Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Scopes Trial

Uploaded by

Ilkin JamalOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The Scopes Trial

Uploaded by

Ilkin JamalCopyright:

Available Formats

The Scopes Trial

The Scopes Trial remains the best-known encounter between science and

religion to take place in the United States. It occurred in 1925, soon after the

Tennessee state legislature passed a statute forbidding public-school

teachers from instructing students in the theory of human evolution. The law

was the rst major success of an intense national campaign by protestant

fundamentalists against the teaching of organic evolution in public schools.

The so-called antievolution crusade, which had begun in earnest three years

earlier, aroused erce opposition from many American scientists, educators,

and civil libertarians.

After passage of the Tennessee antievolution statute, the growing public

controversy soon focused on the small Tennessee town of Dayton, where a

local science teacher named John T. Scopes ( 1900 - 1970 ) accepted the

invitation of the American civil Liberties Union ( ACLU) to challenge the new

law in court. The media promptly proclaimed it the trial of the century as this

young teacher stood against the forces of fundamentalist religious law-

making.

SETTING THE STAGE.

The trial itself was more a media circus than a serious criminal prosecution.

Such a trial would put Dayton on the map. Such a trial would put Dayton on

the map, Rappleyea explained to other civic leaders. They agreed and asked

John Scopes to stand trial.

Scopes disapproved of the new law and accepted an evolutionary view of

human origins. John also inclined toward his fathers view about government

and religion but in an easygoing way. When asked by the local board

president and the school superintendent if he would stand trial for teaching

evolution, Scopes readily consented, even though he doubted that he had

ever violated the law.

BRYAN versus Darrow

Ever since Charles Darwin had published his theory of evolution in 1859,

some conservative Christians had objected to the materialistic implications of

its naturalistic explanation for the origins of man. Many of the maintained that

God especially created the rst humans , as the bible suggested in Genesis,

and rejected the notion that people had evolved from brutes.

Early in the twentieth century, these objections intensied with the spread of

fundamentalism as a reaction by some traditional American PrProtestants to

increased religion liberalism within their mainline denominations , especially

because many came to see Darwinian theories of survival of the ttest behind

excessive militarism, imperialism, and laissez-faire capitalism - the three

greatest sins in Bryans political theology.

Bryan called for the enactment of state restrictions on teaching the Darwinian

theory of human in public schools. Bryans pending appearance in Dayton

drew in Clarence Darrow. By the twenties, Darrow stood out as the most

famous trail lawyer in America. He had gained fame as the countrys premier

defender of labor organizers and political radicals but also was known for his

militant opposition to religious inuences in public life, particularly to biblically

inspired legal restrictions on personal freedom. In this cause, he was a

pioneer. His opposition to religious lawmaking stemmed from his belief that

revealed religion, especially Christianity, divided people into warring sects,

caused them to be judgmental. Darrow sought to expose biblical literalism as

both irrational and dangerous. He welcomed the hullabaloo surrounding the

antievolution crusade. It rekindled interest in his attacks on the Bible, which

one had appeared hopelessly out of date in light of modern developments i

Mainline Christian thought but now seemed to regain relevance with the rise

of fundamentalism.

With Bryan and Darrow on board, Dayton civic leaders could only marvel at

the success of their publicity scheme. They feted both men with banquets in

their honor and housed them in two of Daytons nest private homes.

NATIONAL INTEREST.

The prospect of these two renowned orators - Bryan and Darrow - actually

litigating the profound issues of science versus religion and academic

freedom versus popular control over public education turned the trial into a

media sensation at the time and into the stuff of legend thereafter.

Two hundred reporters covered the story in Dayton, including some of the

countrys best correspondents, who represented many of the major

newspapers and magazines.

Newsreel cameras recorded the encounter, with the lm own directly to

major Northern cities for projection in movie houses. The media billed it as

the trial of the century before it ever began, and it lived up to its billing.

Darrow, for his part, concentrated on debunking fundamentalist reliance on

revealed Scripture as a source of knowledge about nature that was suitable

for setting educational standards. Their common goal, as Hays stated at the

time, was to make it possible that laws of this kind will hereafter meet the

opposition of an aroused public opinion.

The prosecution countered with a half-dozen local attorneys led by the states

able prosecutor and future U.S. senator, Tom Stewart, plus Bryan and his

son, William Jennings Jr., a California lawyer. In court, they focused on

providing that Scopes broke the law and objected to any attempt to litigate

the merits of that statute.

The elder Bryan, who had not practiced law for three decades, stayed

uncharacteristically quiet in court and saved his oratory for lecturing the

assembled press and public outside the courtroom about the vices of

teaching evolution and the virtues of majority rule.

As the actual trial played itself out,however, Darrow managed to frustrate

Bryans plan by waiving his own close because, under Tennessee practice,

the defense controlled whether there would be closing arguments.

The Trial UNFOLDS.

First came jury selection. Darrow typically stressed this part of a trial as being

critical for the defense and often spent weeks going through hundreds of

veniremen before settling on twelve jurors who just might be open to his

arguments and acquit his typically notorious defendant. Darrow had a

different objective at the Scopes trial, however. He wanted to convict the

statute rather than acquit the defendant, and only judges could do this. Jurors

simply applied the law to the facts of the case. Darrow could have won an

acquittal by arguing that Scopes never violated the statute, but that would

have left the statute intact. Instead, the defense sought either to have the trial

judge strike the statute, which was all but beyond his role , or to have Scopes

convicted and then appeal to a higher court, which could review the statute.

Hence Darrow quickly accepted even the simplest of jurors, including several

who had never heard of the theory of evolution and one who could not read.

No sooner was the jury selected than it was excused from the courtroom --

for days -- as the parties wrangled over defense motions to strike the statute

as unconstitutional. Although these arguments occasionally soared into

dramatic pleas from the defense for academic freedom and from the

prosecution for majority rule, they generally skirted the underlying issues of

science versus religion.

The prosecution then presented uncontested testimony by students and

school ofcials that Scopes had taught evolution. After the prosecutions brief

presentation, the defense offered the testimony of fteen national experts in

science and religion, all prepared to defend the theory of evolution as a valid

scientic theory that could be taught without public harm.

BRYANS testimony.

Frustrated by his failure to discredit the antievolution law through the

testimony of scientists and liberal theologians, Darrow sought the same result

by inviting Bryan to take the witness stand and face questions about it.

Although he could have declined, Bryan accepted Darrows challenge. But

Stewart could not control is impetuous eco-counsel, especially because the

judge seemed eager to hear Bryan defend the faith.

Best of all for Darrow, no good answers to the questions existed.

Darrow questioned Bryan as a hostile witnessYou claim that everything in the

Bible should be literally interpreted ?

I peppering him with queries and giving him little chance to explain.

On the stump, Bryan effectively championed the cause of biblical faith by

addressing the great questions of life: The special creation of human in Gods

image gave purpose to every person, and bodily resurrection of Christ gave

hope for eternal life to believers. But Darrow did not inquire about these

grand miracles. For many Americans, laudable simple faith became simple

faith became laughable crude belief when applied to Jonahs whale, Noahs

ood, and Adams rib. Yet Bryan acknowledged accepting each of these

biblical miracles on faith and professed that all miracles were equally easy to

believe.

In an apparent concession to modern astronomy , Bryan suggested that God

extended the day for Joshua by stopping the earth rather the sun. Bryan

afrmed his understanding that the Genesis days of creation represented

periods of time.

Legacy

Despite Bryans stumbling on the witness stand both sides effectively

communicated their message from Dayton - maybe not enough to win

converts but at least sufciently to energize those already predisposed

toward their viewpoint.

Underlying this rift, surveys of public opinion consistently reveal that

Americans remain nearly evenly split between opinion accepting the scientic

theory of human evolution and those believing that God specially created

Adam and Eve within the past ten thousand years.

With time and countless retellings, the Scopes trial has become part of the

fabric of American culture. For some, it grew to symbolize the treat to

scientic freedom and progress posed not simply by antievolution but also by

religiously motivated lawmaking generally. For others it suggested a rowing

hostility to religious faith within the scientic community and modern

American society.

You might also like

- Case Reflection Scope TrialDocument4 pagesCase Reflection Scope TrialMikey CupinNo ratings yet

- The Scopes TrialDocument4 pagesThe Scopes Trialmelf toNo ratings yet

- The Other Side of the Scopes Monkey Trial: At Its Heart the Trial Was about RacismFrom EverandThe Other Side of the Scopes Monkey Trial: At Its Heart the Trial Was about RacismNo ratings yet

- The Scopes Monkey Trial Students WorksheetDocument4 pagesThe Scopes Monkey Trial Students Worksheetapi-237751184No ratings yet

- News and Comments: The Teaching of Creation and Evolution in The State of TennesseeDocument8 pagesNews and Comments: The Teaching of Creation and Evolution in The State of TennesseeMilan StepanovNo ratings yet

- Getting Over Equality: A Critical Diagnosis of Religious Freedom in AmericaFrom EverandGetting Over Equality: A Critical Diagnosis of Religious Freedom in AmericaNo ratings yet

- On Creationism ModernDocument14 pagesOn Creationism ModernEva Anne ZerovnikNo ratings yet

- Scopes Monkey Trial Research PaperDocument4 pagesScopes Monkey Trial Research Paperkgtyigvkg100% (1)

- Research Paper On The Scopes Monkey TrialDocument6 pagesResearch Paper On The Scopes Monkey Trialgz8xbnex100% (1)

- Saving Darwin: How to Be a Christian and Believe in EvolutionFrom EverandSaving Darwin: How to Be a Christian and Believe in EvolutionRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (21)

- Biology EssayDocument1 pageBiology EssayKeaton StarksNo ratings yet

- Scopes TrialDocument29 pagesScopes Trialapi-487270839No ratings yet

- Ann BibDocument5 pagesAnn BibSean F-WNo ratings yet

- Abortion at the Crossroads: Three Paths Forward in the Struggle to Protect the UnbornFrom EverandAbortion at the Crossroads: Three Paths Forward in the Struggle to Protect the UnbornNo ratings yet

- The Center Holds: The Power Struggle Inside the Rehnquist CourtFrom EverandThe Center Holds: The Power Struggle Inside the Rehnquist CourtRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (2)

- The Scopes Monkey TrialDocument1 pageThe Scopes Monkey TrialBeboy TorregosaNo ratings yet

- The Ten Offenses: Reclaim the Blessings of Eternal TruthsFrom EverandThe Ten Offenses: Reclaim the Blessings of Eternal TruthsRating: 1 out of 5 stars1/5 (1)

- HIS-144-RS-Darwinism and American Society WorksheetDocument3 pagesHIS-144-RS-Darwinism and American Society Worksheetnnpw9rjgsvNo ratings yet

- Evolution, Creationism, and Other Modern Myths: A Critical InquiryFrom EverandEvolution, Creationism, and Other Modern Myths: A Critical InquiryRating: 2.5 out of 5 stars2.5/5 (10)

- Language of God: A Scientist Presents Evidence for BeliefFrom EverandLanguage of God: A Scientist Presents Evidence for BeliefRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (52)

- 2006.07 The Scoop On ScopesDocument2 pages2006.07 The Scoop On ScopesWilliam T. PelletierNo ratings yet

- Galileo Goes to Jail and Other Myths about Science and ReligionFrom EverandGalileo Goes to Jail and Other Myths about Science and ReligionRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (15)

- Preachers, Pedagogues, and Politicians: The Evolution Controversy in North Carolina, 1920-1927From EverandPreachers, Pedagogues, and Politicians: The Evolution Controversy in North Carolina, 1920-1927No ratings yet

- The Making of Massive Resistance: Virginia's Politics of Public School Desegregation, 1954-1956From EverandThe Making of Massive Resistance: Virginia's Politics of Public School Desegregation, 1954-1956No ratings yet

- Monkey Girl: Evolution, Education, Religion, and the Battle for America's SoulFrom EverandMonkey Girl: Evolution, Education, Religion, and the Battle for America's SoulRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (61)

- A Community Built on Words: The Constitution in History and PoliticsFrom EverandA Community Built on Words: The Constitution in History and PoliticsRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (2)

- God Vs ScienceDocument10 pagesGod Vs SciencevjmartinNo ratings yet

- Deception by Design: The Intelligent Design Movement in AmericaFrom EverandDeception by Design: The Intelligent Design Movement in AmericaNo ratings yet

- Creation and the Courts (With Never Before Published Testimony from the "Scopes II" Trial): Eighty Years of Conflict in the Classroom and the CourtroomFrom EverandCreation and the Courts (With Never Before Published Testimony from the "Scopes II" Trial): Eighty Years of Conflict in the Classroom and the CourtroomRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (4)

- God vs. Science: Dan Cray/Los AngelesDocument36 pagesGod vs. Science: Dan Cray/Los AngelesFides De Guzman YbanezNo ratings yet

- American Christian FundamentalismDocument7 pagesAmerican Christian FundamentalismjoyceNo ratings yet

- Reconsidering Roosevelt on Race: How the Presidency Paved the Road to BrownFrom EverandReconsidering Roosevelt on Race: How the Presidency Paved the Road to BrownNo ratings yet

- Our Christian Founding Fathers: “. . . This Is a Christian Nation.”From EverandOur Christian Founding Fathers: “. . . This Is a Christian Nation.”No ratings yet

- Ronald L. Numbers (2007) Science and Christianity in Pulpit and PewDocument207 pagesRonald L. Numbers (2007) Science and Christianity in Pulpit and PewGustavo LagaresNo ratings yet

- Pagans and Christians in the City: Culture Wars from the Tiber to the PotomacFrom EverandPagans and Christians in the City: Culture Wars from the Tiber to the PotomacNo ratings yet

- Inherit The WindDocument5 pagesInherit The WindzcxzkjzkCJhNo ratings yet

- Annotated Bibliography Primary Sources: You Missed in History Class, How Stuff Works, 24 May 2017Document21 pagesAnnotated Bibliography Primary Sources: You Missed in History Class, How Stuff Works, 24 May 2017Maya SrinivasanNo ratings yet

- Annotated BibliographyDocument21 pagesAnnotated BibliographyMaya SrinivasanNo ratings yet

- American Philosophical SocietyDocument11 pagesAmerican Philosophical SocietyRoss DanielsNo ratings yet

- Clarence Darrow 10 FactsDocument4 pagesClarence Darrow 10 FactsJoesterNo ratings yet

- The Guardians: Kingman Brewster, His Circle, and the Rise of the Liberal EstablishmentFrom EverandThe Guardians: Kingman Brewster, His Circle, and the Rise of the Liberal EstablishmentNo ratings yet

- Abortion, The Supreme Court, American WishesDocument5 pagesAbortion, The Supreme Court, American WishesBugsy PimbertonNo ratings yet

- Nine Black Robes: Inside the Supreme Court's Drive to the Right and Its Historic ConsequencesFrom EverandNine Black Robes: Inside the Supreme Court's Drive to the Right and Its Historic ConsequencesNo ratings yet

- The Supreme Court in the Intimate Lives of Americans: Birth, Sex, Marriage, Childrearing, and DeathFrom EverandThe Supreme Court in the Intimate Lives of Americans: Birth, Sex, Marriage, Childrearing, and DeathNo ratings yet

- A Most Uncertain Crusade: The United States, the United Nations, and Human Rights, 1941–1953From EverandA Most Uncertain Crusade: The United States, the United Nations, and Human Rights, 1941–1953No ratings yet

- Proclaim Liberty Throughout All the Land: How Christianity Has Advanced Freedom and Equality for All AmericansFrom EverandProclaim Liberty Throughout All the Land: How Christianity Has Advanced Freedom and Equality for All AmericansNo ratings yet

- The Bill of Rights in Modern America: Third Edition, Revised and ExpandedFrom EverandThe Bill of Rights in Modern America: Third Edition, Revised and ExpandedNo ratings yet

- Deep Commitments: The Past, Present, and Future of Religious LibertyFrom EverandDeep Commitments: The Past, Present, and Future of Religious LibertyNo ratings yet

- Bitterness & HatredDocument3 pagesBitterness & HatredcccvogNo ratings yet

- The Marian DogmasDocument12 pagesThe Marian DogmasJoe PepNo ratings yet

- Introduction - To - Srimad - Bhagavad-Gita PDFDocument22 pagesIntroduction - To - Srimad - Bhagavad-Gita PDFMaitraya100% (1)

- What Is IfaDocument15 pagesWhat Is IfaHazel100% (8)

- Full Assurance by Harry A. Ironside - 01Document4 pagesFull Assurance by Harry A. Ironside - 01300rNo ratings yet

- Baptism of JesusDocument38 pagesBaptism of JesusKookie caleNo ratings yet

- Theosis of The Early Church FathersDocument17 pagesTheosis of The Early Church FathersAnonymous D83RFJj34No ratings yet

- Aditya Hridayam WikiDocument5 pagesAditya Hridayam WikimsarandossNo ratings yet

- 25890839Document5 pages25890839hafizjanNo ratings yet

- Deuteronomy 328 and The Sons of GodDocument27 pagesDeuteronomy 328 and The Sons of Godabbraxas100% (1)

- 6 Apr 07Document5 pages6 Apr 07Joseph WinstonNo ratings yet

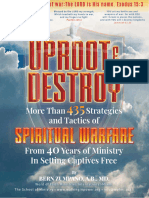

- Uproot and DestroyDocument1,083 pagesUproot and DestroyIzea DelanoNo ratings yet

- AtheismDocument3 pagesAtheismKarel Michael DiamanteNo ratings yet

- Reply To Professor Michael McClymondDocument9 pagesReply To Professor Michael McClymondakimel100% (6)

- Welcome To Trinity Lutheran Church: Sunday, May 17, 2020 Sixth Sunday of EasterDocument5 pagesWelcome To Trinity Lutheran Church: Sunday, May 17, 2020 Sixth Sunday of EasterEileen WoyenNo ratings yet

- Linqvoolkesunasliq SerbestDocument7 pagesLinqvoolkesunasliq SerbestAzizaNo ratings yet

- I See Satan FallingDocument114 pagesI See Satan FallingŽeljko Porobija93% (14)

- P01171 Ex PDFDocument20 pagesP01171 Ex PDFLasarlj LjNo ratings yet

- 22 Bible Verses About Healing Through DisciplesDocument5 pages22 Bible Verses About Healing Through DisciplesGlenn VillegasNo ratings yet

- Samuel Pipim-Inventing New Styles of WorshipDocument9 pagesSamuel Pipim-Inventing New Styles of WorshipSamuel PipimNo ratings yet

- Marriage God's WayDocument14 pagesMarriage God's Waykingdomfaith80% (5)

- Meconi, S. J. - Sacred Scripture and Secular Struggles PDFDocument299 pagesMeconi, S. J. - Sacred Scripture and Secular Struggles PDFvetustamemoriaNo ratings yet

- Principles and Guidelines For Interfaith DialogueDocument7 pagesPrinciples and Guidelines For Interfaith Dialoguerichbert100% (1)

- Sheikh Toosi Book Al GhaybaDocument284 pagesSheikh Toosi Book Al GhaybaKryptic_Knowhow67% (3)

- Eastern PhilosophiesDocument6 pagesEastern PhilosophiesLyza Sotto ZorillaNo ratings yet

- Richard Rohr 6Document75 pagesRichard Rohr 6fnavarro2013No ratings yet

- 40 Hadith of Nawawi+additions of Ibn Rajab - EngDocument17 pages40 Hadith of Nawawi+additions of Ibn Rajab - EngAbul HasanNo ratings yet

- Seyyed Hossein Nasr - An Introduction The Islamic Cosmological DoctrinesDocument346 pagesSeyyed Hossein Nasr - An Introduction The Islamic Cosmological DoctrinesMoreno Nourizadeh100% (4)

- Pastor. The History of The Popes, From The Close of The Middle Ages. 1891. Vol. 39Document520 pagesPastor. The History of The Popes, From The Close of The Middle Ages. 1891. Vol. 39Patrologia Latina, Graeca et OrientalisNo ratings yet

- Cantors CompanionDocument111 pagesCantors CompanionPaul Elliott100% (1)