Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Primary Predictors of Preterm Labour

Uploaded by

jft842Original Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Primary Predictors of Preterm Labour

Uploaded by

jft842Copyright:

Available Formats

Primary predictors of preterm labour

Francois Goffinet

Spontaneous preterm birth accounts for 60% of all preterm births in developed countries. With the increase in

multiple pregnancies, induced preterm birth and the progress in neonatal care for extremely preterm neonates,

spontaneous preterm birth for singleton pregnancies in developed countries has probably decreased over the

past 30 years. This decrease is likely to be related to better prenatal care for all pregnant women because the

recognition of primary risk factors in early or late pregnancy remains a basic part of prenatal care. The failure

to distinguish between induced and spontaneous preterm labour in most population-based studies makes it

difficult to interpret results with respect to the primary predictors of preterm labour. Many such primary

predictors of preterm labour have been used over the past 2030 years. These include individual factors,

socio-economic factors, working conditions and obstetric and gynaecological history. Risk scores have been

proposed in order to produce these data. Unfortunately, the predictive value of these scores, especially their

specificity, is poor, mainly because all of these factors are indirect. We still cannot identify the mechanisms

that lead to preterm labour and birth. New markers more directly related to preterm labour have recently been

proposed, some of which relate to direct causes of preterm labour such as cervical ultrasound measurement,

fetal fibronectin (FFN), salivary estriol, serum CRH and bacterial vaginosis. Several of these have predictive

values, which are potentially useful for clinical practice. Nonetheless, pregnant women in developed countries

are already closely monitored throughout pregnancy. Before proposing new screening tests to be applied

systematically to all pregnant women, their advantages and drawbacks must be fully evaluated.

INTRODUCTION

The primary predictors for spontaneous labour and preterm

birth currently used are based on either risk factors (e.g. socio-

economic, history, lifestyle) or clinical information that

becomes available during the course of pregnancy (e.g.

digital cervical examination, uterine contractions, bleed-

ing).

1,2

The benefits of considering these factors in prenatal

surveillance have not yet been demonstrated. In recent years,

newmarkers for the risk of pretermbirth have been proposed

as primary predictors in low risk populations. Although some

may be principally aetiological in nature, most are purely

symptomatic markers. They may be more relevant than

standard markers and thereby improve the efficacy of our

management of spontaneous pretermlabour by enabling more

precise and earlier diagnosis of women at very high risk.

STANDARD PRIMARY PREDICTORS OF PRETERM

LABOUR: DEMOGRAPHIC, SOCIO-ECONOMIC

AND PSYCHOSOCIAL FACTORS

Although some studies have found that women who

are short and thin before pregnancy have an increased risk

of preterm birth, this association seems less clear after

adjusting for the principal confounding factors (ethnic

group, socio-economic status, etc.).

3,4

The multivariate anal-

ysis of a prospective study, nonetheless, appears to showthat

(Caucasian) women with a low body mass index (BMI) have

an elevated risk of preterm birth.

5

Most studies report a clear association between low

maternal weight gain and preterm birth.

1,4

This effect is

not associated with hyperemesis gravidarum, which is not

associated with preterm birth.

6

Even after adjustment for the other known risk factors,

black women have a risk of preterm birth twice that of white

women.

4,5,7

A recent French study reports that preterm birth

rates are significantly higher among women born in the

overseas French districts in the Caribbean and Indian Ocean

and in sub-Saharan Africa. This study also found that this

excess risk was greatest for early preterm births.

8

Although

socio-economic and medical factors probably play a role,

this difference may be in part genetic, just as the several-

day difference in the mean duration of gestation between

black and white women is also possibly genetic.

7

Different studies define socio-economic status in various

ways, by criteria linked to education, employment or family

environment. Moreover, these criteria are highly related to

all the other demographic, ethnic and environmental factors.

Although all studies find that low socio-economic status is

associated with preterm birth,

1,3,4

it is difficult to isolate

specific risk factors. While living alone is reported to be a

risk factor for preterm birth by all studies taking it into

consideration,

9,10

it may be considered a socio-economic

marker by some and a psychosocial marker by others.

Psychological factors and lifestyle are also defined

variably in different studies. They are often based on

BJOG: an International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology

March 2005, Vol. 112, Supplement 1, pp. 3847

D RCOG 2005 BJOG: an International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology www.blackwellpublishing.com/bjog

Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Maternity

Port-Royal, Cochin-Saint Vincent-de-Paul Hospital, Paris, France

Correspondence: Professor F. Goffinet, Epidemiological Research Unit

on Women and Childrens Health, INSERM U 149, 123 Bd de Port-Royal

75014 Paris, France.

criteria related to anxiety, such as a womans attitude to-

wards her pregnancy, various life events and social sup-

port. Older studies appear contradictory, probably because

of the difficulty in measuring these criteria precisely.

4

In a

study of 2593 women, Copper et al.

11

found an association

between stress (measured on a stress scale) and preterm

birth, but the OR was only 1.16. More recent studies report

an association between preterm birth and anxiety, stress

and depression.

12

Dole et al.

13

examined a comprehensive array of psy-

chosocial factors, including life events, social support,

depression, pregnancy-related anxiety, perceived discrimi-

nation and neighbourhood safety in relation to preterm birth

(<37 weeks) in a prospective cohort study of 1962 preg-

nant women. The risk of preterm birth was elevated among

women with high levels of pregnancy-related anxiety (risk

ratio [RR] 2.1), with negative life events (RR 1.8)

and with the perception of racial discrimination (RR 1.4).

The association between high levels of pregnancy-related

anxiety and preterm birth was reduced but not eliminated

when the analysis was restricted to women without medical

comorbidities. Similarly, Haram et al.

12

found a high cor-

relation between domestic violence and major social and

lifestyle risk factors for spontaneous preterm labour.

Most recent studies show those women who are

employed have a lower risk of preterm birth.

14,15

In those

studies that control for the key confounding factors, some

characteristics related to physically or psychologically de-

manding work are associated with preterm birth.

4,1518

The EUROPOP multicentre study found that specific

working conditions affect the risk of preterm birth.

19

A

moderate excess risk (adjusted) was observed among those

who worked more than 42 hours a week (OR 1.33, CI

1.11.6), stood more than 6 hours a day (OR 1.26, CI

1.11.5) or were dissatisfied with their job (OR 1.27,

CI 1.11.5), compared with all working women.

Neither dieting nor inadequate calorie intake appears

to be associated with preterm birth. Most recent studies

report no association between anaemia and preterm birth,

except among populations from developing countries.

Some studies report associations between preterm birth

and deficiencies in iron, zinc or other minerals, but they

rarely adjust for the major confounding factors. Trials

that test mineral supplements most often reach negative

results.

4

Solid evidence shows that smoking is moderately asso-

ciated with preterm birth. The more the mother smokes, the

greater the risk.

4

It appears clear that alcohol consumption does not create

a risk of preterm birth, except in cases of very high

consumption.

4,5,20,21

A recent study in Denmark among

40,892 women found no association between preterm birth

and alcohol intake level or type of beverage drunk after

adjusting for other factors.

22

Among women who had seven

or more drinks per week, the relative risk of preterm birth

was 3.26 (95% CI 0.8013.24) (Table 1).

HISTORY

History of previous preterm birth or second trimester

pregnancy loss is the most important risk factor of preterm

birth even after adjustment for the standard confounding

factors.

1,35

This risk increases with the number of previ-

ous events. It has been proposed that this finding may be

related to cervical incompetence.

The studies on the effects of parity and of a short interval

between two pregnancies are very contradictory. Alone,

these criteria are not risk factors. However, on the other

hand, it is probable that the association is due to other fac-

tors and that only some subgroups of nulliparae or grand

multiparae are at high risk of preterm birth.

Most studies report no association between preterm

birth and a history of one or two abortions, spontaneous

or elective.

4,5

The results are contradictory, however,

when the number reaches three or more. One pathophys-

iologic hypothesis is that cervical incompetence may

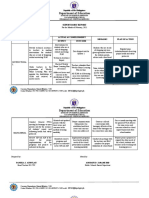

Table 1. Risk factors for preterm delivery and possibility of prevention.

Association with

spontaneous

preterm birth

Intervention

possible

Risk factors: individual,

socio-economic and behavioural

Black No

Young mother (<1519 years) Yes

Lives alone No

Domestic violence Yes

Low socio-economic status ?

Stress, depression, life events Yes

Hard work Yes

No or inadequate prenatal care Yes

Smoking, cocaine Yes

Alcohol, caffeine

Low maternal weight before pregnancy No

Weight gain during pregnancy

Short No

Gynaecological and obstetric history

Preterm delivery or second trimester

pregnancy loss

Yes

Previous cone biopsy ?

Mullerian abnormality No

Parity

Short interval between the two last

pregnancies

?

Family history (genetic factors) No

Warning signs during prenatal surveillance

IVF Yes

Multiple pregnancy Yes

Placenta praevia ?

Bleeding No

Cervicovaginal infections Yes

Uterine contractions Yes

Cervical modifications Yes

Risk scores Yes

PRIMARY PREDICTORS OF PRETERM LABOUR 39

D RCOG 2005 BJOG: an International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 112 (Suppl. 1), pp. 3847

result from trauma at the moment of the dilatation and

curettage.

The risk of preterm birth appears to be multiplied by a

factor ranging from two to five in the case of in utero

diethylstilbestrol exposure. This excess risk may be asso-

ciated with cervical or uterine malformations and with the

incompetence with which it is frequently associated.

4

Women who become pregnant as a result of IVF have a

higher risk of preterm birth, even after adjustment for the

multiple pregnancies.

4

The results are contradictory for

simple infertility. The hypotheses concern unknown under-

lying causes of infertility that may be associated with

preterm birth. Others have suggested hypotheses of greater

medical interventionism in this group of pregnancies.

PRENATAL SURVEILLANCE AND SYMPTOMS

DURING PREGNANCY

Patients with no or minimal prenatal care (few consulta-

tions, no consultation until the end of the second trimester)

have an increased risk of preterm birth.

23

This association

may be due to other factors especially common in these

women (psychosocial, economic, etc.). Programmes in-

tended to improve prenatal surveillance have reached con-

tradictory conclusions about their impact on preterm birth.

It is difficult to demonstrate a beneficial effect.

24

The U.S.

National Center for Health Statistics natality data set shows

that the absence of prenatal care is associated with elevated

preterm birth rates, after adjusting for key confounding

factors.

25

Risks range from 1.6- to 5.5-fold for different

antenatal high risk conditions.

The assessment of the number and intensity of uter-

ine contractions measured by self-palpation is very dis-

appointing because it is very poorly correlated with

monitoring.

26

Routine recording of uterine contractions

is not useful for assessing the risk of preterm birth in the

general population.

27

Although its predictive value is best in

symptomatic populations, its interest remains very limited

because a significant relation is found only very late, in the

24 hours preceding preterm birth.

28

Cervical change is associated with preterm birth.

2,29,30

In

a general population, a shortened or open cervix between

24 and 28 weeks indicates an elevated risk.

31

Significant

associations must not, however, be confused with predic-

tive value because there are many false positives and false

negatives. Various studies reach quite contradictory con-

clusions about the relevance of clinical examination as a

screening method.

31,32

The rate of false positives frequently

ranges between 20% and 60%, and false negatives be-

tween 40% and 60%. One reason is the imprecision and

lack of reproducibility of this examination. Systematic dig-

ital cervical examinations do not appear to reduce the

number of preterm births. A European randomised con-

trolled trial of 5600 women found similar rates of preterm

birth in the group that underwent an average of six digital

examinations during pregnancy, and the group with an av-

erage of one.

33

It was suggested long ago that risk scores could be used

to identify a group at high risk of preterm birth at the

beginning of pregnancy.

1,34,35

These scores use criteria

from the patients history, social background and lifestyle.

Some also considered symptoms during pregnancy. Despite

the favourable impression of the first studies, the predic-

tivity of these scores is low.

4,36,37

The likelihood ratios

found in the studies evaluating these risk scores (in the

general population) ranged from 1.3 to 8.3.

37

One reason is

that many preterm births occur in women with no risk

factors identified by standard markers.

4

In practice, sensi-

tivity is very often less than 50%, or even 25% with a

positive predictive value (PPV) between 20% and 40%.

Consequently, fewer than half the women who will give

birth preterm are identified, and most of the women with a

high risk score will undergo a large number of useless and

expensive interventions.

37

This is linked in part to the sub-

stantial weight that all these scores attribute to a history of

preterm birth, while nearly half of all preterm births occur

in nulliparae. In the American preterm prediction study,

the authors used a population of 2929 women from the gen-

eral population to construct the best possible model based

on the criteria associated with preterm birth in the study.

38

After analysis of more than 100 parameters, the criteria

retained in the model were race, history of preterm birth,

low BMI, uterine contractions in the past two weeks, vag-

inal bleeding during pregnancy and a high Bishop score.

Unfortunately, this score still identifies only a minority of

the women who will give birth preterm. The sensitivity was

24.2% for nulliparae and 18.2% for multiparae, with PPVs

of 28.6% and 33.3%, respectively.

38

NEW MARKERS AS PRIMARY PREDICTORS IN

LOW RISK POPULATIONS?

The prognostic value of the primary markers currently

available for predicting the risk of preterm birth is insuf-

ficient, and the diagnosis of preterm labour comes too late.

It is probably for these reasons that treatments based on

these markers have not reduced the number of preterm

births. These treatments are applied to many women with

only a slightly elevated risk (numerous false positives) and

not applied to many women who would have benefited

from them or who benefit too late (numerous false neg-

atives). The principal objective of developing new primary

markers is to identify more precisely the women at high

risk of preterm birth with few false positives and false

negatives. The practical advantages of those currently

under consideration are their ease of use, their reproduc-

ibility and their often modest cost. They are defined as

primary predictors because they can be used directly in an

unselected population without another screening before, for

example, the standard primary predictors.

40 F. GOFFINET

D RCOG 2005 BJOG: an International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 112 (Suppl. 1), pp. 3847

Fetal fibronectin (FFN) is an extracellular glycoprotein

located on the decidua and the fetal membranes, secreted at

the maternal fetal interface by the trophoblast, a tissue

layer formed by the cells of the outer wall of the ovum.

FFN is present in the membrane that surrounds the egg

and ensures the blastocytes adhesion to the endometrium.

Its presence in the cervicovaginal secretions, placenta and

amniotic fluid is normal through to the 20th week.

39

Once

the membranes fuse at 22 weeks, FFN is not normally

released in vaginal mucus except when the membranes

rupture, when it is found so often that it has been sug-

gested as a diagnostic test for rupture. At the end of

pregnancy, it undergoes glycosylation and loses its adhe-

sive properties. From 38 weeks of gestation onwards, it

progressively stops serving as the glue between the mem-

branes and the uterine wall.

Two mechanisms may explain the presence of FFN in

vaginal secretions in cases of spontaneous preterm labour.

The separation of the chorion from the deciduous mem-

brane of the lower uterine segment may allow its release.

Alternatively, FFN may be secreted in the cervical canal in

response to chorionic inflammation (and accompanying

proteolysis).

The assay used to measure FFN levels is performed with

a specific antibody (FDC-6), and the threshold of 50 ng/mL

seems the most useful. Its disadvantage is that the results

are not available for several hours. Some studies have

therefore assessed rapid bedside tests, some not requiring

a speculum. They have been compared with the quantita-

tive assay, but their predictive value for spontaneous

preterm labour has been assessed only rarely.

4042

These

studies show good correlation between the laboratory find-

ings and the qualitative test, but some false positives and

false negatives result from the difficulty of assessing the

borderline colorimetric results.

Numerous clinical studies have assessed the predictive

value of the FFN assay for preterm birth. Differences in the

study populations, protocols and methodological quality

make it difficult to compare results. Here we present the

results of two meta-analyses.

43,44

Both rigorously assessed

the methodology of the studies retained, especially as to

selection bias, double-blinding of the test results and the

precision of term. The inclusion period most often ran from

24 to 34 weeks; a quantitative test used 50 ng/mL as the

cutoff for a positive determination.

The predictive values of the results reported in Table 2

are good, with likelihood ratios similar to those found in

high risk populations. The predictive value is especially

interesting for preterm births before 28 and 32 weeks, as

Goldenberg et al.

45

reported in a study of nearly 3000 women.

Nonetheless, reviewing all of these studies, Khan et al.

46

showed that the authors conclusions about the diagnostic

Table 2. Adjusted OR for preterm birth related to working conditions among women working after the third month of pregnancy in three subgroups of

countries in the EUROPOP study.

Countries A-1, adjusted

OR (95% CI)

Countries A-2, adjusted

OR (95% CI)

Countries A-3, adjusted

OR (95% CI)

Total adjusted

OR (95% CI)

Term births (n) 1833 1600 616 4049

Preterm births (n) 936 859 534 2329

Weekly working hours >42 1.12 (0.81.5) 1.40 (1.01.9) 1.65 (1.02.7) 1.33 (1.11.6)

Standing position >6 hours 1.06 (0.81.3) 1.38 (1.11.7) 1.55 (1.12.3) 1.26 (1.11.5)

Dissatisfied with job 1.42 (1.11.8) 1.10 (0.81.4) 1.28 (0.81.9) 1.27 (1.11.5)

Countries A-1 child mortality rate <8 per thousand and long prenatal leaves frequent.

Countries A-2 long prenatal leaves infrequent.

Countries A-3 child mortality rate >10 per thousand and long prenatal leaves frequent.

Table 3. Characteristics and results of studies in low risk populations to

assess the prediction of delivery before 37 weeks gestation by fetal

fibronectin.

Authors (year) % PD Nb Sen Spe LR

test ()

LR

test ()

Single samples

Faron et al. (1997)

47

9.9 162 31 95 6.5 0.7

Inglis et al. (1994)

48

17.8 73 15 85 1.0 1.0

Rozenberg et al. (1996)

49

14.2 141 60 96 14.5 0.4

Goldenberg et al. (1996)

45

10.3 2929 10 98 5.0 0.9

Vercoustre (1996)

50

1.7 58 100 89 9.5 0.3

Summary LR

*

(Chien et al., 1997

43

)

3.2

(2.24.8)

0.8

(0.70.9)

Summary LR

*

(Faron et al., 1998

44

)

7.5

(4.612.3)

0.7

(0.41.0)

Serial sampling

Lockwood et al. (1993)

51

11.4 429 61 72 2.2 0.5

Hellemans et al. (1995)

52

9.6 136 54 85 3.7 0.5

Goldenberg et al. (1997)

53

9.0 1870 25 90 2.6 0.8

Greenhagen et al. (1996)

54

9.9 111 64 85 4.2 0.4

Langer (1997)

55

3.4 206 57 89 5.4 0.5

Summary LR

*

(Faron et al. 1998

44

)

3.0

(2.24.1)

0.6

(0.40.9)

PD preterm delivery before 37 weeks of gestation; Nb number of

women included in the study; Sen sensitivity; Spe specificity; LR

likelihood ratio for positive test result; LR likelihood ratio for negative

test result.

*

Summary likelihood ratios are presented with their 95% confidence

intervals. Chiens meta-analysis included three studies, Farons 4.

PRIMARY PREDICTORS OF PRETERM LABOUR 41

D RCOG 2005 BJOG: an International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 112 (Suppl. 1), pp. 3847

value of FFN met the gold standard in only 26% of cases

and that 66% of the authors over-estimated the diagnostic

value of their test.

Most studies in general populations conclude that FFN

alone does not provide enough information (Table 3).

Combining FFN with a clinical score (essentially based

on history and digital examination), Crane et al.

56

found

that the likelihood ratio increased from 3.3 with FFN alone

to more than 10 for the two tests together. Logistic

regression produces the most significant OR for the clinical

score (OR 6.9 [3.092.8]) and FFN (OR 8.0 [1.6

38.3]). Table 4 summarises the performance of the various

combinations.

The theoretical benefits of transvaginal sonography

compared with digital cervical examination are as follows:

the increased reproducibility of transvaginal sonography

examination of the complete cervix (in particular, the

supravaginal portion that cannot be explored by digital

cervical examination), and the morphology of the internal

os, which cannot always be (or is not always) explored

during digital examination.

Iams et al.

57

showed that among f3000 patients from

the general population that were evaluated twice (24 and

28 weeks), cervical length measured by transvaginal ultra-

sound was continuously associated with delivery before

35 weeks. The comparison of its predictive value with the

Bishop score seems to show a slight advantage for ultra-

sound in the various general population-based studies

(Table 5).

There has been an explosion in publications on this topic

over the past decade. Some authors conclude that this

examination should be used systematically in prenatal

surveillance. The number of publications is not synony-

mous with a definitive conclusion. Many issues make it

difficult to interpret these results. The populations studied

and study designs often differ as to whether the physicians

know the results of the test: predictive values for sim-

ilar studies can be very different. Honest et al.

62

reviewed

33 studies in asymptomatic women. They concluded that

transvaginal cervical sonography identifies women who are

at higher risk of preterm birth, although the studies vary

widely with respect to gestational age at testing and thresh-

old of abnormality. With testing at <20 weeks of gestation

and a cervical length cutoff of 25 mm, the authors reported a

summary LR of 6.29 with a corresponding LR of 0.79.

In this way, there is convincing evidence, as there is for

FFN, that a short cervix in the second trimester indicates an

increased risk of preterm birth in an unselected population.

This information does not help us decide which interven-

tion should be used.

Estriol begins to appear during the ninth week of

pregnancy, and its plasma concentration continues to in-

crease throughout the course.

63

Estrogens have been shown

to directly affect myometrial contractility, modulate the ex-

citability of myometrial cells and increase uterine sensitivity

Table 4. Combination of preterm birth risk score and fibronectin test for

prediction of preterm delivery in a low risk population (Crane et al.

56

).

*

Sen Spe PPV NPV LR

test ()

LR

test ()

Preterm birth risk score 78 80 21 98 3.9 0.3

FFN 56 83 18 96 3.3 0.5

Preterm birth risk score

and FFN

44 98 57 96 19.4 0.6

Preterm birth risk score or

FFN

89 66 15 99 2.6 0.2

Sen sensitivity; Spe specificity; PPV positive predictive value;

NPV negative predictive value; LR likelihood ratio for positive test

result; LR likelihood ratio for negative test result.

* n 140 low risk pregnant women assessed between 20 and 24 weeks of

gestation. Bacterial vaginosis was not associated with preterm delivery in

this study; preterm birth risk score included the following criteria: previous

preterm delivery, multiple gestation, suspected preterm labour, bleeding

after 12 weeks, cervical dilatation >1 cm and cervical length <1 cm.

Table 5. Comparison of the diagnostic value of cervical ultrasound and

digital cervical examination for pretermdelivery in a population at low risk.

Authors (year) % PD Nb Sen Spe LR

test ()

LR

test ()

Andersen et al. (1990)

58

18 113

lg TVS <34 mm

(25th centile)

47 84 2.9 0.6

lg clin. <15 mm

(25th centile)

36 76 1.5 0.8

Tongsong et al. (1995)

59

35 mm 12 730 66 62 1.7 0.5

Iams et al. (1996)

57

4.3

*

2915

24 weeks

cl 25 mm 37 92 4.6 0.7

cl 30 mm 54 76 2.3 0.6

protrusion 25 94 4.2 0.8

Bishop 4 28 91 3.1 0.8

28 weeks

cl 25 mm 49 87 3.8 0.6

cl 30 mm 70 68 2.2 0.4

protrusion 32 92 4.0 0.7

Bishop 4 42 82 2.3 0.7

Hasegawa et al. (1996)

60

lg 1 SD 3 729 47 85 3.1 0.6

Taipale et al.

61

2.4 3694

(1822 weeks)

lg 29 mm 19 97 6.3 0.8

IO 5 mm 16 99 16.0 0.8

cl cervical length; IOwidth internal os; SDstandard deviation; PD

delivery before 37 weeks; Nb total number of patients included in study;

Sen sensitivity; Spe specificity; LR likelihood ratio for a positive

test; LR likelihood ratio for a negative test.

Note that in this study, the comparison of the two examinations was

not performed on exactly the same women: 95 ultrasound examinations

and 72 digital cervical examinations.

*

<35 weeks.

42 F. GOFFINET

D RCOG 2005 BJOG: an International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 112 (Suppl. 1), pp. 3847

to oxytocin.

64,65

Plasma and salivary estriol levels peak three

to five weeks before labour onset both in term deliveries and

also in preterm births.

65

Fetal precursors are the source of maternal estriol and

this reinforces the hypothesis that the fetus plays a prepon-

derant role in triggering parturition. It may thus be that the

fetus responds in cases of stress or signals and initiates a

process that leads to preterm birth several weeks later.

The estriol concentration in saliva very precisely reflects

the free estriol concentration in plasma.

66

The advantages

of saliva are the ease and non-invasiveness of its collection,

the stability of the concentration during transport and a

reliable and reproducible assay technique (immunoassay).

63

McGregor et al.

65

reported a prospective study in which

salivary estriol was measured every week from 22 weeks for

241 pregnant women. The study endpoint was preterm birth

before 35 weeks, preceded by signs of spontaneous preterm

labour and without PROM (prevalence 9.5%). The authors

observed a sensitivity of 71% and a specificity of 77%

(likelihood ratio 3.1) with a cutoff point of 2.3 ng/mL. The

same team showed that this test discriminated better than

Creasys clinical score and, in a second study, that salivary

estriol identified 61% of the women who delivered preterm

within two weeks.

34,63

They conclude that this new test

might be useful in a population of asymptomatic but high

risk women in order to determine precisely which women

are really at risk of preterm birth. The noticeable advantage

over corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) is technical.

The salivary test is reliable, simple and stable but other

studies are needed before any definitive conclusion can be

made, particularly because the specificity is poor. In addi-

tion, all three existing clinical studies come from a single

team, so this new marker should be used only as part of a

research protocol.

Corticotropin-releasing hormone may play a role in pre-

term labour. Data suggest that it is involved in myometrial

contractility, through the expression of myometrial receptors

(CRH-R1 and R2), and in prostaglandin production.

67,68

Initial studies showed an association between a high CRH

level and preterm birth.

69,70

Maternal plasma CRH trajec-

tories appear to vary according to the cause of preterm

birth.

71

Clinical studies have shown that CRH produces

poor results in screening for preterm birth.

7275

Moreover,

CRH concentrations seem to be associated with numerous

factors, including ethnicity, stress and hormonal placental

modifications.

67,74

Until prospective studies using a precise

and reproducible assay technique report their results there

is, however, no point in discussing the practical use of this

marker.

To date, numerous serum markers have been reported. In

general, authors report significant associations between a

marker and preterm birth in studies with a small number

of subjects. The routine use of these markers cannot be

considered until more convincing studies are available. Re-

cent markers include maternal serum collagenase, serum

ferritin and placental alkaline phosphatase.

76,77

Any substance that, like fibronectin, is derived from

proteolytic activity and degradation of the extracellular

matrix of the choriodecidual zone around the cervix may

deserve study, and a number of such substances have been

examined. Besides cytokines, which are discussed elsewhere,

the most important of these are granulocytic elastase-a1-

antiprotease, prolactin and sialidase.

7881

A recent study

reports a significant association between preterm birth and

an elevated beta-human chorionic gonadotrophin (h-hCG)

concentration in the cervicovaginal secretions.

82

All of these

initial results call for confirmation by other studies with

more subjects.

Bacterial vaginosis (BV) is the only infectious marker

that can be used as a primary predictor in an unselected

population. Strong scientific evidence supports the exis-

tence of a relation between BV and spontaneous preterm

labour and preterm birth. In a large recent meta-analysis of

more than 20,000 women, Leitich et al.

83

report that BV

more than doubled the risk of preterm birth, and that higher

risks were reported when BV screening was performed

before 1620 weeks of gestation. Nonetheless, the studies

of the efficacy of antibiotic treatment after screening in low

risk populations are contradictory, and in the large study

of the National Institutes of Child Health and Human De-

velopment, oral metronidazole therapy did not prevent

spontaneous preterm labour and preterm birth in a mixed

population. In fact, in the high risk subgroup, it was shown to

increase it.

84,85

Infection markers are important in the battle against

preterm birth because an aetiological treatment is available

against infections. The use of these markers in current

practice is limited by their lack of simplicity, mediocre

reproducibility and high cost; all issues as fundamental in

daily practice as their capacity to identify preterm births

due to infection.

The most interesting new markers are ultrasound sonog-

raphy and fetal fibronectin, but some conditions have not

yet been met. It remains uncertain as to whether they pro-

vide any benefit over those from standard prenatal care. It

also must be remembered that adding a new screening test

before complete evaluation in everyday practice may be

harmful.

Adequate evaluation of other new markers is only be-

ginning today, and none can be proposed systematically in

prenatal surveillance.

IS THEUSEOF PRIMARYPREDICTORS EFFECTIVE?

The absence of any scientific proof of the efficacy of

these primary factors leaves many clinicians sceptical.

Studies assessing programmes to prevent preterm birth re-

port contradictory results. Several difficulties may explain

this absence of proof. Many studies combine spontaneous

and induced preterm birth, which do not respond to the

same prevention activities. In addition, the usual prevention

PRIMARY PREDICTORS OF PRETERM LABOUR 43

D RCOG 2005 BJOG: an International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 112 (Suppl. 1), pp. 3847

policies are probably only slightly (if at all) effective for

women at high risk.

31

In view of the intensive standard

prenatal surveillance currently provided and the rates of

spontaneous preterm labour and preterm birth, the effect

observed is only slight. It is also difficult, ethically and

practically, to compare two groups, one without any basic

prenatal surveillance. Until these primary factors are

replaced by more specific or even more aetiological fac-

tors, management will remain solely symptomatic and will

be needlessly applied to many patients. Current preventive

measures are ineffective or (occasionally) incorrectly ap-

plied at a regional or national scale. Finally, it is still dif-

ficult to show effects in countries where prevention policies

are especially well applied. As a result of this, the EURO-

POP multicentre study assessed and described the frequen-

cy with which work leave was prescribed in 17 countries

and studied hard work as a primary factor for preterm

births.

19

Hard work was not associated with preterm birth

in countries with policies of frequent prenatal work leave

but was significantly associated with it in other countries,

even after adjustment for other socio-economic factors

(Table 2).

Due to the absence of definitive proof, the primary

factors are not generally considered to participate in the

battle against preterm birth. It is often forgotten that the

recognition of the women at high risk within a general

population is one foundation of the current healthcare

system. These women present many psychosocial risk

factors for disorders other than preterm birth, and consid-

eration of these primary factors should allow them to be

integrated into more appropriate treatment circuits. Specific

examples show that appropriate prenatal management can

be effective in different subgroups identified on the basis of

these primary factors. In a historical study of 16,000 women,

the prevention policy for preterm birth reduced the preterm

birth rate among women at intermediate risk levels iden-

tified with standard primary predictors.

31

In an observation-

al study of 3073 low-income women, those women who

received psychosocial services had a reduced risk of low

birthweight babies, even after controlling for the number of

prenatal visits and gestational age.

86

A prenatal nutrition

and education programme for twin pregnancies reduced the

rate of preterm prelabour rupture of the membranes and

delivery before 36 weeks.

87

Other studies report an im-

proved outcome for twins associated with specialised pre-

natal care.

88,89

Two types of management can be proposed to high risk

women identified by screening with primary markers. The

first treats the cause, making it especially effective for both

prevention and treatment. This management can be offered

to very specific aetiologic subgroups, which represent only

a portion (sometimes quite small) of women among all

preterm births. Examples include cerclage for cervical

incompetence and antibiotics for infection. Such specific

treatment can never be effective for the entire group of high

risk women. Within each of these subgroups, it is probably

the most effective method for reducing the risk of preterm

birth.

The second type of management provides symptomatic

management of the threatened (or actual) preterm labour.

Nearly all cases of preterm birth are preceded by signs and

symptoms of spontaneous preterm labour. Consequently,

these symptoms, regardless of their cause, must be treated

in all cases in which it is appropriate to prolong the preg-

nancy. Randomised controlled trials of early screening

programmes for threatened preterm labour have shown an

increase in early diagnosis and, according to some authors,

a reduction in the number of preterm births.

90,91

This symp-

tomatic management (monitoring of uterine contractions at

home by a midwife, rest, tocolytics) has been the object of

much criticism, but although it does not always lead to a

reduction in the rate of preterm birth, it has reduced neo-

natal consequences, especially for extreme preterm birth.

Tocolytics prolong pregnancy for an average of several

days and therefore allow corticosteroids to be administered

and/or the mother to be transferred to a tertiary hospital

with neonatal intensive care facilities.

One reason for the ineffectiveness of treatment to reduce

preterm births is that its cause is rarely determined during

prenatal care and therefore it will remain difficult to reduce

preterm births if their causes are not acted upon. The

aetiology of preterm birth also remains difficult to define

because it is most often multifactoral, especially in the case

of spontaneous preterm labour leading to preterm birth.

92

One of the principal objectives in prevention is to discover

early aetiologic markers that would allow us to identify

subgroups of patients at high risk of preterm birth and to

manage them with more appropriate and thus more effec-

tive strategies. Recent results in this direction (e.g. infec-

tious markers, cervical ultrasound for early diagnosis of

incompetence) are encouraging.

This strategy can be effective from a public health

perspective only if it can identify as precisely as possible

the women at elevated risk among the entire population of

pregnant women. The accuracy of this screening depends

on the identification of different subgroups at risk of pre-

term birth due to different causes, with markers identified

that are appropriate to each cause.

CONCLUSION

Little progress has been made in identifying the mech-

anism at the origin of spontaneous preterm labour leading

to preterm birth, or in its treatment. Nonetheless, if we take

into account the increase in multiple pregnancies and

induced preterm birth, and the progress in neonatal care

for extremely preterm neonates, spontaneous preterm birth

for singleton pregnancies in developed countries has prob-

ably decreased over the past 30 years.

9395

This decrease in

preterm birth is undoubtedly related to better prenatal care

for all pregnant women. The recognition of primary risk

44 F. GOFFINET

D RCOG 2005 BJOG: an International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 112 (Suppl. 1), pp. 3847

factors in early or late pregnancy constitutes a part of basic

prenatal care.

New markers such as FFN and cervical ultrasound con-

stitute undeniable progress in the identification of patients

at risk of preterm birth, both in the general population and

in the population with threatened preterm birth. No man-

agement has yet been demonstrated to be effective, espe-

cially in a general population. Any recommendations for

their systematic use are precipitated. Future studies must

evaluate their advantages and disadvantages in everyday

practice. A retrospective study of 16,540 births of infants

with birthweight above the 10th centile of the reference

curves sought to determine the consequences of false

positives diagnosed with intrauterine growth retardation

(IUGR) by ultrasound.

96

The rate of preterm elective

caesarean birth was 12.7% among neonates for whom

IUGR was erroneously diagnosed, compared with 1.2%

among those for whom IUGR was not diagnosed. Associ-

ation between preterm caesarean and misdiagnosis of

IUGR still existed (OR 5.2, 95% CI 2.112.9) after

obstetric history and hypertension during pregnancy were

taken into account. This example illustrates that the assess-

ment of a diagnostic procedure must always include a prag-

matic evaluation, carried out in conditions close to those of

usual practice.

Another benefit to research on new markers is that it

improves understanding of the mechanisms of preterm la-

bour. An aetiological approach may someday lead to treat-

ments appropriate to each mechanism or cause.

References

1. Papiernik E, Kaminski M. Multifactorial study of the risk of pre-

maturity at 32 weeks of gestation. I: a study of the frequency of 30

predictive characteristics. J Perinat Med 1974;2:3036.

2. Papiernik E, Bouyer J, Collin D, Winisdoerffer G, Dreyfus J. Pre-

cocious cervical ripening and preterm labor. Obstet Gynecol 1986;

67:238242.

3. Kaminski M, Goujard J, Rumeau-Rouquette C. Prediction of low birth-

weight and prematurity by a multiple regression analysis with maternal

characteristics known since the beginning of the pregnancy. Int J

Epidemiol 1973;2:195204.

4. Berkowitz G, Papiernik E. Epidemiology of preterm birth. Epidemiol

Rev 1993;15:414443.

5. Goldenberg RL, Iams JD, Mercer BM, et al. The preterm prediction

study: the value of new vs standard risk factors in predicting early and

all spontaneous preterm births. NICHD MFMU Network. Am J Public

Health 1998;88:233238.

6. Furneaux EC, Langley-Evans AJ, Langley-Evans SC. Nausea and

vomiting of pregnancy: endocrine basis and contribution to pregnancy

outcome. Obstet Gynecol Surv 2001;56:775782.

7. Papiernik E, Alexander GR, Paneth N. Racial differences in pregnancy

duration and its implications for perinatal care. Med Hypotheses

1990;33:181186.

8. Zeitlin J, Bucourt M, Rivera L, Topuz B, Papiernik E. Preterm birth

and maternal country of birth in a French district with a multiethnic

population. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 2004;111:849855.

9. Blondel B, Zuber MC. Marital status and cohabitation during

pregnancy: relationship with social conditions, antenatal care and

pregnancy outcome in France. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 1988;2:

125137.

10. Golding J, Greenwood R, McCaw-Binns A, Thomas P. Associations

between social and environmental factors and perinatal mortality in

Jamaica. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 1994;8(Suppl 1):1739.

11. Copper RL, Goldenberg RL, Das A, et al. The preterm prediction

study: maternal stress is associated with spontaneous preterm birth at

less than thirty-five weeks gestation. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1996;

175:12861292.

12. Haram K, Mortensen JH, Wollen AL. Preterm delivery: an overview.

Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2003;82:687704.

13. Dole N, Savitz DA, Hertz-Picciotto I, Siega-Riz AM, McMahon MJ,

Buekens P. Maternal stress and preterm birth. Am J Epidemiol 2003;

157:1424.

14. Saurel-Cubizolles MJ, Kaminski M. Work in pregnancy: its evolving

relationship with perinatal outcome [a review]. Soc Sci Med 1986;

22:431442.

15. Saurel-Cubizolles MJ, Subtil D, Kaminski M. Is preterm delivery still

related to physical working conditions in pregnancy? J Epidemiol

Community Health 1991;45:2934.

16. Saurel-Cubizolles MJ, Kaminski M, Llado-Arkhipoff J, et al. Preg-

nancy and its outcome among hospital personnel according to occu-

pation and working conditions. J Epidemiol Community Health 1985;

39:129134.

17. Saurel-Cubizolles MJ, Kaminski M. Pregnant womens working con-

ditions and their changes during pregnancy: a national study in France.

Br J Ind Med 1987;44:236243.

18. Mozurkewich EL, Luke B, Avni M, Wolf FM. Working conditions

and adverse pregnancy outcome: a meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol

2000;95:623635.

19. Saurel-Cubizolles MJ, Zeitlin J, Lelong N, Papiernik E, Di Renzo GC,

Breart G. Employment, working conditions, and preterm birth: results

from the Europop case-control survey. J Epidemiol Community

Health 2004;58:395401.

20. Kaminski M, Rumeau C, Schwartz D. Alcohol consumption in preg-

nant women and the outcome of pregnancy. Alcohol Clin Exp Res

1978;2:155163.

21. Kaminski M, Franc M, Lebouvier M, du Mazaubrun C, Rumeau-

Rouquette C. Moderate alcohol use and pregnancy outcome.

Neurobehav Toxicol Teratol 1981;3:173181.

22. Albertsen K, Andersen AM, Olsen J, Gronbaek M. Alcohol

consumption during pregnancy and the risk of preterm delivery. Am

J Epidemiol 2004;159:155161.

23. Blondel B, Dutilh P, Delour M, Uzan S. Poor antenatal care and preg-

nancy outcome. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 1993;50:191196.

24. Goldenberg RL, Rouse DJ. Prevention of preterm birth [see

comments]. N Engl J Med 1998;339:313320.

25. Vintzileos AM, Ananth CV, Smulian JC, Scorza WE, Knuppel RA.

The impact of prenatal care in the United States on preterm births in

the presence and absence of antenatal high-risk conditions. Am J

Obstet Gynecol 2002;187:12541257.

26. Beckmann C, Beckman C, Stanziano G, Bergauer N, Marth C.

Accuracy of maternal perception of preterm uterine activity. Am J

Obstet Gynecol 1996;174:672675.

27. Copper RL, Goldenberg RL, Dubard MB, Hauth JC, Cutter GR.

Cervical examination and tocodynamometry at 28 weeks gestation:

prediction of spontaneous preterm birth. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1995;

172:666671.

28. Iams JD, Johnson FF, Parker M. A prospective evaluation of the

signs and symptoms of preterm labor. Obstet Gynecol 1994;84:227

230.

29. Bouyer J, Papiernik E, Dreyfus J, Collin D, Winisdoerffer B,

Gueguen S. Maturation signs of the cervix and prediction of preterm

birth. Obstet Gynecol 1986;68:209214.

30. Cabrol D. Cervical distensibility changes in pregnancy, term, and

preterm labor. Semin Perinatol 1991;15:133139.

31. Bouyer J, Papiernik E. Risk factors identified during prenatal

PRIMARY PREDICTORS OF PRETERM LABOUR 45

D RCOG 2005 BJOG: an International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 112 (Suppl. 1), pp. 3847

consultations. In: Papiernik E, Keith LG, Bouyer J, Dreyfus J, Lazar

P, editors. Effective Prevention of Preterm Birth: The French

Experience Measured at Huguenau. March of Dimes Birth Defects

Foundation. New York: White Plains, 1989;25(1).

32. Copper RL, Goldenberg RL, Davis RO, et al. Warning symptoms,

uterine contractions, and cervical examination findings in women

at risk of preterm delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1990;162:748

754.

33. Buekens P, Alexander S, Boutsen M, Blondel B, Kaminski M, Reid M.

Randomised controlled trial of routine cervical examinations in preg-

nancy. European Community Collaborative Study Group on Prenatal

Screening [see comments]. Lancet 1994;344:841844.

34. Creasy R, Gummer B, Liggins G. System for predicting spontaneous

preterm birth. Obstet Gynecol 1980;55:692696.

35. Papiernik E. Proposals for a programmed prevention policy of preterm

birth. Clin Obstet Gynecol 1984;27:614635.

36. Alexander GR, Weiss J, Hulsey TC, Papiernik E. Preterm birth pre-

vention: an evaluation of programs in the United States. Birth 1991;

18:160169.

37. McLean M, Walters WA, Smith R. Prediction and early diagnosis of

preterm labor: a critical review. Obstet Gynecol Surv 1993;48:209

225.

38. Mercer BM, Goldenberg RL, Das A, et al. The preterm prediction

study: a clinical risk assessment system. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1996;

174:18851895.

39. Lockwood CJ, Senyei AE, Dische MR, et al. Fetal fibronectin in

cervical and vaginal secretions as a predictor of preterm delivery. N

Engl J Med 1991;325:669674.

40. Parker J, Bell R, Brennecke S. Fetal fibronectin in the cervicovaginal

fluid of women with threatened preterm labour as a predictor of

delivery before 34 weeks gestation. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 1995;

35:257261.

41. Owen P, Scott A. Can fetal fibronectin testing improve the management

of preterm labour? Clin Exp Obstet Gynecol 1997;24:1922.

42. Coleman MA, McCowan LM, Pattison NS, Mitchell M. Fetal fibro-

nectin detection in preterm labor: evaluation of a prototype bedside

dipstick technique and cervical assessment. Am J Obstet Gynecol

1998;179:15531558.

43. Chien PF, Khan KS, Ogston S, Owen P. The diagnostic accuracy of

cervico-vaginal fetal fibronectin in predicting preterm delivery: an

overview. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1997;104:436444.

44. Faron G, Boulvain M, Irion O, Bernard PM, Fraser WD. Prediction of

preterm delivery by fetal fibronectin: a meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol

1998;92:153158.

45. Goldenberg RL, Mercer BM, Meis PJ, Copper RL, Das A, McNellis D.

The preterm prediction study: fetal fibronectin testing and spontaneous

preterm birth. NICHD Maternal Fetal Medicine Units Network. Obstet

Gynecol 1996;87:643648.

46. Khan KS, Khan SF, Nwosu CR, Arnott N, Chien PF. Misleading

authors inferences in obstetric diagnostic test literature. Am J Obstet

Gynecol 1999;181:112115.

47. Faron G, Boulvain M, Lescrainier JP, Vokaer A. A single cervical fetal

fibronectin screening test in a population at low risk for preterm

delivery: an improvement on clinical indicators? Br J Obstet Gynaecol

1997;104:697701.

48. Inglis SR, Jeremias J, Kuno K, et al. Detection of tumor necrosis

factor-alpha, interleukin-6, and fetal fibronectin in the lower genital

tract during pregnancy: relation to outcome. Am J Obstet Gynecol

1994;171:510.

49. Rozenberg P, Nisand I, Malagrida L, et al. Rational use of fetal

fibronectin in the evaluation of premature labor risk. J Gynecol Obstet

Biol Reprod (Paris) 1996;25:288293.

50. Vercoustre L, Sotter S, Bouige D, Walch R. Place de la fibronectine

ftal dans la prediction du travail. Resultats et commentaires a`

propos de 206 prele`vements. References Gynecol Obstet 1996;4:23

32.

51. Lockwood CJ, Wein R, Lapinski R, et al. The presence of cervical and

vaginal fetal fibronectin predicts preterm delivery in an inner-city ob-

stetric population. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1993;169:798804.

52. Hellemans P, Gerris J, Verdonk P. Fetal fibronectin detection for pre-

diction of preterm birth in low risk women. Br J Obstet Gynaecol

1995;102:207212.

53. Goldenberg RL, Mercer BM, Iams JD, et al. The preterm prediction

study: patterns of cervicovaginal fetal fibronectin as predictors of

spontaneous preterm delivery. National Institute of Child Health and

Human Development Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network. Am J

Obstet Gynecol 1997;177:812.

54. Greenhagen JB, Van Wagoner J, Dudley D, et al. Value of fetal

fibronectin as a predictor of preterm delivery for a low-risk population.

Am J Obstet Gynecol 1996;175:10541056.

55. Langer B, Boudier E, Schlaeder G. Related articles, links cervico-

vaginal fetal fibronectin: predictive value during false labor. Acta

Obstet Gynecol Scand 1997;76:218221.

56. Crane J, Armson A, Dodds L, Feinberg R, Kennedy W, Kirkland S.

Risk scoring, fetal fibronectin, and bacterial vaginosis to predict

preterm delivery. Obstet Gynecol 1999;93:517522.

57. Iams JD, Goldenberg RL, Mercer BM, et al. The length of the cervix

and the risk of spontaneous premature delivery. National Institute of

Child Health and Human Development Maternal Fetal Medicine Unit

Network. N Engl J Med 1996;334:567572.

58. Andersen HF, Nugent CE, Wanty SD, Hayashi RH. Prediction of risk

for preterm delivery by ultrasonographic measurement of cervical

length. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1990;163:859867.

59. Tongsong T, Kamprapanth P, Srisomboon J, Wanapirak C, Piyamong-

kol W, Sirichotiyakul S. Single transvaginal sonographic measurement

of cervical length early in the third trimester as a predictor of preterm

delivery. Obstet Gynecol 1995;86:184187.

60. Hasegawa I, Tanaka K, Takahashi K, Tanaka T, Aoki K, Torii Y, et al.

Transvaginal ultrasonographic cervical assessment for the prediction

of preterm delivery. J Matern Fetal Med 1996;5:305309.

61. Taipale P, Hiilesmaa V. Sonographic measurement of uterine cervix

at 18-22 weeks gestation and the risk of preterm delivery. Obstet

Gynecol 1998;92:902907.

62. Honest H, Bachmann LM, Coomarasamy A, Gupta JK, Kleijnen J,

Khan KS. Accuracy of cervical transvaginal sonography in predicting

preterm birth: a systematic review. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2003;

22:305322.

63. Heine R, McGregor J, Dullien V. Accuracy of salivary estriol testing

compared to traditional risk factor assessment in predicting preterm

birth. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1999;180:S214S218.

64. Fuchs A, Fuchs F, Husslein P, Soloff M. Oxytocin receptors in the

human uterus during pregnancy and parturition. Am J Obstet Gynecol

1984;150:734741.

65. McGregor JA, Jackson GM, Lachelin GC, et al. Salivary estriol as risk

assessment for preterm labor: a prospective trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol

1995;173:13371342.

66. Lachelin G, McGarrigle H. A comparison of saliva, plasma uncon-

jugated and plasma total oestriol throughout normal pregnancy. Br J

Obstet Gynaecol 1984;91:12031209.

67. Grammatopoulos DK, Hillhouse EW. Role of corticotropin-releasing

hormone in onset of labour. Lancet 1999;354:15461549.

68. Jirecek S, Tringler B, Knofler M, Bauer S, Topcuoglu A, Egarter C.

Detection of corticotropin-releasing hormone receptors R1 and R2

(CRH-R1, CRH-R2) using fluorescence immunohistochemistry in the

myometrium of women delivering preterm or at term. Wien Klin

Wochenschr 2003;115:724727.

69. Warren WB, Patrick SL, Goland RS. Elevated maternal plasma

corticotropin-releasing hormone levels in pregnancies complicated by

preterm labor. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1992;166:11981204 [discussion

12041207].

70. Korebrits C, Ramirez MM, Watson L, Brinkman E, Bocking AD,

Challis JR. Maternal corticotropin-releasing hormone is increased

with impending preterm birth. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1998;83:

15851591.

46 F. GOFFINET

D RCOG 2005 BJOG: an International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 112 (Suppl. 1), pp. 3847

71. McGrath S, McLean M, Smith D, Bisits A, Giles W, Smith R. Maternal

plasma corticotropin-releasing hormone trajectories vary depending

on the cause of preterm delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2002;186:

257260.

72. Leung TN, Chung TK, Madsen G, McLean M, Chang AM, Smith R.

Elevated mid-trimester maternal corticotrophin-releasing hormone

levels in pregnancies that delivered before 34 weeks. Br J Obstet

Gynaecol 1999;106:10411046.

73. McLean M, Bisits A, Davies J, et al. Predicting risk of pretermdelivery

by second-trimester measurement of maternal plasma corticotropin-

releasing hormone and alpha-fetoprotein concentrations. Am J Obstet

Gynecol 1999;181:207215.

74. Holzman C, Jetton J, Siler-Khodr T, Fisher R, Rip T. Second trimester

corticotropin-releasing hormone levels in relation to preterm delivery

and ethnicity. Obstet Gynecol 2001;97:657663.

75. Inder WJ, Prickett TC, Ellis MJ, et al. The utility of plasma CRH as a

predictor of preterm delivery. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2001;86:

57065710.

76. Tamura T, Goldenberg RL, Johnston KE, Cliver SP, Hickey CA.

Serum ferritin: a predictor of early spontaneous preterm delivery.

Obstet Gynecol 1996;87:360365.

77. Faron G. Depistage de laccouchement avant terme. Realites et

perspectives. Gynecol Intern 1998;7:269276.

78. Kanayama N, Terao T. The relationship between granulocyte

elastase-like activity of cervical mucus and cervical maturation. Acta

Obstet Gynecol Scand 1991;70:2934.

79. Jotterand AD, Caubel P, Guillaumin D, Augereau F, Chitrit Y,

Boulanger MC. Predictive value of cervical-vaginal prolactin in the

evaluation of premature labor risk. J Gynecol Obstet Biol Reprod

(Paris) 1997;26:9599.

80. Andrews WW, Tsao J, Goldenberg RL, et al. The preterm prediction

study: failure of midtrimester cervical sialidase level elevation to

predict subsequent spontaneous preterm birth. Am J Obstet Gynecol

1999;180:11511154.

81. Arinami Y, Hasegawa I, Takakuwa K, Tanaka K. Prediction of

preterm delivery by combined use of simple clinical tests. J Matern

Fetal Med 1999;8:7073.

82. Bernstein PS, Stern R, Lin N, et al. Beta-human chorionic

gonadotropin in cervicovaginal secretions as a predictor of preterm

delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1998;179:870873.

83. Leitich H, Bodner-Adler B, Brunbauer M, Kaider A, Egarter C,

Husslein P. Bacterial vaginosis as a risk factor for preterm delivery: a

meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2003;189:139147.

84. Carey JC, Klebanoff MA, Hauth JC, et al. Metronidazole to prevent

preterm delivery in pregnant women with asymptomatic bacterial

vaginosis. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development

Network of Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units. N Engl J Med 2000;342:

534540.

85. Ugwumadu A, Manyonda I, Reid F, Hay P. Effect of early oral

clindamycin on late miscarriage and preterm delivery in asymptomatic

women with abnormal vaginal flora and bacterial vaginosis: a ran-

domised controlled trial. Lancet 2003;361:983988.

86. Zimmer-Gembeck MJ, Helfand M. Low birthweight in a public pre-

natal care program: behavioral and psychosocial risk factors and

psychosocial intervention. Soc Sci Med 1996;43:187197.

87. Luke B, Brown MB, Misiunas R, et al. Specialized prenatal care and

maternal and infant outcomes in twin pregnancy. Am J Obstet

Gynecol 2003;189:934938.

88. Vergani P, Ghidini A, Bozzo G, Sirtori M. Prenatal management of

twin gestation. Experience with a new protocol. J Reprod Med 1991;

36:667671.

89. Ellings JM, Newman RB, Hulsey TC, Bivins Jr HA, Keenan A.

Reduction in very low birth weight deliveries and perinatal mortality

in a specialized, multidisciplinary twin clinic. Obstet Gynecol 1993;

81:387391.

90. Colton T, Kayne H, Zhang Y, Heeren T. A metaanalysis of home

uterine activity monitoring. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1995;173:14991505.

91. Corwin MJ, Mou SM, Sunderji SG, et al. Multicenter randomized

clinical trial of home uterine activity monitoring: pregnancy outcomes

for all women randomized. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1996;175:12811285.

92. Cabrol D. Classification of the risks of premature labor. Implications

for treatment. J Gynecol Obstet Biol Reprod (Paris) 1997;26(Suppl 2):

69.

93. Breart G, Blondel B, Tuppin P, Grandjean H, Kaminski M. Did

preterm deliveries continue to decrease in France in the 1980s?

Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 1995;9:296306.

94. Blondel B, Norton J, du Mazaubrun C, Breart G. Development of the

main indicators of perinatal health in metropolitan France between

1995 and 1998. Results of the national perinatal survey. J Gynecol

Obstet Biol Reprod (Paris) 2001;30:552564.

95. Papiernik E, Zeitlin J, Rivera L, Bucourt M, Topuz B. Preterm birth in

a French population: the importance of births by medical decision. Br

J Obstet Gynaecol 2003;110:430432.

96. Ringa V, Carrat F, Blondel B, Breart G. Consequences of mis-

diagnosis of intrauterine growth retardation for preterm elective

cesarean section. Fetal Diagn Ther 1993;8:325330.

PRIMARY PREDICTORS OF PRETERM LABOUR 47

D RCOG 2005 BJOG: an International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 112 (Suppl. 1), pp. 3847

You might also like

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Hernia EmergenciesDocument34 pagesHernia Emergenciesjft842No ratings yet

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Guidelines BronchitisDocument9 pagesGuidelines Bronchitisjft842No ratings yet

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Hirschsprung Associated Enterocolitis Pathogenesis, Treatment, and PreventionDocument9 pagesHirschsprung Associated Enterocolitis Pathogenesis, Treatment, and Preventionjft842No ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Acute Bronchitis 2010Document6 pagesAcute Bronchitis 2010Yaz TongeNo ratings yet

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Clinical Report-Fever and Antipyretic Usi in Children PDFDocument10 pagesClinical Report-Fever and Antipyretic Usi in Children PDFdeventaNo ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- ResultadosDocument27 pagesResultadosjft842No ratings yet

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Treatment of Pediculosis Capitis - A Critical Appraisal of The Current LiteratureDocument12 pagesTreatment of Pediculosis Capitis - A Critical Appraisal of The Current Literaturejft842No ratings yet

- Treatment of Pediculosis Capitis - A Critical Appraisal of The Current LiteratureDocument12 pagesTreatment of Pediculosis Capitis - A Critical Appraisal of The Current Literaturejft842No ratings yet

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Soundforgepromac 2.0 Manual EnuDocument112 pagesSoundforgepromac 2.0 Manual Enujft842No ratings yet

- Preconception of InfertilkiftyDocument9 pagesPreconception of Infertilkiftyjft842No ratings yet

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Pathogenesis of Hirschprung Disease Associated EnterocolitisDocument9 pagesThe Pathogenesis of Hirschprung Disease Associated Enterocolitisjft842No ratings yet

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- BMJ Open 2013 MorganDocument8 pagesBMJ Open 2013 Morganjft842No ratings yet

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- BMJ Open 2013 MorganDocument8 pagesBMJ Open 2013 Morganjft842No ratings yet

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Syphilis in Pregnancy: ReviewDocument8 pagesSyphilis in Pregnancy: Reviewjft842No ratings yet

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Prediction of Preterm Birth Cervical SonographyDocument8 pagesPrediction of Preterm Birth Cervical Sonographyjft842No ratings yet

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Sperm Retrieval 2011Document14 pagesSperm Retrieval 2011xexeuzinhoNo ratings yet

- Gynecologic Laparoscopy in Patients Aged 65 or More Feasibility and Safety in The Presence of Increased ComorbidityDocument5 pagesGynecologic Laparoscopy in Patients Aged 65 or More Feasibility and Safety in The Presence of Increased Comorbidityjft842No ratings yet

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Vulvar ProceduresDocument14 pagesVulvar Proceduresjft842No ratings yet

- fpm20060400p41 rt2Document1 pagefpm20060400p41 rt2Deepak DahiyaNo ratings yet

- A Comparison Between Ultrasonography and Hysteroscopy in TheDocument3 pagesA Comparison Between Ultrasonography and Hysteroscopy in Thejft842No ratings yet

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Power Plant Setting Company in CGDocument6 pagesPower Plant Setting Company in CGdcevipinNo ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Soni Musicae Diato K2 enDocument2 pagesSoni Musicae Diato K2 enknoNo ratings yet

- Raising CapitalDocument43 pagesRaising CapitalMuhammad AsifNo ratings yet

- Ulcerativecolitis 170323180448 PDFDocument88 pagesUlcerativecolitis 170323180448 PDFBasudewo Agung100% (1)

- Supplementary: Materials inDocument5 pagesSupplementary: Materials inEvan Siano BautistaNo ratings yet

- The Economic Report of The PresidentDocument35 pagesThe Economic Report of The PresidentScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Script For My AssignmentDocument2 pagesScript For My AssignmentKarylle Mish GellicaNo ratings yet

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (120)

- Ganendra Art House: 8 Lorong 16/7B, 46350 Petaling Jaya, Selangor, MalaysiaDocument25 pagesGanendra Art House: 8 Lorong 16/7B, 46350 Petaling Jaya, Selangor, MalaysiaFiorela Estrella VentocillaNo ratings yet

- Gas StoichiometryDocument9 pagesGas StoichiometryJoshua RomeaNo ratings yet

- Science Camp Day 1Document13 pagesScience Camp Day 1Mariea Zhynn IvornethNo ratings yet

- Oracle E-Business Suite TechnicalDocument7 pagesOracle E-Business Suite Technicalmadhugover123No ratings yet

- Ch05 P24 Build A ModelDocument5 pagesCh05 P24 Build A ModelKatarína HúlekováNo ratings yet

- Distribution of BBT EbooksDocument7 pagesDistribution of BBT EbooksAleksandr N ValentinaNo ratings yet

- Political Law Reviewer Bar 2019 Part 1 V 20 by Atty. Alexis Medina ACADEMICUSDocument27 pagesPolitical Law Reviewer Bar 2019 Part 1 V 20 by Atty. Alexis Medina ACADEMICUSalyamarrabeNo ratings yet

- Tray Play Ebook PDFDocument60 pagesTray Play Ebook PDFkaren megsanNo ratings yet

- Operant Conditioning of RatsDocument7 pagesOperant Conditioning of RatsScott KaluznyNo ratings yet

- Plotting A Mystery NovelDocument4 pagesPlotting A Mystery NovelScott SherrellNo ratings yet

- Special Power of Attorney 2017-Michael John Dj. OpidoDocument2 pagesSpecial Power of Attorney 2017-Michael John Dj. OpidoJhoanne BautistaNo ratings yet

- Sample Activity ReportDocument2 pagesSample Activity ReportKatrina CalacatNo ratings yet

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Periyava Times Apr 2017 2 PDFDocument4 pagesPeriyava Times Apr 2017 2 PDFAnand SNo ratings yet

- Finance Management Individual AssDocument33 pagesFinance Management Individual AssDevan MoroganNo ratings yet

- Department of Education: Supervisory Report School/District: Cacawan High SchoolDocument17 pagesDepartment of Education: Supervisory Report School/District: Cacawan High SchoolMaze JasminNo ratings yet

- Nestle Philippines, Inc., v. PuedanDocument1 pageNestle Philippines, Inc., v. PuedanJoycee ArmilloNo ratings yet

- How To Write SpecificationsDocument9 pagesHow To Write SpecificationsLeilani ManalaysayNo ratings yet

- Kaulachara (Written by Guruji and Posted 11/3/10)Document4 pagesKaulachara (Written by Guruji and Posted 11/3/10)Matt Huish100% (1)

- The Achaeans (Also Called The "Argives" or "Danaans")Document3 pagesThe Achaeans (Also Called The "Argives" or "Danaans")Gian Paul JavierNo ratings yet

- Syllabus Mathematics (Honours and Regular) : Submitted ToDocument19 pagesSyllabus Mathematics (Honours and Regular) : Submitted ToDebasish SharmaNo ratings yet

- Lectra Fashion e Guide Nurturing EP Quality Logistics Production Crucial To Optimize enDocument8 pagesLectra Fashion e Guide Nurturing EP Quality Logistics Production Crucial To Optimize eniuliaNo ratings yet

- Unit 9 Performance Planning and Review: ObjectivesDocument16 pagesUnit 9 Performance Planning and Review: ObjectivesSatyam mishra100% (2)

- Barnum Distributors Wants A Projection of Cash Receipts and CashDocument1 pageBarnum Distributors Wants A Projection of Cash Receipts and CashAmit PandeyNo ratings yet

- LIT: Life Ignition Tools: Use Nature's Playbook to Energize Your Brain, Spark Ideas, and Ignite ActionFrom EverandLIT: Life Ignition Tools: Use Nature's Playbook to Energize Your Brain, Spark Ideas, and Ignite ActionRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (403)

- Raising Mentally Strong Kids: How to Combine the Power of Neuroscience with Love and Logic to Grow Confident, Kind, Responsible, and Resilient Children and Young AdultsFrom EverandRaising Mentally Strong Kids: How to Combine the Power of Neuroscience with Love and Logic to Grow Confident, Kind, Responsible, and Resilient Children and Young AdultsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Think This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeFrom EverandThink This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeNo ratings yet