Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Memory Training As A Prerequisit of Identity Building Following Brain Injury

Uploaded by

JodiMBrown0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

19 views1 pageMemory Training as a Prerequisite of Identity Rebuilding following brain injury mia foxhall and birgit gurr. Jr's memory improved: he could locate places on the map, and remember routes around the hospital ward. Despite accuracy in route finding and recall, he could not consistently construct a mental map of the ward and link it to reality. Seven sessions of errorless, face-name learning trials were administered, spread across 14 days.

Original Description:

Original Title

Memory Training as a Prerequisit of Identity Building Following Brain Injury

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentMemory Training as a Prerequisite of Identity Rebuilding following brain injury mia foxhall and birgit gurr. Jr's memory improved: he could locate places on the map, and remember routes around the hospital ward. Despite accuracy in route finding and recall, he could not consistently construct a mental map of the ward and link it to reality. Seven sessions of errorless, face-name learning trials were administered, spread across 14 days.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

19 views1 pageMemory Training As A Prerequisit of Identity Building Following Brain Injury

Uploaded by

JodiMBrownMemory Training as a Prerequisite of Identity Rebuilding following brain injury mia foxhall and birgit gurr. Jr's memory improved: he could locate places on the map, and remember routes around the hospital ward. Despite accuracy in route finding and recall, he could not consistently construct a mental map of the ward and link it to reality. Seven sessions of errorless, face-name learning trials were administered, spread across 14 days.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 1

Memory Training as a Prerequisite of Identity Rebuilding

following Brain Injury

Mia Foxhall and Birgit Gurr

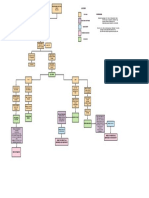

Procedure

Background

Intervention 1: Errorless Face - Name Learning

Intervention 2: Orientation and Map - Learning

Intervention 3: Cognitive Music Therapy to aid Identity Rebuilding

JRs memory improved: he could independently locate places on the map,

and remember routes around the hospital ward.

Despite accuracy in route finding and recall, JR could not consistently

construct a mental map of the ward and link it to reality.

Procedure 2b

Outcome

Patient Information

To optimise orientation and improve learning ability, seven sessions of

errorless, face-name learning trials were administered, spread across 14 days.

JR was presented with four staff photos and trained to match photos to staff

name and occupation. Trials were repeated three times within each session.

Delayed recall was tested after 15 minutes. The interval period was spent

completing basic sustained attention tasks.

JR scored one point for each correct name and occupation.

Outcome

JRs score improved from 22.5 to 30 with training, suggesting an improvement

in memory.

This success transferred to independently recognising staff in day-to-day

interactions on the ward.

JR experienced a sense of achievement and felt more confident working with

ward staff.

20

22

24

26

28

30

32

T1 T2 T3 T4 T5 T6 T7

M

e

m

o

r

y

R

e

c

a

l

l

S

c

o

r

e

Sessions

Patient JR continued to present with confusion regarding the ward environment

e.g. he believed that he had several other rooms on different wards.

JR participated in six sessions of errorless, map-learning trials across 12 days.

He was shown photos of important rooms on the ward and taught their

locations on a corresponding map. He was trained to match the photographs to

their position on the map across three trials per session, followed by basic

sustained attention trials, before attempting delayed recall.

Occupational Therapists created an electronic reminder system on JRs phone,

sending him reminders before each therapy session began, to support

punctuality.

Outcome

JR was independently able to use the memory reminder system.

JR could use the system to orientate himself around the ward.

JRs punctuality improved for therapy sessions.

Procedure 2a

Despite JRs memory improvements he was unable to link his life events or

places he had lived in with his biographical memory. His memory training

optimised his recall, but more on a mechanical level.

He expressed that the events he had participated in had no meaning on a

personal or emotional level.

As a result he was unable to apply his learning to reality. As he began to gain

insight into his memory deficits and inability to emotionally connect to day-to-

day experiences, JR began to experience a loss of identity, which manifested

as low mood and reduced participation.

An intervention was designed to develop a timeline of JRs life, in collaboration

with JR. As JR expressed that music was a large part of his life, and given

research that suggests music therapy can support autobiographical memory

(Janata, Tomic & Rakowski, 2007; El Haj, Postal & Allain, 2012), JR was asked

to listen to popular music from the late 1970s to the early 2000s and recall

periods of his life and any specific autobiographical memories.

During the first session of the intervention, focussing on music from the late

1970s to the early 1990s, JR was able to recall the period of his life each song

reminded him of and could recall a specific autobiographical memory 85% of the

time. However, on the second and third session, JR could only recall

autobiographical memories 61.5% and 58.3% of the time, respectively. Despite

this, the autobiographical memories JR could recall were carried over to

subsequent sessions and other occasions.

JR began to show insight into the type of person he was through listening to the

songs and was able to reflect on his past emotional associations as the

intervention developed. This effect transferred to memories cued through

discussion, rather than music.

JR was able to build a collection of life events that helped define who he was

and was able to reflect on his emotions during past events, even when music

had not prompted recollection.

Finally, JRs mood and motivation with rehabilitation improved, which supported

his progress in other areas of rehabilitation more generally.

References: El Haj, M., Postal, V. & Allain, P. (2012). Music enhances autobiographical memory in mild Alzheimers Disease. Educational Gerontonolgy. 38: 30-41. Janata, P., Tomic, S.T. & Rakowski, S.K. (2007). Characterisation of

music-evoked autobiographical memories. Memory. 15: 845-860. Sohlberg, M.M., & Mateer, C.A. (1987). Effectiveness of an attention-training program. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology. 9: 117-130.

Wilson, B. A., Baddeley, A., Evans, J., & Shiel, A. (1994). Errorless learning in the rehabilitation of memory impaired people. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation. 4: 307-326. Wilson, B. A., & Gracey, F. (2009). Towards a

comprehensive model of neuropsychological rehabilitation. Cited in B. Wilson, F., Gracey & J.J. Evans [Eds.] Neuropsychological rehabilitation: Theory, models, therapy and outcome. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press

Contact: Dr Birgit Gurr , Neuropsychology Service, Dorset HealthCare, University NHS Foundation Trust, Poole Community Clinic ,Shaftesbury Road, Poole BH15 2NT, birgit.gurr@dhuft.nhs.uk

Cognitive rehabilitation is a comprehensive approach for improving cognitive

function via compensation or remediation (Wilson, 2002). Interventions are

based upon empirical models, such as attention-process training (i.e.

employing attention drills to support other cognitive functions, Sohlberg &

Mateer, 1987) or errorless learning (repeated errorless teaching of information

until perfect performance is achieved (Wilson et al., 1987).

Successful cognitive rehabilitation draws from more than one theoretical basis

in order to focus on a variety of elements of cognitive function (Wilson, 2002).

Cognitive rehabilitation should evolve throughout treatment according to the

patients emerging needs.

This poster presents a case study of a patient recovering from an acquired

brain injury and illustrates the importance of comprehensive and responsive

rehabilitation.

Patient Details:

JR, 47 year old, single man; previously worked as a laminator and DJ;

periods of social isolation.

Brain Injury Details:

Subarachnoid haemorrhage, intraventricular and intraparenchysmal

haemorrhage; found collapsed on floor.

Neuropsychological presentation:

Severe anterograde amnesia and retrograde amnesia; confabulations;

disorientation to time and place; anhedonia.

Initial rehabilitation aims:

Enhance orientation and confidence and improve learning potential.

You might also like

- Sensory Profiling Achieving Wellbeing and Planning For The Future in Early Onset DementiaDocument1 pageSensory Profiling Achieving Wellbeing and Planning For The Future in Early Onset DementiaJodiMBrownNo ratings yet

- West Dorset Early Supported Discharge For Stroke Significantly Above AverageDocument1 pageWest Dorset Early Supported Discharge For Stroke Significantly Above AverageJodiMBrownNo ratings yet

- Managing Cows Milk Protein Allergy in Infants in Primary CareDocument1 pageManaging Cows Milk Protein Allergy in Infants in Primary CareJodiMBrownNo ratings yet

- Peer Support in Early Intervention Helping Peers Help ThemselvesDocument1 pagePeer Support in Early Intervention Helping Peers Help ThemselvesJodiMBrownNo ratings yet

- Upper Limb GroupDocument1 pageUpper Limb GroupJodiMBrownNo ratings yet

- Occupational Therapy For Continuing Healthcare The Seeds of A New ServiceDocument1 pageOccupational Therapy For Continuing Healthcare The Seeds of A New ServiceJodiMBrownNo ratings yet

- Stroke Mood Screening On An Inpatient UnitDocument1 pageStroke Mood Screening On An Inpatient UnitJodiMBrownNo ratings yet

- Utilising The Expertise of Staff With Lived Experience of Mental Illness and Trauma To Improve PracticeDocument1 pageUtilising The Expertise of Staff With Lived Experience of Mental Illness and Trauma To Improve PracticeJodiMBrownNo ratings yet

- The Developing Face of Stammering Therapy in Dorset A Group Therapy ApproachDocument1 pageThe Developing Face of Stammering Therapy in Dorset A Group Therapy ApproachJodiMBrownNo ratings yet

- Socially Disengaged Not in Our Club Improving Inpatients Experiences and Clinical Outcome Through Group ActivitiesDocument1 pageSocially Disengaged Not in Our Club Improving Inpatients Experiences and Clinical Outcome Through Group ActivitiesJodiMBrownNo ratings yet

- Podiatric Surgery Stepping ForwardDocument1 pagePodiatric Surgery Stepping ForwardJodiMBrownNo ratings yet

- Recovery Skills Workshop Collaborative Working Between NHS Staff and Peer SpecialistsDocument1 pageRecovery Skills Workshop Collaborative Working Between NHS Staff and Peer SpecialistsJodiMBrownNo ratings yet

- Mentally Healthy Examining The Relationship Between Food Mood and MotivationDocument1 pageMentally Healthy Examining The Relationship Between Food Mood and MotivationJodiMBrownNo ratings yet

- Mindfulness Based Stress ReductionDocument1 pageMindfulness Based Stress ReductionJodiMBrownNo ratings yet

- Learn 2 Earn Optimistic Exploration of Vocational Opportunities For Young People With PsychosisDocument1 pageLearn 2 Earn Optimistic Exploration of Vocational Opportunities For Young People With PsychosisJodiMBrownNo ratings yet

- Communications Passports Getting Communication Right For EveryoneDocument1 pageCommunications Passports Getting Communication Right For EveryoneJodiMBrownNo ratings yet

- Keep On Walking Podiatry Service For Homeless and Vulnerable AdultsDocument1 pageKeep On Walking Podiatry Service For Homeless and Vulnerable AdultsJodiMBrownNo ratings yet

- Dont Choke On ItDocument1 pageDont Choke On ItJodiMBrownNo ratings yet

- Health and Wellbeing of People With Epilepsy and Non Epileptic Attack DisorderDocument1 pageHealth and Wellbeing of People With Epilepsy and Non Epileptic Attack DisorderJodiMBrownNo ratings yet

- Evaluation of A Life Skills Group For Brain Injury Patients On An Acute Neurological Rehabilitation UnitDocument1 pageEvaluation of A Life Skills Group For Brain Injury Patients On An Acute Neurological Rehabilitation UnitJodiMBrownNo ratings yet

- Assessing Learning Disability How Do Occupational Therapists Contribute To DiagnosisDocument1 pageAssessing Learning Disability How Do Occupational Therapists Contribute To DiagnosisJodiMBrownNo ratings yet

- Engaging With Life Through The Model of Human OccupationDocument1 pageEngaging With Life Through The Model of Human OccupationJodiMBrownNo ratings yet

- Abdominal Massage To Treat Chronic Constipation For People With Learning and Physical DisabilitiesDocument1 pageAbdominal Massage To Treat Chronic Constipation For People With Learning and Physical DisabilitiesJodiMBrownNo ratings yet

- Case Study Using The Kawa River Model As An Assessment and Intervention Planning ToolDocument1 pageCase Study Using The Kawa River Model As An Assessment and Intervention Planning ToolJodiMBrownNo ratings yet

- An Aspergers Service in Dorset Why Its Worth ItDocument1 pageAn Aspergers Service in Dorset Why Its Worth ItJodiMBrownNo ratings yet

- A Follow Up Study of Psychological Problems After StrokeDocument1 pageA Follow Up Study of Psychological Problems After StrokeJodiMBrownNo ratings yet

- Bridging The Gap Improving Transition and Independent Living Skills of Individuals With LDDocument1 pageBridging The Gap Improving Transition and Independent Living Skills of Individuals With LDJodiMBrownNo ratings yet

- A Survey of A Footwear Service For People With Rheumatoid ArthritisDocument1 pageA Survey of A Footwear Service For People With Rheumatoid ArthritisJodiMBrownNo ratings yet

- Clinicians Perceptions of Prescribing Antibiotics For Infections in The Diabetic FootDocument1 pageClinicians Perceptions of Prescribing Antibiotics For Infections in The Diabetic FootJodiMBrownNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- NERVOUS SYSTEM - pptx-2Document39 pagesNERVOUS SYSTEM - pptx-2jeffinjoffiNo ratings yet

- Consensus Statement On The Classification of Tremors, From The Task Force On Tremor of The International Parkinson and Movement Disorder SocietyDocument13 pagesConsensus Statement On The Classification of Tremors, From The Task Force On Tremor of The International Parkinson and Movement Disorder SocietyCarlos Gianpaul Rincón RuizNo ratings yet

- Nursing NotesDocument6 pagesNursing NotesAngel CauilanNo ratings yet

- Foster A Growth, Not A Fixed Mindset: Key FindingsDocument9 pagesFoster A Growth, Not A Fixed Mindset: Key FindingsPablo Barboza JimenezNo ratings yet

- R7410201 Neural Networks and Fuzzy LogicDocument1 pageR7410201 Neural Networks and Fuzzy LogicsivabharathamurthyNo ratings yet

- Predisposing and precipitating factors of spina bifidaDocument1 pagePredisposing and precipitating factors of spina bifidaKevinNo ratings yet

- NRSC500 Problem set: Key concepts in neurophysiologyDocument7 pagesNRSC500 Problem set: Key concepts in neurophysiologyAnonymous grcOYV49fZNo ratings yet

- Music and Altered States of Consciusness, Fachner JorgDocument23 pagesMusic and Altered States of Consciusness, Fachner JorgAnna Benchimol100% (1)

- (10920684 - Neurosurgical Focus) Tuberculum Sellae MeningiomasDocument6 pages(10920684 - Neurosurgical Focus) Tuberculum Sellae MeningiomasputriNo ratings yet

- Anaesthesia AS GuideDocument3 pagesAnaesthesia AS GuidethetNo ratings yet

- Psychological Effects of BullyingDocument11 pagesPsychological Effects of BullyingnyunsNo ratings yet

- Brain States Awareness Profile Certification Winter 2020Document1 pageBrain States Awareness Profile Certification Winter 2020Anonymous 1nw2cHNo ratings yet

- Exercise Induced Hypoalgesia After Acute And.11-2Document22 pagesExercise Induced Hypoalgesia After Acute And.11-2VizaNo ratings yet

- MS SymptomsDocument2 pagesMS SymptomsVennice Dela PenaNo ratings yet

- Reflex Testing Methods FOR Evaluating CNS Development: Charles C. Thomas PublisherDocument55 pagesReflex Testing Methods FOR Evaluating CNS Development: Charles C. Thomas PublisherDeborah Salinas100% (1)

- Quarter 2 Summative Science TestDocument4 pagesQuarter 2 Summative Science TestSharmaine RamirezNo ratings yet

- Vision Screening Form DepedDocument3 pagesVision Screening Form DepedAbigael Abac RiveraNo ratings yet

- The Importance of Diversity On Congitive NeuroscienceDocument11 pagesThe Importance of Diversity On Congitive NeuroscienceMarlon ChaconNo ratings yet

- 2 Myasthenia Gravis and MS 2Document50 pages2 Myasthenia Gravis and MS 2Rawbeena RamtelNo ratings yet

- Neurogenesis: The Amygdala and The HippocampusDocument3 pagesNeurogenesis: The Amygdala and The HippocampusAnonymous j3gtTw100% (1)

- German Neurologist On Face Masks Oxygen Deprivation Causes Permanent Neurological Damage PDFDocument4 pagesGerman Neurologist On Face Masks Oxygen Deprivation Causes Permanent Neurological Damage PDFOpieNo ratings yet

- Aetiopathogenesis and Pathophysiology of Bulimia Nervosa: Biological Bases and Implications For TreatmentDocument18 pagesAetiopathogenesis and Pathophysiology of Bulimia Nervosa: Biological Bases and Implications For TreatmentArmando Marín FloresNo ratings yet

- NCP Cva Impaired Physical MobilityDocument2 pagesNCP Cva Impaired Physical Mobilityexcel2112180% (5)

- Unit 13: Awareness of DementiaDocument7 pagesUnit 13: Awareness of DementiaLiza GomezNo ratings yet

- Mirroring People The Science of Empathy and How We Connect With OthersDocument330 pagesMirroring People The Science of Empathy and How We Connect With Othersggg3141550% (2)

- Medical Student Elective Book Spring 2020: Updated 08/13/2020Document234 pagesMedical Student Elective Book Spring 2020: Updated 08/13/2020ayeshaNo ratings yet

- Executive Functions by Thomas Brown 1Document6 pagesExecutive Functions by Thomas Brown 1api-247044545No ratings yet

- Instructional and Improvisational Models of Music Therapy With Adolescents Who Have Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD)Document153 pagesInstructional and Improvisational Models of Music Therapy With Adolescents Who Have Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD)ywwonglpNo ratings yet

- Excitable Tissue PhysiologyDocument13 pagesExcitable Tissue PhysiologyAlbert Che33% (3)

- Hermann Von HelmholtzDocument5 pagesHermann Von HelmholtzKshipra LodwalNo ratings yet