Professional Documents

Culture Documents

What Is Enlightment by Immanuel Kant

Uploaded by

Gabriela Pelozone LimaOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

What Is Enlightment by Immanuel Kant

Uploaded by

Gabriela Pelozone LimaCopyright:

Available Formats

An Answer to the Question: "What is Enlightenment?

"

IMMANUEL KANT

Konigsberg in Prussia, 30th September, 1784.

Enlightenment is man's emergence from his selfincurre! immaturit". #mmaturit" is the

inabilit" to use one's o$n un!erstan!ing $ithout the gui!ance of another. %his

immaturit" is selfincurre! if its cause is not lac& of un!erstan!ing, but lac& of

resolution an! courage to use it $ithout the gui!ance of another. %he motto of

enlightenment is therefore' Sapere au!e( )a*e courage to use "our o$n un!erstan!ing(

+a,iness an! co$ar!ice are the reasons $h" such a large proportion of men, e*en $hen

nature has long emancipate! them from alien gui!ance -naturaliter maiorennes.,

ne*ertheless gla!l" remain immature for life. /or the same reasons, it is all too eas" for

others to set themsel*es up as their guar!ians. #t is so con*enient to be immature( #f #

ha*e a boo& to ha*e un!erstan!ing in place of me, a spiritual a!*iser to ha*e a

conscience for me, a !octor to 0u!ge m" !iet for me, an! so on, # nee! not ma&e an"

efforts at all. # nee! not thin&, so long as # can pa"1 others $ill soon enough ta&e the

tiresome 0ob o*er for me. %he guar!ians $ho ha*e &in!l" ta&en upon themsel*es the

$or& of super*ision $ill soon see to it that b" far the largest part of man&in! -inclu!ing

the entire fair se2. shoul! consi!er the step for$ar! to maturit" not onl" as !ifficult but

also as highl" !angerous. )a*ing first infatuate! their !omesticate! animals, an!

carefull" pre*ente! the !ocile creatures from !aring to ta&e a single step $ithout the

lea!ingstrings to $hich the" are tie!, the" ne2t sho$ them the !anger $hich threatens

them if the" tr" to $al& unai!e!. 3o$ this !anger is not in fact so *er" great, for the"

$oul! certainl" learn to $al& e*entuall" after a fe$ falls. 4ut an e2ample of this &in! is

intimi!ating, an! usuall" frightens them off from further attempts.

%hus it is !ifficult for each separate in!i*i!ual to $or& his $a" out of the immaturit"

$hich has become almost secon! nature to him. )e has e*en gro$n fon! of it an! is

reall" incapable for the time being of using his o$n un!erstan!ing, because he $as

ne*er allo$e! to ma&e the attempt. 5ogmas an! formulas, those mechanical

instruments for rational use -or rather misuse. of his natural en!o$ments, are the ball

an! chain of his permanent immaturit". 6n! if an"one !i! thro$ them off, he $oul!

still be uncertain about 0umping o*er e*en the narro$est of trenches, for he $oul! be

unaccustome! to free mo*ement of this &in!. %hus onl" a fe$, b" culti*ating the1r o$n

min!s, ha*e succee!e! in freeing themsel*es from immaturit" an! in continuing bol!l"

on their $a".

%here is more chance of an entire public enlightening itself. %his is in!ee! almost

ine*itable, if onl" the public concerne! is left in free!om. /or there $ill al$a"s be a fe$

$ho thin& for themsel*es, e*en among those appointe! as guar!ians of the common

mass. Such guar!ians, once the" ha*e themsel*es thro$n off the "o&e of immaturit",

$ill !isseminate the spirit of rational respect for personal *alue an! for the !ut" of all

men to thin& for themsel*es. %he remar&able thing about this is that if the public, $hich

$as pre*iousl" put un!er this "o&e b" the guar!ians, is suitabl" stirre! up b" some of

the latter $ho are incapable of enlightenment, it ma" subse7uentl" compel the guar!ians

themsel*es to remain un!er the "o&e. /or it is *er" harmful to propagate pre0u!ices,

because the" finall" a*enge themsel*es on the *er" people $ho first encourage! them

-or $hose pre!ecessors !i! so.. %hus a public can onl" achie*e enlightenment slo$l". 6

re*olution ma" $ell put an en! to autocratic !espotism an! to rapacious or po$er

see&ing oppression, but it $ill ne*er pro!uce a true reform in $a"s of thin&ing. #nstea!,

ne$ pre0u!ices, li&e the ones the" replace!, $ill ser*e as a leash to control the great

unthin&ing mass.

/or enlightenment of this &in!, all that is nee!e! is free!om. 6n! the free!om in

7uestion is the most innocuous form of all8free!om to ma&e public use of one's reason

in all matters. 4ut # hear on all si!es the cr"' 5on't argue( %he officer sa"s' 5on't argue,

get on para!e( %he ta2official' 5on't argue, pa"( %he clerg"man' 5on't argue, belie*e(

-9nl" one ruler in the $orl! sa"s' 6rgue as much as "ou li&e an! about $hate*er "ou

li&e, but obe"(.. . 6ll this means restrictions on free!om e*er"$here. 4ut $hich sort of

restriction pre*ents enlightenment, an! $hich, instea! of hin!ering it, can actuall"

promote it : # repl"' %he public use of man's reason must al$a"s be free, an! it alone

can bring about enlightenment among men1 the pri*ate use of reason ma" 7uite often be

*er" narro$l" restricte!, ho$e*er, $ithout un!ue hin!rance to the progress of

enlightenment. 4ut b" the public use of one's o$n reason # mean that use $hich an"one

ma" ma&e of it as a man of learning a!!ressing the entire rea!ing public. ;hat # term

the pri*ate use of reason is that $hich a person ma" ma&e of it in a particular ci*il post

or office $ith $hich he is entruste!.

3o$ in some affairs $hich affect the interests of the common$ealth, $e re7uire a

certain mechanism $hereb" some members of the common$ealth must beha*e purel"

passi*el", so that the" ma", b" an artificial common agreement, be emplo"e! b" the

go*ernment for public en!s -or at least !eterre! from *itiating them.. #t is, of

course,impermissible to argue in such cases1 obe!ience is imperati*e. 4ut in so far as

this or that in!i*i!ual $ho acts as part of the machine also consi!ers himself as a

member of a complete common$ealth or e*en of cosmopolitan societ", an! thence as a

man of learning $ho ma" through his $ritings a!!ress a public in the truest sense of the

$or!, he ma" 'in!ee! argue $ithout harming the affairs in $hich he is emplo"e! for

some of the time in a passi*e capacit". %hus it $oul! be *er" harmful if an officer

recei*ing an or!er from his superiors $ere to 7uibble openl", $hile on !ut", about the

appropriateness or usefulness of the or!er in 7uestion. )e must simpl" obe". 4ut he

cannot reasonabl" be banne! from ma&ing obser*ations as a man of learning on the

errors in the militar" ser*ice, an! from submitting these to his public for 0u!gement.

%he citi,en cannot refuse to pa" the ta2es impose! upon him1 presumptuous criticisms

of such ta2es, $here someone is calle! upon to pa" them, ma" be punishe! as an

outrage $hich coul! lea! to general insubor!ination. 3onetheless, the same citi,en !oes

not contra*ene his ci*il obligations if, as a learne! in!i*i!ual, he publicl" *oices his

thoughts on the impropriet" or e*en in0ustice of such fiscal measures. #n the same $a",

a clerg"man is boun! to instruct his pupils an! his congregation in accor!ance $ith the

!octrines of the church he ser*es, for he $as emplo"e! b" it on that con!ition. 4ut as a

scholar, he is completel" free as $ell as oblige! to impart to the public all his carefull"

consi!ere!, $ellintentione! thoughts on the mista&en aspects of those !octrines, an! to

offer suggestions for a better arrangement of religious an! ecclesiastical affairs. 6n!

there is nothing in this $hich nee! trouble the conscience. #1or $hat he teaches in

pursuit of his !uties as an acti*e ser*ant of the church is presente! b" him as something

$hich he is not empo$ere! to teach at his o$n !iscretion, but $hich he is emplo"e! to

e2poun! in a prescribe! manner an! in someone else's name. )e $ill sa"' 9ur church

teaches this or that, an! these are the arguments it uses. )e then e2tracts as much

practical *alue as possible for his congregation from precepts to $hich he $oul! not

himself subscribe $ith full con*iction, but $hich he can ne*ertheless un!erta&e to

e2poun!, since it is not in fact $holl" impossible that the" ma" contain truth. 6t all

e*ents, nothing oppose! to the essence of religion is present in such !octrines. /or if the

clerg"man thought he coul! fin! an"thing of this sort in them, he $oul! not be able to

carr" out his official !uties in goo! conscience, an! $oul! ha*e to resign. %hus the use

$hich someone emplo"e! as a teacher ma&es of his reason in the presence of his

congregation is purel" pri*ate, since a congregation, ho$e*er large it is, is ne*er an"

more than a !omestic gathering. #n *ie$ of this, he is not an! cannot be free as a priest,

sin< he is acting on a commission impose! from outsi!e. =on*ersel", as a scholar

a!!ressing the real public -i.e. the $orl! at large. through his $ritings, the clerg"man

ma&ing public use of his reason en0o"s unlimite! free!om to use his o$n reason an! to

spea& in his o$n person. /or to maintain that the guar!ians of the people in spiritual

matters shoul! themsel*es be immature, is an absur!it" $hich amounts to ma&ing

absur!ities permanent.

4ut shoul! not a societ" of clerg"men, for e2ample an ecclesiastical s"no! or a

*enerable presb"ter" -as the 5utch call it., be entitle! to commit itself b" oath to a

certain unalterable set of !octrines, in or!er to secure for all time a constant

guar!ianship o*er each of its members, an! through them o*er the people : # repl" that

this is 7uite impossible. 6 contract of this &in!,conclu!e! $ith a *ie$ to pre*enting all

further enlightenment of man&in! for e*er, is absolutel" null an! *oi!, e*en if it is

ratifie! b" the supreme po$er, b" #mperial 5iets an! the most solemn peace treaties.

9ne age cannot enter into an alliance on oath to put the ne2t age in a position $here it

$oul! be impossible for it to e2ten! an! correct its &no$le!ge, particularl" on such

important matters, or to ma&e an" progress $hatsoe*er in enlightenment. %his $oul! be

a crime against human nature, $hose original !estin" lies precisel" in such progress.

+ater generations are thus perfectl" entitle! to !ismiss these agreements as unauthorise!

an! criminal. %o test $hether an" particular measure can be agree! upon as a la$ for a

people, $e nee! onl" as& $hether a people coul! $ell impose such a la$ upon itself.

%his might $ell be possible for a specifie! short perio! as a means of intro!ucing a

certain or!er, pen!ing, as it $ere, a better solution. %his $oul! also mean that each

citi,en, particularl" the clerg"man, $oul! be gi*en a free han! as a scholar to comment

publicl", i.e. in his $ritings, on the ina!e7uacies of current institutions. >ean$hile, the

ne$l" establishe! or!er $oul! continue to e2ist, until public insight into the nature of

such matters ha! progresse! an! pro*e! itself to the point $here, b" general consent -if

not unanimousl"., a proposal coul! be submitte! to the cro$n. %his $oul! see& to

protect the congregations $ho ha!, for instance, agree! to alter their religious

establishment in accor!ance $ith their o$n notions of $hat higher insight is, but it

$oul! not tr" to obstruct those $ho $ante! to let things remain as before. 4ut it is

absolutel" impermissible to agree, e*en for a single lifetime, to a permanent religious

constitution $hich noone might publicl" 7uestion. /or this $oul! *irtuall" nullif" a

phase in man's up$ar! progress, thus ma&ing it fruitless an! e*en !etrimental to

subse7uent generations. 6 man ma" for his o$n person, an! e*en then onl" for a

limite! perio!, postpone enlightening himself in matters he ought to &no$ about. 4ut to

renounce such enlightenment completel", $hether for his o$n person or e*en more so

for later generations, means *iolating an! trampling un!erfoot the sacre! rights of

man&in!. 4ut something $hich a people ma" not e*en impose upon itself can still less

be impose! upon it b" a monarch1 for his legislati*e authorit" !epen!s precisel" upon

his uniting the collecti*e $ill of the people in his o$n. So long as he sees to it that all

true or imagine! impro*ements are compatible $ith the ci*il or!er, he can other$ise

lea*e his sub0ects to !o $hate*er the" fin! necessar" for their sal*ation, $hich is none

of his business. 4ut it is his business to stop an"one forcibl" hin!ering others from

$or&ing as best the" can to !efine an! promote their sal*ation. #t in!ee! !etracts from

his ma0est" if he interferes in these affairs b" sub0ecting the $ritings in $hich his

sub0ects attempt to clarif" their religious i!eas to go*ernmental super*ision. %his

applies if he !oes so acting upon his o$n e2alte! opinions8 in $hich case he e2poses

himself to the reproach' =aesar non est supra ?rammaticos8but much more so if he

!emeans his high authorit" so far as to support the spiritual !espotism of a fe$ t"rants

$ithin his state against the rest of his sub0ects.

#f it is no$ as&e! $hether $e at present li*e in an enlightene! age, the ans$er is' 3o,

but $e !o li*e in an age of enlightenment. 6s things are at present, $e still ha*e a long

$a" to go before men as a $hole can be in a position -or can e*er be put into a position.

of using their o$n un!erstan!ing confi!entl" an! $ell in religious matters, $ithout

outsi!e gui!ance. 4ut $e !o ha*e !istinct in!ications that the $a" is no$ being cleare!

for them to $or& freel" in this !irection, an! that the obstacles to uni*ersal

enlightenment, to man's emergence from his selfincurre! immaturit", are gra!uall"

becoming fe$er. #n this respect our age is the age of enlightenment, the centur" of

/re!eric&.

6 prince $ho !oes not regar! it as beneath him to sa" that he consi!ers it his !ut", in

religious matters, not to prescribe an"thing to his people, but to allo$ them complete

free!om, a prince $ho thus e*en !eclines to accept the presumptuous title of tolerant, is

himself enlightene!. )e !eser*es to be praise! b" a grateful present an! posterit" as the

man $ho first liberate! man&in! from immaturit" -as far as go*ernment is concerne!.,

an! $ho left all men free to use their o$n reason in all matters of conscience. @n!er his

rule, ecclesiastical !ignitaries, not$ithstan!ing their official !uties, ma" in their

capacit" as scholars freel" an! publicl" submit to the 0u!gement of the $orl! their

*er!icts an! opinions, e*en if these !e*iate here #n! there from ortho!o2 !octrine. %his

applies e*en more to all others $ho are not restricte! b" an" official !uties. %his spirit

of free!om is also sprea!ing abroa!, e*en $here it has to struggle $ith out$ar!

obstacles impose! b" go*ernments $hich misun!erstan! their o$n function. /or such

go*ernments an no$ $itness a shining e2ample of ho$ free!om ma" e2ist $ithout in

the least 0eopar!ising public concor! an! the unit" of the common$ealth. >en $ill of

their o$n accor! gra!uall" $or& their $a" out of barbarism so long as artificial

measures are not !eliberatel" a!opte! to &eep them in it.

# ha*e portra"e! matters of religion as the focal point of enlightenment, i.e. of man's

emergence from his selfincurre! immaturit". %his is firstl" because our rulers ha*e no

interest in assuming the role of guar!ians o*er their sub0ects so fir as the arts an!

sciences are concerne!, an! secon!l", because religious immaturit" is the most

pernicious an! !ishonourable *ariet" of all. 4ut the attitu!e of min! of a hea! of state

$ho fa*ours free!om in the arts an! sciences e2ten!s e*en further, for he realises that

there is no !anger e*en to his legislation if he allo$s his sub0ects to ma&e public use of

their o$n reason an! to put before the public their thoughts on better $a"s of !ra$ing

up la$s, e*en if this entails forthright criticism of the current legislation. ;e ha*e

before us a brilliant e2ample of this &in!, in $hich no monarch has "et surpasse! the

one to $hom $e no$ pa" tribute.

4ut onl" a ruler $ho is himself enlightene! an! has no far of phantoms, "et $ho

li&e$ise has at han! a $ell!iscipline! an! numerous arm" to guarantee public securit",

ma" sa" $hat no republic $oul! !are to sa"' 6rgue as much as "ou li&e an! about

$hate*er "ou li&e, but obe"( %his re*eals to us a strange an! une2pecte! pattern in

human affairs -such as $e shall al$a"s fin! if $e consi!er them in the $i!est sense, in

$hich nearl" e*er"thing is para!o2ical.. 6 high !egree of ci*il free!om seems

a!*antageous to a people's intellectual free!om, "et it also sets up insuperable barriers

to it. =on*ersel", a lesser !egree of ci*il free!om gi*es intellectual free!om enough

room to e2pan! to its fullest e2tent. %hus once the germ on $hich nature has la*ishe!

most care8man's inclination an! *ocation to thin& freel"8has !e*elope! $ithin this

har! shell, it gra!uall" reacts upon the mentalit" of the people, $ho thus gra!uall"

become increasingl" able to act freel" E*entuall", it e*en influences the principles of

go*ernments, $hich fin! that the" can themsel*es profit b" treating man, $ho is more

than a machine, in a manner appropriate to his !ignit".

%he En!.

;orl! Public +ibrar" an! Pro0ect ?utenberg =onsortia =enter,

bringing the $orl!'s e4oo& =ollections together.

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- World History Patterns of Interaction Glossary PDFDocument16 pagesWorld History Patterns of Interaction Glossary PDFUsha Stanyer40% (5)

- The Age of IdeologyDocument217 pagesThe Age of IdeologyAhmed Laheeb100% (1)

- Condon, Ed - Heresy by AssociationDocument287 pagesCondon, Ed - Heresy by AssociationCristian KameniczkiNo ratings yet

- Enlightenment Cosmopolitanism by David AdamsDocument185 pagesEnlightenment Cosmopolitanism by David AdamsSantiago Navajas100% (1)

- 1 Merged PDFDocument296 pages1 Merged PDFJosé Luis Cervantes CortésNo ratings yet

- JPAL EdTech ReviewDocument102 pagesJPAL EdTech ReviewGabriela Pelozone LimaNo ratings yet

- Education, Globalisation and The Voice of Knowledge (Young) PDFDocument29 pagesEducation, Globalisation and The Voice of Knowledge (Young) PDFGabriela Pelozone LimaNo ratings yet

- Hierarchical Clustering and Topology For Psychometric ValidationDocument16 pagesHierarchical Clustering and Topology For Psychometric ValidationGabriela Pelozone LimaNo ratings yet

- Mckinsey LA - Drivers of Student PerformanceDocument72 pagesMckinsey LA - Drivers of Student PerformanceArturo Herrera CarvajalNo ratings yet

- Bourdieu, Pierre - On TelevisionDocument53 pagesBourdieu, Pierre - On TelevisionGedo LaviniaNo ratings yet

- Azocar 2001Document11 pagesAzocar 2001Gabriela Pelozone LimaNo ratings yet

- Armstrong Nancy Fiction of BourgeoisMoralityDocument21 pagesArmstrong Nancy Fiction of BourgeoisMoralityGabriela Pelozone LimaNo ratings yet

- Mckinsey LA - Drivers of Student PerformanceDocument72 pagesMckinsey LA - Drivers of Student PerformanceArturo Herrera CarvajalNo ratings yet

- Unit Presentation: Encouraging Gender EqualityDocument14 pagesUnit Presentation: Encouraging Gender EqualitySonia toledanoNo ratings yet

- GGDocument5 pagesGGfsdfsfsdfdsfsdsNo ratings yet

- (Suny Series in the Thought and Legacy of Leo Strauss) Corine Pelluchon, Robert Howse - Leo Strauss and the Crisis of Rationalism_ Another Reason, Another Enlightenment-State University of New York PrDocument324 pages(Suny Series in the Thought and Legacy of Leo Strauss) Corine Pelluchon, Robert Howse - Leo Strauss and the Crisis of Rationalism_ Another Reason, Another Enlightenment-State University of New York PrLorena García100% (1)

- CAT 2019 Question Paper (Slot 2) by CrackuDocument101 pagesCAT 2019 Question Paper (Slot 2) by CrackuKritika GargNo ratings yet

- European History Practice Test I-1Document20 pagesEuropean History Practice Test I-1Pedro Rodriguez Jr.No ratings yet

- 02 Enlightenment & The Intellectual Foundations of Modern CultureDocument414 pages02 Enlightenment & The Intellectual Foundations of Modern Cultureerdem102100% (3)

- J. G. A. Pocock - Barbarism and Religion, Vol 1 The Enlightenments of Edward Gibbon Cambridge University Press (1999) PDFDocument356 pagesJ. G. A. Pocock - Barbarism and Religion, Vol 1 The Enlightenments of Edward Gibbon Cambridge University Press (1999) PDFrfsgaspar5372100% (1)

- What Is Philosophy of Technology?Document172 pagesWhat Is Philosophy of Technology?hemicefaloNo ratings yet

- American Literature - NotesDocument11 pagesAmerican Literature - NotesЈана ПашовскаNo ratings yet

- About The Hegelian Ticklish SubjectDocument5 pagesAbout The Hegelian Ticklish SubjectRobbert Adrianus VeenNo ratings yet

- Where Is God When You Cannot Find Him in Church.Document550 pagesWhere Is God When You Cannot Find Him in Church.Jim JohnsonNo ratings yet

- Factors That Contributed To The Rise and Development of SociologyDocument3 pagesFactors That Contributed To The Rise and Development of SociologysylvesterNo ratings yet

- Colin Jenkins Juxtaposing AnarchyDocument13 pagesColin Jenkins Juxtaposing AnarchyJesus LimaNo ratings yet

- Learning Module For Senior High School: Subject: Discipline and Ideas in The Social SciencesDocument23 pagesLearning Module For Senior High School: Subject: Discipline and Ideas in The Social SciencesWET WATERNo ratings yet

- American Revolution - Enlightenment - Arrival of Columbus To America - French RevolutionDocument12 pagesAmerican Revolution - Enlightenment - Arrival of Columbus To America - French RevolutionAlejandra GuarinNo ratings yet

- NRT Annual Report 1992-1993Document40 pagesNRT Annual Report 1992-1993National Round Table on the Environment and the EconomyNo ratings yet

- Pioneers in Criminology Edward LivingstonDocument9 pagesPioneers in Criminology Edward LivingstonPASION Jovelyn M.No ratings yet

- Magic CodexDocument588 pagesMagic CodexDan SerranoNo ratings yet

- Blessings in DisguiseDocument238 pagesBlessings in DisguiseAJ HassanNo ratings yet

- The Vatican Manuscript of Spinozas Ethic PDFDocument6 pagesThe Vatican Manuscript of Spinozas Ethic PDFJoaquín Bahamondes AzócarNo ratings yet

- At The Origins of Music AnalysisDocument228 pagesAt The Origins of Music Analysismmmahod100% (1)

- The Ancien Régime and the EnlightenmentDocument38 pagesThe Ancien Régime and the EnlightenmentError_017No ratings yet

- Technocracy Reloaded Preview Manuscript 1Document55 pagesTechnocracy Reloaded Preview Manuscript 1KiffNo ratings yet

- History NotesDocument8 pagesHistory NotesSonia Regina Florián CéspedesNo ratings yet

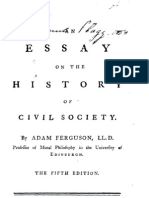

- An Essay On The History of Civil Society (1767) - Adam Ferguson FacsDocument476 pagesAn Essay On The History of Civil Society (1767) - Adam Ferguson Facsdp1974100% (1)