Professional Documents

Culture Documents

1 - 3 - Video 1.3 - The Oldest Reference To Israel (8 - 58)

Uploaded by

John W Holland0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

33 views5 pagesThe Bible's Prehistory, Purpose, and Political Future

by Dr. Jacob L. Wright

Original Title

1 - 3 - Video 1.3_ the Oldest Reference to Israel (8_58)

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

TXT, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentThe Bible's Prehistory, Purpose, and Political Future

by Dr. Jacob L. Wright

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as TXT, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

33 views5 pages1 - 3 - Video 1.3 - The Oldest Reference To Israel (8 - 58)

Uploaded by

John W HollandThe Bible's Prehistory, Purpose, and Political Future

by Dr. Jacob L. Wright

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as TXT, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 5

So the question that we're now asking is,

how did it all begin?

Where does Israel come from and how did

the states of Israel and Judah develop.

Okay, so.

Let's ask first, what is the first

historical reference to Israel, outside

the Bible?

That is, what is the first reference to

the name, Israel, explicitly in a text.

That is in Egypt, Mesopotamia, wherever.

And many of you may know the answer to

this question already.

The date is about 1200 BC.

And the place where it was discovered, the

text, is the town of

Thebes, way down in southern Egypt, about

800 kilometers south of the Mediterranean

coast.

Now before I describe this remarkable

reference

to Israel, I want to point out that

that we have much older Egyptian texts

that

mention the names of places that would

become.

Important towns in Israel's history.

These are the names of places in Canaan,

Israel

had not yet developed, but in Canaan, in

Southern Canaan.

And that will endure for many centuries

thereafter, in

the times of the Biblical kings and so

forth.

So one source for these references is the

Execration Texts, dating

to Egypt's twelfth dynasty, that is about

the nineteenth century B.C..

The Execration texts are really

fascinating, really fascinating.

Some are on pottery shards, like broken

pieces

of pottery and others are on figurines and

as a kind of sympathetic magic the names

of the enemies of the individual peoples,

places, whatever.

In this case the towns of Canaan.

Were written upon these objects and then

they were ceremonially

destroyed as curses were pronounced over

their names and crashed down.

The idea is that the ritual and the

curse would ensure that these Canaanite

towns would not

pose a threat to the Egyptian ruler, and

one

did that through this curse and through

these ceremonies.

You might be thinking of similar practices

when you hear about this.

That you know of in other cultures, in

other times and places.

And if you do, please mention them in the

discussion.

I would love to hear about them.

So one of these texts, one of

these execration texts, mentions the word

ushalim.

And some scholars identify it with the

name.

Jerusalem, Jerusalem in hebrew is

[FOREIGN].

And [FOREIGN] do sound similar.

Others.

however, are not convinced by this

reading.

So we shouldn't make too much of it.

So what's interesting for our course is

the context of these

first references to important towns from

the land of the Bible.

And the context is defeat.

And curses calling for the destruction of

these places and their inhabitants.

It's quite fascinating.

Now, the second corpus of Egyptian text

mentions

places we know from the Bible as well.

And this corpus is in fact our more

important source

of knowledge of activities in Canaan in

the period directly before.

The many historical changes that gave rise

to the kingdoms of Israel and Judah.

We call this text the Armana Letters after

the

town of L Armana in Southern Egypt, the

Armana Letters.

It was there that this guy the

thing which Egyptologist and archaeologist

Flinders Petrie.

Found a collection of about 350 letters.

The year was 1887 and in these letters,

several

Egyptian rulers from Amenhotep III, the

King Tut who reigned

in the fourteenth century, correspond back

and forth with powerful

rulers in the areas of what are now modern

Syria.

Turkey and Iraq.

However, the Egyptian kings also write to

their town mayors.

That is, men whom they had appointed to

oversee numerous towns throughout Canaan.

And, they're kind of their governors, or

in their provinces, kind of thing.

In their epistle to the Egyptian court,

these local rulers, these mayors.

And towns such as Shkem, Shkem or

Jerusalem, Makido, Gezer, Hebron or Hebron

report many

juicy details about their struggles with

mayors in

competing towns, and they're very fun to

read.

We'll return to them [INAUDIBLE] letters

later since

they help us imagine what would have

happened.

When Egypt relinquished its attempt to

exert control over Canaan, the

land of the Bible, and it's very important

for that point.

So now, what about the most important

reference to

Israel, which was discovered at the town

of Thebes?

The reference is found on a royal monument

of victory.

Called the Merneptah Stele.

A stele is a big stone that is erected.

And it's named after the Egyptian king

Merneptah, who ruled until about 1203 BC.

The monument is inscribed with a text.

And the text is an account of this ruler's

military campaign.

Against Libya in the south of Egypt.

Now at the end of the text are three lines

that treat another military campaign.

This one into Caanan, in the north.

Now, let me read for you the culmination

of the

section of these three lines as translated

by Miriam Lichtiem.

The princes are prostrate saying, Shalom.

Not one of the Nine Bows lifts his head.

Tjehenu is vanquished, Khatti at peace,

Canaan is captive with all woe.

Askelon is conquered, Gezer seized, Yanoam

made nonexistent and here.

Israel is wasted, bare of seed, and then

Khor is become a widow for Egypt.

All who roamed about have been subdued by

the king of upper and lower Egypt.

Now, the first thing to notice is that

when we examine the hieroglyphs, that is

the Egyptian

writing signs, we can see that Ashkelon,

Gezer and

Yanoam have a marker or what's called a

determinative.

That is used before cities.

It's a throw stick plus three mountains.

In contrast the determinative the sign

used for Israel, right before

Israel is a throw stick followed by a

sitting man and a

sitting woman above the plural marker, the

three vertical lines, but

it does not have the three mountains, as

you can see here.

This determinative appears before foreign

peoples

who are typically nomadic, rather than

urban.

That is, they're not city dwellers.

So Israel is not being noted here as a

city, but rather as a people without a

urban center.

Okay?

Now second.

What we're told about this nomadic

population

called Israel is that they are defeated.

Literally, they are wasted, their seed is

not.

The word for seed, [FOREIGN] could refer

either to Israel's corn and

crops, or it could be a way of describing

their biological seed.

Either way, the point is the same, that

the Egyptian King had destroyed their

means of survival.

We probably should not take the phrase too

literally, since the scribe

was likely attempting to find a poetic way

of des, of describing conquest.

It would be similar to the following in

line that

I just read, whore has becomes as a widow

for Egypt.

This poetry 'Kay?

And the describer's trying to find

different ways of describing conquest.

Less it would be too much to claim as

some have, that is, rural is being

describe here

as quote, a rural or sedentary group of

agriculturalists,

that is, farmers, without its own urban

city-state support system.

This is a quote from Michael Hasel.

We also can not say where these people,

where these the people of

Israel are located other than that they

are somewhere in the southern Levant.

That is, in the land of the Bible, but

even that is not for sure.

They could have been in the trans Jordan

that is the

modern Jordan, and so we really don't even

know where they're located.

But what's interesting for the theme of

our course, which is how Israel reinvented

itself after defeat is, number one, the

name of Israel is attested for

the first time outside the Bible in an

inscription from 1200 B.C.E. Number

two, the inscription refers to Israel as a

non-urban population, not yet a state.

Perhaps nomadic in lifestyle, and most

importantly number 3, this

first reference to Israel claims that it

has been defeated.

That it's seed is no longer.

If this last point were taken at face

value, then we can stop the course right

here.

But, the historical facts prove to be much

more complex.

than the monument to King Ramentes

Triumph.

Israel was not wiped out.

It survived.

And as we shall see in coming lectures, it

went on to thrive.

And to build a state in a society that

lasted for several centuries.

Before another foreign empire destroyed

it.

But even then, conquest was not the final

word.

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Revolu On%of%the RTHDocument12 pagesRevolu On%of%the RTHJohn W HollandNo ratings yet

- From%the%Big NG To Rk%energy: Hitoshi MurayamaDocument9 pagesFrom%the%Big NG To Rk%energy: Hitoshi MurayamaJohn W HollandNo ratings yet

- Lecture - Slides W1 2 Day and NightDocument15 pagesLecture - Slides W1 2 Day and Nightcigdem1985No ratings yet

- Why%ellip C?Document11 pagesWhy%ellip C?John W HollandNo ratings yet

- Beginning"of"the"universe Look"far"into"the"pastDocument33 pagesBeginning"of"the"universe Look"far"into"the"pastJohn W HollandNo ratings yet

- Why%does%everything Fall%the%same%way?Document8 pagesWhy%does%everything Fall%the%same%way?John W HollandNo ratings yet

- Andromeda 2.5M%Lyr%Away Also rk%Mayer%Important: Credit:%NasaDocument13 pagesAndromeda 2.5M%Lyr%Away Also rk%Mayer%Important: Credit:%NasaJohn W HollandNo ratings yet

- 1-7 The Importance of Sleep in LearningDocument5 pages1-7 The Importance of Sleep in LearningJohn W HollandNo ratings yet

- 1-1 Introduction To The Focused and Diffuse ModesDocument6 pages1-1 Introduction To The Focused and Diffuse ModesJohn W HollandNo ratings yet

- Cluster%of%galaxies: Abell"18 2.1b%lyrsDocument12 pagesCluster%of%galaxies: Abell"18 2.1b%lyrsJohn W HollandNo ratings yet

- Penzias & WilsonDocument20 pagesPenzias & WilsonJohn W HollandNo ratings yet

- 1-9 Summary of Week 1Document11 pages1-9 Summary of Week 1John W HollandNo ratings yet

- Cosmic%expansionDocument18 pagesCosmic%expansionJohn W HollandNo ratings yet

- Distant Stars and Galaxies Appear Red: Approaching: Pitch Receding: Pitch Receding Stars: ColorDocument22 pagesDistant Stars and Galaxies Appear Red: Approaching: Pitch Receding: Pitch Receding Stars: ColorJohn W HollandNo ratings yet

- 1-7 The Importance of Sleep in LearningDocument5 pages1-7 The Importance of Sleep in LearningJohn W HollandNo ratings yet

- 1-5 Practice Makes PermanentDocument12 pages1-5 Practice Makes PermanentJohn W HollandNo ratings yet

- 1-6 Introduction To MemoryDocument13 pages1-6 Introduction To MemoryJohn W HollandNo ratings yet

- 1-3A What Is LearningDocument5 pages1-3A What Is LearningJohn W HollandNo ratings yet

- 1-4 A Procrastination PreviewDocument6 pages1-4 A Procrastination PreviewJohn W HollandNo ratings yet

- 1-3A What Is LearningDocument5 pages1-3A What Is LearningJohn W HollandNo ratings yet

- 1-3 Using The Focused and Diffuse Modes - or A Little Dali Will Do YouDocument5 pages1-3 Using The Focused and Diffuse Modes - or A Little Dali Will Do YouJohn W HollandNo ratings yet

- 1-3A What Is LearningDocument5 pages1-3A What Is LearningJohn W HollandNo ratings yet

- 1-4 A Procrastination PreviewDocument6 pages1-4 A Procrastination PreviewJohn W HollandNo ratings yet

- 1 - 4 - Video 1.4 - The Centers of Civilization (5 - 42)Document3 pages1 - 4 - Video 1.4 - The Centers of Civilization (5 - 42)John W HollandNo ratings yet

- 1 - 6 - Video 1.6 - Egypt - 'S Presence in Canaan During The New Kingdom (11 - 46)Document7 pages1 - 6 - Video 1.6 - Egypt - 'S Presence in Canaan During The New Kingdom (11 - 46)John W HollandNo ratings yet

- 1-3 Using The Focused and Diffuse Modes - or A Little Dali Will Do YouDocument5 pages1-3 Using The Focused and Diffuse Modes - or A Little Dali Will Do YouJohn W HollandNo ratings yet

- 1-1 Introduction To The Focused and Diffuse ModesDocument6 pages1-1 Introduction To The Focused and Diffuse ModesJohn W HollandNo ratings yet

- 1 - 2 - Video 1.2 - Defeat and The Response To Defeat (2 - 52)Document2 pages1 - 2 - Video 1.2 - Defeat and The Response To Defeat (2 - 52)John W HollandNo ratings yet

- 1 - 5 - Video 1.5 - The Levant As A Land Bridge (6 - 39)Document4 pages1 - 5 - Video 1.5 - The Levant As A Land Bridge (6 - 39)John W HollandNo ratings yet

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- College of Nursing (Female) Shaheed BenazirabadDocument4 pagesCollege of Nursing (Female) Shaheed BenazirabadUzairNo ratings yet

- Script For EDSA Revolution PlayDocument3 pagesScript For EDSA Revolution PlayMaybelyn de los ReyesNo ratings yet

- Epitheta Deorum, Quae Apud Poetas Latinos leguntur-CARTER-1902Document174 pagesEpitheta Deorum, Quae Apud Poetas Latinos leguntur-CARTER-1902FabianaNo ratings yet

- Mhatellist PDFDocument23 pagesMhatellist PDFAbhishek Dutt IntolerantNo ratings yet

- Lista de Precios Intek l2021 C - Fotos (29 Dic)Document568 pagesLista de Precios Intek l2021 C - Fotos (29 Dic)Carmen Gloria Poblete OrmeñoNo ratings yet

- 8Document22 pages8Hassan RizwanNo ratings yet

- SoccerDocument3 pagesSoccerChoelie RuizNo ratings yet

- (DS) Asistencia Sensibilización e Inducción A La NormaDocument7 pages(DS) Asistencia Sensibilización e Inducción A La NormaDEISY LOPEZNo ratings yet

- All Because of Jesus Chords Key of GDocument1 pageAll Because of Jesus Chords Key of GLiza-Anne RobertsNo ratings yet

- 100 Books To Read: The Da Vinci Code - Dan BrownDocument2 pages100 Books To Read: The Da Vinci Code - Dan BrownHeather StathamNo ratings yet

- 11 Interesting Facts About The Prophet SamuelDocument4 pages11 Interesting Facts About The Prophet SamuelJessy MalcolmNo ratings yet

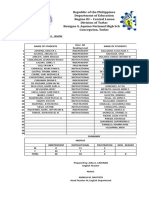

- Pre TestDocument6 pagesPre TestAngie Diño AmuraoNo ratings yet

- List of The Eligible CandidatesDocument37 pagesList of The Eligible CandidatesUjjwal SalathiaNo ratings yet

- 7BDocument1 page7BsirajuddinNo ratings yet

- Status As Per Grade PayDocument2 pagesStatus As Per Grade Payborderroads100% (3)

- Hilmar - Farid-Batjaan Liar in The Dutch East IndiesDocument16 pagesHilmar - Farid-Batjaan Liar in The Dutch East IndiesInstitut Sejarah Sosial Indonesia (ISSI)100% (1)

- 6000 Ds KH Vinhomes Gardenia My DinhDocument300 pages6000 Ds KH Vinhomes Gardenia My Dinhphương maiNo ratings yet

- Indigenous Peoples of The Americas - WikipediaDocument21 pagesIndigenous Peoples of The Americas - WikipediaRegis MontgomeryNo ratings yet

- Hamdan Bin Mohammed Al Maktoum: Jump To Navigation Jump To SearchDocument3 pagesHamdan Bin Mohammed Al Maktoum: Jump To Navigation Jump To SearchIon ArtinNo ratings yet

- Philippine Mythology God and GoddessDocument3 pagesPhilippine Mythology God and GoddessJonalyn BuhisanNo ratings yet

- List of Candidates Selected On Open Merit Seats For Rawalpindi Medical College, Rawalpindi For The Session 2015-2016 (30th October 2015)Document28 pagesList of Candidates Selected On Open Merit Seats For Rawalpindi Medical College, Rawalpindi For The Session 2015-2016 (30th October 2015)MarshmalloowNo ratings yet

- Overview On Using Metadata To Manage Multimedia Data: January 1998Document27 pagesOverview On Using Metadata To Manage Multimedia Data: January 1998ruxandra28No ratings yet

- GLO1001 LXGB-GVBA (24 Dec 2020) #2Document8 pagesGLO1001 LXGB-GVBA (24 Dec 2020) #2edmarrodrigoNo ratings yet

- Monitoring DPD & Kol 29062021Document22 pagesMonitoring DPD & Kol 29062021Task ForceNo ratings yet

- The Chart Below Shows The Expenditure of Two Countries On Consumer Goods in 2010Document35 pagesThe Chart Below Shows The Expenditure of Two Countries On Consumer Goods in 2010Vy Lê100% (1)

- 1200 Sunwah PearlDocument121 pages1200 Sunwah PearlTram TungNo ratings yet

- Still With YouDocument8 pagesStill With YouCHLOE NG XIAN RU MoeNo ratings yet

- CH 1Document11 pagesCH 1Enas LotfyNo ratings yet

- South African Archaeological Society Goodwin SeriesDocument3 pagesSouth African Archaeological Society Goodwin SeriesGeoffrey BlundellNo ratings yet

- Interlinear 1 ChroniclesDocument259 pagesInterlinear 1 ChroniclesCarlos GutierrezNo ratings yet