Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Content Server

Uploaded by

hanina123Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Content Server

Uploaded by

hanina123Copyright:

Available Formats

Indonesia and the Malay World, Vol. 30, No.

86, 2002

JAWI SPELLING AND ORTHOGRAPHY: A BRIEF

REVIEW

E. ULRICH KRATZ

The history of the spelling of Malay and other Indonesian languages is long and

fascinating. Understandably, it is tied in closely with the history of the scripts used for

the writing of Malay over the centuries and, given the differing nature of the scripts in

use at one time or another, they have had different impacts on Malay spelling. From

using forms of the Pallava and Nagari scripts, Malay moved on to Jawi, a modi ed form

of the Arabic alphabet, and then to Rumi, the Roman or Latin script. Today, the Latin

script is used predominantly throughout the Malay world, notwithstanding the powerful

association of Jawi with Islam and hence with Malay identity.

Studies of individual examples of writing aside, our general knowledge of the

development of these scripts in the Malay world prior to the introduction of printing

remains uneven, since their presence tends to be taken for granted. Scripts are prone to

be looked at as awed images of their foreign ancestors, and they have rarely been

studied in their own right, but merely as ancillaries to other studies or for other purposes.

Spelling systems are equally judged with a view to consistency and conformity, to

spelling law and order.

Well-known and probably still indispensable is the extensive tabling work by Holle

(1882) which retraces the then known evidence of inscriptions, manuscripts, and other

objects with writing in Indonesian languages on them. Then there is the very important

study by de Casparis (1975), who, for the rst time, gives us a deeper historical

understanding of the development of Pallava and Nagari scripts in the context of Island

South East Asia. More recently, the study by Kozok (1999) offers an important and

detailed look at the development of the Batak script as a major example of the Pallava

transformation. Comparable studies for other Indonesian forms of the Pallava script are

still lacking.

Rumi writing and spelling were most recently discussed by Vikr (1988) in exhaustive

detail. He provides a succinct survey of their development and the many diverging and

prescriptive attempts at standardizing the spelling, rst within the spheres of in uence of

the Dutch and the British, and then in the post-colonial Malay world. Post-colonial

efforts have eventually led to (almost) one system of spelling of Malay and Indonesian

words in the Latin script; the jointly-agreed common system is known, rather confusingly, by different namesas ejaan yang disempurnakan (or perfected spelling) in

Indonesia, and as ejaan baku (or standard spelling) in Malaysia, Brunei Darussalam and

Singapore.

Of the three writing systems, Indian, Middle Eastern, and Roman, Jawi remains the

least studied and documented in its own right with regard to actual writing and spelling.

Even its very name, Jawi, has long remained open to speculation (Roolvink, 1975).

Leaving aside earlier Arabic inscriptions on tombstones, the use of Jawi for Malay has

been in evidence since the days of the Trengganu Stone inscription. This, according to

Muhammad Naguib al-Attas (1970), dates from the early fourteenth century and provides

ISSN 1363-9811 print/ISSN 1469-838 2 online/02/860021-06 2002 Editors, Indonesi a and the Malay World

DOI: 10.1080/1363981022013464 7

22

E. Ulrich Kratz

evidence of the nalisation of the Jawi alphabet (Omar bin Awang, 1985). Then there

is the physical evidence of manuscripts from the sixteenth century onwards (Shellabear,

1898). We should remind ourselves however of the words of de Casparis (1975:72), that

behind the visible evidence of objects preserved, there is the invisible preceding and

contemporaneous history of a much larger writing tradition which has been lost, since

it had been recorded on perishable materials.

A reason for the lack of a deeper academic interest in Jawi writing and spelling itself

may have been the view that, irrespective of the local additions, Jawi was merely a

borrowing from Arabic (Shellabear, 1901). Furthermore, its Malay users appeared to

remain rather inept and inexperienced in its use. After all, there was no calligraphy to

boast about as in, say, Mughal India, Persia, the Ottoman Empire, or the Arabic

heartlands, all places with which the Malay world had been in sustained contact over

centuries. In addition, there was no proper system of spelling rules and norms, it

seemed, and instead, Malay scribes were said to write down randomly and to the best

of their ignorance what they had heard. By and large, any deviation and variation from

a postulated standard of spelling was seen as the result of scribal error and incompetence,

and great efforts were made to force Jawi spelling into a Procrustean bed of presumed

rules and standards. These rules and standards, however, originated more in the

perceived needs of European missionaries and colonial administrators who, ironically,

wrote in languages whose own rules of spelling were far from consistent.

But does this request for norms and standards really do justice to the evidence of the

Malay manuscript tradition, and was there really no system underlying the perceived

confusion?

What strikes the student of the Jawi writing tradition at a glance is the almost total

lack of historicity in the treatment of the Jawi spelling. Various discussions notwithstanding (Shellabear, 1901; Kang, 1986; Harahap, 1992; Hashim bin Musa, 1994; Amat

Juhari Moain, 1996), and not unlike the case of traditional Malay language and literature

themselves, Jawi spelling has been treated mostly in an unhistorical way. To put it most

negatively, this appears due to the perception that there have been only few and

insigni cant changes,an exempli cation of the fact that the Oriental is slow to

change, as Shellabear (1901:76) states.

Hand in hand with the view which sees Jawi spelling as we know it as xed and

nalized yet ineptly written by scribes, goes the normative attitude to Jawi spelling,

which treats its manifestations as spelt either correctly or incorrectly. Correct and

incorrect, that is, according to the normative and prescriptive criteria of European judges,

who not only endeavoured to standardize the spelling of Malay in Rumi, but also with

it that of Jawi; and correct or incorrect according to those who regretted that Jawi was

not really used as one would use the Arabic script and that Malay was not really spelt

as one would spell the Arabic language.

Lest one should think that the obsession with rules and norms was merely a

preoccupation of Islamic teachers and Christian missionaries and colonial administrators

cum scholars, let it be recalled that in Malaysia today, long after missionaries and

colonial administrators have gone, there are at least three different prescriptive spelling

systems of Jawi which compete with each other for exclusive recognition. Each with its

own political agenda, they are that of the Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka which is a version

of the Zaba spelling, that of the Utusan newspaper, and that of the Pusat Dakwah. To

this might be added the system proposed and (only) used by Kang (1986).

Jawi, as used in the Malay world, is the modi ed Arabic script developed from its

Persian form. Perceptively, early Malay-speaking linguists had developed the Perso-

Jawi spelling and orthography: a brief review

23

Arabic script further to accommodate speci c Malay phonemes. This they did brilliantly,

even if Persian linguists had shown them the way when they had adapted the Arabic

script to their own needs. It seems highly unlikely that Jawi was introduced and used

exclusively by Arabs initially, and that only when it was used by non-native writers of

Arabic did its spelling become confused (Shellabear, 1901). One can assume that those

developing the Jawi script for use with Malay had been familiar with the Pallava script

and some of its South-East Asian variants as is, for example, illustrated by Ricklefs

(1976) and mentioned by Collins (1997:53).

Once established, Jawi bridged the various Malay dialects and usages in the palaces,

the markets, and the religious schools much better than Rumi would ever do. Rumi took

away the freedom of the speakers to pronounce and speak Malay in the way which they

were used to locally, and it broke the shared written link. With its insistence on spelling

conventions which were in uenced by Dutch or English, Rumi helped to divide the

Malay-speaking community, whereas the major perceived shortcoming of Jawi as written

in the Malay world, namely that of not presenting all vowels, was, I suggest, in fact its

major strength. If one knew Malay, one did not need the vowel signs, which tended only

to be used when there was a possibility of ambiguity and misunderstanding for the reader

in the mind of the scribe.

Only one study to date deals with the history of Jawi spelling as a process of

development and not one of deterioration and deviation. The study by Kang (1986)

suggests that Malay spelling has developed in three stages: period A between 1300 and

1600 which sees the disappearance of Arab words and other elements of the Arabic

language and writing; period B between 1600 and 1900 which witnesses the emergence

and presentation of at least one vowel in each word; and period C from 1900 onwards

which sees the continued advance of all vowels other than alif, with the exception of

some fossilized words which retain their Arabic spelling (Kang 1986:98). This may be

so, but it remains doubtful that Kangs criteria really go to the heart of the problem as,

it would seem, his references are less to the evidence of the Malay manuscripts

themselves than to European descriptions and characterizations of their nature and

speci cs. We have known for some years, however, that editions of Malay texts prepared

in reference to the European tradition of classical philology tell us more about their

editors perception of Malay than about the manuscripts themselves (Kratz 1981). By

referring exclusively to Arabic, as Shellabear does, Kang also seems to ignore the

importance of Persian with which Malay shares many of its Arabic borrowings.

Quite different from Kangs proposal, which attempts to place and date expressions of

the Jawi script historically in three stages, is the recent approach by Tol (2001), which

looks at writing styles and shapes of letters. Tol suggests using de nitive criteria for

describing actual examples of Jawi writing, in accordance with established practice

elsewhere, where the Arabic script in its various manifestations has been studied

carefully and systematically. Tol exempli es his suggestions by looking at the writing

style of a particular writer.

This is an important suggestion which will contribute signi cantly to a better

chronology of Jawi writing and, in turn, of spelling features. Yet it does not help to, nor

is it meant to, address the notion of the inability of Malay scribes to spell Malay

properly and according to some presumed rules, the perceived lack of a binding

orthographic system, nor the fateful habit of many an editor of correcting and perfecting

variations in Jawi spelling in accordance with some preconceived notions of correct and

incorrect spelling. There is no argument that Jawi texts contain scribal errors, but one

needs to distinguish obvious mistakes from any possible variations in spelling. One can,

24

E. Ulrich Kratz

in the Malay writing tradition, discern very strong conventions of how and how not to

write. This is acknowledged by many. One can also see a considerable effort to get it

right when one looks, for example, at the great effort at accuracy in the reproduction

of European names by scribes of Malay (an accuracy which is not matched by editors

who mutilate these names again in their transcriptions). The evidence shows that there

did not exist one single normative system for spelling Jawi (just as there are no

written-out Malay poetics in the prescriptive sense) but, it must be stressed, most words

are only ever spelled in one way. Changes in spelling, i. e. the differing spelling of any

given word, usually follows a recognizable pattern. It is the varying spelling of these

words, that fall outside the general consensus of how words are to be spelt, which gave

rise to the condescending attitude towards the Malay scribal tradition at large.

Wilkinson, who was probably the most sympathetic scholar to comment on the

spelling and writing of Jawi, wrote:

The vast majority of writers, however, trouble themselves very little

about theories of spelling. They spell as they have been taught to spell

without considering what is consistent and what is not. The student of

Malay will consequently do well as to waste no time over the study of

orthography. The more widely he reads, the clearer will his perception

be of the futility of either expecting uniformity or of enforcing it.

(Wilkinson, 1903:712).

Sound as Wilkinsons advice remains to this day, the question stands as to why there is

no uniformity and why there is variation and inconsistency in the spelling of Malay. I

suggest that any answer to this question will help our understanding of the dynamics of

cultural exchange in the Malay world at a level not touched by many of the generalizations encountered to date.

To nd a possible explanation, one has to go back to de Casparis suggestion that

there has been a continuous history of writing which is not revealed by the sources (de

Casparis, 1975:73). One has to remember that Jawi did not come out of nothing and that

prior to its introduction people were already familiar with the Pallava and Nagari scripts

which, unlike the Arabic script but similar to the Latin one, spelt out each phoneme,

consonant and vowel. The Pallava script accommodated the basic structure of the

Austronesian word of consonantvowelconsonantvowel(consonant) and its pronunciation extremely well, and it stands to reason that Malay scribes adapting to the new

writing system of Jawi would have wanted to continue to express the speci c character

of Malay and speci c Malay phonemes in the new Arabic-derived script. This they did,

rstly by adding more letters to the alphabet, and secondly, by adhering to a way of

spelling which was closer to the one they and their readers were used to from writing

and reading forms of the Pallava script. Naturally, there was opposition from those who

wanted to adopt and apply the new system in its totality in order to express their new

faith down to the letter. It is in this that the lack of uniformity has its roots, and where

one can observe the struggle between old and new, between Pallava principles and the

Arab way of things, expressed in the spelling of Malay words, either indigenous, or

borrowed from Sanskrit, or more recently introduced from Arabic and Persian.

Quite often there is a pragmatic and practical compromise, dubbed inconsistency by

European critics and ideological purists alike. Ultimately, however, the conclusion has

to be drawn that the way traditional Malay has been spelt is less an indicator of a lack

of application of Malay scribes to the new culture and religion, but more an indicator of

Jawi spelling and orthography: a brief review

25

the strength and the deep roots of the previous writing tradition within Malay culture in

general. Malay spelling as we know it from the manuscript tradition then re ects the

con ict between an older Indian and a more recent Islamic tradition.

The arrival of the Latin script cannot have helped the process of agreeing on a single

form of spelling, since it threw up again the questions raised when Jawi was rst

introduced and may have made scribes want to experiment, as did Zaba or Major Dato

Haji Mohd. Said Sulaiman, or the journal Dian (Amat Johari Moain, 1996: 70101).

This con ict, I suggest, still remains unresolved to this day, if the present Malaysian

disagreement about the right way to spell Jawi is placed into its historical context.

Today, it is no longer the Pallava system which competes with a pure Arabic, i.e. the

perceived Islamic, way of spelling, but it is the continuing interference of Rumi which

keeps the con ict going. What is ignored however in this struggle of the ideologues and

purists is the successful compromise, which had been achieved over centuries, and which

aimed to give the Malay language and its actual usage its own. Yet this was a

compromise which had served communication among all Malays, whatever their dialect

and whatever their learning, so well in the past and which had gained them the respect

of the Europeans who made contact with them (Collins, 1997:52).

There are important ideas and thoughts in many of the studies of Jawi spelling and

writing. The time has come however to look at the history and nature of Jawi spelling

and writing with a fresh eye and to rid oneself from the assumptions and presumptions

of past scholarship, lest the negative and dismissive perception of the Malay spelling

tradition is found out to be, yet again, the result of the pars pro toto approach to all

things Malay, which students of Malay are not unfamiliar with.

SOAS

Thornhaugh Street

Russell Square

London WC1H 0XG

References

Amat Juhari Moain. 1996. Sejarah aksara Jawi. Kuala Lumpur: Dewan Bahasa dan

Pustaka.

Casparis, J. G. de. 1975. Indonesian palaeography : a history of writing in Indonesia

from the beginnings to c. A.D. 1500. Leiden/Koln: Brill. (Handbuch der Orientalistik,

3.4.1.)

Collins, J.T. 1997. Ciri-ciri bahasa Melayu abad ke-17. (In Perpustakaan Negara

Malaysia (ed.). Tradisi penulisan Melayu. Kuala Lumpur: Perpustakaan Negara

Malaysia, 5170.)

Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka. 1988. Pedoman transliterasi huruf Arab ke huruf Rumi.

Kuala Lumpur: Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka.

Harahap, Darwis. 1992. Sejarah pertumbuhan Bahasa Melayu. Pulau Pinang: Universiti

Sains Malaysia.

Hashim bin Musa. 1994. Sejarah awal tulisan Jawi. Alam Melayu, 2, 128.

Hashim [bin] Musa. 1997. Sejarah awal kemunculan dan pemapanan tulisan Jawi di

Asia Tenggara. (In Perpustakaan Negara Malaysia (ed.). Tradisi penulisan Melayu.

Kuala Lumpur: Perpustakaan Negara Malaysia, 149.)

Holle, K. F. 1882. Tabel van oud- en nieuw- Indische alphabetten. Batavia en s Hage:

W. Bruining en Nijhoff.

26

E. Ulrich Kratz

Kang, Kyong Seock. 1986. Perkembangan Jawi dalam masyarakat Melayu. Kuala

Lumpur: Datuk Syed Kechick bin Syed Mohamed al-Bukhary.

Kozok, U. 1999. Warisan leluhur. Sastra lama dan aksara Batak. Jakarta: Ecole

Francaise dExtreme-Orient/KPG.

Kratz, E.U. 1981. The editing of Malay manuscripts and textual criticism. Bijdragen tot

de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde, 137(23), 22943.

Lewis, M.B. 1954. A handbook of Malay script. London: Macmillan and Co. Ltd.

Mohd. Nor bin Ngah. 1982. Kitab Jawi: Islamic thought of the Malay Muslim scholar.

Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies.

Muhammad Naguib al-Attas. 1970. The correct date of the Trengganu Stone inscription.

Kuala Lumpur: Muzium Negara.

Nik Hassan Shuhaimi Nik Abdul Rahman (ed.). 1999. Early history. Singapore: Editions

Didier Millet. (The Encyclopedia of Malaysia, 4.) [First edition 1998.]

Omar bin Awang. 1985. The Trengganu inscription as the earliest known evidence of the

nalisation of the Jawi alphabet. (In Lutpi Ibrahim (ed.). Islamika. Kuala Lumpur:

Muzium Negara untuk Jabatan Pengajian Islam Universiti Malaya, 18996.)

Perpustakaan Negara Malaysia (ed.). 1997. Tradisi penulisan Melayu. Kuala Lumpur:

Perpustakaan Negara Malaysia.

Ricklefs, M.C. 1976. Banten and the Dutch in 1619: six early Pasar Malay letters.

Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, 39(1), 12836.

Ronkel, P.S. van. 1928. Het Maleische schrift. Weltevreden: [Landsdruk kerig]

Roolvink, R. 1975. Bahasa Jawi: de taal van Sumatra. Leiden: Universitaire Pers.

Shellabear, W.G. 1898. An account of some of the oldest Malay MSS now extant.

Journal of the Straits Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, 31, 10752.

Shellabear, W.G. 1901. The evolution of the Malay script. Journal of the Straits Branch

of the Royal Asiatic Society, 36, 75135.

Siti Hawa Haji Salleh. 1997. Alat tulis Melayu tradisional. (In Perpustakaan Negara

Malaysia (ed.). Tradisi penulisan Melayu. Kuala Lumpur: Perpustakaan Negara

Malaysia, 21116.)

Tol, R. 2001. Master scribes: Husain bin Ismail, Abdullah bin Abdulkadir Munsyi, their

handwriting and the Hikayat Abdullah. Archipel, 61, 11538.

Vikr, L.S. 1988. Perfecting spelling. Dordrecht: Foris. (Verhandelingen van het

Koninklijk Instituut voor Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde , 133.)

Wan Mohd. Shaghir Abdullah. 1997. Tulisan Melayu/Jawi dalam manuskrip dan kitab

bercetak: suatu analisis perbandingan. (In Perpustakaan Negara Malaysia (ed.).

Tradisi penulisan Melayu. Kuala Lumpur: Perpustakaan Negara Malaysia, 87110.)

Wilkinson, R. J. 1985. A classic Jawi-Malay-English dictionary. Melaka Alaia: Baharudinjoha. [First edition 1903.]

Zaba. 1928. Some facts about Jawi spelling. Journal of the Malay Branch of the Royal

Asiatic Society, 6(2), 81104.

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Blame It Bath Truth AboutDocument4 pagesBlame It Bath Truth Abouthanina123No ratings yet

- ExtDocument4 pagesExthanina123No ratings yet

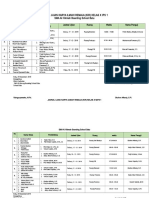

- Academic Sessions 2014-2015 UitmDocument2 pagesAcademic Sessions 2014-2015 UitmsilentsioNo ratings yet

- Oleh: Nang Naemah Nik DahalanDocument18 pagesOleh: Nang Naemah Nik Dahalanhanina123No ratings yet

- A6 SulaimanDocument21 pagesA6 Sulaimanhanina123No ratings yet

- Fear of The Jawi Syndrome New Straits TimesDocument4 pagesFear of The Jawi Syndrome New Straits Timeshanina123No ratings yet

- 105 H10251Document5 pages105 H10251hanina123No ratings yet

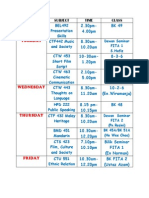

- Course Info - March 2013Document7 pagesCourse Info - March 2013hanina123No ratings yet

- Public Speaking Assignment IDocument4 pagesPublic Speaking Assignment Ihanina123100% (1)

- Public Speaking Assignment 1Document2 pagesPublic Speaking Assignment 1hanina123No ratings yet

- Public Speaking Assignment IDocument4 pagesPublic Speaking Assignment Ihanina123100% (1)

- Schedule Part 2Document1 pageSchedule Part 2hanina123No ratings yet

- Preparation For Presentation Outline 3Document1 pagePreparation For Presentation Outline 3hanina123No ratings yet

- Depleted Findings Value in Career Planning Shows That The StudentsDocument2 pagesDepleted Findings Value in Career Planning Shows That The Studentshanina123No ratings yet

- Triple TalaqDocument28 pagesTriple TalaqRahul BarnwalNo ratings yet

- Surah Al Baqarah (2:153) - Medical and Psychological Benefits of Salat and SabrDocument5 pagesSurah Al Baqarah (2:153) - Medical and Psychological Benefits of Salat and SabrMuhammad Awais Tahir100% (1)

- Supplications For HajjDocument14 pagesSupplications For Hajjd-fbuser-49116512No ratings yet

- Aqeedah of Four ImamsDocument3 pagesAqeedah of Four ImamsAndra VasileNo ratings yet

- Chapter - 72 - Surah Al-Jinn Tafsir-Ibn-Kathir - 5333Document21 pagesChapter - 72 - Surah Al-Jinn Tafsir-Ibn-Kathir - 5333Sadiq HasanNo ratings yet

- Downfall of Muslim Society in PakistanDocument6 pagesDownfall of Muslim Society in PakistanSalman AhmadNo ratings yet

- Cut Out QR Tahun 5Document40 pagesCut Out QR Tahun 5MASTURA BINTI ABD MANAF MoeNo ratings yet

- Bulleh Shah If You Wish To Be A Ghazi Take Up Your Sword Before Killing The Kafir You Must Slaughter The SwindlerDocument20 pagesBulleh Shah If You Wish To Be A Ghazi Take Up Your Sword Before Killing The Kafir You Must Slaughter The Swindlerscparco100% (2)

- Bush JosephThesis PDFDocument92 pagesBush JosephThesis PDFpetronemicheleNo ratings yet

- Cow Slaughter and Hindu Persecution in The Indian Subcontinent: A Short HistoryDocument58 pagesCow Slaughter and Hindu Persecution in The Indian Subcontinent: A Short HistorynayasNo ratings yet

- Kitab Aur Iski EhmiatDocument16 pagesKitab Aur Iski EhmiatNisarv gkhanNo ratings yet

- Economy Prosperity EssayDocument4 pagesEconomy Prosperity EssaySolitaryReaperNo ratings yet

- 4 Marks QuestionsDocument5 pages4 Marks QuestionsHaris khan81% (21)

- Hadith & SunnahDocument127 pagesHadith & SunnahMuhammad Omar100% (1)

- Class IX English Book NotesDocument13 pagesClass IX English Book NotesMuhammad AyanNo ratings yet

- List of ThesisDocument44 pagesList of Thesisali5muhammadNo ratings yet

- JADWAL UJIAN KARYA ILMIAH REMAJA NewDocument3 pagesJADWAL UJIAN KARYA ILMIAH REMAJA NewGhufron AffandyNo ratings yet

- Siddiqui - Book ReviewDocument6 pagesSiddiqui - Book Reviewtushar vermaNo ratings yet

- Iqbals Ego PhilosophyDocument23 pagesIqbals Ego PhilosophyAli\\No ratings yet

- PDF Wahhabi Doctrine and Its DevelopmentDocument8 pagesPDF Wahhabi Doctrine and Its DevelopmentPatryk OsiewałaNo ratings yet

- Master of Ceremony'S Speech: Reciting The PrayerDocument5 pagesMaster of Ceremony'S Speech: Reciting The PrayerMaisarah Abdul JalalNo ratings yet

- Indeed This Knowledge Is The DeenDocument4 pagesIndeed This Knowledge Is The DeenDawah-tu-Salafiyyah Sisters Book ClubNo ratings yet

- A Guideline To TranslationDocument294 pagesA Guideline To TranslationMohamed Abulinein100% (1)

- The EloquenceDocument37 pagesThe Eloquenceapi-3761806100% (2)

- 40 Advices of Shaykh Abd Al Qaadir PDFDocument52 pages40 Advices of Shaykh Abd Al Qaadir PDFAtique SiddiquiNo ratings yet

- Do The Ash'aris Believe That The Apparent Meanings of The Qur'an Are Kufr / Unbelief?Document1 pageDo The Ash'aris Believe That The Apparent Meanings of The Qur'an Are Kufr / Unbelief?takwaniaNo ratings yet

- Preservation of The Quran.Document6 pagesPreservation of The Quran.Mikel AlonsoNo ratings yet

- Prayers of The ProphetsDocument9 pagesPrayers of The ProphetsJamal Uddin ZiaNo ratings yet

- Best Sample Arabic Literature HistoryDocument8 pagesBest Sample Arabic Literature Historyerine5995No ratings yet

- 30 Hadith For Children 2Document67 pages30 Hadith For Children 2Ajaz AhmadNo ratings yet