Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Questioning Cage's Influence on Music

Uploaded by

malcolm_atkins1Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Questioning Cage's Influence on Music

Uploaded by

malcolm_atkins1Copyright:

Available Formats

Malcolm Atkins

Cage is dead

page 1 of 12

Cage is dead (and Schoenberg is dead although Boulez is still alive).

The problems with the canonisation of the work of an experimentalist.

Abstract

The paper questions why we have made Cage such an authoritative figure about sound and music when

his definition of music does not correspond in any way to any accepted definition. I use his statement that

in terms of constructing music a structure based on durationsis correctwhereas harmonic structure is

incorrect as a basis for debate.

I first contextualise Cages ideas by suggesting their source in

Contemporary ideas of the post war avant-garde

His interest in Eastern philosophy - music is to sober and quiet the mind

His engagement with other art forms

I argue that all he espoused was of his time but his conflation of different ideas was unique to any

musician of his time.

I question his statement that music is only meaningful in the contrast of sound and silence as follows:

This just doesnt equate to what we mean by silence

Cage over privileges silence to ignore other aspects of the sonic environment (such as timbre)

Is Cage an apologist for an unjust capitalist world ?

Even people Cage admired in using silence (such as Morton Feldman) use it as part of an

unfolding sonic construction

Cage did not really embrace all sounds in the way he often advocated for others. He was selective

on what he would allow.

I conclude by emphasising the importance of Cage and the questions he raised but suggest that if we

uncritically accept his ideas we devalue his artistic and philosophical contribution.

Whenever anyone asked him about Zen, the great master Gutei would quietly raise one finger into the

air. A boy in the village began to imitate this behavior. Whenever he heard people talking about

Gutei's teachings, he would interrupt the discussion and raise his finger. Gutei heard about the boy's

mischief. When he saw him in the street, he seized him and cut off his finger. The boy cried and began

to run off, but Gutei called out to him. When the boy turned to look, Gutei raised his finger into the air.

At that moment the boy became enlightened. (Suler, 1997)

People ask what the avant-garde is and whether it is finished. It isnt. There will always be one. The

avant-garde is flexibility of mind. And it follows like day, the night from not falling prey to government

Malcolm Atkins

Cage is dead

page 2 of 12

and education. Without the avant-garde nothing would get invented. If your head is in the clouds keep

your feet on the ground. If your feet are in the ground keep your head in the clouds. (Montague,1985,

p.210)

Introduction

I will talk about Cage because he is more than any other composer associated with the notion of silence

albeit his own continually revised definition of this term and because the legacy of his work has

contributed to the argument that erupted in 2012 in the centenary of his birth when 250 composers,

performers, administrators and supporters of contemporary music, headed by Sir

Harrison Birtwistle and Sir Peter Maxwell Davies criticised Sound and Music the

newly consolidated funding body for contemporary music for failing to support

traditional composition and giving a bland and unfocused endorsement of sound art (The

Holst Foundation).

I will start from a statement of John Cage apparently made in 1961 and assess its relevance to the

structuring of sound in our time. This was quoted by Pauline Oliveros as the basis for her piece From

Unknown Silences (1996). I cant find the source in the work credited although there are a number of

similar statements by Cage dotted through his works so I believe it is accurate even if it may be a

paraphrase of Cage :

Sound has four characteristics: pitch, timbre, loudness, and duration.

The opposite and necessary coexistent of sound is silence. Therefore, a

structure based on durations (rhythmic: phrase and time lengths) is

correct (corresponds with the nature of the material), whereas harmonic

structure is incorrect (derived from pitch, which has no being in

silence). Cage 1961 quoted in Oliveros 1

This is a radical reappraisal of the function of sound in relation to its structuring in music, it is about the

physics of sound as opposed to a more traditional Western view of music as an agreed method of

communication where harmony, melody and rhythm comprise communicative conventions within a genre.

I will argue that like much of Cages work this is an invaluable prompt to reconsider how we think of

music but that it is inherently problematic because it just doesnt correspond to what people mean by

music. It is a personal opinion which is supported by no real evidence or logical argument. It works as part

of a poetical vision of the role of music which supports a personal philosophy that combines Eastern

philosophy with liberal economics.

1

A longer quote from Fetterman (1996,p. 19) gives more context:

Silence to my mind is as much a part of music as sound. Now, starting with the concept, we go to the accepted qualities of

music pitch, timbre, volume and duration. Which of these partakes of both silence and sound ? Only duration. But silence and

sound have duration.

Therefore I take my sounds when I have decided what they are going to be and place them in this background of silence. This

reduces the structure of the composition to pure rhythm, nothing else.

Also, I make no attempt to say anything. Beethoven, wrote from a subjective emotion which he objectified in his work.

It,and the sounds I use, exist solely for their own sake unrelated to anything else (Silence, Sound in Composition Are Stressed

1951)

There is also a similar quote in Silence in the Lecture on Satie (Cage, 2004, p. 80: . 'If you consider that sound is characterized

by its pitch, its loudness, its timbre, and its duration, and that silence that is the opposite and, therefore, the necessary partner of

sound, is characterized only by its duration, you will be drawn to the conclusion that, of the four characteristics of the material

of music, duration, that is, time length, is the most fundamental. Silence cannot be heard in terms of pitch or harmony: it is

heard in terms of time length'

Malcolm Atkins

Cage is dead

page 3 of 12

For this reason the uncritical canonisation of Cages work and statements can be problematic. A statement

made by a unique outsider at a particular time in response to particular concerns of that time which was

designed to question established beliefs is not a valid recourse to replace those beliefs. Because Cages

work and philosophy were so linked it is dangerous to canonise his work and replicate it through

institutionally funded cover bands because his work carries philosophical ideas which need to be

questioned. Where cover bands replicate popular music of the 50s and 60s this is (fortunately) not

accompanied with inane philosophical pronouncements of Mick Jagger or Paul McCartney or Pete

Townshend. When people cover Cardew his Maoist rantings are politely forgotten. Cages ideas are more

enigmatic and often charmingly expressed and they have to be engaged with by anyone who performs his

music. But they do deserve serious questioning because they are explicit in all he does.

This situation is itself exacerbated by the commodification of learning where different institutions support

different brand names and approaches. Musical institutions have always been liable to fanatical

codification of practice as the relentless application of total serialism in musical institutions of the 1960s

demonstrated. This is partly due to the hierarchical nature of music making in the West which Cage did

challenge. But it is also due to the collaborative nature of music making which leads to groups of

musicians adopting mutually beneficial approaches which create their particular bases of power

something that happens far less in the visual arts where collaboration is more problematic. Ironically,

Cage and the experimentalists who followed him were generally barred from musical institutions until

their eventual canonisation when their work would be grant funded for performance 2.

Why did Cage develop his particular ideas on sound and silence ?

I would identify three key areas of influence on Cage: contemporary concerns of the avant-garde; his

personal philosophy; his particular interest in other art forms (most notably visual art and dance). I am

taking the avant-garde as including Cage in his early career but following Nyman in seeing him as part of

an experimental music movement from the 1950s.

01 Cage and trends within the avant-garde

The modernist challenge to the legacy of Romanticism in music had led to the following techniques. All

present in Cage:

I will summarise these by list but talk about them in more depth if anyone is interested.

Challenging diatonic organisation

Challenging teleological development

Use of any noise.

Use of parallel sound worlds

Use of extended techniques and modification of instruments

Challenging repetition or undermining it by excess

Use of processes to structure sound including chance techniques

Challenging personal expression and the emotive power of music

Challenging diatonic organisation

2

Nyman,1999 (p. XV in 1972.. experimental music; was a minority sport, played in generally non-musical spaces in front of

disciples drawn more likely from fine art, dance o film worlds than from music; was despised, ignored or cavalierly used as raw

material by the then-dominant avant-garde, and the cultural institutions who supported it

Malcolm Atkins

Cage is dead

page 4 of 12

Schoenberg and the Second Viennese School had effectively turned out the lights as Webern declared

when they created music without tonal centre. Schoenberg created serialism to replace diatonic

organisation of sound and later taught Cage whose early works were influenced by Schoenberg.

The idea of using a defined process to create a work rather than intuitively working within boundaries

was a post-war extension of Schoenbergs ideas as he saw himself as an artist who composed intuitively

even within the strictures of serialism. Total serialism was the depersonalised result of this. Feldman

summaries the result of this as follows: What music rhapsodizes in todays cool language, is its own

construction. The fact that Boulez and Cage represent opposite extremes of modern methodology is not

what is interesting. What is interesting is their similarity. In the music of both men, things are exactly what

they are no more, no less. In the music of both men, what is heard is indistinguishable from its process

The duality of precise means creating indeterminate emotions is now associated only with the past (quoted

in Nyman,1999, p. 2)

Challenging teleological development

Satie (who Cage frequently promoted) had challenged the idea of music building to an inevitable climax

and of unfolding a narrative. He created small pieces that go nowhere (deliberately). Webern also created

miniatures The Bagatelles for string quartet many of which are less than a minute long.

Use of any noise.

The use of a wider palette of sounds which included noise was initiated by the futurists . There had been

some experimentation around this by Mahler who incorporated a range of sounds in his symphonies as

well as Ives

Satie had used real world sounds (a revolver for instance in Relache)

Use of parallel sound worlds

Ives had explored running different musics in parallel in the same piece.

Use of extended techniques and modification of instruments

Cowell (who taught Cage) had experimented with using the inside of the piano. Russolo had explored

creating new instruments

Challenging repetition or undermining it by excess

Webern and Schoenberg had explored stating ideas with no repetition hence the brevity of some of

Weberns atonal pre-serial works. Satie created works such as Vexations which were designed for endless

repetition.

Use of process to structure sound including chance techniques

As often pointed out there are examples of use of chance music in Mozarts dice piece. Contemporaries of

Cage also used chance which was a natural choice for those seeking to avoid egotistical expression.

Challenging personal expression and the emotive power of music

Webern created beautiful detached and self-contained sound worlds carefully constructed and using

traditional canonic processes with serialism in works such as Symphony.

Malcolm Atkins

Cage is dead

page 5 of 12

The post-war avant-garde took Weberns ideas further surely as part of a rejection of all that had led to

the second world war. They were creating a new scientifically beautified world which eschewed Romantic

lyricism and Romantic egotism - although ironically one of the most popular works from the 1940s is a

series of songs by a German who had worked under the Nazis Strauss Four Last Songs of 1948

perhaps indicating the way Romanticism could not be eradicated by the new composers

Cage quoted Satie (2004, p.82) on simplicity in expression as follows:

It (LEsprit Nouveau) teaches us to tend towards an absence (simplicite) of emotion and an inactivity

(fermete) in the way of prescribing sonorities and rhythms which lets them affirm themselves clearly, in a

straight line from their plan and pitch, conceived in a spirit of humility and renunciation.

02 Cage, mysticism and eastern philosophy

In general the avant-garde (Schoenberg, Berg, Webern before the second world war Boulez and

Stockhausen as Cages contemporaries) have tended to continue the role of the composer as Romantic

artist. The composer was still communicating a personal vision to an audience even if that was mediated

through the use of process in some way. . Cage became aware of and staunchly opposed to this in his

work.

For Cage this was part of a philosophical shift from using the organisation of sound to communicate to

one of using music to sober and quiet the mind thus rendering it susceptible to divine influences.

Please play Extract 01 purpose of music (extract from Cott,1963)

Whether this philosophical shift in his approach to music was responsible for his interest in silence or

vice-versa the move from intention determined Cages compositional approach from 1951 and the works

such as the silence piece of 1952 which he is most famous for 3.

In fact his definition of silence went through a series of stages which culminated in this term bearing little

relation to its meaning in general parlance, ultimately equating silence to sounds which lacked

intentionality. As with Cages use of the term music there seems to be a consistent revision of terms to

meet an ulterior spiritual purpose. Rather than just saying, as Wittgenstein would have, that language is

not sufficient for our needs, or that language is about agreed uses for terms he attempts to promote a

spiritual agenda through an alternative use of terms.

03 Cage and other art forms

Cage was continually engaged with other art forms alongside music. Much of his music was created in

collaboration with dance but he was also influenced by approaches in visual art which enabled him and his

circle to adopt new approaches to traditional compositional role of pulling strings at a distance, he was

also aware of the importance if theatrical presentation.

His ideas that music was not to express meaning or intention is also an extension of ideas expressed in

the 19th century in the dispute between followers of Brahms (who felt that music could not express

anything other than its own meaning i.e. no meaning that could be translated into words) and followers

of Wagner who saw music as supporting and enhancing linguistic or narrative meaning (as in Strausss

interminable tone poems).

Malcolm Atkins

Cage is dead

page 6 of 12

For his circle the interest in visual art (and Feldman testifies to this in all his essays and comments

quoted Nyman,1999, p. 51) led to different approaches to organising sound through imitation of mobiles;

graphic scores; documenting of equipment rather than traditional notation etc

His creation of the silent piece could be seen as following the example of Rauschenberg. In his article on

Rauschenberg (2004, p.98) he says: To Whom it May Concern: The white paintings came first; my silent

piece came later.

Satie declared it was painters who taught me the most about music (Volta,1994, p. 8)

All the components of Cages aesthetic attitude and all the compositional techniques he used were rooted

in his time and traditions around him including the American adoption of oriental philosophy as well as

traditions of mysticism expressed by Thoreau.

What was unique about Cage was simply the configuration of them in one individual and the radical

philosophy that he discovered from these diverse influences. Clearly his projection of personality in

supporting his work was important. He was always available to discuss his work and ironically became

one of the only composers of his time who could survive through the sales of his work.

Also, as documented in Ross The Rest is Noise cold war politics in America in the 1950s led to a serious

propagation of new music and art. The freer and more iconoclastic the more it contrasted with the

constraints of Soviet realism. Cage was operating at a fortunate time for the avant-garde.

Is this statement valid in any way ?

Because Cage has had so much of an influence on all the arts and because he is such an engaging and

charismatic anti-establishment figure we tend to sympathise with him in the attacks that have been made

on him. Perhaps in this he fulfils the Hollywood promoted archetype of the individual triumphing against

the establishment.

I will attempt to focus on his arguments about sound and the problems with it.

Criticism 01

The main criticism of this statement (and of Cages approach to music) must be that it is essentially

meaningless as an approach to composition as generally understood. In general understanding music

communicates from musician to audience through agreed conventions of the organisation of sound which

can include silence but tends to privilege the units of communication whether pitch or timbre or

dynamics or silence between sounds

In a sense it redefines what music is and if the definition of a word is in accepted use then Cage is not

referring to music when he says its purpose it to quiet the mind rather than to express an artistic vision or

to give any implicit or explicit message. The following explains his position further:

Malcolm Atkins

Cage is dead

Please play Extract 02 the basic musical experience is the absence of music

Cott,1963)

page 7 of 12

(extract from

But is Cage talking about music or a new discipline ? If his musical world is for a purpose that was not

shared by more than a few other composers and listeners was it just a form of sound art ? It could still be

more artistically valid than traditional composition of his time but is it possible to talk about music outside

of communication and does Cages work communicate effectively anyway because his spiritual agenda is

implicit in what he does (and was frequently proclaimed to his audience) ?

A more conventional approach to music is that genres of music use agreed methods and conventions of

communication and these tend to involve pitch and harmonic rhythm. Silence is important in phrasing

pitch and harmonic development. But to define sound and hence musical construction in terms of silence

is as meaningless as saying that movement is defined by stillness and that as a result choreography should

be structured entirely by the contrast of stasis and motion; or that image is entirely dependant in the

contrast of light and dark and that therefore construction of a painting should be based entirely on this.

Clearly stasis, darkness and silence are important in all these arts but the method of communication of the

arts is based on agreed conventions which incorporate this.

The following statement by MacGilchrist in The Master and his Emissary reflects the way Cages ideas

have been incorporated into contemporary thought but the definition still retains what is seen as traditional

in music and emphasises a specific role for silence in music rather than the significant role that Cage

espouses:

Music consists entirely of relations, betweenness. The notes mean nothing in themselves: the tensions

between the notes, and between notes and the silence with which they live in reciprocal indebtedness, are

everything. Melody, harmony and rhythm each lie in the gaps, and yet betweenness is only what it is

because of the notes themselves. Actually the music is not just in the gaps any more than it is just in the

notes: it is in the whole that the notes and the silence make together. (Macgilchrist, 2010 , p. 72)

Criticism 02

Another problem is that if the West has over-privileged pitch Cage could be over-privileging silence.

Some music Buddhist chant perhaps or Shakuhachi music does use timbre extensively to maintain

variety over stretches of sound. We could argue that purity of sound is a particularly Western art music

approach and that Cage has fallen for that in failing to recognise the significance of timbre

Dynamics have also been of importance in the past. Structural dynamics are key to the works of the First

Viennese School think of any Mozart symphony or piano concerto and of the invention o the pianoforte

which parallels this interest.

Some works Tenneys On Never Having Written a Note for Percussion use dynamics on continuous

sound this is also a technique in some minimalist works such as the way Glass adds in extra

instruments to vary the sound of a line where the notes are constant.

Would Cage have been more accurate if he had said that any of the components of sound can be used to

structure sound and that in different genres different aspects have come to be recognised as significant to

structuring and communicating between musician and audience ?

Cage could argue that all the music I have discussed above is still about communication and intention to

communicate. If so we still have to be convinced of the argument that music is not about communication.

Malcolm Atkins

Cage is dead

page 8 of 12

The problem here is that Cage was communicating. He was communicating a spiritual vision which may

have been delivered indirectly but was still delivered through performance or even recording. He was

employing an intentional lack of intention by the act of creating sound for dissemination. He was also

proselytising his beliefs to support that dissemination.

If a composer such as Prt or Messiaen attempts to draw a composer to spiritual reflection through their

intentional construction of a sound world is that ultimately different to what Cage is trying to achieve

through indirect means ?

Cage would distinguish what he creates from the work of Messiaen and Prt by saying they create

objects whereas he is demonstrating process. But isnt the performance as framed by applause in a

concert hall a discrete object ? Zappa once declared ( in relation to Cage) that what makes a work

of art is the act of putting a frame around it. It is objectified by the social convention of the artist

declaring it to be art by framing it as art. Whatever that object demonstrates it is still an object.

Cage would counter by saying that in his work he usually refers to what he was doing for his own

purpose. The music was to quiet his mind. Others could subscribe to this but his starting point was

himself. But if this is the case isnt he continuing the legacy of the Romantic artist in pursuing a solitary

path of expression even if the method he uses are radical ? Besides which he performed his music to a

paying public was this opportunism or did he believe he had something to share ?

Criticism 03

In the Lecture on Something Cage expands his concept of silence to compare the way sound is immanent

in silence (and vice versa) in the same way that life is immanent in death.

The acceptance of death is the source of all life. So that listening to this music (Feldmans) one takes as

a springboard the first sound that comes along; the first something springs into nothing and out of that

nothing arises the next something; etc. like an alternating current. Not one sound fears the silence that

extinguishes it. And no silence exists that is not pregnant with sound' (Cage,2004, 128 ff)

In Experimental Music(ibid. p. 12) he declares that the purpose of writing music is a purposeful

purposelessness of a purposeless play. This play, however is an affirmation of life not an attempt to bring

order out of chaos nor to suggest improvements in creation

This spiritual acceptance of silence and all sound as part of life (which is so excellent once one gets ones

mind and ones desires out of its way and lets it act of its own accord (ibid. ) is at the same time

accompanied by an acceptance of human misery. In Four Statements on the Dance (ibid. p 93) Cage

reports his discussion with another composer as follows:

..I enjoyed the music, but I didnt agree with that program note about there being too much pain in the

worldI think theres just the right amount.

On the one hand we could see Cage as a benign acceptor of human frailty in the tradition of an artist such

as Mozart but on the other we could see him as an apologist for the inequalities of the free market system

from which he as an able self-publicist was able to benefit.

Cardew in Stockhausen serves Imperialism criticises Cage for his refusal to see art in Marxist terms and

engage with social problems and class issues.

Malcolm Atkins

Cage is dead

page 9 of 12

Although Cardews Maoist phase is generally ignored for its embarrassing references to the disgraced

leader there is something odd in Cages attempt to link his music to the world but his refusal to deal with

the problems of the world although his position is consistent with a Zen view

Cardew discusses Cages reception in 1972 as follows: What happens nowadays is that

revolutionary students boycott Cages concerts at American universities, informing

those entering the concert hall of the complete irrelevance of the music to the

various liberation struggles raging in the world

Criticism 04

In the Lecture on Something Cage examples Feldmans use of silence in his work.

However, Feldmans work does tend to follow an intuitive path where his intention is apparent in the

structuring. His use of silence is part of the full tapestry of construction that involves all elements of

sound. Feldmans work seems to constitute discrete and self-contained objects within the aesthetic

traditions of Western art that Cage was rejecting ( as also do Weberns works which he admired so much

and even the works of Satie).

I cant think of anyone Cage admired who followed the same path as himself in music although we may

be able to find parallels in other art forms.

Criticism 05

A further criticism of Cages development of his notions of silence is of the limits he imposed to the

sounds that were admissable. Kahn in Silence and Silencing argues that while venturing to the sounds

outside music, his ideas did not adequately make the trip; the world he wanted for music was a select one,

where most of the social and ecological nose was muted and where other more proximal noises were

suppressed (1997 , p.556).

Khan argues(p. 558) that Cage ultimately declared silence to be all the sound we dont intend. There is no

such thing as absolute silence. Therefore silence may very well include sounds and more and more in he

twentieth century does, The sound of jet planes, of sirens etc

However Kahn goes on to point out the problems Cage had in being disinterested enough to open his

mind to all sound: his dislike of The German Romantic tradition and much in the whole Western art

tradition; his dislike of jazz for ego-driven improvisation, measured time, orature an collectivism; his

dislike of commercial music and muzak. He was not showing an openness to all sound but making value

judgements as to what was acceptable. These value judgements were linked to his ideas that music was

about bettering oneself and were linked to an anti-commercialist spiritual outlook Half-intellectually and

half-sentimentally, when the war came along, I decided to use only quiet sounds. There seemed to be no

truth, no good,in anything big in society. But quieter sounds were like loneliness, or love or friendship.

Pemanent, I thought, values, independent at least from Life, Time and Coca-Cola (Kahn, 1997, p. 577)

Cages rejection of jazz has been taken up by George Lewis who argues that Cage was reflecting a white

Eurological perspective on Afrological music through a failure within white culture to understand black

Malcolm Atkins

Cage is dead

page 10 of 12

music (Lewis has also commented on how well acquainted African Americans are with the concept of

silence).

He asserts that Cage misunderstood improvisation and collective working in African American music

because he interpreted it through comparison to European improvisation in art music of the nineteenth

century such as of Liszt, Chopin or Paganini. Lewis argues that from the 1950s composers began to

experiment with open forms and with more personally expressive systems of notation (Lewis, 2004A, p

131 ff )and how this corresponds to the recognition of jazz as a valid art form.

Lewis sees improvisation within an Afrological perspective as involving collaboration to resolve agreed

problems as well as group communication. The heuristic element is in his view what experimental

composers have attempted to achieve in creating process based music which the performer explores. He

examples Alvin Lucier. In an Afterword to Improvised Music after 1950 he argues that contrary to the

composers protestations Luciers piece Vespers with its emphasis on analysis, exploration, discovery and

response to conditions becomes the purest, most utterly human form of improvisation, expressive of its

fundamental nature as a human birthright (Lewis, 2004B, p 170). If we accept Lewis view then the

African traditions of music making are closer in ideology to the philosophy that Cage espoused of

removing the ego from performance because of their basis in collective working. Perhaps Cage was far

more constrained by the legacy of European Romanticism than he was aware.

Conclusions

I have looked at a particular statement of Cage and explained its context and its obvious failings.

This is not to denigrate the performance of his work but it is to take up the questions he raised in his work

in his time and assess their relevance to ours.

The legacy of Cage is evident in so much work that continues to explore the questions he raised about how

we should structure sound, how far we should include everyday sound in constructed sound, what is the

purpose of music.

I have the following reservations about that legacy.

Cage was promoting a particular philosophical world view in all his work from 1952 onwards. At its worst

when I experience this as spiritual pretension in sound art (especially covers of work by Cage or

imitations) I feel patronised and bored. I can go for a walk and experience real sounds and the real world.

Why does someone need to show me how to do this ? The indirect nature of what can appear to be smug

superiority can be much more irritating than the direct spiritual message of composers such as Tavener and

Prt who could argue that they work in traditions that remove the ego anyway (Prt s refusal to write

anything different seems to confirm this)

The rejection of the legacy of Romanticism by Cage was a personal choice that reflected attitudes of his

time. The rejection of emotive qualities in music was significant in the avant-garde and in experimental

music for a long time. However I do not think we need to continue this any further. In improvised music I

still feel the presence of the non-idiomatic police those who seek a tough modernist sound world with no

unnecessary frills. However, to my mind, to deny the lyrical in musical expression is to lessen its scope.

Malcolm Atkins

Cage is dead

page 11 of 12

Further to this point, the composers who I would choose to listen to who come from the experimental

tradition are Feldman and Skempton (who I would see as the most important composer in Britain today).

Both of these composers can engage with the unfolding of line and the careful structuring of their work for

its emotive effect (without prescribing a particular emotion). I would describe their work as beautiful. In

this sense their aesthetic has gone far beyond the limitations that Cage set himself.

The rejection of improvisation and of African American traditions seems to be a serious failing in Cage.

Would it not have helped him sober his mind to try and understand the approaches to music of different

cultures ? An interesting example would be the Indonesian idea that a musical performance should be busy

rame. It allows no time for calm reflection but fulfils a significant social purpose.

Finally there is a danger in totally underestimating what is needed to create a musical work if Cages ideas

are followed without the discipline he showed. Cage followed a particular path but did it with total

dedication and concentration over a prolonged period of time. His engagement with sound was considered

and justified in endless debate and was reached from an understanding of a broader musical culture (even

if he rejected much of that). His debate and argument has helped set up a framework for unthinking

replication of his ideas (just as previously there has been unthinking repetition of classical, Romantic and

avant-garde ideas). However the danger with following Cage is that musicians lessen their allowed

vocabulary before they start creating music and have not the skill set that enabled Cage to make the

choices that he did.

Bibliography

Cage, J. (2004) Silence, London, Calder and Boyars.

Cott, J. (1963) John Cage Interviewed by Jonathan Cott [online] at

http://ubumexico.centro.org.mx/sound/cage_john/var/Cage-John_Interview_Jonathan-Cott_1963.mp3

(Accessed Sept 2013)

Fetterman, W. (1996) John Cages Theatre Pieces, London, Harwood.

The Holst Foundation An Open Letter to Sound and Music and Arts Council England[online] at

http://www.holstfoundation.org/index.php?pr=Open_Letter_to_SAM_and_ACE (Accessed Sept 2013)

Kahn, D. (1997). John Cage: Silence and silencing. The Musical Quarterly, 81(4), 556-598.

Lewis, G. (2004a) Improvised music after 1950:Afrological and Eurological Perspectives, in Fischlin, D.

and Heble, A., eds. The other side of nowhere: jazz, improvisation, and communities in dialogue, United

States, Wesleyan University Press, pp. 131-162.

Malcolm Atkins

Cage is dead

page 12 of 12

Lewis, G. (2004b) Afterword to Improvised music after 1950:The Changing Same, in Fischlin, D. and

Heble, A., eds. The other side of nowhere: jazz, improvisation, and communities in dialogue, United

States, Wesleyan University Press, pp. 163-172.

MacGilchrist, I. (2010) The Master and his Emissary, New Haven, Yale University Press.

Montague, S. (1985) John Cage at Seventy-Five: An Interview, American Music Vol. 3, no. 2

(Summer). 205-216.

Nyman, M. (1999) Experimental Music Cage and Beyond, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

Oliveros, P. (1996) Four Meditations for Orchestra, Deep Listening Publications

Ross, A.(2008) The Rest is Noise, London, Fourth Estate

Suler, J. (1997) Zen Stories to Tell Your Neighbours [online] at

http://users.rider.edu/~suler/zenstory/gutei.html (Accessed Sept 2013)

Volta, O. (1994) Satie Seen Through His Letters , London, Marion Boyars

You might also like

- Postcolonial Repercussions: On Sound Ontologies and Decolonised ListeningFrom EverandPostcolonial Repercussions: On Sound Ontologies and Decolonised ListeningJohannes Salim Ismaiel-WendtNo ratings yet

- Music 109: Notes on Experimental MusicFrom EverandMusic 109: Notes on Experimental MusicRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (5)

- John Cage - Experimental Music DoctrineDocument5 pagesJohn Cage - Experimental Music Doctrineworm123_123No ratings yet

- Kompositionen für hörbaren Raum / Compositions for Audible Space: Die frühe elektroakustische Musik und ihre Kontexte / The Early Electroacoustic Music and its ContextsFrom EverandKompositionen für hörbaren Raum / Compositions for Audible Space: Die frühe elektroakustische Musik und ihre Kontexte / The Early Electroacoustic Music and its ContextsNo ratings yet

- Breathless: Sound Recording, Disembodiment, and the Transformation of Lyrical NostalgiaFrom EverandBreathless: Sound Recording, Disembodiment, and the Transformation of Lyrical NostalgiaNo ratings yet

- Bibliography of James TenneyDocument5 pagesBibliography of James TenneyvalsNo ratings yet

- Banding Together: How Communities Create Genres in Popular MusicFrom EverandBanding Together: How Communities Create Genres in Popular MusicNo ratings yet

- Notes on John Cage's DiaryDocument2 pagesNotes on John Cage's Diarylaura kleinNo ratings yet

- Alvin Lucier: A CelebrationFrom EverandAlvin Lucier: A CelebrationAndrea Miller-KellerRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (2)

- Variations on the Theme Galina Ustvolskaya: The Last Composer of the Passing EraFrom EverandVariations on the Theme Galina Ustvolskaya: The Last Composer of the Passing EraNo ratings yet

- Morris-Letters To John CageDocument11 pagesMorris-Letters To John Cagefrenchelevator100% (1)

- Wagner's Relevance For Today Adorno PDFDocument29 pagesWagner's Relevance For Today Adorno PDFmarcusNo ratings yet

- Layers of Meaning in Xenakis' PalimpsestDocument8 pagesLayers of Meaning in Xenakis' Palimpsestkarl100% (1)

- Composing Intonations After FeldmanDocument12 pagesComposing Intonations After Feldman000masa000No ratings yet

- Aesthetic Technologies of Modernity, Subjectivity, and Nature: Opera, Orchestra, Phonograph, FilmFrom EverandAesthetic Technologies of Modernity, Subjectivity, and Nature: Opera, Orchestra, Phonograph, FilmNo ratings yet

- Awangarda: Tradition and Modernity in Postwar Polish MusicFrom EverandAwangarda: Tradition and Modernity in Postwar Polish MusicNo ratings yet

- InsideASymphony Per NorregardDocument17 pagesInsideASymphony Per NorregardLastWinterSnow100% (1)

- Sciarrino Solo Kairos PDFDocument29 pagesSciarrino Solo Kairos PDFPhasma3027No ratings yet

- Focal Impulse Theory: Musical Expression, Meter, and the BodyFrom EverandFocal Impulse Theory: Musical Expression, Meter, and the BodyNo ratings yet

- First Letters After Exile by Thomas Mann, Hannah Arendt, Ernst Bloch, and OthersFrom EverandFirst Letters After Exile by Thomas Mann, Hannah Arendt, Ernst Bloch, and OthersNo ratings yet

- 01 Cook N 1803-2 PDFDocument26 pages01 Cook N 1803-2 PDFphonon77100% (1)

- On Minimalism: Documenting a Musical MovementFrom EverandOn Minimalism: Documenting a Musical MovementKerry O'BrienNo ratings yet

- Varese - The Liberation of SoundDocument4 pagesVarese - The Liberation of SoundD'Amato AntonioNo ratings yet

- The Style Incantatoire in André Jolivet's Solo Flute WorksDocument9 pagesThe Style Incantatoire in André Jolivet's Solo Flute WorksMaria ElonenNo ratings yet

- An Introduction To Acoustic EcologyDocument4 pagesAn Introduction To Acoustic EcologyGilles Malatray100% (1)

- Interpretation and Computer Assistance in John Cage'S Concert For Piano and ORCHESTRA (1957-58)Document10 pagesInterpretation and Computer Assistance in John Cage'S Concert For Piano and ORCHESTRA (1957-58)Veronika Reutz DrobnićNo ratings yet

- Nostalgia for the Future: Luigi Nono's Selected Writings and InterviewsFrom EverandNostalgia for the Future: Luigi Nono's Selected Writings and InterviewsNo ratings yet

- Varese's Vision of Electronic MusicDocument2 pagesVarese's Vision of Electronic MusicSanjana SalwiNo ratings yet

- Johann Sebastian Bach: The Organist and His Works for the OrganFrom EverandJohann Sebastian Bach: The Organist and His Works for the OrganNo ratings yet

- Adorno Radio SymphonyDocument10 pagesAdorno Radio SymphonyNazik AbdNo ratings yet

- Feldman Paper2Document23 pagesFeldman Paper2Joel SteinNo ratings yet

- Silence: Lectures and Writings, 50th Anniversary EditionFrom EverandSilence: Lectures and Writings, 50th Anniversary EditionRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (14)

- Garrett Pluhar-Schaeffer - Forgetting Music. On Morton FeldmanDocument95 pagesGarrett Pluhar-Schaeffer - Forgetting Music. On Morton FeldmanquietchannelNo ratings yet

- Kahn 1995Document4 pagesKahn 1995Daniel Dos SantosNo ratings yet

- Other Minds 15 Program BookletDocument36 pagesOther Minds 15 Program BookletOther MindsNo ratings yet

- A Guide To Morton Feldman's Music - Music - The Guardian PDFDocument4 pagesA Guide To Morton Feldman's Music - Music - The Guardian PDFEvi KarNo ratings yet

- Jazz Chord Licks Lofi Hip-Hop Guitar Style Tab NotationDocument1 pageJazz Chord Licks Lofi Hip-Hop Guitar Style Tab NotationChris TmasNo ratings yet

- Review of G Sanguinetti "The Art of Partimento"Document9 pagesReview of G Sanguinetti "The Art of Partimento"Robert Hill100% (1)

- Contemporary Orchestration TechniquesDocument3 pagesContemporary Orchestration TechniquesAdriano SargaçoNo ratings yet

- II-V-I and The Diatonic Functionality - The Jazz Piano SiteDocument6 pagesII-V-I and The Diatonic Functionality - The Jazz Piano SiteMbolafab RbjNo ratings yet

- Anderson - Julian-Seductive SolitaryDocument5 pagesAnderson - Julian-Seductive SolitaryKristupas BubnelisNo ratings yet

- TransFormula Series Ebook PDFDocument5 pagesTransFormula Series Ebook PDFGüray Özcana100% (6)

- 8-Bar Composition FormulaDocument3 pages8-Bar Composition FormulaMatt BallNo ratings yet

- The Five Facets of Music TeachingDocument75 pagesThe Five Facets of Music TeachingAbegail DimaanoNo ratings yet

- Glossary of MusicalDocument17 pagesGlossary of MusicalKim Enero BustaliñoNo ratings yet

- The Unaccompanied Choral Works of Vytautas Mi - Kinis With Texts by PDFDocument113 pagesThe Unaccompanied Choral Works of Vytautas Mi - Kinis With Texts by PDFviagensinterditas0% (1)

- Canon in D : ViolinDocument3 pagesCanon in D : ViolinHamedNahavandiNo ratings yet

- Improvisation Rubric l3 s2Document2 pagesImprovisation Rubric l3 s2api-548014771No ratings yet

- The AP Exam in Music TheoryDocument20 pagesThe AP Exam in Music Theorymyjustyna100% (1)

- WritingDocument2 pagesWritingKhairul AnwarNo ratings yet

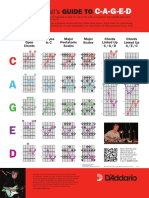

- Fa CagedDocument1 pageFa CagedwergwNo ratings yet

- References for Music DocumentsDocument4 pagesReferences for Music DocumentsAleff PassosNo ratings yet

- Jazz Guitar Chord Exercises - GuitarworldDocument9 pagesJazz Guitar Chord Exercises - GuitarworldJoséG.ViñaG.No ratings yet

- How To Use: The Caged SystemDocument7 pagesHow To Use: The Caged SystemLorenzo BuzzottaNo ratings yet

- Pentatonic Shapes 2020b Treble InstrumentsDocument41 pagesPentatonic Shapes 2020b Treble Instrumentsmaurizio bassi100% (3)

- GesturalDocument49 pagesGesturalPhil DonnellyNo ratings yet

- Piano Suspended Chords GuideDocument4 pagesPiano Suspended Chords Guideraduseica100% (1)

- Jazz ScalesDocument6 pagesJazz ScalesUr RaNo ratings yet

- Music 6 DLP InsetDocument5 pagesMusic 6 DLP InsetRenalyn RedulaNo ratings yet

- Becker Marianne 1979-001Document99 pagesBecker Marianne 1979-001ASNo ratings yet

- Calypso Minor Piano, Lead Et GrilleDocument1 pageCalypso Minor Piano, Lead Et GrillelomorNo ratings yet

- Elvis Presley - Cant Help Falling in Love BassDocument4 pagesElvis Presley - Cant Help Falling in Love BassNicola ZilianiNo ratings yet

- Cadence in MusicDocument6 pagesCadence in MusicSeyit YöreNo ratings yet

- 10 Emotional and Sad Chord Progressions You Should Know - LANDR BlogDocument17 pages10 Emotional and Sad Chord Progressions You Should Know - LANDR BlogWayne WhiteNo ratings yet

- Canon in D: (LarghettoDocument2 pagesCanon in D: (Larghettoregulocastro5130No ratings yet

- MU 1213-01 - Music Theory I PDFDocument5 pagesMU 1213-01 - Music Theory I PDFstefan popescuNo ratings yet