Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Bargaining Over Berlin

Bargaining Over Berlin

Uploaded by

Ver Madrona Jr.Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Bargaining Over Berlin

Bargaining Over Berlin

Uploaded by

Ver Madrona Jr.Copyright:

Available Formats

Southern Political Science Association

Bargaining over Berlin: a Re-analysis of the First and Second Berlin Crises

Author(s): Stephen G. Walker

Source: The Journal of Politics, Vol. 44, No. 1 (Feb., 1982), pp. 152-164

Published by: Cambridge University Press on behalf of the Southern Political Science Association

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2130288 .

Accessed: 11/04/2014 20:55

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

.

Cambridge University Press and Southern Political Science Association are collaborating with JSTOR to

digitize, preserve and extend access to The Journal of Politics.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 202.57.58.233 on Fri, 11 Apr 2014 20:55:42 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Bargaining over Berlin:

a Re-analysis

of the First and Second

Berlin Crises

STEPHEN G. WALKER

IT HAS BEEN over thirty years since the 1948 Berlin Blockade, and

almost two decades have passed since the 1961 confrontation over

the Berlin Wall. Nevertheless, these relics of the Cold War remain

interesting as episodes of crisis bargaining. Soviet decision makers

initiated the blockade of Berlin in 1948 with two bargaining goals in

mind. Their maximum goal was to convince the other occupying

powers, France, the United Kingdom, and the United States, that

their recent decision to unify the three zones of occupation in West

Germany was unacceptable. In the event that the West German

reunification decision could not be reversed, the minimum Soviet

goal was to force the other three powers out of Berlin. A successful

Western airlift over the Soviet blockade of land and water routes to

Berlin ended in 1949 with a Russian agreement to remove the

blockade. This outcome was a diplomatic victory for the Western

allies, since both Soviet goals were thwarted.'

The second Berlin crisis followed a series of ultimatums from the

Soviet government over the last two years of the Eisenhower Ad-

ministration and culminated in the first year of the Kennedy Ad-

I

This sketch of the 1948 Berlin crisis is based upon two recent reviews of the

monographic literature dealing with the Berlin problem. See Glenn H. Snyder and

Paul.Diesing, Conflict Among Nations: Bargaining, Decision Making, and System

Structure in International Crises (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1977),

559-561; Alexander L. George and Richard Smoke, Deterrence in American Foreign

Policy: Theory and Practice (New York: Columbia University Press, 1974), 107-139.

This content downloaded from 202.57.58.233 on Fri, 11 Apr 2014 20:55:42 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

BARGAINING OVER BERLIN 153

ministration with the construction of the wall between East and

West Berlin. Unlike the 1948 crisis, when the maximum Soviet goal

was to prevent the formal division of Germany, this time the Rus-

sians wanted to make the division official. Their bargaining objec-

tives were to force the Western Powers out of Berlin and to gain

recognition that German reunification was no longer possible

without the mutual consent of the existing East and West German

governments. As tensions heightened between Washington and

Moscow, the Soviets also wanted to stop the emigration of refugees

from East Germany through Berlin into West Germany. The Allies

were not forced out of Berlin, but the successful establishment of the

Berlin Wall curbed the refugee flow and constituted a partial

diplomatic victory for the Eastern Bloc.2

Within each crisis the two sides selected a series of actions which

led to these outcomes. In this essay the goal is to analyze their

bargaining moves from a crisis management perspective and answer

some questions associated with this area of inquiry.

Models and Measures of Crisis Management

International crisis management is concerned with the identifica-

tion and analysis of strategies and tactics which will realize the goals

of the participants in a conflict situation and, at the same time,

avoid potentially undesirable consequences such as war or submis-

sion in the form of a military or diplomatic victory by the

opponent.3 In a recent review and appraisal of scholarly efforts to

understand international crises one analyst concludes, "A body of

[crisis management] propositions exists; it is unclear, however, how

much confidence one should place in this knowledge for use in crisis

management situations."4 In particular, there is ambiguity regard-

ing the most effective actions for eliciting a de-escalatory response

from the opponent. In Table 1 are four types of crisis bargaining

moves. The tactics which can be constructed from these moves vary

according to the direction (escalation or de-escalation) and the

2

Snyder and Diesing, ibid., 564-567; George and Smoke, ibid., 390-446.

3

Snyder and Diesing, ibid., 207. See also Alexander L. George, David K. Hall,

and William E. Simons, The Limits of Coercive Diplomacy (Boston: Little, Brown

and Company, 1971), 8-15; Raymond Tanter, "International Crisis Behavior: An Ap-

praisal of the Literature." Jerusalem Journal of International Relations, III (Winter-

Spring, 1978), 340-374.

4

Tanter, op. cit., 366.

This content downloaded from 202.57.58.233 on Fri, 11 Apr 2014 20:55:42 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

154 THE JOURNAL OF POLITICS, VOL. 44, 1982

resolve (the degree of motivation to stand firm) communicated by

their actions. A series of firm, unidirectional moves is sometimes

discredited as a bargaining tactic, because one variant (brinkman-

ship) courts war while the other (appeasement) risks domination.

Less risky tactics, such as coercive diplomacy and graduated-

reduction-in-international-tension

(G.R.I.T.), feature a flexible

series of escalatory and de-escalatory moves which attempt to com-

municate a resolve to negotiate and de-escalate only on a reciprocal

basis.5

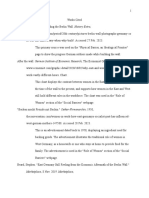

TABLE 1

A TYPOLOGY OF CRssis BARGAINING TACrICS

RESOLVE

Flexible Firm

Escalation Coercive

Escalation

Brinkmanship

DIRECTION

De-Escalation G.R.I.T. Appeasement

Crisis participants estimate each other's resolve from whatever in-

dicators are available, including one another's past and present

escalatory or de-escalatory moves." Corson has gathered such data

for the two Berlin crises.7 The Corson data are observations of

physical and verbal actions which vary along a conflict continuum

within and across the two crises. The characteristics of the Corson

data make it possible to rank the conflict intensity of each observa-

tion as more intense, less intense, or equally intense in comparison

with the other observations in the data set. Operationally, the

direction of an observation can be classified as an escalatory or a de-

5 George, Hall, and Simons, op. cit., and Charles Osgood, An Alternative to War

or Surrender (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1962).

6 Snyder and Diesing, op. cit., 254-256, who also identify the stakes and

capabilities of each participant as indicators of resolve; however, these indicators tend

to remain constant rather than vary within a crisis.

I

Walter Corson, "Conflict and Cooperation in East-West Relations: Measurement

and Explanation." (Prepared for the Sixty-sixth Annual Meeting of the American

Political Science Association in Los Angeles, CA, September 8-12, 1970.) The Corson

data for the two Berlin crises are reported in Raymond Tanter, Modelling and Manag-

ing International Conflicts: the Berlin Crises (Beverly Hills, CA: Sage, 1974).

This content downloaded from 202.57.58.233 on Fri, 11 Apr 2014 20:55:42 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

BARGAINING OVER BERLIN

155

escalatory move, depending upon whether its conflict intensity was

higher or lower than the actor's previous move.8

It is also possible to construct two measures of resolve with the

Corson data. The first is the degree of continuity in the series of

moves made by the actor who is initiating the present move. This

indicator is a measure of resolve which places the present move in

the context of the direction of the immediately preceding move by

the same actor. The two sequences of moves which communicate

flexible resolve are an escalation preceded by a de-escalation, and

vice versa. The sequences which indicate a firm resolve either to

escalate or de-escalate, respectively, are two escalations in a row

and two de-escalations in a row. The second measure of resolve is

the range of variety in an actor's present move, which may also com-

municate flexible or firm resolve. If actor A's move incorporates

only one type of action at one level of intensity prior to actor B's

response, or if A's combination of actions are all in the same direc-

tion prior to B's response, then the move communicates firm resolve.

However, if the variety of A's activities ranges in direction both

above and below the intensity of A's preceding move, then it signals

flexible resolve.9

In his analysis of Corson's data, Tanter identifies July 2, 1948 and

August 16, 1961 as the points which mark the peak intensity for each

Berlin crisis. On July 1, 1948, the U.S.S.R. formally withdrew

from the Berlin Command and by July 3rd had refused to lift their

blockade of traffic into Berlin until plans for a separate West Ger-

man government were dropped. On August 15, 1961, the Western

powers vigorously protested the Soviet border closure of August 13th

8

Corson, ibid., used the opinions of expert judges to place each observation on a

continuum, which contained numerical weights at selected intervals along its length.

These numerical values are irrelevant for simply ranking one observation as more or

less intense than another one.

9

When the variety of activities in a move ranges above and below the position of

the preceding move on the Corson scale, the numerical scale values for the move's

highest and lowest activities are combined with the numerical scale value of the

preceding move according to this formula: CNI

=

(HA

-

PM)

-

(PM

-

LA) + PM,

where CNI = the Composite Numerical Index of the scale value of the move in ques-

tion, HA = the numerical scale value of the move's Highest Activity, LA = the

numerical scale value of the move's Lowest Activity, and PM= the numerical scale

value of the Preceding Move by the same actor. This index ranks the move in question

by indicating the move's net change above or below the position of the actor's previous

move on the Corson scale. Approximately 20 percent of the 108 moves extrapolated

from Corson's Berlin data required the calculation of this index.

This content downloaded from 202.57.58.233 on Fri, 11 Apr 2014 20:55:42 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

156 THE JOURNAL OF POLITICS, VOL. 44, 1982

between East and West Berlin; by August 17th both sides had

deployed armed forces along the border.'0 In the following

analysis, the moves by East and West surrounding these crisis peaks

are extrapolated from the Corson data and classified according to

their escalatory or de-escalatory direction and their flexible or firm

resolve. "

This set of moves constitutes the bargaining interactions during a

very intense phase of each crisis, when crisis managers are par-

ticularly interested in identifying tactics which will elicit de-

escalatory responses. An analysis of the response patterns to dif-

ferent types and combinations of these moves during this phase of

the two crises may answer some important crisis management ques-

tions regarding the effective implementation of the tactics associated

with the bargaining moves in Table 1. Are escalatory or de-

escalatory tactics more likely to elicit a de-escalatory response? Are

the flexible tactics associated with G.R.I.T. and coercive diplomacy

more successful than the firm tactics characteristic of brinkmanship

or appeasement? Which is more closely associated with a de-

escalatory response, the sequence of moves or the range of activities

which constitute a move? What combinations of resolve and direc-

tion are the most effective bargaining tactics?

During the intense confrontation phase of an international con-

flict, it is plausible on theoretical grounds to assume that escalation

rather than de-escalation is the more likely response to any tactical

move. The confrontation itself is a product of the attempts by each

participant either to dominate or to resist domination. Under these

circumstances an escalatory move is likely to be countered with an

10

Tanter, op. cit., 88-91.

11

The observations for the 1948 crisis span the period between June 7, 1948 and

August 1, 1948, while the data for the 1961 crisis include observations between June

10, 1961 and September 12, 1961. Although the time frame is slightly longer for the

second crisis than for the first one, each ending date corresponds to the end of the in-

tense phase for each crisis (See Tanter, ibid., 84-85). The beginning dates mark the

occurrence of a dramatic event which precipitated a confrontation between East and

West. On June 7, 1948, the West announced the London Conference's recommenda-

tions for a separate West German state, and on June 4, 1961, the U.S.S.R. delivered

the latest six-month ultimatum regarding Berlin. The time frames for each crisis also

encompass approximately the same number of bargaining moves in the Corson data

set. There are no significant differences in the distribution of de-escalatory responses

among the moves before and after the dates identified by Tanter as the points of peak

intensity ( . 10; Yates corrected chi-square p > .05). Consequently, it is reasonable

to consider these moves as a set whose elements do not come from generically different

phases of the two conflicts.

This content downloaded from 202.57.58.233 on Fri, 11 Apr 2014 20:55:42 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

BARGAINING OVER BERLIN 157

escalatory response in order to avoid domination and demonstrate

resolve.'2 A de-escalatory move is also likely to be met with an

escalatory response in this context, if both sides prefer to dominate

rather than compromise. According to Snyder and Diesing, in both

Berlin crises each bloc leader ranked domination over the opponent

as a first preference and compromise as a second preference, because

these outcomes provided them with the two greatest payoffs. Each

one also wanted to avoid war and submission, because the payoffs

associated with these outcomes were less than the payoffs for

domination or compromise.'3

If this analysis of preference orderings by Snyder and Diesing is

correct, then the probability of a de-escalatory response to either

escalatory or de-escalatory tactics during the most intense phase of

each conflict is less than 50-50. Indeed, Tanter's (1974: 155-162)

previous analysis of the Corson data for the crisis phases of the two

Berlin conflicts shows no significant covariation between the actions

of one side and the responses of the other side. This absence of

covariation is consistent with the hypothesis that a de-escalatory

response is unlikely no matter what tactic is pursued. This point

has important implications for assessing the effectiveness of various

types or combinations of tactics.

Methodologically, it would appear that under these cir-

cumstances the normal social science definition of a "significant"

finding should be revised. Instead of defining the null hypothesis of

"no relationship" between tactic and response as an equiprobable

dichotomous distribution of escalatory and de-escalatory responses,

the null hypothesis for the expected frequency distribution should be

set at p < .50. At what level below p

=

.50 is determined by iden-

tifying the level below p

=

.50 where the liklihood of observing at

12

Snyder and Diesing, op. cit., 14, describe the confrontation phase of a crisis as

follows: "The collision of challenge and resistance produces a confrontation, which is

the core of the crisis . . . and is characterized by high or rising tension and predomi-

nately coercive tactics on both sides, each standing firm on its initial position and issu-

ing threats, warnings, military deployments, and other signals to indicate firmness, to

undermine the other's firmness, and generally to persuade the other that he must be

the one to back down if war is to be avoided." (Underlining is Snyder and Diesing's.)

13

Ibid., 92-93, 113-114, 268-275, 482. Snyder and Diesing argue that the motiva-

tions of both sides within each crisis were symmetrical, i.e., each one ranked the four

outcomes in the same order. However, they assert that the preference order for the

war and submission outcomes varied across the two crises. In the 1948 crisis each side

preferred submission (3rd) over war (4th), while in the 1961 crisis these preferences

were reversed.

This content downloaded from 202.57.58.233 on Fri, 11 Apr 2014 20:55:42 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

158 THE JOURNAL OF POLITICS, VOL. 44, 1982

least the actual frequency of de-escalatory responses by chance is c

.05. The closer the expected probability can be set to p = .50 and

still have the actual frequency of de-escalatory responses occurring

by chance be p

<

.05,

the more significant the association between

these responses and their tactical stimuli.'4

Consequently, the following analysis of crisis bargaining over

Berlin involves two steps. First, the frequency distributions of de-

escalatory and escalatory responses to various tactics are retrieved

and presented. Second, the frequency of de-escalatory responses to

each tactic is analyzed under different assumptions of expected

probability, ranging from p = .50 to p = .05.15 With this informa-

tion, it is possible to identify the most effective tactics. Even if the

odds are against any tactic eliciting a de-escalatory response, it is

still conceivable that the odds are worse for some tactics than for

others-which is important for crisis managers to know.

Bargaining over Berlin

The decision tree in Table 2 contains the distribution of responses

for the eight possible variants of de-escalatory tactics when both the

sequence and the range measures of resolve are taken into account.

The variety of appeasement tactics is low for the two Berlin crises.

The only one to appear frequently is the "pure" appeasement tactic

[H], in which both the sequence and the range communicate firm

de-escalatory resolve. This variant is also rather ineffective. The

null probability of a de-escalatory response would have to be as low

as (p

=

.20), in order to hypothesize that there is a statistically

significant (p c .05) relationship between this tactic and the actual

14 This reasoning resembles the argument advanced by some students of cluster bloc

analysis in computing indices of voting agreement and determining how strong the

agreement must be in order to be significant. Instead of selecting some arbitrary level

of strength, such as a voting agreement index value of .4 or .8, they argue that it is best

to select a high enough level of agreement so that the liklihood of gaining that level of

agreement by chance is quite low. See G. David Garson, Political Science Methods

(Boston: Holbrook Press, 1976), 211-213, and Peter Willetts, "Cluster Bloc Analysis

and Statistical Inference," American Political Science Review LXVI

(June, 1972),

569-582.

15 The probabilities are calculated from the binomial distribution according to the

formula which appears in Table 2. The logic of the binomial distribution and the

concept of probability are reviewed clearly and extensively in Hubert M. Blalock, Jr.,

Social Statistics (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1960), 97-134, and more succinctly in

Dickinson L. McCaw and George Watson, Political and Social Inquiry (New York:

John Wiley & Sons, 1976), 283-287.

This content downloaded from 202.57.58.233 on Fri, 11 Apr 2014 20:55:42 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

o

880 E

8o0 a 0 QO

E o

00 _ *i?

c! 0 0 0 e?

1 ?

-40

0i -vi1 - Ws

c If) ) C0 0I If) 0 0

ko to v

> o _ o e

El

o s

1 .o I [. C l;i ._~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~9

-

4;

2- * * * . * c* Cu Q

r- 00 ~ - d) ~C

- +~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~6.

~~~ C - ~ 0 C 1

C) CU oC> k

o

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~,0

I.~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~V

0 H

H

44~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~~~~>4

This content downloaded from 202.57.58.233 on Fri, 11 Apr 2014 20:55:42 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

160 THE JOURNAL OF POLITICS, VOL. 44, 1982

frequency of de-escalatory responses. By contrast, the G.R.I.T.

variants [A] and [C] are more effective in eliciting a de-escalatory

response. A greater proportion of de-escalatory responses is

associated with these tactics; the null probability of a de-escalatory

response can also be set closer to (p = .50) without rejecting the

hypothesis that there is a statistically significant (p < .05) relation-

ship between the responses and G.R.I.T. tactics [A] and [C].

The decision tree for escalatory tactics is in Table 3. A "pure"

brinkmanship tactic [H] is least effective; more effective brinkman-

ship variants are [F] and [G] in which the range of one move com-

municates flexibility. Coercive diplomacy tactics are most fre-

quent, and variant [D] is as effective as G.R.I.T.'s [A] tactic. The

null probability of a de-escalatory response can be set at (p = .30)

without rejecting the hypothesis that there is a statistically signifi-

cant (p < .05) relationship between the actual frequency of de-

escalatory responses and this type of coercive diplomacy tactics. A

comparison of Tables 2 and 3 indicates that flexible, controlled

pressure tactics are both the most frequent and most effective com-

binations of moves, while "pure" appeasement and brinkmanship

tactics are least frequent and least effective. Coercive diplomacy

tactics and the "semi-flexible" brinkmanship tactics [F] and [G] are

generally more effective controlled pressure tactics than the

G.R.I.T. variants except for G.R.I.T. tactic [A].

Conclusion

The generalizability of these findings to the analysis of other in-

ternational crises is limited by two sets of considerations. First,

their validity is subject to the constraints imposed by the small

number of observations and the small differences in effectiveness

among the various bargaining tactics. For five of the eight de-

escalatory tactical variants in Table 2, there are no more than two

observations per tactic. For most of the de-escalatory variants,

therefore, the evidence is simply insufficient to make an empirical

judgment about their effectiveness as tactics. Second, as Alexander

George has noted, the effectiveness of the more frequent coercive

diplomacy tactics depends ultimately upon the answers to three

questions. What response is expected of the opponent? How

strongly disinclined is the opponent toward this response? Which

specific tactics are likely to be most effective given the answers to the

This content downloaded from 202.57.58.233 on Fri, 11 Apr 2014 20:55:42 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

o0 0

'--

- I<

E no

*

, o

9 C 9

C) C)~~~~~~~C

c 0 0 0ll 0

3eq o o 0 0 0

Z m C Y) m

X

XO o

0 OC) " 0 0 o

o

mo c q

0 - 0 0

1-

fi

* eq

t= H L2 LE

O

8

3i cq 10 o m i~ 0 em eq 0

C)

0

C

L_ L.= I LmI

Q

R

*LnJ

Co~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~0

This content downloaded from 202.57.58.233 on Fri, 11 Apr 2014 20:55:42 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

162 THE JOURNAL OF POLITICS, VOL. 44, 1982

first two questions?"' This analysis of the Berlin crises has by no

means exhausted all of the implications associated with these ques-

tions.

Regarding the first question, George distinguishes between two

types of responses which may be expected from an opponent: "The

opponent may be asked to stop what he is doing; or he may be asked

to undo what he has been doing or to reverse what he has already ac-

complished.'7 He argues that this distinction among demands is

important, because the manipulative actions associated with coer-

cive diplomacy are likely to be more effective in achieving the first

type of demand. ". . . because it asks less of the opponent, the first

type of demand is easier to comply with and easier to enforce."',8 In

the 1948 crisis, the Western bloc succeeded in the demand that the

East stop their blockade of Berlin. However, the Soviets were un-

successful in reversing the Allied decision to unify West Germany. In

1961, the Soviet Union was effective in getting the United States to

mute (stop) its opposition to the establishment of the Berlin Wall,

whereas the United States was unable to tear down (undo) the Wall.

In neither crisis were the Russians able to force the Western Allies

out of Berlin. These outcomes are consistent with the limits of coer-

cive diplomacy and imply that it will be relatively ineffective in

other crises where the opponent is expected to undo or reverse what

has already been accomplished.

However, this conclusion is partly contingent on the answer to the

second question, viz., how disinclined is the opponent toward the

desired response? George hypothesizes that an opponent's

disinclination to yield is greater when the structure of the demand is

to undo what has been successfully accomplished rather than to stop

what is being attempted. He identifies this consideration plus

several other conditions which define how strongly the opponent is

disinclined toward a de-escalatory response.

"'

Most of these condi-

tions are not explicitly examined in this analysis of the Berlin crises.

Instead, they are presumed to be exogenous variables which con-

tribute to Snyder and Diesing's ranking of crisis outcomes for the

participants.20 The confrontation phase itself is also postulated as a

16

George, Hall, and Simons, op. cit., 22-23, 230-244.

17

Ibid., 22-23. George attributes these distinctions to Thomas Schelling, Arms

and Influence (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1966), 72, 77.

18

George, Hall, and Simons, ibid., 23.

19

Ibid., 23, 215-228.

20

From the perspective of the coercer, the eight conditions which affect a successful

This content downloaded from 202.57.58.233 on Fri, 11 Apr 2014 20:55:42 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

BARGAINING OVER BERLIN 163

condition which makes each participant disinclined (p < .50)

toward de-escalation and compliance with the demands of the other

side. Consequently, the generalizability of these findings may well

be limited to the confrontation phase of other crises with identically

ranked outcome preferences and structurally similar demands.

The answer to the third question regarding the relative effec-

tiveness of specific tactics, therefore, depends significantly upon the

conditions identified in the first two questions. Within the context

of these conditions George identifies two tactical variants of coercive

diplomacy, the try-and-see approach and the tacit-ultimatum ap-

proach, which he conceptualizes as located at the end points of a

continuum that appears to include both the coercive diplomacy and

the brinkmanship variants in Table 3.21 The continuum represents

the degree to which a given tactical move communicates the con-

tents of the classical diplomatic ultimatum: a specific demand on the

opponent; a time limit for compliance; a threat of punishment for

non-compliance that is sufficiently strong and credible.22 George's

analysis of the variables which form the contents of a move include

the variety of words and actions in the message and the mix of

positive inducements and negative sanctions that constitute the

move.23 It is these types of variables that are analyzed in Table 3

with the measures of direction and resolve for the moves in the

Berlin crises.

Tactic [A] in Table 3 is the weakest variant of coercive diplomacy,

while tactic [H] may extend beyond George's endpoint for strong

variants of coercive diplomacy. He argues that". . . coercive

diplomacy . . . [may] require genuine concessions to an opponent as

part of a quid pro quo that secures one's essential demands. Coer-

cive diplomacy, therefore, needs to be distinguished from pure coer-

cion; it includes the possibility of bargains, negotiations, and com-

promises.as well as coercive threats."24 The lack of any flexibility in

outcome for coercive diplomacy are (1) the strength of the coercer's motivation; (2) an

asymmetry of motivation favoring the coercer; (3) the clarity of the coercer's objec-

tives; (4) the sense of urgency to achieve the coercer's objectives; (5) the adequacy of

the coercer's domestic political support; (6) the coercer's usable military options; (7)

the opponent's fear of unacceptable escalation; (8) the clarity concerning the precise

terms of settlement. George, Hall, and Simons, 215-228. See also Snyder and Dies-

ing, op. cit., 479-480, 488-493, 510-514.

21

George, Hall, and Simons, ibid., 27.

22

Ibid., 27-28.

23

Ibid.,

25-30.

24 Ibid., 25.

This content downloaded from 202.57.58.233 on Fri, 11 Apr 2014 20:55:42 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

164 THE JOURNAL OF POLITICS, VOL. 44, 1982

the sequence or range of the moves for tactic [H] puts it at least on

the endpoint of George's coercive diplomacy continuum-and

beyond it if some positive inducement is a necessary characteristic of

even the strongest variant of coercive diplomacy. Tactic [A] falls

barely within the other endpoint of the continuum, because both the

sequence and the range of the moves for this escalatory tactic are

flexible.

The relative strength of each tactical variant, therefore, may be

compared by its mix of firm and flexible values for the sequence and

range measures. The most effective tactics in Table 3 are the flexi-

ble sequence/firm range combination [D] and the firm

sequence/semi-flexible range combination [G]. Although [D] and

[G] are intermediate variants between purely flexible (A) and purely

firm [H] escalatory tactics, they are strong tactics in comparison to

the other intermediate variants of escalatory moves. Both [D] and

[G] have "firm" values for two out of three measures. The other in-

termediate variants have only one "firm" value except for tactic [F],

which is the next most effective variant along with tactic [B]. The

last two variants share the common property of a firm value for the

range of the second move. The least effective intermediate variant,

[C], is also the weakest one in that it has only one firm property and

the range value of the second move is "flexible".

The relative success of "strong" rather than "weak" tactical

variants of coercive diplomacy in the two Berlin crises is consistent

with two features of these cases. First, strong tactics that stop just

short of pure coercion may be necessary during the confrontation

phase of a crisis, in order to overcome the tendency toward counter-

escalation that characterizes this phase of a crisis. Second, strong

tactics are more likely to be necessary when the motivation to resist

by the protagonists is symmetrical. The identical preference order-

ing for crisis outcomes, which Snyder and Diesing assign to both

sides in the Berlin crises, is consistent with the attribution of sym-

metrical motivations to East and West and with the relative effec-

tiveness of strong bargaining tactics during the two crises. Con-

versely, the relative effectiveness of strong coercive diplomacy tac-

tics for these crises is not likely to be generalizable to other interna-

tional crises with asymmetrical motivational structures.

This content downloaded from 202.57.58.233 on Fri, 11 Apr 2014 20:55:42 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

You might also like

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (842)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5807)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1091)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (346)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- E-CAT35TR003 TRO 3145 Kurita - Draconis CombineDocument114 pagesE-CAT35TR003 TRO 3145 Kurita - Draconis CombineTaekyongKim80% (5)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- A Primer in The Art of Deception.Document795 pagesA Primer in The Art of Deception.pzimmer3No ratings yet

- The Last Caravan Quickstart v3Document20 pagesThe Last Caravan Quickstart v3lolo loloNo ratings yet

- Savage Worlds - Weird Wars - Weird War I - Adv - in Vino VeritasDocument15 pagesSavage Worlds - Weird Wars - Weird War I - Adv - in Vino Veritasgercog95100% (1)

- Obama Foreign PolicyDocument11 pagesObama Foreign PolicyVer Madrona Jr.No ratings yet

- EDCADocument24 pagesEDCAfreah genice tolosaNo ratings yet

- Xcom Enemy Within 2013 Tech Tree Flow ChartDocument1 pageXcom Enemy Within 2013 Tech Tree Flow ChartBenNo ratings yet

- Command 002 - Erich Von Manstein PDFDocument68 pagesCommand 002 - Erich Von Manstein PDFPantelis Chouridis100% (7)

- Bayonets 1Document4 pagesBayonets 1Flavio PereiraNo ratings yet

- Faction Fiefdoms of GondorDocument1 pageFaction Fiefdoms of GondorStormJaegerNo ratings yet

- Foreign Policy As Social Construction: A Post-Positivist Analysis of U.S. Counterinsurgency Policy in The PhilippinesDocument25 pagesForeign Policy As Social Construction: A Post-Positivist Analysis of U.S. Counterinsurgency Policy in The PhilippinesVer Madrona Jr.No ratings yet

- Boserup, Development TheoryDocument12 pagesBoserup, Development TheoryVer Madrona Jr.No ratings yet

- Bot in AsiaDocument42 pagesBot in AsiaVer Madrona Jr.No ratings yet

- Gibbons and Katz, Layoffs and Lemons PDFDocument31 pagesGibbons and Katz, Layoffs and Lemons PDFVer Madrona Jr.No ratings yet

- Hettne, Development of Development TheoryDocument21 pagesHettne, Development of Development TheoryVer Madrona Jr.No ratings yet

- Ecologism and The Politics of Sensibilities: Andrew HeywoodDocument6 pagesEcologism and The Politics of Sensibilities: Andrew HeywoodVer Madrona Jr.No ratings yet

- Democracy Tradition Us Foreign Policy PDFDocument22 pagesDemocracy Tradition Us Foreign Policy PDFVer Madrona Jr.No ratings yet

- Explaining Us Strategic Partnership PDFDocument29 pagesExplaining Us Strategic Partnership PDFVer Madrona Jr.No ratings yet

- Playing PartnersDocument27 pagesPlaying PartnersVer Madrona Jr.No ratings yet

- Ra 7797Document2 pagesRa 7797Ver Madrona Jr.No ratings yet

- Central European Monarchs ClashDocument5 pagesCentral European Monarchs ClashxKingR2L2No ratings yet

- Breaking Gods - An African Postcolonial Gothic Reading of Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie's 'Purple Hibiscus' and 'Half of A Yellow Sun'Document21 pagesBreaking Gods - An African Postcolonial Gothic Reading of Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie's 'Purple Hibiscus' and 'Half of A Yellow Sun'Rhudene BarnardNo ratings yet

- 00 Guardian VaultsDocument276 pages00 Guardian VaultsJohn CannonNo ratings yet

- The Story So Far...Document4 pagesThe Story So Far...Luke PoonNo ratings yet

- The Search For Identity - American Prose Writers - 1970 To PresentDocument51 pagesThe Search For Identity - American Prose Writers - 1970 To PresentPauline MendozaNo ratings yet

- Line 1 Line 2 Line 3: 9 Liner Medevac RequestDocument1 pageLine 1 Line 2 Line 3: 9 Liner Medevac Requestjack.cullinan2046100% (1)

- 1996 Diaz-Andreu & ChampionDocument22 pages1996 Diaz-Andreu & ChampionMuris ŠetkićNo ratings yet

- C.E. Callwell, The Roots of Counter-Insurgency, and The Nineteenth Century Context PDFDocument18 pagesC.E. Callwell, The Roots of Counter-Insurgency, and The Nineteenth Century Context PDFStefanNo ratings yet

- Monomyth QuestionsDocument13 pagesMonomyth Questionsapi-262774252No ratings yet

- 20-Sep-Sv 44 PaxDocument2 pages20-Sep-Sv 44 PaxRafiz Sadia TravelsNo ratings yet

- The Sniper Powerpoint PresentationDocument17 pagesThe Sniper Powerpoint PresentationNoviachri Sa'diyahNo ratings yet

- Urbanization and Modernization of ManilaDocument11 pagesUrbanization and Modernization of ManilaEj Bañares100% (1)

- Sources For Berlin Wall Final Sources 1Document24 pagesSources For Berlin Wall Final Sources 1api-675717805No ratings yet

- Daftar PTK Smks Muhammadiyah Bungoro 2015-05-24 11-10-31Document63 pagesDaftar PTK Smks Muhammadiyah Bungoro 2015-05-24 11-10-31Junadi Akmal MNo ratings yet

- TransitionDocument338 pagesTransitionΓιάννης ΜανιταράςNo ratings yet

- Zaid Hamid: Corona Virus & The Coming of "Messiah" - English VersionDocument7 pagesZaid Hamid: Corona Virus & The Coming of "Messiah" - English VersionMahwish HamidNo ratings yet

- Altamirano's Demons. Constructing Martín Sanchez in El ZarcoDocument16 pagesAltamirano's Demons. Constructing Martín Sanchez in El Zarcojesusdavid5781No ratings yet

- Banaras Hindu University,: Faculty of LawDocument4 pagesBanaras Hindu University,: Faculty of LawShivangi SinghNo ratings yet

- Annotated BibliographyDocument13 pagesAnnotated BibliographyJoshuaNo ratings yet

- Volume 1Document261 pagesVolume 1John Caezar YatarNo ratings yet

- Oppenheimer The Secrets He Protected and The Suspicions That Followed HimDocument6 pagesOppenheimer The Secrets He Protected and The Suspicions That Followed HimEwa AnthoniukNo ratings yet