Professional Documents

Culture Documents

A Report On Sundarban Ecologi

A Report On Sundarban Ecologi

Uploaded by

JHmonirOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

A Report On Sundarban Ecologi

A Report On Sundarban Ecologi

Uploaded by

JHmonirCopyright:

Available Formats

1

Chapter 1 Introduction & Methodology

Objective of the Study The purpose of this study is to evaluate the ecological enemnonmene of Sundarban. The other purposes of the report are as follows: - To apply theoretical knowledge with practical situation. - To familiar with the history of Sundarban. - To gain some clear ideas about the animals and trees of Sundarban. - To know about the Climate condition & enemnonmene of seleceed anea. - To know the threat for ecology in Sundarban. Selecting Area The seleceed anea fon my neseanch ms Sundarban.

Map: Sundarban

Sources of Data This report was prepared mainly based on the secondary available data. Secondary data are those which have already been collected by someone else and which have already been passed through the statistical process. In this case one is not confronted with the problems that are usually associated with the collection of original data. Secondary data either be published data or unpublished data. The secondary data was collected from the relevant website.

Limitation of the Study - Lack of necessany mnfonmaemon. - Lmmmeed emme fname fon ehms seudy. - Thms seudy ms self fmnanced.

Chapter 2 Literature Review

The Sundarbans in Central Asia is a region covering some 10,000 sq. km of mangrove forest and water, of which some 40% is in India and the rest in Bangladesh. Part of the worlds largest delta, the area has been formed over centuries from sediments deposited by the Ganges, Brahmaputra and Meghna rivers, which converge on the Bengal Basin. The whole Sundarbans area is intersected by an intricate network of interconnecting waterways, of which the larger channels are often a mile or more in width. The unique hydrology of the Sundarbans, in addition to its great biodiversity, makes it an area of great importance to the millions of people who rely on the watershed daily for water, food and as a source of income. Despite a declaration by the Bangladeshi Governments Department of Environment in 1999 making the Sundarban an Ecologically Critical Area (ECA) under the Environment Conservation Act 1995, this sensitive area continues to suffer over-exploitation. Illegal urban development continues, including the use of bulldozers to extract sand at the confluence of Kalagachi and Chuna River at Burigoalini Range, within the Sundarban ECA. Mowdudur, together with a small committed team from the Centre for Coastal Environmental Conservation, has established a project which aims to raise public awareness of the ECA and its status as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. By putting forward ideas for sustainability in the Sundarban, and by raising awareness of the protection needs of its ecosystems and biodiversity among stakeholders and government agencies, Mowdudur is confident that people can be brought together to end the harmful activities which are threatening future livelihoods. Mowdudurs work focuses on increasing sustainability within an outstanding coastal area of the Sundarban and stemming the decrease seen in Olive Ridley Turtle populations. Working closely with local people and supported by a strong publicity campaign, the team is introducing Turtle Excluder Devices (TEDs) to fishermen and discouraging the use of basic drift nets in an effort to reduce the number of turtles killed unnecessarily through bycatch each year. An education programme targeting crab collectors has also been initiated to raise awareness of the negative impact egg collection is having on future populations of turtle. Beyond the fishermen, 1,500 members of the wider community of Dubla Rash Mela have also been made aware of the existence of the ECA and the harmful activities that are prohibited under the Bangladesh Wildlife Preservation Act.

Etymology The name Sundarban can be literally translated as "beautiful forest" in the Bengali language (Shundor, "beautiful" and bon, "forest"). The name may have been derived from the Sundari trees (the mangrove species Heritiera fomes) that are found in Sundarbans in large numbers. Alternatively, it has been proposed that the name is a corruption of Samudraban, Shomudrobn ("Sea Forest"), or Chandra-bandhe (name of a primitive tribe). However, the generally accepted view is the one associated with Sundari trees. Geography Brahmaputra and Meghna rivers across southern Bangladesh. The seasonally flooded Sunda The Sundarban forest lies in the vast delta on the Bay of Bengal formed by the super confluence of the Padmarbans freshwater swamp forests lie inland from the mangrove forests on the coastal fringe. The forest covers 10,000 km2. of which about 6,000 are in Bangladesh. It became inscribed as a UNESCO world heritage site in 1997. The Sundarbans is estimated to be about 4,110 km, of which about 1,700 km is occupied by waterbodies in the forms of river, canals and creeks of width varying from a few meters to several kilometres. The Sundarbans is intersected by a complex network of tidal waterways, mudflats and small islands of salt-tolerant mangrove forests. The interconnected network of waterways makes almost every corner of the forest accessible by boat. The area is known for the eponymous Royal Bengal Tiger (Panthera tigris tigris), as well as numerous fauna including species of birds, spotted deer, crocodiles and snakes. The fertile soils of the delta have been subject to intensive human use for centuries, and the ecoregion has been mostly converted to intensive agriculture, with few enclaves of forest remaining. The remaining forests, taken together with the Sundarbans mangroves, are important habitat for the endangered tiger. Additionally, the Sundarbans serves a crucial function as a protective barrier for the millions of inhabitants in and around Khulna and Mongla against the floods that result from the cyclones. The Sundarbans has also been enlisted among the finalists in the New7Wonders of Nature.

Chapter 3 Details about Sundarban

In the vast mangrove delta that stretches across eastern India and southern Bangladesh lies an anomaly. For it is here, in these tiger- and crocodile-infested swamps, that the goddess reigns. Yet, it is also here that women are nearly invisible.

The story of the Sundarbans is older than that of Bonobibi, the forest goddess who rules this land of mud and water. Yet, with this powerful goddess at the heart of the jungle, stories of human women are nearly non-existent.

Demographic accounts of women in the Sundarbans have them numbering about 932 for every 1,000 men. And, although they are central to their communities and families, they go nearly unperceived in both historical and present-day accounts. The women of the Sundarbans are nearly as enigmatic as the Sundarbans, itself.

What It Is The Sundarbans is a land of mystery. Cloaked in tangled mangrove roots and constant moisture, even the words meaning is uncertain. However, many speculate that it comes from the Bengali words "sundor," meaning "beautiful," and "bans," meaning "forests," as a reference to the local "sundari" or "sundri" tree, or from "samudraban," meaning "forests of ocean."

Covering 10,000 km2 of the southern Ganges River Delta, this marshy region stretches across both India and Bangladesh down to the Bay of Bengal. This is the world's largest mangrove forest. On the Indian side, alone, it equals sixty percent of the countrys total mangrove population.

The Sundarbans is best described as a combination of wetlands and jungle, including fifty-four islands characterized by their high salinity and changing forms. This area undergoes such intense, water-induced transformation that it needs to be re-mapped every three years.

Erosion is not a problem here although floods and cyclones are common. The tidal activity brings alluvial soils to build upon the already existing lands, and new islands are formed

frequently. Nevertheless, due to the salinity, instability of the islands, cyclones, and humaneating tigers, many consider this region uninhabitable.

Employment One of the characteristic statements used to describe the people of the Sundarban is that 85% of the people depend on agriculture. The proportion of the population without work in 1991 was 70% with only 3% in part-time or marginal employment and 27% in main employment categories. Of the main employment, only 10% are employed in agriculture as cultivators and another 10% as laborers. To obtain employment, local people migrate to access employment opportunities within the Sundarban or in Kolkata. Gender difference in workforce participation are high. Employment data indicates a structural under-employment issue. Given the existing structural nature of underemployment, this remains one of the critical developmental issues and a potential serious threat to future ecosystem integrity.

Sociological The Sundarbans, like a kaleidoscope, cannot be viewed using just one lens. Where stories are yielded, the Sundarbans becomes an anthropological and sociological dreamscape. Prior to the establishment of Sundarbans National Park in 1984, temporary fishing camps were established every season in order to ensure a fresh supply of fish to the Calcutta and other local markets. Although fishing once was not regarded as being as worthy an occupation as rice cultivation, it has always provided an important source of food in the Bengali diet. Fishing also has ensured the survival of those for whom it was the only possible livelihood. These temporary camps were set up on islands such as Indias Jambudwip, or Bulberry Island, bringing fishermen from villages as far away as Bangladesh.

These transient camps, which lasted about four months of every year, were inhabited almost strictly by men. Most either were unmarried or their wives and children were left at home.

10

Temporary fishing camps were favored over permanent settlements because the living conditions in the Sundarbans has discouraged many settlers. The regions demographics illustrate this, as hundreds of thousands of people have been killed by storms, eaten by tigers and crocodiles, or died of disease. Those who remain there work - with or without permits from the Forest Department - to collect honey, cut firewood, or fish. If killed within the bounds of the Sundarbans National Park, the families of the departed try to find and fetch the dead bodies to avoid trouble with the Forest Department staff. Often, these deaths go unreported for that very reason.

Biological From a biological perspective, the region is known for its great species diversity. Aside from the mangroves, which protect coastal areas from storms and provide important habitat and food source to the local marine life, about four hundred plant species populate this region. These plants dwell within each of the Sundarbans three ecosystems: the beach/sea face, the "formative" islands, and the swamp forests.

Many animal species reside within the Sundarbans as well. Creatures living here include chital deer, wild pigs, rhesus monkeys, olive ridley sea and other turtles, dolphins, 6 species of shark, king cobras, pythons, water monitors, enormous and rare estuarine crocodiles, and about four hundred species of fish. This area is home to many endangered species and has already seen the disappearance of the leopard, wild water buffalo, Javan rhinoceros, hog deer, and swamp deer.

The animal that has brought fame to the Sundarbans, however, is the Royal Bengal tiger. The recognition of its rapid demise in the late 1960s spurred a sudden interest in the protection of India's wildlife.

Illegal fishing boats often ply its thousands of channels to steal from the treasures embedded in this place. Hungry for money, pirates steal from the meagre holdings of those that live there or will kidnap and kill, ransom, or sell their newfound victims.

11

Fish, tiger, estuarine crocodile all play some role in the faraway world of markets and consumerism, a world disconnected from this place that abides by its own laws.

Hydrological The Sundarbans is a geomorphological and hydrological fascination. Few areas in the world undergo the transformation visited upon this place by the gods who are endemic to it. Water plays mud into different shapes, sculpting it into new islands and reforming the old. These drowned lands and everything that live in them have adjusted to tides that rise twice daily to a height of 6-9 feet.

Cyclone activity is more intense here than anywhere else in the world. Tidal waves 250-feet-high rise up the Bay of Bengal, funneling their way up the channels to disintegrate entire villages built on mud and made of mud - villages that are surrounded and protected from rising waters by mere 20-foot embankments. Both sides of the Sundarbans experience 4-8 cyclonic depressions every year.

Between 1960-1969, eleven major cyclones killed over 54,000 people in Bangladesh. Many of those were living in and around the Sundarbans. In November 1970, one cyclone, alone, accompanied by severe tides, killed 200,000 people. The cyclone of 1988 killed even more. And as the waters subsided, bodies could be found not only floating in the rivers but up high in trees. Somehow, though, the larger wildlife fares better. Few deer or tigers seem to be killed in these storms, but they sometimes are found, after the waters have subsided, clinging to the branches of the same trees. Terrestrial animals here have found ways to live in this water-bound place. Even pigs, monkeys, tigers, monitor lizards, and deer are swimmers in this saltwater environment.

Tiger The approximately 300 tigers that live here are part of the Sundarbans mystery, for it is here, in this thick mass of tree roots, writhing mud, and hungry water, that tigers stalk humans as prey.

The Sundarbans is famous for its tiger attacks and is one of the only areas in the world where "maneaters" are commonly found. Although the Indian government has estimated that only about

12

4% of the Sundarbans tigers are "maneaters," attacking locals entering the Reserve for honey, firewood, and other products, one maneater can kill dozens, if not hundreds, of people. The earliest attacks were recorded by a visitor to the Bangladesh Sundarbans in 1665.

Between 1948 and 1986, 814 people were killed by tigers in the Bangladesh Sundarbans. Between 1975 and 1981, an average of 45.5 people were killed each year in India's Sundarbans Tiger Reserve. The Indian government has undertaken steps to cut back on that number.

The reason for the tigers' killing of humans is unclear. One theory is that the salinity of the environment somehow gives the tigers the taste for human blood. Another is that the ingestion of so much salt damages a tigers liver and kidneys, making it irritable. More likely, the tiger has become accustomed to the taste of human flesh as a result of the cyclones and floods, which carry dead bodies down the water channels or strewn about to decompose.

Sundarbans tigers are like no other. They attack in the mornings and evenings between the hours when people enter and leave the forest. They swim, hunting in the water, hiding among mangrove roots as fishing boats pass until they spot an opportunity to approach from behind. Despite their size and weight, they stealthily sneak up on their victims from behind, typically grabbing them at the nape of the neck. When killing a deer, they embed their canines into four spaces in the vertebrae, a near lock-and-key fit. This method of killing is almost immediate.

Stories abound of Sundarbans tigers taking their prey with no trace. Men on small fishing boats hear a splash only to discover that one of their crew is missing. Perhaps they will see, as they frantically look overboard for their missing member, the wet tiger slinking up the mud bank of the shore dragging its meal by the neck.

Tigers have been known to swim out to larger boats and leap aboard. Those on board may begin to call out, "Ma," or mother, a word meant to hail the goddess Bonobibi.

Legend has it that the echoes of someones screams at facing a tiger are eaten by the tiger. No one hears the scream as the tiger takes its prey.

13

Altered Landscape How does one understand the true essence of the Sundarbans? The Sundarbans region has long been one of India's last frontiers, an uninhabitable thicket of mangrove swampland separating the expanding Indian population from the Bay of Bengal. India's ruling powers viewed this area as wasteland, and a great deal of hard labor was spent in making use of the land. The resulting conversion of the mangrove swamps and northern forests into paddy land for wet rice cultivation, the use of the area's natural resources, hunting, and poaching have all contributed to the degradation of this region.

The conversion of forested land into rice paddies began long before the Muslim Indo-Turkish sultans ruled Bengal from 1204 until 1575. History carries their stories, as real as the mud. The reverence of forest-clearers continued into the Mughal period, which lasted from 1575-1765, until the British came to power. The locals continued converting the Sundarbans jungles to wet rice fields and were heavily influenced by their colonizers.

As a result, the Sundarbans storms have become more frequent. From 1891-1960, there were 16 severe tropical storms that pounded Bangladesh; between 1961-1977, there were 19. Deforestation of the mangroves that once helped to protect that coast from high winds and waves is thought to be part of the reason. In 1900, 40% of India was covered with jungle. Today, about one-third of those trees remain. Similarly, the Sundarbans is losing its trees, particularly in the land-girded north, as attempts at industry, tourism, and land reclamation are made.

Within the past three hundred years, the two horned rhinoceros, the Indian cheetah, the golden eagle, and the pink headed duck, all species indigenous to the Sundarbans, have disappeared. Cyclones are more frequent and powerful. And it is believed that the conversion of the natural forest to agriculture means that people are abandoning their gods.

British reports referred to the Sundarbans as "a sort of drowned land, covered with jungle, smitten by malaria, and infested by wild beasts." What made it uninhabitable wasteland was the "gross fertility of the vegetation." The administrations sentiment was that the Sundarbans was "a

14

land covered over with impenetrable forests, the hideous den of all descriptions of beasts and reptiles, ...only...to be improved by deforestation."

From the very beginning of British administration in Bengal, the area was thought more of a nuisance than an advantage, to be drained, embanked, and reclaimed for cultivation. However, cultivators were not the only ones trying, largely unsuccessfully, to clear the forest. Woodcutters also faced a challenge in cutting down trees that were enmeshed with one another in such a way that they could only be removed one piece at a time.

Bonobibi To the people who live there, the Sundarbans is an area to be both feared and revered. While it is true that the tiger resides there, the tiger goddess lives there, as well, and offers her protection to those who enter the forest with care and respect. Those who earn their living by collecting honey, fishing, or cutting firewood take precautions before undertaking their duties.

The goddess Bonobibi was born of Gulalbibi, whose husband Ibrahim had been forced to abandon her, pregnant, in the forest. Because his first wife had been unable to bear him a child, she had allowed him to take a second wife. However, jealous of Gulalbibis conception, Ibrahims first wife had demanded that he abandon the pregnant woman as she slept. When she awakened, Gulalbibi realized that she had been left and called out to Allah to sav e her. He sent fairies to help her give birth to her twin children Bonobibi and her brother Sha Jungli. Beneath the weight of single motherhood and twins, Gulalbibi left the forest, and her daughter, behind.

The forests small spotted chital deer found the baby and nursed her. Allah protected her and, filled with magic, Bonobibi became a goddess. One day, her brother came to find her. Both Bonobibi and Sha Jungli knew that they could not go live with their parents. Instead, they chose to go to the Sundarbans and help to alleviate the suffering of the people there.

Manasa A four-armed goddess of snakes also inhabits the Sundarbans. She name is Manasa, and she represents the serpent, which is the symbol of water, something vitally important to this area

15

impacted so strongly by the monsoons. Although thousands are killed each year by snakes in India, people continue to honor snakes, which are believed to bring the monsoon. Manasa is a protector of snakes and of people from their deadly poison.

Prayers Clearly, the harsh realities of this region have been incorporated into the cultures of the local human inhabitants. The many rituals and taboos that have been created are good indications of the insecure lives that these people lead. In addition to offering the comfort of protection, it weaves the sacred to their everyday tasks.

The Forest Department requires all wood-cutting parties to be accompanied by a shaman whenever they enter the forest. Some faqirs, or shamans, are so powerful that they are thought to drive away crocodiles, tigers, and snakes and keep the people with them safe. Sometimes, this protection can last for months after a shaman has offered his prayers.

The men who work in the forest, who live in the Sundarbans, sometimes dream of encounters the goddess Bonobibi. They call on her as their mother, or Ma, and ask for protection as they make their ways through the forest. Here is another shamans prayer:

O Mother Thou who lives in the forest, Thou, the very incarnation of the forest, I am the meanest son of yours. I am totally ignorant. Mother, do not leave. Mother, you kept me safe inside your womb For ten months and ten days. Mother, replace me there again, O Mother, pay heed to my words. (Sy Montgomery, Spell of the Tiger, p. 187)

16

Although these prayers are thought to bring protection to those in the forest, some of the shamans in the Sundarbans agree that miracles, such as goddess visitations, do not happen as frequently as they used to. Now, people are impure, and goodness is leaving the world.

Women The Sundarbans is a demanding home to those who live there. It requires much of those who live there in order to survive, regardless of their gender. It requires prayers to Bonobibi, humility and gratitude, ingenuity, and tolerance.

Living and working in the Sundarbans is dangerous. And just as the men do it, so do the women. It requires both men and women to work hard and face many of the same dangers. Yet, although the mens lives have been documented by anthropologists, the story of the Sundarbans women remains nearly untold. Instead, like Bonobibi, their lives, like their stories, are shrouded, not quite palpable. Yet, they do not have the power of the goddess.

The women of the Sundarbans are practically unknown outside their direct social relationships. It has been the exploits of men, the colonization by men, and the work of men that has captured the interest of historians. In reviewing past and current accounts, the male woodcutters, fishermen, and honey collectors are those that are discussed, regardless of the fact that the women contribute not only to domestic chores but their families incomes.

Women of the Sundarbans work not only taking care of household duties but often to help the family survive financially. Some of them cultivate on family plots while others fish. Fishing for prawn is a particularly dangerous job and one taken on by women and their children who may move through the waters, waist or neck deep, dragging nets behind them to catch their prey. Each year, women and girls are lost to crocodiles and tigers in this way.

Sundarbans women are translucent like the watery place, itself. Scarcely has there been attention when tigers and crocodiles maim or kill women, and these attacks often remain unheard by those outside the local community.

17

Sundarbans women tend to marry early, becoming a bride sometimes by the age of 12. When women lose their husbands from tiger attacks, particularly if their husbands were not permitted to enter the forest to take fish, honey, or wood, they often are forced out of their homes with their children and made to live in widow villages. Here, they must be the sole providers for their families and take on the roles traditionally taken by the men wood cutting, honey collecting, and fishing.

One anthropologist studying shamanism in three Sundarbans villages found that women were usually the ones treated for spirit possession were women. It was assumed by several local holy men that the reason for this was simple women are weaker than men, and because menstruation makes them ritually impure for several days each month, they are open and vulnerable to spirit possession. According to the study, the women who were treated for possession generally were in lonely or abusive marriages. In some cases, their husbands were away for extended periods of time; in others, their husbands or mother-in-laws mistreated them.

Perhaps, in an area inhabited by those things that cannot be seen by tigers that creep up from behind, by pythons wrapped in trees, by crocodiles and microbes that inhabit the waters this form of expression is appropriate. How else could a disempowered woman express her power appropriately? For, in a culture that defines a womans power as being limited to certain things, she cannot boldly move and speak in any way she wishes she must do so through a set of culturally constructed means. I dont mean to imply that spirit possession is impossible I only mean to state that possession may be one way to power.

Little is known of the personal stories and collective experiences of the Sundarbans women. Here, men are opaque and visible in their relationship with the place. The men have been known as the architects of this lands development and the conservers of its natural heritage. It is their stories that are shared, common in the history of a patriarchy.

However, immersed in water or hidden like the mist of a goddess that sometimes emerges in the dreams of men, the womens stories lie dormant to those outside their own worlds.

18

Chapter 4 Threat to ecology of Sundarbans

19

THE World Heritage Convention has the responsibility of protecting outstanding natural and cultural areas that form a part of the heritage of all mankind. Bangladesh became a party to the Convention in 1983. The Convention ruled favorably on the nomination of a part of the Sundarbans as a World Heritage Site.

Environmentalists and nature lovers felt deeply disturbed when they learnt about setting up of a 1,320 MW coal fired power plant at Rampal just 14 km away from the Sundarbans. Coal-based power plants create serious environmental pollution. No country would allow them to be set up even within 20 to 25 km distance from either forest or agricultural or residential area. How could the Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) group approve it even after acknowledging the dangers it held? The area is linked with the Sundarbans by a network of rivers and canals and environmental degradation of this area caused by the power plant will definitely spread to the Sundarbans region.

The Sundarbans region is an ecologically critical area. EIA, in its impact assessment report, admits that the 142 tons of sulphur dioxide and 85 tons of nitrogen dioxide that will be emitted daily from the plant will increase the concentration of Sulphur Dioxide (SO2) and Nitrogen Dioxide (NO2) in the air near the Sundarbans. Even after admitting that so much emission will be destructive for the whole environment of the Sundabans region, they take the defence that on a 24 hour basis 53.4 microgram of SO2 per cubic metre does not exceed the 80 microgram per cubic metre, which is an allowable limit set by the MoEF for residential and rural areas. The argument is confusing because the mangrove forest is not a residential area by any reasoning, criteria and consideration. In the same vein, it claims that although the concentration of nitrogen dioxide would increase three-fold from 16 microgram per cubic meter to 51 microgram per cubic metre, it is still safer and much below the Environmental Conservation Rule 1997 (ECR). Actually, the emission standards set for ecologically sensitive area is 30 microgram per cubic metre both for SO2 and NO2, which is much below the resultant concentrations that are likely to be released from the plant. It defies logic to treat the Sundarbans, the largest mangrove forest, a Ramsar site and Unesco World Heritage Site, as a residential area instead of an ecologically critical and sensitive area.

20

Chapter 5 Findings

21

The Sundarbans in Central Asia is a region covering some 10,000 sq. km of mangrove forest and water, of which some 40% is in India and the rest in Bangladesh.

Declaration by the Bangladeshi Governments Department of Environment in 1999 making the Sundarban an Ecologically Critical Area (ECA) under the Environment Conservation Act 1995.

85% of the people depend on agriculture.

The name Sundarban can be literally translated as "beautiful forest" in the Bengali language (Shundor, "beautiful" and bon, "forest").

Between1960-1969, eleven major cyclones killed over 54,000 people in Bangladesh. Many of those were living in and around the Sundarbans.

Between 1948 and 1986, 814 people were killed by tigers in the Bangladesh Sundarbans.

Between 1975 and 1981, an average of 45.5 people were killed each year in India's Sundarbans

The peoples of Sundaeban believe on Bonobibi and Manasa.

The women of the Sundarbans are practically unknown outside their direct social relationships

22

Chapter 6 Recommendation

23

Located in the Southern extremity of the Ganges River Delta, Sundarban with an area around half a million hectares is the world's largest mangrove forests with a rich aquatic and terrestrial biodiversity. It plays a significant role not only in the local livelihoods of South-Western region but also in the national economy of Bangladesh. About a dozen of donor-funded projects have been implemented since 1960s in and around Sundarban in natural resources sectors including forestry, water, agriculture, fishery, oil and gas. Out of them, Costal Embankment Project (196067), Khulna Jessore Drainage Rehabilitation Project (1995-2002), Gorai River Restoration Project (1995-2002) and Sundarban Biodiversity Conservation Project (SBCP) (2002-06) are the major projects operated in Sundarban area. The article argues that the overall impacts of the former three projects on environment, local employment and agricultural productivity were found rather negative. Therefore, a local alliance has been made among NGOs, CBOs, civil societies, journalists and local people to save Sundarban from negative project impacts and enhance sustainable environmental, social and economic benefits. The alliance also works as a 'watch group' of SBCP. The article criticizes the strategies and practices of SBCP and recommends to recognize the rights of the local people on common natural resources for sustainable management of Sundarban.

24

Chapter 7 Conclusion

25

Trees are the most essential bounties in nature contributing to the sustenance of life on earth. The largest mangrove forest Sundarbans is therefore contributing to the sustenance as well as safety of living beings in major part of Bangladesh. Unscrupulous human interventions are the major threat to nature. Similarly climate change: the fallout of exaggerated interventions in the name of development is horrifying the nature, including the Sundarbans. Flowing water in the rivers, canals etc through and around the Sundarbans flush out saline water intrusion from the sea. Increase in salinity intrusion due to anticipated sea level rise is one of the major threats to the Sundari trees, which are already under threat due to increased salinity levels. Majority of the negative impacts in the Sundarbans aggravate during dry periods when the flow of the Gorai River, the main feeder of thee water bodies of the Sundarbans, falls drastically. The flow characteristics of the Gorai River depend on the Ganges River from which it is originated. However, the environmental flow of the Ganges River in the Bangladesh part has shrunk to a great extent due to construction of the Farakka Barrage on the river by India. So it has become almost inevitable to construct a barrage across the Ganges River in the Bangladesh part at downstream of Ganges-Gorai junction to store water for feeding into the Gorai River. This will increase the environmental flow of the Gorai River, particularly during dry periods and minimize the anticipated negative impacts of climate change. It cannot be ignored that the proposed barrage will pose some negative impacts, which shall have to be well addressed; alternative mitigating measures are to be taken into active considerations.

26

Reference

http://www.nepjol.info/index.php/NJF/article/view/973 www.ulab.edu.bd/books/Social-Water-Managment/ www.agdevjournal.com/ http://www.sadepartmentwb.org/Socio_Econimic.htm onsearchoflight.blogspot.com/

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5814)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1092)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (845)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (348)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Under The Mountain, Maurice Gee 9780143305019Document8 pagesUnder The Mountain, Maurice Gee 9780143305019Cristina EstradesNo ratings yet

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Lesson Plan in General Physics 2Document5 pagesLesson Plan in General Physics 2Mafeth JingcoNo ratings yet

- BedZED Housing, Sutton, London BILL DUNSTER ARCHITECTS PDFDocument3 pagesBedZED Housing, Sutton, London BILL DUNSTER ARCHITECTS PDFflavius00No ratings yet

- Grecia AnticaDocument100 pagesGrecia AnticaIoanaCeornodoleaNo ratings yet

- 14-Nm Finfet Technology For Analog and RF ApplicationsDocument7 pages14-Nm Finfet Technology For Analog and RF ApplicationsTwinkle BhardwajNo ratings yet

- PG 511 B 1 B 1: Ordering Code Series PGP/PGM511Document7 pagesPG 511 B 1 B 1: Ordering Code Series PGP/PGM511Zoran JankovNo ratings yet

- Pierre Pontarotti Eds. Evolutionary Biology Genome Evolution, Speciation, Coevolution and Origin of LifeDocument393 pagesPierre Pontarotti Eds. Evolutionary Biology Genome Evolution, Speciation, Coevolution and Origin of LifeJesusNo ratings yet

- Cause & Effect WorksheetDocument2 pagesCause & Effect WorksheetAh Gone67% (3)

- NCM 210 RLE - 10 Herbal Plants Approved by DOHDocument6 pagesNCM 210 RLE - 10 Herbal Plants Approved by DOHLYRIZZA LEA BHEA DESIATANo ratings yet

- Verification and Validation in CFD and Heat Transfer: ANSYS Practice and The New ASME StandardDocument22 pagesVerification and Validation in CFD and Heat Transfer: ANSYS Practice and The New ASME StandardMaxim100% (1)

- Katalog SPRigWP JALANDocument1 pageKatalog SPRigWP JALANemroesmanNo ratings yet

- MOS Structure Lifting PlanDocument15 pagesMOS Structure Lifting Planmuiqbal.workNo ratings yet

- Final DWG With PicsDocument1 pageFinal DWG With PicsMuhammad AfrasiyabNo ratings yet

- PR1 DecenillaJDocument24 pagesPR1 DecenillaJjerichodecenilla98No ratings yet

- Caterpillar C7 & Gep 6.5L (T) Fuel System Durability Using 25% Atj Fuel BlendDocument92 pagesCaterpillar C7 & Gep 6.5L (T) Fuel System Durability Using 25% Atj Fuel BlendAdhem El SayedNo ratings yet

- Washing Machine: Service ManualDocument51 pagesWashing Machine: Service ManualMihai LunguNo ratings yet

- Universal Preschool Is No Golden Ticket: Why Government Should Not Enter The Preschool Business, Cato Policy Analysis No. 333Document31 pagesUniversal Preschool Is No Golden Ticket: Why Government Should Not Enter The Preschool Business, Cato Policy Analysis No. 333Cato InstituteNo ratings yet

- Informational Content of Trading Volume and Open InterestDocument7 pagesInformational Content of Trading Volume and Open InterestadoniscalNo ratings yet

- Module 2 Trends NetworkDocument11 pagesModule 2 Trends NetworkBianca TaganileNo ratings yet

- UCS-X - Includes - FullParticipationGuide - Addendum 1 - 05.16.22Document307 pagesUCS-X - Includes - FullParticipationGuide - Addendum 1 - 05.16.22Ali Khaled AhmedNo ratings yet

- (Bohdan Dziemidok, Peter McCormick (Eds.) ) On TheDocument310 pages(Bohdan Dziemidok, Peter McCormick (Eds.) ) On TheMarina LilásNo ratings yet

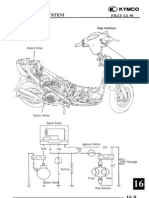

- F50LX Cap 16 (Imp Avviamento)Document6 pagesF50LX Cap 16 (Imp Avviamento)pivarszkinorbertNo ratings yet

- Annual Budget CY 2023Document180 pagesAnnual Budget CY 2023robertson builderNo ratings yet

- The World of Psychology Seventh Canadian Edition Full ChapterDocument41 pagesThe World of Psychology Seventh Canadian Edition Full Chapterwendy.schmidt892100% (27)

- Attachemnt A - Body and Wheelchair MeasurementDocument2 pagesAttachemnt A - Body and Wheelchair MeasurementNur Adila MokhtarNo ratings yet

- Pemberian Obat Dengan Kewaspadaan Tinggi Pada Pasien ICUDocument38 pagesPemberian Obat Dengan Kewaspadaan Tinggi Pada Pasien ICUIndriWatiNo ratings yet

- Tutorial Details Program: Coreldraw 11 - X5 Difficulty: All Estimated Completion Time: 30 Minutes Step 1: Basic ElementsDocument14 pagesTutorial Details Program: Coreldraw 11 - X5 Difficulty: All Estimated Completion Time: 30 Minutes Step 1: Basic ElementsNasron ZubaidihNo ratings yet

- AE Instrumentenkunde 2022 GBDocument23 pagesAE Instrumentenkunde 2022 GBGeorgi GugicevNo ratings yet

- Astm D 2988 - 96Document3 pagesAstm D 2988 - 96o_l_0No ratings yet

- Settlement of A Shallow FoundationDocument6 pagesSettlement of A Shallow Foundationshehan madusankaNo ratings yet