Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Alfa Bloqueo Anestesia RM

Uploaded by

Martin CanaleOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Alfa Bloqueo Anestesia RM

Uploaded by

Martin CanaleCopyright:

Available Formats

CORRESPONDENCE

The need for preoperative a-adrenergic blockade

for ganglioneuroma excision

SIRGanglioneuromas (GNs) are rare, benign, fully differentiated tumors that arise most commonly from the

sympathetic ganglia in the posterior mediastinum in

adolescents and young adults. The treatment involves

complete surgical excision and has an excellent prognosis. Compared with malignant neuroblastomas and

ganglioneuroblastomas, which frequently produce catecholamines, GNs secrete catecholamines only occasionally. The release of catecholamines during surgery,

which is one of the most feared complications, can be

catastrophic and difficult to manage. For this reason,

the British Paediatric Society of Endocrinology and Diabetes (BPSED) (1) and the panel of experts at the First

International Symposium on Pheochromocytoma (2)

have recommended that all patients with a biochemically positive pheochromocytoma should receive mandatory a-adrenergic blockade before any surgical

intervention. GNs are usually excised without such precaution, and there are no recommendations to suggest

the need for preoperative a-adrenergic blockade in these

cases. We report a unique case of ganglioneuroma excision that was unexpectedly complicated by the episodic

hypertensive spells upon tumor manipulation.

A 4-year-old boy presented with two-day history of

progressive ataxia to pediatric accident and emergency

three weeks after having chickenpox. At presentation,

he had broad-based gait with tendency to fall on right

side. His reflexes were slightly brisk in lower limbs. The

rest of neurological examination and blood pressure was

normal. His blood glucose, serum electrolytes, and full

blood picture were normal. The serum and urine toxicology screen was negative. Neurology opinion was sought,

and the ataxic gait was thought to be consistent with

cerebellitis. Chest X-ray showed a large lobulated posterior mediastinal mass projecting over right hemithorax

with pressure erosion of the right third rib. Computed

tomography (CT) of chest and abdomen showed a posterior mediastinal mass with numerous stippled features

in keeping with neurogenic tumor. Urinary catecholamines were requested, and thoracoscopic biopsy was performed to identify the tumor, which confirmed the

diagnosis of ganglioneuroma. There were no spikes in

blood pressure intraoperatively.

A week later, due to worsening ataxia and inability to

bear weight, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of chest

and spine was performed and revealed epidural extension of the tumor through wide intervertebral foramina

from the level of 1st thoracic/2nd thoracic intervertebral

2013 John Wiley & Sons Ltd

disc cranially to the level of 5th thoracic/6th thoracic

caudally with spinal cord compression. He then had

spinal laminectomy to relieve the cord compression.

During this surgery, he started having cyclical spikes of

blood pressure with systolic blood pressures ranging

from 50 to 200 mmHg. This was attempted to be controlled with glyceryl trinitrite infusion and phenylepherine boluses. Postoperatively, plasma normetanephrine

was noted to be increased at 3454 pmoll 1 (normal

range 1201180). Urine catecholamine/creatinine ratios

were increased for norepinephrine at 478 nmolmmol 1

creat (normal range 17194) and for dopamine at

1204 nmolmmol 1 creat (normal range 59901) with

urinary creatinine being 3.5 mM (normal range 7

18 mM). Testing for vanilylmandelic acid (VMA) and

homovanillic acid (HVA) is not available in this institution. A follow-up CT spine after 8 weeks showed small

residual intraspinal tumor with minimally increased thoracic component of the tumor that continued to displace

the mediastinal structures. MRI spine performed

6 months later showed no residual intraspinal soft tissue

component with minimally increased right paramediastinal mass. He then had further surgical excision, and this

time, it was performed with preoperative a-adrenergic

blockade using phenoxybenzamine as per BPSED pheochromocytoma guidelines. He stayed very stable during

the surgery with no hypertensive crises.

The literature regarding childhood GN is scarce, especially on such a relevant issue of surgical approach. A

retrospective study by the Italian Co-operative Neuroblastoma Group concerning a large number of patients

registered as GN over a 27-year period also did not

report any case of surgery complicated by hypertensive

crisis (3). Also, a literature search on the perioperative

management of neuroblastomas was also carried out

with inconclusive results and recommendations. A large

review of 20 years (4) experience showed <3% incidence

of intraoperative hypertension during neuroblastoma

resection and recommended only a-blocking those

patients with significant preoperative signs and symptoms of catecholamine excess. Another large review of

11 years (5) experience confirmed the same and did not

recommend any specific optimal anesthetic regimen. The

downside to routine recommendation of a-adrenergic

blockade for all neurogenic tumors is the subsequent

delay in surgery in newly diagnosed neuroblastomas and

the potential detrimental effect this can have on prognosis of the child.

1

Correspondence

In conclusion, this case highlights the need for the recognition of the fact that, like pheochromocytomas, safe

surgical excision of ganglioneuromas may require

appropriate a-adrenergic blockade and guidelines need

to devised for perioperative management in such

patients. Further studies are needed to compare preoperative urinary catecholamines quantitatively to surgical

complications as a result of catecholamine release which

might provide criteria for a-adrenergic blockade in specific patients. In the meantime, surgeons and anesthetists

need to be aware of this possible complication and be

prepared for hypertensive crises that can occur.

Conflict of interest

No conflict of interests declared.

Chandan Gupta, Noina Abid, Keith Bailie, Mark Terris,

Alistair Dick & Anthony McCarthy

Royal Belfast Hospital for Sick Children, Belfast, UK

Email: chandan_gupta60@yahoo.com

doi:10.1111/pan.12335

References

1 BSPED | British Society for

Paediatric Endocrinology and

Diabetes | Clinical [Internet]. Available

at: http://www.bsped.org.uk/clinical/

clinical_endorsedguidelines.html. Accessed

13, February 2013.

2 Pacak K, Eisenhofer G, Ahlman H et al.

Pheochromocytoma: recommendations for

clinical practice from the First International

Symposium. Nat Clin Pract Endocrinol Metab

2007; 3: 92102.

3 De Bernardi B, Gambini C, Haupt R et al.

Retrospective study of childhood ganglioneuroma. J Clin Oncol 2008; 26: 17101716.

4 Haberkern CM, Coles PG, Morray

JP et al. Intraoperative hypertension

during surgical excision of neuroblastoma.

Case report and review of 20 years

experience. Anesth Analg 1992; 75:

854858.

5 Kain ZN, Shamberger RS, Holzman RS.

Anesthetic management of children with

neuroblastoma. J Clin Anesth 1993; 5:

486491.

2013 John Wiley & Sons Ltd

You might also like

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Breast Unit SOP: Checklist While Giving ROIS AppointmentDocument7 pagesBreast Unit SOP: Checklist While Giving ROIS AppointmentAbhinav Ingle100% (1)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5795)

- Health Referral System Manual - Central VisayasDocument103 pagesHealth Referral System Manual - Central VisayasAlfred Russel Wallace50% (10)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- A Simple Technique To Measure The Volume of Removed Buccal FatDocument3 pagesA Simple Technique To Measure The Volume of Removed Buccal FatGuilherme GuerraNo ratings yet

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Updates in Ophthalmic Anaesthesia in AdultsDocument7 pagesUpdates in Ophthalmic Anaesthesia in AdultsJossiel OlivaresNo ratings yet

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Clinical Application of Nightingale TheoryDocument9 pagesClinical Application of Nightingale TheoryHina Nizar100% (2)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- To Evaluate The Efficacy of Ultrasonography Guided Pectoral Nerve Block For Postoperative Analgesia in Breast SurgeriesDocument4 pagesTo Evaluate The Efficacy of Ultrasonography Guided Pectoral Nerve Block For Postoperative Analgesia in Breast SurgeriesInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Batu Ren, Batu Ureter Dan Onko NewDocument29 pagesBatu Ren, Batu Ureter Dan Onko Newilham masdarNo ratings yet

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Revised Dentist (Code Od Ethics) Regulations, 2014 PDFDocument10 pagesThe Revised Dentist (Code Od Ethics) Regulations, 2014 PDFRohit AgrawalNo ratings yet

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- 279667.locs IiiDocument16 pages279667.locs IiiSiomay IkanNo ratings yet

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Tam MannaDocument2 pagesTam MannaYashwanth GowdaNo ratings yet

- Como Analizar Un ArticuloDocument4 pagesComo Analizar Un ArticuloAlvaro Alvarez RiveraNo ratings yet

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Career GuidanceDocument19 pagesCareer GuidanceAbdul JalilNo ratings yet

- General Surgery&plastic Surgery Board-Part One Exam Blueprint (v.1)Document4 pagesGeneral Surgery&plastic Surgery Board-Part One Exam Blueprint (v.1)Mohammed S. Al Ghamdi100% (1)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- 4.2 MDS01 - Definition Table of The MDS Items - Ver0.94Document7 pages4.2 MDS01 - Definition Table of The MDS Items - Ver0.94AriniDwiLestariNo ratings yet

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Operating Room ConceptsDocument47 pagesOperating Room ConceptsLoungayvan Batuyog100% (1)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

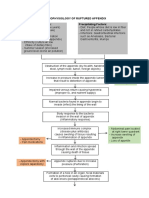

- Pathophysiology of Ruptured AppendixDocument2 pagesPathophysiology of Ruptured AppendixAya PaquitNo ratings yet

- Minor Surgical Procedures in Maxillofacial SurgeryDocument65 pagesMinor Surgical Procedures in Maxillofacial SurgerydrzibranNo ratings yet

- Hubungan Tindakan Perawatan Luka Dengan f8dc88cdDocument8 pagesHubungan Tindakan Perawatan Luka Dengan f8dc88cdRD OfficialNo ratings yet

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Incisions January June 2014Document40 pagesIncisions January June 2014Raine Bow100% (1)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Financial Planning and ForecastingDocument6 pagesFinancial Planning and ForecastingMaryam UmairNo ratings yet

- ERAS - ProtocolDocument5 pagesERAS - ProtocolShakya WeeraratneNo ratings yet

- Daftar Harga Indosopha 2012 Bp. Edward Roy Palangkaraya PDFDocument5 pagesDaftar Harga Indosopha 2012 Bp. Edward Roy Palangkaraya PDFBoyke WinterbergNo ratings yet

- NCLEX Test Questions With RationaleDocument46 pagesNCLEX Test Questions With Rationaletetmetrangmail.com tet101486No ratings yet

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Cleft Lip and Palate: Current Surgical ManagementDocument3 pagesCleft Lip and Palate: Current Surgical ManagementFarisa BelaNo ratings yet

- Organizational Structure - ApolloDocument13 pagesOrganizational Structure - ApolloIpreetponnamma86% (7)

- MediCAD Brochure 2D + 3D (Except Shoulder)Document16 pagesMediCAD Brochure 2D + 3D (Except Shoulder)kocis_pNo ratings yet

- Isjna Vol 17 2 Summer 2018Document72 pagesIsjna Vol 17 2 Summer 2018Nissa KurniaNo ratings yet

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- CH 5Document153 pagesCH 5sojithesouljaNo ratings yet

- 5.2spatial Translations Administrative Office Matrix DiagramDocument3 pages5.2spatial Translations Administrative Office Matrix DiagramAthena AciboNo ratings yet

- Exam 2Document4 pagesExam 2Azra MuzafarNo ratings yet

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)