Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Practice of Architecture.: Aemfdcob GK OM

Uploaded by

reacharunkOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Practice of Architecture.: Aemfdcob GK OM

Uploaded by

reacharunkCopyright:

Available Formats

882 PRACTICE OF

ARCHITECTURE.

Book HI.

size of them : they must not be less than three feet even in small buildings, because, aJ

Sir \Villiam Chambers seriously says,

"

there is not room for a fat

person to pass between

tliem."

'J61f). Before leaving the subject

which has furnished the preceding remarks on mter-

coluinniations, we most earnestly

recommend to the student the rc-jierusal of Section II. of

this Book. The intervals between the columns have, in tliis sectioi., been considered more

with regard to the laws resulting from the

distribution of the subordinate parts, than witb

relation^to the weiglits and supports, which seem to have regulated the ancient practice :

but this distril)ution should not prevent the application generally of the principle, which

may without difficulty, as we know from our own experience, be so brought to bear upon

it as to ])roduce the most satisfactory results. We may be perhaps accused of bringing a

fine art under mechanical laws, and reducing refinement to rules. We regret that we

cannot bind the professor by more stringent regulations. It is certain that, having in this

respect carried the point to its utmost limit, there will still be amjjle opportunity left for

him to snatch that grace, beyond the reach of art, with the neglect whereof the critics are

,wont so much to taunt the artist in every branch.

Sect. X.

ARCADES AND ARCHES.

2617. An arcade, or series of arclies, is perhaps one of the most beautiful objects at-

tached to the buildings of a city which architecture aflbrds. The utility, moreover, o<

arcades in some climates, for shelter from rain and heat, is obvious

;

but in this dark

climate, the inconveniences resulting from the obstruction to light which they otter, seems

to preclude their use in the cities of England. About public buildings, however, where

the want of light is of no importance to the lower story, as

in theatres, courts of law, churches, and places of jjublic amuse-

ment, and in large country seats, their introduction is often

the source of great beauty, when fitly placed.

2618. In a previous section (2524.)

we have spoken of

Lel)run's theory of an equality between the weiglits and sup-

ports in decorative architecture : we shall here return to the

subject, as applied to arcades, though the analogy is not, per-

haps, strictly in point, because of the dissimilarity of an arch to

a straight lintel. In

fi>j.

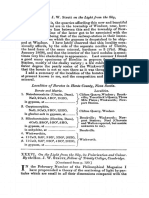

898. the hatched jiart AEMFDCOB

is the load, and ABGH, CDIK the supports. The line GK

is divided into six parts, which serve as a scale to the diagram,

the opening III being four of them, the height BH six, NO

two, and OM one. From the exact quadrature of the circle

being unknown, it is impossible to measure with strict accu-'

racy the surface BOC, which is necessary for finding by sub-

^

" '

traction the surface AEMFDCOB; but using the common

Fig. 898,

method, we have

AD X AE-

'^.^^'^''=

to that surface; or, in figures,

6 X 3

-

-

4

X

4 X -7854

= 11-72.

Now the suports will be IK x IC x 2 (the two piers) = the piers; or, in figures,

1x6x2 = 1200.

That is, in the diagram the load is very nearly equal to the supports, and woidd have been

found quite so, if we could have more accurately measured the circle, or had with greater

nicety constructed it. But we have here, where strict mathematical precision is not our

object, a sufficient ground for the observations which follow, and which, if not founded on

something more than speculation, form a series of very singular accidents. We have chosen

to illustrate the matter by an investigation of the examples of arcades by Vignola, because

we have thought his orders and arcades of a higher finish than those of any other master

;

but testing tlie hypothesis, which we intend to carry out by examples from I'alladio, Sca-

mozzi, and the other great masters of our art, not contemplated by Lebrun, the small

diffirences, instead of throwing a doubt upon, seem to confirm it.

2{jl9. In

Jig.

898. we will now carry, therefore, the consideration of the

weights and

supports a step further than I^ebrun, by comparing them with the void space they sur-

round, that is, the opening HBOCI

;

and here we have the rectangle HBCI = HB x HI,

that is, 6x4

=

24, and the semicircle BOC equal, as above, to

^

=6-28. Tiien

24

+6 -28 = 30

-28 is the area of the whole void, and the weight and support being 11-72 +

You might also like

- Pattern Design - A Book for Students Treating in a Practical Way of the Anatomy - Planning & Evolution of Repeated OrnamentFrom EverandPattern Design - A Book for Students Treating in a Practical Way of the Anatomy - Planning & Evolution of Repeated OrnamentRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (2)

- Mode Minimum May MayDocument1 pageMode Minimum May MayreacharunkNo ratings yet

- Theory: of ArchitectureDocument1 pageTheory: of ArchitecturereacharunkNo ratings yet

- Theory: AuchitfxtuiieDocument1 pageTheory: AuchitfxtuiiereacharunkNo ratings yet

- Orders.: of of of in Englisli Feet. in FeetDocument1 pageOrders.: of of of in Englisli Feet. in FeetreacharunkNo ratings yet

- Llic If ItDocument1 pageLlic If ItreacharunkNo ratings yet

- How To Calculate CatenaryDocument36 pagesHow To Calculate Catenaryatac101100% (2)

- Orders AboveDocument1 pageOrders AbovereacharunkNo ratings yet

- Practice of Architecture.: We MindDocument1 pagePractice of Architecture.: We MindreacharunkNo ratings yet

- When When: FinishDocument1 pageWhen When: FinishreacharunkNo ratings yet

- Theory: of ArchitectureDocument1 pageTheory: of ArchitecturereacharunkNo ratings yet

- '2fi5's. Is, Tlie ItsDocument1 page'2fi5's. Is, Tlie ItsreacharunkNo ratings yet

- Arcades AboveDocument1 pageArcades AbovereacharunkNo ratings yet

- Alaa-92-G439 A One-Equatlon Turbulence For Aerodynamic FlowsDocument23 pagesAlaa-92-G439 A One-Equatlon Turbulence For Aerodynamic FlowsDr. G. C. Vishnu Kumar Assistant Professor III - AERONo ratings yet

- The WhenDocument1 pageThe WhenreacharunkNo ratings yet

- A Treatise of The Properties of Arches and Their Abutment PiersDocument89 pagesA Treatise of The Properties of Arches and Their Abutment Piersjuan manuelNo ratings yet

- Deem Much Xiv. AsDocument1 pageDeem Much Xiv. AsreacharunkNo ratings yet

- Intercolumni: AtionsDocument1 pageIntercolumni: AtionsreacharunkNo ratings yet

- This (Diet Liigher, Line Line: Is TlieDocument1 pageThis (Diet Liigher, Line Line: Is TliereacharunkNo ratings yet

- Scientificamerican08211869 114Document1 pageScientificamerican08211869 114ari sudrajatNo ratings yet

- Carpentry.: ThoughDocument1 pageCarpentry.: ThoughreacharunkNo ratings yet

- Sls Case StudyDocument4 pagesSls Case Studyapi-567341485No ratings yet

- St'ttiiig Is Ol' It Is, TlieDocument1 pageSt'ttiiig Is Ol' It Is, TliereacharunkNo ratings yet

- Hi. ANH and The Many MayDocument1 pageHi. ANH and The Many MayreacharunkNo ratings yet

- Non-Spill Discharge Characteristics of Bucket ElevatorsDocument27 pagesNon-Spill Discharge Characteristics of Bucket ElevatorsKorosh ForoghanNo ratings yet

- En (1040)Document1 pageEn (1040)reacharunkNo ratings yet

- ArticleDocument22 pagesArticlezrxyb7rf66No ratings yet

- Chris Van Den Broeck - Alcubierre's Warp Drive: Problems and ProspectsDocument6 pagesChris Van Den Broeck - Alcubierre's Warp Drive: Problems and ProspectsHerftezNo ratings yet

- Spalart1992 - One Equation ModelDocument23 pagesSpalart1992 - One Equation ModelSsheshan PugazhendhiNo ratings yet

- Sergio Pellegrino University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK: Deployment. The Reverse Transformation Is Called RetractionDocument35 pagesSergio Pellegrino University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK: Deployment. The Reverse Transformation Is Called RetractionRupesh DangolNo ratings yet

- Chris Van Den Broeck - On The (Im) Possibility of Warp BubblesDocument6 pagesChris Van Den Broeck - On The (Im) Possibility of Warp BubblesUtnyuNo ratings yet

- Tlieir Wliolt'Document1 pageTlieir Wliolt'reacharunkNo ratings yet

- A Letter From Sir William R. Hamilton To John T. Graves, EsqDocument7 pagesA Letter From Sir William R. Hamilton To John T. Graves, EsqJoshuaHaimMamouNo ratings yet

- Hjelmslev-Eudoxus' Axiom and Archimedes' Lemma PDFDocument10 pagesHjelmslev-Eudoxus' Axiom and Archimedes' Lemma PDFEdwin PinzónNo ratings yet

- En (1326)Document1 pageEn (1326)reacharunkNo ratings yet

- Strutt 1871Document6 pagesStrutt 1871Erik SilveiraNo ratings yet

- Arcades: ArchesDocument1 pageArcades: ArchesreacharunkNo ratings yet

- Geometry Design and Structural Analysis of Steel Single-Layer Geodesic DomesDocument5 pagesGeometry Design and Structural Analysis of Steel Single-Layer Geodesic DomesAntenasmNo ratings yet

- It, ('.Vitl), Ties Tlie F-Li'jhtcitDocument1 pageIt, ('.Vitl), Ties Tlie F-Li'jhtcitreacharunkNo ratings yet

- Piers: VaultsDocument1 pagePiers: VaultsreacharunkNo ratings yet

- Arches.: ArcadesDocument1 pageArches.: ArcadesreacharunkNo ratings yet

- Otc-6333 - Dedicated Finite Element Model For Analyzing Upheaval Buckling Response of Submarine PipelinesDocument10 pagesOtc-6333 - Dedicated Finite Element Model For Analyzing Upheaval Buckling Response of Submarine PipelinesAdebanjo TomisinNo ratings yet

- De Sitter Vacua in String TheoryDocument12 pagesDe Sitter Vacua in String TheoryJack Ignacio NahmíasNo ratings yet

- International Journal of Solids and Structures Volume 2 Issue 2 1966 (Doi 10.1016/0020-7683 (66) 90018-7) Jacques Heyman - The Stone Skeleton PDFDocument43 pagesInternational Journal of Solids and Structures Volume 2 Issue 2 1966 (Doi 10.1016/0020-7683 (66) 90018-7) Jacques Heyman - The Stone Skeleton PDFManuelPérezNo ratings yet

- International Journal of Solids and Structures Volume 2 Issue 2 1966 (Doi 10.1016/0020-7683 (66) 90018-7) Jacques Heyman - The Stone Skeleton PDFDocument43 pagesInternational Journal of Solids and Structures Volume 2 Issue 2 1966 (Doi 10.1016/0020-7683 (66) 90018-7) Jacques Heyman - The Stone Skeleton PDFManuelPérezNo ratings yet

- Capacitance in PhysicsDocument54 pagesCapacitance in PhysicsMani PillaiNo ratings yet

- The Stone SkeletonDocument43 pagesThe Stone SkeletonNicola Faggion100% (2)

- Draw MakeDocument1 pageDraw MakereacharunkNo ratings yet

- Common: Tlie TlieDocument1 pageCommon: Tlie TliereacharunkNo ratings yet

- Introduction To ShellsDocument14 pagesIntroduction To ShellskatsiboxNo ratings yet

- Arcades: Arches.Document1 pageArcades: Arches.reacharunkNo ratings yet

- Bricklaying And: 'A'illDocument1 pageBricklaying And: 'A'illreacharunkNo ratings yet

- Taylor 1973Document15 pagesTaylor 1973Hamed Vaziri GoudarziNo ratings yet

- Katherine Freese and Douglas Spolyar - Chain Inflation in The Landscape: Bubble Bubble Toil and TroubleDocument30 pagesKatherine Freese and Douglas Spolyar - Chain Inflation in The Landscape: Bubble Bubble Toil and TroubleJomav23No ratings yet

- Box Girder Bridge DesignDocument7 pagesBox Girder Bridge DesignSharath ChandraNo ratings yet

- Malament D., Rotation - No - Go PDFDocument29 pagesMalament D., Rotation - No - Go PDFAndreas ZoupasNo ratings yet

- A Warp Drive' With More Reasonable Total Energy RequirementsDocument9 pagesA Warp Drive' With More Reasonable Total Energy RequirementsCarlos BorrNo ratings yet

- Appendix BDocument37 pagesAppendix BRaed JahshanNo ratings yet

- Project CompletionDocument11 pagesProject CompletionManish KumarNo ratings yet

- BPS Domain Walls From Backreacted Orientifolds: J. BL Ab Ack, B. Janssen, T. Van Riet, B. VercnockeDocument23 pagesBPS Domain Walls From Backreacted Orientifolds: J. BL Ab Ack, B. Janssen, T. Van Riet, B. VercnockecrocoaliNo ratings yet

- Prospekt BGF PDFDocument150 pagesProspekt BGF PDFreacharunkNo ratings yet

- Prospekt BGF PDFDocument150 pagesProspekt BGF PDFreacharunkNo ratings yet

- Supplement To The Prospectuses and Summary Prospectuses For Investor Shares and Admiral™SharesDocument65 pagesSupplement To The Prospectuses and Summary Prospectuses For Investor Shares and Admiral™SharesreacharunkNo ratings yet

- General Terms and Conditions of The Pzu NNW (Personal Accident Insurance Pzu Edukacja InsuranceDocument19 pagesGeneral Terms and Conditions of The Pzu NNW (Personal Accident Insurance Pzu Edukacja InsurancereacharunkNo ratings yet

- Supplement To The Prospectuses and Summary Prospectuses For Investor Shares and Admiral™SharesDocument65 pagesSupplement To The Prospectuses and Summary Prospectuses For Investor Shares and Admiral™SharesreacharunkNo ratings yet

- Prospekt BGF PDFDocument150 pagesProspekt BGF PDFreacharunkNo ratings yet

- Prospekt BGF PDFDocument150 pagesProspekt BGF PDFreacharunkNo ratings yet

- Emergency Response Quick Guide MY: 2014Document2 pagesEmergency Response Quick Guide MY: 2014reacharunkNo ratings yet

- En (1463)Document1 pageEn (1463)reacharunkNo ratings yet

- En (1462)Document1 pageEn (1462)reacharunkNo ratings yet

- NameDocument2 pagesNamereacharunkNo ratings yet

- En (1461)Document1 pageEn (1461)reacharunkNo ratings yet

- En (1464)Document1 pageEn (1464)reacharunkNo ratings yet

- En (1459)Document1 pageEn (1459)reacharunkNo ratings yet

- En (1454)Document1 pageEn (1454)reacharunkNo ratings yet

- En (1460)Document1 pageEn (1460)reacharunkNo ratings yet

- En (1457)Document1 pageEn (1457)reacharunkNo ratings yet

- En (1456)Document1 pageEn (1456)reacharunkNo ratings yet

- En (1450)Document1 pageEn (1450)reacharunkNo ratings yet

- En (1458)Document1 pageEn (1458)reacharunkNo ratings yet

- En (1455)Document1 pageEn (1455)reacharunkNo ratings yet

- En (1452)Document1 pageEn (1452)reacharunkNo ratings yet

- En (1453)Document1 pageEn (1453)reacharunkNo ratings yet

- En (1451)Document1 pageEn (1451)reacharunkNo ratings yet

- En (1390)Document1 pageEn (1390)reacharunkNo ratings yet

- En (1388)Document1 pageEn (1388)reacharunkNo ratings yet

- And Rome.: in Front of The Prostyle Existed atDocument1 pageAnd Rome.: in Front of The Prostyle Existed atreacharunkNo ratings yet

- Mate The: (Fig. - VrouldDocument1 pageMate The: (Fig. - VrouldreacharunkNo ratings yet

- En (1389)Document1 pageEn (1389)reacharunkNo ratings yet

- En (1387)Document1 pageEn (1387)reacharunkNo ratings yet

- CST Math - Functions Part I (Lesson 1)Document27 pagesCST Math - Functions Part I (Lesson 1)api-245317729No ratings yet

- DICE ManualDocument102 pagesDICE ManualMarcela Barrios RiveraNo ratings yet

- Implementation of Resonant Controllers and Filters in Fixed-Point ArithmeticDocument9 pagesImplementation of Resonant Controllers and Filters in Fixed-Point Arithmeticmipanduro7224No ratings yet

- Lesson 4Document2 pagesLesson 4Trisha ConcepcionNo ratings yet

- Digital Sat Math Test 2Document11 pagesDigital Sat Math Test 2nakrit thankanapongNo ratings yet

- Using The PNR Curve To Convert Effort To ScheduleDocument2 pagesUsing The PNR Curve To Convert Effort To ScheduleRajan SainiNo ratings yet

- Son-Control Charts 3BADocument14 pagesSon-Control Charts 3BATHẢO NGUYỄN NGỌCNo ratings yet

- Audit Sampling: Quiz 2Document8 pagesAudit Sampling: Quiz 2weqweqwNo ratings yet

- Matlab - An Introduction To MatlabDocument36 pagesMatlab - An Introduction To MatlabHarsh100% (2)

- Aon Risk Maturity Index Report 041813Document28 pagesAon Risk Maturity Index Report 041813Dewa BumiNo ratings yet

- Concrete Technology (CE205) Concrete Technology Laboratory Report Academic Year (2019-2020)Document10 pagesConcrete Technology (CE205) Concrete Technology Laboratory Report Academic Year (2019-2020)Hawar AhmadNo ratings yet

- FlowVision Brochure 2014 PDFDocument2 pagesFlowVision Brochure 2014 PDFmpk8588No ratings yet

- 3D Grid GenerationDocument5 pages3D Grid Generationsiva_ksrNo ratings yet

- Algebra I U3 AssessmentDocument6 pagesAlgebra I U3 Assessmentapi-405189612No ratings yet

- Alphabet TheoryDocument9 pagesAlphabet TheoryMahendra JayanNo ratings yet

- P436 Lect 13Document20 pagesP436 Lect 13Zhenhua HuangNo ratings yet

- Focus Group Interview TranscriptDocument5 pagesFocus Group Interview Transcriptapi-322622552No ratings yet

- Exercise2 SolDocument7 pagesExercise2 SolKhalil El LejriNo ratings yet

- Kendriya Vidyalaya Sangthan Session Ending Examination Informatics Practice (CLASS XI) Sample Paper MM: 70 TIME:3:00 HRSDocument6 pagesKendriya Vidyalaya Sangthan Session Ending Examination Informatics Practice (CLASS XI) Sample Paper MM: 70 TIME:3:00 HRSkumarpvsNo ratings yet

- Maths SankaraDocument40 pagesMaths SankaraA Vinod KaruvarakundNo ratings yet

- Extra Credit Group8 Jan29Document15 pagesExtra Credit Group8 Jan29Jose VillaroelaNo ratings yet

- Ps 8Document1 pagePs 8Yoni GefenNo ratings yet

- Statics and Mechnics of StructuresDocument511 pagesStatics and Mechnics of StructuresPrabu RengarajanNo ratings yet

- Principles of GIS Study Guide PDFDocument16 pagesPrinciples of GIS Study Guide PDFPaty Osuna FuentesNo ratings yet

- T Distribution and Test of Hypothesis Part I STEMDocument30 pagesT Distribution and Test of Hypothesis Part I STEMnicole quilangNo ratings yet

- 9709 w15 QP 43Document4 pages9709 w15 QP 43yuke kristinaNo ratings yet

- 8 Closed Compass V2docDocument8 pages8 Closed Compass V2docCarlo Miguel MagalitNo ratings yet

- Supportive Maths - Work Sheet For g12Document3 pagesSupportive Maths - Work Sheet For g12Ephrem ChernetNo ratings yet

- Electrical Formulas ExplanationsDocument16 pagesElectrical Formulas ExplanationsJShearer100% (24)

- What Is SQL1Document62 pagesWhat Is SQL1goldybatraNo ratings yet

- A Place of My Own: The Architecture of DaydreamsFrom EverandA Place of My Own: The Architecture of DaydreamsRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (242)

- Architectural Detailing: Function, Constructibility, AestheticsFrom EverandArchitectural Detailing: Function, Constructibility, AestheticsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Dream Sewing Spaces: Design & Organization for Spaces Large & SmallFrom EverandDream Sewing Spaces: Design & Organization for Spaces Large & SmallRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (24)

- Building Structures Illustrated: Patterns, Systems, and DesignFrom EverandBuilding Structures Illustrated: Patterns, Systems, and DesignRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (4)

- The Hotel on Place Vendôme: Life, Death, and Betrayal at the Hotel Ritz in ParisFrom EverandThe Hotel on Place Vendôme: Life, Death, and Betrayal at the Hotel Ritz in ParisRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (49)

- House Rules: How to Decorate for Every Home, Style, and BudgetFrom EverandHouse Rules: How to Decorate for Every Home, Style, and BudgetNo ratings yet

- Martha Stewart's Organizing: The Manual for Bringing Order to Your Life, Home & RoutinesFrom EverandMartha Stewart's Organizing: The Manual for Bringing Order to Your Life, Home & RoutinesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (11)

- The Urban Sketching Handbook: Understanding Perspective: Easy Techniques for Mastering Perspective Drawing on LocationFrom EverandThe Urban Sketching Handbook: Understanding Perspective: Easy Techniques for Mastering Perspective Drawing on LocationRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (12)

- Fundamentals of Building Construction: Materials and MethodsFrom EverandFundamentals of Building Construction: Materials and MethodsRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (3)

- Welcome Home: A Cozy Minimalist Guide to Decorating and Hosting All Year RoundFrom EverandWelcome Home: A Cozy Minimalist Guide to Decorating and Hosting All Year RoundRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (11)

- The Bright Ages: A New History of Medieval EuropeFrom EverandThe Bright Ages: A New History of Medieval EuropeRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- The Florentines: From Dante to Galileo: The Transformation of Western CivilizationFrom EverandThe Florentines: From Dante to Galileo: The Transformation of Western CivilizationRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (11)

- Vastu: The Ultimate Guide to Vastu Shastra and Feng Shui Remedies for Harmonious LivingFrom EverandVastu: The Ultimate Guide to Vastu Shastra and Feng Shui Remedies for Harmonious LivingRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (41)

- Extraordinary Projects for Ordinary People: Do-It-Yourself Ideas from the People Who Actually Do ThemFrom EverandExtraordinary Projects for Ordinary People: Do-It-Yourself Ideas from the People Who Actually Do ThemRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (3)

- How to Create Love, Wealth and Happiness with Feng ShuiFrom EverandHow to Create Love, Wealth and Happiness with Feng ShuiRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- The Pint-Sized Guide to Organizing Your HomeFrom EverandThe Pint-Sized Guide to Organizing Your HomeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (2)

- Problem Seeking: An Architectural Programming PrimerFrom EverandProblem Seeking: An Architectural Programming PrimerRating: 2 out of 5 stars2/5 (1)

- The Year-Round Solar Greenhouse: How to Design and Build a Net-Zero Energy GreenhouseFrom EverandThe Year-Round Solar Greenhouse: How to Design and Build a Net-Zero Energy GreenhouseRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (3)

- Solar Power Demystified: The Beginners Guide To Solar Power, Energy Independence And Lower BillsFrom EverandSolar Power Demystified: The Beginners Guide To Solar Power, Energy Independence And Lower BillsRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (2)

- The Architect's Studio Companion: Rules of Thumb for Preliminary DesignFrom EverandThe Architect's Studio Companion: Rules of Thumb for Preliminary DesignRating: 2 out of 5 stars2/5 (1)

- Big Bim Little Bim: the Practical Approach to Building Information Modeling - Integrated Practice Done the Right Way!From EverandBig Bim Little Bim: the Practical Approach to Building Information Modeling - Integrated Practice Done the Right Way!Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (4)

- Cozy Minimalist Home: More Style, Less StuffFrom EverandCozy Minimalist Home: More Style, Less StuffRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (154)

- Postmodernism: A Very Short IntroductionFrom EverandPostmodernism: A Very Short IntroductionRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (23)

- Site Analysis: Informing Context-Sensitive and Sustainable Site Planning and DesignFrom EverandSite Analysis: Informing Context-Sensitive and Sustainable Site Planning and DesignRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (3)