Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Review The Armenian Revolutionary Movement The Development of Armenian Political Parties

Uploaded by

jamjar11Original Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Review The Armenian Revolutionary Movement The Development of Armenian Political Parties

Uploaded by

jamjar11Copyright:

Available Formats

The Armenian Revolutionary Movement: The Development of Armenian Political Parties through the Nineteenth Century by Louise Nalbandian

Review by: M. K. Krikorian The Slavonic and East European Review, Vol. 43, No. 100 (Dec., 1964), pp. 224-227 Published by: the Modern Humanities Research Association and University College London, School of Slavonic and East European Studies Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4205632 . Accessed: 26/11/2013 17:08

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Modern Humanities Research Association and University College London, School of Slavonic and East European Studies are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Slavonic and East European Review.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 86.3.188.134 on Tue, 26 Nov 2013 17:08:13 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

224

THE

SLAVONIC

REVIEW

Revolutionary Movement:The Development Nalbandian, Louise. TheArmenian University of theNineteenth Century. of Armenian PoliticalPartiesthrough California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles, Cambridge University Press, London, I963. ix + 247 pages. Bibliography. Index. a San Franciscan of Armenian origin 'and a Miss L. NALBANDIAN, permanent Research Associate in the Near Eastern Center, University of California, Los Angeles, has produced a study of the development of Armenian political parties in the igth century, which is the first work of its kind in English. The Armenian liberating movement started at the very moment when in I375 the kingdom of Cilician Armenia was ruined by the Mamluiks. The last king, Lewon VI, was captured and taken to Egypt and having been saved by ransom, wandered through Europe trying to gain support for the restoration of his throne. Thus Lewon VI came to be the founder of a movement which hoped to free Christian Armenia from the hands of the Muslims with the help of Christian Europe. In the middle of the Igth century a fundamental change came about in the Armenian liberation movement. Whereas before the Armenians hoped to be saved through the aid of Christian powers, now they were convinced that revolutionary activity was necessary for the freedom of Armenia. This change was the result of the contact of the Armenian intellectuals with European revolutionary ideas. The West-Armenians were inspired by the history and atmosphere of France, while the East-Armenians were influenced by Russian revolutionaries. The reforms for western Armenia (the eastern provinces of Anatolia) which were promised at the Congress of Berlin (I878) were a further factor which stimulated the organisation of political parties. Thus there came into existence the Henchakian Revolutionary Party (I887), which in I909 was named the Social Democrat Henchakian Party, and the Armenian Revolutionary Federation (i890). These parties used bloody and revolutionary methods to hasten the promised reforms. Eventually, on I October I896, the Ottorman government issued an imperial decree proclaiming some reforms in the administration of Eastern Anatolia which were suggested by a European Commission. These reforms were only partly respected and only for a short time, until about I908 when the Young Turks came into power. Miss Nalbandian's study is devoted to the history of the parties menRevolutionary Movement, tioned above. The work is entitled The Armenian but until 1920 the Armenians did not have 'a revolutionary movement' like France or Russia, or like Greece and Bulgaria. They carried out daring actions of a revolutionary character in courageous self-defence or revenge. A revolutionary movement would have been almost impossible to organise because firstly historical Armenia was large and divided among the Ottomans, Russians and Persians; secondly the Armenians of Eastern Anatolia, although a prominent racial element, did not constitute the majority of the population; and thirdly, in spite of the fact that, generally speaking, the Armenians were a prosperous and

This content downloaded from 86.3.188.134 on Tue, 26 Nov 2013 17:08:13 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

REVIEWS

223

industrious people, they lacked strong financial resourcesand manpower. Finally, they did not enjoy the permanent support of a resolute foreign power. In the first two chapters, 'An Outline of Armenia's Struggle for Freedom' and 'The Ideological Background and Sources of the Armenian National Awakening', the author has introduced the reader to the history of the Armenian political parties, but the various geographical, historical, cultural and ideological notes are not well integrated and as a result give a confused impression. In the third chapter the story is more interesting and develops smoothly. 'Revolutionary Activity in Turkish Armenia, I860-I885' depicts the Armenian uprisings in Zeytun (now Suleymanlh), Van and Erzurum, and the unions which had political interests and preceded the later parties. These societies were: The Union of Salvation in Van (I872), the Black Cross Society, also in Van (I878) and the Protectors of the Fatherland in Erzurum (i 88i). The fourth chapter gives an historical survey of the Armenakan Party (I885-96) which was organised in Van by the students of Mkrtich Porthugalian (I848-I92I), a renowned intellectual from Istanbul. The purpose of the party was to 'win for the Armenians the right to rule over themselves through revolution'. Since I885 Porthugalian himself had been in Marseilles where he published (i August i885) the journal Armenia,which became the organ of the Armenakan party. The Armenakans were involved in revolutionary activity in I 889 when they imported fire-armsfrom Persia to Van, and in I896 when they resisted oppression and massacre by the Turks. Chapter five gives the history of the Henchakian Party from I887 to I896. It was founded by East-Armenian students at Geneva in August I887; its leader was Awetis Nazarbekian (named also Nazarbek or Lerentz) one of whose companions was his fiancee, Mariam Vardanian (known as Maro), a former member of a Russian secret revolutionary group in St Petersburg. From a social point of view the party was Marxist socialist and politically its aim was the restoration of the independence of Turkish Armenia by outside help and through inside revolutionary activity. The party's organ was the journal Henchak(The Bell) which first appeared in November I887, in Geneva. The methods of administration, propaganda and terror followed the Russian NarodnayaVolya,and in December i89I the party joined the Oriental Federation of Macedonian, Albanian, Cretan and Greek revolutionaries in order to pursue their cause on a broad front. On I5 July I890 the Henchaks demonstrated at Kum Kapu, where the Armenian Patriarchate was and still is located, 'to awaken the maltreated Armenians and to make the Sublime Porte fully aware of the miseries of the Armenians'; in August I 894 they led the open and armed resistance of Sasun (now Kabilcevaz) against the Kurdish and Turkish chiefs who continued to claim heavy protection tributes; on 30 September I895 they protested and demonstrated at Babi Ali, Istanbul, against the delay in instituting the reforms in the eastern provinces, and on I2 October i 895 they led a rebellion in Zeytun which lasted four months and was only concluded on the intervention of the European powers. These revolutionary activities of the Henchaks forced the Ottoman government to carry out the

This content downloaded from 86.3.188.134 on Tue, 26 Nov 2013 17:08:13 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

226

THE

SLAVONIC

REVIEW

reforms promised at the Congress of Berlin, but on the other hand they excited the anger of the Turks. In chapter six the author describes the 'Revolutionary Activities among the Armenians of Russia, I868-I890'. Here we learn about the revolutionary groups which came to the defence of TurkishArmenia. These were: the Goodwill Society of Alexandropol (Leninakan), Russian Armenia, which was founded in i868; the Bureau of the Devoted to the Fatherland, organised in the Medz Karakilise village of Alexandropol on 20 June 1874; the committee of Narodnaya Volyaformed at Tiflis and consisting of Georgians and Armenians, which in i88i-2 had its own Armenian circle; an anonymous society in Erevan which acted 'during the eighties'; the secret society Strength in Karabagh; the Union of Patriots founded at Moscow in the spring of I882, and the Young Armenia Society established in Tiflis under the leadership of Christaphor Michaelian in the winter of I889. These organisationswere inspired by the successfulrevolutions of the Balkan peoples. Miss Nalbandian comments: 'The successful revolutions in Greece and Bulgaria helped to convince Russian Armenian revolutionaries that the Armenians could also be liberated from the Ottoman Empire. They saw in the Balkans the beneficial results of revolution and urged in their writings that the Armenians use the same methods to achieve

immediateindependence' (p. 149).

The last chapter is entitled 'The Armenian Revolutionary Federation or Dashnaktsuthiun, I890-I896'. (Throughout the chapter, pp. I5I-78, the word 'Federation' in the headings is 27 times misprinted as 'Foundation'.) This strong party was founded at Tiflis in summer I890 by Christaphor Michaelian (I859-I905), Stephan Zorian or Rostom (I867-I9:19) and Simon Zawarian (i866-i 9I3). The Dashnaks were socialist Marxists, and using political means they pursued 'the political and economic freedom of Turkish Armenia'. In their programme and methods they were very close to the Henchakians, in fact at the beginning the two parties were united for a short while. The Dashnaks published a newspaper called Droshak (The Flag) and they achieved close relations with the Young Turks and Christian Balkans. The climax of their indiscreet activity was the siege of the Ottoman Bank at Galata on 26 August I896, the purpose of which was to compel the European powers to put into effect the administrative reforms of Turkish Armenia. This demonstration cost the lives of more than 6,ooo Armenians. The party continues to exist today, but since I920-I it has abandoned socialism and is engaged in an anticommunist campaign. At the end of the study, the author concludes: 'It can be said of them without reservationthat they worked at restoring the honour of their people and they believed as passionately as did their fifthcentury ancestors who fought at Awarayr: "We die as mortals, that we through our death may be placed among those who are immortal"' (p.i 85). Although Miss Nalbandian is not an historian, nevertheless she is a successful portrayer of history, and her book is a very useful and comprehensive account of the activities of the Armenian revolutionary groups and parties from I86o to I896. In compiling her work, the author has made

This content downloaded from 86.3.188.134 on Tue, 26 Nov 2013 17:08:13 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

REVIEWS

227

use of some manuscript theses and of many printed documents and books in Armenian and European languages. Unfortunately she has neglected the archive materials of Europe, and also the Turkish sources almost completely. Nevertheless, hers is a valuable book which provides the English reader with an impartial short history of the Armenian revolutionary movement, and one hopes that Miss Nalbandian will now carry her researches still further.

Vienna

M. K.

KRIKORIAN

Adams,ArthurE. Bolsheviks in theUkraine, TheSecond I9I8-I9I9. Campaign

Yale University Press, New Haven, Conn., and London, ix + 440 pages. Index. Maps. Bibliography.

I963.

THE Russian civil war, climax of the great revolutionary crisis on the outcome of which depended the future shape of Russian society, is scarcely, if at all, inferior in historical importance to the October revolution itself. Yet comparatively little has been published on the subject in the English language: any addition, therefore, to the information made available to the student of the period is to be warmly welcomed. The Russian civil war, as is well known, presents a bewildering kaleidoscope of rapidly shifting fronts, of military leaders, governments, parties, aspirations, occupations and interventions, in which even the line between 'White' and 'Red' was not always clearly drawn. One of the most troubled regions in this second 'Time of Troubles' was, of course, the Ukraine. Here, the revolutionary events of February and October were superimposed on the traditional tensions created by age-old aspirations for autonomy, by the rivalries of khokhol and katsap,cossack and peasant, peasant and proletarian, Ukrainian, Pole and Jew, of right bank and left, the men of Kiev and the men of Kharkov. Moreover, as one of the major granaries of Europe, the Ukraine in I9 I8 was of vital importance both to the blockaded central powers (and hence, obversely, also to the embattled Entente) and to the grain-starved bolsheviks of the industrial north. The operation of these and other forces (not least amongst them the Ukrainian peasant's healthy views of his own interests) made the Ukraine, for a time, one of the cockpits of struggling Europe. It is with two loosely connected incidents of the 'strugglefor the Ukraine' that the present volume is primarily concerned. The first of these involves the activities of ataman Grigor'yev, a military adventurer 'with remarkable capacities for vodka and fighting', who gained spectacular if ephemeral successes in the southern Ukraine, and, for a short time, held a kind of balance in the Ukraine between the bolsheviks and their opponents. Like his better known and more idealistic contemporary and rival batko Makhno, he found himself, thanks to the strength of his peasant-partisan detachments, placed in a position where, whilst none of the major parties in the civil war either could or would wholly trust him, none would readily incur his enmity. Potentially, the cossack-freebooter was a useful temporary

This content downloaded from 86.3.188.134 on Tue, 26 Nov 2013 17:08:13 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

You might also like

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5795)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Romance of Alexander The GreatDocument198 pagesThe Romance of Alexander The Greatjamjar11No ratings yet

- Netaji Papers Revealed: What Happened To The Money Deposited in The Azad Hind Bank?Document12 pagesNetaji Papers Revealed: What Happened To The Money Deposited in The Azad Hind Bank?Kunāl Majumder100% (1)

- Hospital Furniture and Equipment - Product ListDocument4 pagesHospital Furniture and Equipment - Product ListStrongman MedlineNo ratings yet

- Burger SauceDocument1 pageBurger Saucejamjar11100% (1)

- The End of Israeli Democracy - Foreign AffairsDocument9 pagesThe End of Israeli Democracy - Foreign Affairsjamjar11100% (1)

- الحسن و الحسينDocument156 pagesالحسن و الحسينjamjar11No ratings yet

- Evolving Wave of Terrorism and EmergenceDocument270 pagesEvolving Wave of Terrorism and Emergencejamjar11No ratings yet

- Does Jordans Anti Corruption CommissionDocument7 pagesDoes Jordans Anti Corruption Commissionjamjar11No ratings yet

- Michael Riffaterre - Poetic Language - Signo - Applied Semiotics TheoriesDocument6 pagesMichael Riffaterre - Poetic Language - Signo - Applied Semiotics Theoriesjamjar11No ratings yet

- Historical Discourse by CoffinDocument4 pagesHistorical Discourse by Coffinjamjar11No ratings yet

- Araceli, PalawanDocument2 pagesAraceli, PalawanSunStar Philippine NewsNo ratings yet

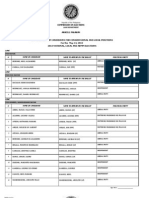

- Caloocan-1st - District (Election 2019 Vote)Document2 pagesCaloocan-1st - District (Election 2019 Vote)Jhon Paulo MazoNo ratings yet

- 007 Harshal Buildcon LLP 11.05.2023Document1 page007 Harshal Buildcon LLP 11.05.2023yogesNo ratings yet

- Padron HDocument205 pagesPadron HJuan Carlos MoralesNo ratings yet

- Speech - Results AnnouncementDocument5 pagesSpeech - Results AnnouncementMalawi2014No ratings yet

- Nawae Tally - 15 July 2022Document4 pagesNawae Tally - 15 July 2022Quinton NickNo ratings yet

- Solicitation Letter Cong. AmbenDocument4 pagesSolicitation Letter Cong. AmbenShaine Cariz Montiero SalamatNo ratings yet

- "The Philippines" in Political Parties and Democracy: Western Europe, East and Southeast Asia 1990-2010Document19 pages"The Philippines" in Political Parties and Democracy: Western Europe, East and Southeast Asia 1990-2010Julio TeehankeeNo ratings yet

- Global Strategy Group - NM AG Poll MemoDocument1 pageGlobal Strategy Group - NM AG Poll MemoAnonymous SHkKTf50yNo ratings yet

- List of India Governors As On October, 2017Document1 pageList of India Governors As On October, 2017Nagarjuna surepalliNo ratings yet

- Lubang, Occidental MindoroDocument2 pagesLubang, Occidental MindoroSunStar Philippine NewsNo ratings yet

- Lec6 All India Muslim LeagueDocument9 pagesLec6 All India Muslim LeagueIss AaqNo ratings yet

- State-Wise List of CM and GovernorDocument4 pagesState-Wise List of CM and GovernorraviNo ratings yet

- Coup de Grâce MugabeDocument78 pagesCoup de Grâce MugabeL'Homme De GammeNo ratings yet

- 2014 Results Form 20 PDFDocument38 pages2014 Results Form 20 PDFSheik SirajahmedNo ratings yet

- Spotlight: Always in TheDocument1 pageSpotlight: Always in TheDhanush KumarNo ratings yet

- AP Gov Vocab Unit 2-1Document2 pagesAP Gov Vocab Unit 2-1ancientblackdragonNo ratings yet

- 12th Zoology Full Study Material Tamil Medium 2022-23Document140 pages12th Zoology Full Study Material Tamil Medium 2022-23Shatheesh Julius100% (1)

- Dravidian MovementDocument9 pagesDravidian MovementRAJAKUMARAN S RNo ratings yet

- 2012 Presidential and Congressional Primary DatesDocument4 pages2012 Presidential and Congressional Primary DatesSunlight FoundationNo ratings yet

- Ba'athismDocument10 pagesBa'athismRodrigo BacelarNo ratings yet

- The Dallas Morning NewsDocument0 pagesThe Dallas Morning NewsSatoshi SugiyamaNo ratings yet

- Rameshwar Prasad CaseDocument165 pagesRameshwar Prasad Casesiddharth pandeyNo ratings yet

- THE Curious Case of Zimbabwe'S Generals: Do You Want To Advertise?Document10 pagesTHE Curious Case of Zimbabwe'S Generals: Do You Want To Advertise?Managing EditorNo ratings yet

- 186 Education Unit 8 PGTRB Study MaterialDocument5 pages186 Education Unit 8 PGTRB Study MaterialSANKAR VNo ratings yet

- Burma and Southeast Asian RegionalismDocument45 pagesBurma and Southeast Asian RegionalismkerrypwlNo ratings yet

- Scenes From The Last Days of Communism in West Bengal by INDRAJIT HAZRADocument22 pagesScenes From The Last Days of Communism in West Bengal by INDRAJIT HAZRAdonvoldy666No ratings yet

- 07 Chapter1Document19 pages07 Chapter1zakariya ziuNo ratings yet