Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Learning vs. Doing

Uploaded by

mroslifrimCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Learning vs. Doing

Uploaded by

mroslifrimCopyright:

Available Formats

17/08/2012

Learning vs. Doing (or why that Ph.D. took 10 years) | Our 2 SNPs

Learning vs. Doing (or why that Ph.D. took 10 years)

Posted on August 15, 2012 by Christophe Lambert

What prevents scientists from being more productive and if we knew, could we do

anything about it?

Id like to look at an often overlooked, but huge productivity inhibitor bad multitasking.

Many people put excellent multitasker on their resume as a badge of honor. We laud the

efficiency of a good multitasker they are rarely idle someone that busy must be

getting a lot of work done, right?

What Multitasking Looks Like, Visually

Let us visually consider the impact of multitasking on task completion, and see why Im tempted to put excellent

multitasker resumes into the round file.

In the figure below, we have 3 tasks which each take the same amount of time to complete say 15 days. If we

perform each task sequentially without interruption, then tasks A, B, and C will be completed at day 15, 30, and

45 respectively.

Consider then, a more typical multitasking workflow where we alternate between tasks A, B, and C doing, say 5

days of work on each before switching to the next one, alternating until all tasks are finished. As shown below,

task A is completed by day 35, task B by day 40, and task C by day 45.

For most projects it is fair to say that the benefits are not realized until the project is complete. That is, the

money, time, and resources invested in project execution is not bringing a return until project completion. In the

first scenario, the benefits of project A could be realized after 15 days, and project B after 30 days. In the

multitasking scenario, the benefits of project A and B were not realized until day 35 and beyond more than

double the time of serially tackling the tasks one by one.

It gets worse. Context switching between tasks causes loss of flow that state of uninterrupted concentration

where we work at our best. And lets also acknowledge that if 10 days elapses before returning our attention to a

task, that we are going to have to spend additional time recalling context and getting back up to speed from

where we left off.

Lets conservatively add a day of switching costs between each task. With this assumption, task A would be

done by day 41, task B by day 47, and task C by day 53. We have almost tripled the time to see the results from

task A!

Instead of 3 tasks, consider the

blog.goldenhelix.com/?p=1367

1/5

17/08/2012

Learning vs. Doing (or why that Ph.D. took 10 years) | Our 2 SNPs

dozens of things most of us have going concurrently in our lives it is no wonder we never finish many of the

things we start.

Why Researchers Are the Worst of Multitaskers

I contend that generally, researchers are the worst of multitaskers it would be unusual to find one with less

than 20 different irons in the fire. Like a butterfly or honeybee hopping from flower to flower, a researcher

delights in nothing more than starting something new, getting distracted by something else novel, and hopping

from one thing to the next. The productivity implications are devastating. Why then do we do this?

A very important need is satisfied by being a honeybee: cross-pollination of ideas. Researchers are driven by

curiosity, by learning. Seeking diversity and synergizing ideas across multiple domains is a well-used learning

strategy.

But this strategy puts a researcher into the following dilemma:

An evaporating cloud diagram describing the learn versus do conflict for

researchers.

In order to be a successful researcher, one must both learn and get a lot done, which for those in our field

usually means completing research projects and publishing results. To learn and satisfy the natural drive for

curiosity (B), a researcher naturally jumps from area to area in their intellectual exploration (multitasking) (D). On

the other hand, if a researcher wants to publish and get stuff done (C), they should seek to focus on few projects

and see them through to completion (minimize multitasking) (D).

So how does any doing get done? Professors have a great labor saving device, employed at least since the

time of Isaac Newton: the graduate student! Yet other than for the ber-funded, ideas for new projects can be

generated faster than any army of graduate students could hope to keep pace with. Can you say 10-year

Ph.D.? The multitasking gets transferred to them!

Multitasking and the Reiss Profile

Back to my opening question if we knew better would we do better? I have known about the killer implications

of bad multitasking for over 7 years, yet I have only begun to mend my ways. The curiosity urge is too strong.

I think the core reason we multitask boils down to one simple cause: at this moment I would rather do

something else. What then determines what we would rather do?

A psychology professor, Steven Reiss, did a factor analysis on hundreds of things people said they value and

came up with 16 reasonably orthogonal values that characterize goal-seeking behavior in humans (interestingly

their basis can be traced to evolutionary survival needs). He developed a test, the Reiss Profile, to determine the

extent the 16 values are higher or lower than average for a given person. The values are: acceptance,

romance/beauty, curiosity, eating, honor, family, idealism, independence, order, physical exercise, power,

saving, social contact, status, tranquility, and vengeance. Each of us have lower or higher levels of drive towards

blog.goldenhelix.com/?p=1367

2/5

17/08/2012

Learning vs. Doing (or why that Ph.D. took 10 years) | Our 2 SNPs

performing actions that fulfill the above needs. Further, our most dominant behaviors are

driven by attraction to doing more of what we value highly and aversion to doing more of

what we value minimally. I hypothesize that high curiosity is overrepresented among

researchers, and high order is overrepresented among administrators. This might

explain why there is often a fight between these two camps over filling out reports!

We have many values that drive our behavior. To the extent we can do work that fulfills

most or all of our needs simultaneously, we dont need to multitask. When this is not the

case, we multitask to fill up our value tanks as time elapses when we havent had

enough of something else we value, or to stop filling a tank of a value that is satiated.

The real challenge is to construct a career that maximizes action along the lines of what we value, and minimizes

or delegates actions we dont value to those who do value those activities. There are also ways of reframing so

that unvalued activities are seen in light of how they contribute at a higher level context to something we value

reducing the misery and stress of that stuff we just have to do but dont really want to.

Learning vs. Doing

So as researchers, would we rather be learning than doing? But wait a minute is that really possible?

The generation of knowledge occurs in a continuous cycle of forming theories or models that describe the way

the world works, and then testing those models in the arena of action, learning better ones through trial and error.

That is the essence of the scientific method discussed at length in a recent webinar of mine. It is easy to build

castles in the clouds ideas disconnected from reality and action if we only think and rarely do.

Taking the learn/do conflict to an international scale, consider the

positioning of America as a knowledge economy. While we may

differ on what we mean by this term, lurking in there is an idea

something like America will do the thinking and other economies will

do the doing. That is, we will specialize in the superior high-value

knowledge work, and offshore workers will roll up their sleeves and

do the dirty work of manual labor.

There is a key fallacy in positioning a nation exclusively as a knowledge economy. If you disconnect the learning

from the doing, you slow down both of them. Learning occurs fastest with the instant feedback of doing.

Therefore, the economies that roll up their sleeves, make things, and bounce models off of reality will learn an

order of magnitude faster than those who do so through others across an ocean and 12 time zones. The doers

blog.goldenhelix.com/?p=1367

3/5

17/08/2012

Learning vs. Doing (or why that Ph.D. took 10 years) | Our 2 SNPs

quickly catch up and become higher value situated knowledge

economies.

Consider that in science, if researchers stop short of trying to falsify

their hypotheses in the laboratory of reality, they dont really learn.

This was discussed at length in my post: Dammit Jim, Im a doctor,

not a bioinformatician! When you abstract a real-world problem into a

model, you reduce the degrees of freedom and then it is more

manageable. According to Ashbys law of requisite variety, if you want

to control a system, the controller has to have more degrees of

freedom than the controlee. Our models have low degrees of

freedom, and messy reality has high degrees of freedom. So it

actually takes more degrees of freedom, more mental horsepower to

translate theory into the world of action. This is the learning loop of

modeling reality and testing against reality.

So to sum up: there is no such thing as learning without doing it is a

false dichotomy!

And Me?

Obeying the maxim Physician heal thyself, Im working on the multitasking thing along with 20 other projects.

When I make some progress, Ill let you know. Fundamentally I think the challenge is making the paradigm shift

from: productivity=activity to productivity=task completion, and figuring out how to do what we love. And I

believe that there is a way to break the assumption that the only way to learn is through unfettered diversity

exploration. There is a 60+ year old body of knowledge, TRIZ, that breaks this assumption, but requires us to

bypass our normal (cherished) modes of thinking. That too represents a paradigm shift. So at the end of the day,

the real challenge is how to make paradigm shifts and not have to wait a generation for them to happen.

Nevertheless, there are simple things we can do short of making a paradigm shift that can give us a significant

productivity boost. Besides our butterfly mind, some of the biggest additional contributors to bad multitasking are

external factors that interrupt our concentrated work. It is pretty bad when we have institutionalized a culture of

automated interruption though email pop-ups with sound reminders on our computers and smartphones. I shut

these off years ago, and it has made a huge difference in creating conditions for uninterrupted flow.

Too much praise has been sung for the open door policy and management by walking around (interrupting)

and not enough attention to setting blocks of time aside that co-workers know are uninterruptible short of a real

emergency and this needs to include both physical and virtual (e.g. text message) interruptions. If the

productivity boost is not motivation enough, Ive discovered after weaning myself from the addiction to

continuous interruption, that the real payoff for uninterrupted flow is more happiness.

And who doesnt want more of that?

About Christophe Lambert

Dr. Christophe Lambert is the Chairman and CEO of Golden Helix, Inc., a bioinformatics software and services company he founded in Bozeman,

MT, USA in 1998. Dr. Lambert graduated with his Bachelors in Computer Science from Montana State University in 1992 and received his Ph.D. in

Computer Science from Duke University in 1997. He has performed interdisciplinary research in the life sciences for over twenty years.

View all posts by Christophe Lambert

This entry was posted in Big picture. Bookmark the permalink.

blog.goldenhelix.com/?p=1367

4/5

17/08/2012

Learning vs. Doing (or why that Ph.D. took 10 years) | Our 2 SNPs

2011 Golden Helix, Inc. All Rights Reserved

blog.goldenhelix.com/?p=1367

Privacy Policy | Contact Us

5/5

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Proceedings of Biological Control of WeedsDocument766 pagesProceedings of Biological Control of WeedsmroslifrimNo ratings yet

- Molecules 16 04884Document13 pagesMolecules 16 04884vijaykavatalkarNo ratings yet

- Cellulase Enzyme Production by Streptomyces SP Using Fruit Waste As SubstrateDocument5 pagesCellulase Enzyme Production by Streptomyces SP Using Fruit Waste As SubstrateHamka NurkayaNo ratings yet

- D 912 F 50 Af 92 D 6 A 4 D 68Document13 pagesD 912 F 50 Af 92 D 6 A 4 D 68Ben GeorgeNo ratings yet

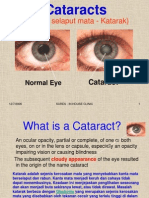

- Cataract and Eye Care DCaDocument26 pagesCataract and Eye Care DCaSamuil SumpalNo ratings yet

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Rabindranath TagoreDocument13 pagesRabindranath TagoreVinay EkNo ratings yet

- Structural Elements For Typical BridgesDocument3 pagesStructural Elements For Typical BridgesJoe A. CagasNo ratings yet

- Destination Visalia, CA - 2011 / 2012 1Document44 pagesDestination Visalia, CA - 2011 / 2012 1DowntownVisaliaNo ratings yet

- Guideline Reading Diagnosis and Management of Pericardial DiseaseDocument87 pagesGuideline Reading Diagnosis and Management of Pericardial DiseaseMirza AlfiansyahNo ratings yet

- Fundamentals of Parenteral NutritionDocument4 pagesFundamentals of Parenteral NutritionankammaraoNo ratings yet

- Johnson Claims Against Eaton AsphaltDocument39 pagesJohnson Claims Against Eaton AsphaltCincinnatiEnquirerNo ratings yet

- Hampers 2023 - Updted Back Cover - FADocument20 pagesHampers 2023 - Updted Back Cover - FAHaris HaryadiNo ratings yet

- Unit - 5 - Trial BalanceDocument7 pagesUnit - 5 - Trial BalanceHANY SALEMNo ratings yet

- Hamlet Greek TragedyDocument21 pagesHamlet Greek TragedyJorge CanoNo ratings yet

- IdentifyDocument40 pagesIdentifyLeonard Kenshin LianzaNo ratings yet

- A Deep Dive Into 3D-NAND Silicon Linkage To Storage System Performance & ReliabilityDocument15 pagesA Deep Dive Into 3D-NAND Silicon Linkage To Storage System Performance & ReliabilityHeekwan SonNo ratings yet

- Deep Learning The Indus Script (Satish Palaniappan & Ronojoy Adhikari, 2017)Document19 pagesDeep Learning The Indus Script (Satish Palaniappan & Ronojoy Adhikari, 2017)Srini KalyanaramanNo ratings yet

- A Natural Disaster Story: World Scout Environment BadgeDocument4 pagesA Natural Disaster Story: World Scout Environment BadgeMurali Krishna TNo ratings yet

- Chapter Three: The Topography of Ethiopia and The HornDocument4 pagesChapter Three: The Topography of Ethiopia and The Horneyob astatke100% (1)

- Suarez-Eden v. Dickson Et Al - Document No. 3Document9 pagesSuarez-Eden v. Dickson Et Al - Document No. 3Justia.comNo ratings yet

- Resume 5Document5 pagesResume 5KL LakshmiNo ratings yet

- Lesson 4 Prepare and Interpret Technical Drawing: Alphabet of LinesDocument26 pagesLesson 4 Prepare and Interpret Technical Drawing: Alphabet of LinesREYNALDO BAJADONo ratings yet

- METCON 6 Quickstart Action PlanDocument9 pagesMETCON 6 Quickstart Action PlanVictorNo ratings yet

- People vs. Samson, September 2, 2015Document5 pagesPeople vs. Samson, September 2, 2015Alpha Grace JugalNo ratings yet

- Q400 PropellerDocument10 pagesQ400 PropellerMoshiurRahman100% (1)

- Earth and Life Science: Quarter 2 - Module 13 The Process of EvolutionDocument27 pagesEarth and Life Science: Quarter 2 - Module 13 The Process of EvolutionElvin Sajulla BulalongNo ratings yet

- Assessment of The Role of Radio in The Promotion of Community Health in Ogui Urban Area, EnuguDocument21 pagesAssessment of The Role of Radio in The Promotion of Community Health in Ogui Urban Area, EnuguPst W C PetersNo ratings yet

- State Bank of India: Re Cruitme NT of Clerical StaffDocument3 pagesState Bank of India: Re Cruitme NT of Clerical StaffthulasiramaswamyNo ratings yet

- Standard Operating Procedures in Drafting July1Document21 pagesStandard Operating Procedures in Drafting July1Edel VilladolidNo ratings yet

- Police Law EnforcementDocument4 pagesPolice Law EnforcementSevilla JoenardNo ratings yet

- Tesla Roadster (A) 2014Document25 pagesTesla Roadster (A) 2014yamacNo ratings yet

- Review of DMOS in CNHSDocument54 pagesReview of DMOS in CNHSrhowee onaganNo ratings yet

- Critical Methodology Analysis: 360' Degree Feedback: Its Role in Employee DevelopmentDocument3 pagesCritical Methodology Analysis: 360' Degree Feedback: Its Role in Employee DevelopmentJatin KaushikNo ratings yet

- Npcih IDocument2 pagesNpcih IRoYaL RaJpOoTNo ratings yet