Professional Documents

Culture Documents

K AMDHENU222

Uploaded by

vishalkraoOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

K AMDHENU222

Uploaded by

vishalkraoCopyright:

Available Formats

KAMDHENU DAIRY Why do you maintain that FA milk is more profitable than any of one other product you

produce? Professor Puranik asked Mr. Mathias, the general manager of the Kamdhenu dairy. Mr. Mathias replied, This is because we incur very little overheads for this p roduct as compared to others; for instance we have no advertising or other promotional expenditure for this product. The production process is very simple and the product has assured success. However, you can study our costs for all the products we produce and satisfy yourself about the validity of my statement. I am sure you will come to the same conclusion as I have reached after many years of experience in the industry. This was the discussion that took place between Mr. Mathias and two professors of a leading Management institute. In April 1964 the two professors visited the dairy to study the problems it had faced concerning the supply of FA milk to the state Government of a large state in Western India. The Kamdhenu Dairy was located in Sanand, a small town on the railway line connecting loading cities in Western India. The dairy was started mainly to provide better marketing facilities to the farmer for marketing the milk they produced. In the year 1945 the state government of western state started a milk scheme for the supply of milk in a major city of the state. According to this scheme, milk was to be collected from the Kheda district in the city mentioned above. During the initial stages of the scheme the collection of milk was left to collectors. And private diaries with the result that very little of the increase in the price offered by the state government was received by the farmers. In order to get the benefit of increased prices, the farmers decided to start a union of milk producers and a central processing unit at Sanand. It was decided that this union would collect the milk from the farmers, pasteurized it and sell it to the State Government. A building and some old machinery belonging to the government of India was leased by the union, top start a pasteurizing unit at Sanand. This marked the beginning of the Kamdhenu Dairy. From June 1948, the dairy started pasteurizing about 250 litres of milk per day. The cooperative movement amongst milk producers became very popular, and the organization grew at a very rapid rate. In 1953 it was found that the state milk scheme could not accept all the milk collect by the union during the winter months. This was because the state scheme required that the state should be supplied more or less constant quantity of milk, while the production of milk in the Kheda District varied widely between the summer and the winter seasons. In winter the production was 250 % of the summer production. This left the Kamdhenu dairy with two alternatives: 1. Either to restrict drastically the collection of milk during the Winter months; or 2. To find alternative ways of consuming the surplus milk collected in winter months. The first alternative was not satisfactory, as the farmers wanted to be assured of a year round market for all he surplus milk they desired to sell. In order to assure the farmers a year round market, the management of Kamdhenu Dairy decided to construct a dairy factory to convert milk into milk products. It obtained assistance from UNICEF and the Government of New Zealand and with the investment of Rs. 50 lakhs a factory was put into operation from October 1955.

The opening of the dairy gave great incentive to milk production in the Kheda district. And the union was able to procure more and more milk each year. The progress of the union after the new factory was built is illustrated in Exhibit 1. The milk collected by the Kamdhenu Dairy was converted into the following main products: 1. FA milk for the state Milk Scheme. 2. Butter 3. Ghee 4. Skim Milk powder 5. Baby Food 6. Cheese Exhibit 2 gives the production processes for these products and the quantities in which they were produced during the financial year 1963-64. In early 1964 Mr. Shrivastava, the Asst. General Manager of the Kamdhenu Dairy attended a management development Programme organised by the management Institute already mentioned above. During this programme he discussed with a senior Professor of the Institute, the problem he faced in deciding the quantity of the FA milk that should commit to supply the state milk scheme. The difficulty had arisen because of the variation and uncertainty involved in the procurement of raw milk. The Professor asked him to contact Professors S. Purnik and D.K. Mehta, who were interested in problems of this nature. In April 1964 the two Professors visited the Kamdhenu Dairy and met Mr. Mathias and Mr. Shrivastava to understand the nature of the problem. Mr. Shrivastava explained the problem as under: Milk supply from our societies is at its minimum in the month of June and reached its maximum in December-January. Though this variation is known, it is impossible to predict with certainty the quantity of milk that we will be able to procure in the lean and the peak periods. Ideally we would like to vary our supply of FA milk to the state Milk Scheme according to the variation of our milk procurements. Unfortunately our contract terms do not permit us to do so. According to the contract we have to supply them with more or less a uniform quantity of FA milk throughout the year. In case we fail to supply the requisite quantity we have to pay a penalty at the rate of 8 Rs. for every litre that falls short of the contracted quantity. You must remember that FA Milk is the most profitable product that we make. In case we contract too little too small a quantity with the state because of the fear of not being able to supply it in summer we lose profit. On the other hand if we contract too large a quantity we have to pay a penalty. In a view of this, I would like to know what is the optimum quantity that I should settle for.

At this point, Professor Puranik asked Mr. Mathis the question stated at the beginning of the case. As the question of profitability of the various products was very important in this problem, the two professors decided to examine the cost structure of the various products and ascertain the profitability of each product. Mr. Mathis suggested that Mr. Shrivastava, Mr. Ramaswami, the accountant, and the two Professors get together, so that Mr. Ramaswami could explain the cost structure of various products. At a subsequent meeting, Mr. Ramaswami presented the statement given in Exhibit 3 and made the following comments. We find that our contention that FA milk is the most profitable product is borne out of facts. You will notice that in other products, except for whole milk powder and FA milk, we are either breaking even or losing money. Consider cheese for example, Mr. Shrivastavas favourite pro duct. In estimating the profitability of this product, I have not accounted for the expenditure that we incurred for development of this product and yet we are losing heavily on cheese, I am wondering why we should not drop this product. As for baby food, we do not make any money, but as Mr. Mathias says. We are a cooperative society and must look for the welfare of people in general, and should not merely concentrate on profit. For your information, this is our prestige product. However, I must say the concept of defining alternatives as I have used in the statement was something which I learned from discussions with the professors. Formerly we use to evaluate profitability of products individually rather than of combinations which is the correct way of looking at things from a technical as well as accounting point of view. At this point, Professor Puranik commented, we are glad that you have started considering product combinations rather than i ndividual products. However, we are not sure as to how far the cost you have worked out is relevant for deciding the cost profitable product mix. Mr Shrivastava said, Mr Ramaswami, the management bous always talk of relevant costs. At the management development programme they use to tell us that while choosing amongst the alternatives, one should consider only the costs that had to be incurred in future and not worry about the sunk cost. As they said, let bygones be bygones. I do not see how you can be wrong in your findings. You have not missed any relevant costs. However, let the professor scrutinise the cost statements and advise us. He said further to the professors I am interested in finding out the optimum product mix. Today we are enjoying a sellers market, and have no difficulty in selling all we produce. Our whole milk powder is purchased by the government of India for defence needs, our cheese has good demand and I can hope to sell cheese at a rate of thousand tons per year without any difficulty. In short, marketing is no problem for the present and I think the conditions will remain the same for some time to come. Our only constraints are production capacity (listed in Exhibit 5), the availability of raw milk and contractual obligation of supplying FA milk to state milk scheme at a rate of 75,000 litres a day. You may perhaps be aware that we have a big programme for expansion. We would like to know the direction in which we should expand. The professors were considering what they should do next.

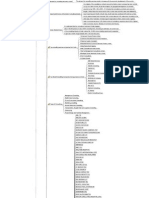

Table illustrating Number of societies Number of farmer progress made by the members of the union from 1955-56 society to 1962-63 Year ending 31st march Position before new dairy was built 1955-56 64 22,828 Position after new dairy was built 1956-57 107 26,795 1957-58 130 29,003 1958-59 168 33,068 1959-60 167 40,181 1960-61 195 40,500 Position after the dairy was expanded for baby food and cheese 1961-62 219 46,400 1962-63 254 58,400

Share capital of the union (Rs)

Quantity of milk collected (Liters)

2,17,400 3,61,500 3,93,900 4,73,500 5,67,100 7,41,100 7,48,700 8,19,200

1,11,36,343 1,41,64,000 2,11,56,400 2,75,57,800 2,29,27,000 2,35,13,000 6,53,98,429 5,04,17,8112

You might also like

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Warhammer Fantasy Roleplay Price ListDocument80 pagesWarhammer Fantasy Roleplay Price ListConan Brasher100% (4)

- A Technopreneurship Study On Ricotta Cheese Repaired)Document101 pagesA Technopreneurship Study On Ricotta Cheese Repaired)recto_taro100% (1)

- Projects: Dairy Farms From Vision To SuccessDocument8 pagesProjects: Dairy Farms From Vision To SuccessAditya Kumar DwivediNo ratings yet

- Cinnabon Int'l Oreo Chillatta - May 2012Document14 pagesCinnabon Int'l Oreo Chillatta - May 2012Jean Carlo Villanueva GoyzuetaNo ratings yet

- 100cows Project Withtext For LearningDocument28 pages100cows Project Withtext For Learningumanshu3359100% (1)

- Uht (Ultra-High Temperature) Tecnology For Processing of Long Life Milk A Prospect in Nepal.Document32 pagesUht (Ultra-High Temperature) Tecnology For Processing of Long Life Milk A Prospect in Nepal.अशोक आचार्य100% (2)

- Powerful Forecasting With MS Excel SampleDocument257 pagesPowerful Forecasting With MS Excel SampleBiwesh NeupaneNo ratings yet

- Critical Ratio RetailDocument2 pagesCritical Ratio RetailvishalkraoNo ratings yet

- Critical Ratio RetailDocument2 pagesCritical Ratio RetailvishalkraoNo ratings yet

- Financial Management NotesDocument4 pagesFinancial Management NotesvishalkraoNo ratings yet

- Critical Ratio RetailDocument2 pagesCritical Ratio RetailvishalkraoNo ratings yet

- GM1Document2 pagesGM1vishalkraoNo ratings yet

- Derivative NotederivatibvesDocument1 pageDerivative NotederivatibvesvishalkraoNo ratings yet

- GM212Document2 pagesGM212vishalkraoNo ratings yet

- GM1Document2 pagesGM1vishalkraoNo ratings yet

- GMDocument2 pagesGMvishalkraoNo ratings yet

- GMDocument2 pagesGMvishalkraoNo ratings yet

- GMDocument2 pagesGMvishalkraoNo ratings yet

- Consulting CompaniesDocument1 pageConsulting CompaniesShekhar YadavNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Adobe Flex: - Vishal KuppiliDocument9 pagesIntroduction To Adobe Flex: - Vishal KuppilivishalkraoNo ratings yet

- 'Red Lines'. The Official Israeli Document For Food Consumption in Gaza Under SiegeDocument35 pages'Red Lines'. The Official Israeli Document For Food Consumption in Gaza Under SiegeHaitham SabbahNo ratings yet

- DAIRY Industry Performance Report - Jan - Dec 2015-1-1Document11 pagesDAIRY Industry Performance Report - Jan - Dec 2015-1-1Czarmel Anne CB100% (1)

- As 4709-2001 Guide To Cleaning and Sanitizing of Plant and Equipment in The Food IndustryDocument7 pagesAs 4709-2001 Guide To Cleaning and Sanitizing of Plant and Equipment in The Food IndustrySAI Global - APAC0% (1)

- 1000 Onethebluebo 00 UnseDocument142 pages1000 Onethebluebo 00 UnseMaria MarinaNo ratings yet

- Karnataka Cooperative Milk ProducersDocument9 pagesKarnataka Cooperative Milk ProducersPoirei Zildjian0% (1)

- 3 Ways To Milk A CowDocument6 pages3 Ways To Milk A CowredbananamoonNo ratings yet

- Precision Livestock Farming in India: Dr. Manjeet SinghDocument35 pagesPrecision Livestock Farming in India: Dr. Manjeet SinghNikhil AIC-SRS-NDRINo ratings yet

- 643 SolicoBrands CatalogueDocument49 pages643 SolicoBrands CatalogueNino KalandiaNo ratings yet

- 8cbc146702a517e-Intermodal Freight Terminal Feasibility Study - FinalDocument127 pages8cbc146702a517e-Intermodal Freight Terminal Feasibility Study - FinalArnas KnystautasNo ratings yet

- Jodhpur DairyDocument32 pagesJodhpur DairySandeep TanwarNo ratings yet

- PREFACE NewDocument5 pagesPREFACE Newrajeshsuthar390No ratings yet

- GCMMF (AMUL) CASE STUDY ANALYSISDocument9 pagesGCMMF (AMUL) CASE STUDY ANALYSISTushar RanaNo ratings yet

- Dairy Bull - 551BS01421 - Hilltop Acres D Kickstart ETDocument1 pageDairy Bull - 551BS01421 - Hilltop Acres D Kickstart ETJonasNo ratings yet

- Animal Production Management Livestock and PoultryDocument58 pagesAnimal Production Management Livestock and PoultryArminjhon CompalNo ratings yet

- Definition, Composition, Standards and Factors Affecting Quality of Paneer and ChhanaDocument18 pagesDefinition, Composition, Standards and Factors Affecting Quality of Paneer and ChhanaRonak RawatNo ratings yet

- 7 Business Presentation Foremost 101216081607 Phpapp01Document12 pages7 Business Presentation Foremost 101216081607 Phpapp01Ryan TayNo ratings yet

- Technical FeasibilityDocument1 pageTechnical FeasibilityVijay VoraNo ratings yet

- Term Report: Production Operation ManagementDocument16 pagesTerm Report: Production Operation ManagementZainab KashaniNo ratings yet

- Sbi Pre Sanction Inspection ReportDocument2 pagesSbi Pre Sanction Inspection ReportNavnath KadamNo ratings yet

- Govardhan Dairy FarmDocument14 pagesGovardhan Dairy FarmFaisal Mullaji0% (1)

- Dairy Development CorporationDocument2 pagesDairy Development Corporationprakashvet20No ratings yet

- Lactic Acid Fermentation and Yoghurt-Making Recipes: Warm UpDocument2 pagesLactic Acid Fermentation and Yoghurt-Making Recipes: Warm UpSANYI LORENA ROJAS LEÓNNo ratings yet

- Joyday Pricelist Update Q2 2023Document1 pageJoyday Pricelist Update Q2 2023Anjar Saputtra100% (1)

- On AmulDocument17 pagesOn Amulmurarimishra170% (1)