Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Robbins, 2005. The Look of Success

Uploaded by

Yurii RiiañoOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Robbins, 2005. The Look of Success

Uploaded by

Yurii RiiañoCopyright:

Available Formats

The Look of Success

In the wake of successful wolf reintroductions, managers who once fervently defended

wolves are now faced with killing them. Are we ready for modern predator management?

By Jim Robbins

October-December 2005 Vol. 6 No. 4

For most of the 1990s, Ed Bangs, head of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Services

Endangered Species Office, helped truck wolves from Canada to the U.S. and was

instrumental in establishing the first pack in the Northern Rockies in more than half a

century. For years he nurtured them and protected them from poachers.

A decade later, the return of the wolf has been wildly successful. Since 1994, their

number has gone from a handful to more than 850 and continues to grow. They will

likely soon colonize new states, including Oregon and Colorado. The job of taking care

of the wolf population has changed, too.

Now the job is to protect the species in a different way: by killing as ruthlessly as

possible those wolves that show a proclivity for livestock. Bangs and state biologists in

Montana and Idaho find professional hunters to shoot the wolves from helicopters or

fixed-wing aircraft or to track them on the ground and kill them. Sometimes the hunters

kill a lone wolf; sometimes they kill a whole pack, pups and all. To do the latter, they

catch a wolf, collar it, and allow it to return to its pack. Tuning in to the transmitter, they

follow this so-called Judas wolf as it visitsand betraysits pack-mates. The hunters

kill them one by one. If theres no alternative, we kill a couple of wolves, said Bangs.

And we keep killing them until we run out of wolves or the problem stops. The irony

is not lost on Bangs.

***

The American West is getting wild again. Half a century after the wolf was dynamited in

its den, hunted, trapped, and poisoned out of the West, it has reclaimed the northern

Rockies. This is one of the fastest recoveries of an endangered species on record, and few

expected so many wolves would come back so quickly.

The return of the gray wolf (Canis lupus) has become one of the most controversial

wildlife issues in the U.S. While people in Alaska and the northern Midwest have long

lived with wolves, the wolves were gone for so long in the West that their return to daily

life has been a shock. This is partly because wolves touch something very deep in the

reservoir of human emotiona depth to which few other animals come closeyet at

opposite ends of the spectrum. Some respond to a wolf howl with shivers of delight, but

for others that same ululating howl evokes chills of fear.

But the return of the wolf clearly demonstrates something else. Wildlife management has

changed dramatically since the last wolf was wiped out some 60 years ago. Although the

northern Rocky Mountains contain millions of hectares of federally protected wilderness

and parks, much of the area is covered by snow and ice for more than half the year.

Wolves, like people, want to live in the more hospitable valley bottoms. But thats where

rural subdivisions have spread unchecked and where people keep everything from llamas

to horses to potbellied pigs and dogs and where ranchers graze cattle and sheep. Its all

too tempting a target for some wolves.

So the diminishing wilderness has met the computer age to create what some callonly

half in jestrobo-wolf. Managing wolves in this New West is an intensive process

with radio and GPS-collared animals that are tracked down when they kill, night-vision

scopes for those who hunt wolves, and electronic guard systems that are activated by

wolves wearing special electronic collars. This technology may well be the harbinger of

future predator management.

***

Canis lupus is arguably the most charismatic of what biologists refer to as charismatic

megafaunawildlife with sex appeal and the fierce public support that seldom

materializes for the Wyoming toad or the short-nosed sucker fish. This is so, at least in

part, because the wolf is a social animal that loves, mates, and rears its young much like

humans do. On the other hand, there are deeply ingrained stories about the dark side of

the big bad wolf.

When people start talking about wolves, says Bangs, who has spent the last 17 years

meeting with people passionate one way or the other about these predators, within

seconds they are talking about something elsetheir childrens heritage, the balance of

nature, someone else telling you what to do. A lot of people get tears in their eyes and

start sobbing. Managing the wolf is managing a symbol.

As a consequence, he says, wolves are managed much more intensively than any other

animal. People on both sides want to know where wolves are. Last year, for example,

the Montana legislature passed a law mandating that every wolf pack in Montana have at

least one wolf with a radio collar.

The wolfs Rocky Mountain homecoming offers tourists and naturalists the breath-

stealing sight of a pack of the long-legged hunters loping across a grassy meadow or

sunning themselves, drunk on meat, on a Yellowstone Park hillside. But because no

predator kills as often or with the same savagery as a pack of wolves, it has also meant a

return to raw, frontier-style brutality in the Rocky Mountain Westnot just by wolves

but by the people charged with managing them. And because American culture idealizes

wildlife, the killingon both sideshas come as a shock.

The killing has been ratcheted up in recent years as the animals numbers have grown.

From a few dozen animals at reintroduction, there are now around 850. This increase has

occurred much more rapidly than expected: biologists had predicted there would be

around 500 at this point. Wolves kill often, for each wolf needs an average of 4 kg of

meat daily. They also travel far and wide, and each pack has a home range of 650 to over

1,300 km2.

Because the West is growing ever more crowded and the habitat ever more fragmented,

officials say there is no way to keep the wolves in the West without constantly

monitoring, shooting, and trapping them. The current population of wolves is growing

annually by 30 percent, which can take a toll on peoples livelihoods. The key to

keeping the wolf around is human tolerance, Bangs says. The only reason wolves

disappeared is because we killed them all. How do you kill the minimum you need to

maintain human tolerance so we dont kill them all again? You kill problem wolves.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service goal is to have at least one member of almost every

pack fitted with a radio collar so that the packs whereabouts is always known. There are

110 packs in the three states, ranging from just two wolves to ten or so in each pack.

Lone wolves who take livestock are hunted down and killed almost immediately.

Trespassing packs are dealt with harshly: they are repeatedly trapped, drugged, harassed,

andif they continue to range too close to people and livestockdispatched with

extreme prejudice. More than 300 wolves have been shot by federal agents since 1987, a

practice known as lethal control.

Wolves in Yellowstone National Park get even more hardware. In the Parks twelve wolf

packs, two to four wolves in each pack are fitted with collars. Some collars beam the

wolfs whereabouts to a GPS satellite 48 times a day. Biologists in the field can

download that information into a receiver if they are within a kilometer or so of the

animal. New-generation collars bounce the wolfs location off a satellite to a computer

which then e-mails the wolfs whereabouts to researchers. The biologist doesnt even

have to leave the office.

With such intensive management, some say, the Wests wildlife is less than truly wild.

But ultimately, it may be the only way to keep predators around. If we dont have

information, then we cant manage them, and without that, they dont stand a chance of

surviving in this humanized environment, says Douglas Smith, National Park Service

wolf biologist.

***

A meeting of ranchers about wolves sounded like Tales from the Crypt for the

agricultural set. Three ranchers who had suffered wolf attacks quietly related story after

story about wolves howling around their homes at night, about coming home to find

frightened, bawling, huddled cows circled by wolf tracks in the snow, about the empty

feeling in the pit of the stomach when they see buzzards circling their pasture, and about

cows who have trampled calves while fleeing approaching wolves. It makes the hair

stand up on the back of your neck to hear 75 or 80 cows screaming at the top of their

lungs, says Randy Peprich, a lean, bearded rancher in the Paradise Valley north of

Yellowstone National Park who has had numerous wolf depredations on his ranch. I

never heard a cow scream until the wolves came back.

Ranchers are not the only ones struggling to acclimate themselves to wolves. Owners of

rural residential homes, which have sprung up throughout Montana during the past

several decades, have also discovered the wolf at their door and observed the predator-

prey relationship disconcertingly play out in the front yard among the tulips and

daffodils. A helicopter pilot flying over Ninemile Valley near Missoula watched as two

wolves chased three deer in circles around a house.

The Ninemile, situated a few hundred kilometers north of Yellowstone, is home to a large

population of wolves. Motion picture actress Andie McDowell lived here for several

years in the 1990s when the wolves were first colonizing the valley. She spoke out in

support of the wolves, says Bangs, but her enthusiasm waned after the two Great

Pyrenees guard dogs she had bought to protect her children were slaughtered by wolves.

One was found half-eaten under the swing set. She wasnt against wolves after that,

says Joe Fontaine, a wildlife specialist who works for Bangs. She just didnt speak out

in favor of them.

The reality of the predator-prey relationship can test the mettle of even the most ardent

wolf supporters. A saddle horse in the Ninemile, for example, was apparently set upon by

wolves and galloped away, so frantic and blinded by fear that it impaled itself on the end

of a 10-cm diameter irrigation pipe. It managed to free itself and run a short way before

collapsing and being eaten.

Wolves that kill livestock are a minority; most stay with a wild diet. But from the first

attacks in1987 until the end of 2004, wolves have dropped 429 head of cattle, 1,074

sheep, 9 llamas, 12 goats, and 4 horses. This may seem like a lot, but Its so low, says

Bangs. Its half of what we thought it would be. And if it werent for ongoing efforts

by federal agents, the toll would have probably been much higher.

Federal biologists have tried in several ways to make the situation tenable for ranchers

and rural homeowners. Those with wolves nearby are often given antennas and receivers

so they can track the wolves. They are sometimes given rubber bullets, bean bags, and

other less-than-lethal kinds of weapons. Ranchers in Montana and Idaho are allowed to

shoot wolves now, but only if they see them attacking livestock.

***

Some environmentalists do not accept as a given the need to kill wolves. Defenders of

Wildlife, a Washington, D.C.-based environmental group, lobbied for years to return the

wolf to the Western wilds, and now it wants to protect those animals. It has paid out more

than half-a-million dollars to reimburse ranchers for dead livestock in an effort to make

the wolf politically acceptable. The organization is also pioneering nonlethal methods of

keeping wolves away.

With hundreds of red flags fluttering in the breeze, the lower sheep pasture at one ranch

looked like a used-car lot. A European innovation, fladry appears to keep wolves away

by scaring them. It usually works for only a month or two, after which the wolves

become habituated. But its better than nothing and can be used at key times. Researchers

are also testing turbo fladry, where an electrical current runs through a wire threaded

through the flags.

Some wolves are fitted with a RAG (radio-activated guard) collar, which trips an

electronic alarm when the wolf approaches. The alarm plays taped sounds of glass

breaking, people yelling, sirens, gunfire, and explosions.

The best defense against marauding wolves is human presence, and so Defenders of

Wildlife has created the Wolf Guardian Project. At their own expense, deeply committed

volunteers, including students and housewives, camp out in remote mountain pastures

during lambing and other critical times of the year.

Anything that makes it not worth the risk for the wolves can help avoid or reduce

depredations, said Suzanne Asha Stone, the Northern Rockies Representative for

Defenders of Wildlife. The guardians track the wolfs radio collar and, when the wolf

approaches, whoop it upyelling, banging pots and pans, firing off firecrackers.

There are, however, only so many guardians to go around. So the go-to strategy remains

shooting the problem wolves. The killing is usually carried out by Wildlife Services, a

division of the Department of Agriculture that hunts down nuisance wildlife and is good

at what it does. Officials are apparently also worried that the public will find out, for

whereas the press can ride with the Marines into Baghdad, no one gets to see what

Wildlife Services is doing to wolves with taxpayer dollars. A request to a public affairs

officer with the Department of Agriculture in Denver to accompany an agent on a lethal

control action was refused. The business of killing wolves is better done out of view of

the public.

***

So is this what we wanted? And if not, what did we expect? The case of wolf

reintroduction into the western U.S. raises some uncomfortable questions about predator

conservation in the modern world. Do we want to reintroduce predators for their role in

ecosystems, or are we just trying to recapture a symbol of the wild? Despite our best

intentions, how much wildness are we willing to tolerate? And is the hyper-

management worth it? I think its kind of ridiculous, myself, says Bangs. We dont do

it with any other animal in North America. Theres a lot to be said for ignorance and

mystery. The essence of wilderness and the wild is its unpredictability.

BOX: Living with WolvesThe European Counterpart

In 1978 biologist Petter Wabakken arrived in Hedmark, Norway, to begin teaching

wildlife biology at the local college. He heard from local hunters that they had seen wolf

tracks but that no one had believed them. Wabakken decided to find out for himself. In

the no-mans land that is the Swedish-Norwegian border, Wabakken found a solitary

wolf pair. Three decades later and after dozens of scientific publications, countless cold

winter days spent following wolf tracks, and the arrival of a third wolf in 1991, the

population exploded.

Now the Scandinavian wolf pack numbers more than 100. Their presence has put Norway

and Sweden on notice: as signatories to the 1970 Bern convention, the two countries had

pledged to protect and restore the biological integrity of their native animal communities.

But the rapidly expanding wolf population would put that resolve to the test.

A similar story is playing out in the rest of Europe. European wolves, exterminated from

virtually every central and northern European country by the end of the Second World

War, are coming back. Wolves roam the plains of central Spain and the vast arctic tundra

of Finland and Karelia; they are found in great numbers in the deep forests of Romania

and the sunbaked hills of Greece. All told, 25 European countries are now home to

wolves, with the number likely to expand as wolves migrate from current population

strongholds to Austria, Belgium, Denmark, The Netherlands, and Luxembourg.

If the wolf is ever going to find a permanent, welcoming home in Europe, Scandinavia

ought to be it. Norway and Sweden are wealthy, liberal democracies with a sense of the

natural world so integral to the Scandinavian identity that it is recorded in thousand-year-

old Norse myths. But Scandinavians are grappling with the challenge of modern predator

management. The farmers remember when their parents worked hard to get rid of

wolves, and now the city folk are coming and telling them they have to have wolves

again, says Olof Liberg, a Swedish researcher at the Grims Wildlife Research Station

and coordinator of SKANDULV, the Scandinavian Wolf Research Project.

But does this mean it cant work? Not if you ask the Swedes. Swedish officials have

found a successful formula for protecting their wolf population. Farmers who have

livestock in wolf areas can apply for money to build fences and other protective

structures; if a wolf takes an animal, the state will also pay compensation for the lost

livestock. Wolf biologist Luigi Boitani of the University of Rome, Italy, says that Sweden

has been the most successful of all European nations in integrating science into public

policy when it comes to wolves.

But just over the border in Norway, the growing wolf population was greeted with

gunshot salvos after the Norwegian government elected in Spring 2005 to cull one-fifth

of the countrys population of 25 animals. Norwegian farmers are also paid compensation

if they lose livestock to wolves, but Norways sheep population of more than 2 million

animals is nearly five times larger than Swedensand Norwegian sheep are allowed to

roam the mountains freely to graze in the summer.

Scientists have responded to the challenge by using innovative approaches to keep tabs

on wolf populations. The Scandinavian Wolf Research Project, for example, is

sponsoring a wolf hot line in association with hunter groups. Hunters can call the hot line

and find out whether wolf packs are in the areas where they plan to hunt. The hope is that

fewer hunting dogs will fall prey to packs. And in a region where virtually every self-

respecting citizen owns a cell phone, Scandinavians have figured out how to give wolves

cell phones, too. One wolf was fitted with a special collar that held a cell phone instead of

a radio transmitter. Every time the wandering wolf neared a cell-phone tower, the phone

sent a text message, allowing researchers to track the wolfs movements.

By Nancy Bazilchuk

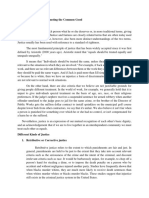

Table: Current European Wolf Numbers1

Select countries:

Belarus 2000-2500

Bulgaria 800-1000

Croatia 100-150

France 100

Greece 1500-2000

Italy 400-500

Lithuania 600

Macedonia >1000

Norway 25

Romania 2500

Spain 2000

Sweden 150

Ukraine 2000

Table Caption: The main conservation issue in Europe is the incongruence between

biological and administrative units. For example, although wolf numbers per country are

used for policy and administrative purposes, there are actually only six major biological

populations of wolves across Europe.

1Personal communication with Luigi Boitani, Department of Animal Biology, University

of Rome, Italy.

About the Author

Jim Robbins lives in Montana and has written about wolves since the first animals

returned to the state in the early 1980s. He has written two books and many articles about

environmental issues for The New York Times, Discover, Audubon, and Cond Nast

Traveler.

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5795)

- Esfandiari, 2021Document10 pagesEsfandiari, 2021Cássia Fernanda do Carmo AmaralNo ratings yet

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- The Cottage in The Woods by Katherine Coville - Chapter SamplerDocument40 pagesThe Cottage in The Woods by Katherine Coville - Chapter SamplerRandom House KidsNo ratings yet

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Consumer Protection Act, ProjectDocument17 pagesConsumer Protection Act, ProjectPREETAM252576% (171)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Generacion de Modelos de NegocioDocument285 pagesGeneracion de Modelos de NegocioMilca Aguirre100% (2)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Bucket 33 XS02544835961 66498 8332760Document5 pagesBucket 33 XS02544835961 66498 8332760Hyunjin ShinNo ratings yet

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Technical Information: Spare Eebds Mentioned in Item 1 Are Not To Be Included in Total NumberDocument5 pagesTechnical Information: Spare Eebds Mentioned in Item 1 Are Not To Be Included in Total NumberSatbir SinghNo ratings yet

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Bible Study MethodsDocument60 pagesBible Study MethodsMonique HendersonNo ratings yet

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Improve Web-UI PerformanceDocument4 pagesImprove Web-UI Performancekenguva_tirupatiNo ratings yet

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Blackpink Interview in Rolling StoneDocument8 pagesBlackpink Interview in Rolling StoneNisa Adina RNo ratings yet

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Sistemas de Control para Ingenieria 3 EdDocument73 pagesSistemas de Control para Ingenieria 3 EdNieves Rubi Lopez QuistianNo ratings yet

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Issue 6Document8 pagesIssue 6Liam PapeNo ratings yet

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Tomas CVDocument2 pagesTomas CVtroy2brown0% (1)

- Kasra Azar TP2 Lesson PlanDocument6 pagesKasra Azar TP2 Lesson Planکسری آذرNo ratings yet

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Soal Usp Bhs InggrisDocument4 pagesSoal Usp Bhs InggrisRASA RASANo ratings yet

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- UGC NET - Strategic ManagementDocument101 pagesUGC NET - Strategic ManagementKasiraman RamanujamNo ratings yet

- Haramaya University: R.NO Fname Lname IDDocument13 pagesHaramaya University: R.NO Fname Lname IDRamin HamzaNo ratings yet

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- 1 Crim1 - People Vs Javier - Lack of Intent To Commit So Grave A WrongDocument2 pages1 Crim1 - People Vs Javier - Lack of Intent To Commit So Grave A WrongJustin Reden BautistaNo ratings yet

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1091)

- CatalogDocument11 pagesCatalogFelix Albit Ogabang IiiNo ratings yet

- ZONE A - Walled City ReportDocument49 pagesZONE A - Walled City ReportAr Vishnu Prakash0% (1)

- LEGAL AND JUDICIAL ETHICS - Final Report On The Financial Audit in The MCTC - AdoraDocument6 pagesLEGAL AND JUDICIAL ETHICS - Final Report On The Financial Audit in The MCTC - AdoraGabriel AdoraNo ratings yet

- Tunisia Tax Guide - 2019 - 0Document10 pagesTunisia Tax Guide - 2019 - 0Sofiene CharfiNo ratings yet

- Justice and Fairness: Promoting The Common GoodDocument11 pagesJustice and Fairness: Promoting The Common GoodErika Mae Isip50% (2)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Heidenhain EXE 602 E Datasheet 2015617105231Document6 pagesHeidenhain EXE 602 E Datasheet 2015617105231Citi MelonoNo ratings yet

- Critical Examination of Jane Eyre As A BildungsromanDocument4 pagesCritical Examination of Jane Eyre As A BildungsromanPRITAM BHARNo ratings yet

- Comments On Manual Dexterity-NYTDocument78 pagesComments On Manual Dexterity-NYTSao LaoNo ratings yet

- Second Division G.R. No. 212860, March 14, 2018 Republic of The Philippines, Petitioner, V. Florie Grace M. Cote, Respondent. Decision REYES, JR., J.Document6 pagesSecond Division G.R. No. 212860, March 14, 2018 Republic of The Philippines, Petitioner, V. Florie Grace M. Cote, Respondent. Decision REYES, JR., J.cnfhdxNo ratings yet

- Consolidation of Wholly Owned Subsidiaries Aquired at More Than Book ValueDocument39 pagesConsolidation of Wholly Owned Subsidiaries Aquired at More Than Book ValuejuniarNo ratings yet

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Alumni Association Action Plan 2017: Republic of The PhilippinesDocument2 pagesAlumni Association Action Plan 2017: Republic of The PhilippinesLea Cardinez100% (1)

- Elections ESL BritishDocument3 pagesElections ESL BritishRosana Andres DalenogareNo ratings yet

- Food Groups and What They DoDocument26 pagesFood Groups and What They DoCesar FloresNo ratings yet

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)