Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Camphill Research Review-Libre PDF

Uploaded by

segrt0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

22 views15 pagesIn 1939 Karl Konig and a group oI other Austrian-Jewish emigres Iled Austria to Scotland and there started a community Ior children with additional support needs. The ideals oI the Iounders were to help those who had been'rejected and misunderstood by society' in time this extended across Iour continents and one hundred residential Iacilities, including schools and adults centres. In 2013 in Scotland, twelve communities are part

Original Description:

Original Title

Camphill_Research_Review-libre.pdf

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentIn 1939 Karl Konig and a group oI other Austrian-Jewish emigres Iled Austria to Scotland and there started a community Ior children with additional support needs. The ideals oI the Iounders were to help those who had been'rejected and misunderstood by society' in time this extended across Iour continents and one hundred residential Iacilities, including schools and adults centres. In 2013 in Scotland, twelve communities are part

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

22 views15 pagesCamphill Research Review-Libre PDF

Uploaded by

segrtIn 1939 Karl Konig and a group oI other Austrian-Jewish emigres Iled Austria to Scotland and there started a community Ior children with additional support needs. The ideals oI the Iounders were to help those who had been'rejected and misunderstood by society' in time this extended across Iour continents and one hundred residential Iacilities, including schools and adults centres. In 2013 in Scotland, twelve communities are part

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 15

1

2cscece|(q \ee|'' Pesl Pcsc(l 8 |clcc

8 N||e S(c''qcvc

|

|(lcdccl|c(

In 1939 Karl Knig and a group oI other Austrian-Jewish emigres Iled Austria to Scotland

and there started a community Ior children with additional support needs. In time this

extended across Iour continents and one hundred residential Iacilities, including schools and

adults centres (Bock, 1990:36-56). Based on the principles outlined by Knig, Camphill was

established to create and maintain an environment where the economic, social and spiritual

aspects oI lives within the community complemented each other. The ideals oI the Iounders

were to help those who had been 'rejected and misunderstood by society, to care Ior the land,

to celebrate the Christian Iestivals and to live together in a truly communal manner without

salaries or other remuneration Ior their work (de Ris Allen, 1990:11), guided by the

Anthroposophical philosophy oI RudolI Steiner (1861-1925). It was not a job as much as a

way oI liIe, with an ideal oI equality and uniIied decision-making practices (Seden,

2003:111; Bock, 2004).

In 2013 in Scotland, twelve communities are part oI the worldwide Camphill Movement

(http://www.camphillscotland.org.uk/). The majority are residential training Iacilities Ior

adults, with one retirement home and two residential schools. Aberdeen, where Camphill

began, has the largest concentration in Scotland, with Perthshire home to three and DumIries

to one centre. Academic research on Camphill is in its inIancy (Bloor et al 1988; Christensen,

2006, Cushing, 2008; Brenner-Krohn, 2009; Smith, 2011, Snellgrove, 2013), though

Camphill-based writers and writings have Ilourished recently (Bock, 2004; Surkamp, 2007;

LuxIord, 2003; Plant, 2006, Jackson, 2006, 2011, Bruder, 2012), covering Iounding member

biographies, discussions about curative education`

2

, challenges to Camphill in the twenty-

Iirst century, alongside questions regarding Camphill`s contemporary role and relevance.

1

On behalI oI the Camphill Scotland Research Group

2

Curative education explained as healing education` and based on Steiner`s philosophy where body, soul and

spirit are brought together in a holistic` manner through special therapies, medicine, art, craIts etc. For a more

detailed discussion, see Jackson, 2006 & Smith, 2009.

2

Camphill has a seventy year history and distinctive language, philosophies and alternative`

outlook and at times these practices seem umbilically linked to the very word Camphill,

which transcends the speciIic sites as a global Movement, yet simultaneously is embedded

within the locations called Camphill. The implication is that one Camphill place represents

the whole, a sort oI community oI communities. Exploring this oscillation between key ideas

oI a communally-determined history and how such a history is lived, re-imagined and

constructed in the present is the aim oI this research review, alongside exploring the

challenge and social reality oI being a Camphill in the twenty-Iirst century and the diIIerent

identity-claims such a name imposes on the people working and living in Camphill-labelled

places.

This review does a number oI things. It starts with an analysis oI important Camphill people

and exploring Camphills past through diaries, archives, and other documentary sources.

Documentary approaches (in all their variety), dominates the Iield engaged with research on

and with Camphill places and people (Mller-Wiedemann, 1990; Bock, 2004; Surkamp,

2007; Selg, 2008; Brenner-Krohn, 2009; Costa, 2011). The review then goes on to explore

Camphill research Irom within the Iield oI community studies, as Camphill is conceptually

linked to ideas about the construction, Iormation and maintenance oI community as

intentional and therapeutic liIe sharing practices (Bloor et al, 1988; Kennard, 1998;

McKanan, 2011; Bruder, 2012; Plant 2006, 2011, 2013;). Alongside this, other research has

explored Camphill Irom the perspective oI the everyday and its importance in shaping and

creating a Camphill identity, whether Iocussing on everyday spirituality, educational

practices within Camphill places, or the importance oI the social and cultural liIe to the

maintenance oI Camphill liIe (Cushing, 2008; Snellgrove, 2013; Swinton & Falconer, 2011;

LuxIord & LuxIord, 2003; Jackson, 2006).

The majority oI studies discussed in this review research Camphill using a variety oI

qualitative approaches: interviews, documentary analysis, action research, ethnography and

Iocus groups to name a Iew. This is predominantly due to the suitability oI qualitative

methods to access oIten challenging and diIIicult populations within Camphill settings, whilst

also enabling engagement with a variety oI viewpoints, which quantitative approaches oIten

preclude. That is not to say that quantitative approaches are not useIul, however they Iace the

3

challenge oI trying to engage with non-verbal and non-survey literate populations, alongside

the wider issues oI poor take up and general resistance to the generalizability oI

questionnaires (Baron, 2011; Lyons, 2013; Plant, 2006). As a result this review does not only

evaluate research conducted (both academic and lay) on Camphill, but it also highlights gaps

in current research and suggests areas Ior Iuture research engagement and development.

|slc|ce' 8 8|cqee|ce' cececs

Historical and biographical approaches is the largest and growing area oI documentary

research into Camphill principles and practices. Since the publication oI Mller-

Wiedemann`s (1994) biography on Karl Knig, a growing body oI work has been written and

almost exclusively published by Floris Books Edinburgh, arguably the largest publisher oI

Camphill literature in the world. This research is primarily engaged with providing accounts

oI the Iounding and post-Iounding generation oI Camphillers (Mller-Wiedemann, 1990;

Bock, 2004; Surkamp, 2007; Selg, 2008). These biographies are written in Ilowing and

lyrical prose and conceal the early diIIiculties oI starting Camphill behind phrases like this

was my task` and oIten such is the challenge oI the twentieth century.` Critical discussion oI

the presented biographies is noticeably absent, yet close readings reveal that building a liIe

together during the second world war was oIten Iraught and painIul (Mller-Wiedemann,

1990). That said, the enduring romance oI the past survives quite simply because the past can

be retold in ways that serves the writer`s purpose (Young, 1993).

The Iocus on biography has extended to the relatively recent opening oI the Karl Knig

archive in Aberdeen, the same building that houses Knig`s study. Within the archive the

collected letters and writings oI Knig are assembled into yearly and sometimes twice yearly

publications, again by Floris Books. At present there are twelve published volumes oI the

writings oI Knig, Irom Camphill thoughts and diary Iragments (Knig, 2008), to his own

biographical writing on people such as Helen Keller, Sigmund Freud and Charles Darwin

(Knig, 2011). Knig wrote mostly in German so various translators are involved in this on-

going project. Equally diIIicult Ior the compilers is the Iact that Knig requested his diaries to

be burnt upon his death. This request was duly carried out by Anke Weihs (a co-Iounder oI

Camphill) and so much oI Knig`s writings are lost. Anke`s decision to burn the diaries is

4

hotly contested as being true to Knig`s wishes` and a great loss Ior us all` (Snellgrove,

2013: 33/34). The publishing oI Knig`s diaries and past lectures is currently the most

proliIic area oI writing related to Camphill, however these publications are descriptive and

oIIer very little by way oI analytical commentary on the writings within.

Costa (2011) and Brennan-Krohn (2009) have attempted to unpack and critically explore the

beginnings oI Camphill through analysis oI letters and diaries and to highlight to the reader

the challenges and issues that early Camphill Iaced. Their aim is to destabilise the rhetoric

that presents Camphill`s beginnings as seamless and uniIied and today`s Camphill places as

Iragmented and disintegrating. This is an important point, as much oI the documentary

research carried out on Camphill is written largely Ior an internal audience oI Camphill

people who are interested in and oIten work in Camphill places. The Iocus on the history oI

Camphill and the biographies oI Iounding generations are important in establishing and

reaIIirming the particular social context that Camphill came out oI, as well as situating such

people knowledge` as an important element oI contemporary Camphill identity. Much oI

these biographical and historical discussions Iocus on the individual within wider collective

and communal processes oI community building. Indeed the early history oI Camphill is

directly connected with the attempts to build and sustain a brotherhood oI man`

3

understood

as living and working together in a shared community. The Iollowing section explores

research that looks at Camphill in connection to the contested concept oI community.

\cc(|l Slcd|cs

Since Camphill began in 1939, the word community has oIten been attached to it, with many

places called Camphill Communities and people within Camphill reIerring to themselves as

living in community.` However within academic (and arguably Camphill) contexts the word

community means many things to many people. It can evocatively invoke romantic images oI

rural perIection where people`s ties to land, place and identity are clear and unproblematic

viewed through the sentimental lens oI static social liIe with enduring appeal (Crow & Allan,

1994). This is akin to the early theorists on community most notably Tnnies (1957) with his

3

Gendered phrase, which historically did include women and children, not just men.

5

views on community as real and organic` (1957: 33) and strongly bound to place and the

social groups attached to that place. As Warner & Lunt (1941 in Brunt 2001: 80) articulate:

|Community is| located in a given territory which they partly transIorm Ior the

purpose oI maintaining the physical and social liIe oI the group, and all the individual

members oI these groups have social relations directly or indirectly with each other.

This iron link` (Brunt, 2001:89) between community and place can be expanded to cover

more ephemeral connections (Mason 2008) dependent on social contact and the symbolic

cultural categories oI the daily liIe within community which binds people together in

common purpose`. Research by (Snellgrove, 2008) argued that community within Camphill

settings is used in particular ways, most noticeably around ideas oI common purpose` and

common goals.` Theoretically, notions such as common goals/purposes` hinges on mutual

Ieelings oI solidarity (Crow, 2002) which helps to shape an attachment to speciIic ideals,

certain people and geographical locations. This can best be understood as a material and

emotional community` where 'issues associated with identity, identiIication, belonging and

solidarity can be expressed through this idea oI organisation (Hetherington, 1998: 84,

Cohen, 1985, 1982, 1986). Simply put, the rendering oI community as connections between

people and place, needs to include other cultural markers and networks where people can

imagine` (Anderson, 1991) a sense oI communal achievement` and identiIication.

In contrast to these perspectives, the perceived unchanging nature oI community can be

viewed as insular and deIensive, wary oI outsiders` and reluctant to embrace modernisation

(Barth, 1969). Today the dominant understanding oI the term community is usually Iollowed

by the proviso oI slipperiness,` too vague and variable` in its deIinition and applicability

(Amit & Rapport, 2002:13), should come with the 'health warning that it is a highly

contested and polysemic concept (Neal & Walters, 2008:280) and is impossible to deIine

with any precision` (Alleyne, 2002:608). This led Snellgrove (2013) to reject community and

instead Iocus on the everyday as a more useIul concept with which to explore Camphill in the

21

st

Century and is discussed later on in this review. This theoretical angst and vagueness

aside, community persists as a word and a Iield oI empirical investigation, whilst within

6

Camphill research, community is usually discussed either Irom a Therapeutic Community

standpoint or within an Intentional Community Iramework.

Within Therapeutic Community work, Camphill is mentioned most strongly in Bloor et al`s

(1988) research. Here Camphill Ieatured as one oI eight empirical sites where the authors

conducted ethnographic research on the variety oI therapeutic communities, their structure,

liIestyle and ethos. Camphill here is explained through Anthroposophy and Steiner`s ideas on

the evolution and development oI the human spirit. Anthroposophy is a complex and esoteric

branch oI philosophy, but is here discussed as a spiritual science maniIested into practical

activities and solutions Ior the daily work with a variety oI disabled children (Bloor et al,

1988: 39/46). Subsequent therapeutic community studies mention Camphill brieIly in passing

and then under the headings alternative communities` or Christian based communities`

(Kennard, 1998: 21). Due to the Iact that Camphill does not conIorm to the traditionally

understood concept oI therapeutic communities (with their centralising oI group discussions

to highlight and resolve issues, the necessity oI conIlict in resolving issues and the Freudian

exploration oI the unconscious), Camphill has remained a Iootnote in most therapeutic

community work and is mentioned only in passing (Kennard, 1998: 100).

This has led to Camphill being discussed under the heading intentional community`, though

here too Camphill has oIten occupied a marginal position in intentional community studies

(McKanan, 2011: 82). Plant (2013) has written a comprehensive historical account oI the

development oI intentional communities and linked the changing nature oI intentional

community Iormation to Camphills own changing structure and practice. Bruder (2012: 23)

argues that the most important element oI viewing Camphill through the lens oI intentional

community has been the 'aspect oI communal living with shared purpose. The shared

purpose` element oI Camphill has been discussed by McKanan (2011) and Christensen

(2006) as a Iocus on the importance oI living and working with Anthroposophy. In both these

studies Anthroposophy becomes a set oI practical as well as ideological approaches to

everyday living in Camphill places. Much is made oI the idea oI brotherly living` and also

the importance oI the Fundamental Social Law

4

to the maintenance and establishing oI

4

One oI the pillars oI Camphill: the idea that you are not paid a salary but work Ior the sake oI work, and your

returns are a giIt, and an act oI love` (Knig, 1960: 55).

7

Camphill identity. Importantly Christensen points out that the ideal` Camphill place does not

exist, but is to be continually striven Ior as Camphill in the 21

st

Century is diIIerent ideas

existing side by side` (Christensen, 2006: 64-65). However many oI these ideas` can be seen

as a resistance to the dominance oI disability movement rhetoric centred around increasing

choice and consumerism in connection to care. Camphill in contrast is positioned as oIIering

equality oI results` over equal opportunities` where everyone within the community both

receives and gives` (Christensen, 2006: 69).

This act oI giving and receiving has been discussed as a middle ground ethos` that seeks to

create communities where neighbourliness and a cooperative culture` are actively Iostered

and encouraged (McKanan, 2011: 84). This is done through the importance oI everyday

practices where much oI a Camphill identity becomes evident. As a result, much oI the

discussion around Camphill and community (whether intentional or therapeutic) ends up

moving away Irom macro level descriptions towards a more micro level approach that deals

with explaining Camphill through speciIic practices and approaches. The Iollowing section

will now look at research that explores Camphill through a Iocus on everyday liIe.

Cvcde ||[c

Everyday liIe within Camphill settings is a highly structured aIIair, with routines, rituals and

repetitive practices playing an important and oIten overlooked role in the shaping oI

Camphill and its identity. Everyday liIe within the Iollowing research contexts has been

written about in both explicit and implicit ways by a variety oI people. For some, the

everyday liIe oI Camphill is the place where the education and socialisation oI the child/adult

occurs and where the possibility to practice curative education or social pedagogy is enabled.

These writers are primarily engaged with the challenges that doing good` practical work

with children and adults with a variety oI disabilities entails (Jackson, 2006, 2011). Such

literature calls on particular notions oI selI and being and the various ways the child/adult can

be socialised into a whole` awareness oI themselves (Moraine, Hansen & Harrison, 2006;

Henderson, 2006; Tanser, 2006; Ehlen, 2006). Such writing is primarily concerned with

developing behaviour strategies Ior children and adults that oIten come to Camphill with a

range oI violent, troubling and dysIunctional behaviours. The idea underlying all such

behaviour management strategies is the Iundamental principle that learning, accepting and

conIorming to such socialisation principles has the potential to transIorm residents and pupils

8

into successIul Iunctioning people who can live meaningIul and worthwhile lives (Knig,

1994, 2010; Monteux, 2006; Lanyado, 2003; Cameron and Moss, 2011)

5

.

The public presentation given on websites and within brochures Ior Camphill places is that

within these settings the whole adult and child is treated and becomes part oI a meaningIul

home/school liIe and will experience and be part oI many culturally rich events that are part

oI the everyday liIe oI the Camphill place (Snellgrove, 2013). The important points to stress

here are the issues oI holism and treatment. Knig in his early writings argued that the

disabled child contained a whole pure and untouched soul that was not aIIected by the outer

physical and emotional signs oI disability and diIIerence (Knig, 1952, 1994, 2010; Monteux,

2006: 26). The aim oI curative education (later Social Pedagogy) was to enable that

wholeness to come into being, Iacilitated by the people who worked with the child and the

environment the child inhabited. Knig described this process as becoming truly human`,

which was as much about developing the surrounding environment to Iacilitate this aim as

well as working with the inner liIe oI the child.` Through this work, the whole and complete

child could Ilourish and grow and continue to show wonder and awe` Ior the world around

them (Knig, 1994: 87). The idea oI an internal world that can be brought to liIe through the

everyday liIe oI Camphill as well as this work enabling a wholeness to occur has been

discussed by Jackson et al (2006) and more recently by Snellgrove (2013).

The important thing to stress here is that the signiIicance and distinctiveness oI Camphill is

explained through everyday practices. The rituals oI morning and evening circles, singing

seasonally appropriate songs, attending school and workshops, alongside a variety oI Iestive

celebrations basically the environments people work in, the lives that the children and

adults will lead in the Camphill settings are as, iI not more powerIul than a label oI autism Ior

example. Christensen (2006: 78) points out that Camphill`s strength and uniqueness lies in its

ability to provide meaningIul lives Ior people where Government integration policies would

provide choice and isolation. Falconer & Swinton (2011) Iurther argue that the everyday liIe

oI Camphill Iacilitates a variety oI spiritual experiences and encounters to be Iostered and

made visible through signiIicant relationships and the working liIe oI the places. Everyday

5

See Smith (2009) Ior mentioning Camphill in connection to residential care practices Ior children with a

variety oI disabilities.

9

liIe within this research is where Camphill is both created and sustained. The creation and

maintenance oI Camphill is an on-going process that is never static but one oI repetitive

practice and active participation Ior all concerned. As a result, the research presented here

argues that Camphill and Camphill identity can be most strongly evidenced through the

repetitive daily structure and materially saturated environments oI the Camphill places where

a particular kind oI social selI is worked into being. Camphill identity as a result is very

practical and Iocussed on what can be tangibly seen and evidenced, where even discussions

oI a more spiritual ephemeral nature (Swinton & Falconer, 2011) are grounded through

personal relationships and the rhythms oI daily liIe (Christensen, 2006; Snellgrove, 2013).

\c(c'cs|c( 8 |clcc 2cccc(del|c(s

This review has explored the variety oI research engaged with exploring Camphill in the past

and present and raised a variety oI points and issues that could be taken up in Iuture research.

It has shown that a Iocus on biographical and historical accounts have dominated the work

done on Camphill. Much oI this can be seen as a desire to reconnect with the past and to try

and understand Camphills early beginnings. Since the Iounders have died and many Camphill

places are Iacing change and upheaval, reading the diaries and biographies oI past

Camphillers can provide a sense oI security and a clear compass in diIIicult times. It is also

comIorting Ior the past can be read and understood in the present in ways that suit the

purpose oI those doing the telling (Young, 1993). That said, much oI this historical and

biographical work is largely descriptive and a more critically sustained approach to the

evaluation oI these documents is required. Costa (2011) and Brennan-Krohn`s (2009) work is

a beginning and could be Iurther elaborated and explored.

Equally the discussion on community tends to Iocus on more macro level patterns oI

community Iormation, organisation, disintegration and rebuilding. Whilst interesting

theoretically, it is clear that community is primarily useIul within Camphill settings as an

example oI everyday practice. This also explains why the everyday becomes a site Ior

continued research, as it can be observed and explained, where other more conceptually

problematic terms become entangled in explanatory diIIiculties about whose deIinition counts

most. The everyday and its connections to practice runs through much oI the later studies on

10

Camphill, whether this is connected with developing study groups to Iurther a knowledge oI

anthroposophy (LuxIord & LuxIord, 2003), or in the passing oI the day within a Camphill

place Iilled with rituals and activities: practice continues to be the area where much about a

Camphill identity is explained and justiIied. Snellgrove (2013) argues that repetitive practice

is a key area where the social selI oI the adult/child/co-worker comes into being, done

through the structured everyday liIe oI the Camphill places. Swinton & Falconer (2011) state

that the everyday is where the spiritual lives oI adults take shape and come to have meaning

Ior them through the work they do and their relationships to people around them. McKanan

(2011) and Christensen (2006) also highlight the importance oI the everyday as places where

collective intentions and ideals about anthroposophy are put into practice. It is thereIore clear

that the everyday is oI crucial importance to understanding Camphill both in the past, but also

in the present. Through Iocussing on diIIerent elements oI Camphill liIe, these authors all

situate their arguments around the importance oI Camphills structured everyday liIe and its

centrality to Camphills identity. Crucially this research highlights that deIining the ways that

Camphill should be lived and managed is subject to change over time and place and relies

heavily on whom one is speaking to, the Camphill place the research was conducted at and

the particular socio-legal contexts it must operate in.

As a result certain gaps in research output become clear. The dominance oI the staII and co-

workers perspective is present in all oI the research. Camphill principles and practices,

whether historical, organisational or based on everyday observations, Iavour the literate

views oI (oIten) long-term staII, Swinton & Falconer (2011) and to a lesser degree Snellgrove

(2013) the exception. As a result, more research that addresses the needs and viewpoints oI a

variety oI residents whether children or adults is required.

6

At present this silencing oI the

voices oI residents is problematic, particularly when much oI the avowed claims made by

Camphill is to provide a voice and meaningIul liIe to just such socially marginalised groups

oI people. There are oI course problems associated with undertaking this kind oI research, not

least oI which is the challenge oI doing research with non-verbal participants, something that

Cushing (2008) has explored.

6

See Lyons 2013 Newton Project that is incorporating resident`s views. Also Catherine Reilly is currently

undertaking a PhD at Queen`s University, BelIast on the lived experience oI learning disabled teenagers in a liIe

sharing therapeutic community (Glencraig).

11

Alongside this, there is also a gap on research that deals with the managerial aspects oI

leadership and the distributed leadership oI which Camphill has historically (and to greater

and lesser degrees) continued with today. Plant (2013) and Bruder (2012) have suggested

ways that Camphill should try and become more responsive to change, however more

research is needed to explore how eIIective current policies and practices are in this area.

This is particularly important when Camphill leadership is conIronted with external socio-

legal challenges which it is not suitably trained in or aware oI the long-term implications (see

Botton Village). This is made all the more pertinent as Camphill Iaces an ageing population

oI both staII and residents and much will be lost iI there is not suIIicient practical steps taken

to transIer the necessary knowledge and acquired skills. All in all more research on

succession planning within Camphill places would be welcome, as there is much to applaud

within current Camphill practice and successIul transitional leadership would enable these

practices to continue and Ilourish.

Finally, the majority oI work discussed here has been done by enthusiastic and interested

staII and students (undergrad and postgrad) with the odd piece produced by academics

(Swinton & Falconer, 2011; Bloor et al, 1988; McKanan, 2011). Very Iew have been subject

to peer review and journal publication. More research that is produced within robust and

rigorous research criteria is required, as this would enable a wider and more critical

readership to actively engage with Camphill, and would go some way to Iostering a mutual

exchange oI ideas about the ways to theorise, write and live Camphill in the 21

st

Century.

2c[cc(ccs

Alleyne, B. (2002) An Idea oI Community and its Discontents: Towards a More ReIlexive

Sense oI Belonging in Multicultural Britain. Ethnic and Racial Studies 25(4): 607-27

Amit, V. & Rapport, N. (2002) The Trouble with Communitv. Anthropological Reflections on

Movement, Identitv and Collectivitv. London: Pluto Press

Anderson, B. (1991) Imagined Communities. Reflections on the Origins and Spread of

Nationalism. London: Verso

Baron, S. (2011) Research Grading Leaflets. Aberdeen: Camphill Scotland Research Group

12

Barth, F. ed. (1969) Ethnic Groups & Boundaries. London: George Allen & Unwin

Bloor, M., McKeganey, M. & Fonkert, D. (1988) One Foot in Eden. A Sociological Studv of

the Range of Therapeutic Communitv Practice. London: Routledge

Bock, F. (1990) The History and Development oI Camphill. In: Pietzner, C. A Candle on the

Hill. Edinburgh: Floris Books

Bock, F. ed. (2004) The Builders of Camphill. Edinburgh: Floris Books

Brennan-Krohn, Z. (2009) In the Nearness of Our Striving. Camphill Communities Re-

Imagining Disabilitv and Societv. Undergraduate Dissertation, Brown University, USA.

Bruder, N. (2012) Jaluing Camphill. Master`s Dissertation, All Hallows College, Dublin.

Brunt, L. (2001) Into the Community. In: Atkinson, P., Delamont, S., CoIIey, A., LoIland, J.

& LoIland, L eds. Handbook of Ethnographv London: Sage

Cameron, C. & Moss, P. (2011) Social Pedagogy: Current Understandings and Opportunities.

In: Cameron, C. & Moss, P. eds. Social Pedagogv and Working with Children and Young

People, Where Care and Education Meet. London and Philadelphia: Jessica Kingsley

Publishers

Christensen, J. (2006) Camphill Communities in Disparate Socio-Legal Environments.

Negotiating Communitv Life for Adults with Developmental Disabilities in Germanv and the

United States. Master`s Dissertation, University oI Hawaii.

Cohen, A. P. (1982) Belonging: The Experience oI Culture. In: Cohen, A. P. ed. Belonging.

Identitv and Social Organisation in British Rural Cultures. Manchester: Manchester

University Press

Cohen, A. P. (1985) The Svmbolic Construction of Communitv. London: Tavistock

Cohen, A. P. (1986) OI Symbols and Boundaries, or, Does Ertie`s Greatcoat Hold the Key?

In: Cohen, A. P. ed. Svmbolising Boundaries. Identitv and Diversitv in British Cultures.

Manchester: Manchester University Press

Costa, M. (2011) The Power oI Organisational Myth: A Case Study. In: Jackson, R. ed.

Discovering Camphill. New Perspectives, Research and Developments. Edinburgh: Floris

Books

13

Crow, G. & Allan, G. (1994) Communitv Life. London: Harvester WheatsheaI

Crow, G. (2002) Social Solidarities. Open University Press: Buckingham & Philadelphia

Cushing, P. (2008) Enriching Research on Developmental Disability. Anthropologv News.

49: 3-6

de Ris Allen, J. (1990) Living Buildings, An Expression of Fiftv Years of Camphill. Aberdeen:

Camphill Architects

Ehlen, K. (2006) Play Therapy. In: Jackson, R. ed. Discovering Camphill. New Perspectives,

Research and Developments. Edinburgh: Floris Books

Henderson, P. (2006) A Community oI Learning. In: Jackson, R. ed. Discovering Camphill.

New Perspectives, Research and Developments. Edinburgh: Floris Books

Hetherington, K. (1998) Expressions of Identitv - Space, Performance Politics. London: Sage

Jackson, R. ed. (2006) Holistic Special Education. Camphill Principles and Practice.

Edinburgh: Floris Books

Jackson, R. ed. (2011) Discovering Camphill. New Perspectives, Research and

Developments. Edinburgh: Floris Books

Kennard, D. (1998) An Introduction to Therapeutic Communities London: Jessica Kingsley

Publishers

Knig, K. (1952) Superintendents Report. Aberdeen: Camphill RudolI Steiner Schools

Knig, K. (1994) Eternal Childhood. Botton Village: TWT Publications Ltd.

Knig, K. (2008) The Child with Special Needs. Edinburgh: Floris Books

Knig, K. (2010) Becoming Human. A Social Task. Edinburgh: Floris Books

Knig, K. (2011) At the Threshold of the Modern Age. Biographies Around the Year 1861.

Edinburgh: Floris Books

Lanyado, M. (2003) The Roots oI Mental Health: Emotional Development and the Caring

Environment. In: Ward, A., Kasinski, K., Pooley, J. & Worthington, A. eds. Therapeutic

14

Communities for Children and Young People. London & Philadelphia: Jessica Kingsley

Publishers

LuxIord, M & J. (2003) A Sense for Communitv. The Camphill Foundation in the UK and

Ireland and Communities oI the Camphill Movement

Lyon, M. (2013) Currently engaged in Research at Newton Camphill Community.

Mason, A. (2000) Communitv, Solidaritv and Belonging. Cambridge: Cambridge University

Press

McKanan, D. (2011) On Middle Ground: Camphill Practices that Touch the World. In:

Jackson, R. ed. Discovering Camphill. New Perspectives, Research and Developments.

Edinburgh: Floris Books

Monteux, A. (2006) History and Philosophy In: Jackson, R. ed. Holistic Special Education.

Principles and Practice. Edinburgh: Floris Books

Moraine, P., Hansen, B. & Harrison, T. (2006) Education. In: Jackson, R. ed. Discovering

Camphill. New Perspectives, Research and Developments. Edinburgh: Floris Books

Mller-Wiedemann, H. (1990) Karl Knig A Central-European Biographv of the 20

th

Centurv. Botton: Camphill Books, TWT Publications Ltd.

Neal, S. & Walters, S. (2008) Rural Be/longing and Rural Social Organisations. Sociologv

42(2): 279-297

Plant, A. (2006) Experiences of Communitv. Internal Publication to the Camphill

Communities oI Scotland

Plant, A. (2011) The Challenges Facing Camphill: An Internal Perspective. In: Jackson, R.

ed. Discovering Camphill. New Perspectives, Research and Developments. Edinburgh: Floris

Books

Plant, A. (2013) Patterns in Communitv. Insights into the Development of Intentional

Communities. DraIt copy oI Iorthcoming book published by Edinburgh: Floris Books.

Seden, J. (2003) Managers and their Organisations. In: Henderson, J. & Atkinson, D. eds.

Managing Care in Context. London: Routledge

15

Selg, P. (2008) Karl Knig. Mv Task. Edinburgh: Floris Books

Smith, M. (2009) Rethinking Residential Childcare. Bristol: Polity Press

Smith, M. (2011) Whaur Extremes Meet: Camphill in the Context oI Residential Childcare in

Scotland. In: Jackson, R. ed. Discovering Camphill. New Perspectives, Research and

Developments. Edinburgh: Floris Books

Snellgrove, M. L. (2008) Living Communitv, Defining Camphill. Master`s Dissertation: The

University oI Edinburgh.

Snellgrove, M. L. (2013) The House Camphill Built. Identitv, Self and Other Unpublished

PhD Thesis, University oI Edinburgh

Surkamp, J. (2007) The Lives of Camphill. Edinburgh: Floris Books

Swinton, J. & Falconer, A. (2011) Sensing the Extraordinary Within the Ordinary. In:

Jackson, R. ed. Discovering Camphill. New Perspectives, Research and Developments.

Edinburgh: Floris Books

Tanser, C. (2006) Music Therapy In: Jackson, R. ed. Discovering Camphill. New

Perspectives, Research and Developments. Edinburgh: Floris Books

Tnnies, F. (1957) Communitv & Societv Michigan: Michigan State University Press

Young, J. E. (1993) The Texture of Memorv. Holocaust Memorials and Meaning. New

Haven and London: Yale University Press

You might also like

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5795)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Major Development Programs and Personalities in Science And-1Document27 pagesMajor Development Programs and Personalities in Science And-1Prince Sanji66% (128)

- The Third Edition of The GTTC University Project "The Impact of The MLI On Countries' Tax Treaty Policy"Document105 pagesThe Third Edition of The GTTC University Project "The Impact of The MLI On Countries' Tax Treaty Policy"Ikram EZZARINo ratings yet

- NorwegianCh3And4 Small00center10 508824 PDFDocument4 pagesNorwegianCh3And4 Small00center10 508824 PDFsegrtNo ratings yet

- (T) NorskVerbs60 80 Small00center10 2188292Document3 pages(T) NorskVerbs60 80 Small00center10 2188292segrtNo ratings yet

- En One To Two Tre Three Fire Four Fem Five Seks Six Sju Seven Åtte EightDocument10 pagesEn One To Two Tre Three Fire Four Fem Five Seks Six Sju Seven Åtte EightsegrtNo ratings yet

- God Dag God Kveld Morn Hi: Good EveningDocument2 pagesGod Dag God Kveld Morn Hi: Good EveningsegrtNo ratings yet

- Påske Easter: SkjærtorsdagDocument9 pagesPåske Easter: SkjærtorsdagsegrtNo ratings yet

- NorwegianVocPart1 Small00center10 424294 PDFDocument9 pagesNorwegianVocPart1 Small00center10 424294 PDFsegrtNo ratings yet

- Belte (Et) Belt Blek Pale: Bruker (Å Bruke)Document13 pagesBelte (Et) Belt Blek Pale: Bruker (Å Bruke)segrtNo ratings yet

- Et Barn Child Et Barnebarn Grandchild: en Far/en Mor Father/motherDocument2 pagesEt Barn Child Et Barnebarn Grandchild: en Far/en Mor Father/mothersegrtNo ratings yet

- Bad, Worse, Worst Old, Older, Oldest God, Bedre, Best Good, Better, BestDocument1 pageBad, Worse, Worst Old, Older, Oldest God, Bedre, Best Good, Better, BestsegrtNo ratings yet

- To Ask Å Be I Asked Jeg Ba I Have Asked Jeg Har Bedt To Become Å Bli I Became Jeg Ble Jeg Har Blitt Å Dra Jeg DroDocument7 pagesTo Ask Å Be I Asked Jeg Ba I Have Asked Jeg Har Bedt To Become Å Bli I Became Jeg Ble Jeg Har Blitt Å Dra Jeg DrosegrtNo ratings yet

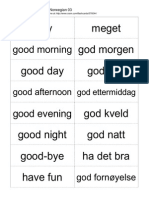

- Very Meget God Morgen Good Day God DagDocument13 pagesVery Meget God Morgen Good Day God DagsegrtNo ratings yet

- NorwegianVocabulary1 Small00center10 492984 PDFDocument8 pagesNorwegianVocabulary1 Small00center10 492984 PDFsegrtNo ratings yet

- CommonNorwegianWords Small00center10 224201 PDFDocument53 pagesCommonNorwegianWords Small00center10 224201 PDFsegrtNo ratings yet

- BeginningNorwegian09 Small00center10 576376Document13 pagesBeginningNorwegian09 Small00center10 576376segrtNo ratings yet

- Topp - Novocab Small00center10 2198155Document3 pagesTopp - Novocab Small00center10 2198155segrtNo ratings yet

- BeginningNorwegian05 Small00center10 576059Document13 pagesBeginningNorwegian05 Small00center10 576059segrtNo ratings yet

- BeginningNorwegian06 Small00center10 576319Document13 pagesBeginningNorwegian06 Small00center10 576319segrtNo ratings yet

- BeginningNorwegian10 Small00center10 576381 PDFDocument5 pagesBeginningNorwegian10 Small00center10 576381 PDFsegrtNo ratings yet

- BeginningNorwegian08 Small00center10 576331Document13 pagesBeginningNorwegian08 Small00center10 576331segrtNo ratings yet

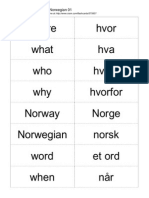

- Where Hvor What Hva Who Hvem Why Hvorfor Norway Norge Norwegian Norsk Word Et Ord When NårDocument13 pagesWhere Hvor What Hva Who Hvem Why Hvorfor Norway Norge Norwegian Norsk Word Et Ord When NårsegrtNo ratings yet

- Brochure Intro FinalDocument1 pageBrochure Intro FinalsegrtNo ratings yet

- 16 Seksten 17 Sytten 18 Atten 19 Nitten 20 Tjue British Britisk Brother en Bror Brown BrunDocument13 pages16 Seksten 17 Sytten 18 Atten 19 Nitten 20 Tjue British Britisk Brother en Bror Brown BrunsegrtNo ratings yet

- Research in Camphill 2013Document5 pagesResearch in Camphill 2013segrtNo ratings yet

- LS Academic Calendar SY2018-2019Document5 pagesLS Academic Calendar SY2018-2019Yana RomeroNo ratings yet

- The State of Research On Situational Judgment Tests A Content Analysis and - 2014Document29 pagesThe State of Research On Situational Judgment Tests A Content Analysis and - 2014Flor Angela Leon GrisalesNo ratings yet

- Final Defense PDFDocument64 pagesFinal Defense PDFEricka RepomantaNo ratings yet

- Unit VI Social Problems of Interaction 1aDocument40 pagesUnit VI Social Problems of Interaction 1asaahasitha 14100% (1)

- Module 1-Brainstorming For Research TopicsDocument18 pagesModule 1-Brainstorming For Research TopicsPaul Drake PelagioNo ratings yet

- Research Assessment in The Humanities: Michael Ochsner Sven E. Hug Hans-Dieter Daniel EditorsDocument249 pagesResearch Assessment in The Humanities: Michael Ochsner Sven E. Hug Hans-Dieter Daniel Editorsguruh haris raputraNo ratings yet

- Curriculum Vitae Re: Okagu, Ogadimma. D (BSC, M.SC Nig) Email: Ogadimma - Okagu@Unn - Edu.Ng. Cell: +234 (0) 80-6704-7572Document4 pagesCurriculum Vitae Re: Okagu, Ogadimma. D (BSC, M.SC Nig) Email: Ogadimma - Okagu@Unn - Edu.Ng. Cell: +234 (0) 80-6704-7572Nwokemodo IfechukwuNo ratings yet

- Lesson Three Program EvaluationDocument5 pagesLesson Three Program EvaluationZellagui FerielNo ratings yet

- Preface: of Public Sector and Private Sector Banks"Document47 pagesPreface: of Public Sector and Private Sector Banks"madhuri100% (1)

- Practical Research 1: Informatic Computer Institute of Agusan Del Sur, IncDocument8 pagesPractical Research 1: Informatic Computer Institute of Agusan Del Sur, IncKathleen Joy PermangilNo ratings yet

- Ececmn FinlandDocument29 pagesEcecmn FinlandMiftah HazmiNo ratings yet

- Project-Work Guide: MECP-101 Master of Arts (Economics)Document32 pagesProject-Work Guide: MECP-101 Master of Arts (Economics)BestRater fearlesseverNo ratings yet

- MooseDocument1 pageMooseJoaquim Alves da SilvaNo ratings yet

- Evaluation of ResultsDocument2 pagesEvaluation of ResultsMary Joyce Catuiran SolitaNo ratings yet

- 2hassessment2Document9 pages2hassessment2api-435793479No ratings yet

- Literature Review On Digital ThermometerDocument4 pagesLiterature Review On Digital Thermometerafdtovmhb100% (1)

- A Study and Analysis of Bank LoansDocument83 pagesA Study and Analysis of Bank LoansEduardo Jones100% (1)

- Clean As You Go Policy in Honing The Scholasticans' Value of StewardshipDocument9 pagesClean As You Go Policy in Honing The Scholasticans' Value of StewardshipEra Luz Maria PrietoNo ratings yet

- Topic of Propossal MethodDocument3 pagesTopic of Propossal MethodY DươngNo ratings yet

- What - Research QuestionDocument16 pagesWhat - Research QuestionDevesh UniyalNo ratings yet

- Parents Rearing A ChildDocument30 pagesParents Rearing A ChildIsabel BantayanNo ratings yet

- UNICEF Philippines ECCD and BE Report OPM Final 30mar2017Document128 pagesUNICEF Philippines ECCD and BE Report OPM Final 30mar2017berrygNo ratings yet

- Cse N13 February2019 PDFDocument152 pagesCse N13 February2019 PDFDaniel MargineanNo ratings yet

- Curriculum Vitae OutlineDocument2 pagesCurriculum Vitae OutlineManu Krishnan MagvitronNo ratings yet

- Reflexivity in Social Research (2021)Document91 pagesReflexivity in Social Research (2021)방운No ratings yet

- 2 Work CorrectionDocument19 pages2 Work CorrectionIrene MoshaNo ratings yet

- Ping Project Instructions Rubric 2015Document14 pagesPing Project Instructions Rubric 2015api-296773017100% (1)

- 1 s2.0 S2095496423000985 MainDocument10 pages1 s2.0 S2095496423000985 Mainjmanuel.beniteztNo ratings yet