Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Global Virtual Teams A Human Resource Capital Architecture

Uploaded by

OscarOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Global Virtual Teams A Human Resource Capital Architecture

Uploaded by

OscarCopyright:

Available Formats

Int. J.

of Human Resource Management 16:9 September 2005 1583 1599

Global virtual teams: a human resource

capital architecture

Michael Harvey, Milorad M. Novicevic and Garry Garrison

Abstract As organizations continue to globalize their operations, it will become evident

that most organizations do not have the resources to fully man operations throughout the

world. Therefore, management will be examining organizational options that reduce the

demand on an already depleted pool of global managers. One of the options being

examined by companies is the global virtual team (GVT). These complex teams are being

considered as a bridge mechanism to allow multinational organizations to expand rapidly

without taxing present global managerial skills. This paper uses a theoretical foundation

based upon competency theory as the motivation for the formation of GVTs and to explain

how they function. Four critical capitals (i.e. human, social, political and cross-cultural)

are deemed to be essential for effectiveness of GVT and are discussed in the paper. In

addition, a process for assessing the stock of capital in a GVT team is also developed in the

paper.

Keywords Global virtual teams; human capital; social capital; political capital; crosscultural capital; management of global virtual teams.

The growing popularity of inter-organizational alliances, combined with the growing tendency

to flatten organizational structures and globalization, has accelerated the need for firms to coordinate activities that span geographic, as well as, organizational boundaries through the use of

global virtual teams.

(Townsend et al., 1998)

Introduction

Rapid globalization, disruptive technological innovations and radical deregulation have

profiled a new competitive landscape in a global context (Lei et al., 1996). This novel

performance environment requires strategic flexibility of global organizations generally

and their management human resource systems in particular (Zander and Kogut, 1995).

Global strategic flexibility augments the importance of human resource heterogeneity,

their supporting HR systems, and their managing architecture (Lepak and Snell, 2002).

The development of such HR architecture and HR systems should be conducive to

the effectiveness of global virtual teams (GVTs) in terms of their contribution to the

intellectual capital base of the firm.

The HR systems and architecture enabling GVTs to function as a knowledge agent of

the firm allow the firm to maintain a degree of flexibility in its structure and permits

Michael Harvey, School of Business Administration, University of Mississippi, Mississippi 38766,

USA (tel: 662 915 5830; fax: 662 915 5820; e-mail: mharvey@bus.olemiss.edu).

The International Journal of Human Resource Management

ISSN 0958-5192 print/ISSN 1466-4399 online q 2005 Taylor & Francis

http://www.tandf.co.uk/journals

DOI: 10.1080/09585190500239119

1584 The International Journal of Human Resource Management

feasible restructuring of its interconnected relationships within and outside its global

networks on an on-going basis (Poppo, 1995). The unexamined issue this paper addresses

is what specific HR systems and architecture are needed not only to develop GVTs into

intelligent agents of knowledge creation and transfer across multiple projects within the

flexible global organization, but also to create an effective HR capital base capable of

contributing to the overall intellectual capital of the firm. Because such architecture

could be relevant to the firm dynamic capabilities derived from a GVT context, it is

imperative to determine the means to gain and maintain capital in a GVT.

The purpose of this paper is to examine the various types of HR capital that are

accumulated at a GVT level and to propose a programme of assessing HR capital in these

teams. First, a competency based view of HRM for GVTs is presented and related to the

HR architecture of the firm. Second, the four components of the HR capital (i.e. human,

social, political and cross-cultural) are discussed to explain how they are engendered by

the utilization of GVTs. Finally, a programme of assessing and improving the HR capital

architecture of GVTs is proposed.

Developing the concept of global virtual teams

Henry and Hartzler (1998: 78) define virtual teams as: Teams of people who work

closely together even though they are geographically separated and may reside in

different time zones throughout various parts of the world. Additionally, virtual teams

can be characterized as transitory structures, since membership is often temporary and

frequently requires members to participate in multiple teams when new tasks emerge

(Scott and Einstein, 2001). Virtual teams prove to be a viable asset in organizations as

they tend to increase productivity, flexibility, dynamism and can adapt to a wide variety

of task environments (Townsend et al., 1998). GVTs are teams that are used to impart

these advantages to organizations competing in a global context.

Although the potential for GVT appears to be promising, there are fundamental

socio-technical problems inherent within these teams, since they are characterized as

being comprised of both geographically and organizationally dispersed team members

who communicate primarily via computer-mediated communication (CMC) (Daft and

Lengel, 1986). Therefore, effective collaboration can be much more difficult to develop

and maintain than collaboration found in conventional team structures (Townsend et al.,

1998). In addition, the basic social foundation (i.e. social, political and cultural capital)

may be very difficult to develop in a GVT context and even more problematic to maintain

in the fluid context of GVTs.

The premise behind the development of GVTs is to tap the abilities and creativity of

people distributed throughout the organization and to culminate individual expertise that

spans organizational boundaries culminating in the efforts of a GVT (Townsend et al.,

1998). It is a commonly held belief that these temporary teams allow global managers to

handle a greater number of projects that may be more contextual and complex than other

organizational configurations without the costs and time associated with employee travel

(Nemiro, 2001; Potter et al., 2002). Fundamentally, the success of GVTs is similar to the

practices of conventional, face-to-face teams, but without the physicality associated with

conventional teams. In fact, GVTs dominant mode of communication may be through

the use of telecommunications and various information technologies used to accomplish

organizational goals (Townsend et al., 1996).

Although GVTs show enormous promise for global organizations, opportunities for

non-conformance and dysfunctional team activities/performance are always present.

Some of the complexities with this global collaboration effort are the difficulties working

Harvey et al.: Global virtual teams 1585

with others not only from differing cultures, but also, with others from differing

functional backgrounds (Jarvenpaa et al., 1998; Townsend et al., 1998). Second, the

transitory nature of virtual teams means that members can participate in multiple teams

simultaneously. This reduces the ability for GVT members to have the opportunity to

build social/cultural capital within the team. These temporary situations make the reward

system and maintenance of the social operating procedures increasingly difficult,

especially since virtual teams are short-lived, which is recognized by the members prior

to entering the team (Hatch, 1997). Third, the ability to measure individual effort or job

performance is likely to be difficult to assess in GVTs because hierarchical and

bureaucratic controls may be non-existent or lack the ability to monitor these situations

effectively (Bal and Foster, 2000). Finally, virtual meetings lack the physical cues

present in face-to-face meetings, making it difficult if not nearly impossible for GVT

members to observe those behaviours used to establish informal rules or norms, thereby

increasing the opportunities for misunderstanding and non-conformance within the

confounds of the team (Finholt and Sproull, 1990).

A competency based view of HRM for global virtual teams

A competency based view of organizations competing on innovative teamwork in a global

context posits that multiple competencies at different phases of value creation process operate

interdependently, thus creating the potential to generate a sustained competitive advantage

(Lado and Wilson, 1994). This perspective explicitly suggests that the organizational set of

competencies should be renewed by the development of new competencies based on prior

assessment of existing competency set and the appropriate means of augmenting this set. The

renewal involves the need to discover and develop new competencies of employees and teams

that are complementary to the firm technological and organizational competencies and

supplementary to those possessed in the past (Eisenhardt and Martin, 2000). Specific to

global virtual teams (i.e. GVTs) and their members, the value-creating competencies of

include the following:

The base skills and innate characteristics of GVT members

that are attributable to the individuals themselves (e.g. intellect, experience base,

education, emotional stability, etc.). These individual competencies also include not only

specific characteristics that make a GVT member more socially appealing for

collaboration to other members, but also skills that help in increasing the ability of a GVT

member to address complex problems and ill-structured problems. To address and solve

such problems, specific interpersonal skills that enable a GVT member to learn and share

knowledge, as well as to gain recognition and influence over others are critical (Lado and

Wilson, 1994).

Self-related competencies

Team context-related competencies The ability and skills of GVT to exhibit the capacity

for cognitive and social differentiation and integration of task-relevant variables in the

context of innovation in the organization (i.e. including specific knowledge and human

capital of GVT members to build informal (cross) cultural networks that result in

social/cultural capital, as well as political skill to promote a culture of trust and to suppress

conflict in accomplishing the task of the GVT). These contextual competencies of GVTs are

particularly valuable to provide institutional bridges across the cultural, social, and political

divide between the headquarters and foreign subsidiaries that is associated with various

knowledge management initiatives in the firm (Novicevic and Harvey, 2001). Such

competencies may reshape the thinking and actions about globally distributed knowledge

1586 The International Journal of Human Resource Management

management initiatives to influence the worldview of the top management of the global

organization, providing it ultimately with a global mindset (Kafelas, 1998; Poole, 1998).

Vision-related competencies The GVT competencies to transform symbolically the

vision of its goals into the reality of its actions, which underscore collective adaptability

and learning capacity of GVT members to envision new commons for organizational

members and other stakeholders (Bluedorn, 2002; Harvey et al., 1999).

These

transformational competencies reflect the capacity of GVT to develop a vision of

innovations and shape the decisions and actions necessary to blend the patience of the

collaboration with the passion of realizing that vision (Lado et al., 1992). Such a broad

set of competencies may also include the capacity to engage in alliance-based

innovations that facilitate new product and customer relationship development (Lado

et al., 1992). Similarly, these competencies also include the capacity to create a learning

experience and/or support for customers by enacting a context of collaborative culture

conducive to learning and sharing knowledge. As such culture is socially complex it is

difficult for competitors to replicate and therefore can be the source to create a relative

competitive advantage over global rivals (Roth and ODonnell, 1996; Taylor et al.,

1996).

These three types of distinct competencies should be bundled in order to be valuable

for organizations fostering global virtual teamwork and innovations in todays

hypercompetitive global markets (DAveni, 1994, 1997, 1999). Given the increase in

intense rivalries among firms that is based on integrating globally distributed innovation

through teamwork, it is necessary to explore if HR architecture may positively influence

this competency set of GVTs and GVT members (i.e. self, contextual and vision-related)

and contribute to an organizations dynamic capabilities in innovative undertakings

(Desouza and Evaristo, 2003; Peterson and Cheng, 1998; Zander and Kogut, 1995).

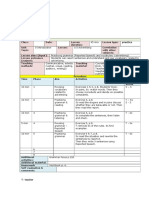

Figure 1 illustrates how HR architecture may facilitate timely transfer and sharing of

knowledge to increase the global organizations dynamic capabilities to compete

effectively against the increasing complexity of global competitors.

The architectural conceptualization of HR capital for GVTs is a useful vehicle in the

analysis of how the management of corporate HR architecture can add value in balancing

two competing demands: (1) the development of a firm knowledge base; and (2) the

knowledge sharing by collaborating GVT members (see Figure 1).

Figure 1 HR systems and capital architecture in global virtual teams

Harvey et al.: Global virtual teams 1587

Human capital viewed in the context of GVT competency

The essence of competitive advantage emanating from the unique bundling of human

resources embedded in GVTs rests on the global organizations investments in human

capital through the training and development of globally competent managers and teams.

As GVTs add value to the global organization, the skills and knowledge captured in the

GVTs enhance productivity (Snell and Dean, 1992). As more organizations evolve into a

global strategic orientation and expand into emerging markets, the integration and

sharing of knowledge about under-served emerging markets (Garten, 1997) become

essential (Harvey and Buckley, 1997). The success of a global organization will be

predicated on its ability to develop efficient GVT capital across the network of

relationships that is strategically aligned and at the same time, may develop independent

effective initiatives for local competitive positioning via GVTs (e.g. thinking globally

and acting locally) (Amin and Cohendet, 1999; Kefalas, 1998; Woolcock, 1998).

It is important to recognize that the radical change in the competitive environment

from developed to emerging markets may necessitate a re-examination of the profile of

talent to be used on GVTs. As has been documented by strategy researchers, a radical

change in environment may require more appropriate competencies of team members

collaborating in the new environment (Guthrie et al., 1991; Pfeffer and Salanick, 1978).

The renewed interest in measuring the value/quality of human capital and its impact on

organizational performance that has occurred over the last several years (Beatty et al.,

forthcoming; Becker and Huselid, 1999; Huselid and Barnes, 2002) highlights these

issues. The intent of these and other studies is to cast HRM into a strategic rather than a

tactical role in the competitive posture of global organizations. These authors identify the

characteristics of an environment where human capital measurement systems (HCMSs)

are of most importance, they are: (1) uncertain and rapidly changing environments; (2)

knowledge intense industries; (3) when human capital is used to differentiate the

organization from the competition (i.e. unique intangible resource); (4) complex

product/service offerings; (5) divisionalized or network organization structure; (6)

lengthy time to introduce new products; and (7) where competent human capital is

depleted (Huselid and Barnes, 2002). It should be noted that these environments often

require the use of GVTs.

In addition to explicitly measuring the value of human capital it is significant to note that

the perceived value or importance of human capital can vary between employees and

management (see Figure 2). The perspective on augmenting human capital is consistent in

the upper left-side box and the lower right-side of the matrix. The disagreements over the

enhancement or reduction in human capital occur in the two other cells in the matrix.

Management expectations can augment human capital by expanding the pool of GVT

candidates and by limiting the membership from any one pool of employees. While at the

same time, the employees want to gain/maintain their level of importance and value to

the organization by remaining critical to the success of the organization. Human capital has

become so important for the dynamic capabilities of global organizations that HR managers

need to develop dynamic means to measure the value of their organizations human capital.

Recent findings suggest one specific approach to measuring the implicit impact of human

capital that is divided into six steps. HR managers must first focus on the impact and/or

productive results of human capital rather than the process oriented cost perspective of

managing the HR process. Second, they must develop an awareness of human capital

alchemy or recognizing that measuring historic measures of the value of human

capital are somewhat flawed in that they focus attention on the input nature rather than the

output impact of human resources. Third, both the human capital value and relationships

1588 The International Journal of Human Resource Management

Figure 2 GVT and employee perceptions of human capital development

(i.e. recognizing the impact of human capital on the drivers of an organizations financial

performance) need to be explored to insure that measures illustrate the value of human

capital on business results. Fourth, to recognize the limitations of using historic

benchmarking methods to determine the value of human capital, in that human capital has a

unique impact on results based upon the firms strategy and the influence of the blend of

human capital on results. Fifth, assessing the value of human capital should not start with the

measures themselves but rather measuring the contribution of the human capital in

accomplishing the strategy of the organization. Sixth, metrics of human capital should be

placed in an overarching human capital architecture or examining the impact in a systemic

manner rather than looking at human capital as an entity in and of itself (Becker and Huselid,

1999).

In sum, human capital is no longer a simple task of counting the number of

employees and their backgrounds. Rather, human capital has become both a strategic tool

of management that can directly influence dynamic capabilities of the global

organization as human capital can play a significant role in the superior performance

of the organization (Becker et al., 2001; Hitt et al., 2001; Huselid, 1995).

Social capital viewed in the context of GVT competency

Social capital is defined as an asset that is engendered via social relations that can be

employed to facilitate action and achieve above-normal rents (Adler and Kwon, 2002;

Baker, 1990; Hunt, 2000; Hunt and Morgan, 1995; Leana and Van Buren, 1999). In a global

management context, social capital has been primarily conceptualized as a resource

reflecting the character of social relations within a firm (Hunt, 2000; Kostava and Roth,

2003) that extends beyond firm boundaries providing a basis for inter-firm action.

Although the term social capital has received considerable attention in the literature,

consensus on its theoretical domain and tenets have yet to be achieved (Leana and Van

Buren, 1999). In a review of the social capital literature, Leana and Van Buren (1999)

note that the literature presents a variety of perspectives on the levels of analysis

and the dimensions of this concept. They further indicate that two productive

underlying dimensions are common to existing conceptualizations of social

capital: associability and trust.

Associability is defined as the willingness and ability of participants to subordinate

individual level goals and associated actions to collective goals and actions (Leana and Van

Buren, 1999). The inherent subornation of individual goals through participation in the

collective however is not a relinquishment of individual goals, but rather an active mechanism

Harvey et al.: Global virtual teams 1589

that individuals employ to pursue individual goals (Leana and Van Buren, 1999). Through

participation in efforts to meet group objectives, the individual is able to achieve his/her

individual goals. This is not to imply a self-serving purpose, but rather through identification

with the group the individual works toward the group objective, and residually toward his/her

own goals (Leana and Van Buren, 1999). Given the nature of associability, it has both affective

(i.e. collectivist feelings) and skill-based components (e.g. ability to co-ordinate activities).

A second component of social capital is trust. Trust is evident when one has

confidence in anothers reliability and integrity (Das and Teng, 1998; Leana and Van

Buren, 1999; Morgan and Hunt, 1994). It has been asserted that co-operative, long-term

relationships are dependent upon the fostering of trust (Das and Teng, 1998; Morgan and

Hunt, 1994). Researchers have proposed that trust can be considered in terms of a risk

reward relationship (Mayer, 1995; Williamson, 1993), where predictable actions by one

party allow the relationship to operate more effectively. The value of trust is derived

from a reduction in risk of opportunistic behaviour on the part of ones exchange partner

thus reducing the costs of the relationship (Williamson, 1993). Further, when someone is

trusted, others are more willing to commit (Das and Teng, 1998; Leana and Van Buren,

1999; Morgan and Hunt, 1994). Through the development of trust in the relationship,

repetitive transaction sequences occur, thereby reducing transaction costs.

Trust extends beyond dyadic relations via generalization through affiliation and reputation

(Leana and Van Buren, 1999). Putnam (1993) argues that trust can reside at the generalized

level via the development and adherence to generally accepted norms and behaviours. Thus,

an individual or firm that adheres to the generally accepted norms and behaviours embedded

within set social relations can be trusted even though a member joining the firms associations

does not have personal knowledge of, or interaction with, the firm.

The dimensions of associability and trust are both attributes of the group as well as

the individual. Therefore, social capital can be conceptualized as an attribute of a

collective, as well as the sum of the individual relations. Leana and Van Buren (1999)

argue that acts that enhance individual social capital benefit the collective directly and

the individual indirectly, thus tying individual level social capital to team and firm level

capital.

Political capital viewed in the context of GVT competency

The concept of political capital relates to the capacity of GVT members to develop

political skill during their global assignments. The dimensions of political capital

include: (1) reputational capital (i.e. the GVT members that are known in the global

network as having the political skill for getting things done expediently); and

(2) representative capital (i.e. reflecting the constituent support and/or legitimacy the

GVT members may be granted for discretionary initiatives) (Lopez, 2002). Political

capital is not the same as the social grease attributed to social capital but is a capacity

that rests among some GVT members to exhibit leadership in removing co-operative

barriers and build political goodwill by creating a shared team-first mentality.

The six leadership behaviours of GVT members that can influence the formation of

political capital are:

. social approximation: the degree of interaction synchronicity between the leader and

those in the GVT and the organization with whom the leader has developed political

capital;

. level/type of interaction: access to the leader and the type of interaction (i.e. face-toface, electronic or other) between the leader and GVT members;

1590 The International Journal of Human Resource Management

. scope and reach: the breadth of the network of members who perceive the leader as

having political capital;

. dispersion of knowledge: the knowledge level within the leaders political network;

. durability: the leaders lasting or residual capacity of political capital; and

. degree of formality: the degree to which the leaders political capital is legitimized in

the GVT and in the organization via position or formal authority.

Therefore, it is important to recognize these individual behaviours when attempting to

formalize development programmes for global leaders and augment political capital at

the firm level.

Political capital of GVT members, accumulated in global relationships internally as

well as externally to the organization, can reduce the level of conflict and dysfunctional

consequences between the GVT and its interacting parties/entities within the global

environment. With an adequate level of political capital, others (i.e. peers, subordinates,

and even superiors) in the global network organization will tend to acquiesce to the

GVT leader who has demonstrated political skill (i.e. established bankable political

capital). Once political capital has been established for the GVT leader, it reflects his/her

reputation to represent diverse interests within the global organization.

However, given the lack of portability of some social capital and social networks

across national borders and organizational boundaries, GVT members political and

social ties may be of limited across some settings (Burt, 1992; Brass, 1995; Coleman,

1998). The composite effect of an alien setting and the temporary nature of GVTs

interactions can dramatically reduce the teams self-efficacy and the ability of the GVT

leader to effectively leverage his/her reputation (Bandura, 1982, 1995; Litt, 1988,

Wooldridge and Maddox, 1995). Therefore, organizational settings can reduce the

political effectiveness of the GVT leader, particularly in the short term (Ogbonna and

Harris, 2000; Reichers and Schneider, 1990; Schein, 1996).

In many settings, GVTs have to operate at the interface between two organizational

levels (i.e. headquarters and regional centres) (Florin, 1997; Gomes-Casseres, 1996;

Lorange and Roos, 1992). Thus, the political skill and capital of GVTs need to be attuned

to both the organizations levels and their distinct knowledge management initiatives

(Parkhe, 1993; Sagrero and Schrader, 1998). The internal cultures at the two levels may

sometimes be dramatically different, thus increasing the complexity of the political skill

set needed in the GVT. In addition, given the limited time to build social capital at these

two levels, GVTs often need to rely on the political skill or capital of their leaders to

effectively reach their goals. Otherwise, the absence of trust between the GVT members

and other managers in the network of organizations reduces the teams capabilities and

the overall effectiveness of the GVT (Aulakh et al., 1997; Inkpen and Currall, 1997;

Sarkar et al., 1997).

Another issue that must be taken into consideration when assessing/developing the

political capital of GVT members is the limitation on the teams decision-making

discretion in settings of foreign joint venture organizations. Moreover, when overseas

operations are jointly owned by a number of organizations (i.e. strategic alliances) from

different countries and, therefore, the limit of a GVT and its leader to exercise control

and/or influence is shaped by the relative ownership positions of the participants (Florin,

1997; Casmir, 1999). Because these confederations of organizations typically have very

complex operating cultures, they require specific political agility that can be exhibited by

few GVTs and their leaders (Harvey and Lusch, 1995). Therefore, the GVT leaders

political skill is critical in a shared ownership position of the various foreign

organizations (Hamel, 1991).

Harvey et al.: Global virtual teams 1591

Cross-cultural capital viewed in the context of GVT competency

Recently, there has been renewed interest in cross-cultural research in organizations

with respect to the impact of individual managers and team members on how to

effectively manage in a cross-cultural manner (Early and Ang, 2002; Earley and

Gibson, 2001; Earley and Mosakowski, 2000; Earley and Singh, 2000). The

key concept coming from this stream of research is cultural intelligence of individuals

(i.e. individual capability to adapt effectively to new cultural context and/or to be

able to effectively bridge issues and activities between two cultures) (Early and

Ang, 2002). Cross-cultural intelligence can influence the cultural capital of GVT

members in terms of the teams ability to implement knowledge initiatives in the global

marketplace.

Envisioning cross-cultural competence, Earley and Ang (2002) have identified three

interrelated facets of cultural intelligence, which are relevant for GVT members:

. cognitive dimension: self-awareness, external scanning, inductive reasoning and the

resulting cultural strategy developed by the individual;

. motivational dimension: self-efficacy, persistence, enhancement of self and/or face

and values; and

. behavioural dimension: repertoire (i.e. past cross-cultural experiences), practice or

level of interaction cross-culturally, habits (i.e. culturally related reading, study,

and knowledge development), and mimicry of varying observable cultural

habits/nuisances.

Applying these facets or dimensions to cross-cultural intelligence, one can identify the

key resources needed by GVT members to build cross-cultural capital. This competence

is of importance because of the very nature of the GVTs on-going function, that being

interfacing and building cultural bridges between the global organization and its

internal and external constituents. The accumulated (cross) cultural capital allows

the GVT members to gather and interpret information and to enact response to the

multitude of cultures in which the team may interact. This cultural capital becomes an

important stock when the leaders of the GVT are attempting to have a strategic impact

on entities in the foreign country and the team must adapt to the cultural nuisances of

the local country (Kayworth and Leidner, 2002; Pauleen, 2003). While cross-cultural

capital may have a common foundation, the GVT members must develop and maintain

cultural competence in each of the unique environments that the GVT faces during its

various assignments.

Cross-cultural capital emanates from the composite cultural intelligences of GVT

members and their ability to store the capital for future use by the team. The teams

ability to discern the typical patterns from the cultural settings in which the GVT may

operate and the GVT members experience in addressing later similar situations can be

construed as a quick measure of cultural intelligence in a GVT context. In addition, the

teams self-efficacy determines its willingness (i.e. motivation) to effectively engage

in new cultures and process the novelty found in each culture (Earley and Ang, 2002).

The inherent motivation to succeed and reach the GVT goals provides the impetus for

the formation of cross-cultural capital. The repertory breadth and past experience thus

serve as the cross-cultural skill of the GVT to adapt to individual cultural

settings (Earley and Gibson, 2001; Gibson et al., 2000). In general, cross-cultural

capital grows in importance as the global organization becomes more dependent on

GVTs to open new frontiers of knowledge management as the web of organizations

relationships expands.

1592 The International Journal of Human Resource Management

Assessment programme for HR capital architecture of GVTs

It becomes imperative that human resource managers recognize that GVTs are a unique

organizational configuration and to have them function effectively, various types of

capital must be generated and then built over time. The process for developing and

monitoring the successful development/maintenance capital in GVTs is outlined in this

section (see Figure 3).

Establishment of GVT capital assessment process

The initial stage in the assessment process for monitoring capital in GVT is to formalize the

process and to institutionalize it, so that it becomes a standard operating procedure (SOP).

This stage enables management to identify the basic infrastructure, resources and timetable

of the assessment process. The infrastructure entails detailing who is going to conduct the

process, when the process is going to be evaluated and a full delineation of the precise steps

to be taken in each stage of the assessment process.

The resources are the managers who will be involved as well as the cost of collecting

the information to make a clear assessment of the condition of capital in each GVT. It is

important to note that there will/could be a number of GVTs in a company that may have

different stocks of capital. The next step is to determine who is going to conduct the

assessment (to be discussed in more detail in stage two of the assessment process) and

what training/background the assessment group needs. Ideally, the assessment group

should match the importance/complexity/diversity of the types of GVTs. The last step in

this stage of the assessment process is to have a standardized set of milestones that are

Figure 3 Step-by-step GVT capital assessment

Harvey et al.: Global virtual teams 1593

agreed upon by the top management of the organization to report the information related

to the capital maintained in each GVT.

Establishment of monitoring assessment team

In this stage, the number of assessment group members is determined and the diversity

desired on the assessment group identified. The number of group members is contingent

to a degree on the number of GVTs that the company is using in its knowledge

management initiatives. The complexity of the assessment process is compounded by the

number and diversity of the GVTs. In addition, the functional expertise and experience in

the measurement of intangible assets, such as GVT capital, is ultimately a determining

factor in the size of the assessment team. Therefore, it is envisioned that the group

assessing the GVT capital will have to incorporate at times more ad hoc members to

augment professional skills needed in the assessment group.

The issue of additional skills needed in the assessment group should be addressed once

the demands for the level of expertise and experience are determined. However, it is

imperative to have a diverse set of auditing skills represented on the assessment group.

The domains of specific expertise would include: accounting, logistics and legal areas.

In sum, the skill set and experience should be the driving factors in the selection of the

assessment team members.

Establishing of effective monitoring metrics for GVT capital

Developing an appropriate set of measurements for monitoring GVT capital will require

extensive knowledge of the GVT and the assessment of intangible assets. The metrics should

be based upon the following principles relative to the capital within each GVT: (1) imitability

(i.e. the difficulty of competitors to duplicate the capital of an organizations GVT) increases

the sustainability of the income stream gained from the capital; (2) durability, the expected

resource life of the capital, its length of usefulness to the GVT; (3) appropriability, the flow of

value from the capital held in the GVT; (4) substitutability, uniqueness of the capital to sustain

value with key global stakeholders; and (5) superiority, relative value of the capital source

among other assets of the GVT (Collins and Montgomery, 1995; Harvey and Lusch, 1995).

There are two primary dimensions of GVT capital measurement. First is the value

assignment aspect, which reflects the need to assign value to GVT capitals and their

potential impact/benefits on the performance of the GVT. Second would be to determine

what causes value of the capital and how much value is derived from each of the capitals

contained in the GVT. Given these two considerations it is possible to start developing

the specific metrics for each type of GVT capital.

There appears to be no shortage of metrics to be used to measure knowledge and/or

intellectual capital that could be converted to be used in the measurement of GVT

capital (Barsky and Marchant, 2000; Bontis et al., 1999; Boudreau, 1991, 1996, 2002;

Low and Seisfeld, 1998; Roos and Von Krogh, 1996). Two metrics that appear to be

adaptable to measuring the GVT capital stocks are: (1) economics value added (EVA)

can provide a fundamental GTV performance measure which is computed by the spread

between the return on capital and the cost of capital, and multiplying by the capital

outstanding (i.e. the value of the capital the pervious year) at the beginning of the year;

and (2) market value added (MVA), the difference between a GTV market value of

capital and the capital that was contained in the GVT when operationalized. MVA is the

measure of the value that the GVT has created in excess of the tangible resources already

committed to the team (Stewart, 1997a, 1997b). If the MVA is positive, it suggests that

superior returns on existing GVT capital are being earned (Harvey and Lusch, 1997).

1594 The International Journal of Human Resource Management

Developing contingency strategies for protecting GVT capital

If not formally attended to by the GVT, the capital stock of the team can be depleted.

Therefore, a capital security programme/plan must be instituted to project the intangible

core of capital in the GVT. It is easy to ignore the security of this fragile intangible

capital because: (1) traditional lack of attention by corporate control/auditing personnel

(i.e. lacks GAAP accounting value); (2) historic difficulty in establishing monetary value

of intangible assets like GVT capital; (3) frequently, a lack of formal monitoring/control

mechanism in GVT teams or foreign subsidiaries, for that matter, to account for

intangible assets; (4) intangible assets such as GVT capital are not germane to

management appraisal and compensation; and (5) when capital is depleted or lost there is

no immediate economic impact (i.e. loss of capital impacts the GVT over time due to

lack of team effectiveness) (Harvey and Lusch, 1997).

There are four elements in developing a security programme to protect capital stocks

in GVT. First, identification of the various capital stocks (levels) and their importance to

the GVT accomplishing its goals/strategies. Second, the location (i.e. which team

members possess the capital that is accumulated into the team level) of the capital in the

team. Third, a security posture for the GVT team needs to be developed, that being either

proactive or reactive to attacks (or potential attacks) on the capital of the team. Fourth, an

assessment is to be performed relative to the previous attempts to protect capital stocks

from various threats. The protection of GVT capital will need to be a co-ordinated effort

using multiple prevention means.

Strategic development of means to build/maintain GVT capital

Protection of GVT capital provides the team with a means to account for existing capital

but does not address the means to build the various capitals in the GVT. Proactive

strategies for developing the stock of GVT will need to be developed. Each of the

strategies will need to be fashioned to the particular capital stock and the capabilities of

the members of the GVT. Given the constraints of this research effort it is not possible to

develop the logic for the building of GVT capital but team members should be made

aware of the need for not only monitoring but also building GVT capital.

Monitoring and auditing GVT capital over time

The final step in the capital assessment process is to institutionalize the need for monitoring

and accounting for the various capitals contained in the GVT. This removes the tendency for

management of the GVT to take its capital stocks for granted. In addition, capital is

transformed into a team asset and not just a human resource characteristic. This distinction is

very important in that managers come and go (i.e. ergo attributed capital to individual

managers who be mobile and attributed to the manager) but the GVT must maintain a

reservoir of capital within the GVT. Therefore, parallel sources of critical capital must be

identified and/or built to maintain the capabilities and competencies of the team as a whole.

In addition, the bundling of resources into complexes of related capital should also be

undertaken to elevate the capital to a team resource and help improve the performance of the

GVT.

Conclusion

As the global environment becomes more hyper-competitive, many organizations will

have to develop teamwork-grounded business models in order to address the new

competitive landscape (Bettis and Hitt, 1995). Such performance landscape, replete in

Harvey et al.: Global virtual teams 1595

disruptive technological advancements, has lead to the rise of innovation-based

competition. The complexity and dynamism of the new economy means organizations

need innovative ways to cultivate and manage human and technological resources.

In particular, the growing importance of global virtual teamwork illuminates the need for

the assessment of the HR capital architecture within the organization to allow the firm to

renew and reconfigure its core competencies within the competitive flux of the global

arena. In order to stay innovative and ahead of competition, global organizations must

pursue a strategic vision addressing the dynamic and complex issues of global virtual

teamwork by tapping those HR capital bases that are vital in maintaining or creating a

competitive heterogeneity.

Global organizations increasingly pursue the implementation of GVTs as a strategic

tool in the hyper-competitive environment, since these teams have the potential to

increase the speed and efficiency in the creation and transfer of knowledge in various

knowledge management initiatives pursued by the headquarters and regional centres of a

global organization (Kogut and Zander, 1996). The contribution of a GVT to the

relationship between organizational knowledge and its competitive advantage lies in its

ability to integrate knowledge in a productive manner (Nahapiet and Ghoshal, 1998).

Ultimately, the success of a global organization will be predicated on its ability to

develop rich HR capital bases across the network of its GVTs and their members.

The design of HR capital architecture is needed to expedite the stock and flow of

knowledge as a resource, in a manner that is conducive to relating the effectiveness of to

the intellectual capital base of the firm. Such HR capital architecture should enable GVTs

to function as knowledge agents allowing the global organization to renew and

reconfigure its dynamic capabilities, while enriching its overall intellectual capital base.

In terms of the role of GVTs within the relationship between the HR capital architecture

and the intellectual capital of the firm, it is critical to maintain and enhance the

heterogeneity of human, social, political and cross-cultural capital components through a

continuous assessment and reassessment programme.

References

Adler, P. and Kwon, S. (2002) Social Capital: Prospects for a New Concept, Academy of

Management Review, 27(1): 17 40.

Amin, A. and Cohendet, P. (1999) Learning and Adaptation in Decentralized Business Networks,

Environment and Planning, 17(1): 87 104.

Aulakh, P., Kotabe, M. and Sahay, A. (1997) Trust and Performance in Cross Border Marketing

Partnerships: A Behavioral Approach, Journal of International Business Studies, 27(5): 100532.

Baker, W. (1990) Market Networks and Corporate Behavior, American Journal of Sociology, 96:

589 625.

Bal, J. and Foster, P. (2000) Managing the Virtual Team and Controlling Effectiveness, International

Journal of Production Research, 38(17): 401932.

Bandura, A. (1982) Self-Efficacy Mechanism in Human Agency, American Psychologist, 37:

122 47.

Bandura, A. (1995) Comments on the Crusade Against the Causal Efficacy of Human Thought,

Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 26: 17990.

Barsky, N.P. and Marchant, G. (2000) The Most Valuable Resource measuring and Managing

Intellectual Capital, Strategic Finance, 81: 58 62.

Beatty, R., Huselid, M. and Schneier, C. (forthcoming) The New HR Metrics: Scoring on the

Business Scorecard, Organizational Dynamics.

Becker, B.E. and Huselid, M.A. (1999) Strategic Human Resource Management in Five Leading

Firms, Human Resource Management, 38: 287 301.

1596 The International Journal of Human Resource Management

Becker, B., Huselid, M. and Ulrich, D. (2001) The HR Scorecard: Linking People. Strategy and

Performance. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

Bettis, R. and Hitt, M. (1995) The New Competitive Landscape, Strategic Management Journal,

16: 7 19.

Bluedorn, A. (2002) The Human Organization of Time: Temporal Realities and Experience.

Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Bontis, N., Dragonetti, N.C., Jacobsen, K. and Roos, G. (1999) The knowledge toolbox: A review

of the tools available to measure and manage intangible resources, European Management

Journal, 17(4): 391 403.

Boudreau, J.W. (1991) Utility Analysis for Decisions in Human Resource Management. In

Dunnette, M.D. and Hough, L.M. (eds) Handbook of Industrial and Organizational Psychology,

(2nd ed.) Vol. 2. Palo Alto: Consulting Psychologists Press, pp. 621 745.

Boudreau, J.W. (1996) The Motivational Impact of Utility Analysis and HR Measurement,

Journal of Human Resource Costing and Accounting, 1(2): 7384.

Boudreau, J.W. (2002) Strategic Knowledge Measurement and Management. Working Paper 02

17, CAHRS, Cornell University.

Brass, D. (1995) A Social Network Perspective on Human Resources Management. In Ferris, G.

(ed.) Research in Personnel and Human Resources Management, 13: 39 79. Greenwich, CT:

JAI Press.

Burt, R. (1992) Structural Holes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Casmir, F. (1999) Foundations for the Study of Intercultural Communication Based on a Third

Culture Building Model, International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 23: 91 116.

Coleman, J. (1998) Social Capital in the Creation of Human Capital, American Journal of

Sociology, 94: S95 S120.

Collins, D. and Montgomery, C. (1995) Competing on Resources: Strategy in the 1900s, Harvard

Business Review, 73(4): 119 28.

Daft, R.L. and Lengel, R.H. (1986) Organizational Information Requirements, Media Richness

and Structural Design, Management Science, 32(5): 554 71.

Das, T. and Teng, B.-S. (1998) Resource and Risk Management in the Strategic Alliance Making

Process, Journal of Management, 24: 21 42.

DAveni, R. (1994) Hypercompetition: Managing the Dynamics of Strategic Maneuvering. New

York: Free Press.

DAveni, R. (1997) Waking up to the New Era of Hypercompetition, The Washington Quarterly,

21(1): 18395.

DAveni, R. (1999) Strategic Supermacy through Disruption and Dominance, Sloan Management

Review, 40(3): 127 36.

Desouza, K.C. and Evaristo, J.R. (2003) Global Knowledge Management Strategies, European

Management Journal, 21(1): 62 7.

Earley, P.C. and Ang, S. (2002) Cultural Intelligence: An Analysis of Individual Interactions

Across Cultures. Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press.

Early, P.C. and Gibson, C. (2001) Multinational Work Teams: A New Perspective. New Jersey:

Erlbaum Associates.

Earley, C. and Mosakowski, E. (2000) Creating Hybrid Team Cultures: An Empirical Test of

Transnational Team Functioning, Academy of Management Journal, 43(1): 26 49.

Earley, P.C. and Singh, H. (eds) (2000) Innovations in International and Cross-Cultural

Management. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Eisenhardt, K. and Martin, J. (2000) Dynamic Capabilities: What are They?, Strategic

Management Journal, 21: 1105 21.

Finholt, T. and Sproull, L. (1990) Electronic Teams at Work, Organization Science, 1: 41 64.

Florin, J. (1997) Cooperate to Learn and Compete: An Integrative Framework of Inter-Firm

Learning, Trust, and Value. Paper presented at the Academy of Management Conference,

Boston, MA.

Garten, J. (1997) The Big Ten: The Emerging Markets and How They Will Change Our Lives.

New York: Basic Books.

Harvey et al.: Global virtual teams 1597

Gibson, C.B., Randel, A. and Earley, P.C. (2000) Work Team Efficacy: An Assessment of Group

Confidence Estimation Methods, Group and Organization Management, 25: 67 97.

Gomes-Casseres, B. (1996) The Alliance Revolution: The New Shape of Business Rivalry.

Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Guthrie, J., Grimm, C. and Smith, K. (1991) Environmental Change and the Top Management

Teams, Journal of Management, 17(4): 735 48.

Hamel, G. (1991) Competition for Competence and Inter-Partner Learning Within International

Strategic Alliances, Strategic Management Journal, 12: 83 103.

Harvey, M. and Buckley, M. (1997) Managing Inpatriates: Building a Global Core Competency,

Journal of World Business, 32(1): 35 52.

Harvey, M. and Lusch, R. (1995) A Systematic Assessment of Potential International Strategic

Alliance Partners, International Business Review, 4(2): 195 212.

Harvey, M., Speier, C. and Novicevic, M. (1999) Inpatriate Managers: How to Increase Probability

of Their Success, Human Resource Management Review, 9(1): 7990.

Hatch, M. (1997) Jazzing Up the Theory of Organizational Improvisation. In Walsh, J.P. and

Huff, A.S. (eds) Advances in Strategic Management, 14: pp. 181 91. Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.

Henry, J. and Hartzler, M. (1998) Tools for Virtual Teams: A Team Fitness Companion.

Milwaukee, WI: ASQ Quality.

Hitt, M., Bierman, L., Shimizu, K. and Kochhar, R. (2001) Direct and Moderating Effects of

Human Capital on Strategy and Performance in Professional Service Firms: A Resource-Based

Perspective, Academy of Management Journal, 44: 13 28.

Hunt, S. (2000) The Competence-Based, Resource-Advantage, and Neoclassical Theories of

Competition: Toward a Synthesis. In Sanchez, R. and Heene, A. (eds) Theory Development for

Competence-Based Management. 6(A) in Advances in Applied Business Strategy series.

Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.

Hunt, S. and Morgan, R. (1995) The Comparative Advantage Theory of Competition, Journal of

Marketing, 59: 1 15.

Huselid, M. (1995) The Impact of Human Resource Management Practices on Turnover,

Productivity, and Corporate Financial Performance, Academy of Management Journal, 38:

635 72.

Huselid, M. and Barnes, J. (2002) Human Capital Measurement Systems as a Source of

Competitive Advantage. Manuscript in preparation for the Academy of Management Review.

Inkpen, A. and Currall, S. (1997) International Joint Venture Trust: An Empirical Examination in

Cooperative Strategies. In Beamish, P.W. and Killing, J.P. (eds) Vol. 1. North American

Perspectives. San Francisco, CA: New Lexington Press.

Jarvenpaa, S., Knoll, K. and Leidner, D. (1998) Is Anybody Out There? Antecedents of Trust in

Global Virtual Teams, Journal of Management Information Systems, 14(4): 29 64.

Kayworth, T. and Leidner, D. (2002) Leadership Effectiveness in Global Virtual Teams, Journal

of Management Information Systems, 18(3): 7 40.

Kefalas, A. (1998) Think Globally, Act Locally, Thunderbird International Business Review,

40(6): 547 62.

Kogut, B. and Zander, U. (1996) What Firms Do? Coordination, Identity, and Learning,

Organization Science, 7(5): 502 18.

Kostova, T. and Roth, T. (2003) Social Capital in Multinational Corporations and a Micro Macro

Model of its Formation, Academy of Management Review, 28(2): 97 103.

Lado, A. and Wilson, M. (1994) Human Resource Systems and Sustained Competitive Advantage:

A Competency-Based Perspective, Academy of Management Review, 19: 699 727.

Lado, A., Boyd, N. and Wright, P. (1992) A Competency-Based Model of Sustainable Competitive

Advantage: Toward a Central Integration, Journal of Management, 18(1): 77 91.

Leana, C. and Van Buren, III, H. (1999) Organizational Social Capital and Employment Practices,

Academy of Management Review, 24: 538 55.

Lei, D., Hitt, M.A. and Bettis, R. (1996) Dynamic Core Competences Through Meta-Learning and

Strategic Context, Journal of Management, 22(4): 549 69.

1598 The International Journal of Human Resource Management

Lepak, D. and Snell, S. (2002) Examining the Human Resource Architecture: The Relationships

Among Human Capital, Employment, and Human Resource Configurations, Journal of

Management, 24(4): 517 43.

Litt, M. (1988) Self-Efficacy and Perceived Control: Cognitive Mediators of Pain Tolerance,

Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54(1): 149 60.

Lopez, E. (2002) The Legislator as Political Entrepreneur: Investment in Political Capital, Review

of Austrian Economics, 15(2 3): 211 28.

Lorange, P. and Roos, J. (1992) Strategic Alliances: Formation, Implementation and Evolution.

Cambridge: Blackwell Publishers.

Low, J. and Siesfeld, T. (1998) Measures that Matter, Strategy and Leadership, 26(2): 24 9.

Mayer, R., Davis, J. and Schoorman, F. (1995) An Integrative Model of Organizational Trust,

Academy of Managerial Review, 20: 709 34.

Morgan, R. and Hunt, S. (1994) The Commitment-Trust Theory of Relationship Marketing,

Journal of Marketing, 58: 20 38.

Nahapiet, J. and Ghoshal, S. (1998) Social Capital, Intellectual Capital, and the Organization

Advantage, Academy of Management Review, 23: 242 66.

Nemiro, J.E. (2001) Connection in Creative Virtual Teams, Journal of Behavioral and Applied

Management, (Winter/Spring) 3(2): 92 112.

Novicevic, M. and Harvey, M. (2001) The Changing Role of the Corporate HR Function in Global

Organizations of the Twenty-first Century, International Journal of Human Resource

Management, 12(8): 279 92.

Ogbonna, E. and Harris, L. (2000) Leadership Style, Organizational Culture and Performance:

Empirical Evidence from UK Companies, International Journal of Human Resource

Management, 11(4): 766 88.

Oster, S. (1990) Modern Competitive Analysis. New York: Oxford University Press.

Pauleen, D. (2003) Leadership in a Global Virtual Team: An Action Learning Approach,

Leadership and Organization Development Journal, 24(3): 153 62.

Peterson, R. and Cheng, J.L.C. (eds) (1998) Advances in International Comparative Management,

Vol. 12. Stamford, CT: JAI Press.

Pfeffer, G. and Salanick, G. (1978) The External Control of Organizations. New York: Harper.

Poole, M. and Warner, M. (1998) The IEBM Handbook of Human Resource Management, 1st ed.

London. Boston: International Thomson Business Press.

Poppo, L. (1995) Influence Activities and Strategic Coordination: Two Distinctions of Internal and

External Markets, Management Science, 41: 1845 59.

Potter, R., Cooke, R. and Balthazard, P. (2000) Virtual Team Interaction: Assessment,

Consequences, and Management, Team Performance Management, 6(7/87): 131 7.

Putnam, R. (1993) The Prosperous Community: Social Capital and Public Life, American

Prospect, 13: 35 42.

Reichers, A. and Schneider, B. (1990) Climate and Culture: An Evolution of Constructs. In

Schneider, B. (ed.) Organizational Climate and Culture. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Roos, J. and von Krogh, G. (1996) The Epistemological Challenge: Managing Knowledge and

Intellectual Capital, European Management Journal, 14(4): 3337.

Roth, K. and ODonnell, S. (1996) Foreign Subsidiary Compensation Strategy: An Agency Theory

Perspective, Academy of Management Journal, 39(3): 678703.

Sarkar, M., Cavusigil, S. and Evirgen, C. (1997) A Commitment-Trust Mediated Framework of

International Collaborative Venture Performance. In Beamish, P.W. and Killing, J.P. (eds)

Cooperative Strategies. San Francisco, CA: The New Lexington Press.

Schein, E. (1996) The Three Cultures of Management: Implications for Organizational Learning,

Sloan Management Review, 38: 9 20.

Scott, S. and Einstein, W. (2001) Performance Appraisal in Ten-Based Organizations: One Size

Does Not Fit All, Academy of Management Executive, May, 15(2): 143 57.

Snell, S. and Dean, J. (1992) Integrated Manufacturing and Human Resources Management:

A Human Capital Perspective, Academy of Management Journal, 35: 467504.

Harvey et al.: Global virtual teams 1599

Stewart, T.A. (1997a) Intellectual Capital: The New Wealth of Organizations. London: Nicholas

Brealey.

Stewart, T.A. (1997b) The Wealth of Knowledge: Intellectual Capital and the Twenty-First Century

Organization. London: Nicholas Brealey.

Taylor, S., Beechler, S. and Napier, N. (1996) Toward an Integrative Model of Strategic

International Human Resource Management, Academy of Management Review, 21(4): 959 85.

Townsend, A., DeMarie, S. and Hendrickson, A. (1998) Virtual Teams: Technology and the

Workplace of the Future, Academy of Management Executive, 12(3): 17 29.

Townsend, A., DeMarie, S. and Hendrickson, A. (1996) Are You Ready for Virtual Teams?, HR

Magazine, 41(9): 122 6.

Williamson, O. (1993) Calculativeness, Trust and Economic Organization, Journal of Law and

Economics, 36: 453 86.

Woolcock, M. (1998) Social Capital and Economic Development: Toward a Theoretical Synthesis

and Policy Framework, Theory and Society, 27(2): 151 208.

Wooldridge, B. and Maddox, B. (1995) Demographic Changes and Diversity in Personnel:

Implications for Public Administrators. In Rabin, J. et al. (eds) Handbook of Public Personnel

Administration. New York: Marcel Dekker, Inc.

Zander, U. and Kogut, B. (1995) Knowledge and the Speed of the Transfer and Imitation of

Organizational Capabilities: An Empirical Test, Organization Science, 6: 76 92.

You might also like

- Cultural Misunderstandings Threaten US-China Business DealDocument17 pagesCultural Misunderstandings Threaten US-China Business DealOscarNo ratings yet

- BSG-PPT Class PresentationDocument29 pagesBSG-PPT Class PresentationPhuong LeNo ratings yet

- Global Virtual Teams, GVTsDocument7 pagesGlobal Virtual Teams, GVTsOscarNo ratings yet

- Global Virtual TeamsDocument4 pagesGlobal Virtual TeamsOscarNo ratings yet

- Exam 3 ManaDocument15 pagesExam 3 ManaOscarNo ratings yet

- Useful Equations For Physics 2Document10 pagesUseful Equations For Physics 2OscarNo ratings yet

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Classroom Talk - Making Talk More Effective in The Malaysian English ClassroomDocument51 pagesClassroom Talk - Making Talk More Effective in The Malaysian English Classroomdouble timeNo ratings yet

- Mariam Toma - Critique Popular Media AssignmentDocument5 pagesMariam Toma - Critique Popular Media AssignmentMariam AmgadNo ratings yet

- Analytical GrammarDocument28 pagesAnalytical GrammarJayaraj Kidao50% (2)

- Critical Reading ExercisesDocument23 pagesCritical Reading Exercisesztmmc100% (3)

- Nature of Human BeingsDocument12 pagesNature of Human BeingsAthirah Md YunusNo ratings yet

- Atg Worksheet Subjectobjpron PDFDocument2 pagesAtg Worksheet Subjectobjpron PDFАнна ВысторобецNo ratings yet

- TTT A1 SBDocument83 pagesTTT A1 SBsusom_iulia100% (1)

- Why Should I Hire YouDocument6 pagesWhy Should I Hire YouDebasis DuttaNo ratings yet

- Lesson 2 Correct Intonation For Statements and YN QuestionsDocument2 pagesLesson 2 Correct Intonation For Statements and YN QuestionsConnie Diaz CarmonaNo ratings yet

- 10.LearnEnglish Writing B1 Describing Charts PDFDocument5 pages10.LearnEnglish Writing B1 Describing Charts PDFوديع القباطيNo ratings yet

- Applied Linguistics Lecture 1Document18 pagesApplied Linguistics Lecture 1Dina BensretiNo ratings yet

- Etp 87 PDFDocument68 pagesEtp 87 PDFtonyNo ratings yet

- Art Appreciation 3Document7 pagesArt Appreciation 3Asher SarcenoNo ratings yet

- 1-II Mathematical Languages and Symbols (2 of 2)Document23 pages1-II Mathematical Languages and Symbols (2 of 2)KC Revillosa Balico100% (1)

- Lesson 4 With Review Powerpoint LANGUAGE ACQUISITIONDocument140 pagesLesson 4 With Review Powerpoint LANGUAGE ACQUISITIONGodwin Jerome ReyesNo ratings yet

- ThesisDocument39 pagesThesisJeanine CristobalNo ratings yet

- Task 6 Secular HumanismDocument4 pagesTask 6 Secular HumanismNoor Shiela Al BaserNo ratings yet

- Savickas Et Al 2009 - A Paradigm For Career Constructing in The 21st CenturyDocument12 pagesSavickas Et Al 2009 - A Paradigm For Career Constructing in The 21st CenturyPaulo Fonseca100% (2)

- Academic Paper2Document10 pagesAcademic Paper2api-375702257No ratings yet

- 7 Principles Constructivist EducationDocument2 pages7 Principles Constructivist EducationSalNua Salsabila100% (13)

- 5 Focus 4 Lesson PlanDocument2 pages5 Focus 4 Lesson PlanMarija TrninkovaNo ratings yet

- Why People Do BullyingDocument2 pagesWhy People Do BullyingSandra YuniarNo ratings yet

- Interactive WritingDocument6 pagesInteractive WritingNopiantie E. MartadinataNo ratings yet

- Elements of PoetryDocument18 pagesElements of PoetryJoan Manuel Soriano100% (1)

- ACL Arabic Diacritics Speech and Text FinalDocument9 pagesACL Arabic Diacritics Speech and Text FinalAsaaki UsNo ratings yet

- Overall SyllabusDocument525 pagesOverall SyllabusDIVYANSH GAUR (RA2011027010090)No ratings yet

- Dr. Ramon de Santos National High School learning activity explores modal verbs and nounsDocument3 pagesDr. Ramon de Santos National High School learning activity explores modal verbs and nounsMark Jhoriz VillafuerteNo ratings yet

- Science TechDocument121 pagesScience TechJulius CagampangNo ratings yet

- Lect 15 Coping Strategies With StressDocument31 pagesLect 15 Coping Strategies With Stressumibrahim100% (2)

- Elc Lira Bele-BeleDocument2 pagesElc Lira Bele-BeleNurulasyiqin Binti Abdul RahmanNo ratings yet