Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Racism & Capitalism. Chapter 3: Racism, Revolution and Anti-Racism - Iggy Kim

Uploaded by

Iggy Kim0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

600 views12 pagesLifelong and hereditary enslavement of some 20% of the population began to stand out as a monstrous aberration. Bourgeois revolutionaries like Benjamin Rush and James Otis fiercely opposed slavery and countered the racist charges of black inferiority. Slavery is a direct violation of the law of nature, and makes every dealer in it a tyrant from the director of an African company to the petty chapman in needles and pins.

Original Description:

Copyright

© Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

PDF or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentLifelong and hereditary enslavement of some 20% of the population began to stand out as a monstrous aberration. Bourgeois revolutionaries like Benjamin Rush and James Otis fiercely opposed slavery and countered the racist charges of black inferiority. Slavery is a direct violation of the law of nature, and makes every dealer in it a tyrant from the director of an African company to the petty chapman in needles and pins.

Copyright:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

600 views12 pagesRacism & Capitalism. Chapter 3: Racism, Revolution and Anti-Racism - Iggy Kim

Uploaded by

Iggy KimLifelong and hereditary enslavement of some 20% of the population began to stand out as a monstrous aberration. Bourgeois revolutionaries like Benjamin Rush and James Otis fiercely opposed slavery and countered the racist charges of black inferiority. Slavery is a direct violation of the law of nature, and makes every dealer in it a tyrant from the director of an African company to the petty chapman in needles and pins.

Copyright:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 12

Chapter 3:

Racism, Revolution and Anti-racism

Bourgeois revolution – the challenge begins

At a time when the bourgeoisie was proclaiming “all Men are created equal, that they are

endowed, by their Creator, with certain unalienable Rights”, many white people reconciled the

subjugation of black slaves and colonial peoples by rationalising that somehow they were, by

nature, not fully human. However, on the other side of the ideological struggle, many white

people also sought to extend the universalising principles of bourgeois democracy to the slaves.

In the revolutionary ferment of late 1700s United States, lifelong and hereditary enslavement of

some 20% of the population began to stand out as a monstrous aberration. In response to a slave

revolt in Boston in 1774, Abigail Adams told her husband John Adams, the later US president,

“it always appeared a most iniquitous scheme to me to fight ourselves for what we are daily

robbing and plundering from those who have as good a right to freedom as we have”.1

Prominent bourgeois revolutionaries like Benjamin Rush and James Otis fiercely opposed

slavery and countered the racist charges of black inferiority. Otis wrote in his Rights of the

British Colonies Asserted and Proved (1764):

The Colonists are by the law of nature free born, as indeed all men are, white or black…. Does it follow that

tis right to enslave a man because he is black? Will short curl’d hair like wool, instead of christian hair, as tis

called by those, whose hearts are as hard as the nether millstone, help the argument? Can any logical

influence in favour of slavery be drawn from a flat nose, a long or a short face? Nothing better can be said in

favour of a trade, that is the most shocking violation of the law of nature, has a direct tendency to diminish

the idea of the inestimable value of liberty, and makes every dealer in it a tyrant from the director of an

African company to the petty chapman in needles and pins on the unhappy coast. It is a clear truth, those who

every day barter away other men’s liberty will soon care little for their own.2

The Reverend Isaac Skillman even asserted in 1772 that the right of slaves to rebel conformed

“to the laws of nature”.3 Benjamin Rush wrote in the following year:

…I need hardly say any thing in favour of the intellects of the Negroes, or of their capacities for virtue and

happiness, although these have been supposed by some to be inferior to those of the inhabitants of Europe.

The accounts which travellers give us of their ingenuity, humanity, and strong attachment to their parents,

relations, friends and country, show us that they are equal to the Europeans…. All the vices which are

charged upon the Negroes in the southern colonies, and the West Indies, such as Idleness, Treachery, Theft,

and the like, are the genuine offspring of slavery, and serve as an argument to prove that they were not

intended by Providence for it…

Future ages, therefore, when they read the accounts of the slave trade (if they do not regard them as fabulous)

will be at a loss which to condemn most, our folly or our guilt, in abetting this direct violation of the laws of

Nature and Religion.4

It was in the birthplace of racial oppression that some of the most ardent and radical critics

of slavery first emerged under the driving force of revolution. In order to wage their

revolutionary struggle, the American bourgeoisie had to rally the mass of (white) plebeians

under the banner of universal natural rights and liberties. The seething, uncontrollable ferment

and upheaval that was then unleashed naturally threatened to reach into the ranks of the black

1

Herbert Aptheker, A History of the American People: The American Revolution 1763-1783, International

Publishers, New York, 1960, p. 209

2

Louis Ruchames (ed.), Racial Thought in America Volume 1: From the Puritans to Abraham Lincoln, Grosset &

Dunlap, New York, 1969, p. 138

3

Aptheker, op. cit.

4

Ruchames, ibid., pp. 140-41

Ch. 3: Racism, Revolution and Anti-racism, by Iggy Kim 1

toilers themselves. In any revolution, cracks can spread throughout the edifice of the ruling

order. Indeed, large numbers of African-Americans did take part in the upsurge. At least 5000

were regular soldiers in the revolutionary army, 5 many distinguishing themselves in combat like

the famous Salem Poor. Some were freed and even awarded land and pensions. Still many

others participated in a civilian capacity. The whole process even radicalised some slaveholder

revolutionaries. John Laurens, a South Carolinian lieutenant-colonel and son of a slaveholder,

was an early advocate of freeing and arming 3000 slaves in exchange for military service. He

won support from Congress in 1779 but was vetoed by the South Carolina assembly. Laurens’

father had written to him four years earlier to tell him that he was freeing his slaves and “cutting

off the entail of slavery”.6

Ultimately though, the American revolution was limited to the political sphere. Unlike the

more far-reaching social revolution in France a few years later, the Americans were out to

secure political independence from London, another bourgeois state, without touching the

existing social-economic system. As such, the revolutionary alliance of class forces was

founded on the interests and structures of US capitalism at that time – not only the mass of petty

bourgeois artisans, farmers, and the mercantile (and some manufacturing) bourgeoisie in the

north, but also the profitable slave-worked plantation empire in the south. Northern capitalists

and southern slaveholders had distinct interests, but these had not yet become antagonistic. The

original US constitution of 1777 had confederated the thirteen colonies into a union of

sovereign states and protected the southern slave system from outside interference. In the

immediate years after the revolution’s victory in 1783, central government was kept to a

minimum, lacking even a national army. When a Constitutional Convention came together in

1787 to devise a new federal system, everyone was well aware of the delicacy of negotiating a

national government that would preserve harmony between north and south. The convention

eventually came up with a state structure that would allow the two wings of the ruling class to

work together while protecting their separate interests. Congress was split into two houses, with

only the lower house subject to direct election. Both the Senate and president were to be

indirectly elected. There were also property qualifications placed on voters. This was all

codified in a new Constitution that embarrassedly avoided the words “slave” and “slavery” and,

instead, used the euphemism of “other persons”. The Constitution counted each slave as “three-

fifths” of a person so that the number of southern representatives in Congress matched those

from the North with its greater number of white men.

The compromise of 1787 gave the southern slavocracy a confidence boost. They had, for

now, brought partly under their control what was potentially the biggest threat to their power

and legitimacy – a new revolutionary government resting on the allegiance of a mass of non-

slaveholding free citizens. In fact, the slavocracy deliberately worked to foster a political

alliance with the small farmers – the majority of the population – not in support of slavery, but

around trade, tax and monetary policies that favoured their shared agricultural interests. Leading

slaveholder politicians of this time, such as Thomas Jefferson, who won the presidency in 1800,

continue to be eulogised today as a champion of the “little people”.

The free, white plebeian citizenry were generally hostile to slavery. In the North, where the

weight of small freehold farmers and artisans was much greater, new settlements banned

slavery. But this hostility to the institution of slavery was not necessarily matched by a sense of

solidarity with the slaves (or former slaves). Foreshadowing later racism elsewhere against

“servile” immigrants of colour, many free white towns in the Midwest excluded blacks, free or

slave. Even anti-slavery revolutionaries like Tom Paine had reservations about extending full

and equal citizenship to African-Americans. Blacks were seen as alien to the organic bonds of

free smallholding community which the revolution rested on. Even those who went as far as

advocating full emancipation saw a solution in resettling blacks outside the United States. The

new plebeian democracy was undoubtedly tainted by a racially exclusionist streak.

To foster their alliance with the farmers, slaveholder politicians settled for some restrictions

on the expansion of slavery while fiercely defending its preservation in the southern states. The

importation of slaves was outlawed in 1808, although the law was hardly enforced. Some

northern states abolished the slave trade but not slavery itself. Some states decreed freedom for

future generations born to slaves, but only after they had served out a period of servitude into

their adult years, ostensibly to repay their masters for their keep.

5

Aptheker op. cit., p. 226

6

Ruchames, op. cit., p. 157

Ch. 3: Racism, Revolution and Anti-racism, by Iggy Kim 2

Two subsequent developments in 1793, one at home, the other abroad, were to

simultaneously crank up the slave economy and eventually produce the conditions of its

destruction. At home, in that year, the invention of the cotton gin allowed the mass production

of that commodity so vital to the emerging Industrial Revolution. Cotton exports soared, from

500,000 pounds in 1793 to 18 million pounds in 1800 and 83 million by 1815. In 1801-5 40%

of British cotton imports came from the US.7 Cotton became the US’s most important crop and

came to overshadow all others in the plantation economy. The southern slave zone became the

driving engine of the US economy. However, in a dialectical twist, this very prosperity was to

eventually upset the delicate alignment of class forces that had produced the 1787 compromise

and allowed the slavocracy to survive.

The anti-racist Haitian Revolution

Also in 1793, the French Revolution entered its radical Jacobin phase. With moves toward a

constitutional monarchy in shambles and a mass movement of poor sans-culottes mobilised, a

section of the revolutionary bourgeoisie was to lead the most far-reaching social and political

revolution to date. In the Jacobin phase, the revolution spread to France’s slave colony in St

Domingue (present-day Haiti) and racial oppression was dealt its first major blow. In the words

of the West Indian Marxist, C.L.R James, in his classic work, The Black Jacobins:

Paris between March 1793 and July 1794 was one of the supreme epochs of political history. Never until

1917 were masses ever to have such powerful influence – for it was no more than influence – upon any

government. In these few months of their nearest approach to power they did not forget the blacks. They felt

towards them as brothers, and the old slave-owners, whom they knew to be supporters of the counter-

revolution, they hated as if Frenchmen themselves had suffered under the whip.

It was not Paris alone but all revolutionary France. “Servants, peasants, workers, the labourers by the day in

the fields” all over France were filled with a virulent hatred against the “aristocracy of the skin.” There were

many so moved by the sufferings of the slaves that they had long ceased to drink coffee, thinking of it as

drenched with the blood and sweat of men turned into brutes.8

A complex hierarchy of racial castes had governed St Domingue, the jewel of the French

colonies. The white colonial-settlers were vastly outnumbered by the slaves. As such, unlike

mainland North America, people with both black and white parentage, the “mulattoes”, were

freed and coopted into functioning as an intermediate social buffer on behalf of the white

slaveholders, who were an even smaller minority among the general white population. People of

mixed colour formed the backbone of the maréchausée, a police force for capturing fugitive

slaves. Throughout the slave-worked Americas, a growing population of mixed ancestry was

produced by the male slaveholder’s treatment of slave women as sexual chattel. However, in the

French Caribbean, just to be sure to know on which side they ultimately stood, 128 formal

categories recognised the huge permutations of intermixture while clearly dictating that they all

belonged to the status of “mulatto”. Thus, even the whitest of the mixed coloureds, the sang-

mêlé with 127 parts white ancestry and one part black, was still a person of colour.9 They

suffered all sorts of discrimination and legally occupied a subordinate position.

Nevertheless, people of mixed ancestry were incorporated into the free population and could

thereby climb the social ladder to a certain extent. Many even became slaveholding planters.

From the outset then, the racial caste system in St Domingue was inherently less stable than in

the US. When the revolution came, the wholesale discrediting of privilege by birth began to

further shake up the racist assumptions of this caste system. The choice of criterion for political

representation was ultimately posed between racial or property privilege, one having been

acquired by birth, the other including those many bourgeois who had acquired it by social

mobility. The planters wanted narrow political representation to protect their economic interests

against the diktats of Paris; the free, propertied people of colour wanted political and legal

equality with the rest of their class; the petits blancs (“small whites”) wanted liberty, equality

and fraternity for all white men and resented any prospect of propertied people of colour getting

representation at their expense. The slaves as yet were beyond any consideration.

Therefore, the radical democracy of the white plebeians in St Domingue was initially

synonymous with preserving the racial caste system. Once again, fulfilling their role of social

buffer, many people of mixed colour were drawn into an alliance with the counter-revolutionary

7

Robin Blackburn, Overthrow of Colonial Slavery, Verso, London, 1988, p. 276

8

C.L.R James, The Black Jacobins: Toussaint L’Ouverture and the San Domingo Revolution, Random House, New

York, 1963, pp. 138-39. In this passage James relies on a revealing primary source – a book published in 1802,

written by a French colonist who opposed emancipation.

9

ibid., p. 38

Ch. 3: Racism, Revolution and Anti-racism, by Iggy Kim 3

forces of the colonial administration, against the white plebeian masses. Governor De Peynier

instructed the commandants of the districts, “It has become more necessary than ever not to give

[people of mixed colour] any cause for offence, to encourage them and to treat them as friends

and whites.”10

In France itself, the colonial question came to occupy a key position in the shifting tides of

the revolution. An abolitionist group had emerged during the growth of the political movement

of the French bourgeoisie, the Friends of the Blacks. Many of the early leaders of 1789 were

also key figures in this group. They were ideologues who universalised the principles of 1789 to

also include blacks. Their views were best summed up by the fiery interjection of Mirabeau

against d’Arsy, the planter delegate to the famous tennis-court meeting of the Third Estate in

1789:

You claim representation proportionate to the number of the inhabitants. The free blacks are proprietors and

tax-payers, and yet they have not been allowed to vote. And as for the slaves, either they are men or they are

not; if the colonists consider them to be men, let them free them and make them electors and eligible for

seats; if the contrary is the case, have we, in apportioning deputies according to the population of France,

taken into consideration the number of our horses and our mules?11

But there were also many bourgeois in the revolutionary parliament whose fortunes were tied

to colonial slavery. They were sensitive to any move that upset the racial hierarchy which, in

turn, would undermine slavery. Most crucially, the planters wielded the threat of secession.

Initially, Paris decided it did not want to lose the colonies and compromised.

The trans-Atlantic French revolution was played out by a dizzying mix of rival social and

political forces: rich whites, poor whites, rich people of colour, colonial planters, metropolitan

bourgeoisie, constitutional monarchists, absolute monarchists, radical republicans, those in

favour of the mulatto vote, those against. In amongst this, first the people of mixed colour, then

the slaves themselves, came to play the decisive role. The whites as a whole were outnumbered

in St Domingue. As such, whites on all sides were soon forced to recognise that the mixed

coloureds held the balance of power. In May 1791 Paris gave the vote to those coloured people

whose parents were both free. But this was rescinded in September, when the revolution had

temporarily swung to the right.

The cracks were nonetheless glaring and emboldened the racially oppressed. The wealthy

coloureds began organising independently. Masses of slaves also took up arms and revolted.

They were wooed for a time by the Spanish in the eastern half of the island (present-day

Dominican Republic), who commissioned them into their army. The mulattoes then allied with

the white property-owners to put down this slave uprising. But the whole structure of slavery

required the maintenance of racial castes. People of mixed colour, having gained a taste for

independent organisation, lost confidence in this alliance. Further, with ongoing moves by Paris

to recognise their legal equality, the mixed coloureds began to close ranks with the revolution.

Royal intrigues in the metropolis were driving a widening polarisation. The Jacobins were going

from strength to strength. They effectively took the reins of government in early 1792. On April

4 they passed a decree giving full civil rights to all free adult males, regardless of colour. In late

1792 the polarisation gave way to a second revolution as the king went over to open counter-

revolution. The constitutional monarchy was ditched and a republic formed.

At about the same time, Paris dispatched three commissioners to restore order in St

Domingue. These officials were led by a Jacobin who built an alliance with the commanders of

the mulatto forces and set up a Légion d’Egalité, to put down both the slave armies and the

counter-revolution. Many of the wealthy whites had now openly gone over to the royalists. The

royalists called on the assistance of foreign powers who were very nervous about the spread of

the French example. German and British troops invaded France; British and Spanish troops

entered St Domingue. Under such grave threat, the mass of the revolutionary forces in France

radicalised even further. The danger of the sans-culottes in the metropolis, and that of the slaves

in the colonies, was now far outweighed by the royalist counter-revolution. The revolutionary

bourgeoisie moved sharply to the left. The vacillating Girondins were purged and the Jacobins

consolidated their power in June 1793, whereupon they mobilised a popular defence of the

revolution.

It was in this knife-edge situation that a dramatic shift in the balance of forces took place in

St Domingue. Under siege, the republican commissioners were finally forced to decree

emancipation and seek the alliance of the armed slaves who, in turn, began to see their own

10

ibid., p. 63

11

quoted in ibid., p. 60

Ch. 3: Racism, Revolution and Anti-racism, by Iggy Kim 4

interests in the radicalising French Revolution. The petits blancs split: those more ardently

concerned about preserving the gains of the revolution accepted the alliance with the blacks;

others went over to the royalists.

In January-February 1794 this movement was capped by an extraordinary episode in the

National Convention in Paris. It’s an episode that still stands with momentous stature in the

whole history of revolutionary movements. A trio of deputies from St Domingue was sent to

request an official decree of emancipation from the metropolis: Bellay, a freed slave; Mills, a

person of mixed colour; and Dufay, a white man. A French deputy introduced them with the

following words: “Since 1789 the aristocracy of birth and the aristocracy of religion have been

destroyed; but the aristocracy of the skin still remains. That too is now at its last gasp, and

equality has been consecrated. A black man, a yellow man, are about to join this Convention in

the name of the free citizens of St Domingue.”12

After an eloquent and passionate speech by Bellay, requesting the Convention abolish

slavery, a French deputy moved the motion: “When drawing up the constitution of the French

people we paid no attention to the unhappy Negroes. Posterity will bear us a great reproach for

that. Let us repair the wrong – let us proclaim the liberty of the Negroes. Mr President, do not

suffer the Convention to dishonour itself by a discussion.” The chamber burst into sustained

acclamation. Embraces and kisses followed, met by further applause. A coloured woman sitting

in the public gallery, tears streaming down her face, was invited to sit to the left of the

President. Lacroix, who had earlier introduced the St Domingue deputies to the Convention,

then proposed the wording of the decree: “The National Convention declares slavery abolished

in all the colonies. In consequence it declares that all men, without distinction of colour,

domiciled in the colonies, are French citizens, and enjoy all the rights assured under the

Constitution.”13 The Commune of Paris held a celebration at the Notre Dame, which the

revolutionaries now called the Temple of Reason.

But it did not stop at mere decrees. The Jacobins dispatched a naval fleet to the Caribbean to

wage a revolutionary war for the liberation of all slaves. This fleet of 1200 soldiers arrived with

a guillotine and a printing press. It ran off the emancipation decree, the Declaration of the

Rights of Man and Citizen, and other revolutionary documents, in Spanish, Portuguese, Dutch

and English, as well as French, to distribute all over the Caribbean.14

With emancipation now signed, sealed and delivered by Paris, the most proficient of the

slave armies, that led by Toussaint Louverture, came over to the revolution. Thereupon the

revolutionary army of Black Jacobins dealt a series of terrific blows to the counter-revolution

and, simultaneously, waged a war of revolutionary emancipation of those still enchained on the

plantations. However, after defeating the Spanish and British, the forces of Louverture had to

face France itself. With the fall of the Jacobins and the Thermidor backlash, Napoleon’s army

simultaneously spread the revolution in Europe and tried to reimpose slavery in St Domingue.

But the Black Jacobins prevailed again. Twelve years before Napoleon’s defeat at Waterloo,

this black army of former slaves drove out the French and established the Republic of Haiti in

1804 – the first black bourgeois government in the world and the second revolution in the

Americas, but the first to give civil rights to all its people, and one, no less, led by former

slaves. The Haitian Revolution sent tremors throughout the Americas and Europe, inspiring

rebellion among slaves and fear among slaveholders.

Thus, in the one and the same year, an economic turning point that dramatically upped the

demand for slave labour in the US was matched by a spectacularly successful movement of

revolutionary emancipation in the Caribbean. They were the contradictory outcomes of the two

great bourgeois revolutions: the first had ended in a sordid compromise with the slavocracy and

the second in the self-emancipation of the slaves. This twin, dialectically connected process

revealed a more general truth. Just as capitalism and racism had been joined in birth, the fates of

revolution and anti-racism were one and the same. The more complete bourgeois revolutions (in

France, Haiti, and the nineteenth-century Bolivarian revolutions in continental Latin America)

were associated with the emancipation of slaves; the retreat of revolution (in the US and Britain,

and later in France under Napoleon) was associated with renewed racial oppression and the

deepening of racist ideology.

Nineteenth-century ‘scientific’ racism

12

quoted in ibid., pp. 139-40

13

ibid., pp. 140-41

14

Blackburn, op. cit., p. 226

Ch. 3: Racism, Revolution and Anti-racism, by Iggy Kim 5

In Britain and the US, a whole trend of chauvinist literature against the French Revolution

formed an important adjunct to the deepening racist world-view of the nineteenth century. The

inherent extremism of the French “race” was counterposed to the more balanced temperament

of the Germanic/Teutonic Anglo-Saxons. This chauvinism was also ultimately directed at the

simmering radical-revolutionary impulses in Britain and the United States. It sought to

legitimise the 1787 compromise with the slavocracy and Britain’s much earlier compromise

with the monarchy.

In Britain, this chauvinism was also needed to justify the colonial oppression of the Irish, in

a period when Irish nationalism was becoming a political force that looked to the French

Revolution for inspiration. Indeed, for the purpose of chauvinist attack, the French and Irish

were often lumped together into the single category of “Celt”. This literature was best summed

up by one of the US’s foremost historians in the nineteenth century, Francis Parkman:

The Germanic race, and especially the Anglo-Saxon branch of it, is peculiarly masculine and, therefore,

peculiarly fitted for self-government. It submits its action habitually to the guidance of reason, and has the

judicial faculty of seeing both sides of a question…. the French Celt is cast in a different mould. He sees the

end distinctly, and reasons about it with an admirable clearness; but his own impulses and passions

continually turn him away from it. Opposition excites him; he is impatient of delay, is impelled always to

extremes, and does not readily sacrifice a present inclination to an ultimate good. He delights in abstractions

and generalizations, cuts loose from unpleasing facts, and roams through an ocean of desires and theories.15

Dr Robert Knox, an anatomy professor at the Edinburgh College of Surgeons, wrote in 1850

that the Celts are characterised by “furious fanaticism: a love of war and disorder; a hatred for

order and patient industry; no accumulative habits; restless, treacherous, uncertain; look at

Ireland.” Further, “The source of all evil lies in the race, the Celtic race of Ireland.”16

This sort of chauvinism was not racist per se, that is, it could not be based on any

identifiable physical markers, such as dark skin. However, it nonetheless sought to portray

French and Irish ethno-cultural traits as inborn and thereby served racism by reinforcing a

biological conception of people’s social and cultural characteristics. Subsequently, racism and

national-ethnic chauvinism were tightly interwoven, reaching its pinnacle in the Nazi ideology

of Teutonic superiority over other white people (especially the Slavs and Jews, whom they

sought to portray as non-white), as well as African and Asian peoples (with the pragmatic

exception of the Japanese, whom they needed a military alliance with and thus labelled

“honorary Aryan”).

At the same time, the French Revolution itself was partly rolled back under Napoleon. The

French bourgeoisie sought to find a new equilibrium after the “excesses” of the Jacobin period.

The spectre of 1848 then drove the last nails into the coffin of any remaining bourgeois

revolutionary momentum. The French tried to expunge the memory of 1793-4: they temporarily

restored slavery in the Caribbean colonies in 1802 (trying but failing to retake Haiti) and

embarked on a new colonial offensive. Racist ideology returned with a vengeance.

The retreat of the nineteenth-century bourgeoisie was aided by the onward march of science.

Instead of debunking racist assumptions, science actually did the opposite in the hands of the

“learned men” of the British Century – a century built on the debris of 1848; a century of

controlled, gradualist advances in the Westminster political system, and a vast expansion of

colonial fortunes. The world-view of the nineteenth-century scientist was unshakeably

embedded in a racial hierarchy, and rather than explode it, the tools of science were harnessed

to secure this ideological bedrock. Even the great, enlightening discoveries of Charles Darwin

were pressed into the service of validating racist ideology.

For the anatomist Robert Knox, “Race is everything. Literature, science, art, in a word,

civilisation, depend on it.”17 The renowned man of letters, Ralph Waldo Emerson, wrote in

English Traits (1856), “It is race, is it not? that puts the hundred millions of India under the

dominion of a remote island in the north of Europe…. Celts love unity of power, and Saxons the

representative principle.”18 French scientist, Julien-Joseph Virey, wrote in his Dictionary of

Medical Science (1819), “Among us [whites] the forehead is pushed forward, the mouth is

pulled back as if we were destined to think rather than eat; the Negro has a shortened forehead

and a mouth that is pushed forward as if he were made to eat instead of to think.”19

15

quoted in Thomas F. Gossett, Race: The History of an Idea in America, Southern Methodist University Press,

Dallas, 1963, p. 95

16

quoted in ibid., p. 96, italics in the original

17

ibid., p. 95

18

ibid., p. 97

19

quoted in the website 19th Century Racism, http://www.geocities.com/ru00ru00/racismhistory/19thcent.html

Ch. 3: Racism, Revolution and Anti-racism, by Iggy Kim 6

Thus, well before the imperialist epoch, many bourgeois intellectuals in the field of social

and political theory abandoned the ideals of the Enlightenment and came to serve an

increasingly bankrupt capitalist system. Marx and Engels alone continued to uphold the banner

of consistent humanism and eventually built up a powerful ideological and political counter-

pole for the succession of capitalism by an even more enlightened and scientific social system.

The fates of revolution and racism were one and the same. The more complete bourgeois

revolutions (in France, Haiti, and the nineteenth century Bolivarian revolutions in continental

Latin America) were associated with the abolition of slavery; the retreat of revolution (in the US

and Britain, and later in France) was associated with renewed racial oppression and the

deepening of racist ideology.

The Second American Revolution

Nevertheless, despite any retreat the seeds of mass politics and democratic revolt had been

safely sown. No revolution can ever be fully undone. The petty bourgeoisie, sold out by the

compromises of the big bourgeois, continued to agitate and organise for more far-reaching

change, pulling in its wake the emerging proletariat. In the US, Britain and Europe, the

aspirations of this democratic citizenry included the push for the abolition of slavery. The 1848

revolutions on the European continent had been crushed in their homelands but still resulted in

the final death blow to slavery in the French Caribbean, where it had been restored by Napoleon

in 1802. In the US, this simmering anti-racist impulse developed the furthest – into a second

revolution. The “French disease” was to infect the heartland of racial slavery.

The Second American Revolution was a bourgeois revolution that ran from 1861 to 1877. It

was made up of two components, the American Civil War in 1861-65 and the period of Radical

Reconstruction following the war. This revolution pitted the North’s industrial bourgeoisie and

its allies, chiefly the mass of small farmers and then the freed and fugitive slave armies, against

the southern slavocracy which formed the breakaway Confederate States of America. What

began as a war to restore the unity of the United States eventually unleashed a titanic,

revolutionary movement of black self-emancipation that both mirrored and took to completion

what was begun by the first detachments of black revolutionary soldiers in 1775-83.

The invention of the cotton gin in 1793 had thrust cotton to the centre of the US economy.

US capitalism united behind this tremendous, slave-produced boom. The small farmers

produced food for the plantations, the northern merchants profited from selling and exporting

the cotton. But towards the mid-1800s the slave system began to outlive its usefulness. By then

it had fulfilled its kick-start function and could be dispensed with, as much of the advanced

capitalist world, including parts of the US, began to move on to the phase of general

industrialisation. The profits accumulated from the cotton boom, together with soaring

immigration and the introduction of steam power and the railroad, opened the way for a rapid

growth of manufacturing in the North.

While the slavocracy had adapted slave labour for the capitalist mode of production, it still

retained its core, pre-capitalist weakness – slavery severely hindered technological innovation

and blocked the development of a domestic mass market. If the key tools you own, slaves, are

also creative producers of surplus value; if the slaves can be forced to carry out almost every

task on the plantation – then there is no objective drive to technologically innovate and

diversify. And if there is no such innovation, then there is no corresponding development and

diversification in the types of industries. The Cotton Kingdom is forever condemned to remain a

backward agrarian economy servicing an outside textile industry, exclusively dependent on

cheap labour and a growing supply of land. Moreover, without a mass of wage-earners, there is

no growth in a domestic mass market, further hindering capitalist development. While the

slavocracy may have wallowed in their lavish, aristocratic pretences, they became more and

more of a fundamental block on the overall, strategic interests of the US capitalist class and

economy. This was most acutely felt by the newly emerging industrial bourgeoisie in the North.

By the mid-1800s US capitalism reached a fateful fork in the road. Would the United States

be dominated by a slave-dependent, agrarian ruling class, or would it achieve the industrial and

financial dynamism that would eventually lead it towards global domination in the twentieth

century? Would US agriculture serve British or American capitalism? Would the new territories

opening up in the western United States serve the needs of industrial development, or would

they succumb to the slave-worked plantation empire? At this fork in the road, the 1787

compromise broke down and the separate interests of the two wings of the US ruling class went

over into open, revolutionary conflict.

Ch. 3: Racism, Revolution and Anti-racism, by Iggy Kim 7

In addition to the rise of the northern industrial bourgeoisie, there were other changes in the

alignment of class forces towards the mid-1800s. Principally, the alliance between the small

farmers and the slavocracy collapsed. They came into conflict over land. The invention of the

cotton gin allowed cotton to be grown and processed far inland. The slavocracy became land-

hungry and their “Cotton Kingdom” began pushing westwards. They were no longer on the

defensive; they no longer felt they had to compromise by allowing slave-free states in return for

maintaining the “southern way of life”.

On the other hand, there was a tremendous growth in European immigration, especially

following the Irish potato famine and the defeat of the 1848 revolutions. To this day, the

greatest influx of immigrants, as a proportion of the existing US population, arrived in the years

1845-50. This massively expanded the ranks of the American yeomanry, spreading to the

Midwest and beyond in search of political and agrarian freedom. Today, the legend of the

westward pioneer continues to be the stuff of novels, movies, musicals and TV shows. The

Midwest farmer soon moved to the centre of the US agricultural economy. The 1850 census

revealed that the northern hay crop alone equalled the combined market value of all southern

staples – cotton, tobacco, rice, hemp and sugar.20 Further, the mass of small farmers came to be

less dependent on southern markets – the rapidly growing industrial towns of the North were

now taking more and more of the farmers’ foodstuffs.

With the growth of the American yeomanry, the battle was resumed for the meaning and

future of American democracy. New aspirations were awoken and accounts had to be settled

with the sordid compromises of the first revolution. This, as always, was grounded in concrete,

material interests. A series of political contests over the expanding western territories, each

fiercer than the last, unfolded between the slavocracy, on the one hand, and the democratic

petty-bourgeoisie and northern industrial capitalists, on the other: Missouri in 1819-20, Texas in

1836-45, California in 1849-50, Kansas in 1854-61. Each new application for statehood teetered

the balance of equal Congressional seats for slave and free states, contained in the 1787

constitutional compromise. The fight over each territory amounted to whether they would be

admitted into the Union as a free or slave state. A compromise in each case only prolonged the

inevitable, open rupture: Missouri was to be admitted as a slave state; all others to the north

would be free. California was to be free, in exchange for the notorious Fugitive Slave Act of

1850 which made it mandatory for a fugitive slave anywhere, North or South, to be forcibly

returned to their owner. The Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854 overturned the Missouri

Compromise and left the decision to the people of the territory.

This increasingly bitter struggle dominated United States history in the first half of the

nineteenth century and, in the second half, finally forced back onto the historical agenda a

settlement of the slave question once and for all. A range of social and political forces helped

shape the revolutionary and anti-racist character of this unfolding process. Among white

democrats and free blacks in the North, there arose for the first time a mass movement explicitly

and singularly focused on abolishing slavery and emancipating the slaves. This movement allied

with counterparts in Europe. It was aware of, and sensed a kinship with, the revolutionary

movements of 1848. Indeed, some abolitionists correctly saw their mission as an integral part of

the broader, international democratic struggle and felt a renewed sense of responsibility in the

wake of the 1848 defeats. This movement embraced both black and white activists. It helped

give birth to the first movement for women’s rights in the United States. The abolitionists

pioneered a wave of lively, influential activist newspapers, consciously setting out to agitate and

propagandise for the anti-slavery movement. The fight even reached the level of an armed,

guerrilla struggle.

It was the conscious, deliberate intervention of the anti-slavery movement into the changed

class alignments of the early to mid-1800s that gave a conscious focus and program to the white

plebeians’ struggle with the slavocracy. They used a range of devices to build the movement.

The newspaper of the American Anti-slavery Society, The Liberator, played a crucial part,

helping to draw into the movement such important leaders as the ex-slave Frederick Douglass.

Douglass later started his own newspaper, the North Star, specifically to encourage the self-

organisation of African-American activists. A hectic schedule of lecture tours and rallies kept

up the intense agitation and propaganda. The AAS and other organisations produced a large

range of widely-circulated pamphlets and books.

20

Peter Camejo, Racism, Revolution, Reaction, 1861-1877: The Rise and Fall of Radical Reconstruction, Monad

Press, New York City, 1976, p. 23

Ch. 3: Racism, Revolution and Anti-racism, by Iggy Kim 8

The abolitionist movement arguably took off in the political climate triggered by two events:

the publication of a pamphlet by a free black man in Boston in 1829 and the slave revolt led by

Nat Turner in Virginia in 1831. David Walker’s Appeal to the Colored Citizens of the World

could be said to be the first articulation of Black Power, asserting the legitimacy of black

people’s rage, advocating the right of black people to self-defence, calling for open rebellion

against racism by slaves and free blacks alike, and insisting on the inevitable end of white

domination. Walker and many other radicalising blacks at the time were influenced by the

revolution in Haiti – a thunderous event that shook the whole of the Americas and put the fear

of freedom into the slavocracy. Slaveholders censored, sensationalised and demonised news of

what had happened in Haiti. The US government took a hostile position and refused to

recognise the new revolutionary government of the Black Jacobins. The slavocracy saw the

likes of David Walker as a home grown Black Jacobin lurking in their midst. They censored and

confiscated his book, while free blacks smuggled it into the South. The book went through six

editions. Eventually a price was put on Walker’s head and he was found murdered some years

later.

Abolitionists intervened into each fight over the western territories, culminating in the battles

over California and Kansas. The Kansas-Nebraska Act, in giving the settlers the choice of

whether the new state should be free or slave, left the field open for an all-out struggle between

pro- and anti-slavery forces. Settlers from both sides flooded in, one side from the northeast,

and the other from neighbouring Missouri, a slave state. Armed clashes broke out. Both sides

set up rival governments and parliaments, the pro-slavery settlers resorting to outright electoral

fraud. Activists throughout the North raised money, supplies and weapons for the “free-soilers”.

The final compromise over Kansas turned into its very opposite and became the precursor to the

civil war that began the second revolution.

In the struggle over Kansas, that magnificent hero and martyr, John Brown, made his first

major appearance leading successful attacks against pro-slavery terrorists. This Midwestern

farmer was a militant abolitionist who believed that the struggle against slavery could not be

won unless blood was spilt. Unlike some white abolitionists, Brown was not afraid of slaves

taking up arms for their own liberation. In fact, he saw the insurrection of slaves as the only way

to end slavery. John Brown was one of the first truly anti-racist white revolutionaries. As

Frederick Douglass, a black revolutionary and close friend of Brown, said upon first meeting

him, “[T]hough a white gentleman, [Brown] is in sympathy a black man, and as deeply

interested in our cause, as though his own soul had been pierced with the iron of slavery.”21 In

1859 John Brown and two of his sons joined with 19 black and white men to stage a guerrilla

raid on Harpers Ferry, a federal arsenal, in order to capture weapons and distribute them to

slaves throughout the South. The raid was crushed and Brown hanged, but this momentous

event, together with Brown’s testimony at his trial, inspired many abolitionists to new levels. In

turn, it hardened the slavocracy even further and made civil war all the more inevitable. Harpers

Ferry was to the Second American Revolution what the Moncada Barracks was to the Cuban

Revolution nearly 100 years later.

The escalating conflict between “free-soilers” and the slavocracy sharpened national politics.

It gave birth to the anti-slavery Republican Party which was later transformed into the party of

the second revolution. Previously the Whigs had only put up a timid and hesitant fight against

the party of the slavocracy, the Democrats. When the Republican Abraham Lincoln was elected

president in 1860 the slavocracy resorted to secession, even though Lincoln was opportunistic in

his attitude towards slavery. Faced by the intransigence of the breakaway South, he tried to

conciliate with the Confederacy. Even when war broke out, he tried to retain the loyalty of those

slave states that did not secede by promising to maintain slavery if they joined in the fight

against the Confederacy.

It was only as the war became more and more embittered that it transformed into a full-scale

war against slavery. In the process, the Republican Party attracted a current of bourgeois

revolutionaries, including Frederick Douglass, and was pushed sharply to the left. Emancipation

was proclaimed by the Republican administration of Abraham Lincoln and hundreds of

thousands of fleeing slaves were drawn into active participation in a war for their own collective

liberation. Large columns of fully-armed black men, who felt the justice of the struggle in their

bones, were an amazing and inspiring sight to the millions of downtrodden black civilians. On

the other hand, the sight of black men with guns alarmed racist whites. Black units were

21

Quoted in US Public Broadcasting Service, People & Events: John Brown 1800-59,

http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/aia/part4/4p1550.html

Ch. 3: Racism, Revolution and Anti-racism, by Iggy Kim 9

especially repugnant to the white supremacist Confederate forces, who shot black prisoners,

including those who surrendered. Non-combatant African-Americans also played their part, as

part of the crucial civilian support base for the Union army. If ever there was a just war, this was

it, the most destructive war of the nineteenth century which took more American lives than the

first and second world wars combined. No war since has killed that many Americans in a single

conflict.

On the foundations of the massive upheaval of the Civil War, the Republicans led a post-war

process of Radical Reconstruction and carried through a second bourgeois-democratic

revolution. They extended democratic rights to the mass of freed blacks in the South and, by

1867, ensured the election and appointment of a wide layer of African-American politicians,

judges, sheriffs, mayors and other government officials. This dramatic extension of democratic

rights empowered the mass of ex-slaves to self-organise. Radical Reconstruction also

established the first public schools in the South, which allowed not only black children, but also

the children of poor whites, to attend school for the first time ever.

Again, though, all this was limited to a political revolution and remained partial. The mass of

ex-slaves were crying out for land – 40 acres and a mule. But the northern industrial bourgeoisie

and the professional politicians who controlled the Republican Party had relented to Radical

Reconstruction only in order to shore up Republican power in the South. As such, they refused

to countenance land reform and, indeed, bought up a lot of the former plantation lands

themselves. Eventually, a complex combination of a severe labour shortage in the South (now

that slaves were freed), an economic depression in 1873, discontent among poor white farmers

with the economic policies of the northern industrialists, and massive corruption scandals in the

Republican Party, all led to a catastrophic derailing of Radical Reconstruction and the driving

down of the Southern black population into an underclass of poor tenant farmers and super-

exploited rural workers – all under the catch-cry of “stability” and “reconciliation”. In these

circumstances, the Democrats made a comeback, but this time remade as an alternative,

conservative party of the industrial bourgeoisie favouring the smashing of Radical

Reconstruction.

But, by its very nature, the repression of the African-American movement could not be

peaceful. It took waves of horrific terrorist violence by the Ku Klux Klan, the White Leagues

and other white supremacist terror gangs to intimidate black voters and eventually install racist,

Democrat state governments in the South. Fearful of escalating this conflict, Radical Republican

governors treacherously refused to answer the demands of many blacks and rank-and-file white

Radical Republicans to organise and arm popular militias to crush the terrorists. At the same

time, the Republican federal government became increasingly hesitant to intervene with federal

troops. Now that slavery had been abolished, and thereby a key obstacle to further industrial

development removed, and now that the Democrats had been reformed, the northern industrial

bourgeoisie were much more worried about the mass of restless blacks – especially the prospect

of armed ones – than the return of Democrat governments in the South.

With the defeat of Radical Reconstruction, white supremacist governments triumphed in the

South, and race relations, again, became a purely local affair for each state to settle by itself.

One could say that a partial secession had been successful. During the remainder of the

nineteenth century and in the early twentieth century, Southern state governments – as well as

some Northern ones – implemented a stringent system of racial segregation. This highly

oppressive system of social policing ensured that, while African-Americans were not re-

enslaved, they would be legally subordinated on the basis of their skin colour and kept down as

a source of extra-cheap and reserve labour. Earlier, at the height of the revolution, the

Reconstruction Amendments to the US Constitution had explicitly enshrined the abolition of

slavery and an end to racial discrimination. However, in what became the definitive legal seal

on the shunting of the second revolution, the US Supreme Court manoeuvred around these

constitutional amendments in the infamous 1896 Plessy vs. Ferguson ruling that segregation

was not unconstitutional because blacks and whites were “separate but equal”.

It was an astonishing example of the process of Thermidor, first seen following the French

Revolution. While the explosive tumult of revolution can not be completely undone, a faction or

section of the revolutionary forces may control and partially roll it back within the very

framework of the revolution itself to suit their narrow, sectional interests. That is, the American

Thermidor was based on the very abolition of chattel slavery – it could not, and nor did it aim

to, restore the previous ruling sub-class, the slavocracy, nor its backward labour system. At the

same time, the Northern industrial bourgeoisie – who had initiated and led the revolution –

Ch. 3: Racism, Revolution and Anti-racism, by Iggy Kim 10

sought to re-subjugate the emancipated African-Americans, but this time into a layer of extra-

cheap waged workers and a reserve labour army of poor tenant farmers. This task of revamping

racial oppression, on the rubble of the original material source of racism, chattel slavery,

necessitated a chilling new level of racist ideology. Elaborate bodies of “research”, theory and

branches of “science” (principally eugenics) flourished. Foreheads were analysed for shape and

slope, noses and skulls measured, brains weighed, all in the cause of proving the existence of

clear-cut, immutable races and the superiority of the white race. The abolitionist struggle and

the Civil War had kept at least a section of the American bourgeoisie honest for a time. Long

after its counterparts in Europe had opted for pragmatic settlements in return for economic

supremacy, the US bourgeoisie had been forced to embark on one final and risky venture in

revolutionary mass mobilisation. Then once the slave question was formally settled and the

slaveholding wing smashed, the American bourgeoisie rapidly caught up with (if not surpassed)

the rest of the European world on the race question.

But Thermidor is fundamentally an objective phenomenon – a potential danger in all

revolutions when far-reaching political gains come into conflict with divergent economic

imperatives and/or when economic transformations lag behind politics. The democratic gains of

the first American revolution were forced into a compromise because of the continued need for

slave labour, but within the very framework of the new republic – this was the essence of

Jeffersonian democracy, based on the assertion of states’ (read Southern) rights, expressed in

plebeian rhetoric. The second revolution was partially pushed back, not because the capitalist

economy was limited in its possibilities, but because its further expansion came into conflict

with a consistent expansion of bourgeois democratic rights. But Thermidor is not inevitable, for

adverse economic conditions must still be dealt with by politics – thinking human beings

engaged in the conscious political processes of organising parties, movements and their class,

exercising power, making decisions and choices. The contrast between the French-Haitian and

US methods of dealing with slavery show there is no room for fatalism, even in bourgeois

revolutions.

Thermidor, imperialism and racism

The American Thermidor was part and parcel of a new historical and developmental stage

for capital accumulation: imperialism. New advances in chemical, metallurgical, rail,

automotive, petroleum and other sectors of heavy industry toward the end of the nineteenth

century fuelled a qualitatively greater concentration of control and ownership in all the

established capitalist economies. Fewer and fewer families came to command greater chunks of

a massive new accumulation of capital. The problems of over-capacity and market saturation

now took whole economies with them. This exponentially greater scale of wealth and crisis

drove the merging of industrial and banking capital in an effort to sustain profit rates by

conglomerating all stages of economic production. Cartels and trusts were formed for the same

reason. The commanding heights of each industry and each national economy came to be

dominated by a handful of gigantic corporations. Capitalist competition spiralled upwards,

between whole economies, most abominably displayed in a global scramble for new colonies,

but this time imposing a much tighter stranglehold on the non-European world. The colonies

were no longer left as simple trading posts; they were “developed” into subordinate capitalist

economies that could deliver super-profitable returns on otherwise idle surplus capital from the

advanced countries.

American capital’s march into this epoch of monopoly and imperialism objectively required

both the second revolution and the subsequent Thermidor. The Civil War and Reconstruction

not only expanded democratic rights but, most crucially for the Northern bourgeoisie,

completed the freeing up of labour and capital required by the needs of industrial restructuring

and global capitalist competition. The very democratic rights that were needed for the bottom-

up unlocking of the Southern economy, landmass and labour force were what eventually stood

in the way of this march. The large-scale assembly lines and heavy industrial plants of the new

epoch could neither run on an inert slave labour force nor afford a large section of workers

spurred on by the fruits of a recent revolutionary victory.

This dilemma was part of a bigger one yet, for monopoly capital was also forcing an even

greater demographic shift from a farmer to a worker majority, as it simultaneously sought out

new branches of the economy to colonise and new sources of factory fodder. In this era, mass

immigration from abroad was accompanied by the internal mass migration of farming families

forced off the land. However, this demographic shift from a majority that had been small-

Ch. 3: Racism, Revolution and Anti-racism, by Iggy Kim 11

propertied and rurally bound to one that was restless and propertyless called for a wholly new

scale of social control. Alongside other forms of social division and stratification, racism proved

most effective. Thus, in this period, the scissored doling out of white privilege and black

oppression, described in the second chapter, took on a new intensity as monopoly-imperial

capitalism endowed the American bourgeoisie with the wealth to racially entrench a privileged

caste of white labour.

Abroad, racism proved just as useful in justifying imperialist plunder. The inseparable

connection between racism at home and abroad in the epoch of imperialism was made explicit

by the liberal US magazine The Nation in 1898. Commenting on a US Supreme Court decision

upholding the denial of voting rights to African-Americans in the Southern states, the article

called it “an interesting coincidence that this important decision is rendered at a time when we

are considering the idea of taking in a varied assortment of inferior races in different parts of the

world which, of course, could not be allowed to vote.”22

The period of rising imperialism was to globalise and massify a more systematic racism. In

addition to segregation in the US, this was the era of South African apartheid, the Nazi and

other fascist regimes, the White Australia Policy, and a generally deepening inequality between

what came to be known as the (predominantly white) First World and the (predominantly

coloured) Third. South Africa’s treatment of blacks was modelled on Australia’s policies toward

Aborigines; Hitler’s 1933 Hereditary Health Law was modelled on the widespread practice of

eugenics in the US. Even following Hitler’s defeat, there were still 27 US states that had laws

enforcing the sterilisation of the “unfit” and “degenerate”. All the imperialist powers were

dominated by the kind of racist ideas that, today, is confined to the far right. Mainstream

politicians, newspapers, magazines, novels, plays, scientific writings, everyday discourse were

permeated through and through by the ideology of white racial superiority, which was

considered natural and therefore righteous. The industrial barbarism of the Nazi regime was

merely the most developed form of a culture that gripped the whole of the European imperial

world.

Change was forced upon them only when the global catastrophe of the second world war

imperilled all the major imperialist powers, with the threat of mutual destruction, defeat at the

hands of expanding socialist revolutions looking to the Soviet Union, risings by colonial

peoples, or some combination of all three. Faced by this threat, all the imperialist powers

scrambled to reform their image and distance themselves from any likeness to the Nazis. No one

wanted to be left holding the rotting corpse of eugenics and racial pseudo-science as they

quickly sought to readjust to a vastly changed world situation.

The sea change of the second world war and the resulting anti-colonial revolutions had a

particularly direct, albeit contrasting impact on those colonial-settler societies where systems of

racial oppression had been a dominant and pervasive feature of all aspects of social life. On the

one hand, apartheid South Africa and Rhodesia continued to dig their heels in, thereby sharply

intensifying open – even armed – social conflict that was to engulf the whole of southern Africa

and eventually lead to the toppling of white minority rule in the last three decades of the 20th

century. On the other, the US as chief imperialist power and aegis to all imperialism, could not

afford the deepening social unrest provoked by Jim Crow. Similarly, the Australian bourgeoisie,

mindful of its growing reliance on Asian trade, was forced to turn away from the South African

path and adopt the US ruling class’s tactic of appeasement and cooption.

22

Camejo, op. cit., p. 212

Ch. 3: Racism, Revolution and Anti-racism, by Iggy Kim 12

You might also like

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5795)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1091)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Clark Atlanta University Phylon (1960-) : This Content Downloaded From 129.137.96.21 On Wed, 11 Dec 2019 19:55:51 UTCDocument10 pagesClark Atlanta University Phylon (1960-) : This Content Downloaded From 129.137.96.21 On Wed, 11 Dec 2019 19:55:51 UTCCalebXCNo ratings yet

- The Hidden History of The Second AmendmentDocument96 pagesThe Hidden History of The Second AmendmentAsanij100% (1)

- Dokumen - Pub Caribbean Slavery in The Atlantic World A Student Reader 2013nbsped 9789766377793Document1,141 pagesDokumen - Pub Caribbean Slavery in The Atlantic World A Student Reader 2013nbsped 9789766377793Brianna Perry100% (1)

- History of American JournalismDocument5 pagesHistory of American JournalismRachel QuartNo ratings yet

- President Donald Trump's 1776 Commission - Final ReportDocument45 pagesPresident Donald Trump's 1776 Commission - Final Reportcharliespiering98% (140)

- Freedom Trail - PortlandDocument4 pagesFreedom Trail - PortlandjeanscarmagnaniNo ratings yet

- Caribbean Crossing - Sara FanningDocument254 pagesCaribbean Crossing - Sara FanningKarinah MorrisNo ratings yet

- American RevolutionDocument7 pagesAmerican RevolutionRo LuNo ratings yet

- Robert Sengstacke Abbott: Chicago DefenderDocument12 pagesRobert Sengstacke Abbott: Chicago DefenderTevae ShoelsNo ratings yet

- Apush Slavery EssayDocument2 pagesApush Slavery Essayapi-342057462No ratings yet

- Roots of Radical FeminismDocument17 pagesRoots of Radical Feminismallure_chNo ratings yet

- Sankofa: African Americans in Rhode IslandDocument142 pagesSankofa: African Americans in Rhode IslandHaffenreffer Museum of Anthropology100% (2)

- Norton Anthology of American LiteratureDocument23 pagesNorton Anthology of American LiteratureErzsébet Huszár45% (11)

- Old First and Slavery, 2022Document63 pagesOld First and Slavery, 2022David StaniunasNo ratings yet

- Slavery and Pope Gregory The GreatDocument28 pagesSlavery and Pope Gregory The GreatKonstantinMorozovNo ratings yet

- The Archaeology of AntiSlavery ResistanceDocument211 pagesThe Archaeology of AntiSlavery ResistanceGarvey Lives100% (1)

- The Abolition of Brazilian Slavery 1864-1888Document25 pagesThe Abolition of Brazilian Slavery 1864-1888Emerson SoutoNo ratings yet

- Womens Suffrage MovementDocument3 pagesWomens Suffrage MovementRamoona Latif ChaudharyNo ratings yet

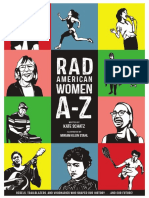

- Rad American Women A-ZDocument30 pagesRad American Women A-ZCity Lights67% (3)

- R E A D T H I S F I R S T !: Potential Short Answer Questions/Essay Topics IncludeDocument9 pagesR E A D T H I S F I R S T !: Potential Short Answer Questions/Essay Topics IncludeNOT Low-brass-exeNo ratings yet

- Written ExpressionDocument43 pagesWritten ExpressionEfi RamadhaniNo ratings yet

- Biblical Argument For SlaveryDocument15 pagesBiblical Argument For SlaveryIber AguilarNo ratings yet

- Civil War Thesis QuestionsDocument9 pagesCivil War Thesis Questionskvpyqegld100% (2)

- The Official Guide Test 8-AnswersDocument72 pagesThe Official Guide Test 8-AnswersTrân GemNo ratings yet

- Speech On The Mexican-American WarDocument4 pagesSpeech On The Mexican-American Warapi-68217851No ratings yet

- Eoc Practice Test 1Document17 pagesEoc Practice Test 1api-334758672No ratings yet

- Lawton On WedgwoodDocument280 pagesLawton On WedgwoodMartha CutterNo ratings yet

- Test 10: (5 X 2 10 PTS)Document20 pagesTest 10: (5 X 2 10 PTS)Thị Vy0% (1)

- A Narrative of Life of Frederick Douglass-Criticism of SlaveryDocument10 pagesA Narrative of Life of Frederick Douglass-Criticism of Slaverydenerys2507986100% (1)

- Abraham Lincoln's Letter To His Son's TeacherDocument4 pagesAbraham Lincoln's Letter To His Son's TeacherHuỳnh KT HươngNo ratings yet