Professional Documents

Culture Documents

African Utopia

Uploaded by

Rosa O'Connor AcevedoOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

African Utopia

Uploaded by

Rosa O'Connor AcevedoCopyright:

Available Formats

African futures: The necessity of utopia

Bill Ashcroft

Department of English

University of New South Wales

Sydney, Australia

b.ashcroft@unsw.edu.au

Abstract

This article examines the utopian vision of much African writing as the dynamic

of hope generated in anticolonial struggle continues to characterise contemporary

poetry and novels. The premise is that utopia is necessary, not as mere wishful

thinking but as willed action, because, according to Paul Ricoeur, utopia is the no

place, the only place from which ideology can be countered. This means that utopia

is the only place from which the discourse of catastrophe continually undermining

Africa can be countermanded, the only place from which European history can be

subverted. The perception of a grounded utopian future requires a vision of the past,

of cultural memory freed from the confines of Western history. According to Ernst

Bloch, the doyen of Marxist utopianism, utopia cannot exist without the operation

of memory. The present is the crucial site of the continual motion by which the new

comes into being. In such transformative conceptions of utopian hope, the not-yet

is always a possibility emerging from the past. African utopianism reconsiders the

possibility of an ahistorical past, rethinks the function of memory and of time itself.

The momentum of hope not only imagines a hopeful future for Africa (crystalised

in the concept of an African Renaissance), but carries forward into a perception

of Africas impact on the world. The key to this is that the subversion of history,

the affective operation of memory and a creative vision of the future are most

powerfully conducted in African art and literature.

ISSN (Print) 1818-6874

ISSN (Online) 1753-7274

University of South Africa Press

DOI: 10.1080/18186874.2013.834557

International Journal of African Renaissance Studies

Vol. 8 (1) 2013

pp. 94114

African futures: The necessity of utopia

95

Keywords: African literature; African Renaissance; hope; Paul Ricoeur; time;

worldliness

Introduction

When we examine the discussions surrounding the future of Africa we very soon come

across the clich-ridden morass of development discourse. Well-meaning analyses of

financial and social investments, projected development goals, and improved decision

making by governments and other stakeholders fall into the trap of seeing Africa as

simply a backward version of some universal economic model, which development

would bring up to the level of the modern world. But the vision of the future projected

by African creative artists obliges nothing less than a reassessment of African modernity.

Modernity is multiple and not just one version or another of Western capitalism. But,

more importantly, the assumptions surrounding our idea of the modern involve a deeply

ingrained conception of time as linear and sequential, that African cultural production

is in an ideal position to dismantle. A circular or layered conception of time produces a

particularly resilient form of utopianism in which Africa, far from slavishly following

Europe into a wealthier future, offers the potential to envision a different kind of future

not only for itself but also for the world.

Here, Europe is used as a metaphor for the West, because Africa struggles with

the fact that the very concept of Africa takes shape in the imagination of Europe the

absolute other of the West. African writers have negotiated a perilous path between the

idea of Africa as a backward version of the West, and the negritudinist idea of Africa as

the emotive counter to the rational West, yet still employing the images and metaphors

of a traditional past to conceive a vision of the future. The task is complicated by the

fact that the very word Africa comes burdened with centuries of cultural baggage.

Utopia is therefore necessary not as mere wishful thinking, but as willed action. Utopia,

according to Paul Ricoeur, is the nowhere, the only place from which ideology can

be countered. This means that utopia is the only place from which the discourse of

catastrophe continually undermining Africa can be countermanded. Certainly, most

African nations are run by kleptocracies, but change comes not by patching broken

governments but by radically reimagining a future into which African societies can

move.

Art and literature

The cultural productions of art and literature, and indeed, creative productions in

general have an unparalleled function in providing a vision of the future, of giving

shape to willed action. Tanzanian Sam Raiti Mtamba (2011, 627) puts it somewhat

hyperbolically in his story The Pound of Flesh:

only art and literature could unlock the mysteries of life. Before men of letters there

was nothing either cabalistic or magical. It was the open sesame, the sea into which

everything flowed, the sea from which everything had its source and succour.

Bill Ashcroft

96

This is the euphoric outpouring of a man who wants to be a writer. Nigerian Chris Abani

(2007a) puts it more temperately in a talk on the stories of Africa: What we know

about how to be who we are comes from stories In other words its the agents of our

imagination who really shape who we are.

A key feature of that shaping imagination is its vision of the future. For the major

figure of Marxist utopianism, Ernst Bloch, art and literature are inherently utopian

because their raison dtre is the imaging of a different world what he calls their

Vorschein or anticipatory illumination. The anticipatory illumination is the revelation

of the possibilities for rearranging social and political relations to produce Heimat,

Blochs word for the home that we have all sensed but have never experienced or

known. It is Heimat as utopia that determines the truth content of a work of art

(Zipes 1989, xxxiii). It may lie in the future, but the promise of heimat transforms

the present. The issue is not what is imagined, the product of utopia so to speak,

the imagined state or utopian place, but the process of imagining itself. The utopian

function of literature does not mean that literary works themselves are always utopian,

nor even necessarily hopeful, but rather that the imaging of a different world in literature

is the most consistent expression of the anticipatory consciousness that characterises

human thinking. This leads him, in his magisterial The principle of hope, to the very

challenging even startling assertion that aesthetic representation produces an object

more achieved, more thoroughly formed, more essential than the immediate-sensory or

immediate-historical occurrence of this Object (Bloch 1986, 214)

Paul Ricoeur sees the utopian concept of no place as a radical contestation of what

is, indeed the only place from which ideology can be contested, and this is ideally

available through the imagination.

May we not say then that the imagination itself through the utopian function has

a constitutive role in helping us rethink the nature of our social life? Is not utopia

this leap outside the way in which we radically rethink what is family, what is

consumption, what is authority, what is religion, and so on? Does not the fantasy of an

alternative society and its exteriorization nowhere work as one of the most formidable

contestations of what is? (Ricoeur 1986, 16)

We might say that not only does imagination shape who we are, as Abani says, but

the utopian imagination helps us rethink the meaning of culture, civilisation, history,

identity. Ricoeur would see the imagination functioning beyond the aesthetic, but I

would suggest that a key dimension of the imaginative achievement, and thus the vision

of possibility offered by art and literature, is the power of affect and its connection with

hope. Take these lines from Ghanaian poet Kofi Anyidohos The Harvest of Dreams:

Though our memory of life now boils

Into vapours, the old melody of hope

Still clings to the tenderness of hearts

Locked in caves of stubborn minds

African futures: The necessity of utopia

97

The children will be home

The children will be home

The children

Those children will

Be home

Some Day (1984, 197)

While we might object that the hope expressed here has no time frame no specific

vision of the future the melody of hope by which the lines conceive heimat explains

the powerful and dynamic nature of hope that re-emerges in the work of so many African

poets and novelists.

As well as art and literature, of course, one of the most powerful mediums for

envisaging possibility in Africa has been film, particularly in Francophone colonies. As

Jean-Pierre Bekolo Obama (2009, 48) explains, Sembne Ousmane used film to open

up new perspectives with the slogan: Decolonize the screen. Thinking is speculating

with images. Cinema had a heuristic function for him, as a comparative study between

the existing, or real, and the possible (ibid., 48). Clearly, cinema was seen to conceive

the possible through the power of visual images. In the imaginative space that emerges

in this way, African viewers could project themselves into a future that they themselves

invented (ibid., 46).

History

The significance of African images of the future is that they are embedded in a past

in a way that transforms the present. This is what Edouard Glissant (1989, 64) calls a

prophetic vision of the past, which implies the possibility of an ahistorical past. Of

course Hegels notorious abolition of Africa from history is well known, but he is not

alone in this. Karl Marx thought Asiatic and African societies to be ahistorical, similar

to Slavic countries, Latin Europe and the whole of South America. The consequence of

this is that Africa, like the rest of the world, wants to enter history, because, as Ashish

Nandy (1995, 46) puts it: Historical consciousness now owns the globe Though

millions of people continue to stay outside history, millions have, since the days of Marx,

dutifully migrated to the empire of history to become its loyal subjects. When colonial

societies are historicised they are brought into history, brought into the discourse of

modernity as a function of imperial control mapped, named, organised, legislated,

inscribed. But at the same time they are kept at historys margins. The consequence

of this is the implantation of both loss and desire. Being inscribed into history is to be

made modern because history and European modernity go hand in hand. As Dipesh

Chakrabarty (1992, 19) states:

So long as one operates within the discourse of history at the institutional site of the

university it is not possible simply to walk out of the deep collusion between history

and the modernizing narratives of citizenship, bourgeois public and private, and the

nation-state.

Bill Ashcroft

98

So the nation conspires with the imperial discourse of history in conferring the holy

grail of modern being on postcolonial subjects. Nigerian Ben Okris chapter, The battle

of rewritten histories in Infinite riches depicts the struggle involved in the writing of

African history when the governor-general, clearly a symbol of the entire institution of

imperial knowledge-making, puts pen to paper:

He rewrote the space in which I slept. He rewrote the long silences of the country which

were really passionate dreams. He rewrote the seas and wind, the atmospheric conditions

and the humidity. He rewrote the seasons and made them limited and unlyrical. He

reinvented the geography of the nation and the whole continent. He redrew the

continents size on the world map, made it smaller, made it odder. (Okri 1998, 110111)

In his rewriting the governor-general wiped out Africas ancient civilisations, its

religion, spiritual dimension, its art and music, and in so changing the past he altered

our present (ibid., 110).

History and the ahistorical past

Utopia becomes necessary because it is the only place from which the ideology of

history can be contested, and the present regained. The vision of African futures then

begins in a reformulation of African pasts, and there is no better place to reaffirm a past

beyond history, than literature. This has been the way in which postcolonial writers have

represented the past: having been driven to the margins of history, postcolonial history

is habitually written through literature, by means of memory and the imagination. In

Kofi Anyidohos poetic rendition of the history of colonialism, Gods of the Pathways,

he observes that Africa stands at the crossroads at which the ahistorical past can become

the new ground for a vision of the future.

We are standing at The CrossRoads

Stranded so long Stranded

at the meeting point

of NightMare and DawnDream

Leaning against Storms

Watching horizons filled with ThunderBolts

But there are those among us

who still recall the gone years

and speak of ancient joys long buried

beneath a topsoil of bad memories. (Anyidoho 2009, 140)

The message is that the topsoil of bad memories can be swept away, that the DawnDream

can be realised.

In the celebrated Ghanaian novelist Kojo Laings (2011, 102103) Search sweet

country, Allotey offers some sage advice to Professor Sackey:

African futures: The necessity of utopia

99

We sat down and let the change, the history be thrown at us. And in spite of over five

hundred years of association with foreigners, we have been very stubborn: we have kept

our basic rhythms; we know our languages and have assimilated so much into them.

Do you really think our traditional ways were so weak that they could have been so

easily swept aside? They were too strong.

This is a resounding statement of the resilience of the ahistorical past, the power of myth

to resist history, the centrality of memory in the maintenance of culture. In Anyidohos

Gathering the Harvest Dance, he suggests that the future can only be realised by

staring history in the face:

We come today to Stare our History in the Face

We come today to Shake Hands with our Deepest Fear

We come today to exchange our Shame for Hope

Our DeepSilence for Ancestral Harvest Songs. (Anyidoho 2009, 142)

Memory and the future

In Ernst Blochs formulation of a utopian ontology, a key role is given to the category

of the not-yet as it dissolves the polarity of past and future that characterises traditional

Western ontology. While utopias are often set in the future, utopianism cannot exist

without the operation of memory. In such transformative conceptions of utopian hope

the in-front-of-us is always a possibility emerging from the past. The polarity between

past and future often seems insurmountable in European philosophy. For Plato, says

Bloch (1986, 8), beingness is beenness, and he admonishes Hegel for whom the

concept of being overwhelmed becoming. The core of Blochs (ibid., 13) ontology is

that beingness is not-yet-becomeness: From the anticipatory, therefore, knowledge

is to be gained on the basis of an ontology of the Not-Yet.

The valuing of the mythic past in the postcolonial imagination is not only an attempt

to disrupt the dominance of European history, but also an attempt to reconceive a place

in the present, a place transformed by the infusion of this past. Postcolonial utopianism

is grounded in a continual process, a difficult and even paradoxical process of

emancipation without teleology, a cyclic return to the future. The present is the crucial

site of the continual motion by which the new comes into being. In such transformative

conceptions of utopian hope the not-yet is always a possibility emerging from the

past. In traditional postcolonial societies the radically new is always embedded in and

transformed by the past.

Whereas for Ernst Bloch the utopian drive, the anticipatory consciousness is a

universal feature of human life, the utopianism of much postcolonial literature is cyclic

and recuperative. A key feature of the utopian in African literature is the intersection

of the anticipatory consciousness with cultural memory, transforming the African

imaginaire through a vision of the future grounded in a memory of the past. As Gambian

poet Tijan Sallah writes:

Bill Ashcroft

100

For stems must have roots

Dreams must seek tenacity

In lumps of savage earth.

For skies without pillars

Crumble like ancient roofs.

Skies without pillars

Crash to the dust of earth

It is in the roots that the future is planted.

We should open the shutters of the mind

To those hidden spaces of Dusty Kingdoms

For memory is roots; dreams are branches. (Sallah 1993, 9)

There can be no more powerful statement of the location of the future in memory our

Dreams must seek tenacity/ In lumps of savage earth. Memory is not about recovering

a past but about the production of possibility memory is a recreation, not a looking

backwards, but a reaching out to a horizon, somewhere out there.

Time

Memory has a complex relationship with time. Technically, the present does not

actually exist, at least not in stasis, but is always a process of the future becoming past,

becoming memory. To remember does not bring the past into the present, but the act of

remembering or the invocation of memory transforms the fluid present. Memory refers

to a past that has never been present not only because the present is a continual flow,

but because memory invokes a past that must be projected, so to speak, into the future

not only the future of its recalling, but the future of the realm of possibility itself.

This process deploys a radically transformed sense of the relation between memory

and the future:

The borderline work of culture demands an encounter with newness that is not part

of the continuum of past and present. It creates a sense of the new as an insurgent

act of cultural translation. Such art does not merely recall the past as social cause or

aesthetic precedent; it renews the past, re-figuring it as a contingent in-between space,

that innovates and interrupts the performance of the present. (Bhabha 1994, 10)

This leads me to conclude that a proper understanding of the capacity of the creative

spirit to anticipate the future requires a rethinking of the nature of time itself. We think

of time as either flowing or enduring and the dismantling of this apparent dichotomy

between succession and duration is important for utopian theory. The characteristic

of modernity with its concept of chronological empty time, dislocated from place or

human life, is a sense of the separation of past, present and future. Although the present

may be seen as a continuous stream of prospections becoming retrospections, the sense

that the past has gone and the future is coming separates what may be called the three

phases of time.

African futures: The necessity of utopia

101

Friedrich Kummel (1968, 31) proposes that the apparent conflict between time as

succession and time as duration in philosophy comes about because we forget that time

has no reality apart from the medium of human experience and thought: No single and

final definition of time is possible since such a concept is always conditioned by

ones understanding of it. As Mahmoud Darwish notes: Time is a river / blurred by the

tears we gaze through.

While we think of time as either flowing or enduring, Kummel makes the point that

duration without succession would lose all temporal characteristics. A theory of time

therefore must understand the correlation of these two principles. Duration arises only

from the stream of time and only within the background of duration is our awareness of

succession possible. The critical consequence of this is that

[i]f something is to abide, endure, then its past may never be simply past, but must in

some way also remain present; by the same token its future must already somehow

be contained in its present. Duration is said to exist only when the three times (put

in quotation marks when used in the sense of past, present and future) not only follow

one another but are all at the same time conjointly present the coexistence of the

times means that a past time does not simply pass away to give way to a present time,

but rather that both as different times may exist conjointly, even if not simultaneously.

(Kummel 1968, 3536)

Now what interests me about this is that such an experience of time is already present in

African literature. This is particularly so in the novel, the crucial characteristic of which

is its engagement with time. Stories offer the progress of a world in time and thus can

become narratives of temporal order. But magically, by unfolding in time they take us

out of time. It may be that narrative, whose materiality is isomorphic with temporality,

provides a way (though not the only way) of communicating different experiences of

time. One way of communicating a different knowledge of time is through circular

time developed from the forms of oral story-telling, in which then and now are in

constant dialogue.

We can see this layered time throughout African literature, from the scene of the

egwugwu in Things fall apart, who are the actual mythic ancestors of the village and

at the same time the recognisable elders dressed up to dance. The layering of time

continues to the present in a passage from Kojo Laings Search sweet country when Kofi

Loww stands in the market:

He stood still caught in perfect African time time that existed in any dimension and

blocking the paths of other sellers with the same time that brought ancestors to the

market, that touched the eyes of sellers and buyers now, that moved beyond those yet to

be born. (Laing 2011, 156)

In a fascinating poem Anyidoho links the circular African time to the rhythm of the

drums, which lead in a backwards-forwards dance. Ultimately the rhythm of the dance

is the rhythm of time itself. Africa is centred in a union of time and sound and silence, a

circular time in which the future and past are lodged in and energise the present.

Bill Ashcroft

102

And The Drums

The Drums guide our Feet

In this backwards-forwards Dance

This Husago Dance

This Dance into a Future

That ends in the Past.

Two steps Forward

to where Hope

rises like RainBows.

One step Backward

to where Sorrow

falls like Tropical ThunderStorms.

And Africa

Africa leans against the Storms

Leaning against the Future

Like a Warrior

Tired from Historys BattleFields. (Anyidoho 2009, 134)

The poet goes on to invite us to come with him across the Birth of Time in a union of

sound and silence. The rhythm of the drums becomes a powerful image of layered time,

because drums in Anyidoho have the powerful role of enfolding, collapsing time. In his

poem The Return he takes on the persona of the Creator who made a new world filled

with gods and goddesses who soiled their glory/ with passions unfit for dogs. So he

made a newer world peopled with human beings. The poem ends with the lines:

Call back here those Old Drummers

Give them back those broken drums with nasal twangs

Let them put New Rhythms to the Loom

And weave New tapestries for your Gliding Feet

The Birth of a New World demands the Graceful Dance of Life

Now there is still some Laughter in your Souls

Your feet with skill must teach your Hearts

To weave the Graceful Dance of Life

The Ancestral Primordial Dance of Birth. (ibid., 136)

So the dance of life, which is beaten by the drums, is the birth of a new world. Anyidoho

further develops this interpenetration of past, present and future in the images of the

rope or creeper or birth cord which symbolise time, the different generations bound

together by the creeper rather than separated by the line of history. The ancestors are like

the seed that gives birth to the creeper, linking together the past and present members of

the clan (ibid., 10); the weaving of a rope represents tradition. In a wider sense, the rope

or creeper is the image of life itself and in particular of mans regenerative faculties: the

African futures: The necessity of utopia

103

weaving of the rope is also a reminder of the importance of procreation, the foremost

duty of every man (ibid., 12). And the procreation of children is linked, in the Ewe

vocabulary, to the creation of poetry and music (ibid., 547). In his paper on Ewe funeral

poetry, Anyidoho (1984, 2122) states:

All the activities generated by death, all the rites, the ceremonies, the funeral dance

and song, may be seen as properly motivated by one overriding desire the desire to,

perpetuate life in spite of and because of death [...]. The dead continue to live not just in

spirit but also in the artistic tradition [...]. The ultimate reality that rules the universe [...]

is lifes permanence in various transformations even beyond death.

Here we find a powerful statement of the cultural underpinning of African hope and the

location of the future in the present.

Hope

The origin of African utopianism lies in the resilience of memory, particularly of the

ancient joys buried deep beneath the topsoil of bad memories (Anyidoho 2009, 140).

It does this because memory refuses to recognise the distinction between duration and

succession. But African utopianism found its most powerful expression in the persistence

of hope for freedom from colonial oppression. In most cases the vision was for an

independent state, which led to great disillusionment as the post-independence nation

simply moved in to occupy the structures of the colonial state. But the dynamic of hope

generated by anticolonial writers produced the energy for future thinking throughout the

subsequent bitter realisation of post-independence failure.

One of the most powerful voices of hope in the pre-independence period was that of

Aghostino Neto, whose cry against the repressive Portuguese regime of Angola stands

as a benchmark for the persistence of hope for freedom, and the clarity of a vision for

the future. Netos road to the future passes through prison, exile, torture, and the death

of close friends, but it is sustained by the certainty of hope. His collection Sacred hope

lodges the cry for freedom in something much deeper than the nation state. This I think is

the source of the power of this poetry, because the cry of freedom expresses the dynamic

of hope that continues to project into the future. As Basil Davidson (Introduction in

Neto 1974, vii) states: He is followed or opposed as the leader of a struggle for the

future, a struggle that all men must fight for their different times and places, and all

women too, shaking off the past, transforming the present. This is a salutary reminder

that despite the disappointments of subsequent national regimes in Africa, the vision of

heimat still persists and the dynamic of hope is one that continues to drive its creative

writers. Neto can say on behalf of all African writers: I am a day in a dark night/ I am

an expression of yearning (Neto 1974, viii).

Some of the energy for this sense of irrepressible hope comes from the poets task

of speaking on behalf of other oppressed people in the colony. This is not so much the

voice of the seer as the voice of one who knows that his sufferings and hopes are shared.

Bill Ashcroft

104

For Neto hope is not a vague wish but something grounded in action, a sense of the

future grounded in the present.

Tomorrow we shall sing anthems to freedom

When we commemorate

The day of the abolition of this slavery

We are going in search of light

Your children Mother

(all black mothers

whose sons have gone)

They go in search of life (ibid., 12)

The words of Netos translator are apposite here, namely that the pressing need is not

to preserve elements of the past which are being shattered by the present, but to release

the future imprisoned in the present (ibid., xxxviii). In the poem Saturday Night in the

Muceques (the poor districts of Luanda where Africans live), after listing the forms of

anxiety oppressing the people he says:

In men

Seethes the desire to make the supreme effort

So that Man

May be reborn in each man

And hope

No longer becomes

The lamentation of the crowd (ibid., 9)

In the poem bleeding and germinating we find that out of blood and suffering germinate

hope, peace and love:

Our eyes, blood and life

Turned to hands waving love in all the world

Hands in the future smile inspirers of faith in

The vitality

Of Africa earth Africa human

Of immense Africa

Germinating under the soil of hope

Creating fraternal ties in freedom of desire

Of anxiety for concord

Bleeding and germinating

For the future here are our eyes

For Peace here are our voices

For Peace her are our hands

Of Africa united in love. (ibid., 43)

African futures: The necessity of utopia

105

It is possibly only in the context of Netos history of imprisonment and torture that

the euphoria of this rhetoric can be understood. This combination of the sacred, love

and the ahistorical reality of Africa, recurs in Chris Abanis devastating novel about

child soldiers, Song for night, when My Luck, the 15-year-old child soldier, discovers a

mysterious lake and asks its equally mysterious guardian:

And this lake is real? ... I dont understand.

Nobody does. Everybody does. It is real because it is a tall tale. This lake is the heart of

our people. This lake is love. If you find it, and find the pillar, you can climb it into the

very heart of God, he said. (Abani 2007, 69)

Like Neto, Abani was imprisoned, tortured and exiled, but the lake offers a vision of

Africa that perhaps only literature and its various tall tales can provide. Nevertheless

such magical real images may, as Ricoeur states, have a constitutive role in helping us

rethink the nature of our social life. Although the persistence of hope is modelled in

Neto we find it throughout African literature as a dynamic and necessary foundation

for the vision of the future. As Ghanas most famous poet, Kofi Awoonor, writes in A

Death Foretold:

I believe in hope and the future

of hope, in victory before death

collective inexorable, obligatory;

I believe in men and the gods

in the spirit and the substance,

in death and the reawakening

in the promised festival and denial

in our heroes and the nation

in the wisdom of the people

the certainty of victory

the validity of struggle (Awoonor 1991, 445)

When thinking of the revolution that Neto and others hoped for, we must remember

that revolution has two meanings: it is not simply a revolt but a revolving, a spiral

into the future. Seeing this, we can understand that the belief in the future does not

stop with independence it remains part of the continuous spiraling of hope. Even if

independence comes, and hope has been disappointed, creative work continues to spiral

into the future, continues the revolution. That movement into the future must first be a

movement of the imagination.

This is true of Africa (as it is more recently of the Arab Spring). Imagined futures

have continued in a spiral of revolutionary hope. If we consider novels such as Achebes

A man of the people (1966), Soyinkas The interpreters (1965), and Armahs trilogy of

despair The beautyful ones are not yet born (1968), Fragments (1970), Why are we so

blessed? (1972) and many other novels of these decades, including Ngugis Petals of

blood (1977) and Devil on a cross (1982), we might think of the post-independence period

Bill Ashcroft

106

as one of hope destroyed. Sembene Ousmane presented a Pan-African Marxist utopia in

the film Xala in 1974, which by the end of the century was seen to be unrealisable. But

the 2006 film Bamako, by Abderrahmane Sissako, offered something no less ambitious

than Xala. The World Bank and IMF are put on trial in a courtyard in the capital of Mali.

The prosecution witnesses report how the structural adaptation measures imposed by

these organisations impact everyday life in Africa: the cuts in education, the privatisation

of water management, the dismantling of the railway network, to name a few.

The point about this is that the trajectory of African hope and its vision of the future

came increasingly to look outward, and this corresponds to something developed out

of the dynamic of hope what Ernst Bloch calls concrete utopia. Bloch makes a

distinction between abstract utopia or wishful thinking that is merely fantastic, and

concrete utopia, the outcome of wishful thinking passed into willful action. For him,

the unfinished nature of reality locates concrete utopia as a possible future within the

real; and while it may be anticipated as a subjective experience, it also has objective

status (Levitas 1990, 89). Or, as Neto (1974, 12) puts it: He who has strived has not

lost/ But has not yet won.

In the same vein, Laurence Davis (2012, 127) contends that critics and defenders

of utopia alike have tended to conceive of utopia primarily as a transcendent and fixed

ought opposed to the is of political reality and the was of social history, but it

may also be understood as an empirically grounded and open-ended feature of the real

world of history and politics representing the hopes and dreams of those consigned to

its margins.

Grounded utopias both emerge organically out of and contribute to the further

development of, historical movements for grassroots change. As a result, they are

emphatically not fantasized visions of perfection to be imposed upon an imperfect

world, but an integral feature of that world representing the hopes and dreams of those

consigned to its margins. (Davis 2012, 136137)

The key to grounded utopias, as integral to the real world, and particularly to the drive

for change, transformation and revolution in the colonial context, is the question of

representation because, as the history of colonial domination demonstrates, the most

powerful form of oppression is not military control or the carceral function of the state,

but the control of representation. This is the point at which wishful thinking transfers

into willful action.

Worldliness

Perhaps the most fertile field for grounded utopianism is the dimension of African

worldliness, or its place in and upon the world. This plays out in several ways: there is

the vision of Africas political, cultural and spiritual impact on the world; there is the

history of Afro-modernity and pan-Africanism; and in contemporary writing a vision of

a mobile and transnational Africa.

African futures: The necessity of utopia

107

In Netos poetry it is the vision of Africa in the world and not simply freedom from

Portuguese rule that begins to transfer wishful thinking into wilful action. His poetry is

avowedly political and there is a sense of the future beyond the immediate attainment

of a nation. He writes:

Now is the time to march together

bravely

to the world of

all men. (Neto 1974, 30)

This suggests something that comes to be taken up by writer after writer in Africa the

desire to enter the world of all men, the world of an Africa that is no longer formed in

the imagination of Europe. This is the ultimate meaning of the Reconquest:

Let us go with all of humanity

To conquer our world and our peace. (ibid., 40)

Neto is profoundly internationalist and this is why he is seen as a key figure in the

African vision of the future. Although profoundly Angolan, profoundly African and

passionately devoted to political liberty, his poems reach beyond Africa. In Sculptural

Hands he writes:

I see beyond Africa

love emerging virgin in each mouth

in invincible lianas of spontaneous life

and sculptural hands linked together

against the demolishing waterfalls of the old

Beyond this tiredness in other continents

Africa alive

I feel it in the sculptural hands of the strong who

are people

and roses and bread

and future. (ibid., 49)

While in A Succession of Shadows he writes:

Here are our hands

Open to the fraternity of the world

For the future of the world

United in certainty

For right for concord for peace. (ibid., 23)

In the poem with equal voice Neto (1974) offers a rousing call for reconstruction, for

(African) men who (as slaves) built the empires of the West/ the wealth and opportunities

Bill Ashcroft

108

of old Europe people of genius heroically alive now building our homeland/ our

Africa. The poem calls for Africans to re-encounter Africa, to resuscitate man:

From chaos to the worlds new beginning

To the progressive start of life

And enter the harmonious concert of the universal

In dignity and freedom

Independent people with equal voice

As from this vital daybreak over our hope. (ibid., 84)

We can see the vision in which Africa has the potential to change the world repeated in

Ben Okris Infinite riches where, having described the way in which Africa was brought

into history, he proceeds to imagine a counter-history. Here a layering of different orders

of time now projects into a future in which cultural memory can interpolate and disrupt

global history. This occurs when the old woman of the forest weaves the secret history

of the continent. As the novel unfolds, the immense energy of her retelling and thus

re-historicising a different kind of Africa, produces a (pan) Africa that is not only vast

but powerful in its potential effect on the entire world. For the history she weaves is

[f]rightening and wondrous, bloody and comic, labyrinthine, circular, always turning,

always surprising, with events becoming signs and signs becoming reality (Okri 1998,

112).

This is more than a history, it is a laminating of different orders of time. The old

woman codes the secrets of plants, the interpenetrations of human and spirit world, the

delicate balance of forces:

She even coded fragments of the great jigsaw that the creator spread all over the diverse

peoples of the earth, hinting that no one race or people can have the complete picture

or monopoly of the ultimate possibilities of the human genius alone. With her magic

she suggested that its only when all peoples meet and know and love one another that

we begin to get an inkling of this awesome picture, or jigsaw, or majestic power. The

fragments of the grand picture of humanity were the most haunting and beautiful part of

her weaving that day. (ibid., 112113)

This is a richly utopian view of the capacity of the African imaginary to re-enter and

reshape the modern world. It is not merely a hope for African resurgence, but a vision

of Africas transformative potential, a potential that will be realised as the teleological,

expansionist and hegemonic tendencies of the West are gradually subverted. In one

sense Infinite riches is an attempt to show the scope of that cultural possibility by

infusing the language of excess with the enormously expanded vision of the horizons of

African cultural experience.

Afro-modernity and Pan-Africanism

Neto and Okri saw Africa impacting on the world through the dynamic of hope, but the

recirculation of a shared sense of oppression and purpose back to newly independent

African futures: The necessity of utopia

109

African states is one of the more concrete consequences of the African Diaspora. The

emergence of the New Negro and calls for transnational solidarity were heard in Ghana

and underpinned Kwame Nkrumahs demand for a free Africa.

We see in a statement by the African-American formulator of pan-Africanism,

Alexander Crummel, the beginnings of what I take to be a revolution in the postcolonial

relation between memory and anticipation:

What I would fain have you guard against is not the memory of slavery, but the constant

recollection of it, as the commanding thought of a new people, who should be marching

on to the broadest freedom in a new and glorious present, and a still more magnificent

future. (Crummel 1969, 13)

Crummels desire exemplifies a strategic utopianism that comes to be one of the most

powerful instances of the postcolonial transformation of modernity. Where Western

modernity became characterised by openness to the future we see now a situation in

which that openness is revolutionised by the political agency of memory. These various

features of Afro-modernity: its supra-national character; its circulation and recirculation

of liberating discourses of identity; its recovery of history in a vision of the future are all,

incidentally, features of the utopian in African literature, features shared and augmented

by a growing utopianism in other post-colonial literatures.

In Harvest Dance, Kofi Anyidoho calls on Africans to reach out to the world:

So raise your arms Brothers

Stretch your hands Sisters

Reach your hand to the BrotherMan from Birmingham in Alabama still

Standing Tall with Wonder in his Eyes

Stretch your arm to the Sister from SouthSide Chicago still

Standing Firm against the Hostile Winds

Stretch your eyes to that Tender Child from Harlem in Nu York wearing a

Rainbow for her Hair

Embrace that Grand Mama from San Salvador de Bahia

And yes that Hell of a Guy from KingstonTown in Jamaica

From GeorgeTown in Guyana and From Barranquilla in Colombia.

From CapeTown in MandelaLand and From Addis Ababa in Abyssinia.

From Kumbi-Saleh of AncientTimes and from Timbuktu of Ancestral Dreams.

(Anyidoho 2009, 142)

Transnational Africa

At the heart of this vision of a pan-African world, beats the energy of a growing

transnationalism. Like Caribbean literature, African literature finds itself increasingly

emerging from London and New York, and no less African for that. Chimamanda

Adiche, Chris Abani and Kojo Laing, prominent contemporary examples of this, spend

time moving between Nigeria or Ghana and the West.

Bill Ashcroft

110

Adiches latest novel Americanah moves between the United States, United

Kingdom and Nigeria a mobility that allows her to poke fun at the super-sensitivity of

Americans about race. Friends are dress-shopping in the novel and when they go to pay,

the cashier asks which of two saleswomen helped them, but theyre not sure. She lists

numerous physical characteristics to identify the salesperson before giving up. Why

didnt she just ask Was it the black girl or the white girl? Ifemelu exclaims after they

leave. Because this is America, her friend tells her. Youre supposed to pretend that

you dont notice certain things. The ironic and superior tone is interesting here, but the

relationship of contemporary African writers to the West is ambivalent, to say the least,

as these contemporary worldly narratives nevertheless appear to look to the West, to

history, desiring inclusion.

Chris Abanis work is a commentary on the violence, poverty and oppression in

Africa, first in the images of child soldier in Song for night and in a familiarly dystopian

view of Lagos in Graceland. While he does not use the words hope or utopia, Abani

(2004a; Aycock 2009) often talks about transformation and possibility, even though the

transformation sometimes involves reaching the sublime through the grotesque. On

his website he calls himself a zealot of optimism, despite the violence, darkness and

indeterminacy of his accounts of Nigeria. In his talk on the Stories of Africa he says: I

am asking us to balance the idea of our complete vulnerability with the complete notion

of transformation ... (Abani 2007a).

So, for Abani transformation is a key, even though the idea of America as utopia

is a troubling one. Youthful protagonists like My Luck in Song for night and Elvis

in Graceland are ideal subjects for transformation, because identity and agency are

negotiated through discovery and possibility. But the euphoric optimism that pervades

Graceland even in the face of the horror of Lagos is deeply problematic because it is

generated by the possibility of America as utopia. For Elvis, who is given a passport by

his friend Redemption, America is redemption: Yes, this is redemption, he says as they

call his name. This is unsettling because the implication is that utopia lies, like Elviss

dancing, in a simulation of America and its popular culture. For Omelsky (2011, 85) the

ambiguous politics of Graceland is a strategy:

Abani deploys ambivalence as a discursive vehicle with which to expand the contours

of how we come to think and imagine African youth resistance pressing us to consider

the inherent contradictions, complicities and contingencies that perhaps accompany any

ascription of agency.

This seems supported by Abanis comment on this aspect of the novel:

Its a story about a loss of innocence, and yet that being some sort of redemption. Its

already a lie. Healing, or any kind of transformation or transubstantiation is never an

erasure of the trauma, but its the attempt to cobble together damaged self, that can limp

through in a very beautiful way. Its not America thats important, or that hes coming

to it, its that hes able to have that moment of transfiguration right there at the end.

(Aycock 2009, 8)

African futures: The necessity of utopia

111

Perhaps we will have to take Abanis word for it. It is not America that is important but

the moment of transfiguration the very idea that such transformation is possible that

generates a utopian vision of the future. The thing that holds this idea in place is that

[i]dentity is a destination and thats why all of my work is about becoming. Were

all transnational, either in the real sense of a passport, where youve lived in different

countries and have spent life migrating through different continents, or in the way in

which culture mixes. (ibid., 8)

Whether Elvis achieves it or not, Abanis concept of African worldliness is utopian.

For him the impact of Africa on the world is simply in being there. But while Abanis

understanding of culture and identity is exemplary I am not entirely convinced by

Elviss transfiguration, and I think both Adiche and Abani are caught in the paradoxical

trap of cosmopolitanism a trap that opens where ideology and utopia meet. There is

a cosmopolitanism of the sophisticated global traveller, the elite cultural producer and

there is the mobility of the ordinary subject. The ethical dimension of cosmopolitan

theory is its great strength and I admire its utopian orientation. But it does not solve the

problem of who can be allowed into the cosmopolitan club. Part of the problem here

is the temporal linearity of the Bildungsroman. Elvis is headed for escape rather than

redemption, and while transubstantiation is never an erasure of the trauma, memory

and the past are merely things to be overcome rather than a recollection through which

the future takes shape.

A better term, perhaps, is one that avoids the question of inclusion to see mobility

as both a spatial and metaphoric function of subjectivity itself. This is the concept of

the transnation (Ashcroft 2010), which perhaps better captures the intent of Abanis

claim that we are all transnational. The concept of transnation does not refer to an

object in space but to a way of understanding subjects beyond normative formulations

of the nation the fluid, migrating outside of the state that begins within the nation.

One writer who avoids the trap of cosmopolitanism, despite his energetic espousal of

syncreticity, is Kojo Laing. In Search sweet country he avoids the trap because his

utopia is not the promise of a cosmopolitan future but a space of transformation that

exists within language itself, making the novel both very worldly and very local. Accra

is multifaceted and multivoiced, a rhizomatic interplay of border-crossings, which is the

key to the novels perception that growth, change and mobility are already part of the

life of the transnation.

I once asked Chris Abani Where is home? and his very prescient reply was that

home is in language. I want to extend that to suggest that heimat, that is, the home

we have sensed but not yet experienced, the utopian no place, may be achieved in

language. Kojo Laing reveals that not just the future, but the future of Africa in the

world, the future of African worldliness, may lie in the capacity of language to disrupt

accepted ideas of nation or culture by the circulation of difference. The appropriation

and transformation of English informed by the grammar and syntax of the vernacular

is a fundamental strategy of postcolonial writing. But Laings language is much more

than this, for while he does include Ga names, and other Ghanaian terms from various

112

Bill Ashcroft

sources, and while there is evidence that he uses a poetic syntax that is typical (with

variations) of both poetry and oratory in Akan and Ga (Dakabu and Kropp 1993, 23)

his language is fundamentally comic a comic disruption of the cultural space between

languages.

The two beards crowded in one corner of Accra did not agree The fathers beard

shifted and pulled at different angles, taking in the sun and folding its rays under the hair

The sons beard was soft and vast with Vaseline, the hair parting ways at the middle

... Both beards were, in the brotherhood of hair, heavy with commas (Laing 2011, 2)

The utopian element of Search sweet country lies in the displacement of linear narrative

as it is overwhelmed by a proliferation of subject positions. The national story is

many individual stories, a transnation in which the overlapping multitude of stories

overwhelms the borders of history and even time itself.

Beni Baidoo was Accra, was the bird standing alive by the pot that should receive it, and

hoping that, after being defeathered, it would triumphantly fly out before it was fried.

(ibid., 1)

He represents not just language but the failure of language, which is one of the novels

major themes: in the past he had been a clerk (but never of the first division) and an

unsuccessful letter-writer; now he is desperate, indiscriminate talker, obsessed with

founding a village, a town of his own, but unable to find a more solid building material

than words. But this is part of the point of the novel that the utopia of the syncretic can

be achieved in words.

For Laing identity is not so much a destination as a dialectical process. He holds

passionately that the search for wholeness involves change, cultural and social interaction

between Europe and Africa (Cooper 1998, 179). But Woman of the aeroplanes offers

a relationship with Europe far beyond an ambiguous cosmopolitanism. By employing

a comic language, completely disrupting, even eviscerating, the linearity of narrative,

Laing layers time and circumvents history with a constantly embedded past that enters

a dialectical process with Europe. This emerges in the exchanges between the Ghanaian

town of Tukwan and Scottish Levensvale, both doubly oppressed and marginalised.

This novel, balanced as it is between two marginal spaces, undermines the idea of the

West as a shimmering utopian goal, and also reveals the transnation as operating both

within, beyond and between borders.

Like Tukwan, Levensvale has to transform itself. First it has to become human by

purging itself of racism and colonising practices. Second, it has to become economically

viable and independent. The material and the spiritual are complementary, like the two

towns, the twin brothers and the twin aeroplanes:

So both towns wanted a prosperity of pocket to go with the reincarnating prosperity of

the soul, as if to remain mortal took too long, and that money would shorten things a

bit. (Laing 1988, 92)

African futures: The necessity of utopia

113

Like lovers, the towns must entwine and embrace, syncretise and mix:

Now since a snore in Levensvale could originate in Tukwan, and since an elbow in

Tukwan could have its counterpart in Levensvale, everybody was free to be and do what

he or she liked. There was a blast of freedom from the freely-mixed bodies and worlds,

ampa. (ibid., 86)

Despite the magical real dimension of Woman of the aeroplanes, Tukwan, according to

Laing, is realistically possible in terms of cross cultural interchange. In terms of hope

it is a realizable utopia (Cooper 1998, 195). It is realisable because it is grounded,

not a fantasized vision of perfection to be imposed upon an imperfect world, but an

integral feature of that world representing the hopes and dreams of those consigned to

its margins (op.cit.). Tukwan is realisable in terms of the circularity of time and space it

sets in motion within the story of cultural interchange. In the future of Africas contact

with Europe, both must be transformed. Transformation of the future emerges out of the

transformative layering of past and present, for this may be the only way in which the

empire of history may be resisted and the grounded utopia of a worldly African future

be realised.

African visions of the future, then, are driven by the dynamic of hope, which

took shape in the experience of colonisation, but continues through an anticipatory

consciousness that is grounded in ahistorical memory. They emerge out of an empowering

experience of layered time that envisages an impact on the world. Utopia is necessary

because it is only from the no-place of a utopian future that ideology particularly the

teleological ideology of history can be contested. What remains remarkable about

African literature and cultural production is the stunning tenacity of its hope and its

grounded vision of possibility.

References

Abani, C. [2004] 2005. Graceland. New York: Picador.

Abani, C. 2007. Song for night. Melbourne: Scribe.

Abani, C. 2007a. Chris Abani on the stories of Africa (TED) http://www.ted.com/talks/chris_

abani_on_the_stories_of_africa.html (accessed 1 September 2013).

Anyidoho, K. 1984. Harvest of Our Dreams, with Elegy for the Revolution. London: Heinemann.

Anyidoho, K. 2009. The return. Black Renaissance 9 (Winter): 1.

Ashcroft, B. 2010. Transnation. Re-routing the postcolonial: New directions for the new

millennium, ed. J. Wilson, C. Sandru and S. Lawson, 7285. London: Routledge.

Awoonor, K. 1991. A Death Foretold. The Literary Review 34(4)(Summer): 445446.

Aycock, A. 2009. An interview with Chris Abani. Safundi: The Journal of South African and

American Studies 10(1): 110.

Bekolo Obama, J-P. 2009. Africa for the future: Sortir un nouveau monde du cinma. Achres

(France), Yaound (Cameroon): Dagan & medYa.

Bhabha, H. 1994. The location of culture. London: Routledge.

Bloch, E. 1986. The principle of hope. Three vols. Trans. N. Plaice, S. Plaice and P. Knight.

Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

114

Bill Ashcroft

Bloch, E. 1989. The utopian function of art and literature: Selected essays. Trans. J. Zipes and

F. Mecklenburg. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Chakrabarty, D. 1992. Post-coloniality and the artifice of history: Who speaks for the Indian

pasts. Representations 37(Winter): 126.

Cooper, B. 1998. Magical realism in West African fiction. London: Routledge.

Crummel, A. 1969. Africa and America: Addresses and discourses. Miami: Mnemsonyne.

Dakabu, M. and E. Kropp. 1993. Search sweet country and the language of authentic being.

Research in African Literatures 24(1)(Spring): 1935.

Darwish, M. 2002. A state of siege. http://www.arabworldbooks.com/Literature/poetry4.html

(accessed 2 May 2013).

Davis, L. 2012. History, politics and utopia: Toward a synthesis of social theory and practice.

Existential utopia: New perspectives on utopian thought, ed. P. Vieira and M. Marder,

127140. London: Continuum.

Glissant, E. 1989. Caribbean discourse: Selected essays. Trans. and introd. J.M. Dash.

Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia.

Kummel, F. 1968. Time as succession and the problem of duration. The voices of time, ed. J.T.

Fraser, 3155. London: Allen Lane.

Laing, K. 1988. Woman of the aeroplanes. London: Heinemann.

Laing, K. 2011. Search sweet country. San Francisco: McSweeney.

Levitas, R. 1990. The concept of utopia. New York: Phillip Allen.

Mtamba, S.R. 2011. Areas of shade, areas of darkness: Poems and stories. Spheres public and

private: Western genres in African literature (Matatu 39), ed. G. Collier, 604. Amsterdam

and New York: Rodopi.

Nandy, A. 1995. Historys forgotten doubles. History and Theory 4(2)(May): 4466.

Neto, A. 1974. Sacred hope. Trans. M. Holness. Dar es Salaam: Tanzania Publishing House.

Okri, B. 1998. Infinite riches. London: Phoenix House.

Omelsky, M. 2011. Chris Abani and the politics of ambivalence. Research in African Literatures

42(4)(Winter): 8496.

Ricoeur, P. 1986. Lectures on ideology and utopia, ed. G.H. Taylor. New York: Columbia

University Press.

Sallah, T. 1993. Dreams of dusty roads. Boulder, CO: Three Continents.

Zipes, J. 1989. Introduction: Toward a realization of anticipatory illumination: Ernst Bloch, The

utopian function of art and literature: Selected essays. Trans. J. Zipes and F. Mecklenburg.

Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Copyright of International Journal of African Renaissance Studies is the property of

Routledge and its content may not be copied or emailed to multiple sites or posted to a listserv

without the copyright holder's express written permission. However, users may print,

download, or email articles for individual use.

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Santiago Castro-Gómez - Critique of Latin American Reason-Columbia University Press (2021)Document353 pagesSantiago Castro-Gómez - Critique of Latin American Reason-Columbia University Press (2021)Rosa O'Connor AcevedoNo ratings yet

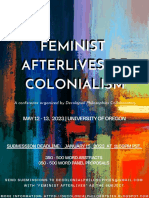

- Feminist Afterlives of Colonialism, May 12-13 - ProgramDocument4 pagesFeminist Afterlives of Colonialism, May 12-13 - ProgramRosa O'Connor AcevedoNo ratings yet

- Feminist Afterlives of Colonialism Poster (Final-)Document1 pageFeminist Afterlives of Colonialism Poster (Final-)Rosa O'Connor AcevedoNo ratings yet

- The Golden Gulag Table of ContentDocument3 pagesThe Golden Gulag Table of ContentRosa O'Connor AcevedoNo ratings yet

- Feminist Afterlives of Colonialism CFP FINALDocument3 pagesFeminist Afterlives of Colonialism CFP FINALRosa O'Connor AcevedoNo ratings yet

- Guinea and Cabo Verde Against Portuguese Colonialism. Cabral S Speech.Document12 pagesGuinea and Cabo Verde Against Portuguese Colonialism. Cabral S Speech.Rosa O'Connor AcevedoNo ratings yet

- Caribbean Philosophical Association Conference Offers Insightful DiscussionsDocument16 pagesCaribbean Philosophical Association Conference Offers Insightful DiscussionsRosa O'Connor AcevedoNo ratings yet

- CFP Flyer - 2Document1 pageCFP Flyer - 2Rosa O'Connor AcevedoNo ratings yet

- Ernst Fischer, Franz Marek - How To Read Karl Marx (1996)Document99 pagesErnst Fischer, Franz Marek - How To Read Karl Marx (1996)Rosa O'Connor AcevedoNo ratings yet

- CFP FlyerDocument1 pageCFP FlyerRosa O'Connor AcevedoNo ratings yet

- Angel L Opez-Santiago HE Ntillean EagueDocument14 pagesAngel L Opez-Santiago HE Ntillean EagueRosa O'Connor AcevedoNo ratings yet

- Rise and Fall of Haiti's Duvalier DictatorshipDocument15 pagesRise and Fall of Haiti's Duvalier DictatorshipRosa O'Connor AcevedoNo ratings yet

- T W Adorno TimelineDocument2 pagesT W Adorno TimelineRosa O'Connor AcevedoNo ratings yet

- The State of Exception and The Puerto Ri PDFDocument24 pagesThe State of Exception and The Puerto Ri PDFRosa O'Connor AcevedoNo ratings yet

- Sylvia Federici On DebtDocument14 pagesSylvia Federici On DebtRosa O'Connor AcevedoNo ratings yet

- Andy Clark - Being There (Putting Brain, Body and World Together)Document240 pagesAndy Clark - Being There (Putting Brain, Body and World Together)Nitin Jain100% (11)

- Andy Clark - Being There (Putting Brain, Body and World Together)Document240 pagesAndy Clark - Being There (Putting Brain, Body and World Together)Nitin Jain100% (11)

- Ford Fellowship Program for Diversity in College TeachingDocument4 pagesFord Fellowship Program for Diversity in College TeachingRosa O'Connor AcevedoNo ratings yet

- SEO-Optimized Insights on Emotions, Relationships and Well-BeingDocument17 pagesSEO-Optimized Insights on Emotions, Relationships and Well-BeingRosa O'Connor AcevedoNo ratings yet

- Devitt 1Document26 pagesDevitt 1Rosa O'Connor AcevedoNo ratings yet

- Why Abyei Matters The Breaking Point of Sudan'S Comprehensive Peace Agreement?Document20 pagesWhy Abyei Matters The Breaking Point of Sudan'S Comprehensive Peace Agreement?Rosa O'Connor AcevedoNo ratings yet

- Intencionalidad - Articulo.chalmers - Critica.are There Endenic Grounds ...Document17 pagesIntencionalidad - Articulo.chalmers - Critica.are There Endenic Grounds ...Rosa O'Connor AcevedoNo ratings yet

- Boliva Under MoralesDocument14 pagesBoliva Under MoralesRosa O'Connor AcevedoNo ratings yet

- Denoted by The Definite Description. If There Is No Object That Is So-And-So, or More ThanDocument9 pagesDenoted by The Definite Description. If There Is No Object That Is So-And-So, or More ThanRosa O'Connor AcevedoNo ratings yet

- Shapiro The Embodied Cognition Research ProgrammeDocument9 pagesShapiro The Embodied Cognition Research ProgrammeKessy ReddyNo ratings yet

- Tweyman - The Logic of Hume's PDFDocument8 pagesTweyman - The Logic of Hume's PDFRosa O'Connor AcevedoNo ratings yet

- Why I Left Harvard University PDFDocument6 pagesWhy I Left Harvard University PDFRosa O'Connor Acevedo100% (3)

- Ford Fellowship Program for Diversity in College TeachingDocument4 pagesFord Fellowship Program for Diversity in College TeachingRosa O'Connor AcevedoNo ratings yet

- Boliva Under MoralesDocument14 pagesBoliva Under MoralesRosa O'Connor AcevedoNo ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Anarchy in International Rlations PDFDocument26 pagesAnarchy in International Rlations PDFArzu Zeynalov100% (1)

- What is Socialism, What is Capitalism, What is Communism, Difference Between Socialism and Capitalism, Critiques of Socialism and Capitalism, Simple Explanation of Socialism and Capitalism, Pros and Cons of Communism & SocialismDocument4 pagesWhat is Socialism, What is Capitalism, What is Communism, Difference Between Socialism and Capitalism, Critiques of Socialism and Capitalism, Simple Explanation of Socialism and Capitalism, Pros and Cons of Communism & SocialismAmit Kumar100% (1)

- UntitledDocument228 pagesUntitledСаша ШестаковаNo ratings yet

- Contra CulturaDocument1 pageContra CulturarazvantiutiucaNo ratings yet

- UN Declaration and Philippine Laws on Gender Equality and Women's RightsDocument22 pagesUN Declaration and Philippine Laws on Gender Equality and Women's RightsMeYe OresteNo ratings yet

- Status of Closed Bank Branches in PakistanDocument8 pagesStatus of Closed Bank Branches in PakistanMajidAli TvNo ratings yet

- The Case of Baby Jane DoeDocument2 pagesThe Case of Baby Jane DoeAlizah Lariosa BucotNo ratings yet

- FESCO Telephone DirectoryDocument7 pagesFESCO Telephone DirectoryKashifNo ratings yet

- Proclamation of Independence, 17 April 1971: East West University GEN 226 / Lecture 17Document11 pagesProclamation of Independence, 17 April 1971: East West University GEN 226 / Lecture 17Md SafiNo ratings yet

- New 1231231234Document250 pagesNew 1231231234Brazy BomptonNo ratings yet

- Verbal Abuse II PDFDocument2 pagesVerbal Abuse II PDFiuliamaria94100% (1)

- Suffolk County Patrolmen's Benevolent Association, Inc., P.O. Robert Pfeiffer, P.O. Robert Ryan, P.O. Attila Nemes, P.O. Ray Campo, Det. Dennis Romano, P.O. Frank Delgaudio, P.O. Jim Meehan, P.O. Robert Pflaum, P.O. Bill Bennett, P.O. Rodger Larocca, P.O. Howard McAulby P.O. Ed Fitzgerald, P.O. Sam Dejusus, P.O. Keith Fontana, P.O. Louis Bruno, P.O. Bruce Klimecki, P.O. Philip Buzzanca, P.O. Robert Haisman, P.O. Gerry Gozaloff, P.O. Arthur Dowling, Det. Anthony Bivona, P.O. Donald Berzolla, P.O. Frank Giuliano, P.O. John Niedzielski, P.O. Dennis Green, Det. John Christie, and Det. Frank Pacifico v. County of Suffolk James O. Patterson, Individually and in His Official Capacity Martin Ashare, Individually and in His Official Capacity John P. Finnerty, Jr., Individually and in His Official Capacity Christopher Termini, Individually and in His Official Capacity, 751 F.2d 550, 2d Cir. (1985)Document3 pagesSuffolk County Patrolmen's Benevolent Association, Inc., P.O. Robert Pfeiffer, P.O. Robert Ryan, P.O. Attila Nemes, P.O. Ray Campo, Det. Dennis Romano, P.O. Frank Delgaudio, P.O. Jim Meehan, P.O. Robert Pflaum, P.O. Bill Bennett, P.O. Rodger Larocca, P.O. Howard McAulby P.O. Ed Fitzgerald, P.O. Sam Dejusus, P.O. Keith Fontana, P.O. Louis Bruno, P.O. Bruce Klimecki, P.O. Philip Buzzanca, P.O. Robert Haisman, P.O. Gerry Gozaloff, P.O. Arthur Dowling, Det. Anthony Bivona, P.O. Donald Berzolla, P.O. Frank Giuliano, P.O. John Niedzielski, P.O. Dennis Green, Det. John Christie, and Det. Frank Pacifico v. County of Suffolk James O. Patterson, Individually and in His Official Capacity Martin Ashare, Individually and in His Official Capacity John P. Finnerty, Jr., Individually and in His Official Capacity Christopher Termini, Individually and in His Official Capacity, 751 F.2d 550, 2d Cir. (1985)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Lesson 4 PDFDocument21 pagesLesson 4 PDFShenn Silva RockwellNo ratings yet

- Journal Article PhoebeDocument20 pagesJournal Article PhoebeAnonymous 4yc7LNWCB9100% (1)

- One Deped One Pampanga: Name of PupilDocument2 pagesOne Deped One Pampanga: Name of PupilIRENE S.TUPASNo ratings yet

- Iran's Expanding Militia Army in IraqDocument38 pagesIran's Expanding Militia Army in IraqUbunter.UbuntuNo ratings yet

- Stuart Hall: "Culture Is Always A Translation"Document5 pagesStuart Hall: "Culture Is Always A Translation"MelissaChouglaJoseph100% (1)

- Modern History - Power and Authority in The Modern WorldDocument22 pagesModern History - Power and Authority in The Modern WorldDarksoulja1 GreatestNo ratings yet

- Constitutional History of PakistanDocument10 pagesConstitutional History of PakistanZulfiqar AhmedNo ratings yet

- 1.04 Adlawan V Joaquino DigestDocument1 page1.04 Adlawan V Joaquino DigestKate GaroNo ratings yet

- Euro-Orientalism and the Making of Eastern EuropeDocument38 pagesEuro-Orientalism and the Making of Eastern EuropeBaruch SpinozaNo ratings yet

- Quezon City and Its StoryDocument1 pageQuezon City and Its StoryAnjaneth CabutinNo ratings yet

- Witch Hunting of The Adivasi Women in JharkhandDocument7 pagesWitch Hunting of The Adivasi Women in JharkhandIshitta RuchiNo ratings yet

- Test Bank For Employment Law For Business 10th Edition Dawn Bennett Alexander Laura HartmanDocument50 pagesTest Bank For Employment Law For Business 10th Edition Dawn Bennett Alexander Laura HartmanandrewgonzalesqngxwbatyrNo ratings yet

- Madhya Pradesh High Court Order On Munawar Faruqui's Bail PleaDocument10 pagesMadhya Pradesh High Court Order On Munawar Faruqui's Bail PleaThe WireNo ratings yet

- Malaysian undergrads' views on bilingual educationDocument2 pagesMalaysian undergrads' views on bilingual educationseketulkiddoNo ratings yet

- Case Studies - The Case of The Malicious ManagerDocument6 pagesCase Studies - The Case of The Malicious ManagerKarl Jason Dolar Comin50% (8)

- Week 5 Intercultural CommunicationDocument32 pagesWeek 5 Intercultural CommunicationPopescu VioricaNo ratings yet

- Silverio v. Republic DigestDocument2 pagesSilverio v. Republic DigestGabriel FranciscoNo ratings yet

- Consti 1 CasesDocument9 pagesConsti 1 CasesEm AlayzaNo ratings yet