Professional Documents

Culture Documents

瓦瓦V Flare

Uploaded by

Ajay SinghCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

瓦瓦V Flare

Uploaded by

Ajay SinghCopyright:

Available Formats

V Flare (P3GL2) was a Cypriot-registered bulk carrier that sank with the loss of 21 lives in the Cabot Strait

on January 16, 1998. Flare was en route from Rotterdam to Quebec when she broke in two during severe weather, approximately 20 nmi (37 km) west of Saint-Pierre-et-Miquelon on January 16, 1998. The stern section of the bulk carrier sank within 30 minutes while the bow remained afloat for days. 21 crew members perished, and four survived. The crew was able to send one truncated 20-second distress call that was received by the Canadian Coast Guard, who had to determine who and where the ship was within an area with a 40-mile (64 km) radius[1]. Some of Flare's crewmembers on the sinking stern section saw the bow of another ship appear to approach them, only to realize that it was the separated front half of their own vessel. The propeller on the stern section had still been turning, and had brought them back towards it. The survivors were rescued by a CH-113 Labrador helicopter from CFB Greenwood, Nova Scotia, belonging to 413 Search and Rescue Squadron of the Canadian Forces. The helicopter's crew consisted of aircraft commander Capt. C. Brown, co-pilot Capt. R. Gough, flight engineer/winch operator M.Cpl. R. Butler, and SAR Technicians Sgt. T. Isaacs and M.Cpl. P. Jackman. The lightly clothed survivors were taken to hospital in Saint-Pierre-et-Miquelon and treated for extreme hypothermia. The bodies that were recovered were collected by the French Navy, Canadian Coast Guard and Navy ships, and a Labrador helicopter from 103 Rescue Unit in Gander, NL. Flare's stern sank within minutes. The floating bow section drifted on the surface for several days, eventually sinking south of Cape Breton Island. Rogue waves seem to be clumped near a strong current such as the Gulf Stream off the North American east coast and the Agulhas Current off South Africa. The current, Lehner said, can act like a lens, focusing wave energy so that small waves combine into larger ones. But sometimes rogue waves appear out of the deep blue sea, in parts of the ocean without major currentsand scientists aren't quite sure why. The giant waves sometimes appear in areas of extended storms or converging weather fronts. Waves coming in from different systems could build up into big waves, Lehner said. Looking at more satellite data could help researchers learn even more about how and where the waves form.

The world's oceans claim on average one ship a week, often in mysterious circumstances. With little evidence to go on, investigators usually point at human error or poor maintenance but an alarming series of disappearances and near-sinkings, including world-class vessels with unblemished track records, has prompted the search for a more sinister cause and renewed belief in a maritime myth: the wall of water. Waves the height of an office block. Waves twice as large as any that ships are designed to ride over. These are not tsunamis or tidal waves, but huge breaking walls of water that come out of the blue. Suspicions these were fact not fiction were roused in 1978, by the cargo ship Mnchen. She was a state-of-the-art cargo ship. The December storms predicted when she set out to cross the Atlantic did not concern her German crew. The voyage was perfectly routine until at 3am on 12 December she sent out a garbled mayday message from the mid-Atlantic. Rescue attempts began immediately with over a hundred ships combing the ocean. "We hoped to find at least a life-raft with people. We never found a living soul" Captain Pieter de Nijs, Mnchen search co-ordinator The ship was never found. She went down with all 27 hands. An exhaustive search found just a few bits of wreckage, including an unlaunched lifeboat that bore a vital clue. It had been stowed 20m above the water line yet one of its attachment pins had twisted as though hit by an extreme force. The Maritime Court concluded that bad weather had caused an unusual event. Other seafarers could not help but consider the possibility of a mythical freak wave. Freak waves are the stuff of legend. They aren't just rare, according to traditional views of the sea, they shouldn't exist at all. Oceanographers and meteorologists have long used a mathematical system called the linear model to predict wave height. This assumes that waves vary in a regular way around the average (so-called 'significant') wave height. In a storm sea with a significant wave height of 12m, the model suggests there will hardly ever be a wave higher than 15m. One of 30m could indeed happen - but only once in ten thousand years. Except they do happen with startling frequency. Since 1990, 20 vessels have been struck by waves off the South African coast that defy the linear model's predictions. And on New Year's Day, 1985 a wave of 26m was measured hitting the Draupner oil rig in the North Sea off Norway. Concerned shipping operators wanted to know what was going on. The largest wave marine architects are required to accommodate in the design strength calculations is 15m from trough to

crest. If that assumption were to be proved false, the whole world shipping industry would face some very tough choices. What could cause such extreme waves? Curious about the spate of South African incidents, oceanographer Marten Grundlingh plotted the strikes on thermal sea surface maps. All the ships had been at the edge of the Agulhas Current, the meeting point of two opposing flows mixing warm Indian Ocean water with a colder Atlantic flow. Radar surveillance by satellite confirmed that wave height at the edge of this current could grow well beyond the linear model's predictions, especially if the wind direction opposed the current flow. Problem solved: the answer was just to avoid certain ocean currents in certain weather conditions. There was nothing freakish about large waves; the mariners' myth was an explicable phenomenon. To science, this was one that didn't get away. "Out of nowhere... a wave twice as high as average. The ship went down like freefall" Gran Persson, Caledonian Star First Officer Unfortunately, ocean currents could not explain two near disastrous wave strikes in March 2001. Once more two reputable ships, designed to cope with the very worst conditions any ocean could throw at them, were crippled to the point of sinking. The Bremen and Caledonian Star were carrying hundreds of tourists across the South Atlantic. At 5am on 2 March the Caledonian Star's First Officer saw a 30m wave bearing down on them. It smashed over the ship, flooding the bridge and destroying much of the navigation and communication equipment. The Caledonian Star limped back to port, her crew and passengers grateful that the engines had kept running, despite the onslaught. Just days earlier, the cruise liner Bremen had been less fortunate. 137 German tourists were aboard when she too faced an awesome wall of water in the South Atlantic. The impact knocked out all the instrumentation and all power, leaving them helpless in the tumultuous sea. Unable to maintain her course into the waves, there was a real risk the ship could go down and they knew none of the passengers would survive in lifeboats in such freezing conditions. With emergency power only, the crew battled to restart the engines. When they eventually succeeded, it opened the door to a very lucky escape. "We had said, 'This kind of thing can't happen; this kind of thing is too strange'"

You might also like

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- DrillingBasics English Version English NY 2008Document76 pagesDrillingBasics English Version English NY 2008Ajay SinghNo ratings yet

- RPT - DNV Recommended Practice (DNV-RP-C205) Environmental Conditions & LoadsDocument1 pageRPT - DNV Recommended Practice (DNV-RP-C205) Environmental Conditions & Loadsjdkelley0% (1)

- New DNV Recommended Practice DNV-RP-C205 On Environmental Conditions and Environmental LoadsDocument1 pageNew DNV Recommended Practice DNV-RP-C205 On Environmental Conditions and Environmental LoadsLiang SunNo ratings yet

- Technical Specification DP SystemDocument48 pagesTechnical Specification DP SystemAjay SinghNo ratings yet

- Extreme Ocean Waves 2nd Edition 2016 Edition 2015 PDFDocument242 pagesExtreme Ocean Waves 2nd Edition 2016 Edition 2015 PDFAngel JacomeNo ratings yet

- Design and Construction of Oil TankersDocument14 pagesDesign and Construction of Oil Tankersyw_oulala50% (2)

- B SC (Nautical)Document161 pagesB SC (Nautical)Ajay SinghNo ratings yet

- Emergency Towing Procedures Required For All ShipsDocument2 pagesEmergency Towing Procedures Required For All ShipsAjay Singh100% (1)

- Extreme Ocean Waves - 2nd Edition - 2016 Edition (2015) PDFDocument242 pagesExtreme Ocean Waves - 2nd Edition - 2016 Edition (2015) PDFEstebanAbokNo ratings yet

- Indian Holiday ResortsDocument4 pagesIndian Holiday ResortsAjay SinghNo ratings yet

- ASM June 2019 ISM ManualDocument10 pagesASM June 2019 ISM ManualAjay Singh100% (1)

- TidesDocument36 pagesTidesAjay SinghNo ratings yet

- Ship Waves in ChannelDocument25 pagesShip Waves in ChannelAjay SinghNo ratings yet

- Geology and OceanographyDocument1 pageGeology and OceanographyAjay Singh100% (1)

- MMD Ques - SSEMM - MP1Document9 pagesMMD Ques - SSEMM - MP1Ajay SinghNo ratings yet

- Fundamentals of Plate TectonicsDocument5 pagesFundamentals of Plate TectonicsAjay SinghNo ratings yet

- Fundamentals of Plate TectonicsDocument5 pagesFundamentals of Plate TectonicsAjay SinghNo ratings yet

- Fundamentals of Plate TectonicsDocument5 pagesFundamentals of Plate TectonicsAjay SinghNo ratings yet

- Anchoring and What Precautions To TakeDocument2 pagesAnchoring and What Precautions To Takevikrami100% (2)

- The Apparent Solar TimeDocument3 pagesThe Apparent Solar TimeAjay SinghNo ratings yet

- Procedure For Transmiting Designated VHF DSC Distress Alert From FurunoDocument1 pageProcedure For Transmiting Designated VHF DSC Distress Alert From FurunoAjay SinghNo ratings yet

- What Is Difference Between Maritime Survey N InspectionDocument1 pageWhat Is Difference Between Maritime Survey N InspectionAjay SinghNo ratings yet

- Ship TermsDocument30 pagesShip TermsAjay SinghNo ratings yet

- Phasei&II Syllabus 111010Document30 pagesPhasei&II Syllabus 111010He SheNo ratings yet

- Manual Resuscitator InstDocument7 pagesManual Resuscitator InstAjay SinghNo ratings yet

- ElQaher 2 Data CardDocument1 pageElQaher 2 Data CardAjay SinghNo ratings yet

- Equipment No 25 & 26Document2 pagesEquipment No 25 & 26Ajay SinghNo ratings yet

- First Aid KitDocument1 pageFirst Aid KitAjay SinghNo ratings yet

- Equipment No Na01 RadarDocument2 pagesEquipment No Na01 RadarAjay SinghNo ratings yet

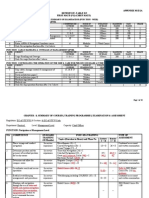

- Draught Survey BlankDocument3 pagesDraught Survey BlankThyago de LellysNo ratings yet

- Draught Survey BlankDocument3 pagesDraught Survey BlankThyago de LellysNo ratings yet

- Equipment No Na11 Speed LogDocument2 pagesEquipment No Na11 Speed LogAjay SinghNo ratings yet

- BL204 Radio SystemsDocument8 pagesBL204 Radio SystemsAjay SinghNo ratings yet

- Equipment No Sg01 Aldis LampDocument2 pagesEquipment No Sg01 Aldis LampAjay SinghNo ratings yet

- EQUIPMENT No NA12 Speed Log RepeaterDocument2 pagesEQUIPMENT No NA12 Speed Log RepeaterAjay SinghNo ratings yet

- Mode Locked Laser PDFDocument7 pagesMode Locked Laser PDFmenguemengueNo ratings yet

- Soal Try OutDocument6 pagesSoal Try OutIrawan WicaksanaNo ratings yet

- G I HS 9 - 1-2022 - Revision 41 For E12 Mock Test 21Document9 pagesG I HS 9 - 1-2022 - Revision 41 For E12 Mock Test 21suonghuynh682No ratings yet

- Walk On Haver PDFDocument8 pagesWalk On Haver PDFAlex RobertshawNo ratings yet

- Freak Waves South AfricaDocument4 pagesFreak Waves South AfricaflouzanNo ratings yet

- List of Rogue WavesDocument6 pagesList of Rogue WavesdescataNo ratings yet

- аð Ð - Ð Ð Ð - Раð аð Ð Ñ - 10 кð аñ Ñ - 2023-2024Document6 pagesаð Ð - Ð Ð Ð - Раð аð Ð Ñ - 10 кð аñ Ñ - 2023-2024nurkasym.nurilaNo ratings yet

- Rogue Waves: MARS 410 - Physical OceanographyDocument18 pagesRogue Waves: MARS 410 - Physical OceanographyReaz M.No ratings yet

- Abnormal WavesDocument23 pagesAbnormal WavesMalancha Bose MukherjeeNo ratings yet

- Extreme Ocean WavesDocument11 pagesExtreme Ocean WavesPatchole Alwan TiarasiNo ratings yet

- Extreme Waves and Ship DesignDocument8 pagesExtreme Waves and Ship DesignLyle Meyrick PillayNo ratings yet

- Draupner Wave: First Rogue Wave Captured on FilmDocument2 pagesDraupner Wave: First Rogue Wave Captured on Filmromulo100% (1)

- Exploring Rogue Waves From South Indian Ocean ObservationsDocument12 pagesExploring Rogue Waves From South Indian Ocean ObservationsVaisakh msNo ratings yet

- Rogue Wave - WikipediaDocument23 pagesRogue Wave - Wikipedia张杰No ratings yet

- Rogue Wave PDFDocument9 pagesRogue Wave PDFmenguemengueNo ratings yet