Professional Documents

Culture Documents

River Layout PDF

River Layout PDF

Uploaded by

hannavasinaCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

River Layout PDF

River Layout PDF

Uploaded by

hannavasinaCopyright:

Available Formats

A woman walks along the banks of the Yamuna near the Old Yamuna Bridge, a decaying, rusted heap

of iron in north New Delhi. The rivers inky, tortured water mixes with trash in pools along the side for a toxic-looking brew.

DELHIS FALLEN GODDESS

PHOTOS & STORY BY DAN HOLTMEYER

INDIAS FORSAKEN

RIVER

Dust floated in the ashen sky. The sun blasted down on New Delhi, Indias capital, like a furnace. May brought the end of the dry season a month of no rain and daily temperatures of 110 degrees Fahrenheit and up. Traffic honked and shouted its way, as it did every day, across the Old Iron Bridge. The Yamuna Rivers black, opaque water drifted under the bridge, smoothly reflecting the sky and speckled with inch-wide bubbles. Its smell, like rubber burning in a sewer, penetrated dust and traffic to reach nostrils two blocks away. Then something larger broke through the water: 24-year-old Chuman Miya surfaced for air, his face slick with the rivers oil his shoulders invisible just below the water. His hands appeared and sorted through a clump of sludge before tossing it away nothing this time. Miya glanced over at the dirt island surrounding a bridges pillar, which acted as the base camp for the dozen other boys and men who came each day to swim, boat and fish with magnets in search of a few dollars of coins and sellable scraps all day, every day. Their eyes are yellowed and their hands blackened by the river as if they dug up coal instead of metal.

The Yamuna swoops through northern India, linking Himalayan glaciers to the Ganges River one of the worlds largest rivers and as sacred to Hindus as Jerusalem is to Christians, Jews and Muslims. About onethird the way down, it crosses diagonally through New Delhi, a metropolis of more than 20 million people. Named after the sister of the god of death, the Yamuna River is revered as a goddess and prominent figure in ancient Hindu stories. Every few minutes, another pilgrim tosses in marigold garlands, god figures, family pictures, sequined cloth or rupee coins a Hindu

tradition to secure a blessing from Yamuna. Even Muslims toss in their own coins for luck. FALLEN GODDESS Today the sister of death is dying. Religious tokens arent the only human addition to Yamunas waters. According to the New Delhi government, one billion gallons of sewage are piped into the river daily, joining industrial wastewater, chemicals and heavy metals like lead and mercury. The toxic river stands as a monument to Indias meteoric population growth and development during the past several decades as it tries to exit the developing world. (Pollution) is all the river has after it enters the city, said Nitya Jacob, programme director for water at the Delhi-based Center for Science and Environment (CSE), which focuses on environmental research and related policy. Theres no fresh water, despite decades and billions of rupees in cleanup efforts only a cocktail of sewage and chemistry devoid of life remains, Jacob said. The river is dead, said Sunita Narain, CSEs director, in a 2007 interview with Fortune

A man sorts through bags and other trash on Yamunas banks, looking for coins or other sellable trinkets. Passersby on a nearby bridge throw money, religious images, coconuts and other offerings into the river, leaving the banks choked with trash.

The Yumana River

RIVER SOURCE: Yamunotri in the Himalayas; seat of the Goddess Yamuna LENGTH: 851 mi COVERAGE: Uttaranchal, Uttar Pradesh, Himachal Pradesh, Haryana, Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh, Delhi CITIES: Delhi, Agra, Allahabad Considered to be one of the most sacred rivers, along with the Ganges Goddess Yamuna is the daughter of Surya, the Sun God, and the sister of Yama, God of Death More directly connected to Lord Krishna, the most powerful incarnation of the god Vishnu, than the Ganges River

SOURCE

Two men scour the river from makeshift rafts, fishing for coins with magnets the size of hand weights. Many of the men are fathers and say they have no other way to make a living, at least for now. RIVER 5

INDIAS FORSAKEN

Banny harvests string beans on one of his fields, the Old Yamuna Bridge visible behind him.

Magazine. It just has not been officially cremated. Despite the dire diagnosis, residents of riverside neighborhoods, slums and farms continue to make their living from this dead river, and the city relies on it for much of its water supply. This dependence is one piece of Yamunas irony: Indians worship the river as a goddess for help but are steadily killing it. Many depend on it for their livelihoods and the Yamuna is hurting them back. RIVER TO PLATE Further down the east bank, several farmer families maintained pens of cattle and football field-sized plots of green beans, chilies and the knobby, bright green karela gourds. Birds chirped; traffic and

trains rumbled and honked. A creek of run-off water flowed from the farms to the Yamuna infused with dust, cow manure and pesticides.

The haggling increased in intensity; neither looked like backing down. Finally, Rani handed over one 500-rupee note, her lips clamped together.

the crux of the bridge and the bustling Swami Ganesh Datt Road. Bannys family sometimes used the rivers inky contents for their farm; neither Rani nor the family saw that as a problem. But they wouldnt touch the river themselves, and he admitted he couldnt grow watermelons here because of it. A recent two-year study from the Delhi-based Energy and Resources Institute found unsafe levels of lead, mercury, chromium and other heavy metals in the river, the soil nearby and the vegetables grown in it. UNICEF sponsored the study, which concluded in 2012. In some locations, mercury levels were 200 times safe limits, the study found. Such heavy metals are known to damage the development and function

A market for crops grown along the water convenes most evenings near the Old Yamuna Bridge in northern New Delhi. Virtually none of the buyers or sellers mind the use of Yamunas polluted water for food, though studies of that food have found mercury, lead and other toxic substances at levels far beyond any safe limit.

THE RIVER IS DEAD. IT JUST HAS NOT BEEN OFFICIALLY CREMATED.

In a farmers home with a thatched roof and tarp walls, a farmer and his customer were arguing. Raj Rani, a young woman in a turquoise and pink sari, wagged a finger at the leathery, deeply lined face and mournful-looking eyes of Banny Miya (no relation to Chuman), wielding one cucumber in her other hand. Several pounds of squash and karela were bundled on the dirt floor, their price still undecided. Banny and his family a wife, son and three daughters had grown and harvested the vegetables by hand on a farm theyd leased for a year for 12,000 rupees, or about $240. Its edge bumped against the Yamunas banks. The kids didnt go to school because the family couldnt afford it not that they wanted to anyway. Rani and one other customer sustained the Miya farming business, which in turn sustained her own she took the vegetables to sell at a market at

of almost every body system, particularly the nervous system and brain, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. One-fifth of the children near the river, researchers concluded, showed unsafe blood lead levels. Irrigating with Yamuna water was no concern for Rani and the other farmers, market vendors and shoppers. Everyone likes these vegetables, Rani said. Thats why Im here. Banny was about 60, he said, and while his permanent home was now 200 miles to the northeast in Uttar Pradesh, he was born nearby, across the river. Hed come back not out of religious devotion but to lease the land for the season.

Banny and his family were Muslim, but that didnt mean they didnt have a certain regard for Yamuna. Both religions have the same respect for the river, he said. They pray at the river and throw stuff in. We dont do it that way; we pray to it, but differently. Any farmer along the Yamuna respects the river because a crops fate rests in its annual temper. In June and July, air from the Indian

Everything around the old bridge will likely flood, recharging the fields with silt and nutrients, along with heavy metals and other contaminants. Babi Devi, a middle-aged woman whose farm near the bridge ran next to the candystriped Sai Baba Temple, lost her crop for the past three years to those floods. Hopefully not this year, she said as she shuffled down rows

trowel, her fingers stained red from the M&M-sized seeds. Move a foot forward, another pat. Her red bangles jingled with each tap, keeping a steady beat across the field. The beat paused now and then as Devi tucked her headscarf back into the front of her dress. While Banny irrigated from the Yamuna sparingly, Devi regularly pumped its water into shallow canals around her square plots. She recognized the stain of pollution but, like the others, was unconcerned by watering food with the caustic water. Even with that, our respect and sense of devotion is always the same, Devi said, Farmers gather regularly at the temple and offer fruits and other items, thrown into the water to please the river.

INDIANS WORSHIP THE RIVER AS A GODDESS FOR HELP BUT ARE STEADILY KILLING IT.

Ocean collides with warmer air trapped over India by the Himalayas, unleashing one of the worlds most powerful monsoons. of chili plants that looked like tiny trees in a miniature forest. Stooping, Devi patted bean seeds into the dirt with a

INDIAS FORSAKEN

RIVER

Saddams mother (bottom left) and his aunt, uncle and cousins scrub clothing together one May morning. Thanks to Indias location in the tropics, the temperature could surpass 90 degrees Fahrenheit before midmorning.

INDIAS FORSAKEN

RIVER

Saddam Khatom, 17, washes jeans and other clothes on a canal that juts from the Yamuna River, a sacred and exceptionally polluted river that cuts through the heart of New Delhi, Indias capital. His parents, aunts and uncles have washed clothes as a living for decades, but Saddam wants to go to school, become a civil engineer and do something famous, he said. Hajara Miya, Banny Miyas wife, talks with her mother one morning as the two harvest bitter gourds, or karela in Hindi. Hajaras three children also help out instead of going to school, which they say they cant afford and dont want.

It has nothing to do with its cleanliness, she said. Back at the Miya household, Hajara Miya, the mother, prepared dinner as the hazy sky darkened. She poked a dried plant stalk at the tiny earthen ovens crackling fire. A round silver pot held boiling potatoes above it. Her teenage daughter Shara squatted nearby, mixing flour and water in a wide, shallow bowl and squeezing the dough with her fingers. Shara glanced at her mother with a bashful smile every few minutes for pointers. Her younger sister hid in the back of the hut where painted flowers adorned the earthen portions of the walls. On the other side of a blue tarp wall from Hajara, her husband sat, saying little, smoking a ciga-

rette and watching the bridges always-noisy traffic go by. The Yamunas opaque surface, dark in the falling light, was just visible over the banks 50 yards behind him. Hajara had never seen the Yamuna clean, but her husband had. I could drink it right out of my hands, Banny said, cupping his hands together to demonstrate. Nowadays, all of the (sewage) drains are going to the river. Thats totally spoiling it. The water I used to drink I cant go near now, he said, shaking his head. Its painful. FAMILY BUSINESS About 10 miles downstream from the Old Iron Bridge,

17-year-old Saddam Khatom swung a sudsy pair of jeans against the inclined concrete bank of a Yamuna off-shoot canal. The staccato smacks rang out like gunshots. He stood ankle-deep in the gray water surrounded by ripples, which rocked a few scraps of trash and buoyant plants drifting by. Saddam paused between blows, kneading the cloth against the cement and squeezing out bleach and Fena-brand soap bubbles between his fingers. The caustic fluid trickled beneath him back to the river. He wore a dark orange plaid shirt and black slacks, some acne dotted his face, and his eyes were bright. Voices sounded from overhead. Saddam laughed softly, squinting up the bank in the morning glare at his aunt and his

mother, Momina, who worked a soup-like mixture of cloth, water and soap in a bucket. Her tongue poked out in concentration. The bunch often talks about other family members and plans for the future, they said, but at this moment teasing Saddam about getting a girlfriend soon was more fun. Several families of clothes-washers, dobiwallahs, were at work after hauling formless blobs of saris, bed sheets and other garments from their homes to the Yamuna for a thorough scrubbing. Washing machines are a lofty luxury. Kids joined their parents, aunts and uncles in the work, sometimes splashing each other or swinging jeans in faces. To get the most dust out, the dobiwallahs said, they smack the shirt or pair of jeans against

Saddam stands over his cousins bike, overloaded with clothing for washing, near the Yamuna canal. Escaping this living and becoming an engineer like Saddam wants remains a desperate challenge for many in his social position -- the vast majority of students in India dont make it to college, and Saddam admitted he didnt know for sure how he would pay for it. RIVER 11

10

INDIAS FORSAKEN

the concrete banks Saddam with more vigor than most of his neighbors a drumbeat that mixes with grunts of effort. Were content to work here, said Firoja Khatom, Saddams aunt, echoing most of the other parents. We cant make our living if we dont wash these clothes in the river. Kids sometimes jumped into the water, but most of the adults bathed at home, wary of skin sores and disease, Saddam said. Saddam shared their caution but not their contentedness. His father, Ishaq, had worked this job for 25 years; his mother, 16. Saddam wanted to be a civil engineer and do something famous. If I continue this job, Ill just be stuck like my parents, he

said in his familys two-room home. Outside the door was a dusty alley of Shaheen Bagh, a cluster of apartment buildings within walking distance of the canal. Its only enough for us to live, to fulfill our daily needs. So life is just going like this. I want something different. He spoke as he ironed clothes on a table in the main room where the family also slept stretching and folding with precise, quick movements. An old fan bolted to the ceiling squeaked a foot above his head. Most days are spent ironing. The TV set in the corner of two worn, pink walls displayed an episode of Man vs. Wild, the favorite show of Mohammed Saif, an 8-year-old neighbor who flitted in and out of the Khatom door like an adopted little brother.

Momina, Saddams mother, worked at another table outside against one of the walls, sometimes chatting and laughing with passing neighbors and the shopkeepers across the street. Bicycle vendors called out Pani! water in stretchedout syllables. Apartments reared over the maze of alleys, blocking out direct sunlight and housing shopkeepers, workers and some 50 other washer families. His 10th-class year over, Saddams summer holidays from school had begun. So he ironed. Less than one-fifth on Indias kids graduate high school, but to become a civil engineer Saddam would have to start by getting a diploma. Then hed have to go to college, something his family admittedly cannot afford. Saddam said hes counting on a network

of far-flung relatives to finance the loans. Well just try to support him, Momina said outside, as the coal rattled in her iron. A BETTER RIVER Momina had never seen a clean river, and Yamuna hadnt been drinkable in Saddams lifetime. Ishaq had seen it 25 years ago, however, after leaving a bakery business and taking up his fathers work. It was clean when I started, Ishaq said. Now, the government and other organizations figuratively skimmed the rivers surface once or twice a year. Nothing changes for long. Its very sad to see, Ishaq said. Its better to work

in clean water, but there is none. Indeed, the work of the government, dozens of NGOs and roughly 5 billion rupees ($100 million) has gone into Yamuna cleanup efforts over the past two decades, and the water is as resolutely black as ever. The government is now gearing up for the Yamuna Action Plan Phase 2, or YAP-II, after the lackluster results of YAP-I. The Indian government says the first phase had not focused enough on Delhis 10-mile stretch and on public awareness and mobilization. Nitya Jacob, the water program director at CSE, also pinned the blame to an overemphasis of building new sewage treatment plants instead of getting sewage to those plants.

Therefore, you have this huge volume of practically raw sewage, Jacob said. Then youre back to square one. All but one of 45 people living and earning along the river said it should be cleaned, though the divers and trash-pickers pointed out their dependence on the citys waste. We want a better life, said Gauri Singh, a fiery 25-year-old mother of two who sometimes collected trash near the Old Iron Bridge with her mother-inlaw. But who cares? Nothing changes. Nothing changes in our life. Still, Jacob saw some hope with YAP-II, which he said would focus more on sewer infrastructure to start diverting pollution at its source. He guessed significant progress would come in

the next one or two decades if YAP-II is implemented properly, including getting riverside industrial plants in on the game and exploring more ways to purify water. Its a question of pushing the government, the people, the media, he said. Theres no shortage of money. Its more a shortage of public awareness and government will. SADDAMS LOVE Another morning in late May, bright as always, Saddam Khatom scrubbed and swung clothes at the canal alone. His parents and younger sisters had gone out of the city for two weeks to visit relatives, leaving him and his older brother, who usually worked in a factory, to tackle the flow of laundry.

The temperature had edged into the upper 90s by 9 a.m. Sweat glistened on his lean frame. Still, he scrubbed. Saddam being able to pay for college, the water below him being clean both seem unlikely for now. Saddam, however, shared the hope invoked by Jacob. India is a very different country than others, but I love it, he said. You have to dream.

A man emerges from the Yamuna River after diving to the bottom in search of valuables. Men and boys along the river dive or throw in magnets from bridges and boats to find coins and other trinkets thrown in by passersby for a blessing from the Hindu goddess Yamuna.

12

INDIAS FORSAKEN

RIVER

13

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5819)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (845)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (348)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Sivananda Companion To YogaDocument192 pagesThe Sivananda Companion To YogaAndré Blas100% (13)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Surya Sahasranama StotramDocument15 pagesSurya Sahasranama StotramFoto KovilNo ratings yet

- Asia Conserved (For Web)Document450 pagesAsia Conserved (For Web)Sitta KongsasanaNo ratings yet

- What Is LoveDocument2 pagesWhat Is LovepkjoNo ratings yet

- ICAI Directory Final18-19Document204 pagesICAI Directory Final18-19Rajat NagpalNo ratings yet

- The Rama Story of Brij Narain Chakbast: Neil Krishan AggarwalDocument16 pagesThe Rama Story of Brij Narain Chakbast: Neil Krishan Aggarwaliona_hegdeNo ratings yet

- Mumtaz MahalDocument4 pagesMumtaz MahalDavid JasperNo ratings yet

- 4D/3N Bali Package Tour ADocument2 pages4D/3N Bali Package Tour Ad_shaputraNo ratings yet

- Naqshbandi Sufi Sheikh Lalaji Ra and Chachaji RaDocument15 pagesNaqshbandi Sufi Sheikh Lalaji Ra and Chachaji RaTaoshobuddhaNo ratings yet

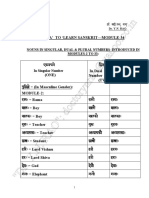

- Annexure 'A' To ' Learn Sanskrit Module 34' Round 8Document57 pagesAnnexure 'A' To ' Learn Sanskrit Module 34' Round 8Kushal RaoNo ratings yet

- 22 07 2017 Strem CSDocument19 pages22 07 2017 Strem CSMayankLovanshiNo ratings yet

- Bhakshana Samskaram: Constitution of IndiaDocument2 pagesBhakshana Samskaram: Constitution of IndiaAnonymous Hiv0oiGNo ratings yet

- The Indian Caste System Has Played A Significant Role in Shaping The Occupations and Roles As Well As Values of Indian SocietyDocument3 pagesThe Indian Caste System Has Played A Significant Role in Shaping The Occupations and Roles As Well As Values of Indian SocietyAnita RathoreNo ratings yet

- Clarifies On News Item (Company Update)Document1 pageClarifies On News Item (Company Update)Shyam SunderNo ratings yet

- The Eye of Horus (Udjat)Document2 pagesThe Eye of Horus (Udjat)Bea DaubnerNo ratings yet

- ArchivetempcompileDocument527 pagesArchivetempcompilepremNo ratings yet

- Is 1079 (2009) - Hot Rolled Carbon Steel Sheet and StripDocument13 pagesIs 1079 (2009) - Hot Rolled Carbon Steel Sheet and StripJeetu GosaiNo ratings yet

- List of Thermal Power Plants in India With Capacity PDFDocument6 pagesList of Thermal Power Plants in India With Capacity PDFPrashant PandeyNo ratings yet

- COMPANY PROFILE 2010@ Grasim IndustriesDocument20 pagesCOMPANY PROFILE 2010@ Grasim IndustriesAnkur DubeyNo ratings yet

- Vargottama RulesDocument2 pagesVargottama RulesGreh NakshtraNo ratings yet

- A Guide To Sanskrit Transliteration and PronunciationDocument4 pagesA Guide To Sanskrit Transliteration and PronunciationAdi W. BuwanaNo ratings yet

- A Critique of John WheelerDocument5 pagesA Critique of John WheelerSam Di CamilloNo ratings yet

- Acquiring Property in AstrologyDocument2 pagesAcquiring Property in Astrologyanu056No ratings yet

- Concise Tsok Offering Verse - DudjomDocument2 pagesConcise Tsok Offering Verse - DudjomEr Aim100% (2)

- PadmavatDocument11 pagesPadmavatkitty kujur100% (2)

- Delhi HC Puts Centre On Notice: HC Slams Unusual Haste' in Etala ProbeDocument12 pagesDelhi HC Puts Centre On Notice: HC Slams Unusual Haste' in Etala ProbeShah12No ratings yet

- Pankaj Srivastava (2) (1) - 1Document2 pagesPankaj Srivastava (2) (1) - 1ParasNo ratings yet

- Adi Sankara'sDocument31 pagesAdi Sankara'stummalapalli venkateswara rao100% (2)

- A.K. Ramanujan' S Is There An Indian WayDocument6 pagesA.K. Ramanujan' S Is There An Indian WayRatheesh Somanathan100% (2)

- Consolidated List of All UniversitiesDocument41 pagesConsolidated List of All Universitiessuraj kshirsagarNo ratings yet