Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Common Childhood Fears by PETER MURIS, HARALD MERCKELBACH and RON COLLARIS (1997) - An Article

Uploaded by

bvromanOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Common Childhood Fears by PETER MURIS, HARALD MERCKELBACH and RON COLLARIS (1997) - An Article

Uploaded by

bvromanCopyright:

Available Formats

Pergamon

Beh, r. Res. Ther. Vol. 35, No. 10, pp. 929-937, 1997 1997 ElsevierScienceLtd, All rights reserved Printed in Great Britain PII: S0005-7967(97)00050-8 0005-7967/97 $17.00 + 0.00

COMMON

CHILDHOOD

FEARS

AND

THEIR

ORIGINS

PETER MURIS, HARALD MERCKELBACH and RON COLLARIS

Department of Psychology, University of Maastricht, P.O. Box 616, 6200 MD Maastricht, The Netherlands

(Received 14 April 1997)

Summary--The present study examined rank orders and characteristics of childhood fears. A 'free option" approach ('What do you fear most?') deviated markedly from the fear rank order based on the Fear Survey Schedule for Children. A second aim of the study was to investigate the origins of prevalent childhood fears. In contrast to the results of Ollendick and King (1991, Behaviour Research and Therapy, 29, 117-123), conditioning was found to be the most commonly reported pathway related to exacerbation and onset of fears. Finally, special attention was given to the top intense fear in children, namely fear of spiders. Children who reported 'none', ~some' or "a lot' of spider fear were compared with each other in terms of pathways. No differences between the three groups were found with respect to the frequency of modeling and information experiences. However, high fearful children more often reported conditioning experiences than low or moderate fearful children. ~" 1997 Elsevier Science Ltd

INTRODUCTION Studies on childhood fears have predominantly relied on surveys that list a broad range of potentially fear-provoking stimuli. A widely used instrument for this purpose is the revised version of the Fear Survey Schedule for Children (FSSC-R; Ollendick, 1983). The FSSC-R asks children to indicate on three-point scales ('none', 'some', 'a lot') how much they fear specific stimuli or situations. Studies employing the FSSC-R consistently found that prevalent fears of children are nearly always related to dangerous situations and physical harm. More specifically, FSSC-R studies reported the following rank order for common childhood fears: (1) not being able to breathe; (2) being hit by a car or truck; (3) bombing attacks; (4) getting burned by fire; (5) falling from a high place; (6) burglar breaking into the house; (7) earthquake; (8) death; (9) illness; and (10) snakes (e.g. Ollendick, King & Frary, 1989; Ollendick, Yule & Ollier, 1991; Ollendick & King, 1994). So far, only one study has directly examined the origins of common childhood fears (Ollendick & King, 1991). That study evaluated to what extent Rachman's (Rachman, 1977, 1991) theory of fear acquisition can be applied to the ten most common FSSC-R fears. Children who reported 'a lot' of fear to FSSC-R items such as 'not being able to breathe', 'being hit by a car or truck', and so forth, were given a short questionnaire which asked them to indicate: (1) whether they remembered having a bad or frightening experience with this item (i.e. conditioning); (2) whether their parents, friends, or other acquaintances reacted with a fear response to this item (i.e. modeling); and/or (3) whether they had heard frightening things about this item from their parents, teachers, friends, television, and so on (i.e. negative information). Ollendick and King (1991) found that the majority of children attributed their fear to negative information (i.e. 88.8% of the children reported such experiences). Modeling and conditioning events were less often mentioned by the children (i.e. 56.2 and 35.7%, respectively). An important limitation of the Ollendick and King (1991) study is that it only asked children whether they had experienced information, modeling, and/or conditioning events in connection with the feared stimulus or situation. Children were not explicitly asked to what extent such experiences actually had contributed to the onset and/or severity of the fear. Thus, Ollendick and King employed a broad definition of etiological pathways, and this may have yielded inaccurate estimates of the role that these pathways play in the origins of fears (see, for a similar critique, Menzies & Clarke, 1994; Menzies, 1996).

929

930

Peter Muris et al.

Another critical point has to do with the instrument that Ollendick and King (1991) used to generate a fear rank order, namely the FSSC-R. Some authors have questioned the validity of this instrument. For example, McCathie and Spence (1991) suggested that a number of FSSC-R items (e.g. not being able to breathe, bombing attacks, getting burned by fire) do not measure actual fear, but rather reflect children's negative affective response to the thought of occurrence of such specific events. Therefore, it may well be the case that FSSC-R fear rank orders include items to which children have a negative attitude. In line with this, an exploratory study by Muris, Merckelbach, Meesters and Van Lier (1997) indicated that children's fear rank orders critically depend on the survey method that researchers use. In that study, fear rank orders were obtained along two different ways. One fear rank order was based on children's FSSC-R scores, whereas the other fear rank order was derived from what children reported as their most feared object (i.e. free option method). Both methods yielded quite different fear rank orders. That is, stimuli that figured high in one fear rank order, ranked relatively low in the other fear rank order. However, the Muris et al. (1997) study had one potential weakness: the question 'What do you fear most?' (i.e. free option method) was always asked after the children had completed the FSSC-R. It may well be the case that children's responses to the open question were affected by this sequence. For example, some children may have interpreted the open question as an invitation to come up with new items not covered by the FSSC-R. The current study further examined fear rank orders in children. As in the Muris et al. (1997) study, fear rank orders were obtained in two manners: (1) by administering the FSSC-R; and (2) by asking children 'What do you fear most?'. To avoid systematic carry-over effects, a counter-balanced procedure was followed: half of the children first completed the FSSC-R and then received the open question, whereas the other half had the reverse order (i.e. first free option, then FSSC-R). A second purpose of the present study was to assess to what extent modeling, negative information, and conditioning contribute to the development of common childhood fears. According to the non-associative model proposed by Menzies and Clarke (1995), these pathways are not required for most cases of fear acquisition. By this view, most childhood fears arise in the absence of negative experiences that are associated with the object of fear. Menzies and Clarke (1994), Menzies and Clarke (1995) and Menzies (1996) argue that previous research on fear acquisition has tended to classify any negative experience as a modeling, informational, and/or a conditioning event. This would have resulted in a significant overestimation of the three pathways of fear and an underestimation of non-associative (i.e. spontaneous) scenarios of fear acquisition. Therefore, in the present study, children were not only asked whether they had ever had modeling, information, and/or conditioning experiences in connection with their fear, but also to what extent such experiences had intensified their fear or had play a role in the actual onset of their fear. Particular attention was given to fear of spiders, which was found to be the top intense fear of children in our previous study (Muris et al., 1997). Furthermore, in order to examine whether certain characteristics and/or etiological pathways were unique for spider fear, high fearful children were compared with low and moderate fearful children.

METHOD Subjects The sample consisted of 129 children (74 boys; 55 girls) with ages ranging between 9 and 13 yr (M = 10.5, SD = 1.0). The children attended two regular schools in Echt, MiddleLimburg, the Netherlands. Assessment Fear Survey Schedule for Children--Revised. The FSSC-R (Ollendick, 1983; ~ = 0.96) is an 80-item self-report questionnaire. Children are asked to indicate their level of fear to various stimuli and situations on a three-point scale: 'none'; 'some'; or 'a lot'. These are scored 1, 2, and 3, respectively, and then summed over the 80 items to yield a total fear score varying between 80 and 240. Factor analysis of the FSSC-R has revealed five factors: fear of failure and criti-

C o m m o n c h i l d h o o d fears Table 1. FSSC-R based fear rank orders Fear Total sample (N = 129) 1. Not being able to breathe 2. Getting a serious illness 3. Bombing attacks/being invaded 4. Being hit by a car or truck 5, Fire/getting burned 6. Burglar breaking into house 7. Getting lost in a strange place 8. Falling from a high place 9. Death/dead people 10. Spiders Boys (n = 74) I. Not being able to breathe 2. Bombing attacks/being invaded 3. Getting a serious illness 4. Being hit by a car or truck 5. Fire/getting burned 6. Burglar breaking into house 7. Getting lost in a strange place Falling from a high place 9. Death/dead people 10. Snakes Girls (n = 55) 1. Not being able to breathe 2. Being hit by a car or truck 3. Getting a serious illness 4. Bombing attacks/being invaded Fire/getting burned 6. Burglar breaking into house Getting lost in a strange place 8. Spiders 9. Death/dead people 10. Falling from a high place Number of Ss rating 3: "a lot" 88 75 74 70 58 53 52 43 42 41 47 42 40 34 26 24 23 23 19 16 41 36 35 32 32 29 29 27 22 20 Percentage of sample 68.2 58.1 57.3 54.2 45.0 41.1 40.3 33.3 32.6 31,8 63.5 56.8 54.1 45.9 35.1 32.4 31.t 31.1 25.7 21.6 74.5 65.5 63.6 58.2 58.2 52.7 52.7 49.1 40.0 36,4

931

cism, fear of the unknown, fear of small animals, fear of danger, and medical fears. Studies have demonstrated that this factor structure can be generalized across children and adolescents in the United States (Ollendick, 1983), Australia (Ollendick et al., 1989), England (Ollendick et al., 1991), and The Netherlands (Oosterlaan, Prins, Hartman & Sergeant, 1995). Fear interview. This interview lasted for about 20 min and consisted of two parts. The first part began with the question 'What do you fear most?'. Following this, children were invited to describe several characteristics of their top intense fear. More specifically, they were asked to provide details about the intensity ('How much do you fear...?'; 1 = not at all; 10 = very much), level of interference ('How much does your fear of...disrupt your daily activities?'; 1 = not at all; 10 = very much), frequency of worry ('How much do you worry about...?'; 1 = not at all; 10 = very much), and reactions to the feared stimulus ('How do you react when you are confronted with...?'; with physical symptoms, negative thoughts, and avoidance behaviour rated in terms of 0 = absent and 1 = present). Furthermore, children were interviewed about the different pathways of fear acquisition with separate questions about modeling ('Do you know people who are also afraid of...?', 'Did this cause you to be more fearful?'), negative information ('Did you hear frightening things about...?', 'Did this cause you to be more fearful?'), and conditioning events ('Did you have a bad or frightening experience with...?', 'Did this cause you to be more fearful?'). In addition, children were explicitly asked to what extent these pathways were related to the onset of their fear ('How did your fear of...begin?'; modeling, negative information, conditioning experience, 'I don't know'). They also gave an estimate of the age of onset ('At what age did your fear of...start?'). The second part of the interview was concerned with fear of spiders. All questions of the first part (except for the 'onset' and 'age of onset' questions) were repeated in order to get a more precise picture of the characteristics and origins of spider fear.

Procedure

Children were assigned to two groups. Group 1 (n = 66; 37 boys and 29 girls) was first interviewed and then completed the FSSC-R, while group 2 (n = 63; 37 boys and 26 girls) followed the reverse order. Both groups were matched with respect to age.

932

Peter M u r i s et al. Table 2. Fear rank orders based on 'free option'

Fear Total sample (N = 129) I. Spiders 2. Being kidnapped 3. Predators The dark 5. Frightening movies 6. Snakes 7. Being hit by a car or truck Being teased Parents dying 10. Burglar breaking into house Boys (n = 74) 1. Spiders 2. Predators 3. Being hit by a car or truck Snakes 5. Burglar breaking into house Frightening movies The dark 8. Being teased Frightening dreams Operations Girls (17 = 55) 1. Spiders 2. Being kidnapped 3. Parents dying The dark 5. Frightening movies Thunderstorms 7. Being teased Bats Ghosts and spooky things Going to bed in the dark Making mistakes

Number of Ss 24 10 8 8 7 6 5 5 5 4 12 7 5 5 4 4 4 3 3 3 12 8 4 4 3 3 2 2 2 2 2

Percentage of sample 18.6 7.8 6.2 6.2 5.4 4.7 3.9 3.9 3.9 3.t 16.2 9.5 6.8 6.8 5.4 5.4 5.4 4.1 4. I 4.1 21.8 14.5 7.3 7.3 5.5 5.5 3.6 3.6 3.6 3.6 3.6

Number in FSSC-R rank order 10 2I 15 23 II 4 28 6 12 26 4 10 6 26 14 3l 18 14 8 13 20 40 27 51 32 32 74

Children completed the FSSC-R in their classrooms, while the interview took place in a separate room. Children were interviewed individually and the interviews were conducted by a trained research assistant. Children were told that their responses would remain confidential. RESULTS

Fear rank orders

The fear rank orders of children who first underwent the interview and then completed the FSSC-R were comparable to those of the children who had the reverse order: the correlation between the FSSC-R rank order of group 1 and that of group 2 was 0.97, P < 0.001, whereas the correlation between the free option based rank orders of group 1 and 2 was 0.68, P < 0.001. Thus, both types of fear rank orders appear to be relatively insensitive to carry-over effects. Therefore, the data of both groups were collapsed. Tables 1 and 2 present the top 10 fears as obtained by FSSC-R and free option method, respectively. It should be noted that the rank order derived from the FSSC-R (as determined by the percentage of children who gave the maximum rating; e.g. Ollendick et al., 1989) was highly similar to that found in other studies employing this questionnaire (Ollendick et al., 1989; Ollendick et al., 1991; Ollendick & King, 1994; Muris et al., 1997). The hierarchy obtained by asking the children what they feared most (see Table 2) included several items that also ranked high in the FSSC-R rank order (i.e. being hit by a car or truck, burglar breaking into house, and spiders). However, items such as being kidnapped, predators, frightening movies, and being teased were more often reported when employing the free option method. Clustering of prevalent fears that were reported with the free option method revealed that fear of animals was most frequently mentioned (n = 49), followed by fear of the unknown (n = 29), fear of danger and death (n = 22), medical fears (n = 9), and fear of failure and criticism (n = 8). Interestingly, these fear clusters fit the five FSSC-R factors. However, inspection of the mean scores on items of the separate FSSC-R factors revealed that children clearly scored highest on danger and death items (M = 2.1, SD = 0.4). Mean scores on items of the other fac-

C o m m o n c h i l d h o o d fears

933

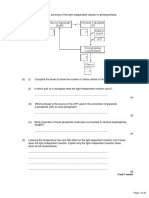

Table 3. Percentages of children who reported modeling, information, and conditioning experiences in all fears, the five most prominent fear clusters, and spider fear All fears (N = 129) Fear of animals (N = 49) Fear of the unknown (N = 27) Fear of danger and death (N = 22) 39.1 82.6 60.-"'0 4.3 47.8 34.8 0.0 41.0 31.8 27.2 Medical fears (N = 9) Fear of failure and criticism (N = 8) 62.5 87.5 75.--'-6 0.0 12.5 50...._00 0.0 0.0 50.0 50.-"'O Fear of spiders (N = 24)

Experiences Modeling experiences Information experiences Conditioning experiences Experiences intensifying fear Did modeling cause more fear? Did information cause more fear? Did conditioning cause more fear? Onset of fear Modeling Information Conditioning Don't know minent pathway is underlined.

49.6 87.8 61 .---7 3.8 35.1 45._._88 0.8 26.7 39.7 32.--"~

57.1 98,0 67."--33 0.0 38.8 53._._~1 0.0 28.6 44.9 26.""~

60.7 75.0 42.9 13.0 35.7 33.3 3.6 32.1 25.0 39.3

44.4 100.0 55.6 0.0 33.3 44._..~4 0.0 Ih I 44.4 44,"'4

87.5 100.0 7018 0.0 25.0 45..__.88 0.0 12.5 41.7 .-"--8 45

Note: Cochran's Q-tests revealed that in all cases, children's reports were not evenly distributed over the pathway options. The most pro-

tors were 1.5 (SD = 0.3) for animals, 1.5 (SD = 0.5) for medical items, 1.5 (SD = 0.4) for the unknown, and 1.4 (SD = 0.3) for failure and criticism. Thus, again, the fear rank order as derived from the FSSC-R appeared to be quite different from that obtained by the free option method.

Characteristics of common fears

The mean intensity of children's top intense fear was 6.5 (SD = 2.0). Percentages of the children who reported physical symptoms, negative thoughts, and avoidance behaviour when confronted with this fear were 66.4%, 80.5%, and 75.0%, respectively. The level of interference and worry about the top intense fear were 4.2 (SD = 2.3) and 4.3 (SD = 2.1), respectively.

Origins o]I common .&ars

Table 3 shows percentages of children who reported modeling, information, and conditioning experiences in connection with their most feared stimulus or situation. As can be seen in the top rows of the left column in this table, the vast majority (87.8%) reported that they had heard frightening things about their most feared stimulus or situation. The percentages of children who endorsed modeling and conditioning pathways were considerably lower: 49.6% and 61.1%, respectively. However, children indicated that not all these experiences had actually intensified their fear (i.e. played a role in the maintenance of fear). The percentages of children who reported experiences that made them more fearful were 3.8% for modeling, 35.1% for information, and 45.8% for conditioning (see middle rows of the left column in Table 3). Percentages were even more conservative when children were asked to what extent these experiences marked the onset of their fear: 39.7% ascribed the actual onset of their fear to a conditioning experience, 32.8% had no clear idea about how their fear began (32.8%), 26.7% reported an information pathway, and only 0.8% indicated that their fear began with a modeling experience (see bottom rows of the left column in Table 3). Inspection of the separate fear clusters revealed that conditioning was reported as the most frequent pathway for fear of animals, medical fears, and fear of failure and criticism. For these fear categories, a relatively high percentage of children indicated that a conditioning experience had caused them to be more fearful and/or that the onset of their fear was associated with such an experience. For fear of the unknown and fear of danger and death, the information pathway was most often reported. As to the age of onset, fear of animals began at an early age (M = 6.5 yr), whereas fear of danger and death and medical fears appeared relatively late (means being 8.5 and 8.3 yr, respectively). A considerable minority of children who mentioned spiders as their top intense fear (41.7%; see right column of Table 3) said that the onset of their fear was connected to a conditioning

934

Peter M u r i s et aL Table 4. Characteristics and pathways of fear in children who report "none', 'some', or 'a lot" of fear of spiders "None" fear of spiders (n = 43) 'Some' fear of spiders (n = 45) 4.0 (2.4) 2.4 (1.7) 1.7 (1.0) 36.9 36.9 67.4 'A lot' fear of spiders (n = 41) 6.4 (2.2) 3.1 (2.3) 3.3 (2.4) 63.4 56.1 95. I F or ~2 p

Characteristics Intensity Level of interference Frequency of worry Physical symptoms Negative thoughts Avoidance behaviour Origins Experiences Modeling experiences Information experiences Conditioning experiences Experiences intensifying fear Did modeling cause more fear? Did information cause more fear? Did conditioning cause more fear?

2.3 (1.8) 1.6 (1.3) 1.6 (I. 1) 15.9 18.1 45.4

37.9 7.4 16.2 20.3 13.1 24.4

< 0.001 < 0.005 < 0.001 < 0.001 < 0.005 < 0.001

75.0 95.5 18.2 0.0 20.5 2.2

76. I 93.5 37.0 6.5 21.7 30.4

90.2 92.7 63.4 2.4 34.1 41.5

3.8 0.3 18.4 3.3 2.6 19.0

NS NS < 0.001 NS NS < 0.001

Note: For all variables, the percentages of children reporting the characteristic or pathway are given, except for intensity, level of interference, and frequency of worry. For these characteristics, the mean score on a 10-point scale is shown.

event. Furthermore, a substantial proportion (45.8%) indicated that they did not know how their fear of spiders had started. Mean onset age for spider fear was 5.9 yr (SD = 3.5).

Origins of spider fear

T:le data of the second part of the interview were used to analyze the origins of the top inter~se childhood fear, i.e. fear of spiders, in more detail. Based on children's rating of FSSC-R item 25 (i.e. spiders), low fearful (n = 44), moderate fearful (n = 46), and high fearful (n = 41) groups were formed (see Table 4). As expected, the three groups differed significantly with regard to 'intensity of spider fear' [F(2,126) = 37.9, P < 0.001], level of interference caused by spider fear [F(1,126) = 7.4, P < 0.005], frequency of worry about spiders [F(2,126) = 16.2, P < 0.001], and reactions when confronted with a spider [Z2(2) = 20.3, P < 0.001 for physical symptoms; Z2(2) = 13.1, P < 0.005 for negative thoughts; and Z2(2) = 24.4, P < 0.001 for avoidance behaviour]. Analysis of the 'pathways of fear' revealed no differences between the three groups with respect to modeling and information experiences. However, ,~2 analyses revealed significant effects for conditioning experiences. As can be seen in Table 4, high fearful children reported more conditioning experiences with spiders than moderate and low fearful children [X2(2) = 18.4, P < 0.001]. Furthermore, a higher percentage of the high fearful children claimed that such conditioning experiences had made them more fearful of spiders [Z2(2)= 19.0, P < 0.001]. DISCUSSION In the current study, hierarchies of common childhood fears were obtained along two different ways. One fear rank order was based on the FSSC-R scores, whereas the other fear rank order was based on what children indicated as their most intense fear (i.e. free option method). In line with our previous study (Muris et al., 1997), important differences between both fear rank orders emerged. For example, whereas the FSSC-R indicated that fears of danger and death have the highest prevalence, the free option method suggested that fears of animals are the most frequent intense fears. Kirkpatrick (1984) demonstrated that in fear surveys among adult men and women, the precise technique that is used affects the outcome of the survey. The study by Muris et al. (1997), as well as the current study, demonstrates that much the same is true for fear surveys among children. It is difficult to determine whether the FSSC-R as a survey instrument is superior to the free option method. Both methods may have advantages. The free option method relies on a simple and straightforward question ('What do you fear most?') and it is plausible to assume that it gives a good picture of the stimuli or situations that are frightening for children. On the other

Common childhood fears

935

hand, the FSSC-R lists a number of items that may prime and remind children of their fears. Perhaps, then, research into the prevalence and origins of common childhood fears should combine both approaches (e.g. Kirkpatrick, 1984). The second purpose of the study was to examine the origins of common childhood fears. In general, conditioning was found to be the most commonly reported pathway. Only for certain types of fear (i.e. fears of the unknown and fears of danger and death), the information pathway was more prominent. Finally, a more finegrained analysis of the top intense fear in children, i.e. fear of spiders, was carried out. Pathways to fear of children who reported 'none', ~some' or ~a lot' of spider fear were compared with each other. No differences between the three groups were found with respect to the frequency of modeling and information experiences. However, conditioning experiences were more often endorsed by high fearful children than by low or moderate fearful children. All in all, the present study found a pattern of pathways that differed from that reported by Ollendick and King's (1991) study on the origins of prevalent FSSC-R fears. These authors found that a majority of children attributed the onset of their fear to the information pathway, whereas the current data suggest that conditioning is the most prominent pathway to common childhood fears. There are two factors that may account for these conflicting results. First of all, 9 out of 10 fears that were examined in the Ollendick and King study were fears of danger and death. It is intuitively plausible to assume that the information pathway plays an important role in this type of fear. Indeed, the present data also demonstrate that negative information was the most frequently endorsed pathway in children who reported fear of danger and death items as their top intense fear. Secondly, Ollendick and King simply asked children whether they had ever had modeling, information, and/or conditioning experiences with the feared stimulus. These researchers did not ask children whether such experiences had actually intensified their fear and/or had played a role in the onset of their fear. In line with the findings of Ollendick and King (1991), the present study found that children more often reported negative information than either conditioning or modeling experiences. However, the current results also suggest that with a more strict definition (i.e. did the experience exacerbate fear and/or mark the onset of fears), conditioning experiences are the dominant pathway. In the present study, surprisingly few children attributed the exacerbation and/or onset of their top intense fear to modeling. At first sight, this finding conflicts with the results of a previous study (Muris, Steerneman, Merckelbach & Meesters, 1996). In that study, fearfulness (as indexed by the FSSC-R) of children was found to be positively associated with fearfulness of the mother. More specifically, a linear association between FSSC-R scores and mothers' rating of expressing fears to their children was found. That is to say, children of mothers who never expressed their fears had the lowest FSSC-R scores, children of mothers who often expressed their fears had the highest FSSC-R scores, whereas children of mothers who sometimes expressed their fears scored in between. Note, however, that Muris et al. (1996) studied the influence of modeling on children's general level of fearfulness, whereas the present study examined the pathways of specific childhood fears. In other words, it may well be the case that modeling enhances general fearfulness in children, but plays a minor role in the acquisition of specific fears. As to the origins of the top intense fear of children, i.e. spider fear, the present results accord well with those of a clinical study by Merckelbach, Muris and Schouten (1996). In that study, 40.9% of a sample of spider phobic children ascribed the onset of their fear to a conditioning experience. Likewise, in the current study, 41.7% of the children who mentioned spiders as their most feared object, reported that a conditioning experience marked the onset of their fear. The comparison of low, moderate, and high spider fearful children provided further evidence for the role of conditioning in the acquisition of spider fear. Results showed that high fearful children more often reported conditioning experiences than did low or moderate fearful children. No differences between the three groups were found with regard to the information and modeling pathways. Other recent studies also found evidence to suggest that, in severe childhood phobias, conditioning plays a more prominent role than negative information (e.g. Milgrom, Mancl, King & Weinstein, 1995; King, Clowes-Hollins & Ollendick, 1997). Taken together, these find-

936

Peter Muris et al.

ings provide further support for Rachman's (Rachman, 1977, 1991) elaboration of the conditioning model. This conclusion is, of course, difficult to reconcile with the non-associative view of intense fears and phobias (Menzies & Clarke, 1995; see, for a more elaborated critique of the non-associative account, Merckelbach, De Jong, Muris & Van den Hout, 1996). According to this view, there is a continuity between childhood fears and adult phobic disorders, with the former arising spontaneously, i.e. without apparent traumatic event. In contrast to what one would expect on the basis of the non-associative view, the current data found that children often attribute their fear to conditioning experiences. Still, one could counter that such retrospective accounts may be fueled by the attributional style of fearful children rather than their actual experiences (e.g. Withers & Deane, 1995). Therefore, future studies should investigate the metatheoretical beliefs of children about fear acquisition and the extent to which causal attributions are validated by information provided by parents (see, for example, Kheriaty, Kleinknecht & Hyman, 1997 and Merckelbach et al., 1996). A final remark pertains to the severity of common childhood fears. Ollendick and King (1994) found that children's self-reports of fear were clearly associated with high levels of daily interference and distress. That is, 60% of the children indicated that their fear resulted in 'a lot' of distress. To a certain extent, the present study confirms the idea that common childhood fears are distressing. For example, a considerable percentage of the children reported physical symptoms (66.4%), negative thoughts (80.5%), and avoidance behaviour (75.0%) when confronted with their most feared stimulus or situation. However, the level of interference and frequency of worry were far from high, means on a 10-point scale being 4.2 and 4.3, respectively. To resolve this issue, future studies should investigate the clinical significance of childhood fears through the employment of interview schedules for anxiety disorders (e.g. the Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for Children; Silverman & Nelles, 1988) combined with a longitudinal set-up (i.e. multiple measure points in time). Only in this way, one can assess how stable and serious these fears are and to what extent they are a precursor of adult phobias.

Acknowledgement Teachers and staff of the 'Driepas' and the 'Pius X school' in Echt, The Netherlands are thanked for their participation in this study.

REFERENCES Kheriaty, E., Kleinknecht, R. A., & Hyman, J. E. (1997). Recall and validation of phobia origins as a function of a structured interview versus the Phobia Origins Questionnaire. Behavior Modification, in press. King, N. J., Clowes-Hollins, V., & Ollendick, T. H. (1997). The etiology of childhood dog phobia. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 35, 77. Kirkpatrick, D. R. (1984). Age, gender, and patterns of common intense fears among adults. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 22. 141 150. McCathie, H., & Spence, S. H. (1991). What is the revised Fear Survey Schedule for Children measuring? Behaviour Research and Therapy, 29, 495-502. Menzies, R. G. (1996). The origins of specific phobias in a mixed clinical sample: Classificatory differences between two origins instruments. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 10, 347 354. Menzies, R. G., & Clarke, J. C. (1994). Retrospective studies of the origins of phobias: A review. Anxiety, Stress, and Coping, 7, 305-318. Menzies, R. G., & Clarke, J. C. (1995). The etiology of phobias: A non-associative account. Clinical Psychology Review, 15.23-48. Merckelbach, H., Muris, P., & Schouten, E. (1996). Pathways to fear in spider phobic children. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 34, 935-938. Merckelbach, H., De Jong, P. J., Muris, P., & Van den Hout, M. A. (1996). The etiology of specific phobias: A review. Clinical Psychology Review, 16, 337-361. Milgrom, P., Mancl, L., King, B., & Weinstein, P. (1995). Origins of childhood dental fear. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 33, 313-319. Muris, P., Merckelbach, H., Meesters, C., & Van Lier, P. (1997). What do chilren fear most? Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiato,, in press. Muris, P., Steerneman, P., Merckelbach, H., & Meesters, C. (1996). The role of parental fearfulness and modeling in children's fear. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 34, 265-268. Ollendick, T. H. (1983). Reliability and validity of the revised Fear Survey Schedule for Children (FSSC-R). Behaviour Research and Therapy, 21,685-692. Ollendick, T. H., & King, N. J. (1991). Origins of childhood fears: An evaluation of Rachman's theory of fear acquisition. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 29. 117-123.

Common childhood fears

937

Ollendick, T. H., & King, N. J. (1994). Fears and their level of interference in adolescents. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 32. 635-638. Ollendick, T. H., King, N. J., & Frary, R. B. (1989). Fears in children and adolescents: Reliability and generalizability across gender, age, and nationality. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 27, 19-26. Ollendick, T. H., Yule, W., & Oilier, K. (1991). Fears in British children and their relationship to manifest anxiety and depression. Journal t~f Child Psychology and Psyehiatry, 32, 321-331. Oosterlaan, J., Prins, P. J. M., Hartman, C. A., & Sergeant, J. A. (1995). Vraeenlijst voor angst bit kinderen: Handleiding. [User's manual for the Dutch Fear Survey Schedule for Children--Revised (FSSC-R) ]. Lisse, The Netherlands: Swets & Zeitlinger. Rachman, S. J. (1977). The conditioning theory of fear acquisition: A critical examination. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 15, 375-387. Rachman, S. J. (1991). Neoconditioning and the classical theory of fear acquisition. Clinical Psychology Review, 11, 155173. Silverman, W. K., & Nelles, W. B. (1988). The anxiety disorders interview schedule for children. Journal Of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatrv, 27, 772-778. Withers, R. D., &Deane, F. P. (1995). Origins of common fears: Effects on severity, anxiety responses, and memories of onset. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 8,903-915.

You might also like

- Child Abuse Pocket Atlas, Volume 5: Child Fatality and NeglectFrom EverandChild Abuse Pocket Atlas, Volume 5: Child Fatality and NeglectNo ratings yet

- Perceived Safety: A Multidisciplinary PerspectiveFrom EverandPerceived Safety: A Multidisciplinary PerspectiveMartina RaueNo ratings yet

- How Serious Are Common Childhood Fears? by Peter Muris, Harald Merckelbach, Birgit Mayer, Elske Prins (2000) - An ArticleDocument12 pagesHow Serious Are Common Childhood Fears? by Peter Muris, Harald Merckelbach, Birgit Mayer, Elske Prins (2000) - An ArticlebvromanNo ratings yet

- The Development of Normal Fear: A Century of Research: Eleonora GulloneDocument23 pagesThe Development of Normal Fear: A Century of Research: Eleonora Gulloneashoori79No ratings yet

- Milgrom 1995Document7 pagesMilgrom 1995Bruno CordeiroNo ratings yet

- Fears and Phobias in Children: Phenomenology, Epidemiology, and AetiologyDocument10 pagesFears and Phobias in Children: Phenomenology, Epidemiology, and Aetiologykarin24No ratings yet

- Panic Attack Symptomatology and Anxiety Sensitivity in AdolescentsDocument10 pagesPanic Attack Symptomatology and Anxiety Sensitivity in AdolescentsBálint KapturNo ratings yet

- Origins of Fear of Dogs in Adults andDocument8 pagesOrigins of Fear of Dogs in Adults andKindred BinondoNo ratings yet

- Preschooler'S Fears: Changes During The Last Ten Years in Estonia (1993-2002)Document7 pagesPreschooler'S Fears: Changes During The Last Ten Years in Estonia (1993-2002)jsdjkfjNo ratings yet

- Separation AnxietyDocument14 pagesSeparation AnxietyzahradoukNo ratings yet

- Defenses in School Age Children: Children's Versus Parents' ReportDocument19 pagesDefenses in School Age Children: Children's Versus Parents' ReporttosheeNo ratings yet

- Children's Specific Fears: Care, Health and DevelopmentDocument10 pagesChildren's Specific Fears: Care, Health and DevelopmentLeonard MpezeniNo ratings yet

- The Developmental Epidemiology of Anxiety Disorders Phenomenology, Prevalence, and ComorbityDocument18 pagesThe Developmental Epidemiology of Anxiety Disorders Phenomenology, Prevalence, and ComorbityShirleuy GonçalvesNo ratings yet

- The Assessment of Normal Fear in Childre PDFDocument16 pagesThe Assessment of Normal Fear in Childre PDFNikola MiticNo ratings yet

- Din Copil Abuzat Parinte AbuzatorDocument16 pagesDin Copil Abuzat Parinte AbuzatorValentinaNo ratings yet

- Ordinary Magic Resilience Processes in Development.Document12 pagesOrdinary Magic Resilience Processes in Development.Altikardes_Mar_5520No ratings yet

- 2010 Article 64Document22 pages2010 Article 64Carlos Fernandez PradalesNo ratings yet

- Lit Review Resilience TheoryDocument27 pagesLit Review Resilience TheoryAnthony Solina100% (3)

- Shenton (2020) - Behaviour Management or Institutionalised Repression Children S Experiences ofDocument17 pagesShenton (2020) - Behaviour Management or Institutionalised Repression Children S Experiences ofJo HNo ratings yet

- Worry in Children Is Related To Perceived Parental Rearing and Attachment by Peter Muris Et Al. (2000) - An ArticleDocument11 pagesWorry in Children Is Related To Perceived Parental Rearing and Attachment by Peter Muris Et Al. (2000) - An ArticlebvromanNo ratings yet

- Resilience Processes in Development - MastenDocument12 pagesResilience Processes in Development - MastenRuxandra ZahariaNo ratings yet

- Assessing Attachment Security With The Attachment Q Sort Meta-Analytic Evidence For The Validity of The Observer AQS.1 May O4Document27 pagesAssessing Attachment Security With The Attachment Q Sort Meta-Analytic Evidence For The Validity of The Observer AQS.1 May O4Desi PhykiNo ratings yet

- Child Abuse & NeglectDocument10 pagesChild Abuse & NeglectStéphanie DWNo ratings yet

- And My Mama Said - . .: The (Relative) Parental Influence On Fear of Crime Among Adolescent Girls and BoysDocument27 pagesAnd My Mama Said - . .: The (Relative) Parental Influence On Fear of Crime Among Adolescent Girls and BoysliviugNo ratings yet

- Galvan, Hare, Voss, Glover y Casey 2007 Risk Taking and The Adolescent Brain PDFDocument7 pagesGalvan, Hare, Voss, Glover y Casey 2007 Risk Taking and The Adolescent Brain PDFSamuel Salinas ÁlvarezNo ratings yet

- Vinculação ParentalDocument23 pagesVinculação ParentalNeiler OverpowerNo ratings yet

- Research With Young ChildrenDocument11 pagesResearch With Young ChildrenMeyLingNo ratings yet

- Metode Dan Hasil Jurnal Abnormal m8Document10 pagesMetode Dan Hasil Jurnal Abnormal m8Han HanNo ratings yet

- Examining Fears of Turkish Children and Adolescents With Regard To Age, Gender and Socioeconomic StatusDocument6 pagesExamining Fears of Turkish Children and Adolescents With Regard To Age, Gender and Socioeconomic StatusistinengtiyasNo ratings yet

- Multiple Determinants of Externalizing Behavior in 5-Year-OldsDocument15 pagesMultiple Determinants of Externalizing Behavior in 5-Year-OldsGerasim HarutyunyanNo ratings yet

- Paco Perez StudyDocument21 pagesPaco Perez Studygdlo72No ratings yet

- Manuscript UvA DAREDocument60 pagesManuscript UvA DAREMaria Carmela DomocmatNo ratings yet

- Evans 2013Document58 pagesEvans 2013Risky RamadhanNo ratings yet

- Gull One 2000Document15 pagesGull One 2000Maria SteriopolNo ratings yet

- Sex Differences Are Not Attenuated byDocument40 pagesSex Differences Are Not Attenuated byNolber C ChNo ratings yet

- LiebowitzDocument10 pagesLiebowitzRalucaButaNo ratings yet

- Bullatschool Jof Child Ps 1994Document22 pagesBullatschool Jof Child Ps 1994Vanesa CarpioNo ratings yet

- 01 JOHNSON-The Assessmen T andDocument2 pages01 JOHNSON-The Assessmen T andDescubrámonosNo ratings yet

- Survey OverconfidenceDocument28 pagesSurvey OverconfidenceBianca UrsuNo ratings yet

- Fears - in - Adolescence - 2009Document17 pagesFears - in - Adolescence - 2009fatimaramos31No ratings yet

- Running Head: Conditioning Theory and The Development of AnxietyDocument53 pagesRunning Head: Conditioning Theory and The Development of AnxietyABCNo ratings yet

- Journal of Anxiety Disorders: Ann E. Layne, Debra H. Bernat, Andrea M. Victor, Gail A. BernsteinDocument7 pagesJournal of Anxiety Disorders: Ann E. Layne, Debra H. Bernat, Andrea M. Victor, Gail A. BernsteinMelina Defita SariNo ratings yet

- Deception in Experiments Revisiting The Arguments in Its DefenseDocument35 pagesDeception in Experiments Revisiting The Arguments in Its DefenseAnonymous yVibQxNo ratings yet

- The Development of Early Pro Files of Temperament: Characterization, Continuity, and EtiologyDocument18 pagesThe Development of Early Pro Files of Temperament: Characterization, Continuity, and Etiologyantoniapopovici466No ratings yet

- Análisis Dimensional Coping Strategy Indicator (CSI)Document11 pagesAnálisis Dimensional Coping Strategy Indicator (CSI)Hector LezcanoNo ratings yet

- Cognitive Mechanisms Underlying Lying To Questions: Response Time As A Cue To DeceptionDocument20 pagesCognitive Mechanisms Underlying Lying To Questions: Response Time As A Cue To DeceptionSergio Blanes CáceresNo ratings yet

- Fear-Appeals in Social MKTDocument26 pagesFear-Appeals in Social MKTAlbi PanatagamaNo ratings yet

- Risk Assesment CARASDocument23 pagesRisk Assesment CARASgeaninalexaNo ratings yet

- Agresiveness in ChildrenDocument13 pagesAgresiveness in ChildrenPsihoterapeut Alina VranăuNo ratings yet

- International Journal 2Document7 pagesInternational Journal 2carinta yuniarNo ratings yet

- Children's Prepared and Unprepared Lies: Can Adults See Through Their Strategies?Document15 pagesChildren's Prepared and Unprepared Lies: Can Adults See Through Their Strategies?Alina UngureanuNo ratings yet

- (Cut Reading Text) Bayer - Bullying, Mental Health and Friendship in Australian Primary School ChildrenDocument2 pages(Cut Reading Text) Bayer - Bullying, Mental Health and Friendship in Australian Primary School Childrenphamanhtu100203patNo ratings yet

- PEER Stage2 10.1136 Bjo.2008.149815Document21 pagesPEER Stage2 10.1136 Bjo.2008.149815Ana NietoNo ratings yet

- Aggression and The Development of Delinquent Behaviour in ChildrenDocument6 pagesAggression and The Development of Delinquent Behaviour in ChildrenКовачевић ЈасминаNo ratings yet

- Externalizing Behavior Problems in Young ChildrenDocument12 pagesExternalizing Behavior Problems in Young ChildrenZee ZeNo ratings yet

- 2018 - A Meta-Analysis of The Prevalence of Child Sexual Abuse Disclosure in Forensic SettingsDocument14 pages2018 - A Meta-Analysis of The Prevalence of Child Sexual Abuse Disclosure in Forensic SettingsZayne CarrickNo ratings yet

- CARE ManualDocument59 pagesCARE ManualKorn IbraNo ratings yet

- Journal of Anxiety Disorders: Kathrin Dubi, Silvia SchneiderDocument10 pagesJournal of Anxiety Disorders: Kathrin Dubi, Silvia Schneiderkarin24No ratings yet

- Detection of Malingering during Head Injury LitigationFrom EverandDetection of Malingering during Head Injury LitigationArthur MacNeill Horton, Jr.No ratings yet

- Evidence of Harm: Mercury in Vaccines and the Autism Epidemic: A Medical ControversyFrom EverandEvidence of Harm: Mercury in Vaccines and the Autism Epidemic: A Medical ControversyRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (13)

- Grandmoo Goes To Rehab SmallDocument44 pagesGrandmoo Goes To Rehab SmallbvromanNo ratings yet

- PP279 Cohen1Document7 pagesPP279 Cohen1bvromanNo ratings yet

- The Boratization Revisited: Thinking The "South" in European Cultural Studies by Aljoša PužarDocument22 pagesThe Boratization Revisited: Thinking The "South" in European Cultural Studies by Aljoša PužarbvromanNo ratings yet

- Worry in Children Is Related To Perceived Parental Rearing and Attachment by Peter Muris Et Al. (2000) - An ArticleDocument11 pagesWorry in Children Is Related To Perceived Parental Rearing and Attachment by Peter Muris Et Al. (2000) - An ArticlebvromanNo ratings yet

- Current Literature in ADHD by Sam Goldstein (2006) - An ArticleDocument7 pagesCurrent Literature in ADHD by Sam Goldstein (2006) - An ArticlebvromanNo ratings yet

- ETHICON Encyclopedia of Knots (Noduri Chirurgicale PDFDocument49 pagesETHICON Encyclopedia of Knots (Noduri Chirurgicale PDFoctav88No ratings yet

- The Development of Attachment in Separated and Divorced FamiliesDocument33 pagesThe Development of Attachment in Separated and Divorced FamiliesInigo BorromeoNo ratings yet

- Baxshin LABORATORY: Diagnostic Test and AnalysisDocument1 pageBaxshin LABORATORY: Diagnostic Test and AnalysisJabary HassanNo ratings yet

- Learning Activity Sheet MAPEH 10 (P.E.) : First Quarter/Week 1Document4 pagesLearning Activity Sheet MAPEH 10 (P.E.) : First Quarter/Week 1Catherine DubalNo ratings yet

- BlahDocument8 pagesBlahkwood84100% (1)

- Rrs PresentationDocument69 pagesRrs PresentationPriyamvada Biju100% (1)

- Meditran SX Sae 15w 40 API CH 4Document1 pageMeditran SX Sae 15w 40 API CH 4Aam HudsonNo ratings yet

- Tinongcop ES-Teachers-Output - Day 1Document3 pagesTinongcop ES-Teachers-Output - Day 1cherybe santiagoNo ratings yet

- AUDCISE Unit 1 WorksheetsDocument2 pagesAUDCISE Unit 1 WorksheetsMarjet Cis QuintanaNo ratings yet

- CASE 721F TIER 4 WHEEL LOADER Operator's Manual PDFDocument17 pagesCASE 721F TIER 4 WHEEL LOADER Operator's Manual PDFfjskedmmsme0% (4)

- Pamet and PasmethDocument4 pagesPamet and PasmethBash De Guzman50% (2)

- Photosynthesis PastPaper QuestionsDocument24 pagesPhotosynthesis PastPaper QuestionsEva SugarNo ratings yet

- 1Manuscript-BSN-3y2-1A-CEDILLO-222 11111Document32 pages1Manuscript-BSN-3y2-1A-CEDILLO-222 11111SHARMAINE ANNE POLICIOSNo ratings yet

- Company Catalogue 1214332018Document40 pagesCompany Catalogue 1214332018Carlos FrancoNo ratings yet

- 1.8 SAK Conservations of Biodiversity EX-SITU in SITUDocument7 pages1.8 SAK Conservations of Biodiversity EX-SITU in SITUSandipNo ratings yet

- Topic 7: Respiration, Muscles and The Internal Environment Chapter 7B: Muscles, Movement and The HeartDocument4 pagesTopic 7: Respiration, Muscles and The Internal Environment Chapter 7B: Muscles, Movement and The HeartsalmaNo ratings yet

- Sithpat006ccc019 A - 2021.1Document34 pagesSithpat006ccc019 A - 2021.1Mark Andrew Clarete100% (2)

- Method Statement For Lifting WorksDocument12 pagesMethod Statement For Lifting WorksRachel Flores85% (26)

- Uppercut MagazineDocument12 pagesUppercut MagazineChris Finn100% (1)

- Dif Stan 3-11-3Document31 pagesDif Stan 3-11-3Tariq RamzanNo ratings yet

- ReferensiDocument4 pagesReferensiyusri polimengoNo ratings yet

- EESC 111 Worksheets Module 5Document5 pagesEESC 111 Worksheets Module 5Keira O'HowNo ratings yet

- Airport - WikipediaDocument109 pagesAirport - WikipediaAadarsh LamaNo ratings yet

- Ethics, Privacy, and Security: Lesson 14Document16 pagesEthics, Privacy, and Security: Lesson 14Jennifer Ledesma-Pido100% (1)

- Demolition/Removal Permit Application Form: Planning, Property and Development DepartmentDocument3 pagesDemolition/Removal Permit Application Form: Planning, Property and Development DepartmentAl7amdlellahNo ratings yet

- Cuts of BeefDocument4 pagesCuts of BeefChristopher EnriquezNo ratings yet

- Jebao DCP Pump User ManualDocument3 pagesJebao DCP Pump User ManualSubrata Das100% (1)

- Immobilization of E. Coli Expressing Bacillus Pumilus CynD in Three Organic Polymer MatricesDocument23 pagesImmobilization of E. Coli Expressing Bacillus Pumilus CynD in Three Organic Polymer MatricesLUIS CARLOS ROMERO ZAPATANo ratings yet

- Microbes in Human Welfare PDFDocument2 pagesMicrobes in Human Welfare PDFshodhan shettyNo ratings yet

- Docu Ifps Users Manual LatestDocument488 pagesDocu Ifps Users Manual LatestLazar IvkovicNo ratings yet

- BRS PDFDocument14 pagesBRS PDFGautam KhanwaniNo ratings yet