Professional Documents

Culture Documents

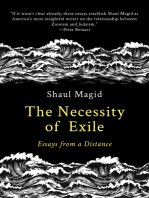

Kidney Donation: It's Complicated: Sara Kaszovitz

Uploaded by

outdash2Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Kidney Donation: It's Complicated: Sara Kaszovitz

Uploaded by

outdash2Copyright:

Available Formats

29

J

udaism places great value on human life. The Torah has many

guidelines for how a Jew should live his life, yet the Torah

believes that preservation of life is more important

than are most Torah commandments. This is evident from

the commandment that states: You shall keep My statutes and

My judgments: which if a man do, he shall live by them [1]. The

Talmud derives from this pasuk that one should live by these laws,

but not die from them, implying that one should not sacrifce his

life in order to keep the Torahs commandments [2]. The only three

laws for which one must sacrifce his life in order to avoid these

transgressions are idolatry, forbidden sexual relations, and murder

[3]. Thus, it is clear that Judaism places great emphasis on the value

of human life, and one should do the most he can to preserve his

life while still living a Torah lifestyle.

One is also required to do whatever he can in order to save a fellow

Jews life. The Torah says that you should not stand idly by the

blood of your neighbor demonstrating the Torah obligation to

save the life of any Jew who is in danger [4]. Similarly, the Talmud

states: He who saves a single life is as if he saved an entire world

[5]. Thus, it is clear that Judaism also places great emphasis on

doing whatever one can in order to save another Jew.

It is clear that the Torah charges a Jew to both do his best to

preserve ones own life and do whatever he can to save a fellow

Jews life. What would the Torah say, however, about risking ones

own life in order to save a fellow Jew? For example, would the

Torah allow someone to undergo surgery to remove a kidney and

give it to someone who is need of a kidney transplant? On the one

hand, by performing the surgery, the donor can save someone elses

life. Yet, surgery in and of itself poses risk to the donor.

Rabbi Reuven Finks article, Organ Transplants, noted that the

Talmud Yerushalmi states that one is obligated to save anothers

life from certain death, even if he may pose a danger to his own

life by doing so. He explained that commentaries elaborate that

this is because, without intervention, the victim will surely die,

and the one intervening only has the possibility of dying. Yet, the

Talmud Bavli, the more widely accepted Talmud in determining the

practice of Jewish law, states that one is not obligated to risk his

life to save another life [6]. This position is accepted lehalacha, as

noted in the commentary of the Radbaz, who writes that one is not

obligated to lose a limb to save someone elses life, but if he does

so, it is considered a pious act. He continues to say, though, that

if someone puts his life in jeopardy (i.e. a clearly greater risk than

losing a limb) to save another Jew, he is a chassid soteh, or a foolish

pious individual [6]. The Radbaz is clearly of the opinion that if one

can lose his life while attempting to save anothers life, this would be

a foolish act to perform, as Jewish law encourages one to value his

own life. Yet, the Radbaz also demonstrates that one is considered

pious for saving another Jews life, even at the risk of losing a limb,

Kidney Donation: Its Complicated

Sara Kaszovitz

refecting the Jewish value of doing whatever one can in order to

save another Jews life. Thus, when one is deciding whether or not

to try to save another individual, he should weigh the potential risks

to himself and the potential benefts of the recipient to determine

whether or not the act would be considered recommended by

Jewish law.

Donating a kidney poses two threats to the donor. First, removing

a kidney requires surgery, and there are substantial risks that come

with any surgery, certainly one of this magnitude [7]. Additionally,

although an individual can live with one kidney, physicians debate

the long-term effects removing one kidney can have, and some

suggest donating a kidney can result in a potential shortened life-

span for the donor [8].

For a kidney transplant to be successful, a few conditions must

be met. The most important condition is that the recipient has

a similar genetic makeup to that of the donor, particularly in

terms of the human leukocyte antigen (HLA) complex. The

HLA system is composed of multiple genes that make up a major

histocompatibility complex, a complex involved in monitoring ones

immune system. If the HLA system recognizes foreign antigens

(such as those of a virus) that do not match the cellular antigens

of the body, it will destroy the invading antigen. Antigens are

substances that stimulate production of antibodies. Thus, if one

receives an organ from a donor, they must have almost identical

HLA complexes to ensure that the recipients HLA system does not

fght off the donors cells of the donated organ. An HLA complex

is made up of multiple genes, and individuals vary in terms of the

makeup of this complex. Therefore, it is extremely rare to fnd two

individuals who have the same genes comprising the HLA system.

Consequently, if one is a match for an organ donation, it means

that the donor has a genetic makeup that is close enough to the

patient in need of the transplant. A match is a rare occurrence.

Therefore, if one has the ability to save another individuals life by

donating a kidney, it is a unique opportunity, and if that individual

passes up the opportunity to donate the organ, it is unlikely that

another individual will have a close enough genetic makeup to

donate the organ.

Even if someone receives a kidney from a donor with a similar

HLA complex, it is not defnitive that the transplant will be

successful. Sometimes, the body still recognizes the new organ

as foreign, and the immune system fghts off these new cells,

preventing a successful transplant. Therefore, even after donating a

kidney, one can never be sure at the outset if the transplant will be

successful or not.

The Minchat Yitzchak was asked a question as to whether a healthy

individual can donate a kidney to save someone who is ill. The

Minchat Yitzchak responded that one needs to weigh the danger

Derech Hateva

he poses to himself and how effective the transplant will be when

making this decision. If the donor will be able to continue a healthy

life, then Jewish law would encourage him to donate the organ, as

Jewish law places tremendous value on saving another individuals

life. Yet, if the individual could pose threats to his own life, and

the surgery may not be successful, Jewish law may prohibit the

donation, as one is prohibited from putting his own life in danger

[9].

From the above discussion, it is clear that kidney donation is very

complex. The results for both the donor and the recipient are not

usually known prior to the surgery. Furthermore, Jewish law is also

complicated in that it values saving someone elses life but prohibits

risking ones own life. Thus, if someone is a match for a kidney

donation he should ask a posek what to do, as kidney donation is

complicated both from a medical standpoint and from a Jewish law

standpoint.

Acknowledgments:

I would like to acknowledge Dr. Babich for his support and assistance in writing this article. I would also like to thank Rabbi Ari Zahtz and my father for

proofreading the manuscript.

References:

[1] Leviticus 18:5

[2] Yoma 85b

[3] Sanhedrin 74a

[4] Leviticus 19:16

[5] Aruch Hashulchan 426

[6] Fink, R. (1983) Halachik Aspects of Organ Transplantation. J. Halacha Contemp. Soc. 5:45-64.

[7] Breitowitz, Y. (2003) What Does Halacha Say About Organ Donation? Hlth. Med. 64: 11-12, 14-16.

[8] Halpern, M. (1991) Organ Transplants From Living Donors. Jewish Med. Ethics. 4:29-32.

[9] Shut Minchat Yitzchak 6:103:2

You might also like

- The Jewish Stance On Organ TransplantationsDocument2 pagesThe Jewish Stance On Organ TransplantationsJoel Alan KatzNo ratings yet

- The Jewish Stance On Organ Transplantations: Eliana KohanchiDocument3 pagesThe Jewish Stance On Organ Transplantations: Eliana Kohanchioutdash2No ratings yet

- EA and HalachaDocument63 pagesEA and HalachaAvraham EisenbergNo ratings yet

- Summary Guide: The Body: A Guide for Occupants: By Bill Bryson | The Mindset Warrior Summary Guide: ( Physiology, Aging, Health Intervention, Disease )From EverandSummary Guide: The Body: A Guide for Occupants: By Bill Bryson | The Mindset Warrior Summary Guide: ( Physiology, Aging, Health Intervention, Disease )Rating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- 2008 Studies of Religion Assessment TaskDocument13 pages2008 Studies of Religion Assessment TaskjazzydeecNo ratings yet

- Organ Transplant in IslamDocument17 pagesOrgan Transplant in IslamMichael WestNo ratings yet

- Organ Transplant in Islam, Two Roads of The Same PathDocument17 pagesOrgan Transplant in Islam, Two Roads of The Same Pathabduh_hafidzNo ratings yet

- UntitledDocument35 pagesUntitledoutdash2No ratings yet

- Bio EthicsDocument36 pagesBio EthicsEeshal MirzaNo ratings yet

- Muis Kidney Book ENGDocument17 pagesMuis Kidney Book ENGCrystyan CryssNo ratings yet

- Vaccine Triage in Jewish Ethics An Intermediate ApproachDocument7 pagesVaccine Triage in Jewish Ethics An Intermediate ApproachAryeh DienstagNo ratings yet

- Organ DonationDocument11 pagesOrgan DonationJakmensar Dewantara SiagianNo ratings yet

- Whose Blood Is Redder? A Halakhic Analysis of Issues Related To Separation of Conjoined TwinsDocument3 pagesWhose Blood Is Redder? A Halakhic Analysis of Issues Related To Separation of Conjoined Twinsoutdash2No ratings yet

- ETHICS OF ORGAN DONATION - Part TwoDocument10 pagesETHICS OF ORGAN DONATION - Part TwoEvang G. I. IsongNo ratings yet

- Richie Organ DonationDocument36 pagesRichie Organ DonationHema TNo ratings yet

- National Organ Donation Day: TH THDocument4 pagesNational Organ Donation Day: TH THFirasha ShaikhNo ratings yet

- Isu-Isu Kesihatan Terkini Dan Penyelesaiannya Menurut IslamDocument91 pagesIsu-Isu Kesihatan Terkini Dan Penyelesaiannya Menurut IslamKhairul AzlyNo ratings yet

- Organ DonationDocument11 pagesOrgan DonationJakmensar Dewantara SiagianNo ratings yet

- Black Markets Kill: by Jason BrennanDocument5 pagesBlack Markets Kill: by Jason BrennanshinNo ratings yet

- Eng Organ Don Essay 2Document3 pagesEng Organ Don Essay 2api-285146170No ratings yet

- Studies of Religion Notes - BioethicsDocument2 pagesStudies of Religion Notes - BioethicsNicholas RobertsNo ratings yet

- Organ Donation & Islam - A Guide To Organ Donation & Muslim Beliefs 1028Document4 pagesOrgan Donation & Islam - A Guide To Organ Donation & Muslim Beliefs 1028Crystyan CryssNo ratings yet

- Other Bioethical IssuesDocument5 pagesOther Bioethical Issuesapi-247725573No ratings yet

- Modern Miracles: Surgery in The Talmud and Today: Rikah LererDocument4 pagesModern Miracles: Surgery in The Talmud and Today: Rikah Lereroutdash2No ratings yet

- Tonguia. Docu RXNDocument5 pagesTonguia. Docu RXNFearless AngelNo ratings yet

- Answers To Section 3.7 Organ TransplantationDocument2 pagesAnswers To Section 3.7 Organ TransplantationbrownieallennNo ratings yet

- Sociology Euthanasia FDDocument18 pagesSociology Euthanasia FDParth ChowdheryNo ratings yet

- Pros and Cons of EuthanasiaDocument8 pagesPros and Cons of EuthanasiaYatin GoelNo ratings yet

- Patient AutonomyDocument11 pagesPatient AutonomyRay WoodardNo ratings yet

- EuthanasiaDocument4 pagesEuthanasiarameenakhtar993No ratings yet

- Ethical Issues Regarding The Donor and The RecipientsDocument8 pagesEthical Issues Regarding The Donor and The RecipientsArt Christian RamosNo ratings yet

- The Medical Doctor Is Confronted With A Spectrum of New Ethical Challenges As We Enter The 21st Century, Which The Authors of The Hippocratic Oath Would Not Have Anticipated. DiscussDocument11 pagesThe Medical Doctor Is Confronted With A Spectrum of New Ethical Challenges As We Enter The 21st Century, Which The Authors of The Hippocratic Oath Would Not Have Anticipated. DiscussLelon Abrey SaulNo ratings yet

- How To Achieve Blessing and Success For You and Your FamilyDocument41 pagesHow To Achieve Blessing and Success For You and Your FamilyblahqazwsxblahNo ratings yet

- Islam - BioethicsDocument29 pagesIslam - BioethicstrianaamaliaNo ratings yet

- Organ Donation EssayDocument6 pagesOrgan Donation EssayOscar Javier Rodríguez UribeNo ratings yet

- Euthanasia: Arguments and ViewpointsDocument9 pagesEuthanasia: Arguments and ViewpointsWilliam Daniel GizziNo ratings yet

- Bio Ethics IslamDocument56 pagesBio Ethics Islamapi-247725573No ratings yet

- Euthanasia Regime: A Comparative Analysis of Dutch and Indian PositionsDocument33 pagesEuthanasia Regime: A Comparative Analysis of Dutch and Indian PositionsRagita NigamNo ratings yet

- Year 12 Studies of Religion Religious Tradition Depth Study: JUDAISMDocument34 pagesYear 12 Studies of Religion Religious Tradition Depth Study: JUDAISMChamsNo ratings yet

- ETHICS OF ORGAN DONATION - AbstractDocument7 pagesETHICS OF ORGAN DONATION - AbstractEvang G. I. IsongNo ratings yet

- Why Some Jehovah's Witnesses Accept BloodDocument6 pagesWhy Some Jehovah's Witnesses Accept BloodsirjsslutNo ratings yet

- Ethics Research PaperDocument10 pagesEthics Research Paperjustine jeraoNo ratings yet

- Euthanasia: Should Euthanasia Be Legalized For Specific Cases?Document4 pagesEuthanasia: Should Euthanasia Be Legalized For Specific Cases?Kiran MishraNo ratings yet

- Euthanasia Would Not Only Be For People Who AreDocument3 pagesEuthanasia Would Not Only Be For People Who Arem__saleemNo ratings yet

- Biological Living Organism Religious Traditions Philosophical Enquiry Afterlife RebirthDocument10 pagesBiological Living Organism Religious Traditions Philosophical Enquiry Afterlife Rebirthnia coline macala mendozaNo ratings yet

- EuthanasiaDocument4 pagesEuthanasiaSukriti SinghNo ratings yet

- Euthanasia Is One of The Controversial Topics: in Medical EthicsDocument32 pagesEuthanasia Is One of The Controversial Topics: in Medical EthicsMeysam AdabNo ratings yet

- Consti ResDocument12 pagesConsti ResAdityaNo ratings yet

- Defining Life From The Perspective of Death - An Introduction To TDocument47 pagesDefining Life From The Perspective of Death - An Introduction To TChidimma StellaNo ratings yet

- Concept of Human RightsDocument12 pagesConcept of Human Rightsshiraz mehboobNo ratings yet

- Euthanasia in India: A Historical Perspective: Pankaj Sharma & Shahabuddin AnsariDocument10 pagesEuthanasia in India: A Historical Perspective: Pankaj Sharma & Shahabuddin AnsariRamseena UdayakumarNo ratings yet

- Euthanasia-White-Paper 2022 DIGITALDocument63 pagesEuthanasia-White-Paper 2022 DIGITALmagbuhoskrisenelNo ratings yet

- Arguments Against EuthanasiaDocument3 pagesArguments Against EuthanasiaThassia Salvatierra100% (1)

- International Arguments Against EuthanasiaDocument4 pagesInternational Arguments Against EuthanasiaJosh CabreraNo ratings yet

- An Argument For Physician-Assisted Suicide and AgaDocument37 pagesAn Argument For Physician-Assisted Suicide and AgamiftahulNo ratings yet

- Should We Donate Our Organs or NotDocument6 pagesShould We Donate Our Organs or NotIvanKurniawanSiagianNo ratings yet

- Zvzvdfvrttyrtaligarh Muslim University Murshidabad Centre: Study of Basic Cases of LawDocument20 pagesZvzvdfvrttyrtaligarh Muslim University Murshidabad Centre: Study of Basic Cases of LawdivyavishalNo ratings yet

- Parashas Beha'aloscha: 16 Sivan 5777Document4 pagesParashas Beha'aloscha: 16 Sivan 5777outdash2No ratings yet

- 879510Document14 pages879510outdash2No ratings yet

- 879547Document2 pages879547outdash2No ratings yet

- Chavrusa: Chag Hasemikhah ז"עשתDocument28 pagesChavrusa: Chag Hasemikhah ז"עשתoutdash2No ratings yet

- 879645Document4 pages879645outdash2No ratings yet

- The Meaning of The Menorah: Complete Tanach)Document4 pagesThe Meaning of The Menorah: Complete Tanach)outdash2No ratings yet

- The Surrogate Challenge: Rabbi Eli BelizonDocument3 pagesThe Surrogate Challenge: Rabbi Eli Belizonoutdash2No ratings yet

- Shavuot To-Go - 5777 Mrs Schechter - Qq4422a83lDocument2 pagesShavuot To-Go - 5777 Mrs Schechter - Qq4422a83loutdash2No ratings yet

- Performance of Mitzvos by Conversion Candidates: Rabbi Michoel ZylbermanDocument6 pagesPerformance of Mitzvos by Conversion Candidates: Rabbi Michoel Zylbermanoutdash2No ratings yet

- The Matan Torah Narrative and Its Leadership Lessons: Dr. Penny JoelDocument2 pagesThe Matan Torah Narrative and Its Leadership Lessons: Dr. Penny Joeloutdash2No ratings yet

- Consent and Coercion at Sinai: Rabbi Dr. Jacob J. SchacterDocument3 pagesConsent and Coercion at Sinai: Rabbi Dr. Jacob J. Schacteroutdash2No ratings yet

- Flowers and Trees in Shul On Shavuot: Rabbi Ezra SchwartzDocument2 pagesFlowers and Trees in Shul On Shavuot: Rabbi Ezra Schwartzoutdash2No ratings yet

- Shavuot To-Go - 5777 Mrs Schechter - Qq4422a83lDocument2 pagesShavuot To-Go - 5777 Mrs Schechter - Qq4422a83loutdash2No ratings yet

- Reflections On A Presidential Chavrusa: Lessons From The Fourth Perek of BrachosDocument3 pagesReflections On A Presidential Chavrusa: Lessons From The Fourth Perek of Brachosoutdash2No ratings yet

- Lessons Learned From Conversion: Rabbi Zvi RommDocument5 pagesLessons Learned From Conversion: Rabbi Zvi Rommoutdash2No ratings yet

- Kabbalat Hatorah:A Tribute To President Richard & Dr. Esther JoelDocument2 pagesKabbalat Hatorah:A Tribute To President Richard & Dr. Esther Joeloutdash2No ratings yet

- What Happens in Heaven... Stays in Heaven: Rabbi Dr. Avery JoelDocument3 pagesWhat Happens in Heaven... Stays in Heaven: Rabbi Dr. Avery Joeloutdash2No ratings yet

- The Power of Obligation: Joshua BlauDocument3 pagesThe Power of Obligation: Joshua Blauoutdash2No ratings yet

- I Just Want To Drink My Tea: Mrs. Leah NagarpowersDocument2 pagesI Just Want To Drink My Tea: Mrs. Leah Nagarpowersoutdash2No ratings yet

- Lessons From Mount Sinai:: The Interplay Between Halacha and Humanity in The Gerus ProcessDocument3 pagesLessons From Mount Sinai:: The Interplay Between Halacha and Humanity in The Gerus Processoutdash2No ratings yet

- Experiencing The Silence of Sinai: Rabbi Menachem PennerDocument3 pagesExperiencing The Silence of Sinai: Rabbi Menachem Penneroutdash2No ratings yet

- Chag Hasemikhah Remarks, 5777: President Richard M. JoelDocument2 pagesChag Hasemikhah Remarks, 5777: President Richard M. Joeloutdash2No ratings yet

- Why Israel Matters: Ramban and The Uniqueness of The Land of IsraelDocument5 pagesWhy Israel Matters: Ramban and The Uniqueness of The Land of Israeloutdash2No ratings yet

- Torah To-Go: President Richard M. JoelDocument52 pagesTorah To-Go: President Richard M. Joeloutdash2No ratings yet

- A Blessed Life: Rabbi Yehoshua FassDocument3 pagesA Blessed Life: Rabbi Yehoshua Fassoutdash2No ratings yet

- Yom Hamyeuchas: Rabbi Dr. Hillel DavisDocument1 pageYom Hamyeuchas: Rabbi Dr. Hillel Davisoutdash2No ratings yet

- 879400Document2 pages879400outdash2No ratings yet

- 879399Document8 pages879399outdash2No ratings yet

- Nasso: To Receive Via Email VisitDocument1 pageNasso: To Receive Via Email Visitoutdash2No ratings yet

- José Faur: Modern Judaism, Vol. 12, No. 1. (Feb., 1992), Pp. 23-37Document16 pagesJosé Faur: Modern Judaism, Vol. 12, No. 1. (Feb., 1992), Pp. 23-37outdash2No ratings yet

- Malaria DR TariqDocument32 pagesMalaria DR Tariqdr_hammadNo ratings yet

- RFSL Nyanlända Broschyr 2016-03-03Document32 pagesRFSL Nyanlända Broschyr 2016-03-03GnosinPortaNo ratings yet

- Atomidine 1930 Nascent Iodine UsesDocument13 pagesAtomidine 1930 Nascent Iodine Useselizabeth anne100% (2)

- Hema II Chapter 3 - Anemiarev - ATDocument154 pagesHema II Chapter 3 - Anemiarev - AThannigadah7No ratings yet

- Priscillas Medicine PDFDocument442 pagesPriscillas Medicine PDFZul Hisyam Fikri100% (1)

- Haemoglobin Levels in Patients With Oral Submucous FibrosisDocument5 pagesHaemoglobin Levels in Patients With Oral Submucous FibrosisDr Monal YuwanatiNo ratings yet

- Autoimmune HepatitisDocument13 pagesAutoimmune HepatitisVita Delfi YantiNo ratings yet

- Acute Myocardial InfarctionDocument3 pagesAcute Myocardial InfarctionKrizel Anne DeriNo ratings yet

- 2020 Article 2297 PDFDocument11 pages2020 Article 2297 PDFPamela Alejandra Marín VillalónNo ratings yet

- Subject Plan B.SC Nursing 1 Year: MicrobiologyDocument2 pagesSubject Plan B.SC Nursing 1 Year: MicrobiologySandeep KumarNo ratings yet

- Lucy Mayienga CV RecentDocument3 pagesLucy Mayienga CV Recentlucy.mayiengaNo ratings yet

- OEC CH 22Document8 pagesOEC CH 22Phil McLeanNo ratings yet

- Community Case Serhat KokenDocument12 pagesCommunity Case Serhat Kokenmaroun ghalebNo ratings yet

- MCQ FinalDocument10 pagesMCQ FinalFow 40% (1)

- Methylergonovine Med TemplateDocument1 pageMethylergonovine Med Templateel shilohNo ratings yet

- Hospital La Comunidad de Santa Rosa: Chapter I: Problem and Its SettingsDocument15 pagesHospital La Comunidad de Santa Rosa: Chapter I: Problem and Its SettingsMeynard MagsinoNo ratings yet

- 21episcleritis & ScleritisDocument11 pages21episcleritis & ScleritisNana Mu'awanahNo ratings yet

- Obstetrics and GynaecologyDocument7 pagesObstetrics and GynaecologyRashed ShatnawiNo ratings yet

- 2 Shock SyndromeDocument77 pages2 Shock SyndromelupckyNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan Reproductive SystemDocument3 pagesLesson Plan Reproductive SystemMaryJoyceReyes50% (2)

- HEMAREV Merged PDFDocument120 pagesHEMAREV Merged PDFMae BaechuNo ratings yet

- Adaptive Immunity: Shimelis Teshome (BSC MLS)Document31 pagesAdaptive Immunity: Shimelis Teshome (BSC MLS)Shimelis Teshome AyalnehNo ratings yet

- Hughes Selection of Remedy PDFDocument47 pagesHughes Selection of Remedy PDFNavya VaddimukkalaNo ratings yet

- The Diagnosis and Management of Neurofibromatosis Type 1Document20 pagesThe Diagnosis and Management of Neurofibromatosis Type 1Yeimi Nathalia Fierro PiñerosNo ratings yet

- Pantoprazole Drug StudyDocument1 pagePantoprazole Drug StudyNone Bb100% (2)

- pdf2 PDFDocument125 pagespdf2 PDFsushma shresthaNo ratings yet

- Alexa MiX RSNA2016 20170117 PDFDocument15 pagesAlexa MiX RSNA2016 20170117 PDFGodfrey EarnestNo ratings yet

- Short Course Steroids in COVID-19Document11 pagesShort Course Steroids in COVID-19drupadhyaygunjanNo ratings yet

- Cardio Nursing - Course Audit 2Document320 pagesCardio Nursing - Course Audit 2Ciella Dela CruzNo ratings yet

- Pain Management in AnimalsDocument184 pagesPain Management in Animalsssarbovan100% (1)

- Living Judaism: The Complete Guide to Jewish Belief, Tradition, and PracticeFrom EverandLiving Judaism: The Complete Guide to Jewish Belief, Tradition, and PracticeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (18)

- The Jew in the Lotus: A Poet's Rediscovery of Jewish Identity in Buddhist IndiaFrom EverandThe Jew in the Lotus: A Poet's Rediscovery of Jewish Identity in Buddhist IndiaNo ratings yet

- My Jesus Year: A Rabbi's Son Wanders the Bible Belt in Search of His Own FaithFrom EverandMy Jesus Year: A Rabbi's Son Wanders the Bible Belt in Search of His Own FaithRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (51)

- Paul Was Not a Christian: The Original Message of a Misunderstood ApostleFrom EverandPaul Was Not a Christian: The Original Message of a Misunderstood ApostleRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (13)

- The Pious Ones: The World of Hasidim and Their Battles with AmericaFrom EverandThe Pious Ones: The World of Hasidim and Their Battles with AmericaRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (7)

- Israel and the Church: An Israeli Examines God’s Unfolding Plans for His Chosen PeoplesFrom EverandIsrael and the Church: An Israeli Examines God’s Unfolding Plans for His Chosen PeoplesRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (26)

- Soul Journey through the Tarot: Key to a Complete Spiritual PracticeFrom EverandSoul Journey through the Tarot: Key to a Complete Spiritual PracticeNo ratings yet

- Kabbalah for Beginners: Understanding and Applying Kabbalistic History, Concepts, and PracticesFrom EverandKabbalah for Beginners: Understanding and Applying Kabbalistic History, Concepts, and PracticesRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (20)

- Qabbalistic Magic: Talismans, Psalms, Amulets, and the Practice of High RitualFrom EverandQabbalistic Magic: Talismans, Psalms, Amulets, and the Practice of High RitualRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (22)

- When Christians Were Jews: The First GenerationFrom EverandWhen Christians Were Jews: The First GenerationRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (56)

- DMT and the Soul of Prophecy: A New Science of Spiritual Revelation in the Hebrew BibleFrom EverandDMT and the Soul of Prophecy: A New Science of Spiritual Revelation in the Hebrew BibleRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (4)

- The Torah: The first five books of the Hebrew bibleFrom EverandThe Torah: The first five books of the Hebrew bibleRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- The Art of Happiness, Peace & Purpose: Manifesting Magic Complete Box SetFrom EverandThe Art of Happiness, Peace & Purpose: Manifesting Magic Complete Box SetRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (40)

- Divine Mathematics: Unveiling the Secrets of Gematria Exploring the Mystical & Symbolic Significance of Numerology in Jewish and Christian Traditions, & Beyond: Christian BooksFrom EverandDivine Mathematics: Unveiling the Secrets of Gematria Exploring the Mystical & Symbolic Significance of Numerology in Jewish and Christian Traditions, & Beyond: Christian BooksNo ratings yet

- Introduction Book of Zohar V1: The Science of Kabbalah (Pticha)From EverandIntroduction Book of Zohar V1: The Science of Kabbalah (Pticha)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (5)

- Wounds into Wisdom: Healing Intergenerational Jewish Trauma: New Preface from the Author, New Foreword by Gabor Mate (pending), Reading Group GuideFrom EverandWounds into Wisdom: Healing Intergenerational Jewish Trauma: New Preface from the Author, New Foreword by Gabor Mate (pending), Reading Group GuideRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Sketches of Jewish Social Life in the Days of ChristFrom EverandSketches of Jewish Social Life in the Days of ChristRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- Sitting at the Feet of Rabbi Jesus: How the Jewishness of Jesus Can Transform Your FaithFrom EverandSitting at the Feet of Rabbi Jesus: How the Jewishness of Jesus Can Transform Your FaithRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (123)

- Why the Jews?: The Reason for AntisemitismFrom EverandWhy the Jews?: The Reason for AntisemitismRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (37)

- Shamanic Qabalah: A Mystical Path to Uniting the Tree of Life & the Great WorkFrom EverandShamanic Qabalah: A Mystical Path to Uniting the Tree of Life & the Great WorkNo ratings yet

- Essential Judaism: A Complete Guide to Beliefs, Customs & RitualsFrom EverandEssential Judaism: A Complete Guide to Beliefs, Customs & RitualsRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (26)

- Kabbalah: Unlocking Hermetic Qabalah to Understand Jewish Mysticism and Kabbalistic Rituals, Ideas, and HistoryFrom EverandKabbalah: Unlocking Hermetic Qabalah to Understand Jewish Mysticism and Kabbalistic Rituals, Ideas, and HistoryRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (2)