The tenons on the ends of the rails

will measure 1/4" T x 2" W X 11J4" L.

To cut the mortises in the stiles to

accept these tenons, I used a mortis-

ing attachment on my Delta drill

press and it worked very well. If you

don't have a mortising attachment,

you could also make a template and

use your plunge router or try a 1/4"

bit in a drill press (followed by a

sharp 1/4" mortising chisel). What-

ever technique you decide to use,

just be real sure that the eight mor-

tises are perfectly centered on the

edge of the four stiles and don't for-

get to allow an extra 1/16" in depth

for excess glue (See Figure 2).

Take your time on this step. Remem-

ber that cutting clean mortises

requires a lot of concentration and a

steady hand.

Now you're ready to cut the tenons

at the ends of the rails. I used a dado

blade on my tablesaw for these cuts,

relying on the miter fence and a com-

mon spacer jig for consistency.

Experiment with some 3/4" thick

The rail tenons will be 1/4" thick with a 1/4"

shoulder on the edges, requiring one dado blade

setting on the tablesaw. Practice with scrap to get

your setting right before cutting your material.

scrap wood until you can leave a 1/4"

thick tenon centered on the board.

Once the dado blade is set at the

right height, cut both faces of your

rails to form the tenon cheeks and

then flip them on edge to cut the

tenon shoulders, as shown in Figure

3. You'll want your tenons to fit snug-

ly into the mortises, so if you're new

at this be sure to carefully cut to size

in slight increments -you can't add

stock back once it's cut off. Dry fit

your two frames together now, check-

ing to make sure that all joints are

flush on the inner and outer faces.

You should also lay the two frames on

top of each other to make sure you

have a perfect match.

Once you're satisfied, chuck a 3/8"

TODAY'S WOODWORKER SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 1990

II

1/2" x 3/4"

Scrap

When routing the roundover on the inside of the

frames, use pieces of 1/2" wide scrap wood as a

stop to create an interesting corner look. Later,

this same technique is used on the door frames.

II

Panel raising bits should fit very tightly in the

collet of the router. Take off 3/16" from each side

with the first pass and then continue cutting on

the outside until your panel edge is 1/4" thick.

-

--

.... -1/4" dado

(1/ 4" deep)

--3/ 16"

I

3

1/4" inlo

lmorlises

t

Inside

L

/

Make the grooves for the panels with a 1/4" x 1/4"

slot cutting bit set at 3/16". Keep the router on

the inside of the side assemblies while cutting.

roundover bit in the router and use

spring clamps to position two pieces

of 1/211 thick x 3/4

11

wide scrap on

opposite stiles and rails to be used as

stops, as shown in Figure 4. Then

rout between them, bringing the pilot

on the bit right up to the spacer. The

object here is to leave about an inch of

r'l unrouted frame in each panel corner.

You're also establishing the outside

face of your side assemblies with

these cuts, so be sure to examine

your frames carefully and pick the

best looking stock to face out.

Routing The Panels

By now, your panels should be dry

and ready to cut to final size. Before

you start cutting, use a sharp cabinet

scraper to smooth both sides. Square

one panel edge on a jointer and rip

the other edge square, to a width of

10

11

116". Now cut three 13

1

M' long

panels out of each large panel.

I recommend using a heavy duty

router (3 h.p.) for the next step, since

you'll be taking off a lot of stock.

Chuck a sharp panel raising bit into

the router and make a single pass at a

depth of 3/16" all the way around

both faces of each panel. You're after

a final edge thickness of 1/4", which

is the size slot cutting bit you'll soon

be using on the frame. Increase the

depth by about 1/16

11

and continue

taking light cuts on the outside of

each panel until you have slightly less

than a 1/4" edge left, as shown in

Figure 5. Make sure your panel rais-

ing bit fits tightly in the collet of the

router. Without proper precautions,

large diameter bits can be dangerous.

Cut The Grooves For The Panels

Now you are ready to cut the grooves

in the stiles and rails. Remember that

panels are supposed to "float" in

frame and panel construction, so you

don't have to allow room for excess

glue. The panel will expand and con-

tract with the seasons however, so

when you test the fit, make sure

there's a little room for side to side

expansion. Before you disassemble

your frames, carefully number all

your joints so everything will go back

together nicely. Remember that the

top and bottom rails only need a

groove on the panel side.

Chuck a 1/4" x 1/4" slot cutting bit

into your router, set the depth at

3/16

11

and cut your slots from the

inside of the frame. To maintain the

integrity of the joinery, stop the

grooves 1/4" into each mortise, as

shown in Figure 6.

Assemble And Machine The Sides

Now that your stiles, rails and panels

are machined, you're ready to assem-

ble the sides. First do a dry assembly

of both sides, making sure the tenons

fit snugly into their mortises (with a

little room for glue) and the panels

float in the frame. A small plane and

some sandpaper will be handy at this

stage; you don't want to apply glue

until you're sure everything fits right.

When you're happy with the dry

assembly, take everything apart and

apply glue to the tenons. Do one side

at a time so the glue doesn't set up

early and, after 20 minutes of drying

time, go through both sides and light-

ly tap all the panels to make sure they

aren't getting glued in place by

squeeze-out. When the panels are

dry, rout a slight roundover on the

front edges of each front stile, stop-

ping 5/8" from the bottom so you'll

have a square corner for the base

assembly later (See Figure 7).

Before moving on to the shelf

dadoes, it's necessary to take a very

important sidestep. Both sides must

have 3/8

11

removed from their top on

the tablesaw. I didn't do this earlier

because I wanted to cut all my rails

and subsequent tenons with one saw

setup. Make these two cuts now on

the assembled sides.

Now set up your dado blade in the

table saw to make the 3/8" deep stop

dadoes that will hold the shelves. The

bottom three dadoes on each side

should stop 1" from the front and

should be 11/4" wide, centered on

each rail. (NOTE: Measure the thick-

ness of the plywood you'll be using

for the shelves before making these

dadoes. If it's slightly under 1/2",

then the dadoes should likewise be

slightly under 1

1

/4" wide.)

The top cut on each side is actually

a 111211 stopped rabbet, as shown in

Figure 8 . After cutting these rabbets,

use a saber saw to cut the notch at

the top front shown in Figure 8. The

tongue that is left will fit into a dado

that will be cut in the assembled top.

Finish up the two side assemblies by

routing a 1/2" deep x 1/4" wide rab-

bet on the inside back edges for the

1/411 plywood back (piece 2).

The Web Frame Shelves

Start on the shelves by cutting the

web sides, fronts and backs (pieces 7

and 8) to size and carefully assemble

the frames as shown in Figure 9.

Use two 3/8

11

x 11k" hardwood glue

dowels at each corner to strengthen

the joints. When you're done, you

should end up with four web frames

SEPTEMBER/OcrOBER 1990 TODAY'S WOODWORKER

5/8"

Once the glue dries on the assembled sides, rout

a slight roundover on the front edges of each

front stile, stopping 5/8" from the bottom so the

base assembly has a flat surface to attach to.

Top view

1_ 32

3

/4' -------..1

Even though the side dado stops 1" from the

front, the arc of the dado blade takes up another

11/4", thus the notch is cut back a full 21/4".

exactly 32

3

/4" long by 141/2" wide.

Now cut the four 1/2" plywood

shelves (pieces 1) to size and clamp

and glue them to your web frames.

To make the edge banding for the

front, slice 3/8" wide strips from 11J4"

thick stock (pieces 12) . Cut these

pieces to length and glue them to the

front edge of each shelf. When every-

thing is dry, trim any excess and

scrape off any glue. Cut the small

notch on the front ends of the

shelves, as shown in Figure 9. Once

the shelves fit into the sides, rout the

front of the edge banding for a fin-

ished look. I used a 3/16" beading bit

in my router to make the bead down

the center of each edge band and fol-

lowed with a 3/16" roundover bit on

the outside edges. If you prefer clean

square lines, just soften the top and

bottom edge of the banding with

sandpaper and leave it at that.

3/8" D x 1 1/4" W

Stop dadoes centered on __ --

1/2" D x 1/4"W

Rabbet for

back panel

The bottom three dadoes in the side pieces are simply centered on the rails, 3/8" deep by 11/4" wide.

Stop the dadoes 1" from the front. Make sure to measure the web frame shelf thickness before cutting

the dado. The top cut on each side is actually a 11f2" stopped rabbet. The final machining on the side

assemblies is to cut the small notch at the front corner, shown in step two at right.

Back edge

3/8" W x 1/4" D

stop dado

__ n-,- ro_nt_--:'-<1I f"j

3/16' x l ' slot

3/16" x 3/4" 161/2'

Front edge I.. 36

3

/8' --.. I

When attaching the solid wood top to its web frame, be sure to use elongated holes on the sides and

front to allow for expansion and contraction. Test fit the top on the dry-clamped sides and shelves

before cutting the stop dadoes on the underside of the web frame.

Assemble The Top

Like the shelves, the solid wood top is

supported by a web frame. Start by

gluing up the top (pieces 6), as you

did earlier with the side panels. When

it's dry, sand smooth and cut to fin-

ished size, 16

1

/2" wide by 36

3

/8" long.

Chuck a 3/4" Roman agee bit in the

router and rout the bottom of both

sides and the front, leaving the back

square. Add a light chamfer to the top

if you like. Now cut the top web frame

sides, back and front (pieces 9, 10

and 11) to the sizes shown in the

material list. As you can see in Figure

10, the web sides are square at one

end and mitered at 45 on the other

end. The front web piece is mitered at

both ends and the back is square.

Test the fit and then clamp and glue

this frame together. You're ready to

cut two stop dadoes now, but to make

sure they're positioned perfectly, I

recommend that you first dry clamp

the sides and shelves together to get

an accurate measurement. Once

you're sure of the placement, cut a

3/8" wide x 1/4" deep stop dado on

the bottom of each web side. Position

the dadoes 3/4" in from each side and

stop 1" from the front. The tongues

that you left on the top of each side

earlier will fit into these dadoes. Test

your fit and then rout a 1/2" radius

cove on the bottom edge of the front

and sides of this web frame, as shown

in Figure 1 O.

Take the assembled web frame and

drill three 3/16" diameter holes in the

back web piece. Then drill one long

slot at the center of each side piece

and three more long slots on the front

piece, as shown in Figure 10. All of

these holes and slots should be coun-

tersunk. Finish up by attaching the

web frame to the top, flush with the

SEPTEMBER/OcrOBER 1990 TODAY'S WOODWORKER

l1li

Front view

6

6

'iI3

r,

""

1

--'

3 CD

Since you're going to be mitering

these corners, cut your pieces 1/211

long and trim one unmitered end to

size on final fitting. To pick up the

molding style of the top, rout a 3/4

11

Roman agee on the top edge of the

front and side base pieces. Now miter

the front piece at both ends and the

sides at the front only. Cut the back

square with a 5/8

11

deep by 3/4

11

wide

notch at each end, as shown in Fig-

ure 12. Next cut the two dadoes

shown in Figure 12, one on the back

base piece and one on the front base

piece. These dadoes will accept the

cleats, (pieces 18) which are glued in

place with a 3

11

space left at each end.

The cleat and molding assemblies are

responsible for carrying most of the

weight of the unit, so be sure to get a

tight fit.

Once the dry assembly fits tightly, disassemble and glue and clamp the sides and shelves together.

The top assembly is attached with eight #10 by 13/4" wood screws.

back and centered from the sides

using #8 - 11/2

11

flathead screws. The

slotted holes will allow for expansion

and contraction of the top.

Assemble The Sides, Shelves and Top

By the time you finish this next step,

your bookcase will really start to take

shape. By now you've already done a

dry fit on your major pieces, so it's

time to glue and clamp the four

shelves to the sides and install the

top. I recommend that you use eight

#10 - 13/4

11

wood screws to attach the

top, four in front and four at the back,

as shown in Figure 11 above.

The Base Construction

Now comes probably the trickiest

sub-assembly of this bookcase. The

first step to assembling the base for

this bookshelf is to cut the front and

back spacer strips (pieces 13 and 14)

to size. Attach the rear spacer 3/4

11

in

from the back of the bottom web

frame, using glue and four #8 - 11/2'1

screws. Before gluing and screwing

your front spacer in position (flush

with the front of the stiles), rout a

1/ 411 radius down the length of the

top edge, as shown in Figure 12.

The next step is to machine the

base molding (pieces 15, 16 and 17).

Once the glue dries, screw the front

and back molding assemblies in

place, using four screws for each.

Glue the sides on now, using a web

clamp around the whole base and a

bar clamp across the rear. While the

glue is drying, cut the corner blocks

(pieces 19) to size and glue them into

the 3

11

space left in the dadoes at the

ends of the cleats, as shown in Figure

12. I recommend that you strengthen

this bracing with screws.

Finally, make the base shoe (pieces

20 and 21) by running a 1/211 radius

beading bit down the length of a wide

Bottom of shelf

Bottom of

web frame

Bottom of

side rail

3/4" W x 3/8" D

Dado

Base shoe front

Base sides

Corner block

The base is the trickiest sub-assembly on this bookcase. The key is to remember that the front and back molding pieces, along with their cleats, will carry

most of the unit's weight. As such, be sure that there's no play where the cleat fits into the dado on the two molding pieces. The side molding pieces are

simply glued into place at the end of the assembly. Corner braces are added to give the unit slightly more strength.

SEPTEMBER/ OCTOBER 1990 TODAY'S WOODWORKER

MATERIAL LIST

WALNUT PLYWOOD

Shelves & Top Spacer (4)

2 Back (1)

WALNUT HARDWOOD

3 Side Stiles (4)

4 Side Rails (8)

5 Panels (6) 3 per side

6 Top (3)

7 Shelf Webs: Side (8)

8 Shelf Webs: Front & Back (8)

9 Top Web: Sides (2)

10 Top Web: Back (1)

11 Top Web: Front (1)

12 Shelf Edgeband (4)

13 Front Base Spacer (1)

14 Back Base Spacer (1)

15 Base Front (1)

16 Base Sides (2)

17 Base Back (1)

Cut to final size at assembly stage.

TxWx L

1/2" x 14112" x 32

3

/4" (A-2)

1/4" X 32

7

/s" x 42112" (A-3)

3/4" x 2112" x 48"

3/4" x 2112" x 123/4"

3/4" x 3

3

/4" x 40"

3/4" x 5112" x 36

3

/8'

3/4" x 2" x 10112"

3/4" x 2" x 32

3

/4"

3/4" x 2112" x 15 7/8'

3/4" x 2112" x 30

1

/s"

3/4" x 2112" x 351/s"

11/4" x 3/8" x 32

5

/s" (edge slice)

3/4" x 2" x 32"

3/4" X 1

1

/2" x 32"

3/4" x 3" x 351/4"

3/4" x 3" x 16

3

M'

3/4" X 3

1

/8' x 33

5

/s"

TODAY'S WOODWORKER SEPTEMBER/OcrOBER 1990

TxWx L

18 Base Cleats (2) 3/4" x 2" x 27

5

/s"

19 Base Corner Blocks (4) 3/4" x 3" x 3"

20 Base Shoe Front (1) 3/4" x 3/4" x 36

13

/16"

21 Base Shoe Sides (2) 3/4" x 3/4" x 17"

22 Door Rails (6) 3/4" x 2" x 32"

23 Door Stiles (6) 3/4" x 2" x 13

7

/s"

24 Splines (12) 1/4" x 1/2" x 1

3

/4"

25 Slide Follower Strips (3) 3/4" x 3" x 31

3

/4"

26 Glue Dowels (32) 3/8" x 1

1

/2"

27 Quarter Round (6) 1/4" dia. x 48"

HARDWARE

28 #8 Screws (32) 1W'(Steel)

29 #10 Screws (8) 2" (Steel)

30 Flipper Door Slides (3 Sets) 14" (Steel)

31 Knobs (6) 1" diameter (Brass)

32 Glass (3) 3/16" x 10

1

/2" x 28

5

/s" (Tempered)

33 Wire Brads (42) 1 /2" (Steel)

34 #3 Screws (28) 1/2" (Brass)

II

Before you start machining your door frames, double check the size of your door openings to make sure

the material list measurements are still right on target. Use a slot cutting bit with the router table to

cut the grooves for the splines at the mitered corners of the door frames.

Machine the door frame exterior the same way

you did the side frames (see Figure 4). Then

disassembled and rout a 3/8" wide by 7/16" deep

rabbet on all inside edges to accept the glass.

Follower strip

When installing flipper door slides, the follower

strip is a key component, as it is the only link

between the doors and the slide mechanisms.

board and then ripping to final width.

Cut the base shoe pieces to length

and glue in place, using several

clamps for each piece.

Making The Doors

The doors have 2" wide frames that

are mitered at the corners with blind

splines. Before you start cutting the

door stiles and rails (pieces 22 and

23), go back and remeasure each

individual door opening to make sure

the material list dimensions are on

target. Now cut and miter the door

stiles and rails and use a 1/4" x 1/4"

slot cutter mounted in a router table

to cut the grooves for the splines. Set

your bit so it's 1/4" above the surface

of the table and start each groove at

the heel of each piece, stopping 1/2"

from the toe (See Figure 13). Now

cut your splines (pieces 24), shaping

one end to match the radius of the

groove.

Dry clamp the frames together with

a web clamp and use some scrap wood

and a 1/4" radius roundover bit to

create the same look as the side

frames. Mark all your joints, disassem-

ble and rout a 3/8" wide x 7/16" deep

rabbet on all inside edges of the rails

and stiles to hold the glass, as shown

in Figure 14. The final step on the

door assembly is to glue and clamp.

You're just about ready to install the

flipper door hardware, but first you

have to make the slide follower strips

(pieces 25) . Cut each of the three

pieces to size and then cut a 2" wide

by 1/4" deep dado 3" from each end,

as shown in Figure 15.

Unlike old fashioned double pin or weight

mechanisms, Accuride's flipper door slides

operate smoothly and effortlessly.

Hardware Installation

The key to installing flipper door

hardware is accurate slide placement.

Follow the manufacturer's instruction

sheet very closely and refer to "Hard-

ware Hints" on page 5 of this issue for

additional help. The photo above

shows the flipper door in action.

Once the slides are in and the

doors fit correctly, remove them and

install two brass knobs (pieces 31) on

each door. Now remove all of the

hardware and mount the glass in the

frames with mitered walnut quarter

round molding (pieces 27). Use 1/2"

wire brads (pieces 33), making sure

to pre-drill before nailing in place.

The last assembly step is to cut the

back (piece 2) to size and test the fit.

You'll install this piece with #3 - 1/2"

brass screws (four in each shelf web

and two between the shelves into the

rabbet on the sides), but hold off on

this step so you'll have easy access

for sanding and finishing.

When you're absolutely sure that

everything fits right, sand the entire

bookcase through 180 grit and finish

the piece with three coats of tung oil,

using 0000 steel wool between coats.

Reassemble your bookcase and load

it up with your favorite old books,

albums or art objects. One thing is

certain: you won't be able to overload

this sturdy piece of furniture!

T Martin Daughenbaugh is a wood-

worker from Minneapolis, Minnesota.

SEPTEMBER/ OCTOBER 1990 TODAY'S WOODWORKER

ClASSIC STRING TOP

( /Choose a soli d block of wood or laminate your own design. Either way,

thi s one day t urning project will yi eld a classic toy from days gone by.

By Craig Lossing

W

elcome

back to a

world classic.

In this article,

1'd like to rein trod uce

you to a toy that you

probably remember well

from the old days, the spin-

ning top. While they seem to be

a little out of favor in these mecha-

nized times, I can virtually guarantee

you that this is one gift the kids will

really love.

You can make these tops from solid

blocks of wood, but I thought we'd be

a little adventurous here and make a

multi-color laminated top out of

padauk and maple. Feel free to vary

the species, but to get a true spinner,

be sure to stay with woods of com-

mon densities.

Starting off, use 1/4", 1/2" and 3/4"

woods and laminate them into a 3" x

3" X 6" turning block. It's important

that the center of the block is solid,

and not a glue line, to eliminate the

chance of the lathe points splitting the

glue seam. I generally glue my blanks

with Titebond glue but turn to a two

part epoxy when using coco bolo or

other exotics.

Mount your top blank between cen-

ters on the lathe and turn it into a

cylinder about 21/i' in diameter. Leave

a space at each end, marking your top

3

1

/2" long. Using a parting tool, part to

1/2" diameter at each end. Now make

the 11/4" diameter notch with a small

gouge or scraper 3/8" from the top.

Round over the very top, work your

way down to the shoulder, and begin

rough shaping to the final size, as

shown above. At this point, don't go

beyond the string notch at the bottom.

Measure up 3/8" from the bottom

point and make another notch 1/2" in

diameter. Now finish tapering the

body, from the shoulder to the notch,

making sure you have a fluid curve.

Before moving on, sand the body

. "- ' (

down to 220 grit. The next step will

be a little tricky, so move with care.

Start to taper from the bottom notch

to the point. Turn to about 1/8" or

less. Cut the waste from the top and

sand it smooth. Remove the waste

from the bottom, making sure you

leave enough stock to make a fine

point. There may be some roughness

here, so shape the point by hand with

sandpaper or a knife.

Use your favorite finish to polish

your new top -I recommend a non-

toxic finishing oil. You now have a

beautiful top, but there's one last

step. You have to be able to tell some-

one how to make it spin!

A Quick Lesson In Spinning

It's really not that tough to learn

how to spin a top, the real key is in

how you wind your

string. The first thing

you're going to need

is s ome moderately

heavy cotton or nylon

string (about 1/16"

thick). Cut a piece

about fifty inches long.

Tie a knot at one end and a

loop to fit your middle finger

at the other end. Hold the top in

your left hand with the point facing

down. Press the knot of the string

under your thumb at the top of the

shoulder and wrap the string counter-

clockwise around the notch once and

over the knot, securing it in place

with your thumb again. Now, pull the

string down the body of the top to the

bottom notch and wrap it tightly in a

clockwise motion, in one layer, up the

body. Slide the middle finger of your

right hand through the loop, and hold

the toy with the point facing down.

To make the top spin, throw it

sidearm fashion toward the floor,

snapping your wrist back as it reach-

es the end of the string. If it didn't

spin the first time, try again!

Craig Lossing is a professional wood-

turner who teachs workshops regularly.

Headstock

~ - ' ' - - - ~ - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - ~ - ' - - - 1

Tailstock

Here's the layout for the paduk and maple top shown in the photo above. Don't feel constrained by the

traditional styling shown. Tops of any shape or form can be made to spin.

TO DAY'S WOODWORKER SEPTEMBER/ OCTOBER 1990

KID'S

STEP

STOOL

By Bill Johnson

W

hen you're making a step

stool for little ones, there

are three things to keep

in mind. First of all, the

stool will be carried around a lot,

mostly from the sink to the toilet, but

occassionally to other rooms in the

house. As a result, you must incorpo-

rate handles that are agreeable with

little children. With this design, teach

the kids to always pick their stool up

from the far side. That way, if they

stumble, the stool sits right down

without banging their knees.

Your stool should also be steady.

Really steady. One unfortunate fall

and you might be responsible for set-

ting potty training or hygiene back by

a month. Nobody wants that, and

that's why the sides are angled out.

And the final point is durability.

That's why I added screws and plugs

to the mortised joints. Anything

that's made for kids can use an extra

screw or two. Just ask any parent.

Getting Started

Before you start in on your template,

join the stock for all four pieces,

being sure to run a little large on the

sides and stretcher. While these

pieces are drying, start working on

the template.

Enlarge and transfer the drawings

of the sides and stretcher at right to a

1/ 4" hardboard template. (You won't

need one for the seat since it has no

curves.) When cutting the template

be sure to use the dotted red lines.

This extra 1/16" allows for the

router's template guide or bushing

when you make your actual cuts on

the oak. Spend enough time to get all

the curves on the templates just right

so you won't have so much sanding

on the final piece.

Clamp your template on one of the

sides and start by cutting the 3/8"

deep T-shaped mortise, using a 1/2"

straight bit with a 1/16" bushing in

the plunge router. Plan on making

two 3/16" passes. Now move onto the

handles, and cut all the way through,

taking several passes. Finish the

sides by routing the outside shape,

using the template as a guide.

Make the template for the stretcher,

following the red dotted line for the

curved bottom. Use the router to cut

the curved bottom and the table saw

for the other three sides. You can also

cut the seat out now, using the table

saw. Don't forget to cut the notches at

the ends of the seat and stretcher.

Before you start assembling,

there's a little more machining to

complete. Chuck a 1/4" roundover bit

in the router and roundover all non-

joining edges of the seat, stretcher

and sides, including the handles.

N ow cut a 3/8" deep by 3/4" wide

through dado down the center of the

seat bottom.

Do a dry assembly to check the fit

and while it's together drill three 3/8"

counterbored holes on each side, fol-

lowed by three 1/8" screw holes, in

the positions shown at right. Sand the

separate pieces through 180 grit and

glue, screw and clamp them together.

Once the glue dries, add your plugs,

resand the sides and finish with two

coats ofWatco Natural oil.

Bill Johnson is a professional woodwor/l-

er based in Minnetonlw, Minnesota.

SEPTEMBER/ OcrOBER 1990 TO DAY'S WOODWORKER

5" R.

::' ..

Each Square = 1"

I

3/8"

I

r

I

I

I

:,.;

1'>,'

<:

3/8"

p

33IB"

II

' I

I

I

. l

,

....." .. .. + I

' ....... _;.;.: ...... , __ :.r: ... ' ,

'" ......... :::;.. -1"

...... ""., "i""

MATERIAL LI ST

f . ,

,'; ,"

, ' .. :

.

TO DAY'S WOODWORKER SEPTEMBER/OcrOBER 1990

1 Sides (2)

2 Seat (1)

3 Stretcher (1)

4 Plugs (6)

5 Screws (6)

Tx Wx L

3/4" x 12" x 14" (Oak)

3/4" x 8114" x 12

3

/4"(Oak)

3/4" x 6114" x 123/4"(Oak)

3/8" x 3/16" (Face Grain)

#8 x 1114" Wood (Flat Head)

"IN -OUT" DESK TRAY

Stack these trays or use them individually - this versatile, decorative

design will organize your paperwork.

By David Ashe

I

f you're like most

folks, bills get thrown in a

drawer until it's time to pay

them. Out of sight, out of mind

doesn't always work however. Here's

an attractive solution that will orga-

nize those bills and keep them from

an early burial.

There's not much material in this

project. Basically you'll need 1/2" and

3/8" thick birch and a contrasting

veneer inlay strip. Begin by ripping

the 1/2" material 3

1

/2" wide. You want

two pieces at this point, each long

enough to make one whole side,

including waste. The inlay pieces will

be placed dead center along the

length of each board.

To set your router bit depth for the

inlay banding, here's a little trick.

Place two strips of inlay on a scrap

board about 3" apart. Set your router

down on the strips and adjust a

straight bit down until it just touches

the scrap, as shown in Figure 1. This

gives you the exact depth you need.

Now clamp your

wood down and cut

the inlay grooves on the 3

1

12" x 48"

boards. Depending on your inlay, you

may have to make more than one

pass to match the exact width of your

inlay strip.

Carefully clean out the groove with

a sharp chisel and apply glue along

the entire length. Starting at one end,

press the inlay strip into the groove

and wipe off any excess glue with a

damp cloth.

When all the strips are in place, set

the two inlaid faces together with

paper in between them(brown gro-

cery sacks work well), as shown in

Figure 2. The paper will blot any

excess moisture, and can be easily

sanded off later. Use some scrap to

protect the outside of the wood, and

clamp the whole sandwich until dry.

While the inlaid boards are drying,

rip 3/8" birch and edge glue to form

the two panels for the trays. (You may

want to glue up 1/2" material and sur-

face down to 3/8" when the glue is

dry. Cut the two trays 9

3

/4" wide and

then measure in 3/4" from each end

and make a mark. Continue to follow

the layout in Figure 3 to make the

trays. First use a belt sander to round

each corner and then cut the notches

on the long sides. When the trays are

machined, sand each surface to its

finished stage. Be very careful at the

To set the inlay groove depth, simply lay two inlay

strips on a board, straddle the router atop the

strips and lower the bit to just touch the board.

1990 TO DAY'S WOODWORKER

fI

Kraft paper

I

Clamp the inlaid boards together, face to face

with kraft paper in between, until the glue dries.

corners so you don't break off the

small tabs.

Miter The Sides

Now you can unclamp the 3

1

/2" strips

and sand off any leftover paper. What

you're going to do is make two pic-

ture frames from this strip, each of

which becomes one of the sides. Start

by marking the pieces so that one

edge is constant, assuring that the

inlay will match at the miters.

MATERIAL LIST

TxWx L

Now miter the four pieces for each

side, using the dimensions shown in

Figure 4. Do a test fit on each side,

and then join your miters with #20

plate joinery biscuits (if you or a

friend has a plate jointer) or chuck a

1/8" slot cutter in your router and

make a blind spline groove, as shown

in the exploded view at right. Glue

the spline or biscuits into place and

draw the four sided frames together.

Don't forget to wipe off excess glue

with a damp cloth as you go.

Sides (2) 1/2" x 31/2" x 48" (Birch)

frame side through the blade,

then flip the unit to cut the other

frame.

2 Trays (2) 1/2" X 9

3

/4" X 13" (Birch)

When the two frames are dry, rout

the 1/8" deep by 3/8" wide grooves

for the tray panels. Each frame

receives two grooves, positioned 2

3

/8"

in from the long edges. Dry fit the

3 Inlay Banding (3) 1/20" x 7/16;' x 36"

4 Brass Rods (4) 3/16" dia. x 2"

two trays into the dadoes in the frame

and if everything is fitting right, glue

and clamp the assembly.

When the glue dries, remove the

clamps and set the tablesaw fence to

cut the frame into two equal halves.

Make sure you're right in the middle,

because the trays work equally well

sitting next to each other. Pass one

- 3/8" W x 1/8" D

Dado

t

Form the trays by first rounding each corner, and then use a bandsaw to cut the long notches for fitting

the trays into the side frame dadoes.

TODAY'S WOODWORKER SEPTEMBER/ OCTOBER 1990

Use dowel centers to drill

matching 3/16" diameter holes at

each of the four joint locations to

accommodate the brass rods. Sand

the whole piece to 220 grit, then apply

two or three coats of oil. Finish up

this piece with a good quality paste

wax. These make a great gift for that

special executive friend or relative.

David Ashe is a woodworker based in

Des Moines, Iowa.

3

Sidepieces

1\ IS II, p, /I

Each side is cut from

a 4S" board.

Cut all the pieces for one frame out of the same

inlaid board to maintain color and grain continuity.

... ------ TODAY'S SHOP

Sharpening Basics, Part 2: (Honing)

By Roger W Cliffe

A well ground chisel or plane iron is

the important first step in developing

a truly sharp tool, which is where we

left off in our last installment on

sharpening cutting edges. Honing the

bevel is the next process. Usually you

want to hone the leading edge of the

beveled area to a pitch 5 to 10

greater than the bevel itself. For

example, if the cutting angle is 25,

then the honing angle would be 30

to 35. Most honing is done using a

honing stone and a lubricant. The

lubricant keeps the metal chips from

loading the fine cutting surface of the

stone and increases the smoothness

of the cutting edge.

The abrasives used for honing may

be natural or synthetic. The most

common natural stones are the

Arkansas stones. Synthetic stones

include diamond, aluminum oxide, sil-

icon carbide, and Japanese water

stones. Both natural and synthetic

stones will perform equally well.

The lubricants used with the stones

during the honing operation include

water and petroleum based oils. Gen-

erally, Arkansas, aluminum oxide, and

silicon carbide stones favor oil as a

lubricant. Diamond honing stones can

be used dry or with water. I prefer to

use water when honing any cutting

edge. It is less expensive and it leaves

less residue on your hands.

About the Stones

Begin honing the blade with a coarse

stone, which are available in silicon

carbide, aluminum oxide, 220 grit car-

bide water stone, and diamond.

These stones are coarse enough to

make quick work of grinding marks.

Once the coarse grinding marks

are removed, you can proceed to a

finer honing stone. Most fine honing

stones are easy to identify through

comparison with their coarser coun-

terpart. Many synthetic stones have a

coarse face and a fine face. A soft

Arkansas stone can be identified by

its mottled black and white appear-

ance.

Many woodworkers stop honing

after these two steps, and for general

woodworking this may be good

enough. Once the tool becomes dull,

it can be touched up with the fine

stone unless it has been nicked or

damaged.

Woodcarvers usually continue hon-

ing the cutting edge beyond the fine

stone level to improve the cutting in

softer woods, which tend to crush

rather than cut. There are hard

Arkansas stones which are either

pure white or pure black in color (the

black stone is finer than the white

and is not as common) and there are

also finer Japanese water stones in

the 1200 grit range . Any of these

stones can be used to continue the

honing process.

Some carvers will buff or strop the

cutting edge to make it even sharper.

This may be done with a buffing

wheel and jeweler's rouge or with a

leather strop similar to the one used

to sharpen a straight razor. The strop

may also be impregnated with an

abrasive such as jeweler's rouge. The

buffing or stropping makes carving

or cutting across the grain easier, but

this operation is not necessary for

general woodworking.

Getting the Edge

For best results, the stones should

remain stationary during honing.

Some woodworkers clamp the stone

in a vise; others make a wooden hold-

ing device for the stones. Once the

stone is positioned, the lubricant

should be poured onto the entire sur-

face of the stone. Position the tool on

the stone with the bevel laying flat,

then lift up on the tool about 5 to 10

so that only the front of the cutting

edge is on the stone. Exert some

downward pressure on the tool and

move it across the face of the stone

using a back and forth or figure eight

motion to spread the wear over the

entire face of the stone. This tech-

nique helps avoid forming a concave

surface.

Keeping the stone lubricated dur-

ing the honing process will make the

cutting edge smoother and keep the

stone from loading up with metal par-

ticles. The water or oil mixes with the

metal and stone particles, to speed up

the honing process. Continue work-

ing until the honed area is completely

smooth.

After each honing stage a thin piece

of metal remains attached to the cut-

ting tip called a wire edge. It rolls up

on the flat (opposite) face of the tool

and looks like a piece of wire. To

remove the wire edge, place the tool

flat on the stone with the cutting edge

SEPTEMBER/ OCTOBER 1990 TODAY'S WOODWORKER

up. Hone the flat surface of the stone

with a back and forth or figure eight

motion. You will see the wire edge

begin to break away from the cutting

edge after a few strokes on the stone.

It is important to remove the wire

edge after each grit level.

When you're learning to hone the

cutting edge on some very fine grit

stones you may want to use a honing

guide to avoid digging into the face of

the stone. These devices position the

cutting tool relative to the face of the

stone, assuring the correct angle.

Maintaining the Stones

Japanese water stones can be stored

in water when not in use. This will

keep them ready for sharpening at

any time. Keep the water clean,

changing it periodically so that it does

not become contaminated. If a

Japanese water stone becomes con-

cave or nicked, it can be restored with

220 grit silicon carbide wet-dry sand-

paper. Glue the sandpaper to a very

smooth surface such as a piece of

glass. The stone can then be worked

on the abrasive surface with water

until it is smooth. The abrasive will

wear out quickly, so you may need

two or three sheets.

Most other types of honing stones

are cleaned or wiped dry after use

and stored in a covered container.

The covered container prevents the

face of the stone from loading up with

fine sawdust. Working the face of the

stone with a wire brush may restore

it, but it is best to keep the stone cov-

ered. I have seen silicon carbide and

aluminum oxide stones trued up on

concrete, but this is slow -a perfect

punishment for the person who

allowed the stone to become concave

in the first place.

Dr. Roger Cliffe is the author of "Table

Saw Techniques" and "Radial Arm

Saw Techniques", published by Sterling

Publishing Co. of New YOI'll, New York

r WHAT'S I N STORE

The Veritas Stone Pond

By Hugh Foster

Before the Veritas Stone Pond

became available, I honed my tools

on oil stones, for almost everything

about using waterstones was kind of

a pain. Man-made waterstones must

be immersed in water for at least

five minutes before use, and they

should be stored wet so they are

ready for use at all times; natural

stones and those mounted on a

wood base are exceptions that func-