Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Grinding Wheels of Justice

Grinding Wheels of Justice

Uploaded by

Priyatam BolisettyCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Grinding Wheels of Justice

Grinding Wheels of Justice

Uploaded by

Priyatam BolisettyCopyright:

Available Formats

EDITORIALS

Grinding Wheels of Justice

The judgments in the Katara murder and Uphaar fire cases show that justice delayed is justice denied.

hirteen years after 25-year-old Nitish Katara was killed,

the Supreme Court recently upheld the conviction of

his killers. Judicial delays, unfortunately, are only too

predictable in India. Just days after the Katara ruling, the apex

court gave its final ruling in the Uphaar cinema hall fire case

that had killed 59 people (23 of whom were minors) in New

Delhi, 18 years after the event.

The responses to the two judgments, however, were vastly

different. In both cases, the mothers and parents of the victims

who were predominantly middle class had waged a long and

tedious legal battle against rich and influential opponents. But

while in the Katara murder case, the Court said that it was a

classic example of how the rich and powerful people try to influence the justice delivery system, the other ruling was seen as

punishing the theatre owners, who are real estate tycoons, too

little and too late. They were asked to deposit Rs 60 crore with

the Delhi government to be used to build a trauma centre. The

two Ansal brothers (one had earlier spent five months in jail,

and the other four months) were free.

In their different ways, the two cases and their rulings raise

a number of issues pertaining to police investigation, witness

protection or the lack of it, the role of the mainstream and social

media and, of course, the perennial one of judicial delays forcing

litigants to face an intolerable strain on their emotional and

financial resources.

The son (Vikas) and nephew (Vishal) of ex-Rajya Sabha

member D P Yadav were convicted in 2008 for killing their

sister Bhartis classmate and friend, Nitish Katara, in 2002.

Yadav senior is often described as a don of Ghaziabad District

and had a reputation of being a kingmaker in politics of

Uttar Pradesh. Incidentally, Vikas Yadav was one of the accused

in the Jessica Lal murder case too. Witnesses, including Nitish

Kataras friends, turned hostile during the trial to the extent

that the Supreme Court was moved to comment upon it, the

public prosecutor was changed, allegedly to suit the powerful

family of the accused, and the two accused made 85 medical

outings in less than two years even though they were serving

a life term.

The murder was acknowledged to be an honour killing by

the Court and more significantly showed the stranglehold of

patriarchy even over a well-educated young woman. The Yadav

brothers were quoted as saying that her close friendship with

Nitish was harming their family reputation. Not only did she

end up denying the relationship with Katara when her brothers

were in the dock but was also sent off abroad to study even

as every effort was made to ensure that she did not return to

depose in court (she did in the end).

Neelam Kataras saga with the judicial system called for

extraordinary courage to withstand the immense pressures

exerted by her opponentsa fact acknowledged by the Delhi

High Court in its 2008 ruling. She has said that, apart from

becoming the single all-consuming centre of her life, it also

drained her financially.

In the Uphaar fire case, the litigants formed the Association

of the Victims of Uphaar Tragedy (AVUT) to fight opponents

who had immense financial staying power. After the recent

court ruling they told the media that they felt cheated not

only by the judiciary but also by a government that had refused

to pull up those who were responsible for turning a blind eye

to the deliberate disdain for safety rules by the theatre

owners, the staff of the Delhi Electric Supply Undertaking and

others involved.

In both the Katara murder and the Uphaar fire tragedy cases,

the mainstream media largely stood on the side of the victims.

The experiences of middle-class mothers fighting the moneyed

and well-connected on behalf of their dead children caught the

medias attention. This was all for the good of course but it also

raised questions whether this kind of selective prominence to

some cases by the media was due in large part to the obvious

class location of its readers and viewers (as well as the victims),

or was it truly an exercise in media activism in a democratic

society. The earlier social media campaigns in the case of the

Jessica Lal and Priyadarshini Mattoo murder cases and the

resultant convictions are part of this same trend. Alas, these

issues, including that of how the media chooses the case it will

espouse, have not really been debated fully.

The Katara murder case and the Uphaar cinema fire case are

both testimonies to the indomitable spirit of the litigants who

fought long and hard for justice to the victims. But they also

show the lack of a strong witness protection system (in the Katara case the apex court told the accused that witnesses resiled

because you made them resile) and of professional police investigations that help get convictions for serious crimes. More

significantly, they show the ability of the powerful to ensure

that legal proceedings drag on interminably to grind down the

morale and resources of those taking them on. Whether the

judgment is welcomed or not, even these high-profile cases

show that justice delayed is justice denied.

AUGUST 22, 2015

vol l no 34

EPW

Economic & Political Weekly

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5810)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1092)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (843)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (346)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Vol 111 17th January 2016 TO 23rd January 2016Document57 pagesVol 111 17th January 2016 TO 23rd January 2016Priyatam BolisettyNo ratings yet

- FL Test 2 Self StudyDocument42 pagesFL Test 2 Self StudyPriyatam BolisettyNo ratings yet

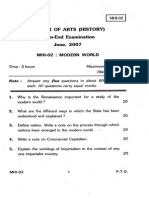

- World History June 2007Document4 pagesWorld History June 2007Priyatam BolisettyNo ratings yet

- World History Dec 2008Document8 pagesWorld History Dec 2008Priyatam BolisettyNo ratings yet

- ED L 36 050915 Problem Animals' Are Not The Real ProblemDocument1 pageED L 36 050915 Problem Animals' Are Not The Real ProblemPriyatam BolisettyNo ratings yet

- Indian Urbanism and The Terrain of The LawDocument10 pagesIndian Urbanism and The Terrain of The LawPriyatam BolisettyNo ratings yet

- Making of The ConstitutionDocument12 pagesMaking of The ConstitutionPriyatam BolisettyNo ratings yet

- Business Law: HMM 201 Unit - 1Document40 pagesBusiness Law: HMM 201 Unit - 1Kunal JindalNo ratings yet

- Malta - Maritime ClusterDocument20 pagesMalta - Maritime Clustergrzug111No ratings yet

- Pilipino Telephone Corp Vs Radiomarine NetworkDocument11 pagesPilipino Telephone Corp Vs Radiomarine NetworkCatherine MerillenoNo ratings yet

- RULE 13 SEC 7 Land Bank Vs Heirs of AlsuaDocument2 pagesRULE 13 SEC 7 Land Bank Vs Heirs of AlsuaRedSharp706No ratings yet

- Director of Prisons V Ang Cho KioDocument3 pagesDirector of Prisons V Ang Cho KioTon RiveraNo ratings yet

- Plaintiffs' Motion For Summary JudgmentDocument56 pagesPlaintiffs' Motion For Summary JudgmentBasseemNo ratings yet

- Bona Vs BrionesDocument2 pagesBona Vs BrionesCMG100% (1)

- Gainor v. Sidley, Austin, Brow - Document No. 13Document2 pagesGainor v. Sidley, Austin, Brow - Document No. 13Justia.comNo ratings yet

- Form of UndertakingDocument5 pagesForm of UndertakingSujata MansukhaniNo ratings yet

- TRACKING BAPS 2021 - ActualDocument70 pagesTRACKING BAPS 2021 - ActualAbraham GamerosNo ratings yet

- Acp - Dissolution and LiquidationDocument2 pagesAcp - Dissolution and LiquidationMoon100% (1)

- Capili Vs People (2013)Document1 pageCapili Vs People (2013)Carlota Nicolas VillaromanNo ratings yet

- United States v. Phillip Potter, 4th Cir. (2014)Document5 pagesUnited States v. Phillip Potter, 4th Cir. (2014)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Courtesy Costs Nothing But Buys EverythingDocument3 pagesCourtesy Costs Nothing But Buys EverythingImani AinaNo ratings yet

- Substantive Due Process of LawDocument66 pagesSubstantive Due Process of LawJeff WinchesterNo ratings yet

- The University of Oxford Continuing Education Open Access Terms and ConditionsDocument4 pagesThe University of Oxford Continuing Education Open Access Terms and ConditionsrguedezNo ratings yet

- Macalino and Elcox CreditDocument5 pagesMacalino and Elcox CreditElla B.No ratings yet

- Administrative Discretion and Judicial ControlDocument17 pagesAdministrative Discretion and Judicial Controlpintu ramNo ratings yet

- Guidelines DO16Document77 pagesGuidelines DO16Marlo ChicaNo ratings yet

- Marketing Communication Plan For AmulDocument11 pagesMarketing Communication Plan For AmulWizard KarmaNo ratings yet

- Law Student Rule: Problem Areas in Legal EthicsDocument25 pagesLaw Student Rule: Problem Areas in Legal EthicscardeguzmanNo ratings yet

- Crime Seen:: Racial Terror and The Technologies of Black Life and DeathDocument1 pageCrime Seen:: Racial Terror and The Technologies of Black Life and DeathMargarita Barcena LujambioNo ratings yet

- Legal Education Board: Hon. Emerson B. Aquende Chairperson IBP RepresentativeDocument1 pageLegal Education Board: Hon. Emerson B. Aquende Chairperson IBP RepresentativeDiana PobladorNo ratings yet

- Republic of The Philippines vs. Manalo FactsDocument2 pagesRepublic of The Philippines vs. Manalo Factsjoel ayonNo ratings yet

- Casus Omissus Pro Omisso Habendus Est - A Person, Object, or Thing Omitted FromDocument3 pagesCasus Omissus Pro Omisso Habendus Est - A Person, Object, or Thing Omitted FromCP LugoNo ratings yet

- Chapter 3 - Effect of The Contract When The Thing Sold Has Been Lost Distinction of Different PrinciplesDocument35 pagesChapter 3 - Effect of The Contract When The Thing Sold Has Been Lost Distinction of Different Principlesrunish venganzaNo ratings yet

- THE MEANING AND PURPOSE OF HUMAN SEXUALITY by Samuel B. BataraDocument3 pagesTHE MEANING AND PURPOSE OF HUMAN SEXUALITY by Samuel B. BataraSamu BataNo ratings yet

- EXTRAJUDICIAL Settlement of Estate APRONIO CORONADODocument3 pagesEXTRAJUDICIAL Settlement of Estate APRONIO CORONADOFiona FedericoNo ratings yet

- Answer and Affirmative Defenses in Figueroa v. SzymoniakDocument13 pagesAnswer and Affirmative Defenses in Figueroa v. SzymoniakMartin AndelmanNo ratings yet

- Georamur Universal Affidavit of Fact With Command FOR ACCESS TO ACCOUNTDocument3 pagesGeoramur Universal Affidavit of Fact With Command FOR ACCESS TO ACCOUNTGeoramur100% (3)