Professional Documents

Culture Documents

100%(1)100% found this document useful (1 vote)

14 viewsBorges: Man of Habits

Borges: Man of Habits

Uploaded by

jbmurrayPresentation on Borges.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5820)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (845)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (348)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- Homework Machine Dan GutmanDocument4 pagesHomework Machine Dan Gutmanafmshobkx100% (1)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

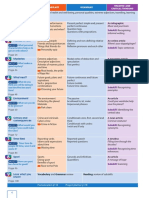

- Get Involved B1+ Student S Book Scope and SequenceDocument2 pagesGet Involved B1+ Student S Book Scope and SequenceCecilia Cardozo67% (3)

- Grammar WorkshopDocument12 pagesGrammar Workshopbej8011No ratings yet

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Ambleside Booklist Years 1 To 6 by Amy CorriganDocument7 pagesAmbleside Booklist Years 1 To 6 by Amy CorriganRachel Ginnett86% (7)

- Workbook For Norsk, Nordmenn Og Norge 1 - Beginning Norwegian, Second Edition - Norsk - 1Document203 pagesWorkbook For Norsk, Nordmenn Og Norge 1 - Beginning Norwegian, Second Edition - Norsk - 1Jason BrownNo ratings yet

- Detour - Session-1-Joseph & His FamilyDocument7 pagesDetour - Session-1-Joseph & His FamilySouthern LightNo ratings yet

- Term PaperDocument6 pagesTerm PaperRūta VolungevičiūtėNo ratings yet

- Ask and EmblaDocument4 pagesAsk and Embladzimmer6No ratings yet

- Harvard Style DissertationDocument5 pagesHarvard Style DissertationCustomCollegePaperUK100% (1)

- Apa Style Defined: Prepared by Ferdinand Makenji Velacruz EscalanteDocument11 pagesApa Style Defined: Prepared by Ferdinand Makenji Velacruz EscalanteMaKenJiNo ratings yet

- Mcqs in Orthodontics With Explanations For PG Dental Entrance Examinations 1st EditionDocument4 pagesMcqs in Orthodontics With Explanations For PG Dental Entrance Examinations 1st EditionYasir Israr0% (1)

- Tua and The Elephant Discussion GuideDocument2 pagesTua and The Elephant Discussion GuideChronicleBooksNo ratings yet

- Introduction To The Huayuanzhuang East Oracle Bone InscriptionsDocument70 pagesIntroduction To The Huayuanzhuang East Oracle Bone InscriptionsKary ChanNo ratings yet

- Root Base Law of Root 7-19Document16 pagesRoot Base Law of Root 7-19kdtomposNo ratings yet

- SanggunianDocument3 pagesSanggunianRose Ann AlerNo ratings yet

- Aspects of The Principate of Tiberius: Historical Comments On The Colonial Coinage Issued Outside Spain / by Michael GrantDocument233 pagesAspects of The Principate of Tiberius: Historical Comments On The Colonial Coinage Issued Outside Spain / by Michael GrantDigital Library Numis (DLN)No ratings yet

- Test Bank For Interpersonal Communication Relating To Others 7Th Edition Steven A Beebe Download Full Chapter PDFDocument26 pagesTest Bank For Interpersonal Communication Relating To Others 7Th Edition Steven A Beebe Download Full Chapter PDFjohn.padgett229100% (21)

- Grade-2 English 1st Quarter ExamDocument2 pagesGrade-2 English 1st Quarter Examruclito morataNo ratings yet

- Bibliographica Enochia: 1) Manuscripts in Institutional CollectionsDocument9 pagesBibliographica Enochia: 1) Manuscripts in Institutional CollectionsCelephaïs Press / Unspeakable Press (Leng)100% (4)

- Critical Essay About OrlandoDocument3 pagesCritical Essay About OrlandoJean Salcedo100% (1)

- Module 8 RizalDocument2 pagesModule 8 RizaljudayNo ratings yet

- Rizal OutlineDocument8 pagesRizal OutlineMartin ClydeNo ratings yet

- TTG PLTU BismillahDocument47 pagesTTG PLTU BismillahTikaTrianaNo ratings yet

- Hart 2005 CHPT 3 - Finding and Formulating Your Topic-1 PDFDocument42 pagesHart 2005 CHPT 3 - Finding and Formulating Your Topic-1 PDFMuhammadShahzebNo ratings yet

- Canterburry TaleDocument36 pagesCanterburry TaleGlare F DagyagnaoNo ratings yet

- Spider-Man Celebrates 60 Years With Deluxe Collector's HardcoverDocument7 pagesSpider-Man Celebrates 60 Years With Deluxe Collector's Hardcoverjavokhetfield5728No ratings yet

- FIN300 Syllabus Fall 2019Document16 pagesFIN300 Syllabus Fall 2019Spencer HikadeNo ratings yet

- A Letter From New York: Reading ComprehensionDocument3 pagesA Letter From New York: Reading ComprehensionClaudia ANo ratings yet

- Leading Well PreviewDocument15 pagesLeading Well PreviewGroup100% (1)

- Passover HaggadahDocument29 pagesPassover HaggadahVivian LeighNo ratings yet

Borges: Man of Habits

Borges: Man of Habits

Uploaded by

jbmurray100%(1)100% found this document useful (1 vote)

14 views8 pagesPresentation on Borges.

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentPresentation on Borges.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

100%(1)100% found this document useful (1 vote)

14 views8 pagesBorges: Man of Habits

Borges: Man of Habits

Uploaded by

jbmurrayPresentation on Borges.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 8

Jon Beasley-Murray

University of British Columbia

jon.beasley-murray@ubc.ca

Borges, Creature of Habits

If there is one theme that dominates both the work of Argentine writer Jorge Luis

Borges and that works critical reception, it is probably the relationship between the

particular and the general, the specific and the universal, the singular and the common.

To take but one example from Borgess own work: his early collection, A Universal

History of Iniquity, announces from its very title an ambition to say something about

iniquity (notoriety, deviance, violence) in general; but it does so by means of a series of

short, specific portraits of diverse and idiosyncratic figures, from The Cruel Redeemer,

Lazarus Morell to Hakim, the Masked Dyer of Merv or Mahomeds Double, all of

which are picked out, at times apparently almost by chance, from the breadth of

Borgess wide reading. It is far from clear what light this catalogue or dictionary of the

strange and perverse sheds on the category of the iniquitous as a whole. Indeed, one

possible conclusion to draw from the book is that its very approach undoes the project

announced in its title: that what, if anything, ironically unites its individual pieces is the

implicit demonstration that they do not and cannot make a whole, that there is no

universal history of iniquity to be told at all. There are only ever fragments, singular

instances, particular scenes or events that are inevitably traduced or betrayed by broad

abstractions or universalizing tendencies.

Elsewhere in Borgess fiction, it is not so much the general (or the desire for

generality) that betrays the specific, as the specific that undermines the general. In his

famous short story, The Aleph, for instance, the claim to have discovered a marvelous

union of all places and all times (from the populous sea to dawn and dusk, [. . .] the

multitudes of the Americas, [. . .] endless eyes, all very close, studying themselves in me

as though in a mirror, [. . .] all the mirrors on the planet [Collected Fictions 283]) is

undercut by its very specific and rather underwhelming location on a set of cellar stairs

in an unremarkable Buenos Aires house that is shortly due for demolition. This storys

narrator, asked to save the Aleph, this fantastic intimation of the universality, from its

imminent destruction by the vagaries of commercial development (the owners of the

Beasley-Murray, Borges, Creature of Habits 2

caf on the corner want to expand their premises), refuses to do so for the equally

particular (if not petty) reasons of personal dislike and latent jealousy towards the

houses owner. But ultimately, to say that the particular undermines the universal is

perhaps the same thing as to say that the universal (or the project of universalization)

only ever betrays and undoes the particular. Again, in some ways this is Borgess point

throughout his fiction: the relationship between the instance and what it is made more

broadly to represent (what it is an instance of) is always tense, antagonistic, hostile...

and yet somehow inevitable.

In the reception of Borgess work, this tension between specific and general plays

out in the divide between those who view him as primarily an Argentine writer, and

those who point rather to his claims to universality. One might imagine that the lines

between these positions also separate more political, materialist critics from the

traditionalists, but in fact things are rather more complicated: Borges has equally been

praised and damned for his particularities by politicized criticism, for instance. In part

this is because he does not fit easily into the postcolonial frame through which the

tension between general and specific has been increasingly viewed over the past thirty

years or so. He is not Argentine enough for those who want their writers to represent

some kind of (preferably indigenous) resistance to globalizing tendencies or the

presumed arrogance of so-called Eurocentrism, itself condemned as a particularism

disguised as universal. And yet of course the model of the resistant postcolonial writer

is itself a universalizing one that Borges discomfits precisely because he does not

exactly fit it very well. For such critics, he is insufficiently representative. On the other

hand, his perhaps peculiarly Argentine obsessions with the legacies of creole violence,

for instance, are part of what has prevented his full incorporation into the canon of

Western literature: thoroughly imbued in that canon himself, he also took the liberty of

taking pot shots at it from the margins. Indeed, it is as a writer of the margins that critic

Beatriz Sarlo observes that he somehow straddles the distinction between

cosmopolitanism and nationalism: he is the writer of the orillas, the banlieux or

disparaged suburbs on the outskirts of Buenos Aires expansive modernization, a

marginal in the centre, a cosmopolitan on the edge (Jorge Luis Borges 6). Yet Borges

himself, at least at times, seems to have wished to have been more universal, rather than

less. In response to a questionnaire in 1944, he said that his greatest literary ambition

was to write a book, a chapter, a page, a paragraph, that would be all things to all men

Beasley-Murray, Borges, Creature of Habits 3

. . . that would dispense with my aversions, my preferences, my habits (qtd. in

Williamson 279). For good or ill, however, Borges failed in this ambition; he remained a

creature of habit.

It is habit, however, that may help us resolve this apparent antimony between

the particular and the general, perhaps even in a (properly posthegemonic) way that

also loosens the bind of representation as an ambition that necessarily fails in its desire

to make the one always the instance of the other. For habit is both singular and general

without ever being anything other than what it is. Habits are both individual and

shared, distinctive without being essential: we are the sum of our habits, and yet no

specific habit defines us. All habits are acquired--none is innate--and yet they tend to

persist, and we persist with them. We transform them (and so ourselves) only with

difficulty, but as we do so we construct new forms of community, new modes of living

in common. Yet the trace of our past lives continues in the habits that we cannot quite

leave behind altogether.

Take for instance the tale of The Disinterested Killer Bill Harrigan, which, like

many others in Borgess Universal History, is a story of metamorphosis and performative

adaptation. Here, New York tenement boy Harrigan turns himself into the cowboy out

West who will be Billy the Kid by acting out melodramatic models provided by the

theater. In turn, he will become an iconic part of the myths of the Wild West propagated

by Hollywood. The key scene in this self-remaking, of Harrigans becoming Billy, is the

point at which a notorious Mexican gunfighter named Belisario Villagrn enters a

crowded saloon that is outlined with cinematic precision and visuality (their elbows

on the bar, tired hard-muscled men drink a belligerent alcohol and flash stacks of silver

coins marked with a serpent and an eagle [Collected Fictions 32]); everyone stops dead

except for Harrigan, who fells him with a single shot and for no apparent reason. In that

moment, Billy the Kid is born and the shifty Bill Harrigan buried (33). But even if it is

Bills disinterested (unreflective, habitual) killing that turns him into a legend (a

general type), there is always a gap between that legend and his behavior. He may learn

to sit a horse straight or the vagabond art of cattle driving and he may find himself

attracted to the guitars and brothels of Mexico (33, 34), but a few tics from his East

Coast days remain: Something of the New York hoodlum lived on in the cowboy (33).

The task of replacing one set of habits (or habitus) with another is never quite complete.

It is not as though Harrigan were the real thing and Billy the Kid a mere mask.

Beasley-Murray, Borges, Creature of Habits 4

Rather, it is that the new performance is informed by the old one. As always in Borges,

there is never anything entirely new under the sun, even the scorching sun of the arid

Western desert.

The focus on a pivotal moment in Bill Harrigan (and indeed, in many other of

the stories in the same collection) is unusual in its clarity. Borgess later stories tend to

describe a series of minor deviations, none of which is in itself crucial, but which

collectively have unexpected results. Perhaps the classic example of this is The Garden

of Forking Paths, but in fact we see it everywhere, as he elaborates the mutual

implication of, on the one hand, static scenes whose drama often derives from the

structural logic of genre fiction or the cinema and, on the other hand, plot development

guided by the logic of an accumulation of almost imperceptible (and seemingly

random) deviations from the norm. In various stories he then explores the diverse

possible relations between what we can call the logic of minimal deviation and the

structure of the scene. Sometimes one leads to the other, sometimes the two

complement each other, sometimes they are in tension, and so on. At times Borges

seems to be asking how much deviation (or how many minimal deviations) are

required to provoke a scene. At other times he wonders how many deviations any

particular scene can handle. And there are still other cases in which he proposes that it

is only by making a scene that the logic of gradual accumulation can be brought to a

halt. Take Death and the Compuass, for instance. Here the detective, Lnnrot,

carefully and slowly follows the periodic series of bloody deeds (147), each of which

is but a slight variation on its predecessor, until he arrives at the climactic scene that

gives (renewed) sense to the series itself. Or Tln, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius, which begins

with a paradigmatic scene: a dinner with Borgess friend Bioy Casares, a glance at a

mirror that provokes a citation and then the fruitless search for its origin. This then

opens up a concatenation of curious circumstances, each one of which could easily be

overlooked: an additional encyclopedia article, a package from Brazil, a compass

packed in a crate of table service, a dead man who owns an unusually heavy metal

cone. Together, however, they constitute a new world. In all these cases (and others:

The Secret Miracle, for instance), what is at issue is the connection between habit or

the routine, with its many repetitions none of which is quite like the last, and drama or

the exceptional. How does the dramatic scene, with all its novelty, arise from routine

repetition? Why is it that we are suddenly confronted with a decision or choice that

Beasley-Murray, Borges, Creature of Habits 5

only in retrospect we can understand has been a long time brewing in all the vagaries of

chance? Or how, by contrast, does the scene itself become routinized or habitual?

We see the same logic also in The South, where it is not so much that there is

any single one crux in the process whereby (here) a mild-mannered urban librarian

finds himself, if only in his imagination, ultimately in the thick of a knife fight on the

pampa, the most classic of scenes from the mythology of the Western. There are, rather,

many points of slight divergence from the routine, all of which cumulatively lead the

plot to its narrative conclusion, and the storys protagonist, Juan Dahlmann, to his

untimely end. But each of these pivots on which the story and Dahlmanns fate rests is

presented as the lightest of touches: literally so, in the instance of the injury that leads

him to septicemia and the sanatorium. Fate can be merciless with the slightest

distractions, comments the storys narrator, as he explains that his protagonist makes a

slight change in his usual routine when he takes the stairs rather than the elevator; on

the way up, something in the dimness brushed his foreheada bat? a bird? [. . .] The

hand he passed over his forehead came back red with blood (174-175). Yet it is this

slightest of grazes that infects him with septicemia and leads him to the clinic from

which the rest of the story unfolds. The choices we make only half-aware (taking the

stairs rather than the elevator) combine with half-noticed events (a brush on the

forehead) to produce unexpected and sometimes fatal results. This particular event is

later mirrored when, in a store in the south of the storys title, Dahlmann suddenly felt

something lightly brush his face (278). But it would be wrong to say that it is his

reaction to this encounteraccepting a young thugs challenge to a fightthat seals his

fate. For one thing, whats required is the intervention of yet another unforeseeable

intervention, a gaucho throwing Dahlmann a weapon; for another, we might also say

that our protagonists conclusion has been inscribed in his ancestry, his grandfathers

own death fighting in the south, and the pull of that lineage. The logic of habit

suggests that one thing tends to lead to another, but this is only a tendency, not an iron

law of fate or history. Or perhaps it would be better to say that this is what fate and

history are for Borges, this is their iron law: no more and no less than an accumulation

of almost imperceptible (and seemingly random) deviations from the norm.

In this proliferation of endless differences that undermine any stable identity and

undo any project of representation (and so, by inference, hegemony), the wonder is that

anything survives at all. If we are only one step from chaos and violent disintegration,

Beasley-Murray, Borges, Creature of Habits 6

the issue is less how we prevent that step than how we emerged from that flux in the

first place. For Borges, the true mystery is not the endless division and uncertainty.

Time passes, things change, moment to moment everything is up in the air; neither

language nor reason can hold things still within their prisons of representation or

categorization. I is always another. It could not be otherwise. No, the real surprise is

that despite all this mutability and malleability, some things somehow do seem to

remain the same. It is, in short, not the singular or the so-called exceptional that requires

explanation, but the common, the fact that from a universe of chance emerge islands of

relative predictability and consistency. Here again, however, habit is our guide as its

tendency to persist constitutes a conatus (both individual and collective) that tends to

ensure longevity and survival. It may be mere illusion (though what could be less

illusory than habit?), but we do think--or better, as Borges puts it, feel--that we

incarnate some kind of singularity that is more or less the same today as it was

yesterday. This is a concern of Borgess from his very first publication, the collection of

poetry entitled Fervor de Buenos Aires, which (among other things) is devoted to the

unsettling displacements of the citys insistent expansion and modernization--the same

developments that doom the Aleph. In a brief poem entitled Final del ao (Years

End), he concludes by pointing to the:

wonder in the face of the miracle

that despite the infinite play of chance

that despite the fact that we are but

drops in Heraclituss river,

something still endures within us:

unmoved. (Obras completas I 50)

Much later, in Borges and I, this endurance is explicitly linked to Spinozas notion of

conatus: the idea that all things with to go on being what they are--stone wishes

eternally to be stone, and tiger, to be tiger. The twist then that Borges adds is that this

persistence and survival is thanks to a series of public performances that take on the

proper name from which he himself feels increasingly distant: I shall endure in Borges,

not in myself (if, indeed, I am anybody at all) (Collected Fictions 324). Little by little, he

Beasley-Murray, Borges, Creature of Habits 7

has become general, the property of all. His habits, in other words, have taken on a life

of their own: Borges finds that he is nothing more, if nothing less, than their creature.

Finally, then, what I hope to have begun to sketch is a Borges who is neither

particular nor general, specific nor universal, but a writer in the process of becoming

common through the development and pursuit of a series of habits that both change

and persist over the course of his career. Indeed, we see this process mirrored in the

formal aspects of his work, as a writer of short fictions that ceaselessly return to what

are often very similar preoccupations and scenes, none of which can be completely

reduced to any other, as they continuously incarnate slight deviations at the very

moment of their repetition. Or to put this another way: to see these stories in terms of

some kind of chain of equivalence is to ignore the diversity that they both thematize

and problematize. They work, moreover, not in terms of simple representation (or

allegory), given that one of themes to which they constantly return is precisely the ways

in which representation betrays and is betrayed by the specific instances that constitute

it. Rather, Borgess work serves to inculcate certain habits of reading that are attentive

both to the return of the familiar and to the emergence of drama, the construction of a

scene, in the slight deviations that provoke anxiety and humor alike. Borges, creature of

habits, passes on some of these habits to his readers as well as, by making us if only

intermittently alive to them, wresting from us some of the habits that are already ours.

Beasley-Murray, Borges, Creature of Habits 8

works cited

Borges, Jorge Luis. Obras completas I: 1923-1936. Buenos Aires: Crculo de Lectores, 1992.

-----. Collected Fictions. Trans. Andrew Hurley. London: Penguin, 1998.

Sarlo, Beatriz. Jorge Luis Borges: A Writer on the Edge. Ed. John King. London: Verso,

2006.

Williamson, Edwin. Borges: A Life. London: Penguin, 2004.

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5820)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (845)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (348)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- Homework Machine Dan GutmanDocument4 pagesHomework Machine Dan Gutmanafmshobkx100% (1)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Get Involved B1+ Student S Book Scope and SequenceDocument2 pagesGet Involved B1+ Student S Book Scope and SequenceCecilia Cardozo67% (3)

- Grammar WorkshopDocument12 pagesGrammar Workshopbej8011No ratings yet

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Ambleside Booklist Years 1 To 6 by Amy CorriganDocument7 pagesAmbleside Booklist Years 1 To 6 by Amy CorriganRachel Ginnett86% (7)

- Workbook For Norsk, Nordmenn Og Norge 1 - Beginning Norwegian, Second Edition - Norsk - 1Document203 pagesWorkbook For Norsk, Nordmenn Og Norge 1 - Beginning Norwegian, Second Edition - Norsk - 1Jason BrownNo ratings yet

- Detour - Session-1-Joseph & His FamilyDocument7 pagesDetour - Session-1-Joseph & His FamilySouthern LightNo ratings yet

- Term PaperDocument6 pagesTerm PaperRūta VolungevičiūtėNo ratings yet

- Ask and EmblaDocument4 pagesAsk and Embladzimmer6No ratings yet

- Harvard Style DissertationDocument5 pagesHarvard Style DissertationCustomCollegePaperUK100% (1)

- Apa Style Defined: Prepared by Ferdinand Makenji Velacruz EscalanteDocument11 pagesApa Style Defined: Prepared by Ferdinand Makenji Velacruz EscalanteMaKenJiNo ratings yet

- Mcqs in Orthodontics With Explanations For PG Dental Entrance Examinations 1st EditionDocument4 pagesMcqs in Orthodontics With Explanations For PG Dental Entrance Examinations 1st EditionYasir Israr0% (1)

- Tua and The Elephant Discussion GuideDocument2 pagesTua and The Elephant Discussion GuideChronicleBooksNo ratings yet

- Introduction To The Huayuanzhuang East Oracle Bone InscriptionsDocument70 pagesIntroduction To The Huayuanzhuang East Oracle Bone InscriptionsKary ChanNo ratings yet

- Root Base Law of Root 7-19Document16 pagesRoot Base Law of Root 7-19kdtomposNo ratings yet

- SanggunianDocument3 pagesSanggunianRose Ann AlerNo ratings yet

- Aspects of The Principate of Tiberius: Historical Comments On The Colonial Coinage Issued Outside Spain / by Michael GrantDocument233 pagesAspects of The Principate of Tiberius: Historical Comments On The Colonial Coinage Issued Outside Spain / by Michael GrantDigital Library Numis (DLN)No ratings yet

- Test Bank For Interpersonal Communication Relating To Others 7Th Edition Steven A Beebe Download Full Chapter PDFDocument26 pagesTest Bank For Interpersonal Communication Relating To Others 7Th Edition Steven A Beebe Download Full Chapter PDFjohn.padgett229100% (21)

- Grade-2 English 1st Quarter ExamDocument2 pagesGrade-2 English 1st Quarter Examruclito morataNo ratings yet

- Bibliographica Enochia: 1) Manuscripts in Institutional CollectionsDocument9 pagesBibliographica Enochia: 1) Manuscripts in Institutional CollectionsCelephaïs Press / Unspeakable Press (Leng)100% (4)

- Critical Essay About OrlandoDocument3 pagesCritical Essay About OrlandoJean Salcedo100% (1)

- Module 8 RizalDocument2 pagesModule 8 RizaljudayNo ratings yet

- Rizal OutlineDocument8 pagesRizal OutlineMartin ClydeNo ratings yet

- TTG PLTU BismillahDocument47 pagesTTG PLTU BismillahTikaTrianaNo ratings yet

- Hart 2005 CHPT 3 - Finding and Formulating Your Topic-1 PDFDocument42 pagesHart 2005 CHPT 3 - Finding and Formulating Your Topic-1 PDFMuhammadShahzebNo ratings yet

- Canterburry TaleDocument36 pagesCanterburry TaleGlare F DagyagnaoNo ratings yet

- Spider-Man Celebrates 60 Years With Deluxe Collector's HardcoverDocument7 pagesSpider-Man Celebrates 60 Years With Deluxe Collector's Hardcoverjavokhetfield5728No ratings yet

- FIN300 Syllabus Fall 2019Document16 pagesFIN300 Syllabus Fall 2019Spencer HikadeNo ratings yet

- A Letter From New York: Reading ComprehensionDocument3 pagesA Letter From New York: Reading ComprehensionClaudia ANo ratings yet

- Leading Well PreviewDocument15 pagesLeading Well PreviewGroup100% (1)

- Passover HaggadahDocument29 pagesPassover HaggadahVivian LeighNo ratings yet